Introduction

Lack of research attention for the alcohol hangover has resulted in the current absence of understanding of the pathology of the alcohol hangover and the lack of an effective treatment. Reviews note that the effectiveness of the majority of hangover treatments that are marketed has not been scientifically investigated. Those treatments that have been examined show no or little effectiveness, and the quality of most of these clinical trials have been criticized (; ). Although some products have been shown to bring relieve to certain hangover symptoms (e.g. reduce headache), other symptoms are not alleviated. Hence, still today the only effective way to prevent a hangover is to consume alcohol in moderation.

As the costs of hangovers are largely underestimated, policy makers and health care campaigns have not drawn much attention to the alcohol hangover. The few studies that did try to calculate the socio-economic costs of hangovers revealed that billions of dollars globally are lost annually due to absenteeism, reduced productivity, and increased risk of injury (; ; ; , ). Recent studies also showed that although during the hangover state driving is significantly impaired (), yet most drivers persist in driving while hungover (). Given its costs and negative consequences, the need for an effective hangover treatment is evident ().

It is a persistent popular believe that the absence of an effective hangover cure helps prevent drinkers from consuming even more alcohol than they do already. According to this viewpoint, drinking in moderation is currently the only effective way to prevent hangover, and this helps many drinkers limit excessive alcohol use. Unfortunately, this popular belief has also been adopted by many physicians and researchers. In this context, researchers have suggested that having no hangovers can be a gateway to alcohol dependence or abuse ().

It could then be hypothesized that if drinkers experience less hangover symptoms they might drink more alcohol. However, this is not supported by a recent study that found hangover severity not to be significantly correlated to the amount of alcohol consumed or the achieved estimated peak blood alcohol concentration (BAC) (). Moreover, examined the consequences of having a hangover for drinking on future occasions. They showed that more severe hangovers did not predict the likelihood of not drinking later that day. However, they did find that the quantity of alcohol consumed on that occasion was lower than usual consumption levels. Other researchers reported that having hangovers does not prevent drinkers from consuming the same amounts of alcohol on future drinking occasions ().

Taken together, the severity of intoxication or hangover effects seems unrelated to the actual amount of alcohol consumed. Up to now, however, no research has directly investigated if drinkers would consume more alcohol if there was an effective and affordable hangover treatment.

Given the lack of scientific data on the implications of developing an effective hangover treatment, the current study investigated whether drinkers who experience hangovers would (a) be willing to buy an effective hangover treatment and (b) whether using such a product would affect the amount of alcohol they consume.

Methods

In December 2016, an online survey was held among Dutch students, 18–30 years old. The survey was designed using www.surveymonkey.com and advertised via www.facebook.com. Online informed consent was obtained from all participants; no formal ethics approval was required to conduct this research, according to the Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects (CCMO). As a reward for participating, subjects could win a 100 Euro gift voucher. Data collection was conducted by NeuroClinics, and funded by Sen-Jam Pharmaceutical. Unrestricted use of the data was granted to the authors.

Demographic data on age, gender, and weight were collected. Weekly alcohol consumption was recorded, and the number of alcoholic drinks they consumed the day before their latest past-month hangover. Using a modified Widmark formula, taking into account gender and drinking time, the estimated peak BAC was calculated (). Overall hangover severity (i.e. a single one-item rating) and the severity of 22 individual symptoms were rated on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (absent) to 10 (extreme) ().

Subjects were asked whether they would buy an effective hangover treatment if it was available. The answering possibilities where “yes”, “no”, and “don’t know”, and a text box was provided to leave comments. Subjects were divided into three groups (“yes”, “no”, and “don’t know”) according to their answer on the question whether they would buy an effective hangover product, and alcohol consumption-related variables were compared using nonparametric statistics.

Next, subjects were asked whether they would consume more alcohol if an effective hangover treatment was available. Again, the answering possibilities where “yes”, “no”, and “don’t know”, and a text box was provided to leave comments. Subjects were divided into three groups (“yes”, “no”, and “don’t know”) according to their answer on the question whether they would consume more alcohol. Alcohol consumption-related variables of these three groups were compared using nonparametric statistics.

In a follow-up survey, conducted one week after the first survey, those subjects who left their email address were contacted again and specifically asked via an open-ended question to explain why they answered “yes”, “no”, or “don’t know” to the two questions posed in the first survey, i.e. (1) whether they would buy an effective hangover treatment if it was available and (2) whether they would consume more alcohol if an effective hangover treatment was available.

Statistical analysis

Only those subjects aged 18 to 30 years old who reported having a past-month hangover were included in the analyses. Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS, version 24.

For demographic variables and hangover severity scores, mean and standard deviation were computed. Using Independent Samples Mann–Whitney U tests, these variables we compared between those who would buy an effective hangover cure, those who do not know, and those who would not buy an effective hangover cure. Using the same test, these variables were also compared between those who state they would consume more alcohol when an effective hangover treatment was available, those who do not know, and those who state that they would not consume more alcohol.

Results

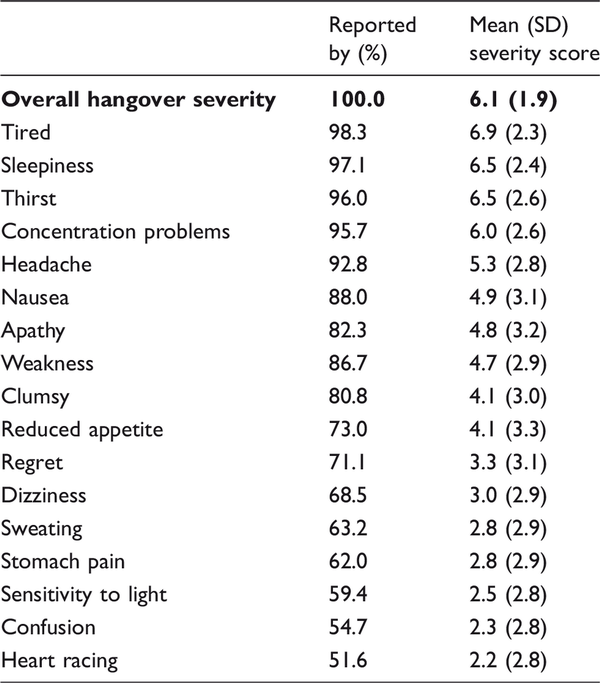

A total of 1837 subjects (50.4% men) who reported having had an alcohol hangover recently completed the survey. Their mean (SD) age was 20.8 (2.3) years old, and they reported consuming 13.6 (10.1) alcoholic beverages per week. Over a mean (SD) time period of 5.8 (2.0) hours of alcohol consumption, they reported consuming 12.6 (5.5) alcoholic drinks on the day before their latest alcohol hangover, which resulted in an estimated peak BAC of 0.19 (0.1)%. Mean (SD) overall hangover severity was 6.1 (1.9). The presence and severity of individual hangover symptoms is summarized in Table 1.

Would you buy it?

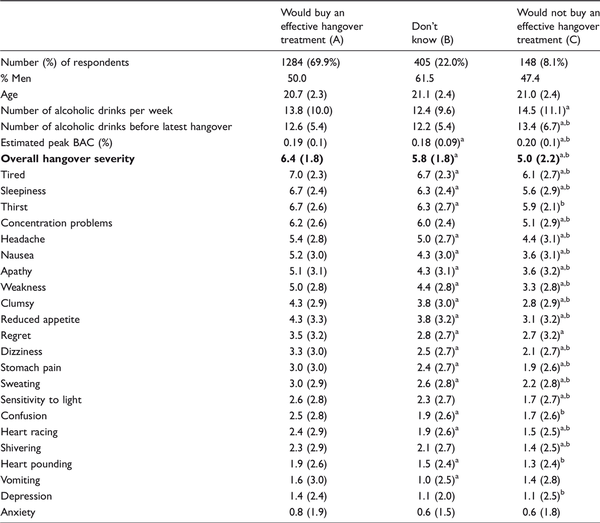

When asked whether drinkers would buy an effective hangover treatment was available, 69.9% answered yes. A minority of 8.1% answered “no” and 22.0% did not know. Demographics and hangover characteristics of the three groups are summarized in Table 2.

The analyses revealed that buyers do not significantly differ from non-buyers on weekly alcohol consumption or the amount of alcohol consumed the day before their latest hangover. However, buyers do report a significantly higher overall hangover severity score when compared to non-buyers. Except for vomiting and anxiety, buyers also score significantly higher on each of the individual hangover symptom severity scores.

Most commonly reported motives for buying an effective hangover treatment were “I suffer from severe hangovers, so this product is welcome” (40.5%) and “it may help to be productive the day after drinking” (24.8%). Most commonly reported motives for not buying an effective hangover treatment were “the hangover is a part of the drinking experience. I have to bear the consequences” (23.6%), “I am afraid I would drink more alcohol/the hangover prevents me from drinking more alcohol” (21.8%), “I do not suffer that much from hangovers” (15.5%), and “I do not want to use chemical/synthetic products, only natural treatments” (12.7%). Those who did not made a choice stated “would only use it if adverse effects are known and safety proven” (32.2%), “if the price of the product is reasonable” (13.6%), and “I would only use it if the product consists of natural ingredients” (12.7%). As these motives were voluntarily listed in a comment box and not specifically asked for, the percentages should be interpreted as illustrative only.

Impact on alcohol consumption

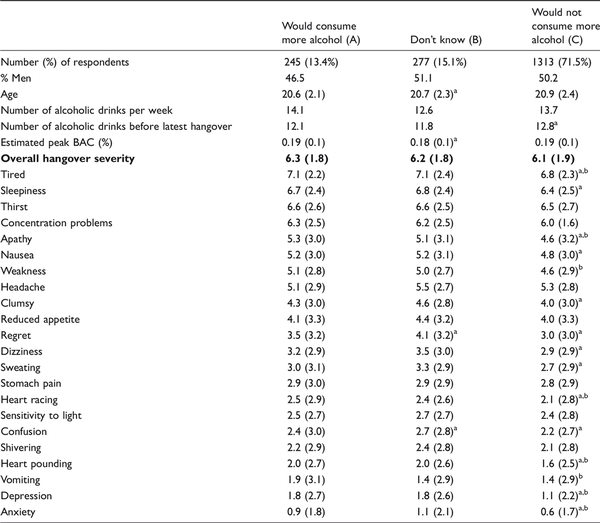

When asked whether drinkers would consume more alcohol if an effective hangover treatment was available only 13.4% answered “yes”. The vast majority answered “no” (71.6%) and 15.1% did not know. A comparison between these three groups regarding demographics, drinking characteristics, and hangover experience is summarized in Table 3.

Drinkers who answered “yes” consumed significantly less alcohol during the latest hangover session when compared to drinkers who said “no” to the question whether an effective hangover treatment would increase their alcohol consumption (p = 0.03, 12.1 versus 12.8 alcoholic drinks). Alternatively, drinkers who answered “yes” report significantly more weekly alcohol consumption when compared to drinkers who said “no” to the question whether an effective hangover treatment would increase their alcohol consumption (p = 0.05, 14.1 versus 13.7 alcoholic drinks). As the differences are less than one alcoholic drink (−0.7 and +0.5 drink, respectively), the relevance of these differences is unclear.

No significant difference in overall hangover severity was found between groups categorized with regard to whether an effective hangover product would increase their alcohol consumption. Also, severity of the majority of hangover symptoms did not differ between those who reported that they would consume more alcohol and those who do not.

An invitation to take part in a follow-up survey was send to N = 950 of the participants (those who provided their email in the original survey). Approximately half of them completed the follow-up survey (N = 471, 49.6%). Of these, N = 56 (11.9%) reported they would consume more alcohol if an effective hangover treatment was available, N = 331 (70.3%) reported they would not drink more alcohol, and N = 84 (17.8%) did not know. The responses given by the follow-up sample to the two questions did not differ significantly with the answer distribution, gender, or age of the original full sample that was surveyed. These participants were specifically asked why they would or would not consume more alcohol when an effective hangover treatment was available.

Primary motives for consuming more alcohol if an effective treatment was available were “I currently drink less alcohol because of the risk of having an alcohol hangover” (57.8%) and “I currently drink less alcohol because the hangover reduces my productivity” (28.9%). For those stating not to consume more alcohol, main reasons were “The risk of having a hangover does not influence my drinking behavior” (24.2%), “alcohol is a harmful substance” (20.3%), “I do not want to become more drunk than I already am when drinking” (18.2%), “I can not consume more alcohol than I already do” (11.7%), “I consume alcohol to have a good time, so no reason to increase the amount” (10.9%), and “I am happy with the amount of alcohol I currently consume” (7.8%). Those who do not know if an effective hangover treatment will affect their drinking behavior stated to be not sure because “alcohol is harmful” (22.2%), “it is tempting to drink more alcohol if there are no negative consequences” (18.3%), and “because the hangover prevents excessive alcohol consumption” (15.1%).

Discussion

One of the ongoing concerns, regarding potential effective hangover treatment is the idea that drinkers may increase their alcohol consumption once such a product becomes available. The current study reveals, however, that this concern may be unjustified. Although the vast majority of social drinkers confirm that they are interested in using such a product, at the same time they attest that using it will not increase their alcohol consumption.

From the analysis it became clear that the risk of having a hangover does not appear to influence drinking behavior. Drinkers did, however, attest that they were not planning to increase their alcohol consumption as alcohol is a harmful substance and they do not want to become more drunk than they already are when drinking. Alcohol consumption is viewed as part of a social gathering and has the purpose to have a good time. Hence, most drinkers are happy with the current amount of alcohol they consume and have no reason to increase this amount.

In contrast, those who state that a hangover cure might make them drink more alcohol explained their decision by the fact that they currently moderate their alcohol consumption to prevent having a hangover, including the risk of reduced productivity. This idea is supported by drinkers who are unsure about the effect on their drinking behavior who stated that an effective hangover cure would make it tempting to increase their alcohol consumption. Although one can argue that it is a minority of drinkers who held these views, they still represent a substantial number of drinkers.

When looking at the amount of alcohol consumed prior to their latest hangover, all groups (hangover cure buyers versus non-buyers and users versus non-users) show comparable alcohol consumption levels (around 12 units, reaching an estimated peak BACs around 0.19%) that are significantly unhealthy. In terms of prevention and education, this type of heavy alcohol use deserves attention per se. The findings of this study are supported by a recent naturalistic study () where similar amounts of alcohol were consumed resulting in a comparable estimated peak BAC. In general, for health reasons moderation of alcohol consumption should be advocated, and plans to further increase alcohol consumption should be discouraged.

The study has several limitations that need to be addressed. First, the sample that completed the survey were young volunteers, aged 18 to 30 years old. While this is a population that is overrepresented in those indulging in heavy drinking and experiencing hangovers, it is not known from the current data if older adults and elderly drinkers would have similar views. Second, as we asked for respondents’ intentions regarding future behavior, the current data does not prove that this behavior would actually materialize. In this context it should be noted that the intentions of our respondents contrasted with the observation made by who found reduced alcohol intake the day after having a severe hangover. To further investigate the potential protective effects of having hangovers with regard to future alcohol intake, prospective studies should be conducted to demonstrate that the use of an effective hangover treatment would indeed not affect drinking behavior of the vast majority of social drinkers.

Finally, the data clearly show there is an interest for an effective hangover treatment. The most mentioned motives to buy such a product were to prevent experiencing hangover symptoms and to increase productivity the day after heavy alcohol consumption. Only 5% of participants chose the option to prefer consuming less alcohol as alternative means to prevent the alcohol hangover and its functional consequences. Those who said they would to buy a hangover treatment do not differ in alcohol consumption or hangover experience from those who were not interested in buying a hangover treatment. The latter implies that other factors than alcohol consumption are important when making this decision. In this regard, the willingness of drinkers to use chemical or synthetic products as opposed to natural products, pricing, and whether possible adverse effects of using the product are known and its safety is proven were mentioned as relevant.

References

- Frone MR (2006) Prevalence and distribution of alcohol use and impairment in the workplace: A U.S. national survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 67: 147–156.

- Gjerde H, Christophersen AS, Moan IS, et al(2010) Use of alcohol and drugs by Norwegian employees: A pilot study using questionnaires and analysis of oral fluid. Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology 5: 13.

- Hogewoning A, Van de Loo AJAE, Mackus M, et al(2016) Characteristics of social drinkers with and without a hangover after heavy alcohol consumption. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation 7: 161–167.

- Huntley G, Treloar H, Blanchard A, et al(2015) An event-level investigation of hangovers’ relationship to age and drinking. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology 23: 314–323.

- Kim J, Chung W, Lee S, et al(2010) Estimating the socioeconomic costs of alcohol drinking among adolescents in Korea. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health 43: 341–351.

- Mallett KA, Lee CM, Neighbors C, et al(2006) Do we learn from our mistakes? An examination of the impact of negative alcohol-related consequences on college students’ drinking patterns and perceptions. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 67: 269–276.

- Roche A, Pidd K, Kostadinov V (2016) Alcohol- and drug-related absenteeism: A costly problem. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 40(3): 236–238.

- Roche AM, Pidd K, Berry JG, et al(2008) Workers’ drinking patterns: The impact on absenteeism in the Australian work-place. Addiction 103: 738–748.

- Rohsenow DJ, Howland J, Winter M, et al(2012) Hangover sensitivity after controlled alcohol administration as predictor of post-college drinking. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 121(1): 270–275.

- Stephens R, Grange JA, Jones K, et al(2014) A critical analysis of alcohol hangover research methodology for surveys or studies of effects on cognition. Psychopharmacology 231(11): 2223–2236.

- Verster JC (2012) The need for an effective hangover cure. Current Drug Abuse Reviews 5: 1–2.

- Verster JC, Bervoets AC, de Klerk S, et al(2014a) Effects of alcohol hangover on simulated highway driving performance. Psychopharmacology 231(15): 2999–3008.

- Verster JC, Penning R (2010) Treatment and prevention of alcohol hangover. Current Drug Abuse Reviews 3(2): 103–109.

- Verster JC, Bervoets AC, de Klerk S, et al(2014a) Effects of alcohol hangover on simulated highway driving performance. Psychopharmacology 231(15): 2999–3008.

- Verster JC, van der Maarel M, McKinney A, et al(2014b) Driving during alcohol hangover among Dutch professional truck drivers. Traffic Injury Prevention 15(5): 434–438.

- Watson PE, Watson ID, Batt RD (1981) Prediction of blood alcohol concentrations in human subjects. Updating the Widmark Equation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 42: 547–556.