WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This paper presents an empirically developed taxonomy of pressures and strategies providing a menu of options that can be used by clinical leaders and teams, to help them adapt when healthcare systems and organisations are under stress and simply cannot provide the standard of care they aspire to.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Much can be done in advance to anticipate and respond to pressures, but there are also a range of strategies that can be deployed on the day.

The taxonomies presented in this paper could be used by healthcare leaders to help them optimise how they adapt under pressure.

Introduction

Healthcare systems are operating under substantial pressures and will do so for the foreseeable future. Growing pressures include an ageing population, increased comorbidities and presence of long-term health conditions, and increasingly high standard of care expected by society, government, patients and professionals. The capacity of healthcare systems is limited, and many are experiencing substantial financial pressures and staff shortages, which have been further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare institutions have to try and balance the demand for care with the available resources. For example, emergency services often experience shifts where the number of patients and associated treatment needs exceed the available staff, equipment or physical space. Services, teams and individual professionals are constantly adapting in times of increased pressure, with adaptations made to staff allocation, patient flow and the functioning of services. The principal aim of these adaptations is to minimise the risks to patients and to maintain a reasonable quality and safety of care within the available constraints.

Adaptations are usually improvised and vary widely depending on who is in charge at the time. Strategies are often learnt on the job through experience and rarely explicitly taught to clinicians or managers. In contrast, many industries are now developing training programmes to specifically address conflicts between safety and productivity and to provide coordinated strategies for managing under pressure. However, to achieve this long-term goal in healthcare, we need to first develop a taxonomy of strategies to provide a foundation for subsequent definition and testing of strategies in practice which in turn could provide the basis for training programmes and further implementation and evaluation. Our study sets out to develop these taxonomies, by conducting a review of descriptive studies of healthcare settings adapting under pressure.

Our approach to developing a taxonomy of adaptive strategies relied on identifying studies of adaptation under pressure. We can trace discussions of adaptation in healthcare over decades, but the principal source of actual studies of adaptation comes from the field of resilience in healthcare. There are multiple definitions and characterisations of resilient healthcare, but most centre around the idea of managing unexpected variation and the ability to respond flexibly to changing demands. The resilient healthcare literature addresses resilience and adaptation at different levels of the system, for example, frontline worker, team, organisation.

The resilient healthcare literature describes examples of adaptations in clinical practice and uses them to advance theories of resilience engineering. The challenge for healthcare is how we translate this important theoretical area into everyday practice. The core data in some of these studies, before examined in the light of resilience theory, do contain descriptions of strategies for managing under pressure which we sought to extract. Empirical studies of resilience are helpful in this respect by providing descriptions of ‘work as done’, acknowledging the need for constant adaptation and adjustment in any work setting across healthcare. We reviewed the resilient healthcare literature and sought to extract adaptive strategies from these research papers.

In developing this taxonomy, we first carried out a scoping review, in which we identified empirical papers from the resilient healthcare literature which are relevant to understanding strategies healthcare professionals and organisations use to adapt under pressure. Our research questions were the following: (1) what types of pressures on the delivery of care are described in the studies? and (2) what strategies can be identified from resilient healthcare studies which can be used by frontline staff, teams or managers to manage when under pressure? We also sought to comment on the strategies that applied to different clinical areas where possible, and how specific strategies related to specific pressures. We used the core descriptions contained in these papers to develop a taxonomy of both pressures and the strategies clinicians and managers use to adapt and manage those pressures.

Methods

Overview of design and methodology

This was a two-phased approach (see study protocol). The first phase was to complete a scoping review to map the relevant concepts by systematically searching and synthesising the literature. We followed guidance set out by Arksey and O’Malley and refinements made by Levac et al. The second phase was to extract the pressures and strategies from these papers and develop a taxonomy of pressures and strategies used by frontline clinicians and managers. In this process, we followed guidance on taxonomy development processes adopted in related areas. Pressures referred to stresses on the system (eg, staff shortages) or other challenges, which mean clinicians need to revise their plans and strategies to deliver safe care. We defined ‘strategy’ as an action taken by individuals, teams or organisations to moderate the impact of pressures on a service. We focused on short-term/medium-term adaptations rather than long-term system or organisational change.

Phase 1: searching the literature

A full description of our search strategy and study selection is provided in online supplemental file 1. In brief, we conducted a systematic search across multiple databases using keywords for resilience in healthcare combined with keywords for pressures and responses to those pressures. For resilient healthcare, we used the definition of resilience by Wiig et al “… the capacity to adapt to challenges and changes at different system levels, to maintain high quality care.” We identified empirical studies using interviews or observation in which the primary participants were frontline clinicians or managers in charge of clinical areas. We included papers published anytime from inception up to 30 March 2022 and written in English. A sample were double coded, with high reliability (Cohen’s kappa=0.83), and the remainder shared between two researchers (BP and DI) for screening against the study criteria. The few discrepancies were discussed with a third researcher (CV). We extracted the following data items: title, authors, year of publication, country of study, type of clinical setting (eg, emergency medicine, maternity), data collection methodology (eg, interviews, ethnography) and participants (number of participants, job titles). For each paper, we identified pressures recorded and strategies adopted to manage those pressures.SP110.1136/bmjqs-2023-016686.supp1

Phase 2: development of the taxonomy

Categorisation of pressures and strategies

We identified pressures (eg, lack of cubicle space to assess and treat patients) and strategies (eg, managers shedding managerial tasks to assist with clinical work) from the different papers included in this scoping review. BP and DI first familiarised themselves with the papers and then systematically coded pressures or strategies reported in the papers, using NVivo software. The list of extracted pressures and strategies was cross-checked by both authors, to ensure each extracted item met the definitions.

In order to develop the taxonomies, the researchers then began the process of working from codes to sub-themes, grouping similar pressures and strategies. We followed guidance on taking an empirical to conceptual approach to taxonomy development. We used an inductive thematic analysis approach: the process was heavily iterative and began by grouping codes which were very similar, for example, codes relating to a shortage of staff numbers (example of a pressure) or codes relating to prioritising workload (example strategy). The research team met weekly with a third researcher (CV) to discuss the development of the themes and sub-themes. The authors examined the papers included in the review for examples of themes or groupings used by others, for example, Back et al, distinguish between strategies for increasing capacity, reducing demand and increasing efficiency which influenced the groups for our taxonomy of strategies. A decision was made to distinguish between strategies used on the day and strategies used in anticipation of pressures. Initially, we thought pressures might be able to be grouped in a shortage of various types of resource (eg, staff, equipment), but it was clear from the data extracted that there were other problems relating to working conditions and system functioning. The Donabedian Structure-Process-Outcome model and the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) influenced our groupings for the taxonomy of pressures. After extensive discussion and review, we developed a hierarchical taxonomy for pressures and strategies. The taxonomies were presented to other researchers and clinicians for feedback, and adjustments were made to the language to improve clarity.

Results

Phase 1: findings of scoping review and identification of pressures and strategies

The database search returned 7671 articles. After the removal of 2269 duplicates, the title and abstracts were screened for 5402 papers. Two hundred and twenty-nine papers were included for full-text review and 17 papers met the full inclusion criteria (PRISMA diagram available in online supplemental file 2). Information about the included studies is available in online supplemental file 3.

SP210.1136/bmjqs-2023-016686.supp2SP310.1136/bmjqs-2023-016686.supp3

In the 17 studies included, we extracted 166 pressures and 348 strategies. An example pressure extracted from the papers was that the intended increase in capacity was compromised by skill-mix problems. An example strategy (to address problems with skill mix) was to have mixed care teams with at least one experienced staff member to counterbalance and support the high number of junior staff. Box 1 lists some examples pressures and strategies extracted. After extracting all the pressures and strategies meeting our definitions, we began to develop the taxonomies.

Box 1Examples of pressures and strategies extracted from the included papers

Back et al (Emergency Department, UK)

Examples of pressures extracted:

Limited scope to relocate patients because of the physical limitations of the space.

Lack of cubicle space to assess and treat patients.

Examples of strategies extracted for responding to these pressures:

Relocating patients by sending them to another service.

Relocating patients to a less busy area within the emergency department.

Expediting patient transfers to other areas in the emergency department.

Hybinette et al (Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, Sweden)

Example of pressures extracted:

Managers face situations where they must balance a limited number of staff with demands for high occupancy.

Examples of strategies extracted for responding to these pressures:

Managers shedding managerial tasks for participating in clinical emergency work.

Putting twins together in one cot, thereby utilising one nurse to care for three babies which is more than the goal of two babies per nurse. This manoeuvre created an opportunity to temporarily handle five patients (with one empty emergency cot) in a room with staffing for four.

Phase 2: a taxonomy of pressures and strategies

After extracting all the pressures and strategies from the included papers, we set out to develop a taxonomy of pressures and strategies. After successive iterations, described above, we established four broad classes of pressures and knock-on effects for clinical work that precipitated adaptations. We identified two broad classes of adaptive strategies, anticipatory strategies to prepare for pressures and those used on-the-day to manage immediate pressures.

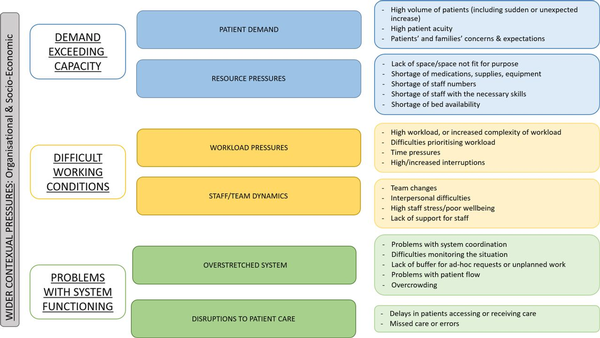

Pressures

There were contextual pressures described in the studies that were external to the clinical teams concerned and pressures experienced within organisations which were almost exclusively due to the demand for care exceeding the resources available. These two sources of pressures had consequences for the working conditions for staff and for wider system functioning. For clarity, we describe four separate categories of pressures and their knock-on effects on clinical work, though in practice they relate to fluid and dynamic ways as we discuss at the end of this section. These are (1) contextual pressures, (2) demand exceeding capacity, (3) difficult working conditions and (4) problems with system functioning. Figure 1 shows the taxonomy of pressures and their effects on clinical work and figure 2 shows how they interrelate. Specific examples for the different categories of pressures are available in online supplemental file 4.SP410.1136/bmjqs-2023-016686.supp4

Figure 1

A taxonomy for pressures and their effects on clinical work.

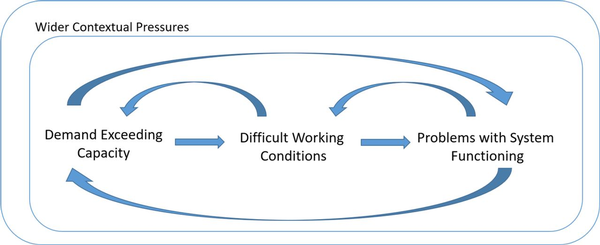

Figure 2

An illustration of how pressures and their effects interrelate.

Contextual pressures

Contextual pressures relate to factors external to the clinical team, which are affecting the care the service can provide. These include wider pressures affecting society during the time of the study, such as COVID-19 or socioeconomic factors, and organisational pressures within the health and care system, such as constraints in funding or the consequence of pressures in other parts of the system such as social care.

Demand exceeding capacity

Studies identified a mismatch between capacity and demand as the primary source of pressure on the system. Many of the studies described pressures related to increased patient demand which included high numbers, sudden inflows and increased acuity. Studies also described limitations in capacity which most commonly related to staff shortages (numbers or skill-mix issues) but also a lack of adequate space and issues with supplies and equipment (which was particularly evident in studies in lower-middle income countries).

Difficult working conditions

The primary and most immediate impact of excessive demand is of course an increased workload for staff, with ensuing difficulty in managing and prioritising workload. This increased workload was often compounded by time pressures and interruptions or ad hoc requests, particularly in emergency department and pharmacy settings. Disruptive team changes, interpersonal difficulties and high staff stress were noted as contributory to poor working conditions.

Problems with system functioning

An imbalance between system capacity and patient demand coupled with increasingly difficult working conditions can lead to a decline in broader system functioning. Several studies referred to problems with co-ordination and communication across the system, making it difficult to monitor resource availability or manage changing priorities along the patient journey. Other system pressures included a reduced buffer capacity for responding to ad hoc requests or sudden increase in demand. Many studies cited pressures relating to patient flow, whether that was a difficulty in discharging patients or bottlenecks within the hospital, as well as problems with overcrowding particularly in the emergency department. Delays in patients accessing or receiving care as well as missed care or errors were additional problems which further increased the workload and patient demand.

Interrelating pressures

External pressures impact on capacity/demand, which in turn affects working conditions, which in turn may degrade system functioning. In reality of course, there are multiple feedback loops and interactions between the different pressures and problems. For instance, once a system begins to run less effectively, backlogs of patients accumulate which impacts on capacity and demand, which affects working conditions and so on. Box 2 contains examples from high and low to middle-income countries illustrating how these pressures interact with each other, creating a ‘domino effect’ through the system.

Interactions between pressuresKagwanja et al: Kenya, Health System

A lack of funding (organisational pressures) created shortages in supplies and equipment (resource pressures) leading to staff lateness or absence, further compounding the pressures of resources and consequently delaying patients receiving care (patient care).

Alameddine et al: Lebanon and Jordan, Healthcare Facilities

War and conflict in Syria (socio-economic pressures) had resulted in an influx of refugees arriving in Lebanon with their own language and expectations of healthcare (patient demand). This drastically increased the number of patients being seen and complexity relating to language barriers and trauma (workload pressures), which in turn created increased stress for staff trying to accommodate this (staff/team dynamics).

Wears et al: USA, Emergency Department

A sudden inflow of acute patients (patient demand) combined with a lack of space (resource pressures) leads to overcrowding (overstretched system) leading to a loss of monitoring and coordination (overstretched system). This loss of monitoring could mean bed availability is not being updated causing further problems with patient flow.

Anderson et al: UK, Emergency Department and Older Person’s Unit

Pressures in other parts of the system such as community or social care (organisational pressures) result in patients being unable to be discharged from hospital (overstretched system). This ultimately creates a shortage of bed availability for the high number of patients that come in requiring care (resource pressures).

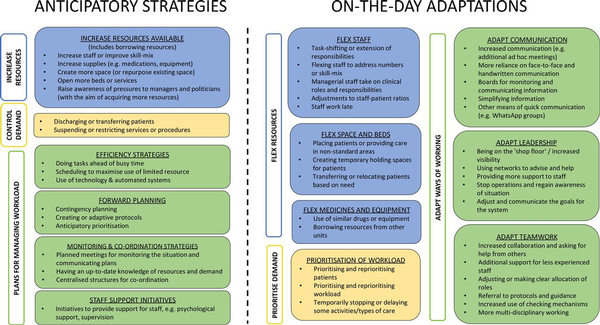

Anticipatory strategies

We found that anticipatory strategies could be broadly grouped into those aimed at managing capacity and demand and those which were aimed at making plans to manage the workload in anticipation of forthcoming pressures. Figure 3 shows a full taxonomy of strategies. For more detailed examples, see online supplemental file 4.

Figure 3

A taxonomy of strategies for adapting to pressures. The taxonomy includes two broad classes of adaptive strategies: anticipatory strategies to prepare for pressures and on-the-day adaptations to manage immediate pressures.

Increase resources

The essential problem staff face is that the resources available, of various kinds, are not adequate for the demands on the system. One option in anticipation of pressures is to increase the available resources, whether that be staff, supplies, space or beds/services. This may involve paying for extra staff or overtime shifts, running training courses to upskill staff to improve skill mix, opening new services or putting on extra clinics to meet increased demand. Studies described borrowing resources from elsewhere in the system and repurposing existing space like using operating theatres for temporary intensive care overflow.

Control demand

The other alternative to a mismatch between resource and demand is to try to reduce demand or at least postpone it. Strategies here included discharging patients earlier than planned or transferring them to other units or services. Other strategies involved making the decision to suspend or restrict certain services, procedures or supplies.

Plans for managing the workload

Studies reported a variety of anticipatory strategies to manage workload; some aimed at moving clinical tasks or clinics to a less pressured time and some aimed at reducing workload on the day. For instance, staff might plan to carry out tasks ahead of a busy period, such as mixing drugs ahead of time in pharmacy. Other approaches included scheduling to optimise resources such as arranging clinics to run on different days to maximise the use of the available space or increased reliance on telephone/video consultations.

Other strategies focused on forward planning to manage the workload at the time of pressures. For example, a pharmacist created a list of tasks, what to prioritise and look out for, for the covering pharmacist. Other studies suggested adapting or creating new protocols in anticipation of pressures. A few studies described contingency planning strategies or setting up regular meetings for monitoring and communicating plans. Some studies described systems for accurately monitoring the available resources and demand, which was necessary for optimising the allocation of resources under pressure. Finally, some studies described interventions to support staff well-being.

On-the-day Adaptations

As with anticipatory strategies, we were able to classify adaptations made on the day into those addressing use of resources, those addressing demand, and adapting ways of working (figure 3; online supplemental file 4).

Flex resources

Most of the on-the-day strategies focused on re-allocating existing resources. Nearly all the included studies described flexing their existing staff by, for example, task shifting, re-allocating staff between units, adjusting staff–patient ratios or managerial staff taking on clinical roles. One study mentioned assistance from family members of patients to assist with the workload. Sometimes the existing staff simply stayed late to cover the workload.

Many of the studies also described adaptations to the use of existing space and beds, such as creating temporary holding spaces for patients (eg, stretchers or chairs) or delaying patients in the operating theatre, for example, before being moved to intensive care. Another strategy was to transfer patients to other units or hospitals. Two studies described borrowing supplies from other units or replacing with similar drugs or equipment.

Prioritise demand

Prioritisation of patients according to clinical need is a core professional responsibility but the adaptive strategies described here mainly involved wider prioritisation of care in order to maintain patient safety and a reasonable, if not ideal, standard of care. For example, in a study of neonatal intensive care, managers prioritised readiness and clinical capacity in some parts of the ward while maintaining family-centred care and staff education in others. Some tasks get deprioritised leading to delays in care, such as increasing the wait-time for ECGs for patients with chest pain due to pressures in the emergency department.

Adapt ways of working

Many studies described how clinicians, teams and leaders adapt the way they communicate when under pressure. Several studies described additional ad hoc meetings to share information and make decisions, as well as more reliance on verbal and handwritten communication and using notes and boards to update staff and families.

Leadership strategies included using your networks to proactively problem-solve and leaders spending more time ‘on the shop floor’ when the pressures were high, which enabled them to gather up-to-date information and be available to support staff. When pressure is very high, there can be a fragmentation of care to patients which can lead to a more general sense of losing control. In this highly dangerous situation, leaders may decide to briefly stop all clinical activities in order to regain control. The aim of this strategy is to identify who the patients are, what their basic problems are and which workers will be responsible for which patient, and then begin operations again with improved situational awareness.

Some studies described adaptations to teamwork when under pressure. Several studies mentioned asking for help and increased collaboration between different disciplines or increased support for new or inexperienced team members. An additional emphasis on clear allocation of roles was noted in several studies, as well as the use of protocols and guidance for providing essential care.

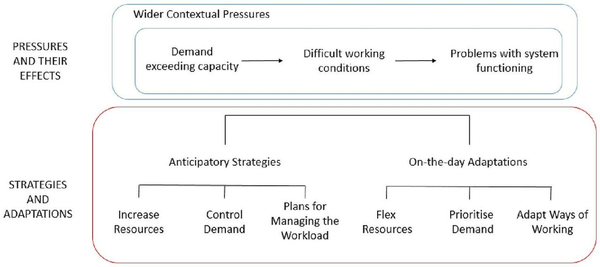

Conceptual Framework

Figure 4 presents an overarching conceptual framework for the pressures and adaptive strategies described above. Many of the pressures lead to and interact with other pressures. The broad categories of anticipatory strategies are similar but subtly different to the on-the-day adaptations. In practice, teams and leaders combine many of these strategies together in response to specific pressures in effect using a portfolio of adaptive strategies.

Figure 4

Simplified conceptual framework to illustrate the pressures and strategies for responding to these pressures.

Discussion

This paper presents a taxonomy of strategies and pressures, which have been empirically derived from descriptive studies of health systems adapting under pressure. Although healthcare systems face multiple challenges, the dominant source of pressure is that demand for care exceeds resources available. When demand exceeds capacity, working conditions become more difficult which in turn increases risk to patients which creates more pressure on staff. The main contribution of our paper is to organise these strategies into a conceptual framework and outline a portfolio of strategies available to clinical leaders to manage pressure effectively.

Clinical leaders need to employ a portfolio of strategies when pressures are high, selecting and deploying from the full range of adaptive strategies available. Strategies can be separated out into actions that can be done in advance in anticipation and actions that can be done on the-day, although often concerned with the same form of adaptation. For instance, planning for leaders to increase direct clinical involvement and communicating that to staff in advance enable more effective adaptation by leaders on the day. Many of the basic strategies appear to be similar across different clinical settings, though often customised to context. Task shifting, for instance, is used across many different settings, between different professions and different grades within the same profession (eg, the studies by Aurizki and Wilson, Federspiel et al, Seidman and Atun), though tasks can also be shifted to students and support staff in some circumstances. Leaders and teams employ multiple strategies in combination to maintain safety and manage patient flow. For instance, strategies to manage demand are employed alongside adaptations to ways of working, to achieve maximum protection for patients and support for staff. Further work is needed to explore how these strategies vary by clinical setting.

Adaptation is a dynamic process

A taxonomy of course can never capture the very complex and evolving patterns of care in a clinical environment under pressure. While we believe that developing a taxonomy is a necessary step to further study and evaluate the adaptive strategies, we are aware that a taxonomy alone does not capture the phenomenon of adaptive capacity and that successful adaptation requires much more than simply a knowledge of adaptive strategies. First, the actions of individual clinicians will be either supported or constrained by the wider capacity of the system to anticipate, monitor, respond and learn. Second, there may well be trade-offs between short-term and long-term adaptive capacity, in that successful adaptation on the day can have the effect of reducing capacity to meet future threats. Third, adaptive capacity is a finite resource and dependent to some extent on having some spare capacity in a system, in the sense of staff, skills and resources that can be drawn on to meet increased demand. In order to put some adaptive strategies into practice, there needs to be ‘slack’ or ‘margins’ in the system, as well as access to additional resources. A system that prioritises productivity above all else will eventually degrade its capacity to adapt.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this study is that the taxonomies were systematically developed from a review of existing studies, which represented a range of different clinical settings and countries. For pragmatic reasons, we focused our scoping review on resilient healthcare studies, and this has proved sufficient for developing the taxonomies and portfolio of strategies. However, some other papers outside the resilient healthcare also refer to strategies for adapting under pressure and could be incorporated in future work on adaptive strategies in particular settings. Further strategies might be identified in, for instance, the literature on nursing workarounds (eg, the study by Debono et al), which could be used both to evolve and to develop the taxonomies in different contexts. Furthermore, most of the studies included in this review focused on hospital care: further validation of the taxonomies is needed for other settings such as primary care.

Implications for clinical practice

The principal practical benefit of this taxonomy is that it translates more theoretical work on resilience into approaches useful in everyday practice. Leaders make adaptations all the time in response to pressures, but few have an explicit model or training on how to do this. The taxonomy could be used as the basis of training programmes for clinical teams in responding to organisational threats and pressures as proposed by Amalberti and Vincent. Training would involve formal teaching or lectures on strategies and relevant theoretical issues but would primarily be scenario-based workshops or simulations to support guided self or group reflection. Each clinical team or department needs to evolve their own approach and repertoire within their own context. This kind of training is likely to be particularly useful for those new to leadership positions who are responsible for the functioning of a service and have the authority to guide and support team and system-level adaptations. When pressure is high, a coordinated strategy of controlling demand and adapting ways of working is likely to be much safer than a fragmented and individualised set of improvisations.

Future research

Taxonomies are intended to be expanded and to evolve over time. The taxonomies presented here now need further testing and validation. It is possible that further categories or subcategories will emerge. The taxonomies also need testing out in different clinical settings: the studies in this review were primarily studying hospital settings, and there were no studies set in primary care or mental health for example.

All strategies have benefits and risks, and few of the papers in our review address the effectiveness of any of the strategies described. The assessment of the effectiveness of different strategies for managing under pressure is a critical topic for future research. The creation of a taxonomy is the first step towards the evaluation of the impact of different strategies or combinations of strategies on the safety of patients, well-being of staff and wider organisational performance. There may be certain strategies or combinations of strategies that are better than others or have differential trade-offs and impact on safety, staff well-being, patient flow and patient experience. Strategies may also of course have adverse effects or unintended secondary consequences. For example, staff staying late to cover a shift may improve patient safety but will clearly have a negative impact on staff well-being. Systems that rely on individuals adapting at maximum capacity every day leave no margin to respond to unusual demands, and there is a limit to the benefit of some strategies especially when used frequently.

Conclusions

We have developed an empirically based taxonomy of pressures and an accompanying taxonomy of strategies which can support clinical leaders in developing a coordinated approach to working under pressure. Defining the taxonomies and portfolio of strategies provides a basis for testing the effectiveness of different strategies and the development and evaluation of interventions to manage under pressure. Adaptation does not need to be entirely improvised but can be planned with an underlying logic and coordination across clinical teams and organisations.

We thank Jane Carthey and Helen Higham for their comments on the manuscript and feedback on the taxonomies.

X @bethanpage21

Contributors BP and CV conceived the review and taxonomy development and all authors contributed to its design. BP and DI conducted the scoping review and the analysis for developing the taxonomies, supervised by CV. BP drafted the manuscript with support from DI, CV and RA. All authors reviewed and agreed on the current version. BP is the guarantor for this study

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1. Back J, Ross AJ, Duncan MD, et al. Emergency Department escalation in theory and practice: A mixed-methods study using a model of organizational resilience. Ann Emerg Med 2017;70:659–71. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.04.032

- 2. Son C, Sasangohar F, Rao AH, et al. Resilient performance of emergency Department: patterns, models and strategies. Safety Science 2019;120:362–73. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2019.07.010

- 3. Amalberti R, Vincent C. Managing risk in hazardous conditions: improvisation is not enough. BMJ Qual Saf 2020;29:60–3. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009443

- 4. Hybinette K, Pukk Härenstam K, Ekstedt M. A first-line management team’s strategies for sustaining resilience in a specialised intensive care unit—a qualitative observational study. BMJ Open 2021;11:e040358. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040358

- 5. Rasmussen J. Risk management in a dynamic society: a Modelling problem. Safety Science 1997;27:183–213. doi:10.1016/S0925-7535(97)00052-0

- 6. Vincent C, Benn J, Hanna GB. High reliability in health care BMJ. BMJ 2010;340(jan19 2):bmj.c84. doi:10.1136/bmj.c84

- 7. Sutcliffe KM, Paine L, Pronovost PJ. Re-examining high reliability: actively organising for safety. BMJ Qual Saf 2017;26:248–51. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004698

- 8. Rotteau L, Goldman J, Shojania KG, et al. Striving for high reliability in Healthcare: a qualitative study of the implementation of a hospital safety programme. BMJ Qual Saf 2022;31:867–77. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2021-013938

- 9. Hollnagel E, Sujan M, Braithwaite J. Resilient health care–making steady progress. Safety Science 2019;120:781–2. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2019.07.029

- 10. Iflaifel M, Lim RH, Ryan K, et al. Resilient health care: a systematic review of Conceptualisations, study methods and factors that develop resilience. BMC Health Serv Res 2020;20:324. doi:10.1186/s12913-020-05208-3

- 11. Wiig S, Aase K, Billett S, et al. Defining the boundaries and operational concepts of resilience in the resilience in Healthcare research program. BMC Health Serv Res 2020;20:330. doi:10.1186/s12913-020-05224-3

- 12. Page B, Irving D, Vincent C. Strategies for managing under pressure: A protocol for a Scoping review of observational studies from the resilient health care literature. Open Science Framework 2022.

- 13. Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:1291–4. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013

- 14. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2005;8:19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616

- 15. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- 16. Lawton R, McEachan RRC, Giles SJ, et al. Development of an evidence-based framework of factors contributing to patient safety incidents in hospital settings: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:369–80. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000443

- 17. Nickerson RC, Varshney U, Muntermann J. A method for Taxonomy development and its application in information systems. European Journal of Information Systems 2013;22:336–59. doi:10.1057/ejis.2012.26

- 18. Donabedian A. The quality of care: how can it be assessed? JAMA 1988;260:1743–8. doi:10.1001/jama.260.12.1743

- 19. Carayon P, Schoofs Hundt A, Karsh B-T, et al. Work system design for patient safety: the SEIPS model. Qual Saf Health Care 2006;15 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i50–8. doi:10.1136/qshc.2005.015842

- 20. Carayon P, Wooldridge A, Hoonakker P, et al. SEIPS 3.0: human-centered design of the patient journey for patient safety. Appl Ergon 2020;84:103033. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2019.103033

- 21. Holden RJ, Carayon P, Gurses AP, et al. SEIPS 2.0: a human factors framework for studying and improving the work of Healthcare professionals and patients. Ergonomics 2013;56:1669–86. doi:10.1080/00140139.2013.838643

- 22. Saurin TA, Wachs P, Bueno WP, et al. Coping with complexity in the COVID pandemic: an exploratory study of intensive care units. Hum Factors Ergon Manuf 2022;32:301–18. doi:10.1002/hfm.20947

- 23. Patterson MD, Wears RL. Resilience and precarious success. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2015;141:45–53. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2015.03.014

- 24. Peat G, Olaniyan J, Fylan B, et al. Mapping the resilience performance of community Pharmacy to maintain patient safety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Res Social Adm Pharm 2022;18:3534–41. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2022.01.004

- 25. Anderson JE, Ross AJ, Back J, et al. Beyond ‘find and fix’: improving quality and safety through resilient Healthcare systems. Int J Qual Health Care 2020;32:204–11. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzaa007

- 26. Wachs P, Saurin TA, Righi AW, et al. Resilience skills as emergent phenomena: A study of emergency departments in Brazil and the United States. Appl Ergon 2016;56:227–37. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2016.02.012

- 27. Juvet TM, Corbaz-Kurth S, Roos P, et al. Adapting to the unexpected: problematic work situations and resilience strategies in Healthcare institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic’s first wave safety science. Saf Sci 2021;139:105277. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105277

- 28. Wears RL, Perry SJ, McFauls A. Free fall-a case study of resilience, its degradation, and recovery, in an emergency Department. In2nd International Symposium on Resilience Engineering; Juan-les-Pins, France: Mines Paris Les Presses, 2006

- 29. Miller A, Xiao Y. Multi-level strategies to achieve resilience for an Organisation operating at capacity: a case study at a trauma centre. Cogn Tech Work 2007;9:51–66. doi:10.1007/s10111-006-0041-0

- 30. Kagwanja N, Waithaka D, Nzinga J, et al. Shocks, stress and everyday health system resilience: experiences from the Kenyan coast. Health Policy Plan 2020;35:522–35. doi:10.1093/heapol/czaa002

- 31. Gifford R, Fleuren B, van de Baan F, et al. To uncertainty and beyond: identifying the capabilities needed by hospitals to function in dynamic environments. Med Care Res Rev 2022;79:549–61. doi:10.1177/10775587211057416

- 32. Scott JW, Lin Y, Ntakiyiruta G, et al. Contextual challenges to safe surgery in a resource-limited setting: a multicenter, Multiprofessional qualitative study. Ann Surg 2018;267:461–7. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000002193

- 33. Alameddine M, Fouad FM, Diaconu K, et al. Resilience capacities of health systems: accommodating the needs of Palestinian refugees from Syria. Social Science & Medicine 2019;220:22–30. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.10.018

- 34. Anders S, Woods DD, Wears RL, et al. Limits on adaptation: modeling resilience and Brittleness in hospital emergency. learning from diversity: model-based evaluation of opportunities for process (Re)-Design and increasing company resilience; 2006. 1.

- 35. Göras C, Nilsson U, Ekstedt M, et al. Managing complexity in the operating room: a group interview study. BMC Health Serv Res 2020;20:440. doi:10.1186/s12913-020-05192-8

- 36. Altare C, Castelgrande V, Tosha M, et al. From insecurity to health service delivery: pathways and system response strategies in the Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Glob Health Sci Pract 2021;9:915–27. doi:10.9745/GHSP-D-21-00107

- 37. Hollnagel E. n.d. Safety-II in practice: developing the resilience potentials. Taylor & Francis;2017:31–5. doi:10.4324/9781315201023

- 38. Aurizki GE, Wilson I. Nurse‐Led Task‐Shifting strategies to substitute for mental health specialists in primary care: A systematic review. Int J Nurs Pract 2022;28:e13046. doi:10.1111/ijn.13046

- 39. Federspiel F, Mukhopadhyay S, Milsom PJ, et al. Global surgical, obstetric, and anesthetic task shifting: a systematic literature review. Surgery 2018;164:553–8. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2018.04.024

- 40. Seidman G, Atun R. Does task shifting yield cost savings and improve efficiency for health systems? A systematic review of evidence from low-income and middle-income countries. Hum Resour Health 2017;15:29. doi:10.1186/s12960-017-0200-9

- 41. Nzinga J, McKnight J, Jepkosgei J, et al. Exploring the space for task shifting to support nursing on neonatal wards in Kenyan public hospitals. Hum Resour Health 2019;17:18. doi:10.1186/s12960-019-0352-x

- 42. Woods DD, Wreathall J. Stress-strain plots as a basis for assessing system resilience. In: Resilience Engineering Perspectives Volume 1. CRC Press, 2016: 157–72.

- 43. Woods DD, Chan YJ, Wreathall J. The stress–strain model of resilience Operationalizes the four cornerstones of resilience engineering. In5th Resilience Engineering Symposium; 2014:17–22

- 44. Woods DD. The theory of graceful Extensibility: basic rules that govern adaptive systems. Environ Syst Decis 2018;38:433–57. doi:10.1007/s10669-018-9708-3

- 45. Chuang S, Woods DD, Reynolds M, et al. Rethinking preparedness planning in disaster emergency care: lessons from a beyond-surge-capacity event. World J Emerg Surg 2021;16:59. doi:10.1186/s13017-021-00403-x

- 46. Debono DS, Greenfield D, Travaglia JF, et al. Nurses' Workarounds in acute Healthcare settings: a Scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:175. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-13-175

- 47. Fisher RF, Croxson CH, Ashdown HF, et al. GP views on strategies to cope with increasing workload: a qualitative interview study. Br J Gen Pract 2017;67:e148–56. doi:10.3399/bjgp17X688861

- 48. Macrae C, Wiig S. Resilience: from practice to theory and back again. exploring resilience a scientific journey from practice to theory. Cham: Springer Open, 2019: 121–8.

- 49. Motola I, Devine LA, Chung HS, et al. Simulation in Healthcare education: a best evidence practical guide. Med Teach 2013;35:e1511–30. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2013.818632

- 50. Haraldseid-Driftland C, Dombestein H, Le AH, et al. Learning tools used to translate resilience in Healthcare into practice: a rapid Scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 2023;23:890. doi:10.1186/s12913-023-09922-6