Linked Article: Hughes and Thompson Br J Dermatol 2024; 191:9–10.

What is already known about this topic?

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a heterogeneous disease, with the term ‘flare’ used ubiquitously to describe increased disease activity.

Several definitions of flare have been proposed but with limited patient involvement and input.

The patient perspective of the meaning of ‘flare’ has not been adequately explored in AD.

What does this study add?

This study elucidates a framework of the constructs that define an AD flare from the patient perspective.

Concepts identified by patients as important to a definition of flare were changes from patient’s baseline/patient’s normal, mental/emotional/social consequences, physical changes in skin, attention needed/all-consuming focus, itch–scratch–burn cycle and control/loss of control/quality of life.

Participants shared concerns that published definitions of AD flares are not entirely relatable.

What are the clinical implications of this work?

The results provide a broader appreciation of the complexity and diversity of AD flare based on patients’ lived experiences.

Understanding the definition of flare from the patient perspective will help support care and treatment conversations, as well as future assessments of treatment efficacy and patient-reported outcomes in clinical research.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic condition of a relapsing and remitting nature, characterized by inflamed, itchy skin that ‘flares’ and has profound and wide-ranging impacts on people’s quality of life (QoL). AD is a heterogeneous disease that can present differently from one individual to the next and even within individuals over a course of a lifetime. AD is estimated to affect 10.7% of children in the USA, of which one-third have moderate-to-severe disease, and 7.3% of adults in the USA, of which nearly 40% have moderate-to-severe disease.,

The term ‘flare’ is commonly used in many conditions, such as asthma, rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, to describe increased disease activity or symptoms. Flare is used by patients and healthcare providers in the care setting to describe the patient’s lived experience of signs and symptoms and discuss treatment options. AD clinical research studies often cite flares as a measure of disease activity and to demonstrate efficacy of treatments, yet the term ‘flare’ is defined differently across studies. Several definitions have been proposed by the medical research community and clinical task forces; however, these have included minimal input from patients. Furthermore, the concepts that are important to include in a definition of flare from the patient perspective have not been well defined. As such, there is no consensus on the definition of flare for AD.

Patient engagement in chronic disease research is crucial because it provides relevancy, a key perspective of stakeholders and a broader understanding of the range of symptoms and life implications of chronic conditions. The absence of a definition of flare developed with patient involvement is a gap in our understanding of the lived experience of AD, and its implications for care and treatment. The aims of this qualitative study were to characterize how adults with AD define ‘flare’ and determine the concepts important (and not important) to include in a definition of AD flare from the patient perspective.

Materials and methods

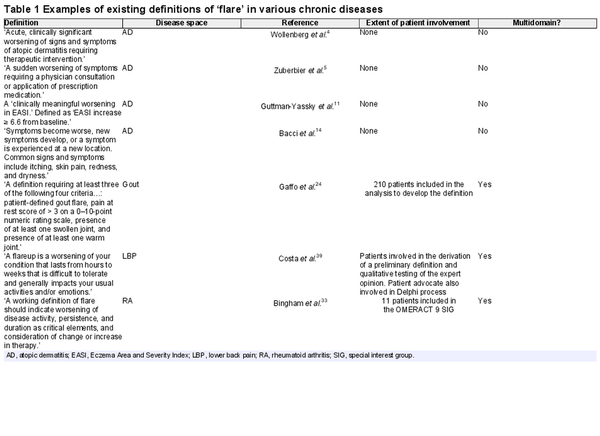

A literature review was conducted to understand how the term ‘flare’ is used within AD and across other chronic inflammatory diseases (i.e. atopic dermatitis; eczema broadly defined; cutaneous lupus erythematosus; juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus; lupus broadly defined; chronic rhinosinusitis; gout; osteoarthritis; rheumatoid arthritis; hidradenitis suppurativa; asthma; low back pain; musculoskeletal conditions broadly defined; and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) and to identify whether a definition exists, the extent of patient involvement in creating the definition and whether the definition was multidomain/multidimensional. Example definitions identified from the literature review are shown in Table 1. Literature review findings were used to inform areas to explore in focus group discussions.

Study design

This qualitative study was designed using a constructivist grounded theory approach. Constructivist grounded theory is a research method that focuses on generating new theories through inductive analysis of the data gathered from participants rather than from pre-existing theoretical frameworks. This approach allowed us to understand the phenomenon of ‘flare’ and construct theories through participants’ experiences, using iterative data collection and analysis. A focus group approach was chosen so that patients with AD could, in their own words, describe their flares, what it means to be in a flare, what it means to be out of or end a flare and to capture their reactions to existing definitions of flare. Focus groups were chosen over individual interviews to allow for discussion between patients and the evolution of concepts within the group. Virtual focus groups were scheduled for 90 min and conducted virtually using Zoom version 5.10.7 (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA, USA). Sessions were recorded and automatically transcribed using Rev transcription service version 2022-05-19 (https://www.rev.com).

Participant recruitment

Adult US residents diagnosed with AD with a self-reported AD flare in the past 12 months were eligible to participate. Participants were recruited from the National Eczema Association (NEA) Ambassadors programme, a volunteer programme geared towards engaging patients in eczema advocacy, research and community activities, as well as from the NEA’s scholarship recipient list. Patients were recruited from these programmes to select for high engagement and demonstrated contribution to projects. Recruitment included an online screening questionnaire via SurveyMonkey (https://www.surveymonkey.com) which collected basic demographics and AD history to allow for selection of a broad representation of AD lived experience (e.g. personal demographics and disease history). Some potential participants were excluded once we met proportional saturation with certain characteristics, such as sex and race. The researchers aimed for 25–30 participants in total, a number based on past research experience by the authors at reaching discussion saturation (including unpublished NEA survey conceptualization focus groups). To facilitate discussion and diversity of experiences, no more than eight participants were included in each session.

Data collection

A focus group discussion guide was created based on the literature review and minorly adjusted (prompting and questions further refined for clarity or relevance) in response to what was learned with the initial focus groups (I.J.CT. and K.N.D.). Focus groups were all led by a NEA staff member (I.J.C.T.). Before entering the main discussion, participants were invited to share a 2–3 sentence introduction about themselves, including their name, number of years living with AD, severity of AD and 1–2 aspects about their AD experience.

Participants were asked what the phrase ‘atopic dermatitis flare’ meant to them. Additional prompting from the facilitator included ‘When do you use the word flare?’; ‘Has your view of flare changed over time?’; ‘Can a flare be “unseen”?; ‘How do you deal with a flare?’; and ‘Do you feel differently about defining a flare based on body part (e.g. face vs. toes)?’ Participants were then asked what the first indication is that they are entering a flare. Additional prompting included: ‘Do you get a “premonition” or a “Spidey sense” about when a flare is about to start?’; ‘What indicates that a flare is over?’; and ‘How long does a flare need to last to be considered a flare?’ Participants were next shown some existing definitions of AD flare (Table 1), and asked for their perspectives. Additional prompting included: ‘Do you understand the words or phrases used in the definitions?’; ‘Are the concepts raised the most important regarding a flare?’; and ‘Would you word any of these differently?’ Finally, the participants were asked to share what they would include in a definition if they could create their own. Prompting included: ‘Is what they would include more or less important than what was already shared from existing definitions or by the group?’; ‘Consider frequency and severity of the flare’; and ‘What does ‘flare’ not mean?’

Researcher positionality

I.J.C.T. has > 8 years of professional experience designing and conducting focus groups involving sensitive topics, three of which were with the NEA covering eczema topics specifically. She was known to some of the participants beforehand as a researcher at NEA, and some of the participants were known to each other, having participated previously in NEA research or advocacy activities together. I.J.C.T. ensured any personal thoughts on flare did not find their way into the discussion by following the discussion guide closely and employing standard discussion techniques to prompt or expand on concepts shared by participants without volunteering or reshaping ideas. K.N.D. is a qualitative social scientist and holds a Research Chair in Patient-centred Outcomes and Associate Professorship in Health Services Research at the University of Toronto. She has conducted numerous qualitative studies of patient and family experience in healthcare but had not worked in the area of AD prior to this study.

Data analysis

Two investigators (K.N.D. and K.A.) analysed the transcripts to derive overarching concepts and developed an AD flare concept framework. Following transcription, K.N.D. and K.A. analysed each transcript independently, followed by a consensus meeting to discuss the codes identified and resolve any ambiguities and disagreements. In accordance with descriptive qualitative methods, investigators followed an iterative process of reading the data, deriving codes (labelling meaningful units), re-reading the codes to begin thematic clustering, comparing the data and discussing descriptions of the codes and themes. Codes were then collapsed into subcategories and described as constructs within a developing conceptual framework of ‘flare’, from the perspective of the patients/participants.

In developing the key components of a framework to inform a definition of ‘flare’, the authors specifically looked at the themes that were raised in relation to defining a flare by the participants, ensuring not to include themes from adjacent discussion around treatment and impact of AD. This framing of the results was purposefully separate from the personal experiences or consequences of a flare (i.e. tingling sensation, loss of sleep and ways of treating).

A patient with AD not involved in the focus groups (M.W.) was recruited from the NEA Ambassadors programme as a co-author, to provide the patient perspective.

Results

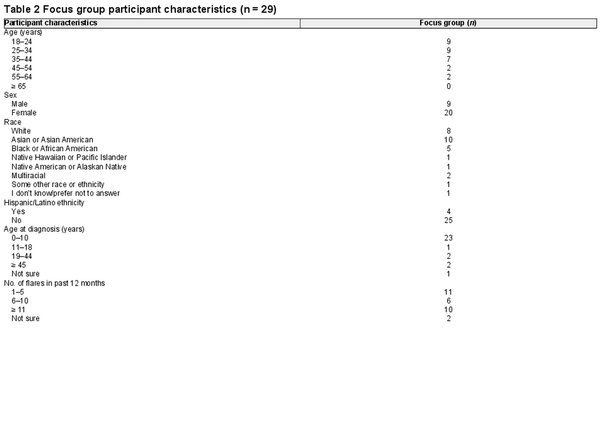

Six 90-min sessions were conducted from 17 May to 3 June 2022, each attended by 3–8 adults with AD for a total of 29 participants (Table 2). Participants were mostly women (69%), Asian or Asian American (35%), aged 18–35 years (62%) and diagnosed with AD in childhood (83%). All participants self-reported moderate or severe AD when their AD was at its worst, but at the time of recruitment participants reported severity from clear to severe.

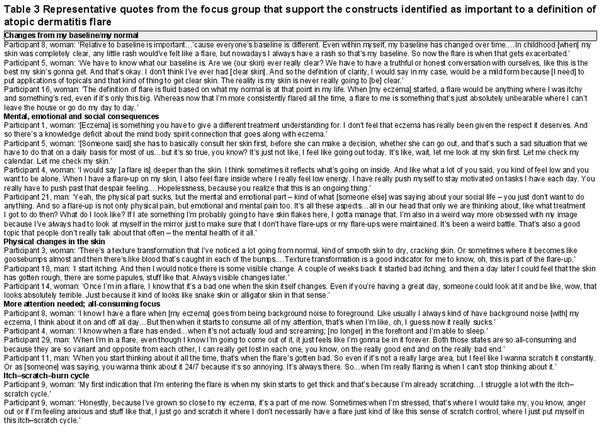

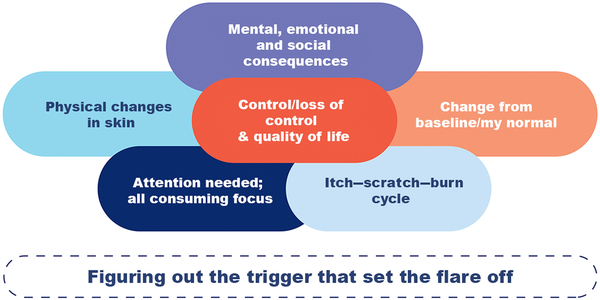

Six key concepts that defined a flare for participants were (i) changes from patient baseline/normal; (ii) mental, emotional and social consequences; (iii) physical changes in skin; (iv) more attention needed/all consuming focus; (v) the itch–scratch–burn cycle; and (vi) control/lack of control and QoL (Figure 1). The theme of figuring out the trigger for a flare, while an accompanying reflection and concern, was not a concept that defined an AD flare. Representative participant quotes are provided in Table 3.

Figure 1

Proposed framework of the constructs that define an atopic dermatitis flare from the patient perspective.

Changes from patient baseline/normal

The concept of change from baseline emphasized the heterogeneity of each patient’s condition, including severity, disease activity location, perception of chronicity and acceptability of their condition. For example, one participant acknowledged that, ‘even within myself, my baseline has changed over time’ and that when they were a child with completely clear skin, ‘any little rash would’ve felt like a flare,’ whereas ‘nowadays, I always have a rash so that’s my baseline’. Another participant emphasized severity and acceptability, saying that when their AD started, ‘a flare would be anything where I was itchy and something’s red, even if it’s only this big’ – while making a small ‘pinch’ gesture. This participant’s baseline evolved to where a flare is ‘something that’s just absolutely unbearable where I can’t leave the house or go do my day to day.’ This person no longer characterized their flare by just signs and symptoms, but by acceptability of the impact of the AD on QoL. Other participants described this change in acceptability (and thus change in their baseline) by recognizing that even with treatments, ‘this is the best my skin’s gonna get – and that’s okay.’

Mental, emotional and social consequences

Participants all agreed that there is a ‘mind–body connection’ with AD that shapes how they experience and view flares. To many participants, flare is not just a physical change in skin, but also involves a change in mental health. ‘A flare is deeper than the skin,’ explained one participant. ‘You kind of feel low and you want to be alone.’ For example, participants reported that AD symptoms may induce feelings of isolation, anxiety or depression, as well as concern with body image. For some participants, these feelings are what set apart a flare from their ‘normal’ condition. Some participants reported that an exacerbation was more likely to be viewed as a flare if it were on a visible part of the body (like the face or hands) as opposed to hidden (like on the torso under a shirt) because of the mental, emotional and social consequences on the patient.

Physical changes in skin

Many participants noted that while itching or tingling might indicate the onset of a flare, a physical change in the skin was confirmation of it. Examples of change in skin included dry, cracked, goosebumps, bloody, colour changes, tightness, roughness, thinning and thickening. A participant reported, ‘Texture transformation is a good indicator for me to know…this is part of a flare-up.’ Another said, ‘Always visible changes later…,’ meaning after some itching or other nonvisible symptom. One participant reported that changes in his skin that were noticed by other people helped him realize what a ‘bad flare’ was because the chronic nature of AD, and his inability to completely clear his skin meant he began to change his acceptability level of his skin to a ‘new normal’.

More attention needed/all-consuming focus

All participants shared, with some variation, that – at times – their AD takes a ‘front seat’ in their thoughts and at times fades to the ‘back seat’. Generally, participants wanted to forget they had AD and not have to think about taking care of themselves (some participants referred to this as ‘going on cruise control’ with their management). A flare was consistently defined as when the patient’s AD took more of their attention than usual (‘can’t stop thinking about it’ or no longer is ‘background noise’), sometimes because the treatment regimen needed to change or because they were constantly searching for possible causes of the flare. Some participants reported that they had better sleep once the flare went away because they did not have heightened anxiety and attention on their condition. ‘I know when a flare has ended…when it’s not actually loud and screaming; [no longer] in the forefront and I’m able to sleep.’

Itch–scratch–burn cycle

Itching and scratching and the subsequent burning and pain was a theme among all participants describing their flares. These symptoms were described as a chain reaction that set off (or cycle that aggravated) flares and was hard to get out of. One participant said: ‘Even before the itch, I feel a prick, like a heat or a warmth or a prickliness, that leads to the itch and then leads to the skin. And then it’s a whole chain reaction.’ Another participant shared: ‘My first indication that I’m entering the flare is when my skin starts to get thick and that’s because I’m already scratching…I struggle a lot with the itch–scratch cycle.’ Interestingly, one participant reported scratching without having a flare because they wanted to feel in control of their disease.

Control/lack of control and quality of life

Many participants discussed the role of control and frequency in defining a flare and severity of a flare. One participant shared, ‘The more severe the flare…the higher the frequency of the flare-ups, the less control that I feel.’ Another described what it’s like when a flare is over: ‘It’s like you’re back in cruise control and you don’t have to overthink anything, and you don’t see the red, you don’t feel the itch, you don’t feel the tightness. It’s like things are just flowing and resuming where you can focus on whatever is ahead of you without that being at the forefront of your mind.’ Some related this to the baseline, stating that the feeling of having control over the flare with medicine to where it is ‘manageable’ means the disease is in a controlled state and not flaring. Conversely, when participants described a flare as being something they lacked control over, some reported feeling like a ‘spectator’, distanced from others, as well as their normal self. One participant added that flares – which she defined as periods of lack of control – made her feel chronically ill and that ‘disability becomes a much larger part of [her] identity.’ We have located this construct in the middle of the framework to represent that it relates to and is affected in a very central way by all of the other themes described.

Figuring out the trigger

Flare was defined by participants based on how they experienced flare and when it started and stopped, yet all participants also shared how they coped with flares and tried to live a life with AD. While not a concept that defines a flare, the concern with figuring out the trigger that set the flare off was shared by all participants as part of the experience of a flare. One participant described their reaction to flaring as, ‘…and then it’s questioning, well, what causes [this]? Or what’s going on in my life? Or what do I need to change? Which I feel never really goes away, it’s that constant questioning then wondering, because it is chronic and sometimes it feels hopeless.’ The stress of trying to identify a trigger and sometimes not being able to figure it out took a toll on patients’ mental health and could be all-consuming.

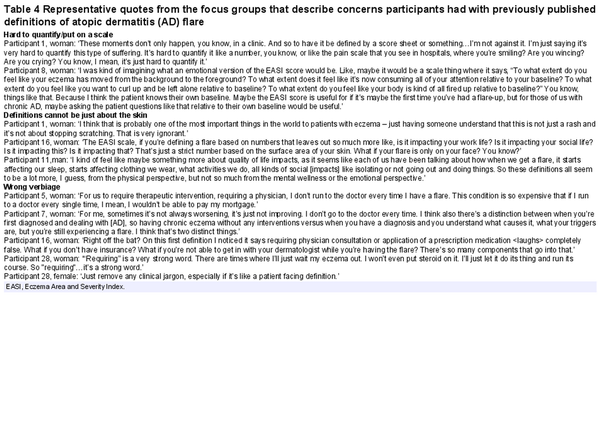

Participants’ reactions to existing atopic dermatitis flare definitions

Participants gave feedback on existing definitions that were shown in the focus groups as current definition examples. These existing definitions generally did not resonate with participants, who cited concerns in three categories: (i) flare was hard to quantify or put on a numerical scale; (ii) definitions cannot be just about skin; and (iii) existing definitions used incorrect verbiage or clinical verbiage that did not resonate with the patient (specifically ‘acute’ and ‘requiring consultation with a physician or treatment’). Representative quotes are provided in Table 4.

Discussion

In this qualitative study of adults with AD, we identified six concepts important to the definition of AD flare from the patient perspective: (i) changes from patient baseline/normal; (ii) mental, emotional and social consequences; (iii) physical changes in skin; (iv) more attention needed/all consuming focus; (v) itch–scratch–burn cycle; and (vi) control/lack of control and QoL. Identifying a trigger for a flare was an important underlying theme for participants related to how they experience and cope with a flare but did not contribute to how they define flare. These results highlight that although AD flares can be highly variable and complicated in nature, there are commonalities across the patient experience that can help to inform a patient-centred definition that may include multiple domains. Previously published definitions of AD flare did not resonate with participants, citing complications around trying to reduce a complex experience and symptoms of flare to a quantifiable number, as well as issues with medical jargon.

The domains identified as important to a patient-centred definition of flare are reflective of existing frameworks that describe the AD patient experience. A qualitative study by Howells et al. used online focus groups to explore perceptions of control among people with eczema and parents of children with eczema in the UK. The study aimed to understand patient and caregiver experiences and their understanding of the concept of control for the development of a core outcome set for eczema, which would eventually become the Recap of atopic eczema (RECAP) instrument. Participants used both the terms ‘control’ and ‘flare’ spontaneously to describe long-term control, and the terms were described differently across participants. However, this study did not seek to define ‘flare’. The conceptual framework proposed during the development of RECAP featured three main concepts that contribute to control: disease severity (including skin symptoms and ‘flares’); beyond the skin (including mental health and QoL); and treatment management (including upping or stepping down treatment). Many of the same themes identified in our study are represented in the RECAP framework, suggesting that a complex and interdependent group of concepts contribute to the AD experience.

The development of the Atopic Dermatitis Control Test (ADCT) also explored flare as a concept related to control, but in the end no item related to flare was included ‘given the overlapping and varying definitions of both flares and AD control, and the tendency to reference symptom exacerbations in defining an AD flare, which was already being captured’. Control has been identified by patients and healthcare providers alike as an important aspect of the AD experience. While the RECAP and ADCT frameworks do not define flare, they position the concept as affecting control, which has been captured in this study’s conceptual framework as one of the concepts that define flare.

Existing definitions, generally developed to measure disease activity, did not resonate with patients in this study. A recent editorial by Barbieri and MacDonald discussed the well-documented discordance in severity assessments as unsurprising, given the many factors affecting lived experience. The authors specifically noted the limitations of a numerical scale to measure severity, as clinicians and patients may have different references for scale endpoints. This supports this study’s finding that the concept of ‘patient’s baseline’ is important in defining flare and may explain the patient issue with definitions that include numerical rating scales.

Participants were sociodemographically diverse, improving the generalizability of the findings. Conducting virtual focus groups meant the study included geographically diverse US patients as well, including one participant from Hawaii. All participants had a self-reported AD flare in the past 12 months, which helped with recall bias when describing flare experiences. However, this group of 29 patients may not represent every type of patient with AD and their experiences. Specifically, all participants resided in the USA and were already well connected with the NEA and its resources, so their perspectives may differ from people living in other countries and people who are less inclined to engage with organizations such as the NEA.

This focus group study is the initial phase in a modified eDelphi study that aims to define AD flare from the patient perspective. This study’s results informed the consensus activities for the development of a patient-centred definition of AD flare conducted by the NEA.

Beyond this short-term application, this study’s results have implications for how flare is conceptualized and defined in clinical research and in clinical practice care conversations in the future. A provider’s awareness of a patient-informed definition of an AD flare could positively influence their patient-centred approach and provide a framework with which to better understand the flare experience of their patients. Attention to the personal nuances involved in flaring – such as patients’ significantly increased effort into management of their skin or a sense of loss of control and QoL due to flaring – inspires empathy and fosters trust, morale and understanding within the patient–provider relationship. Interpretation of a flare from a patient-informed perspective can also decrease the likelihood of discordance between patient and provider and agreement about when a patient is experiencing a flare, and underpin shared decision-making – a hallmark of patient-centred care. In the same vein, recognizing ‘figuring out a trigger’ as an underlying theme reminds providers to take the opportunity to reintroduce discussion into possible causes of the flare at an opportune time. Finally, highlighting mental health as a component of flaring encourages discussions related to mental health when patients present with a flare. Clinicians should be aware of the importance of flares to the patient experience of eczema, and how these may vary between patients. Developing management plans for flares, including preparation to cope with them psychologically, may also be beneficial.

This study provides a framework to understand what the concept of ‘flare’ means to adults with AD. More work is needed to further develop a patient-centred definition of AD flare.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and are grateful to the adults with atopic dermatitis who participated in the focus groups to share their lived experience with the disease.

References

- 1. Elsawi R, Dainty K, Begolka WS et al The multidimensional burden of atopic dermatitis among adults: results from a large national survey. JAMA Dermatol 2022; 158:887–92.

- 2. Shaw TE, Currie GP, Koudelka CW, Simpson EL. Eczema prevalence in the United States: data from the 2003 National Survey of Children’s Health. J Invest Dermatol 2011; 131:67–73.

- 3. Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M et al Atopic dermatitis in America study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol 2019; 139:583–90.

- 4. Wollenberg A, Christen-Zäch S, Taieb A et al ETFAD/EADV Eczema task force 2020 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults and children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34:2717–44.

- 5. Zuberbier T, Orlow SJ, Paller AS et al Patient perspectives on the management of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006; 118:226–32.

- 6. Thomas KS, Apfelbacher CA, Chalmers JR et al Recommended core outcome instruments for health-related quality of life, long-term control and itch intensity in atopic eczema trials: results of the HOME VII consensus meeting. Br J Dermatol 2021; 185:139–46.

- 7. Simpson E, Eckert L, Gadkari A et al Validation of the Atopic Dermatitis Control Tool (ADCT©) using a longitudinal survey of biologic-treated patients with atopic dermatitis. BMC Dermatol 2019; 19:15.

- 8. Pariser DM, Simpson EL, Gadkari A et al Evaluating patient-perceived control of atopic dermatitis: design, validation, and scoring of the Atopic Dermatitis Control Tool (ADCT). Curr Med Res Opin 2020; 36:367–76.

- 9. Langan SM, Thomas KS, Williams HC. What is meant by a “flare” in atopic dermatitis? A systematic review and proposal. Arch Dermatol 2006; 142:1190–6.

- 10. Girolomoni G, Busà VM. Flare management in atopic dermatitis: from definition to treatment. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2022; 13:20406223211066728.

- 11. Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL et al Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet 2021; 397:2151–68.

- 12. Merola JF, Sidbury R, Wollenberg A et al Dupilumab prevents flares in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in a 52-week randomized controlled phase 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021; 84:495–7.

- 13. Chalmers JR, Simpson E, Apfelbacher CJ et al Report from the fourth international consensus meeting to harmonize core outcome measures for atopic eczema/dermatitis clinical trials (HOME initiative). Br J Dermatol 2016; 175:69–79.

- 14. Bacci E, Rentz A, Correll J et al Patient-reported disease burden and unmet therapeutic needs in atopic dermatitis. J Drugs Dermatol 2021; 20:1222–30.

- 15. Abuabara K, Margolis DJ, Langan SM. The long-term course of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin 2017; 35:291–7.

- 16. Thomas KS, Stuart B, O’Leary CJ, Schmitt J et al Validation of treatment escalation as a definition of atopic eczema flares. PLOS ONE 2015; 10:e0124770.

- 17. Stuart BL, Howells L, Pattinson RL et al Measurement properties of patient-reported outcome measures for eczema control: a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021; 35:1987–93.

- 18. Langan SM, Schmitt J, Williams HC et al How are eczema ‘flares’ defined? A systematic review and recommendation for future studies. Br J Dermatol 2014; 170:548–56.

- 19. Howells LM, Chalmers JR, Gran S et al Development and initial testing of a new instrument to measure the experience of eczema control in adults and children: Recap of atopic eczema (RECAP). Br J Dermatol 2020; 183:524–36.

- 20. Keyes E, Borucki R, Feng R et al Preliminary definition of flare in cutaneous lupus erythematosus using the Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index. J Am Acad Dermatol 2022; 87:418–19.

- 21. Brunner HI, Klein-Gitelman MS, Higgins GC et al Toward the development of criteria for global flares in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res 2010; 62:811–20.

- 22. Ruperto N, Hanrahan LM, Alarcón GS et al International consensus for a definition of disease flare in lupus. Lupus 2011; 20:453–62.

- 23. Wu D, Bleier B, Wei Y. Definition and characteristics of acute exacerbation in adult patients with chronic rhinosinusitis: a systematic review. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020; 49:62.

- 24. Gaffo AL, Schumacher HR, Saag KG et al Developing a provisional definition of flare in patients with established gout. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64:1508–17.

- 25. Stewart S, Tallon A, Taylor WJ et al How flare prevention outcomes are reported in gout studies: a systematic review and content analysis of randomized controlled trials. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2020; 50:303–13.

- 26. Stewart S, Dalbeth N, Gaffo A. The challenge of gout flare measurement. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2021; 35:101716.

- 27. Stewart S, Guillen AG, Taylor WJ et al The experience of a gout flare: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2020; 50:805–11.

- 28. Parry E, Dikomitis L, Peat G, Chew-Graham CA. How do people with knee osteoarthritis perceive and manage flares? A qualitative study. BJGP Open 2022; 6:BJGPO.2021.0086.

- 29. Parry EL, Thomas MJ, Peat G. Defining acute flares in knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2018; 8:e019804.

- 30. King LK, Epstein J, Cross M et al Endorsement of the domains of knee and hip osteoarthritis (OA) flare: a report from the OMERACT 2020 inaugural virtual consensus vote from the flares in OA working group. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2021; 51:618–22.

- 31. Myasoedova E, De Thurah A, Erpelding ML et al Definition and construct validation of clinically relevant cutoffs on the Flare Assessment in Rheumatoid Arthritis (FLARE-RA) questionnaire. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2020; 50:261–5.

- 32. Hewlett S, Sanderson T, May J et al ‘I’m hurting, I want to kill myself’: rheumatoid arthritis flare is more than a high joint count – an international patient perspective on flare where medical help is sought. Rheumatology 2012; 51:69–76.

- 33. Bingham CO, Pohl C, Woodworth TG et al Developing a standardized definition for disease “flare” in rheumatoid arthritis (OMERACT 9 Special Interest Group). J Rheumatol 2009; 36:2335–41.

- 34. Bywall KS, Esbensen BA, Lason M et al Functional capacity vs side effects: treatment attributes to consider when individualising treatment for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 2022; 41:695–704.

- 35. Bartlett SJ, Barbic SP, Bykerk VP et al Content and construct validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the rheumatoid arthritis flare questionnaire: OMERACT 2016 workshop report. J Rheumatol 2017; 44:1536–43.

- 36. Alten R, Pohl C, Choy EH et al Developing a construct to evaluate flares in rheumatoid arthritis: a conceptual report of the OMERACT RA Flare Definition Working Group. J Rheumatol 2011; 38:1745–50.

- 37. Kirby JS, Moore B, Leiphart P et al A narrative review of the definition of ‘flare’ in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol 2020; 182:24–8.

- 38. Fuhlbrigge A, Peden D, Apter AJ et al Asthma outcomes: exacerbations. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 129:S34–48.

- 39. Costa N, Ferreira ML, Setchell J et al A definition of “flare” in low back pain: a multiphase process involving perspectives of individuals with low back pain and expert consensus. J Pain 2019; 20:1267–75.

- 40. Costa N, Smits EJ, Kasza J et al Low back pain flares: how do they differ from an increase in pain? Clin J Pain 2021; 37:313–20.

- 41. Costa N, Hodges PW, Ferreira ML et al What triggers an LBP flare? A content analysis of individuals’ perspectives. Pain Med 2020; 21:13–20.

- 42. Costa N, Ferreira ML, Cross M et al How is symptom flare defined in musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2018; 48:302–17.

- 43. Celli BR, Fabbri LM, Aaron SD et al An updated definition and severity classification of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations: the Rome proposal. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021; 204:1251–8.

- 44. Kirwan JR, De Wit M, Frank L et al Emerging guidelines for patient engagement in research. Value Health 2017; 20:481–6.

- 45. Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. SAGE , 2006.

- 46. Dainty KN, Seaton MB, O’Neill B, Mohindra R. Going home positive: a qualitative study of the experiences of care for patients with COVID-19 who are not hospitalized. CMAJ Open 2023; 11:E1041–7.

- 47. Howells LM, Chalmers JR, Cowdell F et al ‘When it goes back to my normal I suppose’: a qualitative study using online focus groups to explore perceptions of ‘control among people with eczema and parents of children with eczema in the UK. BMJ Open 2017; 7:e017731.

- 48. Barbieri JS, MacDonald K. Exploring discordance between patients and clinicians – understanding perceived disease severity. JAMA Dermatol 2023; 159:807–9.