Table of content

List of abbreviations 252

Definition of preventive cardiology 252

Preventive cardiology–towards a sub-specialty of cardiology 252

The concept of the core curriculum for preventive cardiology 253

1. CanMEDS roles 255

2. Clinical competencies 255

3. Entrustable professional activities 255

4. Level of independence 257

5. Assessment of clinical competences using EPAs 258

Sources of knowledge in preventive cardiology 258

Chapter 1: Population science and public health 258

1.1 Design, implement and evaluate preventive interventions at the population level 258

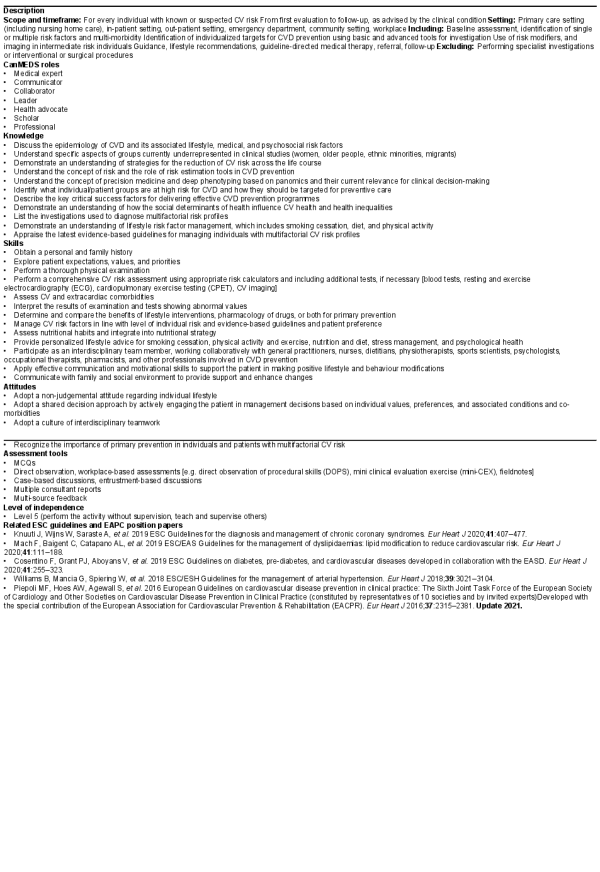

Chapter 2: Primary prevention and risk factor management 260

2.1 Manage individuals with multifactorial cardiovascular risk profiles 260

2.2 Manage a patient with non-traditional cardiovascular risk factors 261

Chapter 3: Secondary prevention and rehabilitation 263

3.1 Manage a prevention and rehabilitation programme for a cardiovascular patient 263

3.2 Manage a prevention and rehabilitation programme for a cardiovascular patient with significant comorbidities, frailty, and/or cardiac devices 265

3.3 Manage a cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation programme for an oncology patient 267

Chapter 4: Sports cardiology and exercise 268

4.1 Manage pre-participation screening in a competitive athlete 268

4.2 Manage the work-up of an athlete with suspected or known cardiovascular disease 270

Chapter 5: Cardiopulmonary exercise testing 271

5.1 Use cardiopulmonary exercise testing for diagnosis, risk stratification and exercise prescription 271

List of abbreviations

6MWT6-min walk test

AHAAmerican Heart Association

ACCAmerican College of Cardiology

CIEDCardiac implantable electrical devices

CVDCardiovascular disease

CVCardiovascular

CPETCardiopulmonary exercise testing

DOPSDirect observation of procedural skills

EAPCEuropean Association for Preventive Cardiology

EBSCEuropean Board for the Specialty of Cardiology

ECGElectrocardiogram

EPAEntrustable professional activity

ESCEuropean Society of Cardiology

LVADLeft ventricular assist device

Mini-CEXMini clinical evaluation exercise

MCQMultiple choice question

PPEPre-participation evaluation

Definition of preventive cardiology

Preventive cardiology encompasses the whole spectrum of cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention, at individual and population level, through all stages of life.

This includes promotion of cardiovascular (CV) health, management of individuals at risk of developing CVD, and management of patients with established CVD, through interdisciplinary care in different settings.

Preventive cardiology addresses all aspects of CV health in the context of the social determinants of health, including physical activity, exercise, sports, nutrition, weight management, smoking cessation, psychosocial factors and behavioural change, environmental, genetic and biological risk factors, and CV protective medications.

Preventive cardiology—towards a sub-specialty of cardiology

Scientific advances have led to a substantial decline of death from CVD over the last decades. However, CVD morbidity remains high and CVD are still the most common cause of death across European Society of Cardiology (ESC) member countries. While positive trends have been observed for medical management of arterial hypertension and dyslipidaemias, the prevalence of obesity has more than doubled and the prevalence of diabetes mellitus has tripled in Europe. More recent declines in the age-standardized incidence of CVD across ESC member countries have been small or absent. The incidence of CVD’s major components, ischaemic heart disease, and stroke, have both shown a downward trend but changes in prevalence have been small. In a European Heart Network study, CVD was estimated to cost the European Union economy 210 billion Euro a year in 2015, of which 53% (111 billion Euro) was due to healthcare costs.

The cardiology community has started a transition from predominantly treatment to prevention of CVD. A large body of scientific evidence has been generated and appropriate guidelines and position papers are available in the four domains of preventive cardiology: Population science and public health,, primary prevention and risk factor management,, secondary prevention and cardiovascular rehabilitation,, and sports cardiology and exercise. The European Association for Preventive Cardiology (EAPC) has recently started centre accreditation in these domains to standardize and optimize care.

Historically, CV prevention has been classified into primordial prevention (population-based measures to prevent risk factor development), primary prevention (management of individuals without clinically manifest disease but at risk of developing CVD, with the aim of delaying or preventing the onset of disease), and secondary prevention (focusing on people with established CVD). While preventive measures indeed differ in various ways for these three categories, this Task Force also acknowledges that CV risk is a continuum and that several measures to enhance CV health are applicable across the spectrum of CV prevention. Moreover, the distinction between primary and secondary prevention, albeit well-established, may in certain occasions be artificial; while people with subclinical disease (e.g. evidence of advanced atherosclerosis by imaging, but not yet with clinically manifest CVD) would formally belong to ‘primary prevention’, they often qualify for interventions applicable to the ‘secondary prevention’ setting.

Both in high-, middle-, and low-income countries, nine potentially modifiable health behaviours and CV risk factors account for most of the population attributable risk of myocardial infarction and stroke in both sexes and at all ages., Smoking, physical inactivity, unhealthy nutrition patterns, obesity, psychosocial factors, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemias, and arterial hypertension are key targets for lifestyle interventions, and optimization of medical therapy. In addition, biomarkers and genetics risk scores have the potential to further characterize individual CVD risk profiles. Beyond traditional risk factors, other drivers of residual CV risk have come to the forefront, including inflammatory, pro-thrombotic, and metabolic pathways that contribute to recurrent events and are often unrecognized and not addressed in clinical practice.

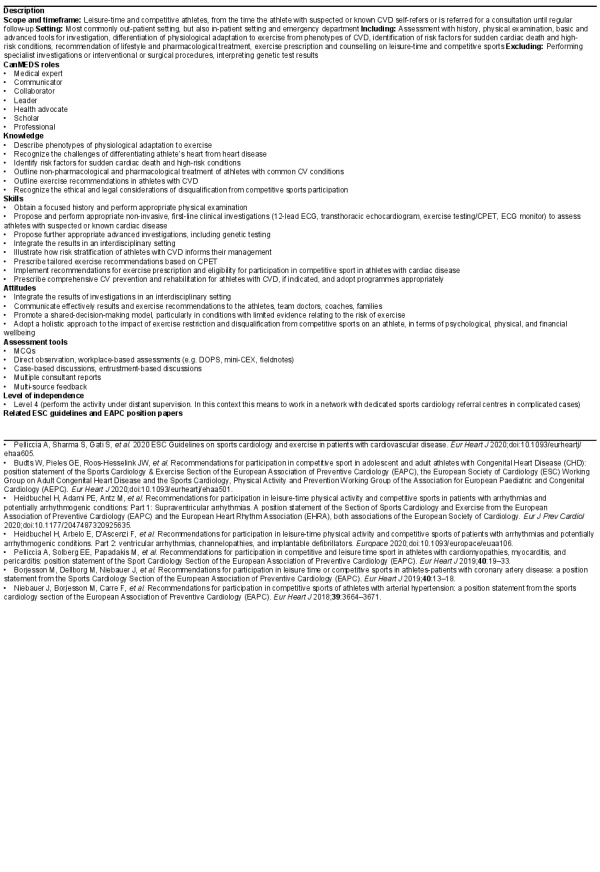

The increasing rates of obesity and diabetes, the suboptimal lifestyle management and implementation of guideline-directed medical therapy in secondary prevention of CVD, and the gaps in evidence highlight the need for further investment in preventive cardiology. The level of profound knowledge, specialized skills, and committed attitudes goes beyond core cardiology training and justifies sub-specialty training. In addition to expertise in a single CVD risk factor (e.g. diagnosis and management of dyslipidaemias), competencies are required to evaluate and manage single risk factors in the individual’s overall risk profile, take environmental, genetic, lifestyle and psychosocial aspects into account, integrate guideline-directed medical therapy, and propose a holistic management plan including attainable and realistic short-, mid-, and long-term goals. Motivational interviewing skills are required to gain the patient’s willingness to adhere to lifestyle changes and guideline-directed medical therapies in order to reach these goals. Leadership and communication skills are required to cooperate with interdisciplinary healthcare teams and other partners. Beside classical patient groups (individuals with CV risk factors, patients after acute coronary syndromes, or with chronic coronary syndromes, heart failure, implantable devices, peripheral artery disease), preventive cardiology can contribute to CV risk factor management in different patient populations, e.g. diabetes, atrial fibrillation, and cancer., Moreover, specific aspects of sports cardiology will have to be covered (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Preventive cardiology—domains, necessary competencies, and cooperation partners. CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise testing; CV, cardiovascular.

As a sub-specialty, a broader perspective of CVD prevention is necessary. Pregnancy, infancy, adolescence, early adulthood, adult and elderly life are distinct periods with individual potential opportunities for prevention. Pre-conception and pregnancy are important phases for the next generation, while post-mortem autopsy may reveal relevant information for living relatives (Figure 2). Precision medicine and digital health start to play a role in CVD prevention and have the potential to improve phenotyping of patients for more personalized and tailored therapies, and better outcomes., Emerging concepts inform new collaborations in the future and an expansion of the field of preventive cardiology.

Figure 2

Lifelong cardiovascular disease prevention from the cradle to the grave and beyond.

A common European core curriculum for preventive cardiology will help to standardize, structure, deliver, and evaluate training of cardiologists in preventive cardiology across Europe. This will be the basis for dedicated fellowship programmes and an EAPC sub-specialty certification, contributing to improvements of quality and outcome in CVD prevention. Similar initiatives have been launched in the USA. In the evolving field of preventive cardiology, the core curriculum will have to be updated at regular intervals to include emerging concepts and new scientific evidence.

The concept of the core curriculum for preventive cardiology

The changing nature of our profession and the changing environment of healthcare has led to specific requirements in the field of cardiology. In 2007, the European Board for the Specialty of Cardiology (EBSC) published recommendations for sub-specialty accreditation in cardiology. A sub-specialty is defined as a specific field of cardiology, where knowledge and skills go beyond the basic requirements of general cardiology and additional training is necessary. Sub-specialty training should be based on a published core curriculum. The core curriculum should include a formal education plan intended to bring expected learning outcomes. It should include the rationale, aims, and objectives, expected learning outcomes, education content, teaching and learning strategies, and assessment procedures.

Over the last decades, sub-specialty curricula have been developed and published by most ESC associations (Acute Cardiovascular Care, Arrhythmias & Cardiac Pacing, Heart Failure, Cardiovascular Imaging, Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions). In the field of preventive cardiology, the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) published a competence and training statement in 2009. More recent proposals for sports cardiology qualification are available from the ACC and EAPC.,

This document is the first common European core curriculum for preventive cardiology, covering all aspects of the field, including prevention, rehabilitation, and sports cardiology. It should serve as a framework for the sub-specialty qualification of cardiologists in preventive cardiology. The description of practical educational programmes, requirements for training centres and trainers is out of the scope of this document, and will be addressed in future documents. Advanced competencies in sports cardiology may be required in dedicated referral centres, addressed by a specific additional curriculum.

A core curriculum task force was established in 2019, including members of the EAPC Education Committee, the EAPC Board, and the EAPC Young Community. A writing group, including representatives of the four EAPC sections contributed to the drafting of the entrustable professional activities (EPAs). Their views and comments were captured in an iterative process employing teleconferences, in-person discussions, an online Delphi survey, and workshops at EAPC meetings.

The document was developed in cooperation with the task force of the ESC Core Curriculum for the Cardiologist. Key competencies from the field of preventive cardiology are important for core cardiology training and covered in Chapter 8 on prevention, rehabilitation, and sports. This chapter was used during the drafting process of this document, and served as a guideline to harmonize structure and content. The intention of this core curriculum is to describe the additional knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary for sub-specialty qualification in preventive cardiology. The final document was approved by the EAPC Board in October 2020, and reviewed by the ESC Education Committee.

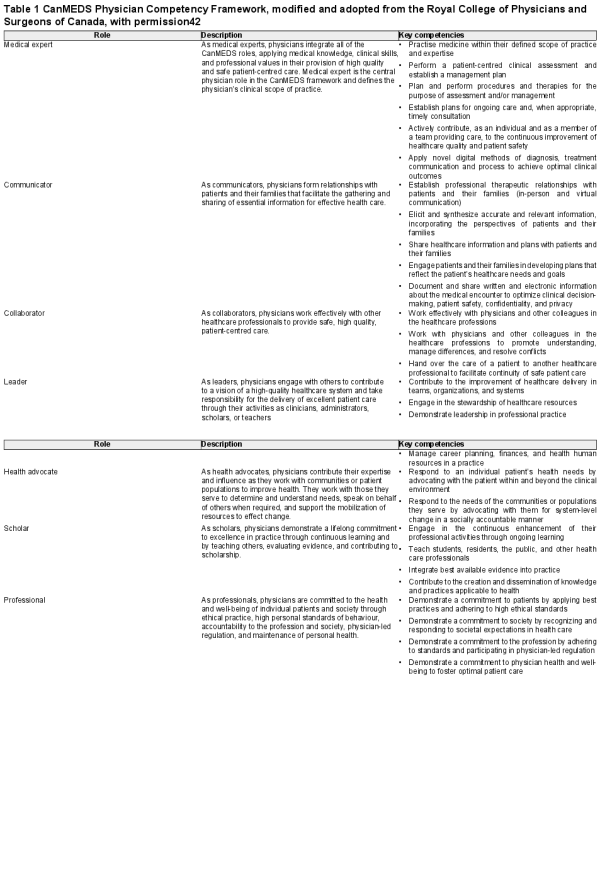

1. CanMEDS roles

The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada have produced a widely accepted standard framework of physician roles, CanMEDS. This framework was built to identify and describe the abilities physicians require to effectively meet the healthcare needs of the people they serve (Table 1). The ESC has adopted the CanMEDS roles in the ESC Core Curriculum for the Cardiologist.

CanMEDS roles can be assessed and taught individually, and they are all represented to a different extend in each of the EPAs of the Core Curriculum for Preventive Cardiology as outlined in Chapters 1–5. While EPAs are proposed as the preferred method of assessing specialty competencies, the CanMEDS roles can be viewed as generic competencies of physicians.

In the field of preventive cardiology, physicians work in interdisciplinary teams and the scope of cardiovascular prevention goes beyond patient care. Thus, the CanMEDs roles of communicator, collaborator, and health advocate are of particular importance.

2. Clinical competencies

The conceptualization, organization, and administration of preventive cardiology involves different groups of healthcare professionals. In the context of this curriculum, we focus on the competences of the cardiologist to administer of preventive cardiology in clinical practice.

In addition to the clinical competencies acquired during core cardiology training, the sub-specialty of preventive cardiology requires specific knowledge, skills and appropriate attitudes in primary prevention, risk factor assessment and management, population science, public health, secondary prevention, rehabilitation, sports cardiology, and exercise testing and training.

The number of clinical competencies calls for assessment throughout sub-specialty training. Within the process of continuous professional development, this may encourage continuous learning which will continue after sub-specialist certification. To enable these goals, the core curriculum consists of EPAs (see below). To make knowledge accessible, each EPA contains a detailed map linking to contemporary guidelines and position papers and the ESC topic list, thereby enabling cross-linking with knowledge and training databases including textbooks, structured and case-based learning courses, congress programmes, and online materials.

3. Entrustable professional activities

Trust is not only central for the relationship between trainers and trainees, but also in the shared decision-making process between physicians and their patients, and in the interaction with other healthcare professionals. An EPA is a key task of a discipline that an individual can be trusted to perform in a given healthcare context, once sufficient competence has been demonstrated. The EPA concept allows trainers to make competency-based decisions about the level of supervision required by trainees. Competency-based education targets standardized levels of proficiency to guarantee that all learners have a sufficient level of proficiency at the completion of training. EPAs are not an alternative for competencies, but a means to translate competencies into clinical practice. While competencies are descriptors of physicians, EPAs are descriptors of work. EPAs usually require multiple competencies in an integrative holistic nature. EPAs are observable and measurable and can be mapped to competencies and milestones across the entire landscape of physician activities. They can be monitored, documented, and certified.

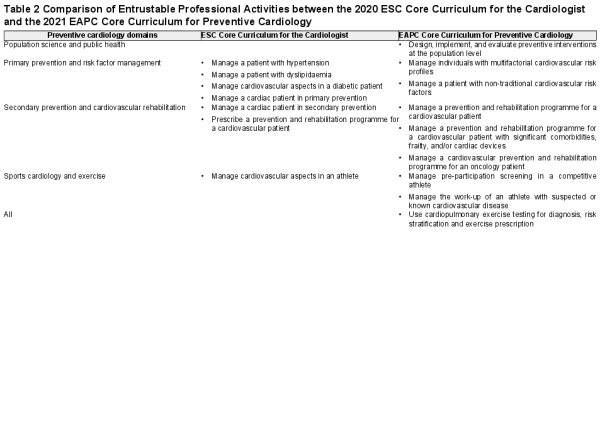

The American Board of Pediatrics was one of the first certifying agencies that introduced the concept of EPAs in their revised training guideline for the sub-specialty of paediatric cardiology in 2015. The ESC has introduced EPAs in the 2020 update of the ESC Core Curriculum for the Cardiologist, containing one chapter on prevention, rehabilitation, and sports with seven EPAs.

The nine EPAs of the EAPC Core Curriculum for Preventive Cardiology describe the additional competencies necessary for the sub-specialty of preventive cardiology and are grouped in chapters, according to specific domains of preventive cardiology (Table 2).

All EAPC sections were involved in the definition of the content. The EPA 2.2 Manage a patient with non-traditional cardiovascular risk factors, builds upon the competencies required for EPA 2.1 Manage individuals with multifactorial cardiovascular risk profiles, and the knowledge, skills, and attitude sections emphasize additional and particularly relevant aspects only. The same applies to EPA 3.2 Manage a prevention and rehabilitation programme for a cardiovascular patient with significant comorbidities, frailty, and/or cardiac devices, and EPA 3.1 Manage a prevention and rehabilitation programme for a cardiovascular patient. The EPA 5.1 Use cardiopulmonary exercise testing for diagnosis, risk stratification and exercise prescription, deals with a testing modality, specific for preventive cardiology, since independent execution and interpretation is not required during core cardiology training. This EPA is relevant in all domains of preventive cardiology.

All EPAs of this core curriculum share a common structure. The clinical competence is defined in the title, followed by a description of scope and timeframe, setting, including and excluding situations and procedures. Relevant roles of the CanMEDS Physician Competency Framework are mentioned. Knowledge, skills, and attitudes are formulated as learning outcomes, and assessment tools are recommended. The required level of independence is mentioned. Related ESC Guidelines and EAPC Position Papers are included as primary sources of knowledge. Relevant topics from the ESC topic list for each EPA are summarized in a Supplementary material online, File.

4. Level of independence

The level of entrustment or independence for executing an EPA will change during the training period (Table 3). At a certain time of the training, trainees may have different levels of independence in different EPAs. Given the broad spectrum of CVD prevention, sub-specialty training is not intended to achieve level of independence of five in all nine EPAs. For the following three EPAs, a lower level of independence is recommended.

1.1 Design, implement and evaluate preventive interventions at the population level (level 3)

2.2 Manage a patient with non-traditional cardiovascular risk factors (level 4)

4.2 Manage the work-up of an athlete with suspected or known cardiovascular disease (level 4)

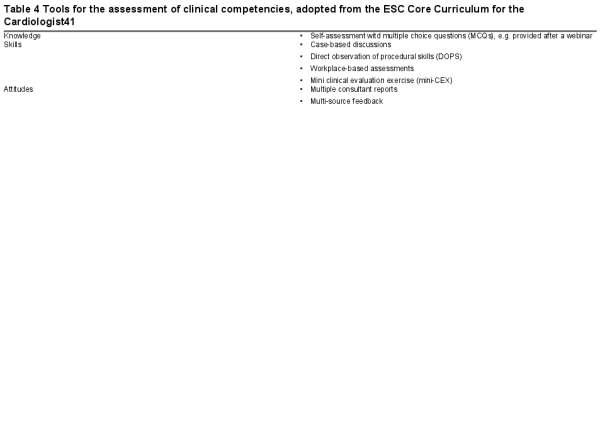

5. Assessment of clinical competences using EPA’s

One important aspect in the concept of EPAs is the assessment of clinical competencies. EPAs provide a framework for trainers to perform easy, formative and repeated assessments of trainees during their sub-specialty training, which help to adjust the trainee’s level of independence. Optimally, these assessments should be integrated into routine clinical care. The competencies of the trainees will further increase after completing the training in line with their continuous professional development. Consulting more experienced colleagues or other experts in complex cases should not be judged as need for supervision, but as a clinical reality in times of rapid increasing medical knowledge. When a trainee is able to execute an EPA in routine cases in an independent manner and to assume the expected professional responsibilities, the highest level of independence is achieved.

Suitable tools for the assessment of EPAs depend on the nature of the activity and are proposed in the assessment section of each EPA (Table 4).

Sources of knowledge in preventive cardiology

In addition to specific guidelines and position papers provided at the end of each EPA, the ESC has published four textbooks in the field of preventive cardiology as additional source of comprehensive knowledge.

ESC Textbook of Preventive Cardiology 2015

ESC Handbook of Preventive Cardiology 2016

ESC Textbook of Sports Cardiology 2019

ESC Handbook of Cardiovascular Rehabilitation 2020

Chapter 1: Population science and public health

1.1 Design, implement and evaluate preventive interventions at the population level

Chapter 2: Primary prevention and risk factor management

2.1 Manage individuals with multifactorial cardiovascular risk profiles

2.2 Manage a patient with non-traditional cardiovascular risk factors

Chapter 3: Secondary prevention and rehabilitation

3.1 Manage a prevention and rehabilitation programme for a cardiovascular patient

3.2 Manage a prevention and rehabilitation programme for a cardiovascular patient with significant comorbidities, frailty, and/or cardiac devices

3.3 Manage a cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation programme for an oncology patient

Chapter 4: Sports cardiology and exercise

4.1 Manage pre-participation evaluation in a competitive athlete

4.2 Manage the work-up of an athlete with suspected or known cardiovascular disease

Chapter 5: Cardiopulmonary exercise testing

5.1 Use cardiopulmonary exercise testing for diagnosis, risk stratification and exercise prescription

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Journal of Preventive Cardiology online.

Conflict of interest: MP received research grants from the charitable organisation Cardiac Risk in the Young which supports cardiac screening of young individuals. No other author declared a conflict of interest in the context of this core curriculum.

References

- 1. Nabel EG, Braunwald E. A tale of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med2012;366:54–63.

- 2. Timmis A, Townsend N, Gale CP, Torbica A, Lettino M, Petersen SE, Mossialos EA, Maggioni AP, Kazakiewicz D, May HT, De Smedt D, Flather M, Zuhlke L, Beltrame JF, Huculeci R, Tavazzi L, Hindricks G, Bax J, Casadei B, Achenbach S, Wright L, Vardas P; European Society of Cardiology. European Society of Cardiology: cardiovascular disease statistics 2019. Eur Heart J2020;41:12–85.

- 3. Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, Cooney MT, Corrà U, Cosyns B, Deaton C, Graham I, Hall MS, Hobbs FDR, Løchen ML, Löllgen H, Marques-Vidal P, Perk J, Prescott E, Redon J, Richter DJ, Sattar N, Smulders Y, Tiberi M, van der Worp HB, van Dis I, Verschuren WMM, Binno S; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J2016;37:2315–2381.

- 4. Arena R, Guazzi M, Lianov L, Whitsel L, Berra K, Lavie CJ, Kaminsky L, Williams M, Hivert M-F, Cherie Franklin N, Myers J, Dengel D, Lloyd-Jones DM, Pinto FJ, Cosentino F, Halle M, Gielen S, Dendale P, Niebauer J, Pelliccia A, Giannuzzi P, Corra U, Piepoli MF, Guthrie G, Shurney D, Arena R, Berra K, Dengel D, Franklin NC, Hivert M-F, Kaminsky L, Lavie CJ, Lloyd-Jones DM, Myers J, Whitsel L, Williams M, Corra U, Cosentino F, Dendale P, Giannuzzi P, Gielen S, Guazzi M, Halle M, Niebauer J, Pelliccia A, Piepoli MF, Pinto FJ, Guthrie G, Lianov L, Shurney D. Healthy lifestyle interventions to combat noncommunicable disease-a novel nonhierarchical connectivity model for key stakeholders: a policy statement from the American Heart Association, European Society of Cardiology, European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation, and American College of Preventive Medicine. Eur Heart J2015;36:2097–2109.

- 5. Jørgensen T, Capewell S, Prescott E, Allender S, Sans S, Zdrojewski T, De Bacquer D, de Sutter J, Franco OH, Løgstrup S, Volpe M, Malyutina S, Marques-Vidal P, Reiner Ž, Tell GS, Verschuren WMM, Vanuzzo D. Population-level changes to promote cardiovascular health. Eur J Prev Cardiol2013;20:409–421.

- 6. Cosentino F, Grant PJ, Aboyans V, Bailey CJ, Ceriello A, Delgado V, Federici M, Filippatos G, Grobbee DE, Hansen TB, Huikuri HV, Johansson I, Jüni P, Lettino M, Marx N, Mellbin LG, Östgren CJ, Rocca B, Roffi M, Sattar N, Seferović PM, Sousa-Uva M, Valensi P, Wheeler DC; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur Heart J2020;41:255–323.

- 7. Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, Koskinas KC, Casula M, Badimon L, Chapman MJ, De Backer GG, Delgado V, Ference BA, Graham IM, Halliday A, Landmesser U, Mihaylova B, Pedersen TR, Riccardi G, Richter DJ, Sabatine MS, Taskinen MR, Tokgozoglu L, Wiklund O; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J2020;41:111–188.

- 8. Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, Clement DL, Coca A, de Simone G, Dominiczak A, Kahan T, Mahfoud F, Redon J, Ruilope L, Zanchetti A, Kerins M, Kjeldsen SE, Kreutz R, Laurent S, Lip GYH, McManus R, Narkiewicz K, Ruschitzka F, Schmieder RE, Shlyakhto E, Tsioufis C, Aboyans V, Desormais I; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J2018;39:3021–3104.

- 9. Ambrosetti M, Abreu A, Corra U, Davos CH, Hansen D, Frederix I, Iliou MC, Pedretti RF, Schmid JP, Vigorito C, Voller H, Wilhelm M, Piepoli MF, Bjarnason-Wehrens B, Berger T, Cohen-Solal A, Cornelissen V, Dendale P, Doehner W, Gaita D, Gevaert AB, Kemps H, Kraenkel N, Laukkanen J, Mendes M, Niebauer J, Simonenko M, Zwisler AO. Secondary prevention through comprehensive cardiovascular rehabilitation: From knowledge to implementation. 2020 update. A position paper from the Secondary Prevention and Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol2020;doi:10.1177/2047487320913379.

- 10. Scherrenberg M, Wilhelm M, Hansen D, Völler H, Cornelissen V, Frederix I, Kemps H, Dendale P. The future is now: a call for action for cardiac telerehabilitation in the COVID-19 pandemic from the secondary prevention and rehabilitation section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol2020;doi:10.1177/2047487320939671.

- 11. Kemps H, Kränkel N, Dörr M, Moholdt T, Wilhelm M, Paneni F, Serratosa L, Ekker Solberg E, Hansen D, Halle M, Guazzi M. Exercise training for patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease: What to pursue and how to do it. A Position Paper of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC). Eur J Prev Cardiol2019;26:709–727.

- 12. Hansen D, Kraenkel N, Kemps H, Wilhelm M, Abreu A, Pfeiffer AF, Jordão A, Cornelissen V, Völler H. Management of patients with type 2 diabetes in cardiovascular rehabilitation. Eur J Prev Cardiol2019;26:133–144.

- 13. Vigorito C, Abreu A, Ambrosetti M, Belardinelli R, Corrà U, Cupples M, Davos CH, Hoefer S, Iliou M-C, Schmid J-P, Voeller H, Doherty P. Frailty and cardiac rehabilitation: a call to action from the EAPC Cardiac Rehabilitation Section. Eur J Prev Cardiol2017;24:577–590.

- 14. Piepoli MF, Conraads V, Corrà U, Dickstein K, Francis DP, Jaarsma T, McMurray J, Pieske B, Piotrowicz E, Schmid J-P, Anker SD, Solal AC, Filippatos GS, Hoes AW, Gielen S, Giannuzzi P, Ponikowski PP. Exercise training in heart failure: from theory to practice. A consensus document of the Heart Failure Association and the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Eur J Heart Fail2011;13:347–357.

- 15. Pelliccia A, Sharma S, Gati S, Bäck M, Börjesson M, Caselli S, Collet JP, Corrado D, Drezner JA, Halle M, Hansen D, Heidbuchel H, Myers J, Niebauer J, Papadakis M, Piepoli MF, Prescott E, Roos-Hesselink JW, Graham Stuart A, Taylor RS, Thompson PD, Tiberi M, Vanhees L, Wilhelm M; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines on sports cardiology and exercise in patients with cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J2021;42:17–96.

- 16. Heidbuchel H, Papadakis M, Panhuyzen-Goedkoop N, Carré F, Dugmore D, Mellwig K-P, Rasmusen HK, Solberg EE, Borjesson M, Corrado D, Pelliccia A, Sharma S. Position paper: proposal for a core curriculum for a European Sports Cardiology qualification. Eur J Prev Cardiol2013;20:889–903.

- 17. Niebauer J, Börjesson M, Carre F, Caselli S, Palatini P, Quattrini F, Serratosa L, Adami PE, Biffi A, Pressler A, Schmied C, van Buuren F, Panhuyzen-Goedkoop N, Solberg E, Halle M, La Gerche A, Papadakis M, Sharma S, Pelliccia A. Recommendations for participation in competitive sports of athletes with arterial hypertension: a position statement from the sports cardiology section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC). Eur Heart J2018;39:3664–3671.

- 18. Borjesson M, Dellborg M, Niebauer J, LaGerche A, Schmied C, Solberg EE, Halle M, Adami E, Biffi A, Carré F, Caselli S, Papadakis M, Pressler A, Rasmusen H, Serratosa L, Sharma S, van Buuren F, Pelliccia A. Recommendations for participation in leisure time or competitive sports in athletes-patients with coronary artery disease: a position statement from the Sports Cardiology Section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC). Eur Heart J2019;40:13–18.

- 19. Budts W, Pieles GE, Roos-Hesselink JW, Sanz de la Garza M, D'Ascenzi F, Giannakoulas G, Müller J, Oberhoffer R, Ehringer-Schetitska D, Herceg-Cavrak V, Gabriel H, Corrado D, van Buuren F, Niebauer J, Börjesson M, Caselli S, Fritsch P, Pelliccia A, Heidbuchel H, Sharma S, Stuart AG, Papadakis M. Recommendations for participation in competitive sport in adolescent and adult athletes with Congenital Heart Disease (CHD): position statement of the Sports Cardiology & Exercise Section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC), the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Working Group on Adult Congenital Heart Disease and the Sports Cardiology, Physical Activity and Prevention Working Group of the Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). Eur Heart J2020;41:4191–4199.

- 20. Heidbuchel H, Adami PE, Antz M, Braunschweig F, Delise P, Scherr D, Solberg EE, Wilhelm M, Pelliccia A. Recommendations for participation in leisure-time physical activity and competitive sports in patients with arrhythmias and potentially arrhythmogenic conditions: Part 1: Supraventricular arrhythmias. A position statement of the Section of Sports Cardiology and Exercise from the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC) and the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), both associations of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol2020;doi:10.1177/2047487320925635.

- 21. Heidbuchel H, Arbelo E, D'Ascenzi F, Borjesson M, Boveda S, Castelletti S, Miljoen H, Mont L, Niebauer J, Papadakis M, Pelliccia A, Saenen J, Sanz de la Garza M, Schwartz PJ, Sharma S, Zeppenfeld K, Corrado D. Recommendations for participation in leisure-time physical activity and competitive sports of patients with arrhythmias and potentially arrhythmogenic conditions. Part 2: ventricular arrhythmias, channelopathies, and implantable defibrillators. Europace2020;23:147–148.

- 22. Abreu A, Frederix I, Dendale P, Janssen A, Doherty P, Piepoli MF, Völler H, Davos CH. Standardization and quality improvement of secondary prevention through cardiovascular rehabilitation programmes in Europe: The avenue towards EAPC accreditation programme: a position statement of the Secondary Prevention and Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC). Eur J Prev Cardiol2020;doi:10.1177/2047487320924912.

- 23. Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ôunpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, McQueen M, Budaj A, Pais P, Varigos J, Lisheng L. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet2004;364:937–952.

- 24. O'Donnell MJ, Xavier D, Liu L, Zhang H, Chin SL, Rao-Melacini P, Rangarajan S, Islam S, Pais P, McQueen MJ, Mondo C, Damasceno A, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Hankey GJ, Dans AL, Yusoff K, Truelsen T, Diener H-C, Sacco RL, Ryglewicz D, Czlonkowska A, Weimar C, Wang X, Yusuf S. Risk factors for ischaemic and intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (the INTERSTROKE study): a case-control study. Lancet2010;376:112–123.

- 25. Knowles JW, Ashley EA. Cardiovascular disease: The rise of the genetic risk score. PLoS Med2018;15:e1002546.

- 26. Dhindsa DS, Sandesara PB, Shapiro MD, Wong ND. The evolving understanding and approach to residual cardiovascular risk management. Front Cardiovasc Med2020;7:88.

- 27. Kotseva K, De Backer G, De Bacquer D, Rydén L, Hoes A, Grobbee D, Maggioni A, Marques-Vidal P, Jennings C, Abreu A, Aguiar C, Badariene J, Bruthans J, Castro Conde A, Cifkova R, Crowley J, Davletov K, Deckers J, De Smedt D, De Sutter J, Dilic M, Dolzhenko M, Dzerve V, Erglis A, Fras Z, Gaita D, Gotcheva N, Heuschmann P, Hasan-Ali H, Jankowski P, Lalic N, Lehto S, Lovic D, Mancas S, Mellbin L, Milicic D, Mirrakhimov E, Oganov R, Pogosova N, Reiner Z, Stöerk S, Tokgözoğlu L, Tsioufis C, Vulic D, Wood D; on behalf of the EUROASPIRE Investigators. Lifestyle and impact on cardiovascular risk factor control in coronary patients across 27 countries: results from the European Society of Cardiology ESC-EORP EUROASPIRE V registry. Eur J Prev Cardiol2019;26:824–835.

- 28. Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Boriani G, Castella M, Dan GA, Dilaveris PE, Fauchier L, Filippatos G, Kalman JM, La Meir M, Lane DA, Lebeau JP, Lettino M, Lip GYH, Pinto FJ, Thomas GN, Valgimigli M, Van Gelder IC, Van Putte BP, Watkins CL; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J2021;42:373–498

- 29. Gilchrist SC, Barac A, Ades PA, Alfano CM, Franklin BA, Jones LW, La Gerche A, Ligibel JA, Lopez G, Madan K, Oeffinger KC, Salamone J, Scott JM, Squires RW, Thomas RJ, Treat-Jacobson DJ, Wright JS; On behalf of the American Heart Association Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Secondary Prevention Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Cardio-oncology rehabilitation to manage cardiovascular outcomes in cancer patients and survivors: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation2019;139:e997–e1012.

- 30. Zamorano JL, Lancellotti P, Rodriguez Muñoz D, Aboyans V, Asteggiano R, Galderisi M, Habib G, Lenihan DJ, Lip GYH, Lyon AR, Lopez Fernandez T, Mohty D, Piepoli MF, Tamargo J, Torbicki A, Suter TM. 2016 ESC Position Paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity developed under the auspices of the ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines: The Task Force for cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J2016;37:2768–2801.

- 31. Dendale P, Scherrenberg M, Sivakova O, Frederix I. Prevention: from the cradle to the grave and beyond. Eur J Prev Cardiol2019;26:507–511.

- 32. Leopold JA, Loscalzo J. Emerging role of precision medicine in cardiovascular disease. Circ Res2018;122:1302–1315.

- 33. Sharma A, Harrington RA, McClellan MB, Turakhia MP, Eapen ZJ, Steinhubl S, Mault JR, Majmudar MD, Roessig L, Chandross KJ, Green EM, Patel B, Hamer A, Olgin J, Rumsfeld JS, Roe MT, Peterson ED. Using digital health technology to better generate evidence and deliver evidence-based care. J Am Coll Cardiol2018;71:2680–2690.

- 34. Bairey Merz CN, Alberts MJ, Balady GJ, Ballantyne CM, Berra K, Black HR, Blumenthal RS, Davidson MH, Fazio SB, Ferdinand KC, Fine LJ, Fonseca V, Franklin BA, McBride PE, Mensah GA, Merli GJ, O'Gara PT, Thompson PD, Underberg JA; American Academy of Neurology; American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; American College of Preventive Medicine; American College of Sports Medicine; American Diabetes Association; American Society of Hypertension; Association of Black Cardiologists; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Lipid Association; Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. ACCF/AHA/ACP 2009 competence and training statement: a curriculum on prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association/American College of Physicians Task Force on Competence and Training (Writing Committee to Develop a Competence and Training Statement on Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease): developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology; American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; American College of Preventive Medicine; American College of Sports Medicine; American Diabetes Association; American Society of Hypertension; Association of Black Cardiologists; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Lipid Association; and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. Circulation2009;120:e100–e126.

- 35. Shapiro MD, Maron DJ, Morris PB, Kosiborod M, Sandesara PB, Virani SS, Khera A, Ballantyne CM, Baum SJ, Sperling LS, Bhatt DL, Fazio S. Preventive cardiology as a subspecialty of cardiovascular medicine: JACC council perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol2019;74:1926–1942.

- 36. Shapiro MD, Fazio S. Preventive cardiology as a dedicated clinical service: the past, the present, and the (Magnificent) future. Am J Prev Cardiol2020;1:100011.

- 37. Lopez-Sendon J, Mills P, Weber H, Michels R, Mario CD, Filippatos GS, Heras M, Fox K, Merino J, Pennell DJ, Sochor H, Ortoli J, Mills P, Weber H, Lopez-Sendon J, Szatmari A, Pinto F, Amlie JP, Oto A, Lainscak M, Fox K, Kearney P, Goncalves L, Huikuri H, Carrera C; Authors/Task Force Members. Recommendations on sub-specialty accreditation in cardiology: the Coordination Task Force on Sub-specialty Accreditation of the European Board for the Specialty of Cardiology. Eur Heart J2007;28:2163–2171.

- 38.

- 39. Baggish AL, Battle RW, Beckerman JG, Bove AA, Lampert RJ, Levine BD, Link MS, Martinez MW, Molossi SM, Salerno J, Wasfy MM, Weiner RB, Emery MS. Sports cardiology: core curriculum for providing cardiovascular care to competitive athletes and highly active people. J Am Coll Cardiol2017;70:1902–1918.

- 40. Ten Cate O. Nuts and bolts of entrustable professional activities. J Grad Med Educ2013;5:157–158.

- 41. Tanner FC, Brooks N, Fox KF, Gonçalves L, Kearney P, Michalis L, Pasquet A, Price S, Bonnefoy E, Westwood M, Plummer C, Kirchhof P; ESC Scientific Document Group. ESC core curriculum for the cardiologist. Eur Heart J2020;41:3605–3692.

- 42.

- 43. Ross RD, Brook M, Feinstein JA, Koenig P, Lang P, Spicer R, Vincent JA, Lewis AB, Martin GR, Bartz PJ, Fischbach PS, Fulton DR, Matherne GP, Reinking B, Srivastava S, Printz B, Geva T, Shirali GS, Weinberg P, Wong PC, Armsby LB, Vincent RN, Foerster SR, Holzer RJ, Moore JW, Marshall AC, Latson L, Dubin AM, Walsh EP, Franklin W, Kanter RJ, Saul JP, Shah MJ, Van Hare GF, Feltes TF, Roth SJ, Almodovar MC, Andropoulos DB, Bohn DJ, Costello JM, Gajarski RJ, Mott AR, Stout K, Valente AM, Cook S, Gurvitz M, Saidi A, Webber SA, Hsu DT, Ivy DD, Kulik TJ, Pahl E, Rosenthal DN, Morrow R, Mahle WT, Murphy AM, Li JS, Law YM, Newburger JW, Daniels SR, Bernstein D, Marino BS. 2015 SPCTPD/ACC/AAP/AHA training guidelines for pediatric cardiology fellowship programs. J Am Coll Cardiol2015;doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.004.

- 44.