Introduction

Nasal bone fracture is a common presentation to the Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) Surgeon, accounting for 39% of all facial bone fractures, particularly due to its prominence on the face. The most common mechanisms of injury include assault, sporting injuries, falls, and motor vehicle accidents. Although complications such as epistaxis or septal hematoma may occur and need to be managed acutely, longer term sequelae include nasal deformity and nasal obstruction. Simple, closed, nasal fractures can be manipulated under anesthesia (MUA #nasal bones), primarily to improve the aesthetic outcome, but may also have an impact on nasal obstruction. Assessment for this procedure usually first takes place in an emergency ENT Clinic after approximately 5 days have passed from the time of injury, to allow for facial swelling to sufficiently subside, and to make a fair evaluation of shape. Although there is no official consensus, it is accepted in the United Kingdom that performing this procedure within 2 to 3 weeks after the injury provides the optimal cosmetic outcome, as beyond this window the nasal bones begin to fuse, and a formal operation such as septorhinoplasty, may be necessary to achieve the desired result. Furthermore, UK departments widely perform this procedure under general anaesthetic (GA).

The COVID-19 global pandemic was unprecedented in how all health services had to rapidly adapt to balance both clinical demand and safety of its staff and patients by limiting face-to-face interaction and increasing virtual consultations. Staff in the ENT department are particularly at risk due to the close proximity required to examine patients and high volume of aerosol-generating procedures (AGP) performed. In our hospital, all nononcological operating ceased during the pandemic.

Before the pandemic, our department, like many other UK ENT departments, performed MUA #nasal bones in theater under GA; however, at the height of the pandemic in March 2020, there was a shift to perform procedures under local anaesthetic (LA) in the outpatient clinic, in order to overcome the unavailability of elective operating theaters, while still providing a safe nasal fracture service to patients.

We evaluate how the transition of our MUA #nasal bones service from GA to LA affected patient outcomes and whether LA could provide a safe and effective alternative to performing these procedures in the future, in the event of further COVID-19 surges and reduced theater capacity.

Patients and Methods

We retrospectively analyzed all recorded referrals of nasal injury made to the Emergency ENT Clinic at Northwick Park Hospital, London, between January and August 2020 and evaluated the notes of patients subsequently seen in the outpatient clinic. Patient demographics were recorded, along with timings to clinic appointment and any subsequent procedure. Exclusion criteria were anyone who suffered an open injury or required elevation of depressed nasal bones. The procedure was performed using a standardized technique to restore the deformed nasal bones to the midline. Procedures under LA were performed with an external nasal nerve block (1 mL of 2% lidocaine) and topical anesthetic/decongestion (2.5 mL of lidocaine hydrochloride 5% wt/vol and phenylephrine hydrochloride 0.5% wt/vol). Procedures were performed in a separate room designed for AGP, using enhanced personal protective equipment (PPE) for the surgeon and clinic nurse. Local decontamination protocols were in place to cleanse the room between patients.

Patients who underwent MUA #nasal bones participated in a postoperative telephone interview at one month after their procedure, consisting of questions to subjectively evaluate satisfaction of (1) the shape of their nose and (2) nasal airflow. This was quantified using a 5-point numerical Likert scale, with 1 being very dissatisfied and 5 being very satisfied. We also recorded whether patients would be happy to undergo the same procedure again in hindsight, and if they felt they required any further surgical correction to their nose. Finally, we asked if they were happy overall with the shape of their nose and with their breathing.

Statistical analysis of the difference between pre- and postoperative scores for each patient was carried out using the paired t test for significance. Comparison of LA with GA was made using the independent t test for significance. Mean values are presented with the standard error. Data were recorded in Microsoft Excel and statistical tests were performed using SPSS software.

Results

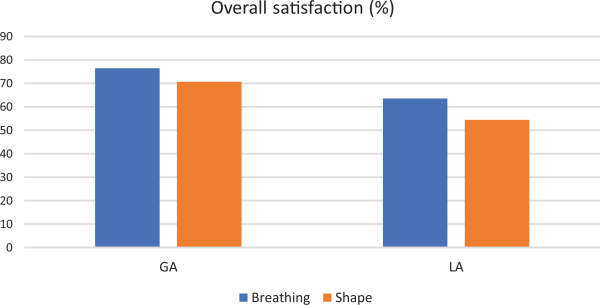

Key results are presented in Table 1. There were 205 referrals to the Emergency ENT Clinic for “nasal injury” during the study period. The most common mechanisms of injury were Accidents/Falls (44%, n = 91), Assault (26%, n = 53), and Sport (13%, n = 27). The majority of patients were male (70%, n = 143) and the average age was 35.4 years (range: 1-92 years).

One-hundred and sixty-eight patients attended their appointment and there were 48 MUA #nasal bones performed in total (n = 21 under GA, n = 27 under LA). From mid-March to the end of the study period, there were no procedures performed under GA, apart from one performed privately and thus excluded from the paper.

Manipulation Under Anesthesia #Nasal Bones GA

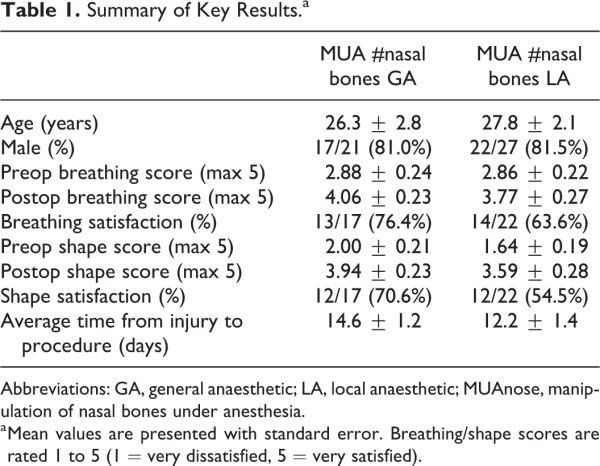

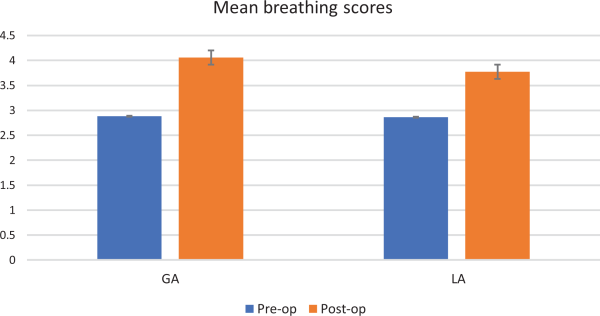

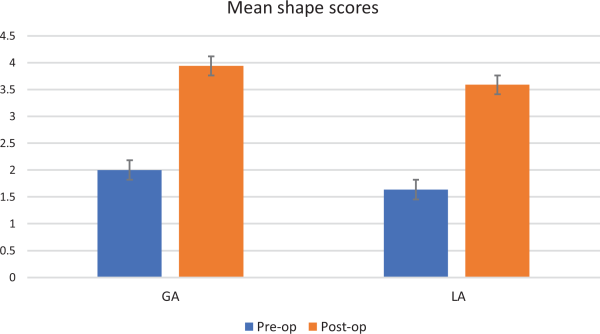

In total, there were 21 procedures under GA. The mean age was 26.3 ± 2.8 years (range: 12-60). Seventeen of 21 patients were successfully contacted for follow-up interview. Breathing satisfaction scores in these patients preoperatively were 2.88 ± 0.24 and significantly increased after MUA #nasal bones GA to 4.06 ± 0.23 (P < 0.05; Figure 1). Aesthetic scores also significantly improved from preprocedure (2.00 ± 0.21 to 3.94 ± 0.23, P < 0.05; Figure 2). When asked if now satisfied with their breathing, 13 (76.4%) of 17 replied “yes,” and 12 (70.6%) of 17 were satisfied with the shape (Figure 3). Sixteen (94.1%) of 17 patients would have this procedure again in hindsight, though 7 (41.2%) of 17 would consider further corrective surgery. Of these patients, 4 of 7 felt their breathing was not completely normal compared to before the injury, and the remaining patients had issues with the shape (these patients were all noted to have lower cartilaginous deformities in their clinic letters).

Figure 1

Mean breathing scores. Mean breathing scores on Likert scale 1 to 5 (1 = very dissatisfied, 5 = very satisfied). Blue = preoperative score, orange = postoperative score. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Figure 2

Mean shape scores. Mean shape scores on Likert scale 1 to 5 (1 = very dissatisfied, 5 = very satisfied). Blue = preoperative score, orange = postoperative score. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Figure 3

Satisfaction scores. Overall percentage of patients satisfied postoperatively with their breathing (blue) and shape (orange).

Manipulation Under Anesthesia #Nasal Bones LA

In total, there were 27 procedures under LA. The mean age was 27.8 ± 2.1 years (range: 13-64). Twenty-two of 27 patients were successfully contacted for follow-up interview. Breathing satisfaction scores in these patients preoperatively were 2.86 ± 0.22 and significantly increased after MUA #nasal bones LA to 3.77 ± 0.27 (P < 0.05; Figure 1). Aesthetic scores also significantly improved from preprocedure (1.64 ± 0.19 to 3.59 ± 0.28, P < 0.05; Figure 2). When asked if now satisfied with their breathing, 14 (63.6%) of 22 replied “yes,” and 12 (54.5%) of 22 were satisfied with the shape (Figure 3). Twenty-one (95.5%) of 22 patients would have this procedure again in hindsight, though 13 (59.1%) of 22 would consider further corrective surgery. Of these patients, 6 of 13 had issues with their breathing, 2 of 13 had significant residual deformity but were told before the procedure that they would have a low chance of success as they presented >30 days, and the remaining patients felt they had minor issues with the shape and would want to consider septorhinoplasty in the future.

Manipulation Under Anesthesia #Nasal Bones GA Versus LA

There were no statistically significant differences between GA and LA, respectively, for postoperative breathing score (4.06 ± 0.23 vs 3.77 ± 0.27, P = 0.45) or shape score (3.94 ± 0.23 vs 3.59 ± 0.28, P = 0.23).

Average Time Frames

For all patients who were referred, the average time from injury to referral was 2.91 ± 0.61 days and from referral to clinic appointment was 8.19 ± 0.28 days. The average number of days from injury to procedure in the GA group was 14.6 ± 1.2 days and in the LA group was 12.2 ± 1.4 days.

Discussion

Patients in our study were predominantly young and male, which is in keeping with findings from previous studies.- Accidental injury, including falls and assaults were the most common mechanism, also consistent with other published work. Demographics between GA and LA groups were well matched, reducing the number of confounding variables.

The method of anesthesia used for MUA #nasal bones in the United Kingdom varies widely, where only a small number of consultants have reported use of LA (26.8%). The technique to achieve LA varies across centers and requires a greater level of expertise from the surgeon, in comparison to techniques using GA. The fact there is poor utilization of LA despite previous studies showing equivocal outcomes between techniques, and the increasing need to reduce theater burden during the COVID-19 pandemic, highlights the need for our work to further demonstrate the utility of LA.

The decision to utilize LA as a technique was necessitated by the rapid reduction in elective theater capacity. Our trust had an average of 19 elective ENT theater sessions per week across hospital sites before the pandemic, but from March 2020, this reduced to zero. Only head and neck cancer operations were taking place, at alternative “COVID-19-free” hospitals outside the trust with an average of 2 sessions per week. With no theaters to perform MUA #nasal bones under GA, the option was to perform procedures under LA with appropriate safety measures in place, or to cease the nasal fracture service entirely, which would have had a detrimental outcome for patients. Fortunately, a protracted Emergency ENT Clinic service was running throughout the pandemic, which facilitated this.

Manipulation Under Anesthesia #Nasal Bones GA Versus LA Outcomes

In our study, there was a clinically and statistically significant improvement in both breathing and aesthetic scores after MUA #nasal bones, regardless of the anesthetic technique used. There was a trend toward GA providing slightly better subjective functional and aesthetic outcomes compared to LA; however, this was not found to be statistically significant. A number of authors have previously found GA and LA to be equivocal in their subjective outcomes, including a meta-analysis by Al-Moraissi and Ellis which concluded that GA could provide better outcomes but was similarly not statistically significant.,- Notably, they found GA is favorable if extensive septal work is required, the patient was uncooperative or the fracture severely displaced. In our study, patients had simple closed fractures, with no other significant bony injuries and no requirement for intraoperative instrumentation for depressed segments. Khwaja et al showed in their study that degree of nasal tip displacement and septal displacement were prognostic indicators for the rate of further corrective surgery due to persistent deformity or nasal obstruction, but the method of anesthesia used for the initial reduction was not significant. Our dissatisfaction rates across techniques were similar to other studies, who report rates ranging from 14% to 50%.-

We had a number of patients with septal deformity secondary to injury noted at their outpatient appointment, who reported poor breathing scores, and lower cartilaginous deformity with poor aesthetic scores. Manipulation under anesthesia #nasal bones is primarily aimed at addressing the bony deformity, with cartilaginous correction not possible with this technique. Patient expectations preoperatively can impact their subjective outcome; therefore, patients who have significant cartilaginous deformity in clinic, should be appropriately counseled regarding the likelihood of a successful manipulation. We feel this may have affected some of the satisfaction scores, despite a high percentage of patients stating they would still undergo the same procedure again if they had the choice in hindsight. Similarly, the differing number of these patients in each group could have impacted on the differing rates of patients who felt they required a further procedure. This would be in keeping with similar published work, which see no significant difference in the rate of septorhinoplasty or rhinoplasty between GA and LA.,,,

With the ability to make an informed decision, patients may opt for a closed manipulation to address an upper third bony deformity knowing it may not guarantee their preinjury appearance or function, or they could choose to consider a septoplasty, rhinoplasty, or septorhinoplasty to address all aspects of their injury in the future. The disadvantage of this is that most patients in UK ENT departments are assessed by a junior ENT surgeon initially, who may not have the experience to fully inform the patient of their choices.

Cost and Safety

With both methods of anesthesia, patients are primarily reviewed in the Emergency ENT Clinic, before a decision is made to proceed to MUA #nasal bones under LA on the same day or to book for a GA at a future date. The day case tariff for MUA #nasal bones under GA in our trust is set at £629.00 for those aged 19 years and over, and £776.00 for those 18 years and under. The outpatient tariff regardless of age is £121.00. Equipment to be used for the procedure itself does not differ, although there is added anesthetic equipment and staffing requirement for a GA, including theater staff, an anesthetist and recovery staff. No patients who underwent a GA required to stay overnight in our study, but there would be an additional bed cost incurred if there were any complications from the anesthetic and prolonged observation was required. There is evidently a significant added cost with GA compared to LA, and therefore, LA provides a more cost-effective alternative. There is also a theoretical risk associated with a GA; however, given the majority of our patients were young and healthy, this may be negligible., In the patients who are older with significant comorbidities this risk could prove more significant, and as a GA additionally requires fasting prior to surgery, an LA would be a much safer option. There is also no significant postprocedure recovery time associated with an LA, which increases its appeal. More procedures could be performed in a session, which provides a better service for patients and maximizes training opportunities for ENT surgeons.

With a GA, a greater number of staff members are exposed to the patient. There is a minimum of a senior and junior ENT surgeon, a senior and junior anesthetist, an anesthetic nurse and scrub nurse and circulating nurse in theaters, compared to the outpatient clinic which would have no more than a senior and junior ENT surgeon and a clinic nurse. Furthermore, as per local protocol, enhanced PPE is required to perform MUA #nasal bones in the outpatient clinic under LA, in a separate room designed to accommodate AGP, whereas under GA, at present there is no official requirement to don more than standard PPE, as patients do not routinely require airway manipulation such as intubation. Therefore, one could argue that with a smaller number of potentially exposed staff members and a requirement of enhanced PPE, LA could be a safer option.

Average Time Frames

The time from injury to procedure is shorter in the LA group, which would be logical given the absence of an added delay from outpatient appointment to GA. In our study, this pathway was shortened by approximately 2 days on average. Despite the general consensus in the United Kingdom for a 2-week window to perform a satisfactory procedure, some authors have shown good outcomes when performing MUA #nasal bones under GA, beyond this window, as late as one month., On the contrary, Sharma et al have shown that earlier manipulation confers greater satisfaction rates postoperatively. Multiple other factors may influence outcome, including previous trauma, degree of deviation, and patient expectations. In our study, we had 2 patients who presented after 30 days and had unsatisfactory aesthetic outcomes, without any significant septal deformity. Anecdotally, it follows that earlier manipulation before fusion of the nasal bones could facilitate a technically easier procedure. This would be more comfortable for the patient and is perhaps more important in an awake patient under LA. Communication with clinic schedulers and theater coordinators is paramount to ensure patients are seen within an appropriate time frame, often difficult to achieve at the best of times but particularly during the surge and peak of the pandemic.

It is worth noting that with the new measures imposed by COVID-19, theaters now have “green” COVID-19-free areas for elective patients, and patients are therefore required to have a negative COVID-19 swab at least 72 hours prior to their procedure, and to self-isolate for that time. This potentially adds further time to the GA pathway and is an added inconvenience to patients, contrary to those seen in clinic for MUA #nasal bones LA who can have the procedure done the same day with suitable PPE in place. A GA relies on patients to reliably self-isolate, which could pose a risk to staff if this is not adequately enforced.

Our pathway will now stipulate that patients with simple, closed fractures will be offered MUA #nasal bones under LA if appropriate, and aim to complete this process within 2 weeks, often at the time of review in the clinic setting thus avoiding further attendances. GA could still be used in children, uncooperative patients or if there is a significant deformity, or depressed segment requiring instrumentation assistance.

Study Limitations

We recognize the limitations to our study. We used a Likert scale to measure subjective outcomes in patients as it has been successfully used in previous studies but is subject to bias. Patients may find it difficult to adequately grade the specific issues they have with their nose on a numerical scale. As the interviews were conducted over the telephone, there may be some bias toward giving the interviewer a perceived “acceptable” score; however, this was reduced by having a standardized script to deliver the questions. A validated questionnaire delivered without an interviewer could reduce this bias. We also know that there is a disparity between what the patient thinks is acceptable subjectively and what the clinician thinks acceptable objectively, as shown by previous studies., We chose subjective scores however as we felt patient outcome measures are what drive their decision-making for further corrective surgery, more so than objective clinician assessment. The surgeons who performed the procedures were from the same department, performed in a standardized fashion and supervised by a senior surgeon, but there would be some degree of interoperator variability. It could also be argued that a longer follow-up period would yield more reliable long-term subjective outcome data, than the one month in our study, and could allow data to be gathered on further corrective surgery rates.

In conclusion, MUA #nasal bones under LA could provide a safer alternative to GA in selected patients, in keeping with previous work, resulting in satisfactory breathing and aesthetic outcomes for patients, and a shorter therapeutic pathway. Junior ENT doctors should be suitably trained in providing this service in a standardized manner, with adequate senior support and PPE in place. With the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the financial burden and caseload pressure on elective theaters would be alleviated, allowing increased capacity for time-sensitive operations to take place once normality resumes. Furthermore, in the event of additional COVID-19 surges, performing procedures under LA could allow a nasal fracture service to continue, which may otherwise be required to cease. In the short term, the number of further corrective operations may be reduced; however, additional prospective studies over a longer time period are required to determine whether this translates to an overall reduction in corrective septoplasty and septorhinoplasty rates.

Authors’ Note The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Johan Bastianpillai

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5884-034X

References

- 1. Illum P, Kristensen S, Jørgensen K, Brahe Pedersen C. Role of fixation in the treatment of nasal fractures. Clin Otolaryngol. 1983;8(3):191–195.

- 2. Rajapakse Y, Courtney M, Bialostocki A, Duncan G, Morrissey G. Nasal fractures: a study comparing local and general anaesthesia techniques. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73(6):396–399.

- 3. Ridder GJ, Boedeker CC, Fradis M, Schipper J. Technique and timing for closed reduction of isolated nasal fractures: a retrospective study. Ear, Nose Throat J. 2002;81(1):49–54.

- 4. Hung T, Chang W, Vlantis AC, Tong MC, Van Hasselt CA. Patient satisfaction after closed reduction of nasal fractures. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2007;9(1):40–43.

- 5. Fornazieri MA, Yamaguti HY, Moreira JH, Navarro P, Heshiki RE, Takemoto LE. Fracture of nasal bones: an epidemiologic analysis. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;12(4):498–501.

- 6. Vilela F, Granjeiro R, Maurício Júnior C, Andrade P. Applicability and effectiveness of closed reduction of nasal fractures under local anesthesia. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;18(3):266–271.

- 7. Kapoor P, Richards S, Dhanasekar G, Kumar N. Management of nasal injuries: a postal questionnaire survey of UK ENT consultants. J Laryngol Otol. 2002;116(5):346.

- 8. Al-Moraissi EA, Ellis III E. Local versus general anesthesia for the management of nasal bone fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73(4):606–615.

- 9. Cook JA, McRae RDR, Irving RM, Dowie LN. A randomized comparison of manipulation of the fractured nose under local and general anaesthesia. Clin Otolaryngol. 1990;15(4):343–346.

- 10. Green KM. Reduction of nasal fractures under local anaesthetic. Rhinology. 2001 ;39(1):43–46.

- 11. Khwaja S, Pahade AV, Luff D, Green MW, Green KM. Nasal fracture reduction: local versus general anaesthesia. Rhinology. 2007;45(1):83–88.

- 12. Waldron J, Mitchell D, Ford G. Reduction of fractured nasal bones; local versus general anaesthesia. Clin Otolaryngol. 1989;14(4):357–359.

- 13. Murray J, Maran A. The treatment of nasal injuries by manipulation. J Laryngol Otol. 1980;94(12):1405–1410.

- 14. Crowther JA, O’Donoghue GM. The broken nose: does familiarity breed neglect? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1987;69(6):259–260.

- 15. Courtney M, Rajapakse Y, Duncan G, Morrissey G. Nasal fracture manipulation: a comparative study of general and local anaesthesia techniques. Clin Otolaryngol. 2003;28(5):472–475.

- 16. Watson D, Parker A, Slack R, Griffiths M. Local versus general anaesthetic in the management of the fractured nose. Clin Otolaryngol. 1988;13(6):491–494.

- 17. Braz LG, Braz DG, Cruz DS, Fernandes LA, Módolo NS, Braz JR. Mortality in anesthesia: a systematic review. Clinics. 2009;64(10):999–1006.

- 18. Perkins V, Vijendren A, Egan M, McRae D. Optimal timing for nasal fracture manipulation—Is a 2-week target really necessary? A single-centre retrospective analysis of 50 patients. Clin Otolaryngol. 2017;42(6):1377–1381.

- 19. Renkonen S, Vehmanen S, Mäkitie A, Blomgren K. Nasal bone fractures are successfully managed under local anaesthesia–experience on 483 patients. Clin Otolaryngol. 2016;41(1):79–82.

- 20. Sharma SD, Kwame I, Almeyda J. Patient aesthetic satisfaction with timing of nasal fracture manipulation. Surg Res Pract. 2014;2014.

- 21. Dickson M, Sharpe D. A prospective study of nasal fractures. J Laryngol Otol. 1986;100(5):543–552.