Splintered Realities

The late 20th century witnessed the triumph of a mainstream news media, interpreting the world on our behalf, rendering it intelligible. It was this media ecology that shaped perceptions of warfare. This was a monopolistic vision of the world, highly attuned to the sensitivities of news audiences, their capacity to take offence, and their finding comfort in the censored and the sanitized. War was something carefully controlled and rendered digestible by media for the masses consuming in a shared consensual reality. That reality has shattered.

Today, War Has Been Taken Over By the Self

The war against Ukraine is unique in its unfolding through a prism of personalized realities, made and remade for individuals, in what we call the “war feed.” The war feed is the principal media means through which war today is perceived, participated in, fought over, legitimized, and how it will be remembered and forgotten in the future. Digital technologies have liberated production and distribution from the mainstream, empowering every individual and giving voice to an astonishing array of ideas, opinions, and experiences (). But it is this same liberation to produce, comment on and share digital media content that is transforming the nature and experience of modern warfare.

The war feed is a new spectrum of warfare located in and through messaging apps and platforms. It is how individual locating and targeting, surveillance, psychological operations, trolling, and disinformation, are all enabled through digital networks, streams, and archives. These aspects of war thrive precisely because of the rapid growth in the recording and sharing of all those on the battlefield, and their clicking, swiping, linking, liking, emoting, sharing stories, messages, images, memes, and videos.

These forms of war have never been so plentiful, pouring today from the battlefield from militaries, soldiers, journalists, states, NGOs, citizens, artists—weaponizing the smartphone and satellites—and which overwhelm in their sheer scale, seemingly beyond human apprehension. But the war feed is also defined by a frenzy of participation, a stream of commentary, emojiing, linking, chatting, liking, and so on that creates a new complex layer of mediation and interpretation, which continuously (re)personalizes and (re)mixes media content of all kinds.

Multimedia smartphones, messaging apps and platforms have enabled the individual to become the principal documenter of and the principal subscriber to war. There are an incredible variety of ways in which information and images about this war are being captured, shared, dissected, and commented upon. Individuals, civilians, victims, aid workers, soldiers, militaries, governments, political leaders, journalists, news and satellites organizations, NGOs, open-source organizations, all recording and uploading their experience and vision of events minute by minute, second by second. This creates a new multidirectionality of the media content of war, highly personalized and individualized, yet also massified, in terms of the billions of participants plugged into the “new war ecology” ().

This new participative environment of war also implodes the distinctions between soldier, civilian, and informational warrior, fundamentally disrupting the relationship between warfare and society, in the blurring of these formerly distinct roles and implicating so many more in what war is and how it is fought and understood.

The Russian war launched against Ukraine in 2022 then, as found in the war feed, certainly gives the impression of being highly accessible. Never has there been so much information and disinformation available about war with such immediacy, recorded via smartphone and satellites, shared via chat and messaging apps and an array of social media platforms. The wreckage of the everyday of villages, homes, hospitals, and schools, the journeys of the displaced millions, the targeting by and of drones and tanks, the constant strategizing of the Twitterati, the resilience and bravery of Ukrainian civilians and soldiers, the living conditions of Russian conscripts, there is little that escapes the digital tracking and streaming of this war.

But it is wrong to call this war in any way transparent. “Open source” has always been a misnomer. Rather, this is more like crowd-sourced war, that is a war in which the claims, opinions, and outrage of anyone who can post, link, like, or share on social media, splinter multiple realities of experience. But even this notion of “crowd” is misleading in not capturing how individuals create a separate reality, which are so different to the digital realities of others. It is the opposite of the globalized vision so defining of the satellite television age of war of the late 20th century.

Instead, the splintering of the war feed defines a paradox, of the war in Ukraine being the least and yet most sanitized war in history. Never have so many images and videos of the suffering, injured, captured, mutilated and the dead, civilians and soldiers, been so immediately and easily available from a war zone. These are used as a digital instrument of psychological warfare. For example, a stream of graphic posts on some channels on the messaging platform Telegram are accompanied with comments and emojis, laughing, celebrating capture, injury, and death. This is part of the new participative layering of mediation and interpretation in the war feed.

Yet, these splinters of horror do not dent the highly sanitized vision of war in mainstream news and on many social media platforms that edit and moderate a version of war that is presumed to be much more acceptable or tolerable for their viewers and users.

Perhaps this is only an intensifying of a long-standing relationship between a mainstream vision of the world (including that found on many social media platforms) and what is available around the edges (). For most, the worst of the horror of war is pushed to the corner of the eye, rarely brought into focus.

This also highlights the void between a debate over the responsibility and control of companies over their social media platforms in terms of the content that is visible and that which is not, and the free-for-all that is Telegram. There seems little point in raging against ineffectual moderation policies and mechanisms, the algorithmic production or exacerbation of hatred, or Big Tech’s resistance to regulation and oversight, whilst the world burns on Telegram.

There is nothing nuanced, tempered, or obscured in the stream of the mutilated and the dead on some Telegram channels—this is (psychological) war in plain sight. Yet this is nonetheless, for most, buried beneath the layers and the splinters of the war feed. And that is why it makes no sense to call this a “social media” war, for there is no such thing as a unified “social media” around which this war could be coherently communicated and contained.

In this paper then, we set out a new model of the war feed as the defining means through which today war is perceived, experienced, propagandized, remembered, and forgotten, by individuals all now participating.

Despite the apparently amazing availability of images, video, messages, information, and news from Ukraine, and the sense of agency of all those participating, the most documented war in history has so easily become the most obscured. This is the paradox of the war feed: the frenzy of participation amidst a digital tsunami of media content, does not translate into a real revolution of seeing war. Rather, a post-scarcity hyperconnectivity of digital media form, content, and archive (, ) implode the 20th century’s mainstream news regime of ordered reassurance and trajectories of certainty premised upon “usable” pasts (how lessons are learned). What are we left with then in this new war ecology?

Telegram as a Media Ecology

Media ecology has long been seen as the shifting nature of the media environment and how its communicational forms “affect human perception, understanding, feeling, and value; and how our interaction with media facilitates or impedes our chances of survival.” Associated with influential early media theorists of and and developed by , the word “ecology” was coined by the scientist Ernst Haeckel in 1869 to mean roughly the study of the relations between organisms and their environment. Since then, the term has evolved and been refined, for instance seeing ecology as: “the scientific study of the distribution and abundance of organisms and the interactions that determine distribution and abundance” (, p. xi). However, argue that the importance of “environment” is that the “interactions” are precisely with those factors and phenomena outside the organism.

“Media ecology” is a term that has also been used to highlight the impact of our interactions with media, with others through media, and also increasingly the dynamic processes that occur between media. Many associate the term itself with the late 1950s and 1960s work of Marshall McLuhan, although it has a much longer history. “Media ecology” is often traced to its naming by Neil Postman in a 1970 edited volume High School 1980 that attempted to imagine the future shape of American secondary education. Postman championed the teaching of media ecology as an alternative to English in the future high school, namely as “the study of media as environments,” but also the “study [of] the interaction between people and their communications technology” (, p. 161). In our account it is the relative collapse of these two domains—the media environment, and interactions between us and our technologies—that shapes a “new media ecology” today (cf. ; a). In other words, it is defined by relations of hyperconnectivity between media and humans, and increasingly media with other media.

In the context of war, argue that the 2020s are becoming marked by a “new war ecology,” that warfare is something that encompasses multiple media ecologies that are in various stages of development, depending on levels of connectivity to the internet, participation on social media, use of broadcast media, and press freedoms. The 2022 Russian war against Ukraine is shaped by militaries, states, citizens, NGOs all adapting and exploiting pre-existing media ecologies, to highlight their own experiences, to push their own views and agendas, along a wide spectrum of intent, coordination, and resources.

One such unique media ecology shaping the Russian war against Ukraine is the Telegram messenger app. Telegram is a messenger which allows an author to create a public newsfeed with videos, audios, and texts. In contrast to other means of Internet communication, Telegram is not a social network, since every aspect of interaction with the audience is controlled by the channel owner. For example, it is technically possible to run a Telegram channel with a million subscribers that has no comment section or “like” button, although many open their posts to a frenzy of comments, shares, and emojis.

Telegram is a different kind of front in this war, in that it is a media ecology that is not subject to the regulatory and moderating mechanisms and controls (and debates) associated with many social media platforms. At least in the early stages of this war, there was political pressure applied to mostly Silicon Valley-owned or located platforms to inhibit the reach of Russian propaganda and disinformation. Yet the Russian-owned Telegram is probably the most accessible battlespace in this war, as its channels are not obfuscated by algorithms and are also downloadable and achievable in their entirety.

But this is war in plain sight that is only really seen through the splinters of its channels’ subscribers. This is fractal war—where you choose to subscribe to your own tailored version of warfare in your feed—or avoid it altogether. This makes it the most personalized war in history. And Telegram is at the heart of the digital battlefield between Ukraine and Russia, used by more than 70% of Ukrainians and 25% of Russians.

What Telegram creates in times of war is an army of bloggers who exploit the most archaic desires of humans and an army of users who wallow in their manipulation. In Telegram it is my choice as a consumer to create my newsfeed; if I do not put a specific effort into creating such a collection of different sources that would contradict and complement each other, what happens most likely is a snowball effect of ever-growing validation of my pre-existing beliefs. In some ways this was war that filter bubbles had been waiting for.

Fractal war in Telegram then is the ideal environment for political statements and symbolic expression of one’s political affiliation wrapped into the infrastructure that claims to be the vessel of direct reporting of truth from the ground “as it is.” The constant stream of notifications creates the illusion of presence, a never-ending Netflix series which one can binge-watch, stimulating desire for shock and gore. It is war porn evolved.

Moreover, owing to its innate infrastructure, Telegram has two further unique features: it is an unprecedented platform for an “emergent” media and civil society mobilization and it is the platform that makes the link between the frontline and users almost impossible to censor and sanitize.

Although soldiers and others have in earlier wars taken illicit and often disturbing so-called trophies of battle and from and of those they have killed or captured, or even of bodies of their own side’s fallen, such images and objects, these usually take years or decades before they are discovered, talked about, or shared to a wider audience, for instance in films or documentaries or exhibitions. Yet on Telegram there is a stream of what can only be described as war porn. Never have so many images and videos of the suffering, injured, captured, mutilated and the dead, civilians, and soldiers, so freely and continuously poured out from a battlefield. Watch or subscribe to one of these channels and you will experience the least sanitized war in history.

For example, the “Look for Your Own” channel was created by the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine to identify captured and killed soldiers of the Russian army. Unadulterated photos and videos of the dismembered bodies of presumably Russian soldiers, and captives, but also the bodies of civilians, including naked children. Again, this is a channel you can choose to or not to subscribe to, but which has three-quarters of a million subscribers, with posts copied, shared, emojied, and so on.

The government structure then can partake in war porn with the intent of demoralizing the enemy. However, the Russian public did not become demoralized, rather it realized that Russian state propaganda had some grains of truth, believing that Ukrainians have a desire to “burn Russians” (жечь русню). This channel also spawned and perhaps legitimized numerous potential copycats from the Russian side. And today there are many.

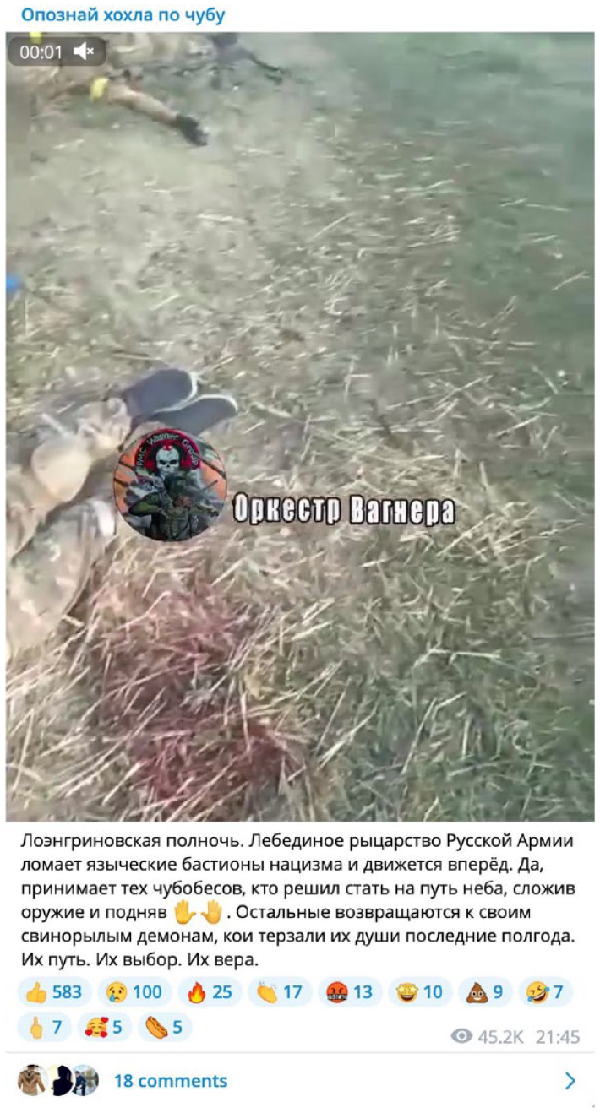

Their names are intended to humiliate Ukrainians and share exactly the same logic as “Look for your own,” such as, “Know Khokla by Chubu” and “Vegetable Raguul.” For example, Figure 1, below shows a Telegram post of the 12th July 2022 on the Russian channel “Know Khokla by Chubu” showing a 22-second video of the bodies on the ground of presumably Ukrainian soldiers accompanied by an operatic score.

Figure 1

Post in the telegram channel “Know Khokla by Chubu,” 12 October 2022.

The Russian text in the post translates into English as:

Lohengrin midnight. The swan chivalry of the Russian Army breaks the pagan bastions of Nazism and moves forward. Yes, it accepts those Chubobes who decided to take the path of heaven, laying down their arms and raising

. The rest return to their pig-nosed demons, which have tormented their souls for the past six months. Their path. Their choice. Their faith.

In the bottom of the post are a range of celebratory emojis and a post view count of 45,200. There is no equivalent to the immediacy and scale of reach of the use of such graphic images of human injury, suffering and death, including in the capacity for engagement by all in the war feed.

Channels like “Look for your own” act as aggregators but they cannot exist without a steady stream of content from all the new smartphone equipped participants in the war feed. This includes nearly every notable Russian and Ukrainian military regiment having its own Telegram channel. These include the Russian “Southfront Intelligence” and “Archangeles of Special forces”—and the Ukrainian “Heroes of 35th Naval Brigade.”

At the same time, Telegram facilitates the mobilization of civil society. Many prominent war bloggers on both the Russian and Ukrainian sides also act as volunteers raising money to support frontline regiments with military equipment of all sorts, from vehicles and uniform to sniper rifles and drones. This feature of Telegram seems to be mostly utilized by the Russian side.

A further appropriation and adaptation of Telegram to this war is the emergence of aggregator channels. A prominent example is ColonnelCassad, which was originally a personal channel of the Russian supporting journalist Boris Rozhin. Originally from the Crimean city of Sevastopol Rozhin supports Russian World doctrine and believes that Cold War never ended and now it is time for Russian revival. He is a good example of the blurring of roles in “radical war” () in that he is enthusiast, journalist and is subsumed into the state’s propaganda machine.

ColonnelCassad, quickly became the key pro-Russian Telegram channel with over 800,000 subscribers. Before the 2022 war, Rozhin was the number one communist blogger in LifeJournal (in May 2021 he had 52,000 subscribers). He invented the meme “polite people” to describe Russian special forces who took Crimea without officially recognizing their Russian affiliation.

Other Telegram channels are less transparent in terms of exactly who is their principal operator, for instance, one of the largest OSINT channels is a Rybar (https://t.me/rybar/35537). This recently had 1,100,000 subscribers and earned a reputation as an honest pro-Russian channel which, offering a mix of stunning infographics, coordinates for air strikes and a critique of the Russian Ministry of Defense.

Crowd-sourcing for humanitarian assistance or military equipment (drones, advanced optics, uniform, bulletproof vests) also has a significant presence on Telegram. For example, OPSB (https://t.me/zola_of_renovation/1569) unites under its umbrella dozens of channels all created by Russian civil society in the broad sense of the word (one of the founders is an immigrant from Odesa, one from the city of Luhansk) who share the ambition to help modernize the Russian army to enhance its efficiency in the fighting of this war.

Telegram as a media ecology, has in part at least, filled the vacuum left by the failure of traditional state-run or influenced mainstream news media. It is civil society, as participant war, that creates original and visually inspiring content (https://t.me/zastavnyii/895).

Finally, there is a spectrum of bloggers, some on the ground in Ukraine, some more remotely, who fill the war feed. These channels range in followers from several million to tens of thousands. Firstly, classical bloggers and journalists (https://t.me/yurasumy/4217; https://t.me/MedvedevVesti/10480). Secondly, there are independent war reporters on the ground (https://t.me/wargonzo/7517). Thirdly, there are reporters that are accredited by the Russian Ministry of Defence (https://t.me/epoddubny/11532). And fourthly there are also established and well-known traditional journalists who have recognized the potential of Telegram for their own outputs and reputation (https://t.me/SolovievLive/116811).

In sum, Telegram is a unique media ecology in its openness to and exploitation by an array of individuals, civilian society groups, NGOs, journalists, militaries, and states, in the prosecution of war. Telegram is unlike other social media platforms or networks in its structure, as we have already outlined, but also in its adaptation and weaponization. War on Telegram is not like a traditional platform with owners or regulatory pressures, or relatedly perceptions around or coverage of mainstream outrage, suppressing or removing explicit or extreme content. There is no semblance of a sense of any pursuit of a media standard to test or to conform to, legitimacy, or of “taste and decency,” or of a search for ways to separate out information, misinformation, and disinformation.

Rather, Telegram is the perfect example of how war accelerates into media. This media ecology is a new battlespace in which participants exploit extreme, unregulated, uncensored, and unsanitized opportunities to push their version and vision of war. Telegram, like many media ecologies, is highly connected to an array of other media (including mainstream) platforms, to and from which content is shared, re-used, re-purposed, and re-weaponized. Yet, Telegram is nonetheless also a highly contained ecology of media in being a place where anything goes, streaming the most graphic images of human abuse, injury and death, ever disseminated from a war so immediately, so continuously and at such a scale (in terms of the volume of images and video, and the numbers of subscribers).

Whilst the continuous stream of the war feed shapes immediate perceptions on the ground and around the globe, we now turn to consider the possible trajectories of this astonishing glut of digital media content of war. Is it that all so much information and disinformation available about war with such immediacy, recorded via smartphone and satellites, shared via chat and messaging apps and an array of social media platforms, will ultimately offer an impenetrable memory and history? Does the saturating, yet also at the same time, the splintering of attention, of the war feed, leave something that will endure and offer an accessible, mineable, and ultimately usable archive for the shaping of memory and of history?

The Most Documented Event in History

Only 6 months after the tragedy of the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001, a television documentary described this event as “the most documented event in history” ().

To repeat then what Hoskins said in several talks around the time, this was an extraordinary claim. What about the Holocaust, or the First World War, or the death of John F. Kennedy? Surely these events have accumulated more documentation, more commentary, documentary, artworks, and archives and so on, in the time since their unfolding? Of course, why this claim was made about 9/11 at the time was partly because the attacks on the United States were recorded and broadcast live on global TV and in the early days of cheaper portable recording devices, but also as an existential shock to the US, but also to its media, and so much of the country couldn’t let the story begin to slip from its mainstream headline news until a year later ().

But recently, using this claim as to the most documented event in history seems less extraordinary. The war in Ukraine is being rendered through pre-existing but also highly adaptive media ecologies, as we have shown. This is a hyperconnected environment in which smartphones, apps, and platforms, feed the outrageous, the extremes, notably all that rendered contagious in informational warfare. For example, soon after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, it was clear that the short-form video messaging platform TikTok was “designed for war.” This was particularly in its ease of use and its visual immediacy in feeding footage from the battlefield to billions of users, but also in how it spread to other platforms such as Twitter and other mainstream media channels. But this is only a glimpse of the digital transformation of war as it shapes remembering and forgetting at a new scale.

Whilst there is a slippage in our capacity to render the shifts in the scale and complexity of the digital and datafied production of the present intelligible, at the same time this digital production of the present shapes a paradoxical haunting, yet also forgetting, in the future.

The recording, documentation, storing, archiving, but also sharing (and paradoxically) losing of representations of and information about the past has never been easier. Events, personal and professional, insignificant and momentous, unfold and are experienced within these new extended parameters of the past.

New infrastructures of remembrance, awaiting the digestion of the incoming present, determine if and what and how of the future will be available and used or abused. There is a kind of “structural virality” to how the past is forged, circulated, shared, deposited, and archived. The very surface and transactions of social life seem informational, increasingly dependent on data and networks and bandwidth to meet the demands for frictionless existence. So, the will to remember meets the technological will to capture, share, and archive. Together these forces unleash an unprecedented new platform for the present to become past in the future. The structural virality of memory is also a matter of haste as well as speed, volume, contagion and connectivity. And these are precisely the circumstances, the media ecologies, through which the Russian war against Ukraine is being experienced.

One of the significant transformations in how the media of an event is translated into the memory of an event, from the last century to this one, is that no-one waits to memorialize anything anymore. This is part of a wider shift in a more immediate turn to the past, and also a turn on the past. To offer some historical context, this can be seen in terms of our living through a period of a “memory boom,” in which remembering and forgetting can be seen tied to both the nature of warfare, and also to the technological transformations in the media of representation, communication, and archiving of the day.

Crises and catastrophes often seen as synonymous with memory of the 20th century (and particularly world wars) initially marked by periods of limited and mostly private recollection, silence, denial, unspoken trauma and non-memory, were only publicly and officially commemorated or memorialized at scale many years later. The first two “memory booms” are related to the formation of national identities after the First World War and to the sudden expansion in Holocaust remembrance in the late 20th century (, ).

write of a “third memory boom,” more typical of early 21st century remembrance, where the memorializing of an event is increasingly entangled with the unfolding of the event itself, so what an experience means at the time is shaped more through more immediate attempts to determine (and indeed conflict over) how an event should and will be remembered or commemorated.

For example, the Kiev tourist board has created a virtual museum of war memory, which is kind of surreal as well as horrific. It is even more surreal if you click on the links to places and promotional tours which depicts Ukraine in its former, pre-2022 war state. The website declares:

We are sure that after the victory we will rebuild everything, and Kyiv region will again become a place to live, where everyone will want to have a house, engage in active tourism, taste delicious food from local farmers or retire to an ethnic estate in nature.

But we will never be able to forget what happened. That’s why the VR Museum of War Memory was created. With the help of 3D tours, visitors will be able to get into the terrible reality that the war brought with it to Irpen, Bucha, Gostomel, Gorenka and other towns and villages.

And thus, the third memory boom, is driven by a desire to stop forgetting, even if it is more immediate.

But while the third memory boom is intensifying in some ways, at the same time, there are shifts toward something new. Some responses to the unfolding war in Ukraine seem to take memory as we understand it to a new place. This unfolding in and shaping a fourth memory boom becomes detached from any kind of reality of the past. This is memory of the present for the present, rather than in any practical sense a memory of the present for an ever realizable human future.

This we suggest is part of a tipping point in which datafied societies are overwhelmed by an over-production of the self, experiences, events, resulting in a glut of media content of unmanageable complexity and scale. The very existence and state of human memory is thus under threat from a cycle of our growing dependency on digital devices, systems, networks, archives, and content for remembrance, whilst at the same time this digital life slips beyond human intelligibility. This results in what calls “the broken past.”

This is a digitally compromised memory, one that whilst appearing under the control of our digital devices and apps, is already lost to the algorithmic processes and the vagaries of their design and operation. The past is broken in that what will become encoded into individual and social memory and what will not is increasingly determined by digital nudging (). The provenance of the (social media) archive becomes increasingly difficult to secure.

Platforms and apps differ markedly in what can be downloaded and archived and analyzed and remembered. In other words, it is how digital technologies enable or disable individuals, organizations, groups, or whoever, to encode memories in the first place, which shapes what will ultimately be even possible to see again, to re-represent, to remember. The past becomes broken when so little of the present is effectively encodable into usable future memory, it is just not accessible as memory ().

This battle over this “new memory” () includes that taken up by organizations dedicated to the collection, archiving, memorializing and analysis of digital information, documenting human rights violations and international crimes, such as Mnemonic and Bellingcat. In terms of the scale of digital content these are also new guardians of the emergent archives and remembrance of war.

For much of the late twentieth and into the early 21st century, the relationship between war and media was imaginable and knowable for many through its potential archives of print, sound, televisual, and film records. There was once a relatively finite sense of collecting, mining and understanding of the archival record of the media documenting of events (e.g., ).

Today the long-standing relationship between event, media, archive, meaning, and memory, has been utterly transformed. For example, the NGO Mnemonic, who preserve documents of alleged human rights violations and other serious crimes, over the ten years of the Syrian war gathered 40 years of footage, that’s around 3.5–4 million records. Each record is a tweet, message, image, or video. For Ukraine in 2022, in just the first 80 days of the war, Mnemonic had already gathered half a million records, that’s a decade of footage. And these are only materials of a particular nature gathered by one NGO for a particular purpose, so this is only a fraction of content that is actually in existence relating to recording of this war.

What then, does all this volume add up to, how when and where will it be used and by who? For instance, , p. 179) suggests of all of the digital content of atrocities being collected by NGOs and an array of organizations pursuing justice and accountability, “It is as much archive as we have ever had relating to torture, mass murder, and war crimes. And it sits there, waiting for facts to be given meaning.”

The astonishing volume of availability of digital content then prohibits a meaningful memory of warfare from coming into being. The unfolding war in Ukraine seems incredibly available in real-time coverage on an array of devices, platforms, and media, but what is actually humanly accessible and intelligible?

The potential for the collected archive to be mined and remined anew, for new purposes to new ends, has never been greater. This of course, could be useful in the prosecution of international law such as war crimes and breaches of the Geneva convention. Nonetheless, there is the need for the international political will and the financial resources to prosecute war crimes at scale. And despite the mass accumulations of archives and evidence through the war feed, political and public attention tends to follow a diminishing trend. At a cultural and collective level, we are left with, in Pomerantsev’s terms (above), archives without meaning. What the present might look like in the future and what it might be used for, is now increasingly in the hands of private companies and platforms, and their interrelations with militaries, and with states.

Conclusion

Soldiers, civilians, journalists, victims, aid workers, presidents, journalists, are all recording and uploading their experience and vision of events second by second, tracking every twist and turn. The battlefield seems open to all in the war feed. At the same time, digital media offer new potential for an amazingly rich future memory and history of the experience and consequences of warfare. And the millions of messages, images, and video, pouring out of the smartphones in Ukraine, surely makes this the most documented and the most personalized war to date.

The idea of the war feed is useful as it captures the sense of the separate individual seeing and engaging or ignoring war through their continuous digital feed of media, to which they both subscribe and share (for other subscribers). This is the splintering of perceptions of war.

Although war often accelerates into the media of the day, the war feed goes beyond many of the traditional mainstream modes of the representation of events and experiences. As , p. 13) argues, “Most of all an acceleration of warfare. . . include[s] an important metabolic dimension—an approaching generalized war on the biological terrain of wetware—psychology, subjectivity, and affect.” Yet at the same time as war is individualized in this way, it is also massified. The numbers of subscribers to a given channel, the number and kind of individual responses to each individual post, and in turn the responses to the responses, affords a new scale of billions of users, a “new mass,” a digital multitude rather than any kind of unifying collective. Just from our example from Telegram (Figure 1) above we can see over 45,000 views of this individual post, in a stream of thousands of others, within a matter of hours.

The war feed renders the war in and against Ukraine up close and personal. Never have so many images and videos of human suffering and death in war been so quickly available, streaming from the battlefield. Nor has such media content ever been weaponized so quickly and on such a scale, as trophies, as propaganda, as blunt psychological warfare. This weaponization is also crowd-sourced. A digital multitude posting, liking, sharing and applauding each individual image or short form video, are all participants engaged in a fractalized psychological war.

Meanwhile, the mainstream media look on. Or rather they look past Telegram, unable to show what is shown there. The debates over why and how social media platforms should be moderated, regulated, or outlawed in response to claims as to their seeding of misinformation, disinformation, propaganda, and much of that content, which is generally pixelated on mainstream news outlets, if used at all, have intensified in recent years. Yet, an unsanitized and uncensored war rages on, in plain sight.

What will become of the record of this war, how it will be shown and not shown, legitimized and contested, remembered and forgotten, and all the ways in which it might be encoded into individual and social memory, remains to be seen. But the war feed is no panacea for either understanding or remembrance. This is a war that despite its astonishing personalization and documentation, through its digital capturing, sharing, and exposure, may yet become easily forgotten.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Andrew Hoskins

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1207-2728

1. See .

2. See on “participative” and “digital war.”

3. For a comprehensive account of the history of competing versions of “media ecology” and its theoretical influences and uses, see .

4. See important study of particularly pro-genocidal comments and reactions on Telegram during the initial stages of the Russian war against Ukraine.

5. Translation from Russian to English by Pavel Shchelin.

6. https://www.wired.co.uk/article/ukraine-russia-war-tiktok

7. https://kyivregiontours.gov.ua/en/war

8. Ibid.

9. Jeff Deutch, Mnemonic, interviewed by Andrew Hoskins.

10. Andrew Hoskins and Ben O’Loughlin have discussed over many years the idea of the existence and nature of a “new mass” in digital societies.

References

- Awan A., Hoskins A., O’Loughlin B. (2012). Media and radicalisation: Connectivity and terrorism in the new media ecology. Routledge.

- Begon M., Townsend C. R., Harper J. L. (2003). Ecology: From individuals to ecosystems. Blackwell Publishing.

- Ford M., Hoskins A. (2022). Radical war: Data, attention and control in the twenty-first century. Hurst/Oxford University Press.

- Fuller M. (2007). Media ecologies. MIT Press.

- Hoskins A. (2004a). Televising war: From Vietnam to Iraq. Continuum.

- Hoskins A. (2004b) Television and the collapse of memory. Time & Society, 13(1), 109–127.

- Hoskins A. (2011). 7/7 and connective memory: Interactional trajectories of remembering in post-scarcity culture. Memory Studies, 4(3), 269–280.

- Hoskins A. (2021). Media and compassion after digital war: Why digital media haven’t transformed responses to human suffering in contemporary conflict. International Review of the Red Cross, 102(913), 117–143. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1816383121000102.

- Hoskins A. (forthcoming). Breaking the past. Oxford University Press.

- Hoskins A., Čimová K. (forthcoming) Is memory finished? The digital nudging of the past. MIT Press.

- Hoskins A., O’Loughlin B. (2010). War and media: The emergence of diffused war. Polity Press.

- Hoskins A., Tulloch J. (2016). Risk and hyperconnectivity: Media and memories of neoliberalism. Oxford University Press.

- Kroker A. (2014). Exits to the posthuman future. Polity Press.

- McLuhan M. (1964). Understanding media: The extensions of man. Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Merrin W. (2014). Media studies 2.0. Routledge.

- Merrin W. (2018). Digital war: A critical introduction. Routledge.

- Pomerantsev P. (2019). This is not propaganda: Adventures in the war against reality. Faber & Faber.

- Postman N. (1970). ‘The reformed English curriculum.’ In Eurich A. C. (Ed.), The shape of the future in American secondary education (pp. 160–168). Pitman Publishing Corporation.

- Strate L. (2006). Echoes and reflections: On media ecology as a field of study. Hampton Press.

- Winter J. (2006). Remembering war: The Great War between memory and history in the twentieth century. Yale University Press.

- Winter J. (2017). War beyond words: Languages of remembrance from the Great War to the present. Cambridge University Press.