Introduction

Most residents and young otolaryngologists are familiar with the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, Inc (AAO-HNS) guidelines for tympanostomy tubes and with the mechanics of tube placement in the operating room. This issue of the Ear, Nose, and Throat (ENT) Journal aims to provide advanced knowledge of tympanostomy tube care-based best-evidence, including both clinical studies when available, and expert opinion where high-quality research is lacking.

This article is designed as a photo essay, including images to help guide young otolaryngologists through some of the dilemmas they will encounter during a career of caring for children with tympanostomy tubes. Some of the approaches to tympanostomy tube care described are based on prospective controlled studies. As often, they reflect the collective experiences of pediatric otolaryngologists—especially of those of Charles D. Bluestone and Sylvan E. Stool, to whom the article is dedicated.

What Is Recurrent Acute Otitis Media?

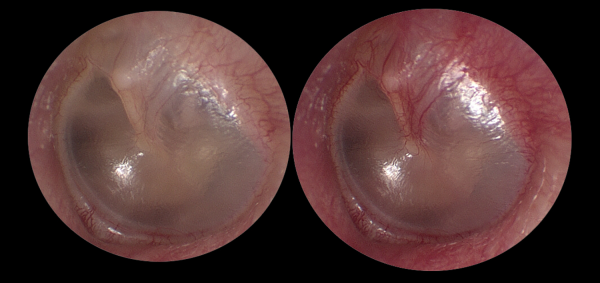

Acute otitis media (AOM) is difficult to diagnosis especially in the young, sometimes uncooperative children most commonly affected by the disease. There is no reliable patient symptom or any single physical sign that assures correct diagnosis. In a feverish, crying child, vascular engorgement can produce the “red eardrum” that might lead a pediatric provider to diagnose AOM and prescribe an antibiotic (Figure 1, video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zNv93t4xUJQ).

Figure 1

Left tympanic membrane. Left-normal TM. Right-same TM after modified Valsalva with vascular engorgement sparing the pars tensa. TM indicates tympanic membrane.

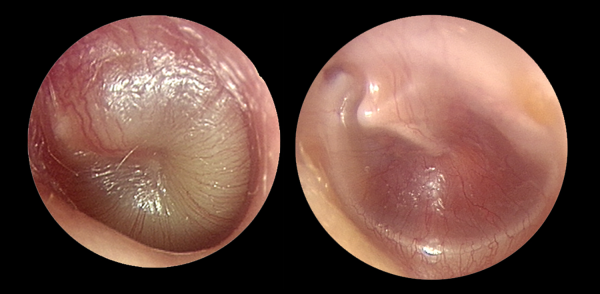

Concerns about the overdiagnosis and overtreatment of suspected AOM have led to specific changes in society guidelines. The American Academy of Pediatrics requires the presence of a bulging of the tympanic membrane (TM; Figure 2) in its clinical practice guideline specifically to address overtreatment of red eardrums and otitis media with effusion.

Figure 2

Left, bulging acute otitis media. Right, retracted drum in otitis media with effusion. Both show vascular engorgement involving the pars tensa.

The AAO-HNS guideline on tympanostomy tubes in children recommends deferring tube placement in children who present with normal ears at initial consultation —even when there is a documented history of recurrent AOM. Studies show incomplete adherence to these guidelines. - When a child presents with a history of 10 episodes of AOM, has multiple drug allergies, and gastrointestinal symptoms complicating antibiotic use, tympanostomy tubes are often recommended even when middle ear effusion is absent. Noncompliance with guidelines in such a setting is not always wrong. The modest reduction in incidence of AOM with tympanostomy tubes - is enhanced by their other positive effects—decreased severity of AOM symptoms, improved diagnosis of AOM (no drainage, no infection), and sparing of systemic antibiotics thanks to effective ototopical treatments. Quality-of-life improvement , must be weighed against the known risks of surgery and general anesthesia.

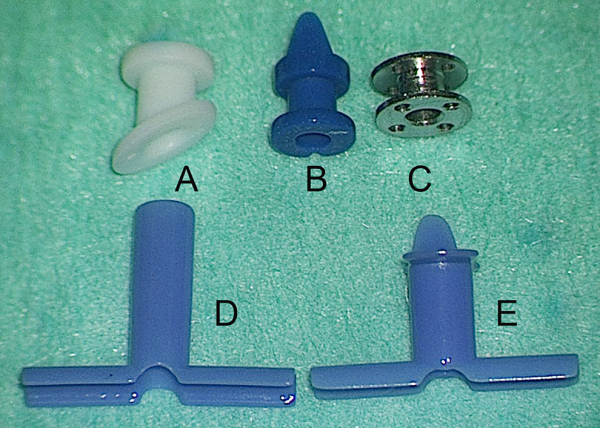

The Best Tympanostomy Tube/The Best Way to Place It

There are 3 materials (fluoroplastic, silicone elastomer, or metal) and 2 basic designs (short-term, longer-term) used in the majority of tympanostomy tubes. , Armstrong II, Paparella I, Donaldson, Shepard, Sheehy, and Reuter bobbins are the dominant short-term tympanostomy tubes in the world. They share a grommet design with 2 flanges of varying size separated by a short shaft. The different designs and materials have slightly different rates of occlusion (clogging), infection, duration of function, and rates of persistent perforation after extrusion. - None is clearly superior (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Tympanostomy tubes—first row short-term grommets; second row long-term tubes. A-Armstrong beveled grommet; B-Paparella I grommet; C-Reuter bobbin; D-Goode T-tube; E-butterfly tube.

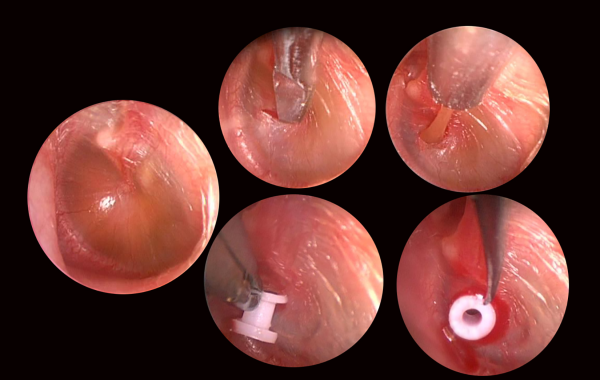

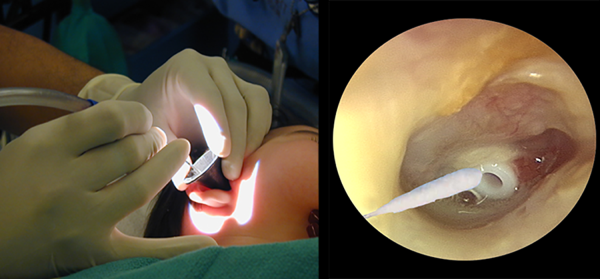

Short-term tubes are usually placed under general anesthesia in young children. They are typically placed through a radial incision in the pars tensa, either anteriorly or posteroinferiorly (to avoid damaging the stapes and incus long process; Figure 4). While different surgeons employ minor technical variations in tube insertion, use of a pick for final tube positioning is associated with low-rates of accidental middle ear insertion. If (when) a tube is partially or completely inserted into the middle ear, do not attempt to remove it with alligator forceps, rather reach past it with a right-angle hook and tease it back into correct position (Figure 5).

Figure 4

Placing a grommet type tube.

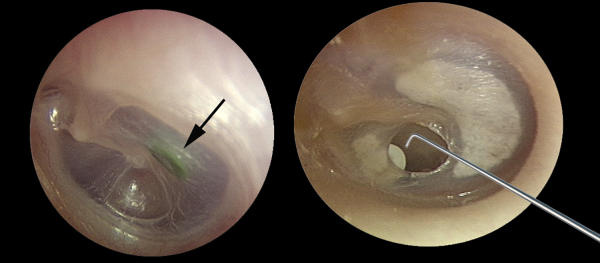

Figure 5

Left, green tube lost in middle ear (arrow); right, recovery of displaced tube with right angle hook.

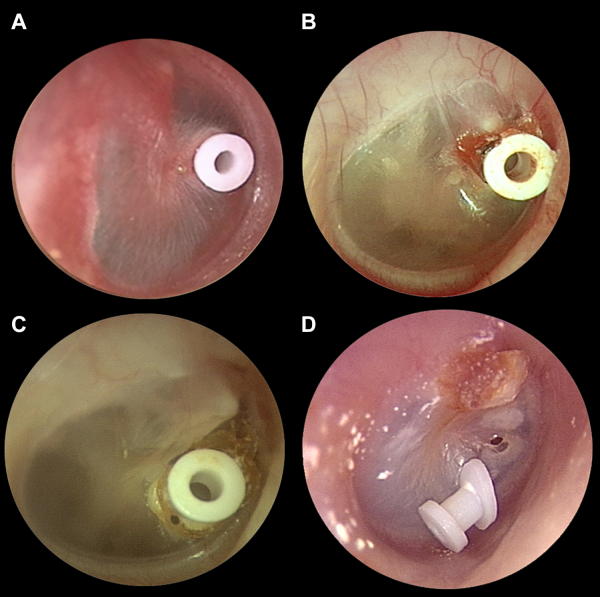

Grommet tubes typically extrude about a year after placement. Migrating squamous epithelium accumulates under the outer flange of the tube and eventually forces the inner flange through the TM and into the ear canal (Figure 6).

Figure 6

A, Newly placed tube flush to TM; (B) aging tube, lifted by squamous debris; (C) extruding tube with inner flange coming through drum; (D) recently extruded tube with TM perforation closing behind it. TM indicates tympanic membrane.

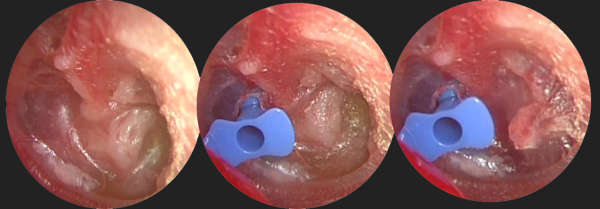

Long-term tympanostomy tubes resist forces of extrusion with a larger inner flange (Per-Lee, Paparella II), no outer flange (Armstrong I), or both (Goode T-tube). These long-term tubes have higher rates of granulation tissue formation and of nonhealing perforation , than short-term designs. Long-term tubes are often chosen when short-term tubes have extruded prematurely, or when there is atelectasis or significant retraction of the drum and long-term intubation is desired (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Left, atelectatic drum with middle ear effusion and retraction into the sinus tympani; middle, placement of long-term butterfly tube; right, mechanical reduction of the deep retraction pocket after tube placement.

Tympanostomy Tube Otorrhea

Approaches to the management of tympanostomy tube otorrhea are addressed in detail elsewhere in this issue. Most episodes of acute tympanostomy tube otorrhea can be treated with ototopical drops. There appears to be an advantage to steroid containing drops, especially when granulation tissue surrounds the draining tube (Figure 8).

Figure 8

Left, acute tube otorrhea; right, tube otorrhea with granulation.

If otorrhea persists after initial treatment, aural toilette (cleansing of the ear canal with suction) under the operating microscope and culture of the discharge at the tube orifice can help guide subsequent therapy with systemic or topical agents (Figure 9).

Figure 9

Left, aural toilette; right, culturing the tube orifice with a urethral swab.

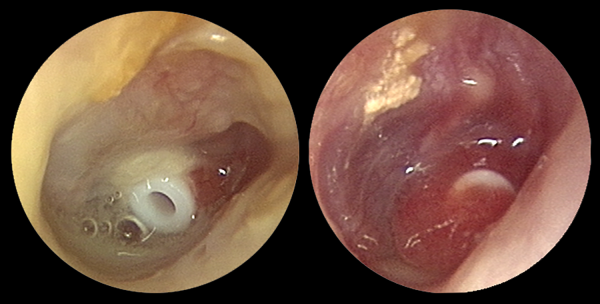

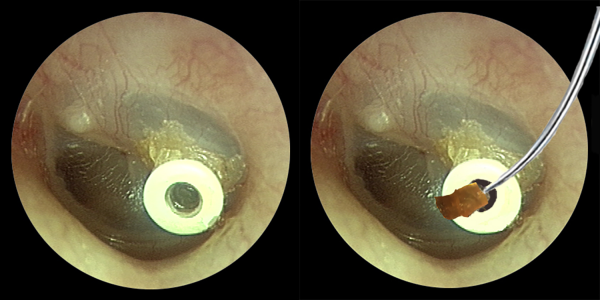

Tube Clogging

When the lumen of a tympanostomy tube becomes clogged, it renders the tube temporarily ineffective. Clogging can occur immediately after tube placement (especial in ears with effusion at surgery), later following an episode of otorrhea, or as part of the normal extrusion process. Some clogs can be dissolved with ototopical drops or peroxide solutions. Clogs in recently placed tubes (<6-9 months) can be extracted or medial displaced into the middle ear under the operating microscope. Restraint is advisable during this maneuver, completed with a curved pick. Clogs in extruding tubes are not amenable to mechanical removal (Figure 10).

Figure 10

Left, a clogged tube; right the clog can be displaced into the middle ear or, as here, removed like a champagne cork.

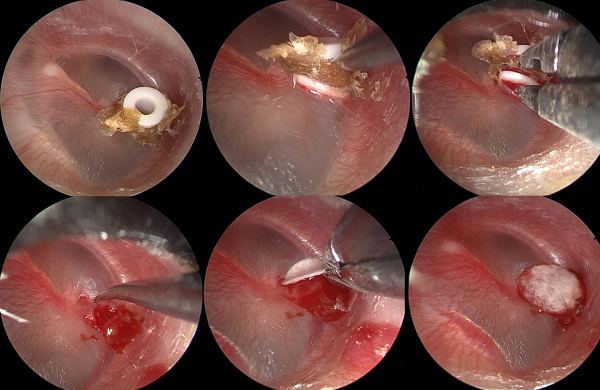

Tube Removal

The optimal timing and methods for removal of retained tympanostomy tubes is addressed separately. Patch materials including paper, gelatin film, and porcine acellular submucosa (collagen matrix) are often used after tube removal and freshening of the resultant perforation (Figure 11).

Figure 11

Top left to bottom right—retained tube with squamous debris is elevated with a pick and removed with cup forceps. The resultant perforation is rimmed with a pick and a collagen matrix patch is applied.

Conclusion

Tympanostomy tube placement is the most common surgery performed in children requiring general anesthesia. While some elements of tympanostomy tube care have been addressed in clinical studies, much of clinical practice is guided by shared experience. This article illustrates some of the techniques that have proved effective during years of pediatric otolaryngology practice.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Glenn Isaacson

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5977-1796

References

- 1. Isaacson G. Otoscopic diagnosis of otitis media [published online May 19, 2016]. Minerva Pediatr. 2016;68(6):470–477. Review.

- 2. Rothman R, Owens T, Simel DL. Does this child have acute otitis media? JAMA. 2003;290(12):1633–1640. Review.

- 3. Lieberthal AS, Carroll AE, Chonmaitree T, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media [published online February 25, 2013]. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3):e964–e999. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-3488.

- 4. Rosenfeld RM, Schwartz SR, Pynnonen MA, et al. Clinical practice guideline: Tympanostomy tubes in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;149(1 suppl):S1–35. doi:10.1177/0194599813487302.

- 5. Cullas Ilarslan NE, Gunay F, Topcu S, Ciftci E. Evaluation of clinical approaches and physician adherence to guidelines for otitis media with effusion [published online June 26, 2018]. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;112:97–103. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.06.040.

- 6. Forrest CB, Fiks AG, Bailey LC, et al. Improving adherence to otitis media guidelines with clinical decision support and physician feedback [published online March 11, 2013]. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):e1071–e1081. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-1988.

- 7. Sajisevi M, Schulz K, Cyr DD, Wojdyla D, Rosenfeld RM, Tucci D, Witsell DL. Nonadherence to guideline recommendations for tympanostomy tube insertion in children based on mega-database claims analysis [published online October 3, 2016]. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(1):87–95. doi:10.1177/0194599816669499.

- 8. Gisselsson-Solen M, Reference group for the National Quality Register for Tympanic Membrane Ventilation Tubes. The Swedish grommet register—hearing results and adherence to guidelines. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;110:105–109. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.05.010.

- 9. Casselbrant ML, Kaleida PH, Rockette HE, et al. Efficacy of antimicrobial prophylaxis and of tympanostomy tube insertion for prevention of recurrent acute otitis media: results of a randomized clinical trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11(4):278–286.

- 10. Lous J, Ryborg CT, Thomsen JL. A systematic review of the effect of tympanostomy tubes in children with recurrent acute otitis media [published online June 2, 2011]. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;75(9):1058–1061. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.05.009. Review.

- 11. Mc Donald S, Langton Hewer CD, Nunez DA. Grommets (ventilation tubes) for recurrent acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD004741. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004741.pub2. Review. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Apr 06;4:CD004741.

- 12. Rosenfeld RM, Bhaya MH, Bower CM, et al. Impact of tympanostomy tubes on child quality of life. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126(5):585–592.

- 13. Lameiras AR, Silva D, O Neill A, Escada P. Quality of life of children with otitis media and impact of insertion of transtympanic ventilation tubes in a Portuguese population. Acta Med Port. 2018;31(1):30–37. doi:10.20344/amp.9457.

- 14. O’Niel MB, Cassidy LD, Link TR, Kerschner JE. Tracking tympanostomy tube outcomes in pediatric patients with otitis media using an electronic database. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;79(8):1275–1278. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.05.029.

- 15. Tavin ME, Gordon M, Ruben RJ. Hearing results with the use of different tympanostomy tubes: a prospective study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1988;15(1):39–50.

- 16. Isaacson G, Rosenfeld RM. Care of the child with tympanostomy tubes. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1996;43(6):1183–1193. Review.

- 17. Knutsson J, Priwin C, Hessén-Söderman AC, Rosenblad A, von Unge M. A randomized study of four different types of tympanostomy ventilation tubes—full-term follow-up. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;107:140–144. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.02.012.

- 18. Kim D, Choi SW, Lee HM, Kong SK, Lee IW, Oh SJ. Comparison of extrusion and patency of silicon versus thermoplastic elastomer tympanostomy tubes. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2019;46(3):311–318. doi:10.1016/j.anl.2018.09.002.

- 19. Lindstrom DR, Reuben B, Jacobson K, Flanary VA, Kerschner JE. Long-term results of Armstrong beveled grommet tympanostomy tubes in children. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(3):490–494.

- 20. Isaacson G. Six Sigma tympanostomy tube insertion: achieving the highest safety levels during residency training. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139(3):353–357. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2008.06.012.

- 21. Kay DJ, Nelson M, Rosenfeld RM. Meta-analysis of tympanostomy tube sequelae. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;124(4):374–380.

- 22. Matt BH, Miller RP, Meyers RM, Campbell JM, Cotton RT. Incidence of perforation with Goode T-tube. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1991;21(1):1–6.

- 23. Chan KH, Allen GC, Kelley PE, et al. Dornase alfa ototoxic effects in animals and efficacy in the treatment of clogged tympanostomy tubes in children: a preclinical study and a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144(9):776–780. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2018.1101.

- 24. Brenman AK, Milner RM, Weller CR. Use of hydrogen peroxide to clear blocked ventilation tubes. Am J Otol. 1986;7(1):47–50.

- 25. Pribitkin EA, Handler SD, Tom LW, Potsic WP, Wetmore RF. Ventilation tube removal. Indications for paper patch myringoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118(5):495–497.

- 26. Schraff SA, Markham J, Welch C, Darrow DH, Derkay CS. Outcomes in children with perforated tympanic membranes after tympanostomy tube placement: results using a pilot treatment algorithm. Am J Otolaryngol. 2006;27(4):238–243.

- 27. Wang N, Isaacson G. Collagen matrix as a replacement for Gelfilm® for post-tympanostomy tube myringoplasty. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.110136.