Introduction

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) was developed in the United States in 1979 by Ponski et al. [, ]. Subsequently, the number of gastrostomies increased rapidly, as PEG is less invasive and easier to perform than surgical gastrostomy, which was traditionally performed. In Japan, the number of PEGs has been increasing since 2000. However, since 1990, studies from Europe and the USA have reported an extremely poor long-term prognosis with PEG [-]. In a report of 81,105 cases by Grant et al. [], the overall survival rates at 30 days and 1 year were 76.1 and 37%, respectively. Furthermore, Sanders et al. [] reported survival rates of 46 and 10% in patients with dementia at 30 days and 1 year after PEG, respectively.

In 2010, a large-scale multi-institutional study on PEG, conducted in Japan, reported the long-term prognosis of gastrostomy. The survival rates at 30 days and 1 year were 95 and 66%, respectively, which were better than those in the reports from the USA and Europe []. Moreover, the presence or absence of dementia and its degree do not affect survival after gastrostomy []. The Japan Geriatrics Society 2012 proposed guidelines for determining whether to introduce, withdraw, or withhold artificial hydration and nutritional support in older patients []. The statement stipulated that terminally ill older individuals are entitled to appropriate medical care in consideration of their characteristics and condition. It was also recommended that the indications for tube feeding, including gastrostomy, and the placement of artificial respiration should be carefully considered, and that withholding or withdrawal of treatment should be considered if it might compromise the patient’s dignity or increase their suffering. Subsequently, there was extensive media coverage on end-of-life care, in which gastrostomy was treated as a symbol of futile life-prolonging treatment [].

Consequently, the number of gastrostomies continuously decreased, such that the number of gastrostomies in 2015 was less than half of that in 2011 []. Recently, the use of selective nasogastric tube feeding and total parenteral nutrition without gastrostomy has been increasing in Japan [, ]. Thus, patients who may benefit from gastrostomy currently select other procedures for nutritional support. The aim of this study was to investigate the safety of PEG as a nutritional support method. The procedure-related complications and survival rate of PEG cases conducted at Juzenkai Hospital were examined.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Study Design

A single-institution retrospective cohort study was conducted. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of Juzenkai Hospital (J2020-1). Instead of obtaining informed consent from each patient, notices about the design of the study and other information were posted in public spaces in the hospital as per the guidelines from the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan []. In total, 256 PEG cases were performed from 2005 to 2017 at Juzenkai Hospital, with an average of 20 gastrostomies annually. The medical records of 7 of 256 cases were missing. Therefore, 249 cases were considered. Procedure-related complications and survival rates after PEG were examined. The survey started in March 2018 and ended in December 2018.

PEG Procedure

PEG was originally performed using the pull method [] (Bard PEG Kit Safety System; Medicon Inc., Osaka, Japan). Starting in mid-2011, dual gastropexy was performed using the Funada-style gastric fixation device [] (Create Medic Co., Ltd., Yokohama, Japan), and PEG was performed using a modified introducer method [] (EndoViveTM Seldinger PEG Kit; Boston Scientific Japan, Tokyo, Japan). From 2009, abdominal ultrasound was used at the time of PEG to determine the construction site. On the day before PEG, endoscopy was performed to determine whether PEG could be safely performed. From 2013, abdominal computed tomography was performed on all patients after the insertion of air to examine whether there was an intervening organ. Initially, antibiotics were administered at the discretion of the attending physician. With the introduction of the clinical pathway of PEG in 2009, in principle, 1.5 g of ampicillin-sulbactam was administered twice daily for 2 days: on the day of PEG and the following day. Preoperative antibiotics were used in 181 of 249 patients who underwent PEG. Forty-eight patients were excluded. Twenty patients were unsure if preoperative antibiotics had been used.

Data Collection

Data Collection for Procedure-related Complications

The items listed as procedure-related complications in the medical records were compiled. Regarding data on infectious diseases and diagnoses of pneumonia or fistula infection were collected. Patients who had a high fever or high inflammatory reaction after the procedure and whose physicians used antibiotics for 4 more days were considered to have an infection. Patients without a clear focus of infection on imaging findings or clinical signs were described as having an unknown source. First, the occurrence of complications according to the method (i.e., pull or modified introducer method) was examined. Next, the frequency of infections with and without preoperative antibiotics was examined.

Factors Affecting the Survival Rate after PEG

Data on the following factors were compiled: sex, age, alanine aminotransferase (IU/L), BUN (mg/dL), C-reactive protein (CRP; mg/dL), hemoglobin (Hb; g/dL), serum albumin (g/dL), history of ischemic heart disease, history of pneumonia, diagnosis of cerebrovascular disease, PEG method (pull method or the modified introducer method), and whether the patient was hospitalized for gastrostomy or underwent PEG while hospitalized for another disease. All data were anonymized before analysis to avoid patient identification.

Statistical Analysis

The χ2 test was used to evaluate differences in complication rates according to the PEG method and preoperative antibiotic use. Survival rates were determined using the Kaplan-Meier method, with differences in the survival rate evaluated using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazard modeling was used to determine the factors affecting the survival rate. All statistical processing was performed using BellCurve for Excel (Social Survey Research Information Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

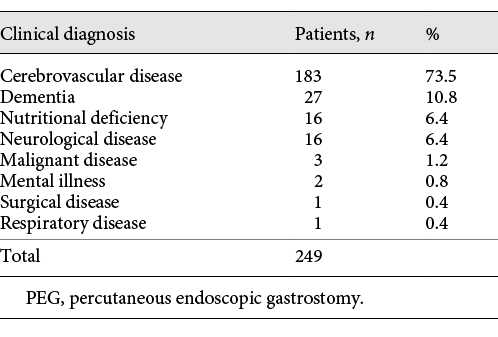

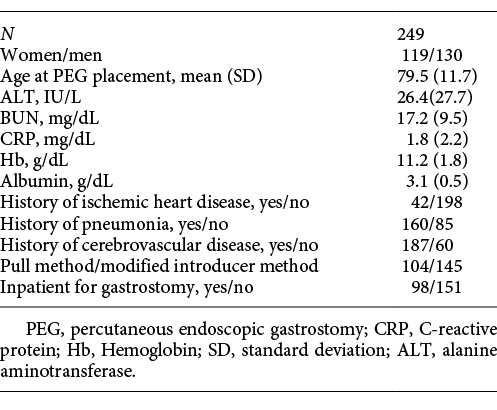

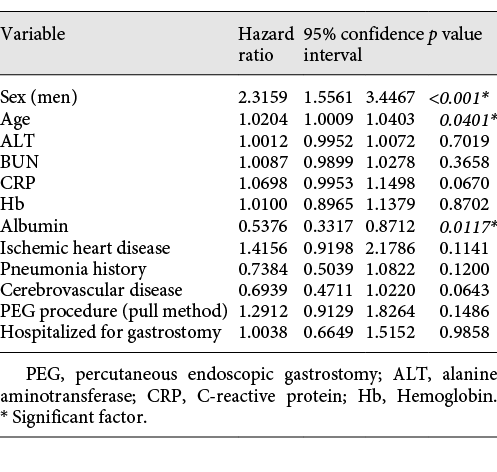

Data on the 249 patients who underwent PEG at Juzenkai Hospital from 2005 to 2017 were reviewed. The most common disease requiring PEG was cerebrovascular disease (183 patients [73.5%]), followed by dementia (27 patients [10.8%]) (Table 1). The baseline characteristics of these 249 cases are summarized in Table 2. The average age at PEG was 79.5 (±11.7) years; 130 patients (52.2%) were men. Forty-two (17.5%) patients had a history of ischemic heart disease, 160 (65.3%) had a history of pneumonia, and 187 (75.7%) had a history of cerebrovascular disease. Furthermore, 98 patients (39.4%) were hospitalized for PEG. Regarding age, the number of patients was the highest among patients in their 80s, followed by those in their 70s (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Number of gastrostomies and sex ratio by age.

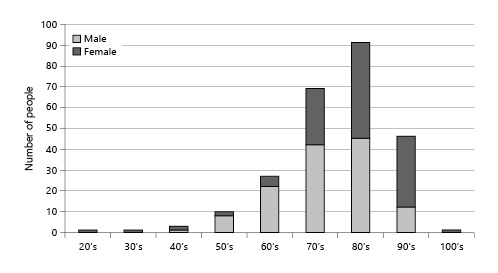

In Juzenkai Hospital, PEG was rarely performed in the acute phase. Therefore, 151 patients (60.6%) who underwent gastrostomy during hospitalization for other acute illnesses had a relatively long average time from hospitalization to gastrostomy, at 47.3 days (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2

Patients who were admitted for purposes other than gastrostomy: number of days from hospitalization to PEG. PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy.

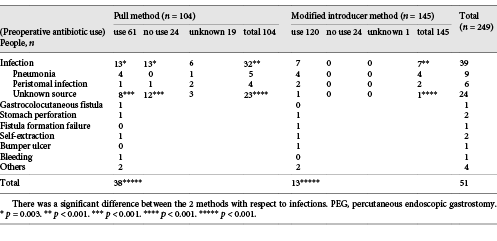

Procedure-Related Complications

Fifty-one (20.5%) procedure-related complications occurred (Table 3). Emergency surgery, including for stomach rupture, was required in 4 cases. Infections accounted for 76.5% (39/51) of complications. Particularly, significantly more infections occurred with the pull method than with the modified introducer method. The use of preoperative antibiotics had a predominant effect on the suppression of infection with the pull method, but not with the modified introducer method. No significant differences were noted between the 2 methods regarding other complications.

In 2009, a gastrocolocutaneous fistula occurred after PEG. Subsequently, both abdominal computed tomography on the day before PEG and abdominal ultrasound on the day of PEG were performed. Since then, gastrocolocutaneous fistula has not occurred.

Survival Rate

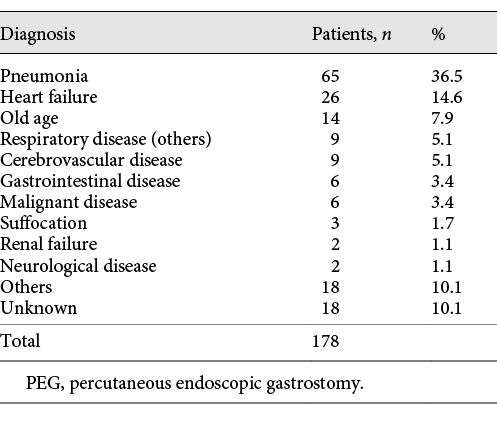

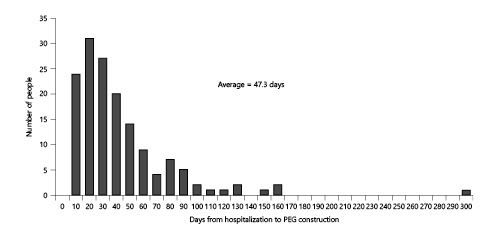

A complete prognosis was achieved in 93.5% of patients. One hundred and seventy-eight deaths occurred in the study period. The most common cause of death was pneumonia, at 65 cases (Table 4). The survival rates in all patients who underwent PEG were analyzed (Fig. 3). The 1-year survival rate was 66.8%, and the median survival time was 678 days. However, 9 patients (3.6%) died within 30 days after gastrostomy.

Fig. 3

Kaplan-Meier survival curve for 249 patients.

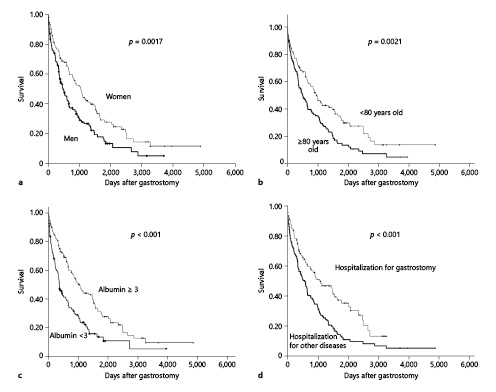

Next, Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated. Selected noteworthy items are shown in Figure 4. Survival rates were significantly higher in women than in men (Fig. 4a), and in patients aged <80 years than in those aged ≥80 years (Fig. 4b). However, patients aged ≥80 years had a 1-year survival rate of 62%, with a good prognosis. The survival rates were compared between patients with preoperative alanine aminotransferase levels ≥30 and <30 IU/L; however, the difference failed to reach significance (p = 0.2945).

Fig. 4

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis comparing patient subgroups: sex (bold line, men; thin line, women) (a), age (bold line, ≥80 years old; thin line, <80 years old) (b), albumin level (bold line, <3 g/dL; thin line, ≥3 g/dL) (c), and reason for hospitalization (bold line, hospitalization for other diseases; thin line, hospitalization for gastrostomy) (d).

The survival rate also did not significantly differ between patients with preoperative BUN ≥20 mg/dL and BUN <20 mg/dL (p value = 0.8778). Patients with preoperative CRP ≥1 mg/dL had significantly worse survival than did those with preoperative CRP <1 mg/dL (p = 0.0203). Patients with Hb <11 g/dL tended to have a significantly poorer prognosis than did those with Hb ≥11 g/dL (p = 0.0342). Patients with preoperative albumin ≥3.0 g/dL had significantly better survival than did those with preoperative albumin <3.0 g/dL (Fig. 4c).

The presence or absence of ischemic heart disease (p = 0.0747) and a history of pneumonia did not significantly affect survival (p = 0.5216). Patients with cerebrovascular disease had significantly better survival than did those without a diagnosis of cerebrovascular disease (p < 0.001). Patients who underwent gastrostomy with the pull method and the modified introducer method had similar survival rates (p = 0.5478). Patients who were hospitalized for the purpose of PEG had a significantly higher survival rate than did patients who underwent PEG during hospitalization for another disease (Fig. 4d).

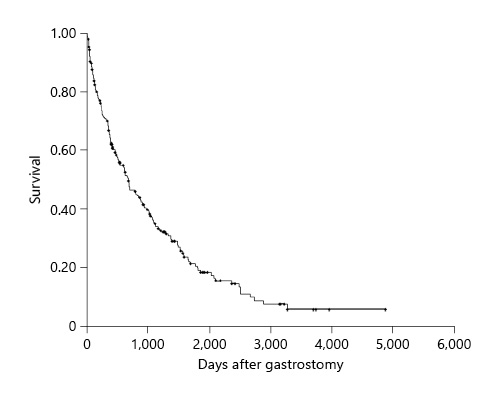

Finally, multivariate analysis was used to determine the factors affecting survival among the items subjected to univariate analysis. Age, sex, and preoperative albumin values were identified as significant factors affecting survival (Table 5).

Discussion/Conclusion

Procedure-related complications occurred frequently between 2005 and 2011. The majority of complications were infections. In many of these patients, the cause of the infection, such as pneumonia or fistula infection was unclear, and most improved with short-term antibiotic treatment. The reason for the decrease in complications of infectious diseases since 2011 was considered to be the change from the pull method to the modified introduction method. Preoperative use of antibiotics significantly reduced the infection rate with the pull method, but had no significant impact with the modified introducer method (Table 3). On the other hand, in 7 cases of PEG with the pull method after gastropexy, no infection was found, and it has been suggested that gastropexy may influence infection []. Efforts were made to reduce complications, and the number of complications subsequently decreased. Additionally, no direct death from gastrostomy was experienced.

In this study, the 1-year survival rate after PEG was 66.8%, and the median survival time was 678 days. In the USA and Europe, several studies conducted since 1990 reported an extremely poor prognosis for PEG [-]. It has been suggested that the reasons for the poor prognosis in these reports were the steep increase in the number of PEGs performed over a short time, and an increase in the number of PEGs performed for diseases for which there was no supporting evidence [, ]. Moreover, many studies have shown that PEG in patients with dementia does not improve their survival or quality of life [, -].

Academic societies, such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN), American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN), and American Geriatrics Society (AGS), do not recommend tube feeding, such as PEG, for patients with dementia, especially severe dementia [-]. The majority of reports and reviews cited in the aforementioned guidelines of NICE, ESPEN, ASPEN, and AGS were from the USA and Europe [, , , -, -], and the prognosis of PEG in these reports was poor. Most of these reports and reviews had a 1-year survival rate of <50% after PEG construction, with many reports in the 20–40% range. In contrast, many Japanese studies, including the study by Suzuki et al. [], showed a good prognosis for PEG [, -]. In these reports, the 1-year survival rate after PEG was in the range of 50–70%, especially around 60%. The present study confirms the findings of these Japanese studies.

In the United States and Europe, PEG is not performed until the patient is significantly nutritionally deficient []. Further, the decision to perform PEG is usually made during hospitalization for acute illness, and gastrostomy is often performed in the acute phase of the disease [, ]. It has been reported that PEG in the acute phase of disease affects survival [, , , , ]. At Juzenkai Hospital, PEG is not performed (as much as possible) in the acute phase of many illnesses. PEG is performed when the patient’s condition has improved, and oral intake has been determined to be impossible (Fig. 2). For patients with acute cerebrovascular disease, nutrition is first improved nasally before transference to a recovery rehabilitation hospital for rehabilitation, including swallowing training. If oral ingestion is still difficult, the patient will return to the hospital for gastrostomy. In this study, patients who were hospitalized for gastrostomy had a better prognosis than did patients who underwent PEG during hospitalization for other diseases (Fig. 4d).

Several studies have detailed the patient factors related to survival after PEG. These factors include age, sex, BMI, low preoperative serum albumin levels, high serum CRP levels, cancer, Charlson comorbidity score, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, renal failure, and heart disease [, , , , -]. In the present study, age, sex, and preoperative albumin level were also identified as factors affecting survival. Further, the presence or absence of dementia is reportedly not related to the prognosis after PEG [, , -].

Regarding indications for PEG, not only the survival rate, but also ethical aspects, and the wishes of the patient and his/her family should be prioritized. Moreover, data specifically pertaining to the patient’s home country or region should be used when explaining the prognosis to patients and their families. The technology of PEG is continuously evolving. Advances in PEG devices reduced the number of procedure-related complications in this study. The use of a button-type gastrostomy tube has almost eliminated the need for patient restraint to prevent self-extraction. The use of semisolid preparations can reduce the risk of aspiration pneumonia. Moreover, nutrients can be injected within a short time, thus minimizing patient restraint and reducing the risk of pressure sores [, ].

A limitation of this study is its retrospective observational design. However, for ethical reasons, randomized prospective studies examining the benefits of gastrostomy are not available. Moreover, this study was conducted in a single center, with a relatively small number of patients; however, the patients were discharged to >80 hospitals and facilities in the city after admittance to our hospital. Therefore, these data are considered to represent the current state of PEG in Nagasaki City and Japan.

Conclusion

The present study results suggest that, due to changes in the PEG insertion method and other factors, PEG has become a safer treatment method. Moreover, patients receiving nutrition with PEG showed good survival rates. The evidence from Japan, including this study, should be widely recognized, enabling more patients to benefit from PEG.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our deep appreciation to the people from the facilities, clinics, and hospitals who took part in the study. Further, we sincerely thank Ms. Yukie Tsujimoto for her support.

Statement of Ethics

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of Juzenkai Hospital (J2020-1). Instead of obtaining informed consent from each patient, notices about the design of the study and other information were posted in public spaces in the hospital.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

No author received any funding related to this study.

Author Contributions

Fumihiro Mawatari designed the study, was involved in patient management, performed gastrostomy, and drafted the manuscript. Hisamitsu Miyaaki and Kazuhiko Nakao provided guidance on planning this research, the research methods, analytical methods, and writing of the article. Tetsuhiko Arima was involved in patient management, performed gastrostomy, and analyzed the study data. In particular, he contributed to the evaluation of procedure-related complication measures. Hiroyuki Ito, Kei Matsuki, Sachiko Fukuda, Yoshiko Kita, Aiko Fukahori, and Yoshito Ikematsu were involved in patient management, performed gastrostomy, and analyzed the study data. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Gauderer MW, Ponsky JL, Izant RJ Jr. Gastrostomy without laparotomy: a percutaneous endoscopic technique. J Pediatr Surg. 1980 Dec;15(6):872–5.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3468(80)80296-x.

- 2. Ponsky JL, Gauderer MW. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: a nonoperative technique for feeding gastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1981 Feb;27(1):9–11.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0016-5107(81)73133-x.

- 3. Rabeneck L, Wray NP, Petersen NJ. Long-term outcomes of patients receiving percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes. J Gen Intern Med. 1996 May;11(5):287–93.http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02598270.

- 4. Grant MD, Rudberg MA, Brody JA. Gastrostomy placement and mortality among hospitalized medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 1998 Jun;279(24):1973–6.http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.279.24.1973.

- 5. Wolfsen HC, Kozarek RA, Ball TJ, Patterson DJ, Botoman VA, Ryan JA. Long-term survival in patients undergoing percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and jejunostomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990 Sep;85(9):1120–2..

- 6. Fay DE, Poplausky M, Gruber M, Lance P. Long-term enteral feeding: a retrospective comparison of delivery via percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and nasoenteric tubes. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991 Nov;86(11):1604–9..

- 7. Taylor CA, Larson DE, Ballard DJ, Bergstrom LR, Silverstein MD, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Predictors of outcome after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: a community-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 1992 Nov;67(11):1042–9.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61118-5.

- 8. Finocchiaro C, Galletti R, Rovera G, Ferrari A, Todros L, Vuolo A, et al. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: a long-term follow-up. Nutrition. 1997 Jun;13(6):520–3.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0899-9007(97)00030-0.

- 9. Löser C, Wolters S, Fölsch UR. Enteral long-term nutrition via percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) in 210 patients: a four-year prospective study. Dig Dis Sci. 1998 Nov;43(11):2549–57..

- 10. Sanders DS, Carter MJ, D'Silva J, James G, Bolton RP, Bardhan KD. Survival analysis in percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy feeding: a worse outcome in patients with dementia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000 Jun;95(6):1472–5.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02079.x.

- 11. Suzuki Y, Tamez S, Murakami A, Taira A, Mizuhara A, Horiuchi A, et al. Survival of geriatric patients after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in Japan. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 Oct;16(40):5084–91.http://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i40.5084.

- 12. Iijima S, Aida N, Ito H, Endo H, Ohrui T, et alJapanese Geriatric Society Ethics Committee. Position statement from the Japan Geriatrics Society 2012: end-of-life care for the elderly. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014 Oct;14(4):735–9.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12322.

- 13. Nishiguchi Y. What happened after PEG bashing? [in Japanese]. J JSPEN. 2016 Dec;31(6):1225–8..

- 14. Komiya K, Usagawa Y, Kadota JI, Ikegami N. Decreasing use of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube feeding in Japan. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018 Jul;66(7):1388–91.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15386.

- 15.

- 16. Funada M. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: a new gastropexy method [in Japanese]. Gastroenterol Endosc. 1991;33:2681..

- 17. Inoue N, Nagaike K, Ishihara S, Nakamura M, Kuroshima T, Yoshiwara W. A new PEG technique “Direct Method” and fistula infection [in Japanese with English abstract]. Home Health Care Endosc Ther Qual Life. 2005;9:79–83..

- 18. Okumura N, Tsuji N, Ozaki N, Matsumoto N, Takaba T, Kawasaki M, et al. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy with Funada-style gastropexy greatly reduces the risk of peristomal infection. Gastroenterol Rep. 2015 Feb;3(1):69–74.http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gastro/gou086.

- 19. Janes SE, Price CS, Khan S. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: 30-day mortality trends and risk factors. J Postgrad Med. 2005 Jan–Mar;51(1):23–9; discussion 28–9.

- 20. Leontiadis GI, Moschos J, Cowper T, Kadis S. Mortality of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in the UK. J Postgrad Med. 2005 Apr–Jun;51(2):152..

- 21. Meier DE, Ahronheim JC, Morris J, Baskin-Lyons S, Morrison RS. High short-term mortality in hospitalized patients with advanced dementia: lack of benefit of tube feeding. Arch Intern Med. 2001 Feb;161(4):594–9.http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinte.161.4.594.

- 22. Finucane TE, Christmas C, Travis K. Tube feeding in patients with advanced dementia: a review of the evidence. JAMA. 1999 Oct;282(14):1365–70.http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.14.1365.

- 23. Sampson EL, Candy B, Jones L. Enteral tube feeding for older people with advanced dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Apr;2009(2):CD007209.

- 24. Murphy LM, Lipman TO. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy does not prolong survival in patients with dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2003 Jun;163(11):1351–3.http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinte.163.11.1351.

- 25.

- 26. Volkert D, Chourdakis M, Faxen-Irving G, Frühwald T, Landi F, Suominen MH, et al. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in dementia. Clin Nutr. 2015 Dec;34(6):1052–73.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2015.09.004.

- 27. Barrocas A, Geppert C, Durfee SM, Maillet JO, Monturo C, et alA.S.P.E.N. Ethics Position Paper Task Force. A.S.P.E.N. ethics position paper. Nutr Clin Pract. 2010 Dec;25(6):672–9.http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0884533610385429.

- 28.

- 29. Abuksis G, Mor M, Segal N, Shemesh I, Plout S, Sulkes J, et al. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: high mortality rates in hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000 Jan;95(1):128–32.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01672.x.

- 30. Kuo S, Rhodes RL, Mitchell SL, Mor V, Teno JM. Natural history of feeding-tube use in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009 May;10(4):264–70.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2008.10.010.

- 31. Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Lipsitz LA. The risk factors and impact on survival of feeding tube placement in nursing home residents with severe cognitive impairment. Arch Intern Med. 1997 Feb;157(3):327–32.http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1997.00440240091014.

- 32. Callahan CM, Haag KM, Weinberger M, Tierney WM, Buchanan NN, Stump TE, et al. Outcomes of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy among older adults in a community setting. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000 Sep;48(9):1048–54.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04779.x.

- 33. Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Mitchell SL, Kuo S, Rhodes RL, Bynum JP, et al. Does feeding tube insertion and its timing improve survival?J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012 Oct;60(10):1918–21.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04148.x.

- 34. Jaul E, Singer P, Calderon-Margalit R. Tube feeding in the demented elderly with severe disabilities. Isr Med Assoc J. 2006 Dec;8(12):870–4..

- 35. Alvarez-Fernández B, García-Ordoñez MA, Martínez-Manzanares C, Gómez-Huelgas R. Survival of a cohort of elderly patients with advanced dementia: nasogastric tube feeding as a risk factor for mortality. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005 Apr;20(4):363–70.http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/gps.1299.

- 36. Kumagai R, Kubokura M, Sano A, Shinomiya M, Ohta S, Ishibiki Y, et al. Clinical evaluation of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube feeding in Japanese patients with dementia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012 Aug;66(5):418–22.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2012.02378.x.

- 37. Onishi J, Masuda Y, Kuzuya M, Ichikawa M, Hashizume M, Iguchi A. [Long-term prognosis and satisfaction after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in a general hospital]. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 2002 Nov;39(6):639–42.http://dx.doi.org/10.3143/geriatrics.39.639.

- 38. Matsubara J, Fujita Y, Hashimoto A, Niinami C, Itoh T, Maruyama M. Clinical analysis of outcomes and prognosis related to percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy among the elderly [in Japanese]. Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2005 Mar;102(3):303–10..

- 39. Kanzaki N, Ishii S, Suzuki M, Ono Y, Zenda S. Long-term prognosis and actual circumstances after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy at our hospital [in Japanese]. Fukushima Med J. 2012;62:152–7..

- 40. Arora G, Rockey D, Gupta S. High in-hospital mortality after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: results of a nationwide population-based study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Nov;11(11):1437–e3.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2013.04.011.

- 41. Mendiratta P, Tilford JM, Prodhan P, Curseen K, Azhar G, Wei JY. Trends in percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy placement in the elderly from 1993 to 2003. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012 Dec;27(8):609–13.http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1533317512460563.

- 42. Elia M, Russell CA, Stratton RJ, Holden CE, Micklewright A, Barton A, et al. Trends in artificial nutritional support in the UK during 1996–2000. A Report by the British Artificial Nutrition Survey (BANS). Maidenhead: British Association of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition; 2001.

- 43. Niv Y, Abuksis G. Indications for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy insertion: ethical aspects. Dig Dis. 2002 Jan;20(3–4):253–6.http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000067676.

- 44. Blomberg J, Lagergren P, Martin L, Mattsson F, Lagergren J. Albumin and C-reactive protein levels predict short-term mortality after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in a prospective cohort study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011 Jan;73(1):29–36.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2010.09.012.

- 45. Lang A, Bardan E, Chowers Y, Sakhnini E, Fidder HH, Bar-Meir S, et al. Risk factors for mortality in patients undergoing percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Endoscopy. 2004 Jun;36(6):522–6.http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-2004-814400.

- 46. Zopf Y, Maiss J, Konturek P, Rabe C, Hahn EG, Schwab D. Predictive factors of mortality after PEG insertion: guidance for clinical practice. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011 Jan;35(1):50–5.http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0148607110376197.

- 47. Smith BM, Perring P, Engoren M, Sferra JJ. Hospital and long-term outcome after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Surg Endosc. 2008 Jan;22(1):74–80.http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00464-007-9372-z.

- 48. Higaki F, Yokota O, Ohishi M. Factors predictive of survival after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in the elderly: is dementia really a risk factor?Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 Apr;103(4):1011–7.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01719.x.

- 49. Gaines DI, Durkalski V, Patel A, DeLegge MH. Dementia and cognitive impairment are not associated with earlier mortality after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2009 Jan–Feb;33(1):62–6.http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0148607108321709.

- 50. Smoliner C, Volkert D, Wittrich A, Sieber CC, Wirth R. Basic geriatric assessment does not predict in-hospital mortality after PEG placement. BMC Geriatr. 2012 Sep;12:52.http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-12-52.

- 51. Kanie J, Suzuki Y, Iguchi A, Akatsu H, Yamamoto T, Shimokata H. Prevention of gastroesophageal reflux using an application of half-solid nutrients in patients with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy feeding. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004 Mar;52(3):466–7.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52125_1.x.

- 52. Toh Yoon EW, Yoneda K, Nishihara K. Semi-solid feeds may reduce the risk of aspiration pneumonia and shorten postoperative length of stay after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). Endosc Int Open. 2016 Dec;4(12):E1247–51.http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-117218.