Introduction

As the cost of healthcare has risen significantly over the past 20 years, efforts continue to move toward more cost-effective delivery. One way to accomplish this is transferring the performance of some procedures from the operating room to the office, which would theoretically result in substantial savings.

In otolaryngology, such procedures have included in-office balloon sinuplasty, transnasalesophagoscopy, and laser ablation. In addition, the safety of unsedated laser therapy as an office procedure has been documented. Moreover, Zeitels et al found that pulsed-dye laser (PDL) treatment was effective in the office treatment of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP). Because RRP tends to be multifocal and recur, patients typically undergo multiple procedures during their lifetime.

To the best of our knowledge, only one other comparison of office and operating room procedures for the treatment of RRP from a patient’s perspective has been published in the literature, but that study looked only at patient characteristics and disease severity. In this article, we describe our comparison study of hospital and patient costs, outcomes, and patient satisfaction associated with office and operating room procedures.

Patients and Methods

For this study, we identified all patients who had been treated for RRP with both an office procedure and an operating room procedure, all of which had been performed by one laryngologist (G.M.G.) at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit. Using CPT codes for office laser procedures, we identified those patients who had been treated from 2005, when our hospital purchased a PDL machine (PhotoGenica V Star, model 105004800; Cynosure; Westford, Mass.), through 2012. Initially, 26 patients met our eligibility criteria.

Each patient’s medical record was reviewed to confirm that the pathology report verified the diagnosis of RRP and to verify that each patient had undergone at least one procedure in the office and one in the operating room during his or her lifetime. The decision as to whether a patient would undergo a particular procedure in the office or the operating room was not randomized. For patients with mild to moderate RRP, the patient and physician reached a mutual agreement on the type of procedure, but for patients with a significant disease burden, the office procedure was generally not offered. The goal of our study was to compare the costs, outcomes, and patient satisfaction associated with the two types of procedure.

Office procedures

A flexible transnasal esophagoscope with a side port for the laser fiber was used for all office laser procedures. Standard office procedures included administration of topical anesthesia with tetracaine applied with pledgets and placed in the nose for 10 minutes. In addition, tetracaine was sprayed onto the vocal folds through the side port. Patients were not given any sedating medications in the office either orally or intravenously before the procedure. The length of the procedures varied according to patient tolerance, but they typically did not last more than 15 minutes.

Operating room procedures

Standard operating room technique included the use of an appropriately sized laryngoscope for exposure and removal of the papillomas with a microdebrider. All operating room procedures were performed with general anesthesia and endotracheal intubation. Each procedure typically lasted about 1 hour. Barring complications, patients were discharged home the same day. The antiviral cidofovir was not routinely injected.

Comparison of costs

To ascertain costs, we compared the itemized billing records of 6 representative patients. Our analysis looked at the costs of supplies and anesthesia, various physicians’ fees, and other variables.

Patient outcomes and satisfaction questionnaire

A 30-item questionnaire was administered to ask patients about the number, frequency, and length of their procedures, as well as time missed from work, out-of-pocket expenses, convenience, comfort, pain, factors related to voice quality, complications or adverse events, and overall satisfaction. Each question pertained to both their office experience and their operating room experience. Patients had been asked to complete their questionnaire during a regularly scheduled office visit. For those who were no longer an active patient, a questionnaire was mailed to their home. Patients also received a reminder telephone call. A failure to return a questionnaire prompted one additional mailing and another follow-up phone call.

Patients were asked to base their responses on their lifetime experiences.

Final study population

Of our original 26 patients, we were unable to contact 4 because they did not have a current working phone number, accurate address, or forwarding address; another 4 patients did not return their questionnaire after we sent one to them twice and phoned them twice; and 1 patient refused to participate. Our final study population then was made up of 17 patients—1 man and 16 women, aged 30 to 86 years (mean: 62).

Statistical analysis

A two-sample Wilcoxon test was used to examine differences between those who underwent fewer than 5 PDL procedures vs. 5 or more (n = 13 and n = 4, respectively), as well as between patients who underwent 10 or fewer operating room procedures vs. 11 or more (n = 9 and n = 8.)

With respect to the questionnaire, 24 questions solicited an ordinal response from among 2 to 4 choices, and 6 questions asked for a response based on a 10-point Likert scale. Most responses were compared with the use of a Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. For those questions that had only 2 possible answers, a McNemar test was used. For each questionnaire, total of 17 responses was deemed sufficient to achieve at least 80% power with an effect size of 0.78, which was sufficient to detect statistically significant differences.

Results

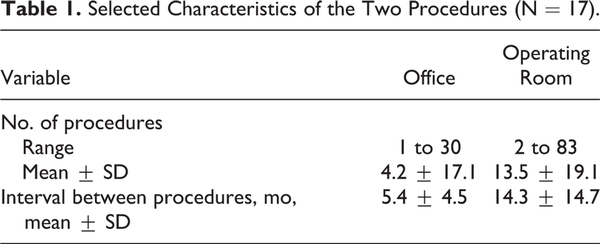

The mean number of in-office laser procedures per patient was 4.2, and the mean interval between procedures was 5.4 months (although 10 patients underwent only 1 office procedure). The mean number of operating room procedures was 13.5, and the mean interval between procedures was 14.3 months (table 1).

Costs

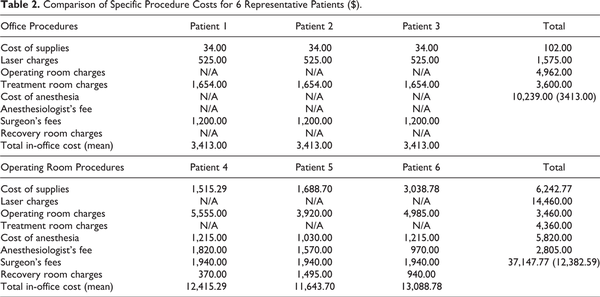

Based on the billing records of the 6 representative patients, the average hospital charges were $3,413.00 for the office procedures and $12,382.59 for the operating room procedures (table 2). The difference was $8,969.59 per patient per procedure.

Outcomes and patient satisfaction

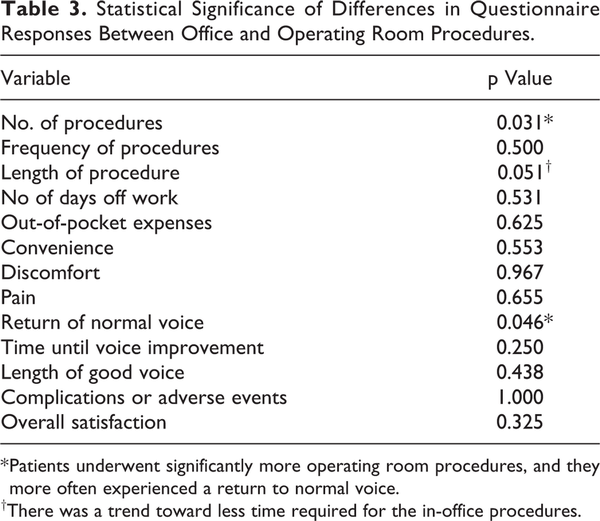

There were two statistically significant differences in outcomes: patients underwent significantly more operating room procedures (p = 0.031), and they more often experienced a return to normal voice after an office procedure (p = 0.046). In addition, office procedures tended to require less time, but the difference in procedure times did not quite reach statistical significance (p = 0.051) (table 3). When patients were asked which procedure took less time, 16 of the 17 (94.1%) said the office procedure did. When asked which of the two types of procedure cost them less in out-of-pocket expenses, 12 of 16 patients (75.0%) said the office procedure did.

No statistically significant differences in questionnaire responses were found between those patients who underwent fewer than 5 PDL procedures vs. 5 or more or between those who underwent 10 or fewer operating room procedures vs. 11 or more. Of the 13 patients who had undergone fewer than 5 office procedures, 10 had had undergone only 1 PDL procedure in their lifetime.

Five patients reported a complication or adverse event associated with an operating room procedure: 2 were related to anesthesia, 1 was a fractured crown, 1 was a taste disturbance, and 1 was unspecified. Likewise, 5 different patients reported an adverse event during an office procedure: 3 were related to anxiety, 1 was significant discomfort, and 1 was unspecified (note that we consider anxiety and discomfort to be adverse events rather than true complications). The 4 patients who experienced anxiety or discomfort all elected to undergo an operating room procedure for all subsequent treatments. The patient who reported discomfort with PDL therapy did not report that she had experienced a myocardial infarction and complicated urinary tract infection after an operating room procedure.

Discussion

Patients with chronic conditions such as RRP are ideal candidates to assess in terms of a patient’s perspective how new trends in patient care are perceived. A decision to undergo a procedure that is quicker and less expensive and one that also obviates the risks of general anesthesia would seem to be a logical one.

The average difference in the cost of office and operating room procedures in our study was nearly $9,000. In a different study by Rees et al, the difference was more than $5,000 per procedure. While these savings are quite substantial, patients on average required an office procedure three times more often than an operating room procedure, which could significantly diminish or even offset the overall savings. When taking the increased frequency of office procedures into account, the savings in our study were greatly reduced—from $10,239.00 for a single procedure to $2,143.59 for three procedures combined.

In our study, 4 of the 17 patients (23.5%) reported significant anxiety or discomfort during the PDL procedure. For the entire study group, the mean comfort score was 4.2 on a scale of 1 (no discomfort) to 10 (extreme discomfort). By contrast, Rees et al in a study similar to ours reported a comfort score of 7.4.

Rees et al also found that 87% of patients preferred office PDL to surgery in the operating room when possible. However, patients in our study did not express the same overwhelming preference. While the patients in our study were not asked directly which type of procedure they preferred, their questionnaire responses indicated that they preferred the operating room procedure. On a scale of 1 (very satisfied) to 10 (not satisfied), scores were 3.3 for the operating room procedure and 4.5 for the office PDL procedure. While this difference was not statistically significant, it did show a trend toward a preference for the operating room.

Another surprising finding in our study concerned the reporting of complications/adverse events. Four patients reported anxiety or discomfort during their office procedure; they all elected to undergo an operating room procedure for subsequent treatments of RRP. It is possible that even though patients are explained the risks of general anesthesia, they still prefer it to the discomfort of having a large scope inserted while they are awake without intravenous sedation.

Other studies have found that office procedures were associated with less pain and a quicker return to work compared with operating room procedures. Questionnaire responses in our study indicated that the rates of narcotic analgesic use and the return to work times associated with each type of procedure were similar.

One limitation of our study was its small sample size (N = 17). Also, while patients were asked to reflect on a lifetime of experiences, most of those experiences involved operating room procedures; in fact, 10 of our patients had undergone only a single PDL procedure. As a result, an inherent bias in their questionnaire responses was likely. Finally, as mentioned, patients with significant RRP were usually not offered the option of an office procedure. This is similar to what Tatar et al found, as RRP patients who underwent an operating room procedure had higher Derkay scores.

Another complicating factor of our study is that some patient responses did not match the corresponding objective data. For example, patients self-reported that the frequency with which they underwent each type of procedure was similar. However, their medical records indicated that patients underwent an office procedure three times more often than an operating room procedure.

As office procedures for RRP become more common, there will be interest in expanding their scope to include other laryngeal conditions that might require less frequent treatments, such as Reinke edema, leukoplakia, and granulomatosis. ,, Moreover, office procedures might be particularly attractive for patients who are at high risk for complications related to general anesthesia.

Because the biggest barrier to transferring a procedure from the operating room to the office is patient tolerance, steps to prevent anxiety and discomfort might be undertaken by means of better topical anesthesia or premedication with an anxiolytic. These modifications can improve comfort and allow otolaryngologists to offer an office procedure to a larger pool of patients. In addition, further studies are needed to analyze procedure cost against tumor burden, since these factors might influence the type of procedure a patient chooses.

In conclusion, our study found that while office laser procedures to treat RRP were substantially less costly per procedure than were operating room procedures, the savings were offset by the fact that the office procedures had to be performed more often.

Acknowledgment

We recognize Ed Peterson of Henry Ford Health System’s Biostatistics Department for the statistical analysis.

Authors’ Note The study described in this article was conducted at Henry Ford Hospital.

Authors’ Note Previous presentation: The information in this article has been edited for publication and updated from its original presentation as a poster at The Triological Society’s Combined Otolaryngology Spring Meetings; May 14-18, 2014; Las Vegas.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Koufman JA, Rees CJ, Frazier WD, et al. Office-based laryngeal laser surgery: A review of 443 cases using three wavelengths. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007;137(1):146–51.

- 2. Zeitels SM, Franco RA Jr, Dailey SH, et al. Office-based treatment of glottal dysplasia and papillomatosis with the 585-nm pulsed dye laser and local anesthesia. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2004;113(4):265–76.

- 3. Tatar EÇ, Kupfer RA, Barry JY, et al. Office-based vs traditional operating room management of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis: Impact of patient characteristics and disease severity. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017;143(1):55–9.

- 4. Rees CJ, Postma GN, Koufman JA. Cost-savings of unsedated office-based laser surgery for laryngeal papillomas. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2007;116(1):45–8.

- 5. Rees CJ, Halum SL, Wijewickrama RC, et al. Patient tolerance of in-office pulsed dye laser treatments to the upper aerodigestive tract. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2006;134(6):1023–7.

- 6. Franco RA Jr. In-office laryngeal surgery with the 585-nm pulsed dye laser. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007;15(6):387–93.

- 7. Franco RA Jr, Zeitels SM, Farinelli WA, et al. 585-nm pulsed dye laser treatment of glottal dysplasia. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2003;112(9 Pt 1):751–8.

- 8. Clyne SB, Halum SL, Koufman JA, Postma GN. Pulsed dye laser treatment of laryngeal granulomas. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2005;114(3):198–201.