INTRODUCTION

Numerous scholars have studied clinical supervision over the last 40 years, solidifying the purpose and goals of supervision practices. As part of those efforts, some have identified supervision competencies (e.g., Neuer Colburn et al., ) and best practices across disciplines and among helping professionals, including counseling (Association for Counselor Education and Supervision [ACES], ; Borders et al., ), psychology (American Psychological Association [APA]), and social work (American Board of Examiners in Clinical Social Work, ). Borders () clarified that both competencies and best practices are key to quality clinical supervision practice and training, and although they should be considered complementary, competencies offer what a competent supervisor needs to know, and best practices describe what a supervisor does during supervision (p. 3). Neither competencies nor best practices, however, offer us the answers for how to conduct clinical supervision.

At the root of the efforts to determine competencies and best practices for clinical supervision, models emerged as the backbone of effective supervision practices. Scholars have criticized supervision models for being based primarily on the theoretical approaches and clinical opinion and experiences of their authors, thus lacking empirical support and conceptual comprehensiveness (e.g., Ellis & Dell, ; Holloway, ; Milne & Reiser, ). Yet, models are also deemed to be informative tools for training supervisors and could be researched more thoroughly to create the necessary evidence‐base (Bernard & Goodyear, ). Bernard and Goodyear also identified four main categories of supervision models: (1) psychotherapy‐based, (2) developmental, (3) process, and (4) second‐generation. The development and progress of supervision practice is discernable across the chronological presentations of these categories; each offers us a wide array of supervisory focus and practice, filling in the gaps previous models failed to address. For example, psychotherapy‐based models focused on the supervisees’ personal world and abilities, while being criticized for blurred boundaries between counseling and supervision and limiting supervisees’ practice to one theoretical focus of therapy (Bernard & Goodyear, ). Developmental models expanded the focus of supervision by emphasizing supervisees’ professional development needs in a pantheoretical manner, but they focused minimally on supervisees’ individual characteristics (e.g., learning styles) and the supervision process (Corey et al., ). As supervision is both educational and relational, scholars subsequently focused on the processes of supervision in the third category of models.

Due to the nuanced and idiosyncratic nature of clinical supervision, none of these models could be applied on their own to address all the necessities of supervision (Bernard & Goodyear, ). Thus, second‐generation models attempted to tackle limitations of previous models by blending models across categories, expanding on underemphasized areas (e.g., supervisees’ multicultural competence as well as social justice advocacy, attachment to supervisors), and observing common factors across all good supervision practices (e.g., Bernard & Goodyear, ). Supervisors are increasingly turning to empirically based approaches, integrating the common aspects of existing models, to inform their supervision practice. Watkins () reported 50 clinical supervision commonalities grouped in nine areas, building bridges across models, and detailing a trans‐theoretical understanding of supervision practice. Still, neither Watkins's report nor other common factors models were based on empirical data. Although seasoned supervisors may be able to integrate common factors and shift gears between various supervision models in practice, I have observed beginning supervisors often feeling overwhelmed by the number of supervision topics presented by the current supervision models. To advance supervision pedagogy and supervisor training, comprehensive, integrated, and systematized descriptions of supervision practices that are evidence‐based are warranted to develop empirically supported clinical supervision practices.

In this article, I present a cohesive and data‐driven approach to supervision practice based upon results from three empirical studies conducted on expert and seasoned supervisors’ supervision cognitions. The proposed model unifies existing supervision models’ key premises in a meaningful manner, while uniquely highlighting the underemphasized areas of supervision practice. Representing declarative, procedural, conditional, and conceptual knowledge (Ambrose et al., ) structures of expert supervisors, the Cohesive Model of Supervision (CMS) exemplifies the complementary nature of supervision competencies and best practices.

METHODS

Research‐base for the Cohesive Model of Supervision (CMS): concept mapping

The CMS is based on three empirical studies involved separate samples of expert supervisors’ supervision cognitions (Kemer, ; Kemer et al., , ). In all three studies, I utilized Concept Mapping (CM; Kane & Trochim, ), an exploratory sequential mixed‐methods design, to examine the knowledge structures of expert supervisors (Kemer, ; Kemer et al., , ). Being considered as a community‐engaged and action research design (Thompson & Burke, ), CM emerged from education, public health, and organizational psychology field research (Kane & Trochim, ). Particularly peaking counseling scholars’ attention in the last two decades (e.g., counseling alliance, Bedi, ; moral commitment, Pope & Cashwell, ), CM is an ideal design for theory development and program planning and evaluation research to form a common framework that represents ideas and/or experiences of diverse groups of stakeholders.

CM includes six steps: (1) preparation, (2) generation of statements, (3) structuring of statements, (4) representation of statements, (5) interpretation of maps, and (6) utilization of maps (Kane & Trochim, ). Per CM procedures, researchers involve stakeholders in the process of developing (Steps 1 and 2), structuring (Steps 3 and 4), and finalizing the data (Steps 5 and 6) to ensure testimonial (Bedi, ) as well as internal and external representational validity (Rosas & Kane, ), which are critical premises (trustworthiness/validity) of CM research, safeguarding stakeholders’ voice in the results than researchers’ perspectives and/or perceptions of the data. Being optional, Step 6 was beyond the scope of the three studies’ research questions, whereas current development study of CMS is a collective utilization of the three concept maps obtained from the studies (Kemer, ; Kemer et al., , ). I offer brief descriptions for the study procedures as well as collected data leading up to CMS below.

Steps 1 and 2: preparation and generation of statements

In all three studies, preparation (selection of the participants and development of study focus) was the core of research procedures. Expertise in ill‐defined fields, like clinical supervision, can be elusive (Tracey et al., ). Thus, the selection of expert supervisors (inclusionary criteria) was particularly critical for the targeted expertise and credibility of the results. Besides being diligent with defining and selecting experts from both academic and field settings, focus and prompt of the studies (e.g., One specific thing I think about in planning for, conducting, and evaluating my supervision sessions is…) aimed at obtaining a comprehensive picture of expert supervisors’ supervision considerations. In each of the three studies, Institutional Review Board approvals were obtained prior to data collection.

A total of 39 expert supervisors of academe and site supervision (26 counselor educators, 12 counseling psychologists) participated once across the three concept mapping studies (Kemer, ; Kemer et al., , ). With an average of 22.64 years of supervision practice, 29 academe experts from the two studies (Kemer, ; Kemer et al., ) conjointly published 32 books (not including different editions), 145 book chapters, and 464 peer‐reviewed articles; provided 739 professional presentations and 134 workshops; and received 156 awards and/or award nominations on supervision and/or counselor training. For expert site supervisors, I sought out nominations from faculty (e.g., university supervisors) and supervisees in Arizona (see Kemer et al., ). Ten expert site supervisors reported an average of 8.75 years of supervision practice, all held master's degrees in counseling, and four also had doctoral degrees in counseling psychology, holding a variety of professional credentials (e.g., licensed professional counselor and licensed psychologist) and practicing at community mental health and college counseling center settings. Across the 3 studies, expert supervisors generated a total of 571 supervision cognitions; 195, 167, and 209 statements, respectively (Kemer, ; Kemer et al., , ).

Steps 3 and 4: structuring and representation of statements

In each study, next, expert supervisors (individually) organized the statements into conceptually meaningful groups. Supervisors’ groupings of the statements were aggregated to obtain group similarity matrices (GSMs) as inputs to run two‐dimensional, nonmetric multidimensional scaling (MDS) analyses, yielding point maps unique to each study. In all three studies, stress values for the two‐dimensional MDS solution fit were within the range of obtained values in nearly 95% of CM studies (i.e., 0.205–0.365; Kane & Trochim, ), while staying below 0.396 to have robust outcomes (Sturrock & Rocha, ). Using the coordinate values for the statements from the MDS solutions, hierarchical cluster analyses resulted in dendrograms representing clusters of statements. In research teams, we utilized the point maps and the dendrograms to obtain statistically driven and conceptually meaningful preliminary clusters and maps for each of the datasets to be interpreted and finalized in the last step, focus group.

Step 5: interpretation of maps—focus groups

Samples of expert supervisors in each study attended a focus group to review, examine, and finalize the clusters and regions/areas (clusters of clusters on the concept map). More specifically, I asked the participants to “(a) engage in dialogue on the reasonableness of statements in each of the preliminary clusters, (b) discuss the appropriateness of the labeling of each cluster, and (c) view all clusters and their locations on the map to look for areas of conceptually meaningful groups of clusters” (Kemer, , p. 80). Across the 3 studies (Kemer, ; Kemer et al., , ), experts finalized different numbers of clusters (25, 15, and 27, respectively) and areas (5, 3, and 3, respectively) representing major areas of experts’ supervision cognitions and practices, revealing an almost identical underlying organization for expert supervisors’ cognitions in conducting clinical supervision. For detailed descriptions of the CM methodology, samples, and results, readers can refer to the original sources (Kemer, ; Kemer et al., , ).

Development of CMS via content analysis

To develop the CMS, I conducted a content analysis procedure utilizing the data and results obtained from the three studies. Content analysis is “a research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from texts (or other meaningful matter) to the contexts of their use” (Krippendorff, , p. 24). As the three CM studies offered me frameworks that were very similar, I followed a directed content analysis paradigm in the current study (Hsieh & Shannon, ). According to Hsieh and Shannon, in directed content analysis, the codes or coding frame could be derived from theory or relevant research findings while being defined before and during analysis. As the coding frame (areas and clusters) as well as the units of analysis (respective statements) in the three studies were already established by each study's participants, the goal of the current content analysis was to align three frameworks adhering to the original findings. Two researchers involved in the data analysis process, where I served as the coder and other researcher was the auditor. Being familiar with two of the datasets from the previous three studies, the auditor was a full professor of counseling and counselor education with an expertise in clinical supervision and a substantial record of clinical supervision scholarship.

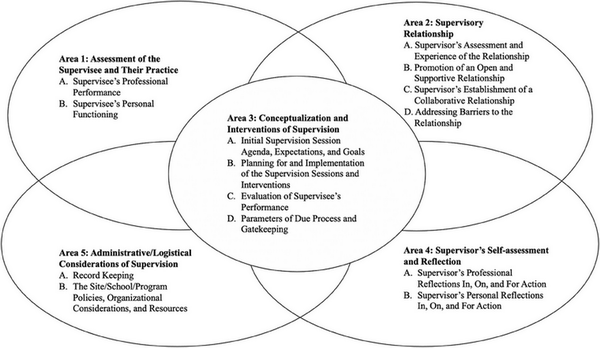

Examining the three frameworks, first, I reviewed the clusters (groupings of statements represent expert supervisors’ cognitions) and the main areas (groupings of similar clusters) across the three concept maps for commonalities. Although similar at the cluster‐level, three main areas were present in two of the maps (Kemer, ; Kemer et al., ), whereas the other map presented the clusters in five main areas (Kemer et al., ). Upon completing a detailed review, I observed the five‐area framework to be more comprehensive and thorough for the general CMS framework (coding frame). Next, I merged conceptually similar clusters across the three datasets and kept the unique ones as separate clusters. As part of this process, I merged some of the statements to conceptually appropriate clusters, following the results from the original studies. Then, I sent the original and merged datasets to the auditor to review each cluster along with the statements from all three datasets. They made a wide variety of comments and observational points, with suggestions to move statements from one cluster to another, merge clusters, and reword some of the cluster labels. Out of 549 statements, the auditor made 27 specific suggestions to move statements to different clusters, marking the interrater reliability (consensus) between the two of us at 95%. Based on the auditor's comments, I agreed to move 15 of the 27 suggested statements. Per auditor's comments, I also revised the labels of eight clusters and merged four clusters to create a new cluster that represented a similar theme. I named each cluster in the final solution to represent the respective statements, utilizing original cluster labels. Finally, the auditor reviewed the final cluster solution, which included 5 main areas with 14 clusters and 20 subclusters, forming the conceptual map of the CMS (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

Conceptual map for cohesive model of supervision (CMS).

RESULTS

Cohesive model of clinical supervision (CMS)

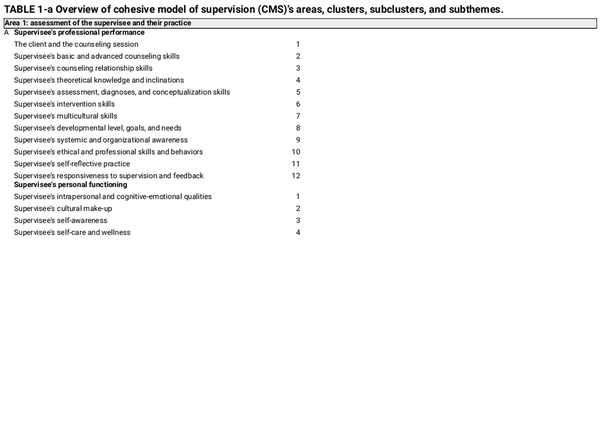

Expert supervisors’ clinical supervision cognitions were represented in five main areas of supervisory practice: (1) assessment of supervisees and their practice, (2) supervisory relationship, (3) conceptualization and interventions of supervision, (4) supervisors’ self‐assessment and reflection, and (5) administrative/logistical considerations of supervision. Each area included a variety of clusters, with subclusters in Areas 1 and 3 that also addressed different aspects of the specific supervision area. The areas and clusters of the CMS are distinct but interrelated, demonstrating that supervisors can focus on certain areas separately, yet continuously utilize all areas interactively for a thorough and comprehensive assessment of the supervisee, relationship progress, and supervisory process. See Table 1 for the overview of areas, clusters, subclusters, and subthemes of the CMS.

Area 1: assessment of supervisees and their practice

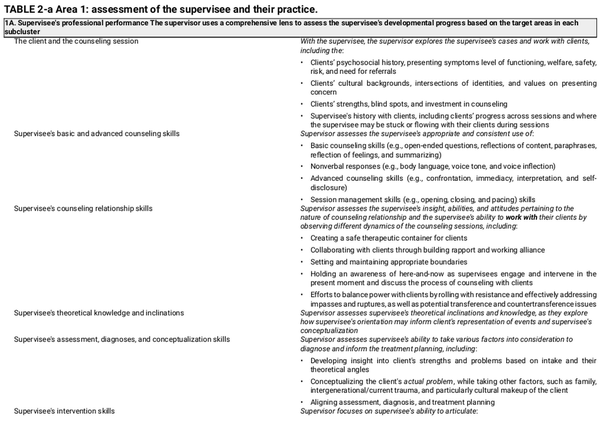

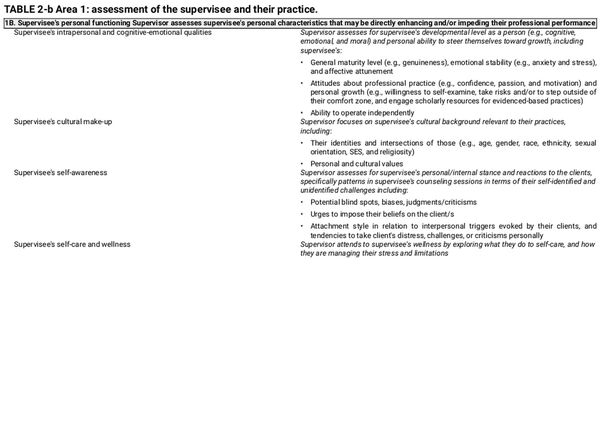

In the first area, supervisor assesses the supervisee through a comprehensive lens. Fundamental to all other areas of the model, this area establishes the basis of supervisor's work. Via their assessment of the supervisee, supervisor plans for, conducts, and reflects on supervision as they continue to reassess and reinform the supervisory process. This area targets two main presentations of the supervisee: 1A. supervisee's professional performance and 1B. supervisee's personal functioning. Supervisee's Professional performance cluster includes 12 subclusters that assess for a range of skills and dispositions that are integral to effective counseling practice with clients. Supervisee's Personal Functioning cluster involves important personal qualities of the supervisee that may not only affect their counseling practice but also the supervisory process. See Table 2 for detailed descriptions for each of the clusters and respective subclusters.

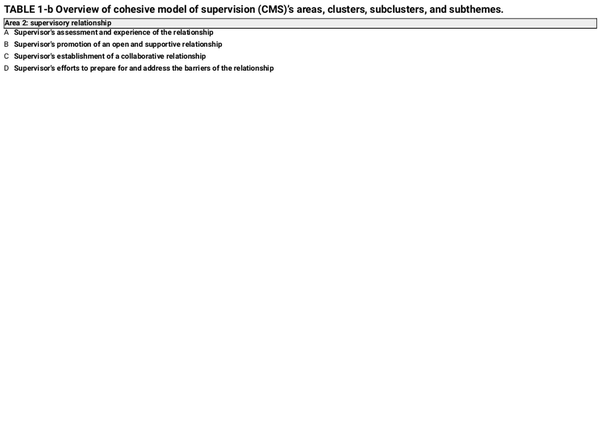

Area 2: supervisory relationship

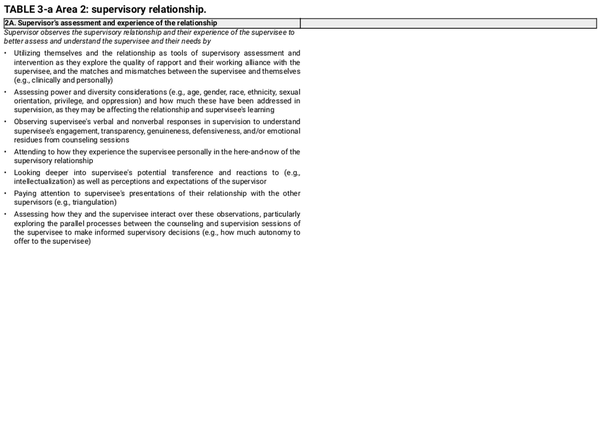

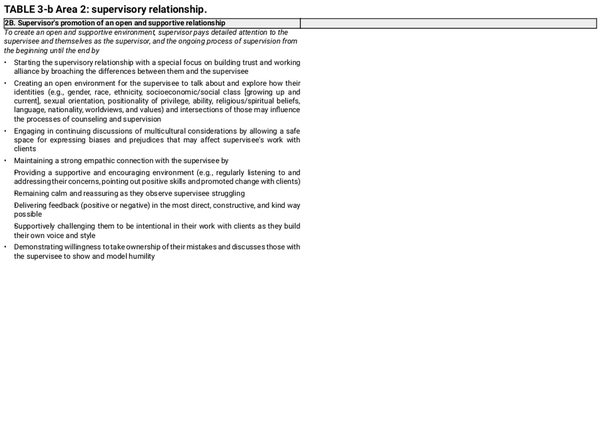

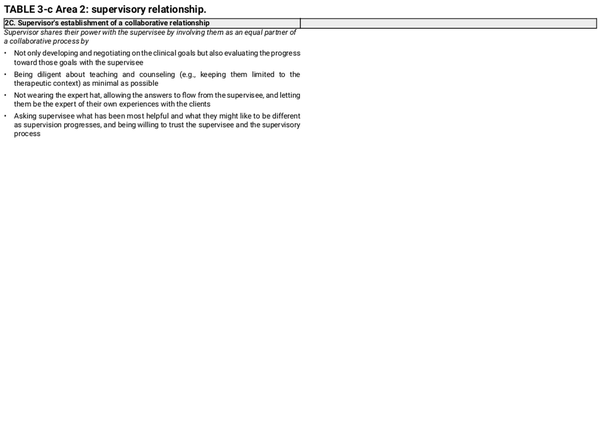

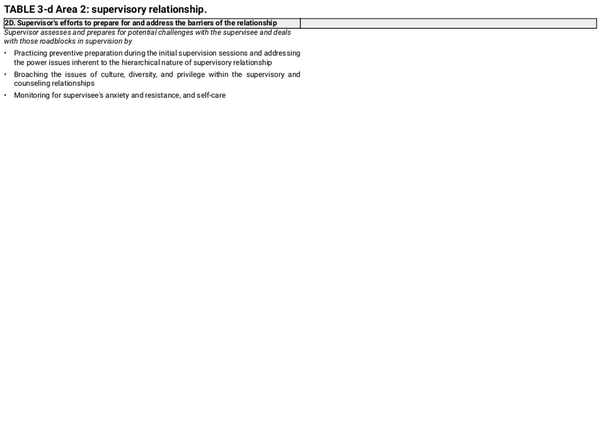

In the second area, supervisor observes the supervisory relationship as a bridge between assessment of the supervisee and their work, and conceptualization and interventions of supervision areas, as they continuously assess, intervene, and reassess the relationship. Supervisory relationship area involves four main relationship considerations of the supervisory process: 2A. supervisor's assessment and experience of the relationship, 2B. supervisor's promotion of an open and supportive relationship, 2C. supervisor's establishment of a collaborative relationship, and 2D. supervisor's efforts to prepare for and address the barriers of the relationship. See Table 3 for detailed descriptions for each of the clusters.

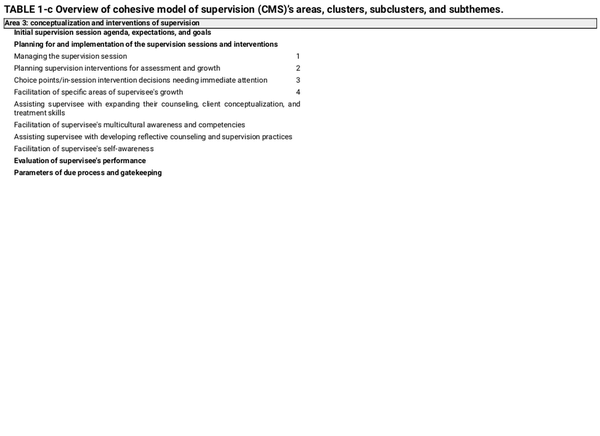

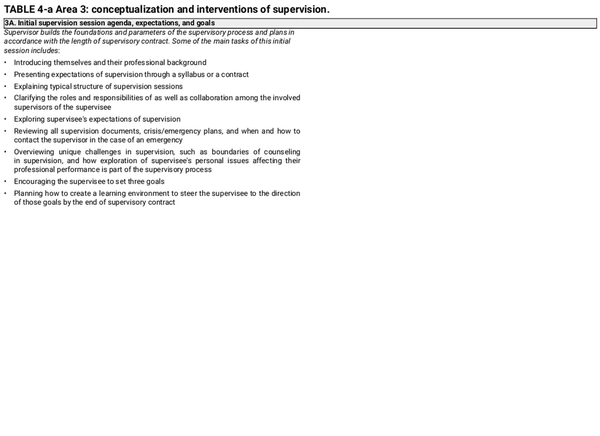

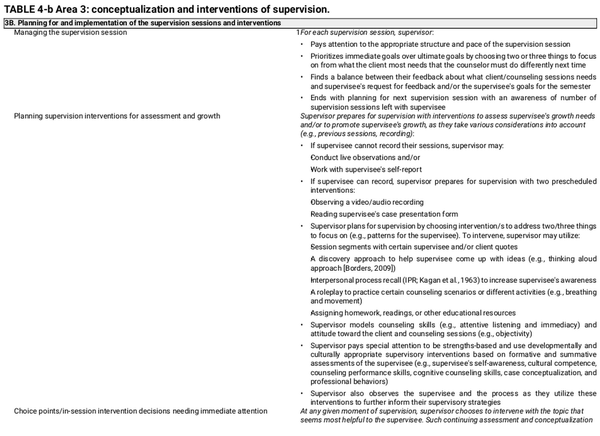

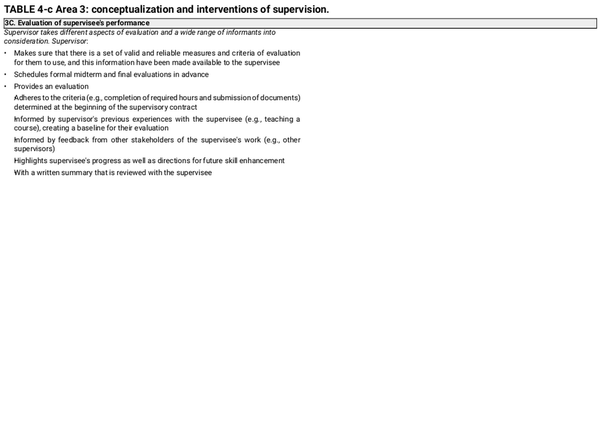

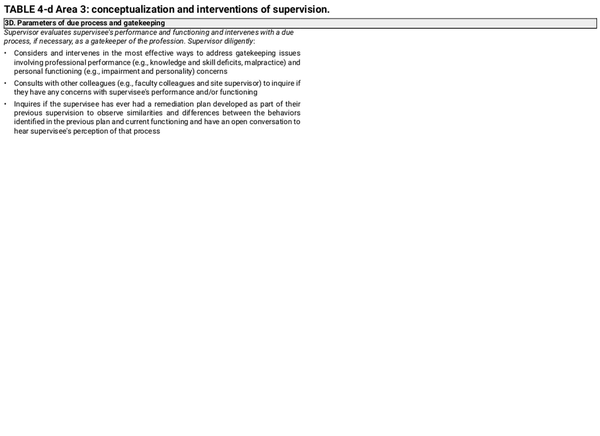

Area 3: conceptualization and interventions of supervision

In this area, supervisor starts, structures, and informs their supervisory conceptualization and interventions based on the assessment and observation points from the first two areas. This area presents to supervisors with not only what to do but also how to do those in supervision. The area outlines and details four main clusters: 3A. initial supervision session agenda, expectations, and goals, 3B. planning for and implementation of the supervision sessions and interventions, 3E. evaluation of supervisee's performance, and 3D. parameters of due process and gatekeeping. Planning for and implementation of the supervision sessions and interventions cluster also outlines four subclusters one of which with four specific subthemes. See Table 4 for detailed descriptions for each of the clusters and respective subclusters as well as subthemes.

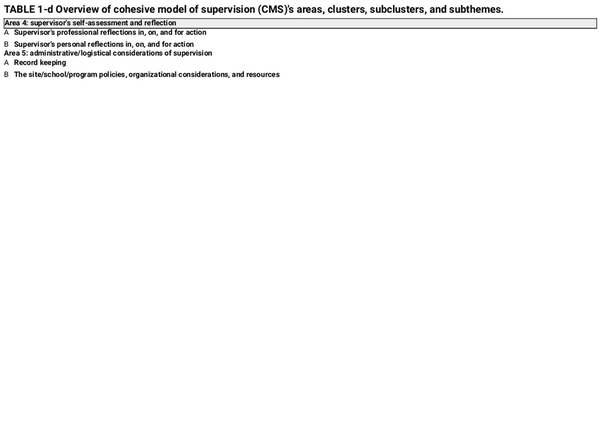

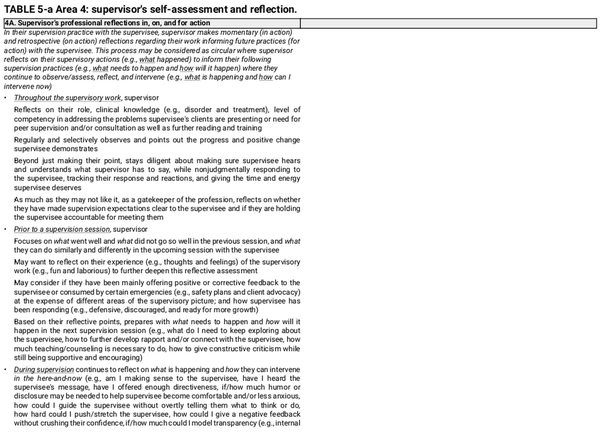

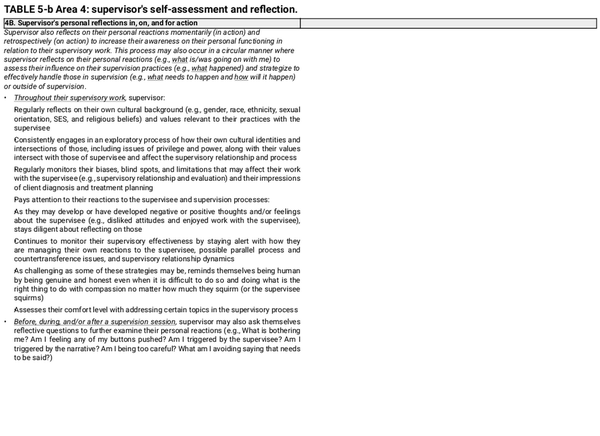

Area 4: supervisor's self‐assessment and reflection

Supervisor also assesses and reflects on their own professional performance and personal functioning in a detailed manner to inform their practices. This area represents two main clusters: 4A. supervisor's professional reflections in, on, and for action and 4B. supervisor's personal reflections in, on, and for action. See Table 5 for a detailed outline for each of the clusters.

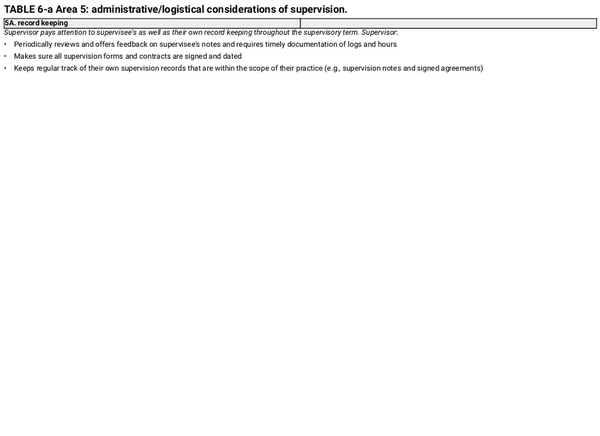

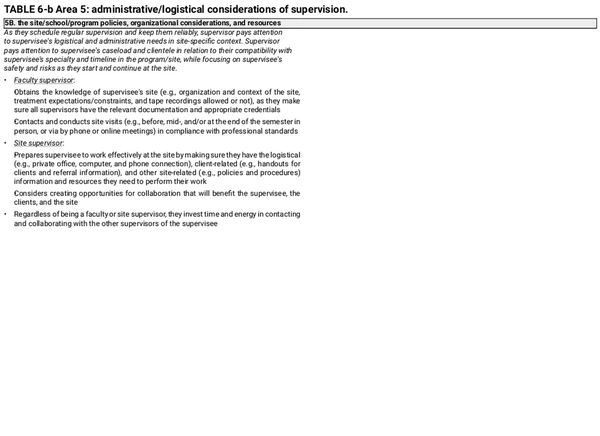

Area 5: administrative/logistical considerations of supervision

Supervisor pays attention to administrative aspects of the supervisory work with variations based on the supervisory setting. This last area has two main clusters: 5A. record keeping and 5B. the site/school/program policies, organizational considerations, and resources. See Table 6 for the presentation for each of the clusters.

DISCUSSION

CMS is the first empirically based pantheoretical supervision model voicing expert supervisors’ cognitions when providing and reflecting on their supervision practices. CMS offers a logical sequence of supervisor's assessment, conceptualization, planning, and intervention, yet is not a stage model. Each of the area considerations continuously recur throughout the supervisory contract as the supervisor tailors their supervision to address supervisee's needs and setting necessities. Including all nine common areas observed across the supervision models (Watkins, ), CMS unifies existing supervision models and literature in a systematized way. CMS particularly overlaps with the ACES Best Practices (Borders et al., ) and APA Guidelines for Clinical Supervision (APA, ). Such overlaps were not surprising as both ACES Best Practices and APA Guidelines for Clinical Supervision were created through comprehensive reviews of supervision research and literature. However, further operationalizing the best practices and competency guidelines, CMS also conceptualizes them in a concise and simpler structure. In this simplified organization of complex supervision work, the model translates the existing knowledge of supervision into a process‐ and action‐oriented presentation, almost resembling the counseling process. Specifically, CMS provides us with a supervisory process, based on continuous assessment where the supervisor not only focuses on the supervisee and the supervisory relationship, but also scrutinize their own professional performance and personal responses as they inform their clinical and administrative supervision work. Although CMS sheds light on what (declarative knowledge), how (procedural knowledge), and the elaboration on what and how continuum (conditional and conceptual knowledge; Ambrose et al., ) across all five areas, when compared to the existing supervision literature, the supervisor's self‐assessment and reflection area (see Table 5, Area 4) clearly and judiciously emphasizes the critical role of supervisor, their awareness, and intentionality in the supervisory process.

The first area, Assessment of Supervisees and Their Practice, details the supervisee‐focus in a comprehensive manner. Not being a novel idea, split focus on supervisee's professional performance and personal functioning is a concise presentation of the two main areas of assessing the supervisee. Particularly, in the view of increasing focus on trauma‐informed supervision (e.g., Berger & Quiros, ; Knight, ), supervisor's approach to supervisee's personal history as well as self‐care and wellness in relation to their counseling practices are targeted in this area. Supervisee‐focused points from ACES Best Practices (e.g., goal setting, diversity, and ethical considerations; Borders et al., ), APA Guidelines for Clinical Supervision (e.g., assessment/evaluation/feedback, professional competence problems; APA, ) and existing models (e.g., focus areas, discrimination model [DM; Bernard, ]; domains and structures, integrated developmental model [IDM; Stoltenberg & McNeill, ]; personhood of the supervisee, supervisee‐centered psychodynamic supervision [Ekstein & Wallerstein, ]; social justice supervision [Dollarhide et al., ]; supervisee characteristics and change processes, common factors [Watkins, ]) are all represented in this area of CMS.

As a key ingredient of the process (e.g., Watkins, ), Area 2, Supervisory Relationship is very much in line with the literature while offering some nuanced information. What appears to be unique about CMS's supervisory relationship area is the clear emphasis on relationship being both an assessment and intervention tool of the supervisory process, where supervisor continuously assesses the relationship, intervenes accordingly, and reassesses to intervene again. Although experts of academe did not report this nuance, expert site supervisors described supervisory relationship as an intervention in their supervision process and practices (Kemer et al., ). Although all four clusters do, the supervisor's assessment and experience of the relationship and supervisor's efforts to prepare for and address the barriers of the relationship clusters particularly emphasize supervisor's need to trust, integrate, and model their counseling skills to create a rich and therapeutic climate within the supervisory relationship and process, attending not only to supervisee's professional performance but also personal functioning. This area of CMS is particularly in line with the supervisory relationship from ACES Best Practices (Borders et al., ), APA Guidelines for Clinical Supervision (APA, ), and the existing models (e.g., systems approach to supervision [SAS; Holloway, ]; mode five, seven‐eyed model of supervision [SMS; Hawkins & Shohet, ]; psychodynamic [Frawley‐O'Dea & Sarnat, ]; humanistic‐existential [Farber, ]; social justice supervision [Dollarhide et al., ]; common factors [e.g., Watkins, ]).

As if the pistil of a flower, Area 3, Conceptualization and Interventions of Supervision was the core of the CMS, through which all other areas come to life (see Figure 1). This area of CMS particularly addresses what (declarative knowledge) to focus on with the supervisee and supervisory process, and how (procedural knowledge) to do that. Under the Planning for and implementation of the supervision sessions and interventions cluster, subclusters of managing the supervision session, planning supervision interventions for assessment and growth, choice points/in‐session intervention decisions needing immediate attention, and facilitation of specific areas of supervisee's growth and its subclusters (i.e., assisting supervisee with expanding their counseling, client conceptualization, and treatment skills, facilitation of supervisee's multicultural awareness and competencies, assisting supervisee with developing reflective counseling and supervision practices, facilitation of supervisee's self‐awareness) depict a systematized picture for what‐to‐how continuum (conditional and conceptual knowledge; Ambrose et al., ) in the supervisory process. Clearly offering directions to develop and deepen supervisee reflexivity (e.g., Guiffrida, ; Neufeldt et al., ; Watkins, ) on professional and personal matters, this area parallels different aspects of the supervisory contract (i.e., initiating supervision, goal setting, conducting supervision sessions, providing feedback, and conducting evaluations) and other Best Practices’ areas (e.g., diversity and advocacy considerations, documentation, and ethical considerations; Borders et al., ) and APA Guidelines for Clinical Supervision (i.e., diversity and professionalism; APA, ). Similarly, supervisor roles (i.e., teacher, counselor, consultant) from DM (Bernard, ) and supervision interventions from IDM (i.e., facilitative, prescriptive, conceptual, catalytic; Stoltenberg & McNeill, ) as well as certain common factors areas (e.g., supervisor tasks and roles, supervisor common practices; Watkins, ) are also represented in this area of CMS.

In Area 4, Supervisor's Self‐Assessment and Reflection, Schön's () premises on reflection‐in‐action and reflection‐on‐action, as well as reflection‐for‐action (Borders et al., ), were clearly stated by the experts. Emphasizing the critical role of supervisor's self‐reflective practice in a detailed manner, this area offers depth and nuance to supervisor's practices when compared to the existing supervision models and is the main unique contribution of the CMS to the current supervision literature. This area provides a detailed guideline for self‐assessment and reflection to each individual supervisor's unique practices as well as each supervisory dyad's idiosyncratic processes, while addressing how a supervisor's reflective practice may look at its finest. In this area, it is fair to say that expert supervisors’ counselor identities merged with their clinical supervisor identities at an advanced level. Moreover, expert supervisors’ intentional efforts on assessing supervisee's as well as their own reflexivity as they intentionally planned and intervened in supervision was one of the highlighted areas of CMS, affirming supervision as a reflective process all around. This area also supported the supervisor from the ACES Best Practices, APA Guidelines for Clinical Supervision (APA, ), SAS (Holloway, ), and SMS (mode six; Hawkins & Shohet, ) as well as Dollarhide et al.’s () emphasis on supervisor self‐evaluation for social justice supervision.

Finally, Administrative/Logistical Considerations of Supervision, Area 5, of CMS offered unique considerations for university and site supervisors. Supervision models and literature frequently speak to clinical supervisors without offering much direction regarding the factors driven by their settings. Therefore, the parallel but also nuanced information regarding site and university supervisors’ administrative considerations were also a unique presentation of the CMS. This area was in line with the documentation and some aspects of the supervisor areas from ACES Best Practices (Borders et al., ), and ethical, legal, and regulatory considerations domain from APA Guidelines for Clinical Supervision (APA, ).

Practice implications of CMS

Supervisors, counselor educators, as well as counselor and supervisor training programs may benefit from utilizing CMS and its premises. CMS was built on the results obtained from seasoned supervisors of counselor trainees from master's and doctoral programs in counselor education and counseling psychology. Yet, obtaining a parallel structure to CMS from supervisors of residents in counseling (Kemer et al., ), we also observed residency supervisors’ supervision thoughts addressing all five areas and respective 14 clusters and 20 subclusters, with an additional cluster (Kemer et al., ). Thus, CMS emerges to offer an overarching framework for supervisors of counselor trainees and counselors pursuing licensure to (1) assess specific aspects of supervisee's professional performance and personal functioning, (2) utilize supervisory relationship as a bridge between their assessment and supervisory conceptualizations and interventions, (3) intentionally start, conduct, and intervene in the supervisory process based on their comprehensive assessment, (4) assess and reflect on their practices and personal reactions, and (5) attend to the administrative aspects of their work.

Using CMS, supervisors may begin with a specific area and its clusters to continue with the other areas and respective clusters in a circular manner in their supervisory practices. For example, supervisors may consider starting with assessment of the supervisee's professional and personal qualities (Area 1), yet supervisory relationship (Area 2) factors may be available to the supervisor earlier for assessment in the supervisory process. Thus, as they attend to the initial supervision session agenda, expectations, and goals (Area 3, Cluster 3A), supervisors may also focus on their experience of the relationship and the supervisee from the very first interaction (e.g., email, first session; Cluster 2A). As the supervisory relationship progresses, supervisors may specifically focus their attention to differing needs of the supervisee not only related to professional performance (Cluster 1A) but also personal functioning (Cluster 1B). Based on their assessment of supervisee's needs (e.g., Clusters 1A2. basic and advanced counseling skills, 1A6. intervention skills, 1B3. self‐awareness) or supervisory process necessities (e.g., Clusters 2B. promotion of an open and supportive relationship, 2D. Efforts to prepare for and address the barriers of the relationship), supervisor intentionally conceptualizes and prepares for the practice of supervision (e.g., Cluster 3B4. facilitation of specific areas of supervisee's growth, such as expanding their counseling, client conceptualization, and treatment skills, multicultural awareness and competencies). Intending to utilize supervisory strategies relevant to their conceptualization (e.g., roleplays, interpersonal process recall), supervisor must also be ready to intervene when the supervisory process requires more urgent assessment and interventions (e.g., Cluster 3B3. choice points/in‐session intervention decisions needing immediate attention), such as ethical/legal concerns or crisis with the client and/or the supervisee. In a parallel process, supervisor must regularly reflect on their own contributions to the supervisory process prior to, during, and/or after supervision (i.e., Area 4: professional and personal reflections in, on, & for action) for further intentional preparation for supervision (e.g., use a different supervisory strategy to help supervisee in a specific area, receive consultation/supervision to compartmentalize personal reactions to the supervisee). Based on their supervisory process and context, though, each supervisor may configure different areas and clusters of the CMS based on their supervisee's needs (e.g., developmental level), their own supervisory style, and practice setting considerations, whereas all areas and respective clusters would continuously come into the supervisory picture as the supervisory term progresses.

Counselor educators may also consider using CMS as they supervise doctoral internship. Besides offering CMS as a framework in their didactic supervision courses, during supervision‐of‐supervision, CMS's outline from Table 1 may be utilized as a supervision form for the supervisor trainees to highlight the emphasis of their work and training as they present supervisory cases. What supervisor trainees focus on and where they may be struggling and thriving may offer the necessary training opportunities for the supervisors of supervisors to deepen that area of trainees’ practices. Similarly, CMS's five‐area framework may also be applicable to other internship areas of CACREP‐accredited doctoral level training (e.g., teaching, research, and leadership). For example, as they pay attention to the supervisory relationship (e.g., research mentorship), supervisors of researchers in training (RiTs) may consider assessing RiTs and their research practices, conceptualize, and intervene intentionally to promote research competencies and researcher identity development, reflect on their own biases and practices (e.g., qualitatively/quantitatively oriented) as a research supervisor, and consider administrative aspects of the work (e.g., institution‐specific IRB procedures). Counselor educators, particularly, supervisors of supervisors may also consider CMS for their own practices with supervisor trainees as a general outline for supervision of supervision practice as well as training.

Finally, CMS may be useful for counselor trainees as well as fully and partially licensed counselors to assess their own practice and clarify supervision needs for continuing professional growth and consider their goals for becoming a supervisor. Particularly, assessment of the supervisee and their practice area outlines a professional and personal considerations checklist for counselors from any developmental level to set up intentional goals for supervision. Merging these considerations with the reflective practices from supervisory relationship and supervisor's self‐assessment and reflection areas, counselors may embrace their own progress and process, while creating a conscious parallel process for their clients in counseling sessions.

Limitations and further research needs of CMS

First and foremost, the samples from all three studies mainly represented white cisgender female participants. Therefore, despite continuous presentations of multicultural and social justice focus, the datasets CMSs were collected prior to 2020 and may be limited in directions for socially just, anti‐racist, and anti‐oppressive supervision practices; thus, supervisors utilizing CMS would still benefit from further reflecting on and including social justice advocacy and action (Dollarhide et al., ) in their practices. Similarly, further research is needed to deepen CMS's focus on social just, anti‐racist, and anti‐oppressive counseling and supervision practices. Second, in all three studies, I asked supervisors to primarily focus on their individual supervision sessions with their supervisees. Thus, research on what aspects of the CMS is transferrable to and what else is critical to consider in triadic and group supervision modalities are warranted. I did not ask the participants to focus on a specific supervisee developmental level (e.g., master's level practicum, doctoral internship, and licensure), and participants from all three studies reported working with a range of supervisees offering a comprehensive picture. However, further research is needed to understand whether supervisors would focus on specific clusters and subclusters of the model with different supervisee profiles. For example, researchers may examine if supervisors prioritize any of the clusters and subclusters from the assessment of the supervisee and their work or supervisor's self‐assessment and reflection areas as they work with supervisees from different developmental levels (e.g., master's level practicum, licensure). As the focus of all three studies was on counseling supervision, participants included supervisors from counselor education and counseling psychology fields. As the CMS is a data‐driven model with a general framework that may be applicable to other areas of CACREP‐accredited doctoral level training (e.g., teaching, research, and leadership) as well as to other disciplines, future replication studies with supervisors of other training areas and disciplines may further our understanding on the common and distinct aspects of supervisory practices across training areas and fields. Particularly, future research may involve supervisors of supervisor trainees to test versatility of the model as the general outline of the CMS may particularly be applicable to supervisor training. Finally, CMS offers an outline that may allow researchers to utilize nested models for supervision and counseling outcome research via quasi‐experimental and/or analogue designs to test connections between supervisory and counseling processes and the contribution of CMS‐outlined supervision on counseling and client outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author gratefully acknowledges the feedback and support from Dr. DiAnne L. Borders, Dr. Amber Pope, Dr. Mine Aladag, Dr. Jeffry Moe, Dr. Melissa Luke, Dr. Anita Neuer Colburn, Dr. E. d. Neukrug, and Dr. Vanessa Dominguez.

REFERENCES

- Ambrose S. A., Bridges M. W., DiPietro M., Lovett M. C., & Norman M. K. (2010). How learning works: 7 Research‐based principles for smart teaching. Jossey‐Bass.

- American Board of Examiners in Clinical Social Work . (2004). Clinical supervision: A practice specialty of clinical social work. American Board of Examiners in Clinical Social Work. https://www.abcsw.org/assets/ClinSupervisionIntro.pdf

- American Psychological Association . (2014). Guidelines for clinical supervision in health service psychology. American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/about/policy/guidelines‐supervision.pdf

- Association for Counselor Education and Supervision (ACES) . (2011). Best practices in clinical supervision. ACES. https://acesonline.net/wp‐content/uploads/2018/11/ACES‐Best‐Practices‐in‐Clinical‐Supervision‐2011.pdf

- Bedi R. P. (2006). Concept mapping the client's perspective on counseling alliance formation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022‐0167.53.1.26

- Berger R., & Quiros L. (2014). Supervision for trauma‐informed practice. Traumatology, 20(4), 296–301. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0099835

- Bernard J. M. (1979). Supervisor training: A discrimination model. Counselor Education and Supervision, 19, 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556‐6978.1979.tb00906.x

- Bernard J. M., & Goodyear R. K. (2019). Fundamentals of clinical supervision (6th ed.). Pearson.

- Borders L. D. (2009). Subtle messages in clinical supervision. The Clinical Supervisor, 28(2), 200–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325220903324694

- Borders L. D. (2014). Best practices in clinical supervision: Another step in delineating effective supervision practice. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 68(2), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2014.68.2.151

- Borders L. D., Glosoff H. L., Welfare L. E., Hays D. G., DeKruyf L., Fernando D. M., & Page B. (2014). Best practices in clinical supervision: Evolution of a counseling specialty. The Clinical Supervisor, 33(1), 26–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2014.905225

- Borders L. D., Welfare L. E., Sackett C. R., & Cashwell C. (2017). New supervisors' struggles and successes with corrective feedback. Counselor Education and Supervision, 56(3), 208–224. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12073

- Corey G., Haynes R., Moulton P., & Muratori M. (2010). Clinical supervision in the helping professions (2nd ed.). American Counseling Association.

- Dollarhide C. T., Hale S. C., & Stone‐Sabali S. (2021). A new model for social justice supervision. Journal of Counseling and Development, 99, 104–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12358

- Ekstein R., & Wallerstein R. S. (1972). The teaching and learning of psychotherapy (2nd ed.). International Universities Press.

- Ellis M. V., & Dell D. M. (1986). Dimensionality of supervisor roles: Supervisors' perceptions of supervision. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 33(3), 282. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022‐0167.33.3.282

- Farber E. W. (2010). Humanistic–existential psychotherapy competencies and the supervisory process. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 47(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018847

- Fitch J. C., Pistole M. C., & Gunn J. E. (2010). The bonds of development: An attachment‐caregiving model of supervision. The Clinical Supervisor, 29(1), 20–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325221003730319

- Frawley‐O'Dea M. G., & Sarnat J. E. (2001). The supervisory relationship: A contemporary psychodynamic approach. Guilford Press.

- Goodyear R. K., Tracey T. J., Claiborn C. D., Lichtenberg J. W., & Wampold B. E. (2005). Ideographic concept mapping in counseling psychology research: Conceptual overview, methodology, and an illustration. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 236. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022‐0167.52.2.236

- Guiffrida D. A. (2005). The emergence model: An alternative pedagogy for facilitating self‐reflection and theoretical fit in counseling students. Counselor Education and Supervision, 44(3), 201–213. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556‐6978.2005.tb01747.x

- Hawkins P., & Shohet R. (2012). Supervision in the helping professions. McGraw Hill Open University Press.

- Holloway E. L. (1987). Developmental models of supervision: Is it development? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 18(3), 209. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735‐7028.18.3.209

- Holloway E. L. (2016). Supervision essentials for a systems approach to supervision. American Psychological Association.

- Hsieh H. F., & Shannon S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Kagan N., Krathwohl D. R., & Miller R. (1963). Stimulating recall in therapy using video tape: A case study. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 10, 237–243. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0045497

- Kane M., & Trochim W. M. (2007). Concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Sage.

- Kemer G. (2020). A comparison of beginning and expert supervisors’ supervision cognitions. Counselor Education and Supervision, 59(1), 74–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12167

- Kemer G., Borders L. D., & Willse J. (2014). Cognitions of expert supervisors in academe: A concept mapping approach. Counselor Education and Supervision, 53(1), 2–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556‐6978.2014.00045.x

- Kemer G., Pope A. L., & Neuer Colburn A. A. (2017). Expert site supervisors’ cognitions when working with counselor trainees. The Clinical Supervisor, 36, 241–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2017.1305937

- Kemer G., Wambui Preston J., Schmoyer N., Akpakir Z., & Crofford H. (2024a). Supervision of residents in counseling: What do seasoned supervisors think? [Manuscript in preparation]. Department of Counseling and Human Services, Old Dominion University.

- Kemer G., Wambui Preston J., Schmoyer N., Akpakir Z., & Crofford H. (2024b). A content analysis of residency supervisors' supervision considerations. [Manuscript in preparation]. Department of Counseling and Human Services, Old Dominion University.

- Knight C. (2018). Trauma‐informed supervision: Historical antecedents, current practice, and future directions. The Clinical Supervisor, 37(1), 7–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2017.1413607

- Krippendorff K. (2012). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage.

- Milne D., & Reiser R. P. (2012). A rationale for evidence‐based clinical supervision. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 42(3), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879‐011‐9199‐8

- Morgan M. M., & Sprenkle D. H. (2007). Toward a common‐factors approach to supervision. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 33(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752‐0606.2007.00001.x

- Neuer Colburn A. A., Grothaus T., Hays D. G., & Milliken T. (2016). A Delphi study and initial validation of counselor supervision competencies. Counselor Education and Supervision, 55(1), 2–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12029

- Neufeldt S. A., Karno M. P., & Nelson M. L. (1996). A qualitative study of experts' conceptualizations of supervisee reflectivity. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 43, 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022‐0167.43.1.3

- Pope A. L., & Cashwell C. S. (2013). Moral commitment in intimate committed relationships: A conceptualization from cohabiting same‐sex and opposite‐sex partners. The Family Journal, 21, 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480712456671

- Rosas S. R., & Kane M. (2012). Quality and rigor of the concept mapping methodology: A pooled study analysis. Evaluation and Program Planning, 35(2), 236–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.10.003

- Schön D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. Jossey‐Bass.

- Stoltenberg C. D., & McNeill B. W. (2010). IDM supervision: An integrative developmental model for supervising counselors and therapists (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Sturrock K., & Rocha J. (2000). A multidimensional scaling stress evaluation table. Field Methods, 12, 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X0001200104

- Thompson J. R., & Burke J. G. (2020). Increasing community participation in public health research: Applications for concept mapping methodology. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 14(2), 243–250. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2020.0025

- Tracey T. J., Wampold B. E., Lichtenberg J. W., & Goodyear R. K. (2014). Expertise in psychotherapy: An elusive goal? American Psychologist, 69(3), 218–229. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035099

- Watkins C. E. Jr. (2015). Toward a research‐ informed, evidence‐based psychoanalytic supervision. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 29, 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02668734.2014.980305

- Watkins C. E. Jr. (2017). Convergence in psychotherapy supervision: A common factors, common processes, common practices perspective. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 27(2), 140–152. https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000040