WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Previous research has established a relationship between short sleep duration and school absences.

The connections of excessive internet use, short sleep and physical activity (PA) with school absences have remained unclear.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Excessive internet use was associated with an increased risk for both unexcused and medical absences from school, while longer sleep duration and higher PA showed a protective association.

A trusting relationship with parents emerged as an important protective factor for both unexcused and medical absences.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Highlights the vitality of collaboration between health and education sectors to improve long-term health outcomes among adolescents.

Introduction

Education is an essential determinant of future health for adolescents, but it can be jeopardised by school absences. School absences can be either unexcused (also called truancy) or excused, most commonly for medical reasons. School absences can be caused by physical and mental health problems, but they may also be associated with different types of risky behaviour or an unhealthy lifestyle involving excessive use of screen-based media, insufficient sleep and limited physical activity (PA).

The internet, online gaming and the upsurge of social media during the last decade have dramatically changed the lives of adolescents. Among adolescents, excessive gaming and social media use have been associated with school absences, poor numeracy skills, anxiety and poorer sleep. Although variance between assessment instruments of excessive internet use (EIU) complicates comparisons, digital media may be a factor tempting adolescents to stay home from school, and may also hinder learning through lack of sleep.

Sleep is necessary for all aspects of health and development. To promote optimal health, adolescents aged 13 to 18 should sleep 8–10 hours per night. Meta-analyses have found that insufficient or disturbed sleep among children and adolescents is associated with obesity and depressive symptoms. Insufficient sleep and poor sleep quality are also associated with poor educational attainment, possibly through school absences. The direct impact of sleep on unexcused and medical absences, however, remains unclear.

Besides contributing a positive impact on general health throughout the life course, regular PA is important for the brain health of school-aged children and adolescents because it improves both cognition and mental health. Adolescents should engage in 60 min or more of moderate-to-vigorous PA daily. No consensus has been reached on the association of PA with school absences. Some studies have found higher rates of absences in both inactive and highly active children than among children with medium levels of PA. De Groot et al found no direct association between PA and medical absences from school.

The objective of this study was to examine the associations of EIU, short sleep and PA with unexcused absences and medical absences from school among adolescents. We hypothesised that EIU would be associated with a higher risk of both unexcused and medical absences, whereas sleep and PA would have a protective association.

Methods

Study population and procedure

This study used data from the School Health Promotion study, a national biennial survey conducted in Finland and managed by the Institute for Health and Welfare. All students in years 8 and 9 and present at school on the day of the survey administration are invited to participate. Both adolescents and their parents may opt out of participation. An anonymous survey was administered to adolescents in classrooms, with both online and pen-and-paper options available, and under teacher supervision. In this study, we utilised responses from the nationally representative sample of year 8 and 9 students in 2019, when EIU was assessed for the first time. These age cohorts comprised 118 178 adolescents, of whom 86 283 (73.0%) participated. Responses were geographically evenly distributed and considered nationally representative.

In Finland, education is compulsory and free of charge from the year a child turns seven until age 18 years. In school years 8 and 9, students are typically 14–16 years old. As advised by the Institute for Health and Welfare, we excluded responses if self-reported age was below 13 or exceeded 18. Year 9 marks the end of lower secondary school, and during the spring term students apply to either academic upper secondary school or vocational education. Thus, school absences in lower secondary school have special significance.

Measures

Demographics

Self-reported gender was based on the two response options (boy or girl) to the question ‘What is your official gender?’ Students also reported their school year.

Socioeconomic status was based on maternal education level, reported by the students. The question ‘What is the highest educational level your mother has achieved?’ had four response options: ‘comprehensive school or equivalent’ (meaning 9 years of education), ‘upper secondary school, high school or vocation education’ (meaning 12 years of education), ‘occupational studies in addition to upper secondary school, high school or vocational education’ and ‘university, university of applied sciences or other higher education’.

One question, ‘Can you talk about things that concern you with your parents?’, described parental relations. Response options were ‘hardly ever’, ‘occasionally’, ‘fairly often’ and ‘often’.

Excessive internet use (EIU)

The EIU scale is short and has shown good internal consistency in previous studies. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.77 overall and 0.74 in Finland. The EIU scale has five statements: ‘I have tried spending less time online but I have failed’, ‘I should spend more time with my family, friends or doing homework, but I spend all my time online’, ‘I have found that I was online even though I did not really feel like it’, ‘I have felt anxious when I do not get online’ and ‘I have failed to eat or sleep because of being online’. Respondents were asked to estimate how often they experienced each of the above on a four-point Likert scale from ‘never’ to ‘very often’, which translated to numeric values of 1–4. EIU was defined as the mean value of the five scores.

Sleep duration

Sleep duration was calculated from two questions: ‘At what time do you usually go to bed?’ and ‘At what time do you usually wake up?’ For both questions, responses were collected separately for weekdays and weekends. Response options for bedtime were provided at half-hour intervals from ‘about 7 p.m. or earlier’ to ‘about 4 a.m. or later’. Response options for wake-up times were also at half-hour intervals from ‘about 5 a.m. or earlier’ to ‘about 1 p.m. or later’.

Physical activity (PA)

PA was assessed through two questions. The first measured overall PA: ‘Think about all the moving around you have done over the past 7 days. On how many days have you been on the move for at least 1 hour per day?’ Response options ranged from zero to 7 days. The second question evaluated vigorous PA: ‘During your spare time, how many hours per week do you usually engage in physical exercise that causes shortness of breath and sweating?’, and response options were ‘none’, ‘about 0.5 hours’, ‘about 1 hours’, ‘about 2–3 hours’, ‘about 4–6 hours’ and ‘about 7 hours or more’.

Unexcused and medical absences from school

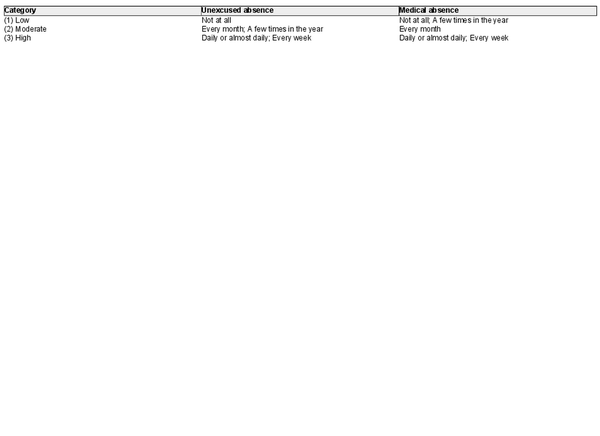

The question ‘During this school year, how often have you experienced the following’ had two subcomponents: ‘Being absent without permission, skipping school’ and ‘Absences due to illness’. Both had the same five response options: ‘not at all’, ‘a few times in the year’, ‘every month’, ‘every week’ and ‘daily or almost daily’. Because some medical absences are natural and unexcused absences have been associated with delinquent behaviour, unexcused and medical absences were classified slightly differently into three categories.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics included percentages and means (with SD). Gender differences were estimated with independent sample t-tests and odds ratios. Cumulative odds ratio (COR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was used to measure the association of independent variables (gender, school year, maternal education, parental relations, EIU, sleep duration on weekdays and weekends, overall and vigorous PA) with unexcused and medical absences separately. For ordinal variables, CORs were calculated pairwise, with each category compared separately with the reference category. First, if COR >1, the distribution of absence is more concentrated to ‘higher’ values in the first category of the categorical independent compared with the reference category. Second, this concentration increases when a numeric independent has greater values. We ran the analyses separately for genders, but since CORs were mostly similar for both genders, overall CORs are presented and the few significant differences between genders are flagged. Model fit was estimated using Somers’ D. Results are reported as unstandardised estimates, and p<0.05 was considered significant. Analyses were conducted using Mplus version 8.7 and SAS 9.4.

Missing data

Data availability is reported for all variables separately. Since the proportion of missing data for different variables was low, complete cases were used in COR calculations.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Working Group on Research Ethics of the Institute for Health and Welfare (THL/1578/6.02.01/2018 §807).

Results

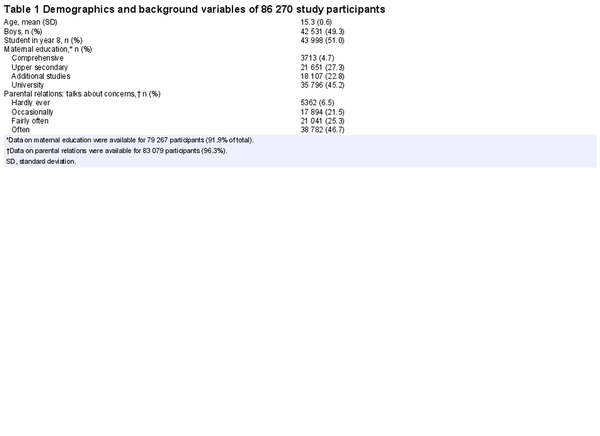

The 86 270 participants (response rate: 73.0% of respective age group) showed even gender and age distribution (table 1). Mothers most commonly had university or other higher-level education, and parental relations were most often good.

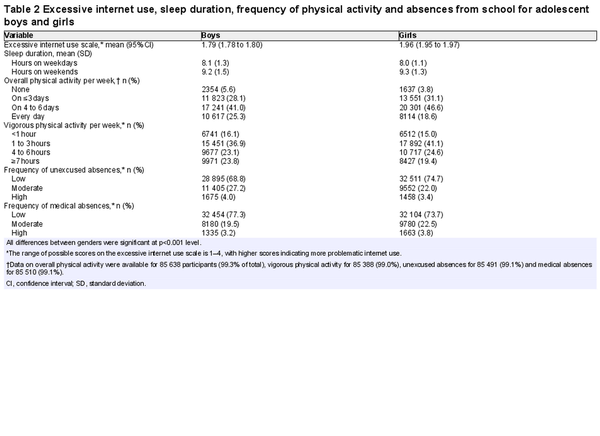

The EIU scale average score was 1.9 (SD 0.7; table 2). Girls yielded a higher EIU score than boys (2.0 vs 1.8; p<0.001, Cohen’s d=0.4), and 1881 participants (2.3%) reported the maximum EIU score of 4.

Participants slept an average of 8.0 hours per night during the school week, and 9.2 hours per night during the weekend (table 2). More than one-third (34.7%) slept less than 8 hours per night on weekdays, and 10.9% slept less than 8 hours per night on weekends.

Participants reported overall PA on average on 4 days during the preceding week and vigorous PA for 2–3 hours per week. Among boys, both no PA and daily PA were more frequent than among girls (table 2).

In all, 3.2–4.0% of the study population reported high rates of school absences (table 2). Boys reported more unexcused absences than girls did, while girls reported more medical absences than boys did (p<0.001 for both).

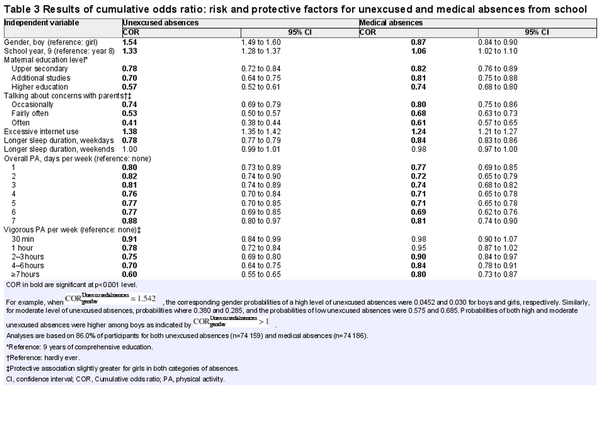

In cumulative odds ratio, EIU was associated with an increased risk for both unexcused and medical absences (table 3). Older age was associated with an increased risk of unexcused absences. Maternal education level, parental relations (talking about concerns with parents), longer sleep duration during weekdays and PA showed a significant protective dose–response relationship with both unexcused and medical absences from school. Talking about concerns with parents often showed the strongest protective association. Overall, the model fit was moderate (0.35) for unexcused absences and low (0.22) for medical absences.

Discussion

In this nationally representative population-based study, adolescent girls reported more excessive internet use (EIU) than did boys, more than one-third of adolescents slept less than 8 hours per night during the school week and more than half of adolescents engaged in vigorous exercise for less than 3 hours weekly. EIU, short sleep duration during weekdays and low PA were all associated with both unexcused and medical absences from school among 14–16 year old students. Talking about concerns with parents often emerged as the strongest protective factor for both unexcused and medical absences.

Of the study participants, 2% yielded a maximum score for EIU. Previous studies have reported a prevalence of 6% for problematic mobile phone use. The EIU specifically reflects the symptoms of addiction instead of measuring excessive time spent online. Girls scored higher than did boys on the EIU scale. We suspect this may be due to social media, which girls use more than boys. A recent meta-analysis supported the hypothesis that different patterns of internet addiction may be seen among men and women.

Shorter sleep duration especially during the school week showed direct associations with unexcused and medical school absences. Short sleep (less than 8 hours per night) during the school week showed a significant independent association with school absences, and this association was not compensated by longer sleep during weekends. This is in line with previous research, where weekend recovery sleep failed to protect against metabolic dysregulation.

Overall PA was associated with both unexcused and medical school absences: the more frequent light PA was, the fewer absences the adolescents reported. When PA was reported daily, however, the protective association of PA was smaller than for any other frequency of PA. It seems logical that a break is also needed from PA for optimal well-being. In all, the findings between PA and school absences may reflect that adolescents who are supported to commit to a physically active lifestyle are also supported to attend school. We also found a stronger relationship between overall than vigorous PA and fewer medical absences. Potentially a more active general lifestyle is healthier than a modern combination of a sedentary lifestyle and competitive sport hobbies.

In this study, a trusting relationship with parents was the strongest protective factor against school absences. Nearly half of the study participants reported that they often talk with their parents about their concerns. Trusting, open relationships between parents and their adolescent children also protect them against EIU. Furthermore, adolescents also need their parents’ support to maintain a regular sleep schedule, because longer sleep during weekends is insufficient to protect against school absences.

The strengths of this study include a large, population-based cohort with a high participation rate, and distinguishing between unexcused and medical absences from school. Participation rates were even geographically and across schools in cities. The first limitation is the cross-sectional, self-reported nature of data, and thus, causal relationships cannot be determined. The most important group of non-participants were adolescents who were absent from school on the day of data collection. This could plausibly have included students with high rates of absences, which may cause bias especially in a study focusing on absences from school. When comparing our dataset with national statistics, the proportion of boys was slightly lower than among the entire population (49.3% vs 50.9%, respectively). Our proxy measure for socioeconomic status was maternal education. At population-level, education is only collected based on age and gender instead of parenthood. The study participants reported a higher frequency of university level education among their mothers than recorded among women aged 35–54 at the population-level in Finland (45.1% vs 42.2%, respectively). Childlessness is, however, more common among persons with low or medium education, and thus, potential bias associated with socioeconomic status remains unknown. The School Health Promotion study included no information on the type of internet use adolescents engaged in, and thus, no conclusions can be drawn related to gaming and social media. In this study, we only utilised data on the self-reported official gender, but population-based research on adolescents identifying as non-binary is urgently needed.

Despite its limitations, our results have important implications for promotion of health and education attainment. Our results are relevant for professionals organising and working in school health and well-being services, especially when professionals meet students whose school absences raise concern. Besides direct school-related factors, the lifestyle factors associated with absences should also be assessed, and support should be provided according to need.

X @SiljaKosola

SK and MK contributed equally.

Contributors SK: conception, design, interpretation of results, first draft, revisions, guarantor. MK: conception, data curation, interpretation of results, revisions. KM: conception, interpretation of results, revisions. JE: data acquisition, statistical analyses, interpretation of results, revisions. KR: conception, design, interpretation of results, revisions. KA: conception, design, data acquisition and curation, interpretation of results, revisions. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding Silja Kosola was supported by a grant from The Foundation for Pediatric Research. Marianne Kullberg was supported by a grant from The Swedish Cultural Foundation in Finland, grant number 180773. Klaus Ranta was funded by the Strategic Research Council established within the Academy of Finland to the Imagine Research Consortium, grant number 352700, and to Tampere University, grant number 353048. Katarina Alanko was funded by the C.G. Sundell Foundation. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, decision to publish, or in writing the manuscript.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Gubbels J, van der Put CE, Assink M. Risk factors for school absenteeism and dropout: a meta-analytic review. J Youth Adolesc 2019;48:1637–67. doi:10.1007/s10964-019-01072-5

- 2. Alanko K, Melander K, Ranta K, et al. Time trends in adolescent school absences and associated bullying involvement between 2000 and 2019: a nationwide study. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev , 2023. doi:10.1007/s10578-023-01601-1

- 3. Ruckwongpatr K, Chirawat P, Ghavifekr S, et al. Problematic Internet use (PIU) in youth: a brief literature review of selected topics. Curr Opin Behav Sci 2022;46:101150. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2022.101150

- 4. US Surgeon General. Social media and youth mental health. The US surgeon general’s advisory. 2023. Available: https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/priorities/youth-mental-health/social-media/index.html [Accessed 17 Dec 2023].

- 5. Rehbein F, Kliem S, Baier D, et al. Prevalence of Internet gaming disorder in German adolescents: diagnostic contribution of the nine DSM-5 criteria in a state-wide representative sample: internet gaming disorder in adolescents. Addiction 2015;110:842–51. doi:10.1111/add.12849

- 6. Gentile DA, Bailey K, Bavelier D, et al. Internet gaming disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2017;140:S81–5. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1758H

- 7. Schwartz D, Kelleghan A, Malamut S, et al. Distinct modalities of electronic communication and school adjustment. J Youth Adolescence 2019;48:1452–68. doi:10.1007/s10964-019-01061-8

- 8. Su W, Han X, Yu H, et al. Do men become addicted to Internet gaming and women to social media? A meta-analysis examining gender-related differences in specific Internet addiction. Comput Hum Behav 2020;113:106480. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2020.106480

- 9. Mundy LK, Canterford L, Hoq M, et al. Electronic media use and academic performance in late childhood: a longitudinal study. PLoS One 2020;15:e0237908. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0237908

- 10. Doll JJ, Eslami Z, Walters L. Understanding why students drop out of high school, according to their own reports: are they pushed or pulled, or do they fall out? A comparative analysis of seven nationally representative studies. SAGE Open 2013;4:3. doi:10.1177/2158244013503834

- 11. Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D’Ambrosio C, et al. Consensus statement of the American Academy of sleep medicine on the recommended amount of sleep for healthy children: methodology and discussion. J Clin Sleep Med 2016;12:1549–61. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6288

- 12. Fatima Y, Doi SAR, Mamun AA. Sleep quality and obesity in young subjects: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2016;17:1154–66. doi:10.1111/obr.12444

- 13. Marino C, Andrade B, Campisi SC, et al. Association between disturbed sleep and depression in children and youths: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e212373. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.2373

- 14. Hysing M, Haugland S, Stormark KM, et al. Sleep and school attendance in adolescence: results from a large population-based study. Scand J Public Health 2015;43:2–9. doi:10.1177/1403494814556647

- 15. Matos MG, Gaspar T, Tomé G, et al. Sleep variability and fatigue in adolescents: associations with school-related features. Int J Psychol 2016;51:323–31. doi:10.1002/ijop.12167

- 16. Kim J, Park GR, Sutin AR. Adolescent sleep quality and quantity and educational attainment: a test of multiple mechanisms using sibling difference models. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2022;63:1644–57. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13686

- 17. Rodriguez-Ayllon M, Cadenas-Sánchez C, Estévez-López F, et al. Role of physical activity and sedentary behavior in the mental health of preschoolers, children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med 2019;49:1383–410. doi:10.1007/s40279-019-01099-5

- 18. US Department of Health and Human Services. Active children and adolescents. In physical activity guidelines for Americans, second edition. Washington, DC US Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/physicalactivity/guidelines

- 19. Hansen AR, Pritchard T, Melnic I, et al. Physical activity, screen time, and school absenteeism: self-reports from NHANES 2005-2008. Current Medical Research and Opinion 2016;32:651–9. doi:10.1185/03007995.2015.1135112

- 20. de Groot R, van Dijk M, Savelberg H, et al. Physical activity and school absenteeism due to illness in adolescents. J Sch Health 2017;87:658–64. doi:10.1111/josh.12542

- 21. Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. School health promotion study. Available: https://thl.fi/en/web/thlfi-en/research-and-development/research-and-projects/school-health-promotion-study [Accessed 29 May 2023].

- 22. Blinka L, Škařupová K, Ševčíková A, et al. Excessive Internet use in European adolescents: what determines differences in severity? Int J Public Health 2015;60:249–56. doi:10.1007/s00038-014-0635-x

- 23. Škařupová K, Ólafsson K, Blinka L. Excessive internet use and its association with negative experiences: quasi-validation of a short scale in 25 European countries. Comput Hum Behav 2015;53:118–23. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.06.047

- 24. Sahu M, Gandhi S, Sharma MK. Mobile phone addiction among children and adolescents: a systematic review. J Addict Nurs 2019;30:261–8. doi:10.1097/JAN.0000000000000309

- 25. Griffiths M. A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. J Subst Use 2005;10:191–7. doi:10.1080/14659890500114359

- 26. Svensson R, Johnson B, Olsson A. Does gender matter? The association between different digital media activities and adolescent well-being. BMC Public Health 2022;22:273. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-12670-7

- 27. Booker CL, Kelly YJ, Sacker A. Gender differences in the associations between age trends of social media interaction and well-being among 10-15 year olds in the UK. BMC Public Health 2018;18:321. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5220-4

- 28. Depner CM, Melanson EL, Eckel RH, et al. Ad libitum weekend recovery sleep fails to prevent metabolic dysregulation during a repeating pattern of insufficient sleep and weekend recovery sleep. Current Biology 2019;29:957–967. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.01.069

- 29. Cadenas-Sanchez C, Mena-Molina A, Torres-Lopez LV, et al. Healthier minds in fitter bodies: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between physical fitness and mental health in youth. Sports Med 2021;51:2571–605. doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01520-y

- 30. Melander K, Kortteisto T, Hermanson E, et al. The perceptions of different professionals on school absenteeism, and the role of school health care: a focus group study conducted in Finland. PLoS One 2022;17:e0264259. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0264259

- 31. Launay F. Sports-related overuse injuries in children. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2015;101:S139–47. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2014.06.030

- 32. Zhu Y, Deng L, Wan K. The association between parent-child relationship and problematic Internet use among English- and Chinese-language studies: a meta-analysis. Front Psychol 2022;13:885819. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.885819

- 33. Statistics Finland. Educational structure of population. Available: https://stat.fi/en/statistics/vkour [Accessed 17 Dec 2023].

- 34. Jalovaara M, Miettinen A. The highly educated often have two children – childlessness and high numbers of children more commonly seen among low- and medium-educated persons. FLUX policy brief – knowledge to support better decision making 1/2022. Available: https://fluxconsortium.fi/the-highly-educated-often-have-two-children-childlessness-and-high-numbers-of-children-more-commonly-seen-among-low-and-medium-educated-persons [Accessed 17 Dec 2023].