Introduction

It is widely acknowledged that the characteristics, management, and outcomes for patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) vary across the world []. In Asia, where two-thirds of global stroke deaths occur, the burden of AIS is particularly heavy as patients are relatively young and have challenges accessing evidence-based care [-]. The effectiveness of early reperfusion therapy with intravenous thrombolysis for AIS is well established [], but most of the randomized evidence has been derived from Caucasian populations []. Few studies have examined the high frequency of intracranial atherosclerosis and cerebral small vessel disease, and an apparent greater risk of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), influence outcomes in thrombolyzed Asian AIS patients. Herein, we present analyzes of how differing demographic, clinical, and management variables between Asian and non-Asian thrombolyzed AIS patients are associated with clinical outcomes in the Enhanced Control of Hypertension and Thrombolysis Stroke study (ENCHANTED).

Methods

Study Design

The ENCHANTED trial was an international, multicenter, partial-factorial, prospective, randomized, open-label, blinded endpoint clinical trial, the details of which are outlined elsewhere [-]. In brief, a total of 4,551 AIS patients fulfilling standard criteria for thrombolysis treatment were randomly assigned to low-dose (0.6 mg/kg) or standard-dose (0.9 mg/kg) intravenous alteplase (rtPA) and/or intensive (target systolic blood pressure [SBP] 130–140 mm Hg) or guideline-recommended (SBP <180 mm Hg) BP management between March 2012 and April 2018. Participants were grouped into major regional groups: Asian patients were defined according to standard criteria as from China mainland, Hong Kong and Taiwan, India, Korea, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam, while non-Asia patients were those from elsewhere including from Australia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Italy, Norway, Spain, and the United Kingdom (online suppl. Table 1; see http://www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000516487 for all online suppl. material, outlines patient numbers by country). The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee at each participating hospital center, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient or an appropriate surrogate.

Procedures

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were obtained at the time of patient enrolment, and outcome data were collected at 24 and 72 h, and 7 (or at hospital discharge, if earlier), 28 and 90 days. Neurological severity was measured on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) at baseline, 24 h, and 3 days. Functional outcome of death or disability was assessed on the modified Rankin scale (mRS), administered by trained researchers kept blind to treatment allocation, by telephone or in-person interview at 90 days. Uncompressed digital images of all baseline and follow-up brain scans were uploaded for central analyzes by at least two independent assessors blind to other data using MIStar software, version 3.2 (Apollo Medical Imaging Technology, Melbourne, Australia). Assessors graded any ICH as intracerebral, subarachnoid, intraventricular, subdural, or other.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was death and disability, defined as the mRS scores 2–6 at 90 days. Other functional outcomes included major disability (mRS scores 3–5) and death at 90 days, and death or neurological deterioration (≥4 points decline in NIHSS scores) at 24 h and 3 days. The key safety outcome was any ICH within 90 days.

Statistical Analysis

Associations of Asian versus non-Asian regional and functional and safety outcomes were estimated in logistic regression models, with adjustment for key baseline prognostic covariates of age, sex, premorbid function (estimated mRS score 0 vs. 1), use of antithrombotic treatment, history of hypercholesterolemia, atrial fibrillation, current treatment for hypertension, baseline SBP, time from symptom onset to randomization, final diagnosis of AIS subtype, rtPA dose, and mean SBP 1–24 h post-randomization. Data are reported with adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), with a 2-sided p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. All analyses involved SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) [, ].

Data Sharing

De-identified participant data used in these analyses can be shared by formal request to the corresponding author.

Results

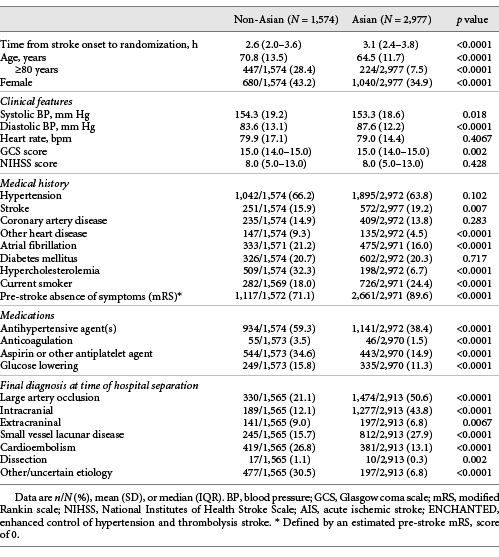

A total of 4,551 thrombolyzed AIS patients (mean age 66.7 years, 37.8% female) were included in these analyzes. Table 1 outlines the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of AIS patients by regions. Compared to non-Asians, Asian patients were younger, less history of atrial fibrillation and hypercholesterolemia, lower use of antihypertensive, glucose lowering, antiplatelet, and statin therapy before stroke onset, and more likely to have had a previous stroke. However, the frequencies of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and coronary heart disease were comparable between groups. Although Asian patients were more likely to have AIS due to large vessel occlusion, especially from intracranial atherosclerotic disease, or small vessel “lacunar” disease, and less cardioembolic origin, than non-Asians, neurological severity according to the NIHSS was similar between the two groups.

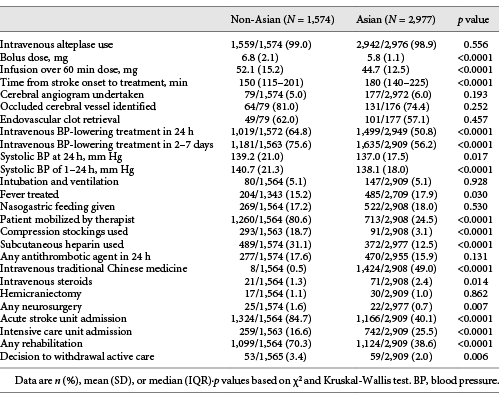

Table 2 highlights differences in the use of intravenous alteplase and early in-hospital management, where overall Asian patients received a lower dose of alteplase, both bolus and infusion, mainly due to having a lower body weight, and it was administered at a later time from symptom onset (180 min vs. 150 min, p < 0.0001, Table 2) compared to non-Asians. Although there was less use of BP-lowering treatment, Asians had a greater reduction in achieved mean SBP over 24 h than non-Asians (138.1 mm Hg vs. 140.7 mm Hg; p < 0.0001, Table 2). Asian patients also had lower admission to an acute stroke unit and use of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, neurosurgery, mobilization by therapist and rehabilitation, and withdrawal of care measures but were more likely to receive intensive care, anti-pyrexia treatment, intravenous steroids, and traditional Chinese medicine, than non-Asians.

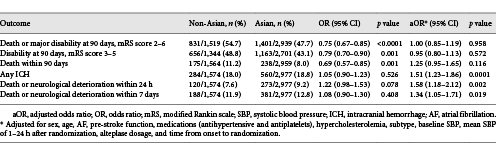

In regard to clinical outcomes, there was no significant difference in the primary outcome of death or disability (mRS 2–6, OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.85–1.19; p = 0.958) between Asian and non-Asian patients (Table 3). Major disability (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.80–1.13; p = 0.572) and death (OR 1.25, 95% CI 0.95–1.65; p = 0.116) were also comparable, but Asian patients had higher odds of any ICH (OR 1.51, 95% CI 1.23–1.86; p = 0.0001). Neurological deterioration was also higher in Asians within 24 h (OR 1.58, 95% CI 1.18–2.12; p = 0.002) and 3 days (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.05–1.71; p = 0.019), despite comparable symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage according to the second European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS2) criteria between Asians and non-Asians (35.4 vs. 34%; online suppl. Table 2).

Discussion

In our post hoc analyzes of the ENCHANTED trial, we have shown wide-ranging differences in the characteristics, management, and outcomes between Asian and non-Asian thrombolyzed AIS patients. Despite Asian patients being younger and less cardiovascular risk factors, they had higher odds of ICH and early neurological deterioration, although this did not translate into worse functional outcomes compared to non-Asian patients. There was no apparent interaction of differences in early management, including use of evidence- and non-evidence-based care, on outcomes.

The lower age of Asian AIS patients, by almost a decade, compared to patients in other regions, is well recognized [-]. Potential explanations for this age disparity include poor blood pressure control, high levels of smoking, and dietary factors in particular high salt intake [, ], which all cause endothelial damage and accelerate development of atheroma and thrombus [-]. Our study also reinforces the need for improved management of cardiovascular risk factors in Asians, where their less likelihood of receiving treatment for hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hypercholesterolemia calls for greater awareness, detection, and intensity of management in the community.

In regard to the patterns of stroke care, our study highlights several differences in the manner in which AIS patients are managed compared to those in other regions, in particular with regard to rehabilitation, where they are less likely to receive early mobilization by a therapist and input from other members of modern multidisciplinary rehabilitation team. This has been noted by other studies in China [], suggesting that up to two-thirds of stroke patients do not receive any formal in-hospital rehabilitation, even though early rehabilitation is also recommended in Chinese guidelines [], perhaps reflecting insufficient discipline expertise and/or beliefs and approaches to promoting recovery from disabling illnesses. It is possible the risk of complications, such as pneumonia, venous thromboembolism, and pressure sores [], may be influenced by limited access to early “active” rehabilitation, as recommended by guidelines []. However, despite Asian patients having lower admission to acute stroke unit and delays in receipt of intravenous thrombolysis compare to other patients, they had higher utilization of intensive care and lower use of withdrawal of care directives, which provides a different perspective on the manner of active care for AIS by region. In AIS guidelines outside of Asia [], withdrawal of active care is often applied to patients with severe brain injury, but this is not referenced in Chinese guidelines where any such decision is strongly influenced by family beliefs and Chinese culture. Given the proven benefits of thrombolysis specialized stroke unit care, consistently recommended in both Asian and non-Asian guidelines [, ], continued efforts are needed to improve their access and thus patient outcomes from AIS in Asia.

The higher odds of early neurological deterioration in Asian AIS patients may reflect their greater frequency of intracranial atherosclerosis, where progressive symptom onset and early neurological deterioration have been noted to be more common than in cardiogenic embolism []. Regional differences in clinical practice and ethnic disparities are other potential reasons. Taken together with the higher odds of ICH after thrombolysis in Asians, it is reassuring to note that this did not translate into effects on overall functional outcome. An international registry [] has shown similar frequencies of symptomatic ICH between Asians and Europeans, but higher functional independence (mRS scores 0–2) in patients from several Asian countries. Conversely, several other studies have shown mixed associations of functional outcomes from AIS in Asia [, ]. There are, however, difficulties in making comparisons across studies who have used different selection criteria and definitions.

Strengths of our study include the large clinical population with systematic and complete data from a wide range of health-care settings. However, we acknowledge a certain degree of selection bias because of these data are from a clinical trial, where over half of Asian participants were from China. We also lacked information on a range of socioeconomic, clinical, and management factors, which can influence outcomes and being an observational analysis, there is likely to have been incomplete adjustment for confounding factors, measured and unmeasured. Finally, being post hoc with multiple comparisons, the results have the potential for random error.

In summary, we have shown that Asian patients have a wide range of characteristics including age, risk factor profile, and management, both of intravenous alteplase dose and ancillary care, than non-Asians patients who receive thrombolysis for AIS. Moreover, despite their greater risk of early neurological deterioration and ICH, the chance of good functional recovery is comparable between Asians and non-Asians. Despite the high use of active care measures, reflected by high use of intensive care and low use of withdrawal of care directives, there are opportunities to further enhance stroke outcomes in Asia through increased efficiencies in the delivery of accorded stroke care and delivery of thrombolysis treatment in many parts of Asia. Similarly, the profile of Asian AIS patients indicates the need for policy makers and services to intensify efforts at screening and control of cardiovascular risk factors, for both primary and secondary prevention of stroke.

Statement of Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee at each participating hospital center, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient or an appropriate surrogate. Protocol No. X11-0123 & HREC/11/RPAH/176 approved by Australia Royal Prince Alfred Hospital HREC.

Conflict of Interest Statement

L.S., H.A., and C.S.A. report speaking fees from Takeda China. T.R. is a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Senior Investigator; the views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or Department of Health and Social Care. J.C. reports grants from Servier and NHMRC. C.S.A. holds a Senior Investigator Fellowship and grants from NHMRC and Takeda China. X.W. is supported by National Heart Foundation postdoctoral fellowship (102117); New South Wales Health commission investigator development grant; and NHMRC investigator grant (APP1195237). Other authors have no relevant disclosures.

Funding Sources

Funding was primarily from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia. Additional funding was from the Stroke Association of the United Kingdom, the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development of Brazil, and the Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family Affairs of the Republic of Korea (HI14C1985).

Author Contributions

C.S.A., L.S., and G.L. contributed to study design, organization, statistical review, and critique of the report; C.C. drafted the manuscript; and X.W. undertook analyses. All the authors contributed to the concept and rationale for the study, made critical revisions, approved the final article, and take responsibility for its content and integrity.

References

- 1. Howard VJ, Cushman M, Pulley L, Gomez CR, Go RC, Prineas RJ, et al. The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25:135–43.http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000086678.

- 2. Wasay M, Khatri IA, Kaul S. Stroke in South Asian countries. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:135–43.http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2014.13.

- 3. Khan NA, McAlister FA, Pilote L, Palepu A, Quan H, Hill MD, et al. Temporal trends in stroke incidence in South Asian, Chinese and white patients: a population based analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0175556.http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175556.

- 4. Wong KS. Risk factors for early death in acute ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage: a prospective hospital-based study in Asia. Asian Acute Stroke Advisory Panel. Stroke. 1999;30:2326–30.http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.str.30.11.2326.

- 5. Banerjee S, Biram R, Chataway J, Ames D. South Asian strokes: lessons from the St Mary’s stroke database. QJM. 2010;103:17–21.http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcp148.

- 6. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker T, et al. 2018 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018;49:e46–e110.

- 7. Emberson J, Lees KR, Lyden P, Blackwell L, Albers G, Bluhmki E, et al. Effect of treatment delay, age, and stroke severity on the effects of intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;384:1929–35.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60584-5.

- 8. Huang Y, Sharma VK, Robinson T, Lindley RI, Chen X, Kim JS, et al. Rationale, design, and progress of the ENhanced control of hypertension ANd Thrombolysis strokE stuDy (ENCHANTED) trial: an international multicenter 2 x 2 quasi-factorial randomized controlled trial of low- vs. standard-dose rt-PA and early intensive vs. guideline-recommended blood pressure lowering in patients with acute ischaemic stroke eligible for thrombolysis treatment. Int J Stroke. 2015;10:778–88.

- 9. Anderson CS, Woodward M, Arima H, Chen X, Lindley RI, Wang X, et al. Statistical analysis plan for evaluating low- vs. standard-dose alteplase in the ENhanced Control of Hypertension and Thrombolysis strokE stuDy (ENCHANTED). Int J Stroke. 2015;10:1313–5.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ijs.12602.

- 10. Anderson CS, Woodward M, Arima H, Chen X, Lindley RI, Wang X, et al. Statistical analysis plan for evaluating different intensities of blood pressure control in the ENhanced control of hypertension and thrombolysis strokE stuDy. Int J Stroke. 2018;14:555–8.

- 11. Anderson CS, Robinson T, Lindley RI, Arima H, Lavados PM, Lee TH, et al. Low-dose versus standard-dose intravenous Alteplase in acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2313–23.http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1515510.

- 12. Anderson CS, Huang Y, Lindley RI, Chen X, Arima H, Chen G, et al. Intensive blood pressure reduction with intravenous thrombolysis therapy for acute ischaemic stroke (ENCHANTED): an international, randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoint, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393:877–88.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30038-8.

- 13. Mozaffarian D, Fahimi S, Singh GM, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Engell RE, et al. Global sodium consumption and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:624–34.http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1304127.

- 14. Powles J, Fahimi S, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Shi P, Ezzati M, et al. Global, regional and national sodium intakes in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis of 24 h urinary sodium excretion and dietary surveys worldwide. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003733.http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003733.

- 15. Qian Y, Ye D, Wu DJ, Feng C, Zeng Z, Ye L, et al. Role of cigarette smoking in the development of ischemic stroke and its subtypes: a Mendelian randomization study. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:725–31.http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S215933.

- 16. Ji R, Pan Y, Yan H, Zhang R, Liu G, Wang P, et al. Current smoking is associated with extracranial carotid atherosclerotic stenosis but not with intracranial large artery disease. BMC Neurol. 2017;17:120.http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12883-017-0873-7.

- 17. Larsson SC, Burgess S, Michaëlsson K. Smoking and stroke: a mendelian randomization study. Ann Neurol. 2019;86:468–71.http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ana.25534.

- 18. Wu S, Wu B, Liu M, Chen Z, Wang W, Anderson CS, et al. Stroke in China: advances and challenges in epidemiology, prevention, and management. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:394–405.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30500-3.

- 19. Neurological Rehabilitation Group of the Chinese Society of Neurology of the Chinese Medical Association. Chinese guidelines for stroke rehabilitation (Full version 2011) (Chinese). Chin J Rehabil Theor Pract. 2011;18:301–18.

- 20. Langhorne P. Measures to improve recovery in the acute phase of stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1999;9(Suppl 5):2–5.http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000047570.

- 21. Holloway RG, Arnold RM, Creutzfeldt CJ, Lewis EF, Lutz BJ, McCann RM, et al. Palliative and end-of-life care in stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:1887–916.http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/STR.0000000000000015.

- 22. National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions (UK). Stroke: National Clinical Guideline for Diagnosis and Initial Management of Acute Stroke and Transient Ischaemic Attack (TIA). London: Royal College of Physicians; 2008.

- 23. Cerebrovascular Epidemiology Group of the Chinese Society of Neurology of the Chinese Medical Association. Chinese guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of acute ischemic stroke 2010 (Chinese). Chin J Neurol. 2010;43:146–53.

- 24. Yu WM, Abdul-Rahim AH, Cameron AC, Kõrv J, Sevcik P, Toni D, et al. The incidence and associated factors of early neurological deterioration after thrombolysis: results from SITS registry. Stroke. 2020;51:2705–14.http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.028287.

- 25. Rha JH, Shrivastava VP, Wang Y, Lee KE, Ahmed N, Bluhmki E, et al. Thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke with alteplase in an Asian population: results of the multicenter, multinational Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-Non-European Union World (SITS-NEW). Int J Stroke. 2014;9(Suppl A100):93–101.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00895.x.

- 26. Sharma VK, Ng KW, Venketasubramanian N, Saqqur M, Teoh HL, Kaul S, et al. Current status of intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke in Asia. Int J Stroke. 2011;6:523–30.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4949.2011.00671.x.

Gang Li and Lili Song contributed equally to this manuscript.