Introduction

Chronic supraglottic edema is a rare condition, especially in the pediatric population. It can present with symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing, dyspnea, stridor, and difficulty swallowing. There is a wide differential diagnosis, including infectious, autoimmune, allergic, vasculitic, and neoplastic processes. Histopathology can help narrow the diagnosis as there is a more limited differential diagnosis for granulomatous inflammation versus nongranulomatous inflammation. We discuss the case of a pediatric patient who presented with chronic sleep-disordered breathing and was found to have severe, granulomatous inflammation of the supraglottic larynx.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 12-year-old male presented to the pediatric otolaryngology clinic for sleep-disordered breathing as well as daytime breathing symptoms. He had undergone tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy 2 years prior to presentation for adenotonsillar hypertrophy and sleep-disordered breathing symptoms, which did improve to some extent after surgery. However, his parents described worsening snoring, labored breathing, dyspnea with exertion, witnessed apneas, and enuresis over the past 6 months. This prompted a sleep study which revealed severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), with overall apnea–hypopnea index of 46.9 events/hour, 64.3 events/hour during REM sleep, and an oxygen nadir or 67%. Flexible laryngoscopy by the referring otolaryngologist had been notable for inflamed lingual tonsils and moderate supraglottic edema. He was then referred to pediatric otolaryngology at the American Family Children’s Hospital (AFCH) at the University of Wisconsin for further evaluation and management. Endoscopy at AFCH demonstrated a markedly abnormal larynx with severely enlarged supraglottic structures—without signs of acute erythema or ulceration—as well as elements of moderate lingual tonsil hypertrophy.

Due to concern for a tenuous airway, the patient was admitted to the hospital with plans for laboratory and radiographic workup, as well as to secure the airway and obtain tissue biopsies. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of the head and neck revealed diffuse circumferential thickening and enhancing edema involving the entirety of the supraglottic larynx with effacement of the supraglottic airway, but no focal mass lesion. Chest X-ray was normal. Extensive laboratory evaluation was unrevealing; this included normal laboratory values for sarcoidosis (ACE, Ca, lysozyme), chronic granulomatous disease (NADPH oxidase), hereditary angioedema (complement C4), ANCA-vasculitis (c-ANCA, anti-MPO, anti-PR3), antigen evaluation for blastomycosis and histoplasmosis, general inflammatory conditions (CBC, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, antinuclear antibody), and immunodeficiency (immunoglobulin G, immunoglobulin M, immunoglobulin A).

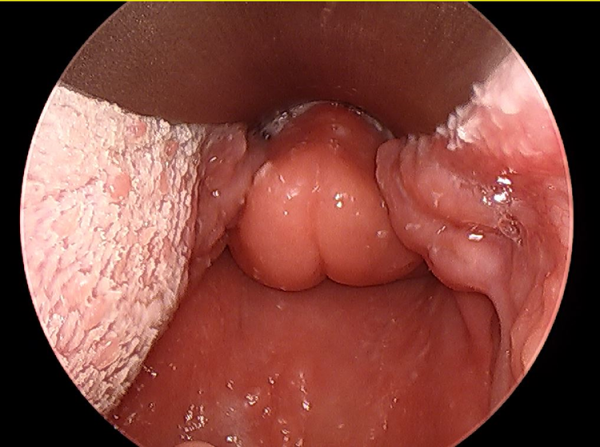

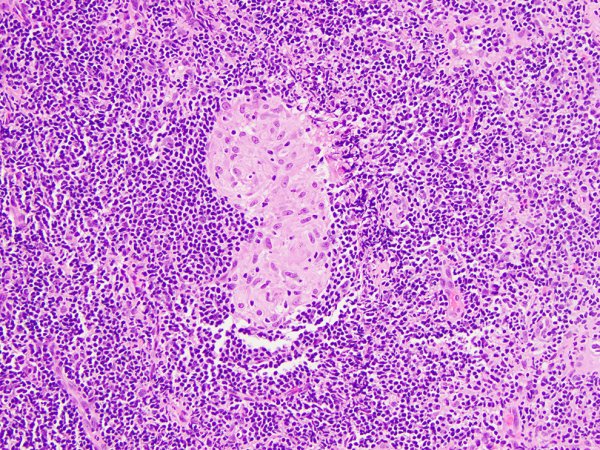

Awake tracheostomy was performed with the patient on CPAP, followed by direct microlaryngoscopy (DML), bronchoscopy, and supraglottic biopsies (Figure 1). Tissue biopsies were notable for lymphocytic-predominant chronic inflammation with loosely formed non-necrotizing granulomas (Figure 2). Fungal cultures and acid-fast bacilli staining were negative. Immunohistochemistry for synaptophysin and pancytokeratin was negative. Immunohistochemistry for CD3 and CD20 showed a mixed population of lymphocytes, helping to exclude a neoplastic process. Epiglottic cartilage was normal without signs of perichondritis.

Figure 1

Initial, pretreatment, direct microlaryngoscopy view demonstrating diffuse, firm edema of epiglottis and other supraglottic structures.

Figure 2

Arytenoid submucosal tissue containing a non-necrotizing granuloma (cluster of epithelioid cells with pink cytoplasm) within a background of small lymphocytes.

Due to a family history of Crohn disease and non-necrotizing granulomas noted on pathology, pediatric gastroenterology was consulted. Fecal calprotectin was elevated, but magnetic resonance enterography was normal. He then underwent upper and lower gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopies with biopsies. These studies were notable for edema and erosions in the proximal descending colon, petechiae and nodularity in the terminal ileum, congested duodenal mucosa with scattered erosions, and mild chronic inactive gastritis of the gastric mucosa. Biopsies of these locations, however, were within normal limits.

During his initial hospitalization, he underwent steroid injections of the edematous supraglottic laryngeal structures. He was discharged from the hospital with a tracheostomy in place. Since inflammatory bowel disease remained the leading entity on the differential diagnosis, initiation of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapies was discussed as the next reasonable step if edema did not improve with local or systemic steroid therapies. He returned to the operating room 2 weeks after discharge for DML and steroid injections with mild improvement noted in laryngeal swelling in comparison to previous examinations. Given this improvement, the involved teams decided to continue with laryngeal steroid injections. He underwent serial scope examinations and steroid injections every 1 to 2 months with gradual improvement in each examination. After 3 sets of injections, he underwent repeat steroid injection in addition to right partial arytenoidectomy and lingual tonsillectomy. Three months later, he underwent steroid injection and left supraglottoplasty with excision of supra-arytenoid tissue and “pepper pot” CO2 laser resurfacing treatment of the posterior lateral epiglottis and aryepiglottic fold. After these procedures, the airway appeared much more patent, and the patient was able to tolerate tracheostomy capping. One month later, he was admitted for overnight sleep study with his tracheostomy capped, which he tolerated well. He then underwent DML and drug-induced sleep endoscopy which was notable for persistent epiglottic edema but with a patent airway noted on inspiration and expiration. He was decannulated postoperatively and discharged home. At 3 months post-decannulation, the patient continues to do well without sleep-disordered breathing or noisy daytime breathing.

Discussion

We describe a pediatric patient who presented with severe OSA due to chronic supraglottic swelling. This is an uncommon presentation, and therefore a wide differential must be considered. The differential diagnosis for supraglottic edema is very broad and includes infectious, autoimmune, allergic, vasculitic, and neoplastic processes. Acute infectious causes include acute bacterial epiglottitis and laryngotracheobronchitis that can be due to a variety of bacterial, fungal, and viral organisms. Although important to recognize, these usually present with rapidly progressive edema of the supraglottis leading to airway obstruction as well as pain and fevers, which is not consistent with the more chronic course of our patient. Chronic infectious causes include mycobacterium and fungal organisms such as histoplasmosis and blastomycosis. Amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, relapsing polychondritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, chronic granulomatous disease, and common variable immunodeficiency are other noninfectious disorders which have been known to cause chronic supraglottitis. Hereditary angioedema, which can manifest in recurrent upper airway swelling, should not be missed. Neoplasm, including rhabdomyosarcoma, granular cell tumor, and infiltrative lymphoproliferative disorders are also important to consider. Initial workup should include imaging to better characterize extent of swelling and identify possible mass lesions. Laboratory studies for the abovementioned causes should be initiated early.

Analysis of histopathology aids in narrowing the differential. In this case, supraglottic biopsies revealed lymphocytic-predominant chronic inflammation with loosely formed, non-necrotizing granulomas. The presence of granulomatous inflammation in conjunction with the overall clinical picture rules out several of the previously considered etiologies including hereditary angioedema, relapsing polychondritis, and common variable immunodeficiency, which do not typically present with granulomas. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis has been reported to cause supraglottitis but was ruled out in this case due to negative autoimmune workup and absence of necrosis or vasculitis on histology. Mycotic infections such as histoplasmosis and blastomycosis can present with granulomatous inflammation without pulmonary disease, but fungal cultures, as well as urine and serum antigen studies were negative. Similarly, there was no evidence of acid-fast bacilli on microscopy or mycobacterium on extended culture. Sarcoidosis remained high on the differential diagnosis, as it presents with non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation and has been known to present with isolated laryngeal involvement., Laboratory findings typically suggestive of sarcoidosis such as hyperglobulinemia, hypercalcemia, and hypercalciuria were not present nor was an elevated angiotensin converting enzyme, although this is a poorly sensitive test. Crohn disease is another cause of granulomatous inflammation that, while rare, can present with laryngeal manifestations.- Due to this patient’s family history of inflammatory bowel disease and lack of other identifiable etiology, this was presumed to be the most likely diagnosis. Fecal calprotectin, a nonspecific marker of bowel inflammation, was notably positive and there were some gross signs of erosion identified on upper and lower GI endoscopy, but definitive histologic signs of inflammatory bowel disease were not found.

Inflammatory bowel disease has 2 main phenotypes, Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis, both of which result in chronic relapsing inflammation of the GI tract. Crohn disease can affect any part of the GI tract, from mouth to anus, and most patients present with signs and symptoms of bowel inflammation, such as diarrhea, abdominal cramping, anemia, and perianal disease. Histologically, Crohn classically appears as noncontiguous lesions with transmural ulceration of the bowel wall and noncaseating granulomas. Inflammatory infiltrates of neutrophils, plasma cells, and lymphocytes with large lymphoid aggregates are typically present, along with crypt abscesses and cryptitis.

Although intestinal involvement is certainly the most common, inflammatory bowel disease can present with extraintestinal manifestations, including those of the head and neck.- Head and neck manifestations are present in up to 13% of patients with Crohn disease, and oral involvement may be the presenting symptom in up to 60% of patients. Oral aphthous ulcers are the most common oral lesion seen, but angular cheilitis/stomatitis, edema, and ulceration of the oral mucosa can occur. Laryngeal manifestations of Crohn disease are very rare, with only 13 currently reported in the literature,, and only 2 reported in pediatric patients., All but 2 of these patients presented with supraglottic granulomatous inflammation in the setting of previously diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease. One patient presented with difficulty breathing and was found to have chronic granulomatous inflammation of the epiglottis and aryepiglottic folds. Six months later, she developed diarrhea, abdominal pain, and perianal fistulizing disease, with subsequent histologic examination of the GI tract revealing Crohn disease. Another patient presented with symptoms of upper airway obstruction due to granulomatous supraglottic inflammation and was then found to have histologic evidence of Crohn disease in the terminal ileum, despite relatively normal gross appearance on GI endoscopy and lack of GI symptoms. Ahmed et al reports a case of a pediatric patient who presented with granulomatous inflammation of the trachea requiring urgent tracheostomy, without GI symptoms, who was subsequently given a diagnosis of Crohn after colonoscopy.

Laryngeal manifestations of Crohn disease seem to respond to treatment of the GI disease, though particular attention should be given to stabilization of the airway. In the reported cases, local and systemic corticosteroids were the mainstay of treatment for reducing airway inflammation. Patients who did not respond adequately to steroids were typically advanced to steroid-sparing systemic therapies commonly used in IBD, including nonbiologic medications (azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, mesalamine) and anti-tumor necrosis factor therapies (infliximab, adalimumab) with good success. Surgical management can also be necessary to stabilize the airway, with one patient, in addition to the one described in this report, requiring tracheostomy and one undergoing supraglottoplasty. Although not previously reported for cases of laryngeal Crohn disease, CO2 laser resurfacing (“pepper pot”) techniques have been used to reduce airway redundancy and achieve decannulation in cases of laryngeal sarcoidosis as well as idiopathic, nongranulomatous chronic supraglottitis.,

In conclusion, we report a case of a pediatric patient who presented with severe supraglottic edema with evidence of non-necrotizing granulomas. Overall workup was unremarkable, leaving isolated laryngeal sarcoidosis or inflammatory bowel disease as the leading diagnoses. Although no evidence of bowel involvement has been found to date, his family history of IBD and the knowledge that laryngeal involvement has been demonstrated to precede symptomatic GI manifestations in Crohn disease necessitates continued careful surveillance. It may be that routine sampling of his GI tract simply missed developing inflammatory changes. In summary, in cases of chronic supraglottic swelling of unknown etiology, the key management principles include maintaining a broad differential, obtaining a detailed family history of autoimmune disease, and stabilizing the airway using local and systemic therapies, as well as surgical interventions as necessary.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Sophia M. Colevas

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3242-1590

Supplemental Material Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Aono Y, Imokawa S, Uto T, Sato J, Tanioka F, Suda T. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis involving the epiglottis. Respirol Case Rep. 2017;5(3):e00226. doi:10.1002/rcr2.226

- 2. Haar JG, Chaudhry AP, Kaplan HM, Milley PS. Granulomatous laryngitis of unknown etiology. Laryngoscope. 1980;90(7 pt 1):1225–1229. doi:10.1288/00005537-198007000-00018

- 3. Dean CM, Sataloff RT, Hawkshaw MJ, Pribikin E. Laryngeal sarcoidosis. J Voice. 2002;16(2):283–288. doi:10.1016/s0892-1997(02)00099 -1

- 4. Ungprasert P, Carmona EM, Crowson CS, Matteson EL. Diagnostic utility of angiotensin-converting enzyme in sarcoidosis: a population-based study. Lung. 2016;194(1):91–95. doi:10.1007/s00408-015-9826-3

- 5. Croft CB, Wilkinson AR. Ulceration of the mouth, pharynx, and larynx in Crohn disease of the intestine. Br J Surg. 1972;59(4):249–252.

- 6. Loos E, Lemkens P, Poorten VV, Humblet E, Laureyns G. Laryngeal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. J Voice. 2019;33(1):1–6. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2017.09.021

- 7. Price SE, Frampton SJ, Coelho T, et al. Crohn supraglottitis—the presenting feature of otherwise asymptomatic disease. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol Extra. 2013;8(4):131–136. doi:10.1016/j.pedex.2013.08.004

- 8. Yang J, Maronian N, Reyes V, Waugh P, Brentnall T, Hillel A. Laryngeal and other otolaryngologic manifestations of Crohn disease. J Voice. 2002;16(2):278–282. doi:10.1016/s0892-1997(02)00098-x

- 9. Wilder WM, Slagle GW, Hand AM, Watkins WJ. Crohn disease of the epiglottis, aryepiglottic folds, anus, and rectum. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1980;2(1):87–91. doi:10.1097/00004836-198003000-00013

- 10. Pervez T, Lee CH, Seton C, Raftopulos M, Birman C, O’loughlin E. Obstructive sleep apnoea in a paediatric patient with laryngeal Crohn disease. J Paediatr Child Health. 2018;54(2):197–199. doi:10.1111/jpc.13753

- 11. Ramsdell WM, Shulman RJ, Lifschitz CH. Unusual appearance of Crohn disease. Am J Dis Child. 1984;138(5):500–501.

- 12. Dupuy A, Cosnes J, Revuz J, et al. Oral Crohn disease. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:439–442.

- 13. Plauth M, Jenss H, Meyle J. Oral manifestations of Crohn disease: an analysis of 79 cases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1991;13(1):29–37.

- 14. Ahmed KA, Thompson JW, Joyner RE, Stocks RM. Airway obstruction secondary to tracheobronchial involvement of asymptomatic undiagnosed Crohn disease in a pediatric patient. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69(7):1003–1005. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.02.004

- 15. Kelly JH, Montgomery WW, Goodman ML, Mulvaney TJ. Upper airway obstruction associated with regional enteritis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1979;88(1 pt 1):95–99. doi:10.1177/000348947908800116

- 16. Butler CR, Nouraei SA, Mace AD, Khalil S, Sandhu SK, Sandhu GS. Endoscopic airway management of laryngeal sarcoidosis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136(3):251–255. doi:10.1001/archoto.2010.16

- 17. Smith MM, Nokso-Koivisto J, Leader BA, Wilcox LJ, Rutter MJ. CO2 laser supraglottic resurfacing for non-granulomatous chronic supraglottitis in two children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;120:162–165. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.02.031

- 18. Hoffman MR, Mai JP, Dailey SH. Idiopathic supraglottic stenosis refractory to multiple interventions improved with serial office-based steroid injections. J Voice. 2018;32(6):767–769. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2017.09.016