Did you ever wait for people to show up at an appointment, and gave up hope that they would arrive, left, and found out that the others actually showed up, but far past the time of the appointment? A Dutch woman experienced this in Argentina. Or, were you ever caught off guard when you said “We should meet again some time!” and the person pulled a pocket diary from her bag to write down the appointment? A Peruvian man once told one of us that this happened to him when he started living in the Netherlands. The meeting times for appointments and what lateness means appear to differ in different parts in the world. Lateness indicates a point in time after a designated time for an appointment or event, and is the opposite of punctuality (). When is lateness reasonable, acceptable, and excusable? At what point does lateness become unacceptable and are norms violated?

The answer to these questions may not be the same everywhere in the world. Sociocultural differences have been shown to relate to lateness to appointments and meetings (). Experiences abroad with regard to appointments can be bewildering (; ), because the implicit rules, or norms, may not be apparent to outsiders. Lateness is considered inappropriate in many situations, but less so in others. The rules regarding lateness may be implicit and fuzzy, and may comprise social norms, and more specifically, cultural norms ().

In this study, we aim to contribute to the research on cultural temporal norms by studying lateness to business meetings and appointments. Time is a major structuring factor within the world of work and business, regulated by scheduling of milestones and deadlines. Lateness is important in terms of outcomes such as productivity, optimal scheduling, and synchronization in projects (cf. ), and abiding by different norms may affect relations and cooperation (). Lateness in meetings has been shown to affect problem-solving negatively (). Research on cultural differences in lateness is scarce. In answering call for theoretical and empirical integration of the divergent temporal dimensions used in cross-cultural research on time so far, we compare lateness in event-based and clock-time cultures (). Second, we combine this approach with one of the determinants of lateness: the status of the target person to be met in an appointment. We test whether cultural differences in power distance affect the acceptability of lateness in meeting high status persons.

Theoretical Background

Lateness may be seen as the opposite of punctuality, where being punctual implies that no time norm is violated, and lateness implies that the time norm is violated (). Lateness may be considered a violation of an expectancy (), and it is one of those seemingly minor behaviors, similar to body language or speech rhythms, that vary systematically between cultures and that may potentially lead to distrust in cooperation (). Lateness is a nonverbal behavior informative of time norms, similar to how the speed of walking or communicating is informative about the pace at which life is lived (). Many nonverbal behaviors reveal meaning about how time is perceived, interpreted, and used by a person or in a culture (; ; ). Different interpretations of time and lateness may result in different objective time intervals deemed acceptable in particular situations. Individuals vary widely in what they personally find acceptable, irrespective of their (sub)culture (). As such, these interpretations may be seen as implicit fuzzy rules that govern social behavior, or norms (). Temporal norms play an important role in international work teams () and in how negotiations are conducted (; ; ).

Factors associated with lateness to work in general may be broadly categorized as personality and individual difference factors, attitudes, and context (; ; ). Norms regarding time between cultures were examined by . They investigated so-called “On-Time Windows,” intervals around a specific point in time. Individuals with larger On-Time Windows scores have wider, more flexible intervals for what counts as “on time.” These windows tend to be asymmetrical, with a longer time frame before the time point than after it, where arriving early implies less normative consequences than arriving late. concluded that On-Time Windows were largely unrelated to personality, temporal orientation, social class, and other personal characteristics, but highly related to the level of development of different cultural groups. Larger intervals of lateness were found to be acceptable in less developed societies, as identified by the United Nations’ Human Development Index (). also pointed out that norms regarding achievement and busyness as a virtue may be more prominent in some cultures than in others. One way to distinguish how lateness is perceived in different cultures is to focus on whether time in a culture is seen as clock time or event time (; ).

Clock Time

A culture may be characterized by having clock time or event time. In clock time cultures, activities are scheduled and determined by the clock (“It is 6 o’clock, it is time to eat”). These cultures have also been referred to as monochronic cultures (), in which one activity is scheduled after another. The Western world, broadly speaking, is characterized by clock. Time is a resource, something that is fixed, as if it were material: “we earn it, spend it, save it, waste it” (, p. 7). Anglo-Saxon cultures, Protestant countries, and individualistic cultures emphasize that time should be used wisely, whereas this may not be emphasized in other cultures (). The accuracy of clocks was indicative of a faster pace of life (). Business and achievement are likely to be more important than social considerations in a clock time culture (). Pace of life was related to climate, an economic index based on the level of income, and to collectivism (). One illustrative example regarding lateness specifically comes from Germany, where “arriving too late” appears as number 6 in the list of top 10 of topics people dream about most frequently ().

Event Time

In contrast, event time cultures depend on how social events shape the beginning, duration, and ending of activities (“Now that we met in the street, let’s eat”). This type of culture may be seen as polychronic, in which people use time less purposefully than monochronic, with frequent switching between activities, and combining social and work activities. In particular, social obligations and maintaining relations without offending anyone weigh heavily () and coming across as friendly, rather than professional and efficient, is important (). Although the clock is used, a more elastic idea of time use is present than in clock time cultures. showed that present-fatalistic scores were correlated with the width of On-Time windows. The present-fatalistic time perspective, and more specifically the concept of Insha’Allah in Islamic countries, indicates that individuals do not necessarily consider themselves in control of events or actions. When people are asked if something will happen, they may answer Insha’Allah (if Allah wills), which means that fate will decide. It can mean yes or no, or anything in between, such as probably, possibly, hopefully, or perhaps.

Lateness to Meetings

Lateness to meetings in the United States and Europe was found to be highly consequential to individuals, groups, and organizations, as it affects both satisfaction with, stress associated with, and effectiveness of the meetings (; ; ). Expectations and norms about business meetings in general differ across cultures. A review of the literature () showed, for example, that meetings in the United Kingdom take much longer than in other nations. concluded the same and showed that both meeting duration and punctuality may differ between cultural clusters. Late starts and late endings also appeared more frequently in meetings conducted in Turkey in comparison to other countries (). In the Gulf States, a flexible approach to time in meetings is used (). Given the importance of lateness to meetings in Western settings, but the limited knowledge about non-Western settings, there is a need to find out more about lateness to meetings in different cultures. Clock and event time cultures are likely to play a role in defining lateness to meetings. Languages and their cultural embedding are important in shaping time perceptions (). For example, e-mail communication may be analyzed to extract cultural clues. found marked differences in preferences in e-mail communication of professionals, where persons in monochronic (clock time) cultures prefer more prompt, precise, task-related, but also less formal and less relationship-oriented e-mail messages than those characterized as belonging to a polychronic (event time) culture. We expect similar differences to emerge when employees are asked to define what they mean by lateness to meetings in their own words. Thus, we posit the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a: In a clock time culture, people describe lateness to meetings more frequently in terms of specific time intervals that need to be adhered to than in an event time culture.

Hypothesis 1b: In an event time culture, people describe lateness to meetings more frequently with reference to other people or an event than in a clock time culture.

In addition, when asked for specific times of when lateness to appointments with a single person in a work-related context is still acceptable, we expect, similar to what concluded about the sociocultural nature of punctuality, that the intervals will be more generous in an event time culture than in a clock time culture.

Hypothesis 2: In an event time culture, larger time frames of lateness to a work appointment are acceptable than in a clock time culture.

Status and Lateness

Waiting for those in higher status to arrive may be more acceptable in some cultures than in others. expressed it as Rule 4 of his book on the geography of time: “Status dictates who waits.” However, status differences may be less important in certain cultures, as research showed regarding the power distance dimension of culture. Power distance is defined as the extent to which people expect and accept that power is distributed unequally; national power distance refers to how societies cope with human inequality and status differences. Power distance and the human development index were highly inversely correlated in previous research (). It may expected that the more egalitarian (characterized by lower power distance) a society is, the less it should matter what a person’s status is; the norms should apply to everyone in the same way. measured waiting time as a function of status. They asked students and professors how long they would wait for a professor or a student who was late for an appointment. All said they would wait longer for a professor than for a student. who aimed to replicate this finding 30 years later, did not find this difference, perhaps because they used the word “teacher” rather than professor. However, still found a status effect for other roles (government worker meeting government official): the higher the status of the person to meet, the more acceptable it was that this person was late for an appointment. Larger power distance is likely to be a feature of event time culture (cf. ). We thus pose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: The difference in lateness norm in waiting for a high status versus a low status person is lower in a clock time culture than in an event time culture.

The Current Study

The current study has two main goals. First, to test whether there were differences in definitions of respondents in clock versus event cultures about lateness to work meetings. Second, to test whether respondents from clock versus event cultures differ in the acceptability of lateness to work-related appointments when individuals have different social status. We compared three cultural groups: Pakistani respondents as representative of event time–based culture, partly based on its Islamic background, and South African and Dutch respondents as representative of a clock time cultures. We furthermore make this group distinction on the basis of the Human Development Index (HDI), as an economic index (cf. ) that also encompasses other societal development such as education and health care. followed up study and measured walking speed in 31 countries. We correlated these data with HDI in 2006 and found they were inversely correlated (r = –.57) and as such provided some information on the use of time within countries with different development levels. More recent information on the three groups in our study showed that the HDIs in 2018 (http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/) were Pakistan 0.562, South Africa 0.699, and the Netherlands 0.931. Although the South African index does not appear to be representative of a developed (clock time) culture, we still consider the respondents as such because almost all belong to the group of descendants of English and Dutch who describe themselves as “White” in South Africa. It is representative of the Anglo-Saxon cultural cluster, as previous research showed (). In addition, within the distinction between clock and event time, we considered power distance for the events related to status. Even within clock time culture, there may be differences regarding status, but we expect these to be smaller than in event time cultures. As for the three groups in the study, the Dutch respondents are representative of a low power distance culture, as the Netherlands ranked as one of the lowest of 21 nations on power distance (). Pakistani respondents were seen as representing a high power distance culture (55 in vs. Netherlands 38). The South African respondents would rank in between, being representative of clock time culture but still relatively high on power distance (49 in ).

Method

Sample and Procedure

We set out to study two time-related phenomena in three cultural groups using a questionnaire. The sample consisted of 78 South African (85% were self-described as “White,” 15% Other), which would indicate they are closer to Anglo-Saxon cultures; 83 Pakistani; and 86 Dutch respondents, obtained through a combination of self-selection sampling and snowball sampling. The questionnaire, requesting participation in a study on “International Management and Time Perception,” was distributed via e-mail and social media (Facebook and Twitter). The South African and Dutch respondents were recruited by a student in his Master’s thesis project. The respondents in Pakistan were recruited through a researcher at a university. Both researchers used their personal networks to involve respondents. Male and female respondents were more or less equally represented. The average age of the sample was 31 (SD = 12) years. The respondents were managers (35.2%), or academically trained professionals (or equivalent) non-managers (30%). The other respondents had vocationally trained jobs (17.8%) or were unskilled/semi-skilled, or had no job, including full-time students (17%). The number of years in education was 13.65 on average (SD = 4.37). As such, the respondents within the three groups were highly educated and young employees.

Measures

Lateness to meetings

Respondents replied in an open-ended format to the question “Think about a time you considered yourself or someone else to be late to a meeting. Now, describe why in your mind you classified it as lateness” ().

Endorsement of meeting lateness definitions

Eight scenarios were presented to the respondents (, p. 328). They systematically varied according to three factors, one temporal factor (on time or late) and two social-contextual factors (group started or not / members had / had not arrived) (see Supplemental Appendix 1). Scenarios 5 and 6 mentioned that the group had already started on the agenda items. After reading each scenario, participants answered the following yes/no question: “Is this lateness to a meeting?”

Lateness for appointments

This measure consists of four scenarios (; ), also used by . The scenarios contain a short description of people meeting others in different roles. The respondents were asked to indicate the time at which a person arriving would be inappropriately late (see Supplemental Appendix 2). Respondents were asked what they found inappropriately late in these circumstances, in minutes. The difference in minutes from the meeting time was taken as the lateness measure.

Control variables

The South African respondents were on average about 7 years older than the other two groups. We included age, education, and gender as demographic variables in the overall comparisons between the groups because these played a role in previous research on lateness.

Results

Lateness to Meetings

In order to test Hypotheses 1a and 1b, we analyzed the data in three steps. We analyzed the open answers provided in reaction to the statement “Think about a time you considered yourself or someone else to be late to a meeting. Now, describe why in your mind you classified it as lateness” in two ways. First, we did a simple count of the words appearing in the answers, and we included all words that were used more than four times, using an online word cloud application (www.woordwolk.nl). “Time,” “minutes,” and “person” were mentioned more or less equally in all three groups. This first step in the analysis did not provide direct support for Hypotheses 1a and 1b. However, upon further inspection, we noted that the most frequently used word in the Dutch sample was not “time,” as in the other samples, but “agreed” (afgesproken). In addition, the word “agreement” (afspraak) also appeared as one of the other frequently mentioned words in the Dutch sample. “Agreed” was also found in the set of most frequently used words of the South African respondents. However, the Pakistani respondents did not use the word “agreed” at all, but here “traffic” appeared in the list. In Supplemental Appendix 3, the three visualizations and the frequency of the words are provided.

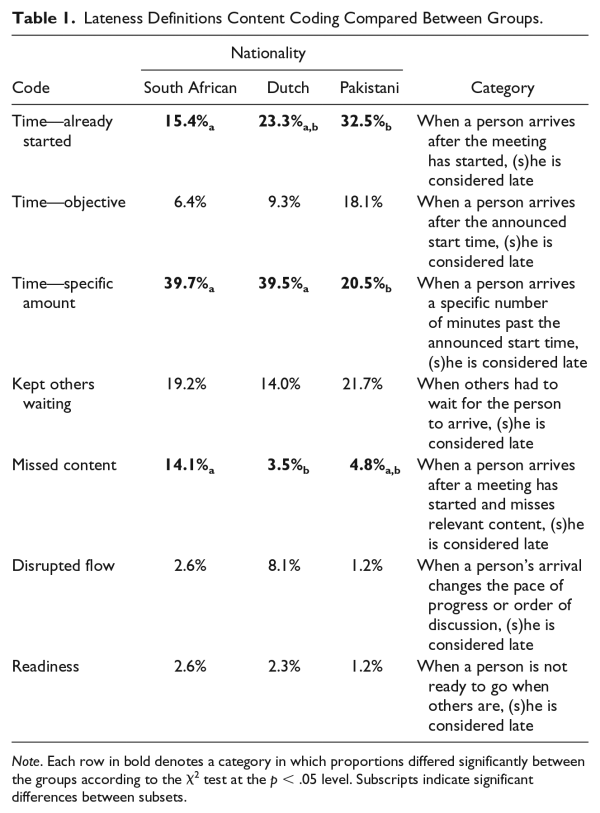

In the second step, we thematically coded the answers. We followed ’s thematic coding scheme (see Table 1). There was substantial inter-rater agreement on the seven categories of the two authors on the English answers (Cohen’s kappa = .68). We took this as sufficient support to use the first rater’s coding of the answers in Dutch. Table 1 shows the proportions of the categories across the groups. These were significantly different, χ2 (12,247) = 31.25, p < .001. Specifically, three themes differed significantly. In line with Hypothesis 1b, whether the meeting started (event) “Time—already started” was mentioned by the Pakistani respondents more frequently—although they were not significantly different from the Dutch respondents, only from the South African. Also, the category “Time—specific amount” differed between the groups; the Pakistani group referred less to a specific number of minutes in their answers than the other two groups, in line with Hypothesis 1a. A third difference between the groups emerged that had not been hypothesized: the South African respondents referred to missed content more often than the other two groups. A comparison with ’s study among American respondents revealed that respondents in the current study referred to keeping others waiting more frequently (over 14%) than in the previous study (6%). Apart from these three differences, the overall analysis shows many similarities between the cultural groups.

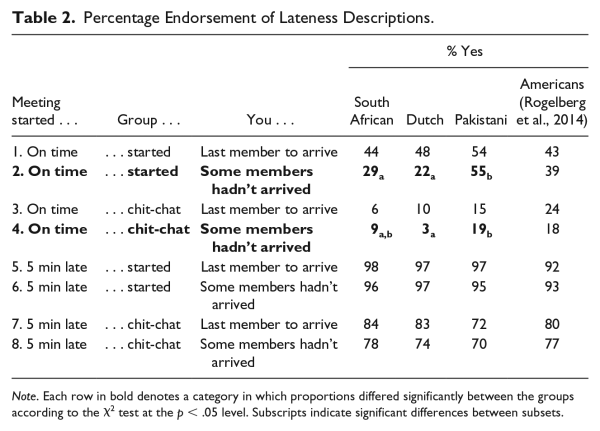

The third step in testing Hypotheses 1a and 1b consisted of comparing the endorsement of eight scenarios as examples of meeting lateness (See Supplemental Appendix 1) with yes or no. The groups differed on two of the eight descriptions provided (see Table 2), reinforcing the idea that only small differences exist between the groups. Regarding the scenario “When you arrived at the scheduled start time for the meeting, the group had already started working on the agenda items. One or more of your other group members had not arrived when you got there,” Pakistani respondents qualified it as late more often than the other two groups (55% vs. Dutch 22% and South Africans 29%, χ2 [2,247] = 22.33, p < .001). Pakistani respondents also endorsed “When you arrived at the scheduled start time for the meeting, people were chit-chatting with one another. One or more of your other group members had not arrived when you showed up.” more frequently (19.3% vs. Dutch 3% and South Africans 9%, χ2 [2,247] = 11.47, p < .003). These two responses showed that the Pakistani respondents paid more attention to the fact that some members had not arrived. The Dutch respondents, however, found this unimportant, whereas the responses of the South African respondents were similar to both other groups. The findings of this analysis are not in line with Hypotheses 1a and 1b, because all groups paid attention to starting on time, but reacted differently in relation to the arrival of other members. Pakistani respondents on members who had not arrived yet when they were not the last to arrive. Comparing these numbers to the previous research by shows that Americans were also more inclined than the Dutch or South African to say that lateness depended on the other members being late when they themselves were not the last one to arrive (39% and 18% for Scenarios 2 and 4, respectively).

Lateness to Appointments

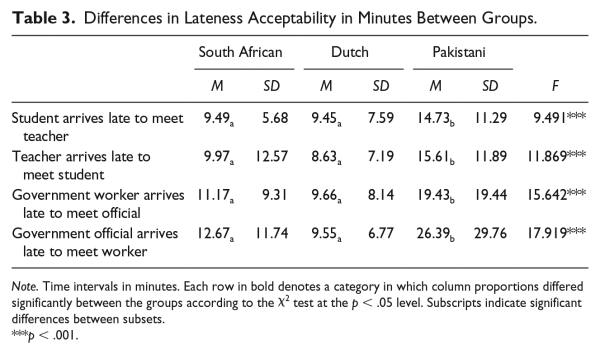

Hypothesis 2 stated that larger time frames of lateness would be acceptable in an event time culture than in a clock time culture. We analyzed the acceptability of lateness for each scenario in which the respondent is asked to imagine meeting a particular person (see Supplemental Appendix 2). The multiple analysis of variance (4 ×3) showed an effect of nationality on total average lateness, F(2,230) = 18.10, p < .001, with the control variables having nonsignificant effects except gender, F(2,230) = 3.94, p < .05, indicating that women provided larger intervals than men. In line with Hypothesis 2, Pakistani were more accepting of lateness overall (m = 19.04) than South African (m = 10.83) and Dutch (m = 9.32) respondents. South African and Dutch respondents did not differ. Table 3 shows the averages for each scenario.

To test Hypothesis 3, we compared the time intervals within the national groups for the different statuses of the roles in the scenarios. Similar to , we conducted paired t-tests to establish whether respondents make a distinction between the roles in the scenarios, and transformed these to effect sizes d for comparison. None of the groups made a distinction between a student meeting a teacher and a teacher meeting a student. However, there were differences between the worker meeting the government official versus the official meeting the government worker, as may be seen in Table 3, where there was a difference in the number of minutes between Scenarios 3 and 4 for the South African and Pakistani respondents. The Dutch respondents did not make a distinction between the different roles in the scenarios (d = .02), in contrast to the South African (d = .14) and Pakistani respondents (d = .25). This finding was only partially in line with Hypothesis 3 because South African respondents made the status distinction even though they may be considered to adhere to clock time.

Discussion

Summary of Findings

Our study on clock time and event time in relation to lateness showed some differences between the cultural groups. When respondents were asked how they defined lateness to meetings, they used different words: whereas all groups referred to time, only the Dutch and South African respondents used the word “agreement.” A further content analysis of the answers revealed some differences, notably between whether the actual start of the meeting was taken as a reference point (more event focused) was more often mentioned by the Pakistani and Dutch respondents, but a specific number of minutes mentioned more often by Dutch and South African respondents (clock time). The endorsement of definitions on lateness provides some difference on how people in event-based cultures may consider themselves late, not on the basis of the starting time of the meeting, and their own arrival, but based upon whether all members had arrived. This would imply that there may be two foci of comparison in addition to the clock time: to those who started, as the Dutch and South African respondents did, versus those who had not arrived yet as the Pakistani did. Thus, overall, our hypotheses on the influence of clock time and event time in definitions of lateness to meetings are only partially supported; subtle differences but also similarities appeared between the groups.

In line with Hypothesis 2, we found that Pakistani provided larger time intervals for acceptable lateness than the Dutch and South African respondents, on average two to three times longer. With regard to our third hypothesis on the role of status, none of the groups, similar to what found, made a distinction between a student meeting a teacher and a teacher meeting a student. However, for the government official meeting a government worker versus a government work meeting a government official, the Dutch respondents did not make this distinction, whereas the other two groups did. This finding fits with the egalitarian values of the Dutch. However, South African respondents (and Estonian respondents in ) are considered as representative of clock time cultures, but nevertheless made the distinction. However, in comparison to Pakistani (and Moroccan in respondents from event time cultures made an even larger distinction. Thus, for the specific case of lateness in which waiting for higher status persons is involved, event time culture is a likely explanation, but even within clock time cultures, power distance may explain why there are different time norms.

Theoretical Implications

Our study contributes to a more refined idea of lateness in a cross-cultural perspective. Whereas previous studies have mentioned clock time and event time culture (), not many empirical studies have been published on it, nor was lateness explicitly linked to it. Our finding regarding the use of the word “agreement” may be seen as an extension of a Protestant Work Ethic’s idea of “a deal is a deal,” a universalistic value (cf. , pp. 29-48): promising something means an obligation. On the contrary, in so-called particularistic cultures, the nature of relationships may be more important than a deal. Thus, the answers may imply that the dimensions universalism–particularism are important to the distinction between clock time and event time cultures. Furthermore, the differences between the cultural groups are not as straightforward as only a general tolerance for longer time intervals in being late. The Pakistani respondents were not necessarily more accepting of lateness in all situations. For example, they were stricter about their own lateness to meetings when others had not arrived yet. This provides another clue perhaps on what particularism means in this setting. In addition, the differences in status in waiting times provided additional information to how clock time and event time are further shaped by power distance.

Practical Implications

If people have control over the behavior and are rewarded for the desired behavior, lateness can be managed (). However, this may be more difficult in countries with lower development because of the basic conditions needed for punctuality. People may be more accepting that lateness may occur due to factors outside a person’s control, reflecting the fatalistic attitudes about time. An agreement or promise may not mean the same thing if it is unclear if an individual cannot be personally responsible. The awareness of these differences between societies may help in intercultural cooperation.

Limitations and Future Research

The present study refined some of our knowledge in a relatively under-researched area, but it also has some limitations. The sample was relatively small, with limited statistical power. We assumed that our sampled groups were somehow representative of these cultural differences in the respective countries, but they were not randomly drawn in each country. We do not claim in any way that the samples were representative of the whole country from which the respondents were recruited. The nature of the recruitment was such that a relatively young and highly educated group of employees was included. As such, the sample may represent such groups within the society at best. Furthermore, although the level of development of a society may be a good indicator, clock time and event time cultures were not assessed directly. Future research should focus on validating measures to indicate what defines such cultures in more detail. In particular, future studies should focus on a more refined assessment of the control versus fatalistic attitude people may have, not only on time but also of the context, particularly in relation to the institutions within a society. Future research may focus on one of the explanations that has received less research attention with regard to lateness, the institutional context that affects the sociocultural norms (; ). If individuals cannot depend on the context being conducive to arriving on time, for example, because traffic is chaotic (see some of the replies in the sample of Pakistani respondents), individuals are not in control over the outcomes of the behavior. In other words, control as a predictor of lateness has been neglected, although it is an important one, proposed in the theory of planned behavior (). Reliable institutions may help to establish routines. “Entropy,” or irregularity of intervals in sending out Twitter messages, was negatively related to pace of life (). Without the support of institutions that may help people to be punctual, norms may be plied to accommodate lateness to business meetings and appointments. Another suggestion for future research on lateness and information exchange in work settings is the theoretical framework of . They suggest taking an interactional perspective: employees appraise and experience lateness depending upon the institutional context, organizational climate, coworkers, their status, and their behavior.

In conclusion, our research showed that lateness norms differed within three cultural groups, but not entirely as anticipated. Clock time cultures may be inclined to consider lateness more as a violation of an agreement than event time cultures do. Typical for event time culture, Pakistani respondents defined lateness to meetings less as an agreement, more tied to the group rather than the scheduled time, and did not tie to a specific number of minutes, and provided more leeway for lateness. The status of the person waiting in an appointment was important to both clock time and event time respondents, except for the Dutch respondents who may have been extremely egalitarian in this regard.

The authors thank Patrick Voskuilen for his assistance with data collection and Jan Francis-Smythe and Robert Levine for their comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Adams S. J., Van Eerde W. (2010). Time use in Spain: Is polychronicity a cultural phenomenon? Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25, 764–776.

- Allen J. A., Lehmann-Willenbrock N., Landowski N. A. (2014). Linking pre-meeting communication to meeting effectiveness. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 29, 1064–1081.

- Allen J. A., Lehmann-Willenbrock N., Rogelberg S. G. (2018). Let’s get this meeting started: Meeting lateness and actual meeting outcomes. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(8), 1008–1021.

- Alon I., Brett J. M. (2007). Perceptions of time and their impact on negotiations in the Arabic-speaking Islamic world. Negotiation Journal, 23, 55–73.

- Arman G., Adair C. K. (2012). Cross-cultural differences in perception of time: Implications for multinational teams. European Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology, 21, 657–680.

- Atwater L., Wang M., Smither J. W., Fleenor J. W. (2009). Are cultural characteristics associated with the relationship between self and others’ ratings of leadership? Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 876–886.

- Basabe N., Ros M. (2005). Cultural dimensions and social behavior correlates: Individualism-collectivism and power distance. International Review of Social Psychology, 18, 189–225.

- Blount S., Janicik G. A. (2001). When plans change: Examining how people evaluate timing changes in work organizations. Academy of Management Review, 26, 566–585.

- Brislin R. W., Kim E. S. (2003). Cultural diversity in people’s understanding and uses of time. Applied Psychology, 52, 363–382.

- Clark K., Peters S. A., Tomlinson M. (2005). The determinants of lateness: Evidence from British workers. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 52, 282–304.

- Dishon-Berkovits M., Koslowsky M. (2002). Determinants of employee punctuality. The Journal of Social Psychology, 142, 723–739.

- Fulmer C. A., Crosby B., Gelfand M. J. (2014). Cross-cultural perspectives on time. In Shipp J. A., Fried Y. (Eds.), Time and work, volume 2, how time impacts groups, organizations and methodological choices (pp. 53–75). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Gelfand M. J., Jackson J. C. (2016). From one mind to many: The emerging science of cultural norms. Current Opinion in Psychology, 8, 175–181.

- Guenter H., Van Emmerik I., Schreurs B. (2014). The negative effects of delays in information exchange: Looking at workplace relationships from an affective events perspective. Human Resource Management Review, 24, 283–298. doi:

- Gupta V., Hanges P. J., Dorfman P. (2002). Cultural clusters: Methodology and findings. Journal of World Business, 37, 11–15.

- Hall E. T. (1959). The silent language. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

- Hall E. T. (1960). The silent language in overseas business. Harvard Business Review, 38(3), 87–96.

- Halpern J., Isaacs K. (1980). Waiting and its relation to status. Psychological Reports, 46, 351–354.

- Hofstede G. H. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Holtbrügge D., Weldon A., Rogers H. (2013). Cultural determinants of email communication styles. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 13(1), 89–110.

- Jones J. M. (1988). Cultural differences in temporal perspectives: Instrumental and expressive behaviors in time.

- Kemp L. J., Williams P. (2013). In their own time and space: Meeting behaviour in the Gulf Arab workplace. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 13(2), 215–235.

- Köhler T., Gölz M. (2015). Meetings across cultures: Cultural differences in meeting expectations and processes. In The Cambridge handbook of meeting science (pp. 119–149). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Koslowsky M. (2000). A new perspective on employee lateness. Applied Psychology, 49, 390–407.

- Koslowsky M., Sagie A., Krausz M., Singer A. D. (1997). Correlates of employee lateness: Some theoretical considerations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 79–88.

- Lehmann-Willenbrock N., Allen J. A. (2017). Well, now what do we do? Wait. . . A group process analysis of meeting lateness. International Journal of Business Communication. 10.1177/2329488417696725

- Levine R. V. (2005). A geography of busyness. Social Research: An International Quarterly, 72, 355–370.

- Levine R. V. (2008). A geography of time: On tempo, culture, and the pace of life. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Levine R. V., Norenzayan A. (1999). The pace of life in 31 countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30, 178–205.

- Levine R. V., West L. J., Reis H. T. (1980). Perceptions of time and punctuality in the united states and brazil. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 541–550.

- Li J., Xin K. R., Tsui A., Hambrick D. C. (1999). Building effective international joint venture leadership teams in China. Journal of World Business, 34(1), 52–68.

- Madden T. J., Ellen P. S., Ajzen I. (1992). A comparison of the theory of planned behavior and the theory of reasoned action. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18, 3–9.

- Mathes J., Schredl M., Göritz A. S. (2014). Frequency of typical dream themes in most recent dreams: An online study. Dreaming, 24, 57–66.

- McGrath J. E., Tschan F. (2004). Temporal matters in social psychology: Examining the role of time in the lives of groups and individuals. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Metcalf L. E., Bird A., Shankarmahesh M., Aycan Z., Larimo J., Valdelamar D. D. (2006). Cultural tendencies in negotiation: A comparison of Finland, India, Mexico, Turkey, and the United States. Journal of World Business, 41, 382–394.

- Rogelberg S. G., Scott C. W., Agypt B., Williams J., Kello J. E., McCausland T., Olien J. L. (2014). Lateness to meetings: Examination of an unexplored temporal phenomenon. European Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology, 23, 323–341. doi:

- Salmon E., Gelfand M., Ting H., Kraus S., Gal Y., Fulmer C. (2016). When time is not money: Why Americans may lose out at the negotiation table. Academy of Management Discoveries, 2, 349–367.

- Sanchez-Burks J., Lee F. (2007). Cultural psychology of workways. Handbook of Cultural Psychology, 1, 346–369.

- Tang L., Koveos P. E. (2008). A framework to update Hofstede’s cultural value indices: Economic dynamics and institutional stability. Journal of International Business Studies, 39, 1045–1063.

- Taras V., Steel P., Kirkman B. L. (2012). Improving national cultural indices using a longitudinal meta-analysis of Hofstede’s dimensions. Journal of World Business, 47, 329–341.

- Trompenaars F., Hampden-Turner C. (1997). Riding the waves of culture (2nd edition). London: Nicholas Brearley.

- Usunier J., Valette-Florence P. (2007). The time styles scale A review of developments and replications over 15 years. Time & Society, 16, 333–366.

- Van Eerde W., Buengeler C. (2015). Meetings all over the world: Structural and psychological characteristics of meetings in different countries. In The Cambridge handbook of meeting science (pp. 177–202). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Van den Scott L. J. K. (2014). Beyond the time crunch: New directions in the sociology of time and work. Sociology Compass, 8, 478–490.

- White L. T., Valk R., Dialmy A. (2011). What is the meaning of “On time”? The sociocultural nature of punctuality. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42, 482–493.

- Zwikael O., Shimizu K., Globerson S. (2005). Cultural differences in project management capabilities: A field study. International Journal of Project Management, 23, 454–462.