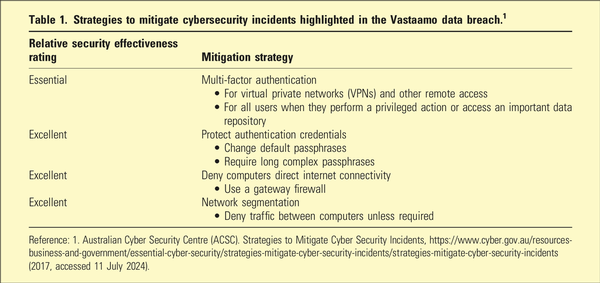

Patient confidentiality is central to mental healthcare. This ethical obligation is challenging within web-linked electronic health records in modern health information systems. However, there are strategies that mitigate cybersecurity incidents, which need to be adopted in public and private sector practice (Table 1). If there are gaps in cybersecurity, data breaches are more likely to occur with implications for patients, IT system administrators and psychiatrists. We examine the lessons for good standards of data security practice in psychiatry from a case study of a serious electronic health record data breach of highly confidential patient information from a large private psychotherapy service.

This case study is based on media reporting and analysis (Ralston at Wired, Rimpalainen and Rautio at Yle, and Tidy at the BBC)– in a criminal case with the largest number of victims in Finland to date, the Vastaamo psychotherapy service electronic health record data breach. In 2024, the hacker who accessed the electronic health record database of the Vastaamo private psychotherapy provider was sentenced to jail for 6 years and 3 months for 30,000 crimes (one for each victim), including charges of aggravated data breach, attempted aggravated blackmail, and aggravated dissemination of information infringing private life. The reason we have drawn upon the media analysis and reporting is that it presents details that are useful to discuss, and that, to date, there remains limited peer-reviewed publication on the topic. (We could not access the original legal proceedings of the court case.) We provide an analysis of the implications for individual and organisational mental healthcare providers, including psychiatrists, referring to locally relevant advice on cybersecurity from the Australian Digital Health Agency and the Australian Cyber Security Centre.,

The Vastaamo private psychotherapy provider – Technical history and aspects

Vastaamo was established by CEO Ville Tapio in 2009 with seed-funding from the Finnish Innovation Fund, a governmental foundation that invests in social goods, and funding from Tapio’s family. While initially developed as a telehealth service, Vastaamo expanded to in-person therapy, facilitated by software for billing and health records, as well as physical locations that soon recruited therapists to provide care through the platform.

Vastaamo designed a bespoke electronic health record (EHR), reported to be a browser-based system storing data on a MySQL server, rather than using a validated industry-standard system. However, this EHR was reported as failing to anonymise or encrypt the patient record data in transit or at rest in the database., Therefore, security defaulted to firewalls protecting the server and server’s password-based login. In Vastaamo’s case, there is no reporting of two-factor authentication of logins, and, as will be seen later, there were problems with both the firewalls and logins.

The Australian Digital Health Agency (ADHA) recommends layers of protection for data security due to the requirement for privacy of personal data under Commonwealth legislation through the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner. Logins are recommended to be protected via complex passwords and two-factor authentication., Patient data like any personal data needs to be encrypted to protect data in the database, and when accessed. Anonymisation may not be practicable for EHRs, so the above protections are important.

Finland also has governmental regulations for medical information systems (including EHRs), and in 2014, there were two classes specified. A higher standard, Class A, was applied to systems that interfaced with the Finnish equivalent of the Australian electronic MyHealthRecord, Kanta – this standard required strict security and interoperability with the governmental system. Vastaamo applied for certification as a Class B system in 2017, intended for small organisations and with self-certification of meeting requirements, with the understanding that it would need to adopt Class A within several years under the 2014 law. Vastaamo continued to expand its network of providers, sites and data held under the less demanding Class B regulations. Cybersecurity investigators found that Vastaamo’s data protection and security were unsatisfactory in 2017 and 2020 reviews.

The ADHA provides a list of questions to guide healthcare providers in sourcing secure IT products, including EHRs. Among these items are how an IT service provider both monitors and responds to data breaches. Concerningly, Vastaamo’s IT system administrator and data protection officers admitted to the Vastaamo CEO that they had been arrested as part of a security breach of the Finnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovation, where it was reported the administrators had downloaded an entire database, but were not convicted of a crime. It transpired that there were perhaps at least two data breaches at Vastaamo in 2018 and 2019 that were unreported, prior to the 2020 data breach (more on this later)., Tapio stated that he believed the system IT administrators had enabled remote access to the database server by disabling the firewalls without using the protection of a VPN., If these events happened as stated by Tapio, there would be only the system IT administrator’s login protecting the database and external access, substantially weakening security against recommended standards for private, including healthcare data.,

Finnish media reports that we have had translated indicate there were highly unsatisfactory practices for sharing of passwords of low complexity, and, in some cases, no password protection at all. This is relevant as the healthcare provider therapists used such passwords for remote access, and as such, constituted a very substantial deficiency of cybersecurity at the user end.

The hacker first contacted the Vastaamo CEO on 28th September 2020 with a ransom demand for 40 bitcoin (c. US$400–500k). The hacker contacted a Finnish reporter as well as posting emails to a public discussion board. They then proceeded to a discussion forum on the dark web and claimed they would leak 100 records a day until the ransom was received. There were a series of leaks of records from 21 October 2020, and then two events in succession, the entire psychotherapy record database was leaked on 22nd October on the dark web, and the hacker used personal contact details to extort individual patients via email and/or SMS., Eventually, Vastaamo was liquidated on 28 January 2021. There were some Finnish governmental responses, such as allowance to change social, security numbers, analogous to the Australian Commonwealth approach to Medicare numbers for the Medibank data breach.

Cybersecurity practice lessons from Vastaamo

The learning from the Vastaamo data breach is that governance and ongoing effective cybersecurity practices are essential, and especially so for sensitive patient data in healthcare information systems. There were failures of governance and cybersecurity practice at multiple levels contributing to the tragic outcomes.

As a healthcare provider using electronic health records, Vastaamo did not appear to have designed the IT platform with industry standard methods for data security and privacy, including a lack of encryption of sensitive data in the database and for remote access or transit.,, The regulation and use of passwords was very unsatisfactory. This reflects governance shortfalls in the performance of the private psychotherapy organisation.

The staff that Vastaamo employed as System Administrators/Data Protection Officers have been alleged by the CEO, and reported in the media, as having been charged with data breach offences, but not convicted. Perhaps such staff were not suitable for roles in safeguarding sensitive data.

The Vastaamo CEO had speculated that the protections for the patient record database server were possibly weakened by staff of the company including loss of the firewalls and then leaving minimal protection of the server login.,

Recommended best practice for cybersecurity, as advised in detail by the ADHA, should help healthcare providers address the structural weaknesses demonstrated in the Vastaamo case, such as implementing encryption of data within the database at rest and in transit, optimal password usage and multifactor authentication.

The other important issue relates to regulations that enforce standards, and it is clear that in the Vastaamo case, self-regulation as a Finnish Class B health information system was disastrous. Rigorous standards are required for data privacy and security. Australia has federal government mandated privacy obligations for organisations holding personal data as of 2022. However, these do not have the detail and range of protections such as the Health Insurance Privacy and Portability Act in the US, which might be considered a more specific and fit-for-purpose model for regulation of healthcare data privacy.

Mental healthcare consequences of the Vastaamo data breach

There were substantial reported harms ranging from distress to tragic suicides because of the leaking of the personal psychotherapy records by the hacker. Further legal actions are being taken by victims and families affected by the data breach. Though seemingly unusual in healthcare, the direct extortion of patients parallels other attempts to leak sensitive data, such as in the Australian Medibank data breach, where the private health insurance records for people with mental health and substance use disorders was posted online to extort the insurer.

For Vastaamo patients, detailed psychotherapy records made by therapists to assist in the provision of therapy, in common with other therapy and psychiatric health records, contained particularly private and sensitive information. The threatened release of such information caused significant levels of distress and vulnerability for patients with mental illnesses, and carers and relatives, and as reported, may occasion more harms.

Lessons from the mental health impacts of Vastaamo

With burgeoning data breaches such as Vastaamo, and those in various healthcare information systems in Australia such as Australian Clinical Labs and Medibank,, it has been recommended to consider minimising potentially sensitive information in psychiatric EHRs because it is inevitable that the data will be breached. An independent systematic review of healthcare information system cybersecurity also concluded that data breaches of EHRs would inevitably occur. Therefore, it has been suggested that sensitive information, such as detailed psychotherapy notes, should be stored offline, with a summary avoiding sensitive details included in the EHR.

Clinicians should familiarise themselves with the Australian Privacy Principles referred to in the Commonwealth Privacy Act 1988 as they apply to the handling and storage of personal, including health information. This encompasses the use of pseudonyms, destruction and deidentification of data that is no longer required. The New Zealand Privacy Act 2020 contains similar privacy principles.

Further, detailed, evidence-based plans for supporting patients and healthcare workers after data breaches should be enacted by healthcare providers, as described in a recent paper.

Conclusions

As a case study, the Finnish Vastaamo psychotherapy data breach highlights the tragically personal consequences of neglect of good governance of health information systems, especially in regard to cybersecurity in mental healthcare settings. The lessons are that regulation, governance and best practices are all necessary to ensure the security of sensitive mental health records. Specific security strategies to mitigate cybersecurity incidents highlighted in this case study are summarised in Table 1. In Australia, strengthening health data privacy regulation, and potentially credentialling of healthcare providers for data security, may assist in enforcing appropriate standards of practice in a manner analogous to the role of health practitioner practice regulation by AHPRA. Risks can be further mitigated, but not completely eliminated, by minimisation and careful consideration of what essential data are entered into such records, avoiding the inclusion of sensitive material within online databases.

Authorship All authors have satisfied: Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work; drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Disclosure The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors declare that JCLL, SA, TB, PAM, SK and SR are editorial team members for the journal – they were not involved in the independent peer review process.

Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. ACSC. Strategies to mitigate cyber security incidents. Available at: https://www.cyber.gov.au/resources-business-and-government/essential-cyber-security/strategies-mitigate-cyber-security-incidents/strategies-mitigate-cyber-security-incidents (2017, accessed 11 July 2024).

- 2. Ralston W. They told their therapists everything: hackers leaked it all. Available at: https://www.wired.com/story/vastaamo-psychotherapy-patients-hack-data-breach/ (2021, accessed 7 June 2024).

- 3. Rimpilainen T. In 2012, a password for workstations “ammi70” was created at the Malmi office in Vastaamo – then it was used everywhere for years. Available at: https://yle.fi/a/74-20020562 (2023, accessed 10 July 2024).

- 4. Rautio M. Prosecutor calls for imprisonment: ex-CEO of Vastaamo knew of company security deficiencies – concealed a data breach of spring 2019. Available at: https://yle.fi/a/74-20020506 (2023, accessed 10 July 2024).

- 5. Tidy J. From teenage cyber-thug to Europe’s most wanted. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cyxe9g4zlgpo (2024, accessed 6 May 2024).

- 6. ADHA. Cybersecurity for healthcare providers. Available at: https://www.digitalhealth.gov.au/healthcare-providers/cyber-security (2024, accessed 10 July 2024).

- 7. ADHA. Information security guide for small healthcare businesses. Available at: https://www.digitalhealth.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-11/Information_security_guide_for_small_healthcare_businesses.pdf (2018, accessed 10 July 2024).

- 8. ADHA. Selecting secure IT products and services - questions to ask your IT vendors. Available at: https://www.digitalhealth.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-11/Selecting_secure_IT_products_and_services-Questions_to_ask_your_IT_vendors.pdf (2020, accessed 10 July 2024).

- 9. Parliament_of_Australia. Privacy legislation amendment (enforcement and other measures) bill 2022. Available at: https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation/bd/bd2223a/23bd030 (2022, accessed 8 May 2024).

- 10. US_Department_of_Health_and_Human_Services. What does the HIPAA Privacy Rule do? Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-individuals/faq/187/what-does-the-hipaa-privacy-rule-do/index.html (2023, accessed 11 October 2023).

- 11. Foster J, Williams JJ. Medibank hackers are now releasing stolen data on the dark web. In If you’re affected, here’s what you need to know 2022. Available at: https://theconversation.com/medibank-hackers-are-now-releasing-stolen-data-on-the-dark-web-if-youre-affected-heres-what-you-need-to-know-194340 (accessed 11 October 2023).

- 12. Looi JC, Looi RC, Maguire PA, et al. Psychiatric electronic health records in the era of data breaches - what are the ramifications for patients, psychiatrists and healthcare systems? Australas Psychiatr 2024; 32: 121–124. DOI: .

- 13. OIAC. AIC v Australian clinical Labs limited concise statement. Available at: https://www.oaic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/112526/AIC-v-Australian-Clinical-Labs-Limited-concise-statement.pdf (2023, accessed 1 December 2023).

- 14. Terzon E, Yang S. Medibank says all customers' personal data compromised by cyber attack. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-10-26/medibank-hack-criminals-access-hack-data/101578438 (2022, accessed 25 September 2023).

- 15. Offner KL, Sitnikova E, Joiner K, et al. Towards understanding cybersecurity capability in Australian healthcare organisations: a systematic review of recent trends, threats and mitigation. Intell Natl Secur 2020; 35: 556–585. DOI: .

- 16. OIAC. The privacy Act. https://www.oaic.gov.au/privacy/privacy-legislation/the-privacy-act (2024, accessed 17 July 2024).

- 17. Privacy_Commissioner. Privacy Act 2020 and the privacy principles. Available at: https://www.privacy.org.nz/privacy-act-2020/privacy-principles/ (2020, accessed 17 July 2024).

- 18. Looi JC, Allison S, Bastiampillai T, et al. Healthcare provider data breaches - framework for crisis communication and support of patients and healthcare workers in mental healthcare. Australas Psychiatr 2024; 3: 10398562241261818. DOI: .