Introduction

Myiasis is the infestation of live vertebrates with dipterous larvae, at least transiently, feeding on the host’s dead or living tissue, bodily fluids, or ingested food. Predisposing factors for myiasis in humans are low socioeconomic status, poor personal hygiene, mental retardation, child neglect, old age, and diabetes mellitus., Myiasis can cause fatal complications, although it is a self-limiting disease since the eggs fully mature within 4 to 7 days after which the maggots leave their host.-

Aural myiasis is the infestation of the external and/or middle ear. Flies lay eggs even during flight and are attracted by odoremanating from the ear, and chronic lesions, especially chronic suppurative otitis media, contribute to this., The extent of infestation depends on the fly species, host, and environment, together with the immune response of the host. Most cases of aural myiasis do not require surgery. A review of 45 aural myiasis cases reported in 34 articles found that 88.9% of patients do not require surgery.

Case Report

A 29-year-old woman, accompanied by her father, presented at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology with smeary otorrhoea on the left side, present for 7 days. A blood-tinged discharge and something living were observed in the external ear canal. Since the patient had congenital mental retardation, her father reported that she did not complain of any illness, except for occasionally scratching the ear. There was a history of chronic otitis media and no history of otologic trauma.

On clinical examination, several active maggots and purulent secretion were found to completely fill the left external auditory canal (Figure 1). The right ear was normal. Four maggots were removed immediately after suction of the purulent secretion. The external ear canal was suffused with 1% tetracaine for 5 minutes, and then 8 additional maggots were removed with fine forceps under a microscope. The ear was irrigated with 3% hydrogen peroxide and warm saline solution. Otomicroscopic examination revealed mild edema and erythema of the external auditory canal, a small central perforation of the tympanic membrane, and no larvae or pathological findings in the middle ear other than mucous edema (Figure 2). The left ear was irrigated completely again and no more eggs or larvae were found. The patient was then treated with Levofloxacin ear drops (0.5%, 5 mL) and oral antibiotic (Cefdinir 0.1 g 3 times per day) to prevent secondary infection. Symptoms were relieved in 3 days. Temporal area computed tomography (CT) was performed to evaluate the peripheral tissues. Computed tomography revealed decreased aeration corresponding to soft tissue density, consistent with pus on the left side, but no signs of larvae or bone destruction in the air chamber area of the temporal bone were noted on the left side; the structures of the middle ear (ossicles) were evaluated as normal on the right side. The remainder of the skull was unremarkable on CT.

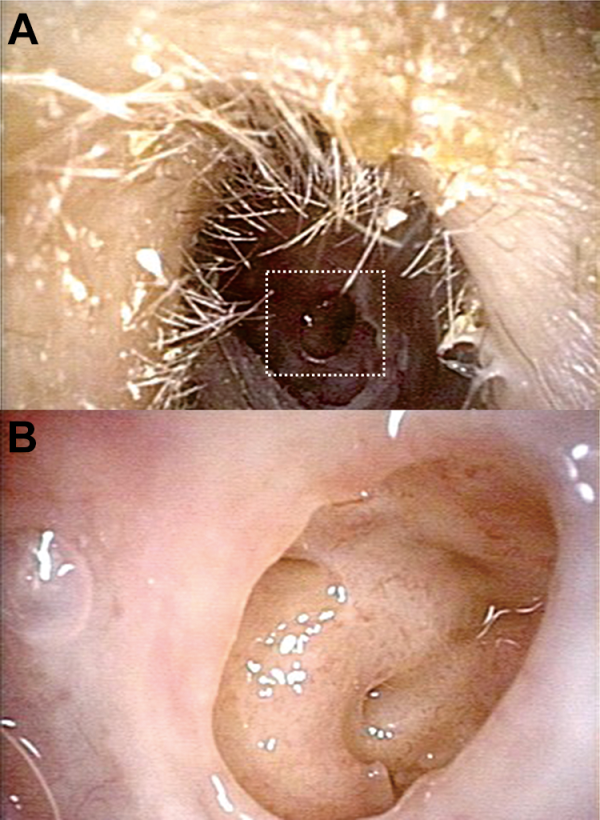

Figure 1

Several active maggots and purulent secretion completely filled the left external auditory canal (arrow).

Figure 2

Otomicroscopic examination revealed: (A) a small central perforation of the tympanic membrane, (B) no larvae or pathological findings in the middle ear except mucous edema.

Follow-up examinations revealed no remaining infestation, and the perforated tympanic membrane healed gradually. The 12 visible living maggots were preserved in 70% ethanol. The whitish maggots were approximately 5 to 8 mm long. To investigate the possible cause of the infestation, the patient’s father inspected her living environment and found 2 species of fly, which were identified as Lucilia sericata and flesh fly separately.

Discussion

Myiasis is derived from the Greek term “myia,” meaning “fly.” Entomologically, myiasis is divided into 3 types: obligatory, facultative, and accidental myiasis. Clinical cases of myiasis are classified according to the anatomic site affected: cutaneous myiasis, myiasis of external orifices (nose and paranasal sinuses, and outer ear) or internal organs, and invasion of head cavities., Myiasis of aural, nasal, ocular, oral, vaginal, urinary, and intestinal tracts has been reported. With improvements in living standards, human myiasis is less common than formerly. Aural myiasis occurs most often in children younger than 10 years of age. A retrospective analysis of 254 cases of myiasis concluded that 37.9% occurred in children. In adults, those with mental retardation are particularly susceptible,, as in our case. Our patient’s low level of personal hygiene allowed the maggots a chance to grow. Her level of intelligence meant that she was either unware of the lesion or unable to describe the condition. Human myiases have biological, medical, and public health significance. Aural myiasis should arouse the attention of doctors (especially otolaryngologists), as well as necessitate social care for special people (mental retardation, neglected people).

The clinical symptoms of aural myiasis include foreign body sensation, itching, otalgia, purulent or blood-tinged aural discharge, tinnitus, vertigo, hearing impairment, and perforation of the tympanic membrane., In children, irritability, scratching the ears involved, and otorrhea are more common. In our case, the presence of otorrhea and maggots should have been easily detected but were ignored. It must be noted that the maggots can inhabit a normal ear.

Removal of maggots is the primary task for the management of myiasis. It is important to avoid crushing any flies directly while removing them, as this can leave eggs. It is not advisable to kill the maggots in the ear, as this will make them difficult to find, and any dead maggots remaining in the ear can cause a foreign body reaction. Irrigation of the ear canal with 70% ethanol, physiologic saline, urea, oil drops, dextrose, creatinine, iodine saline, and topical ivermectin have all been used to help remove remaining larvae,, with ivermectin being the most commonly used and effective drug. Local anesthetic can be used to restrict the movements of larvae and avoid local irritation. Local and systemic therapy is recommended following manual cleaning., For those with ear infections, as in our case, topical antibiotics are a must. To treat infestation of the deep mastoid cavity, the following points should be noted: (1) Direct irrigation is not a suitable approach, as it may move the maggots deeper; (2) Patients with a long course of disease, a large number of maggots or severe local damage, especially those with intracranial complications, should be treated surgically as soon as possible; (3) CT is an indispensable tool, as it can evaluate possible complications; hearing should also be tested if possible; and (4) The case must be reviewed after surgical operation.

Maggots are considered disgusting and cause infections in many organs, sometimes leading to serious complications. The mortality rate is as high as 8% when myiasis of the ear and nose lead to infestation of the brain. In contrast, maggot debridement therapy (MDT) is an effective and reliable method of wound healing through 3 possible mechanisms: debridement, disinfection, and growth-promoting activity.

The carrion-breeding habit of maggots has been known for centuries. It has been observed in MDT of infected wounds after transplantation that maggots can reach necrotic tissue and clean tiny areas without damaging the healthy tissue. Proteolytic enzymes secreted by maggots cause liquefaction of necrotic tissue, and 3 proteolytic enzymes have been identified in maggot excreta/secretion (ES): serine proteolytic enzyme, aspartic acid proteolytic enzyme, and metalloproteinase. Maggots have a unique immune system, enabling them to devour and kill bacteria without becoming infected. Excreta/secretion has inhibitory effects on both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Meanwhile, the physical stimulation of maggots crawling on the surface of a wound promotes the growth of granulation tissue. The peptide fraction of maggot ES has also been reported to have antitumor activity and immunomodulatory effects. Maggot debridement therapy provides a feasible method of treating difficult wounds and overcoming bacterial resistance, as well as providing a new approach to the treatment of tumors. Although we may have to treat accidental cases of myiasis in the clinic, we should also know enough about the organisms involved in myiasis and use MDT rationally.

Authors’ Note Y.W. and Y.S. contributed equally to this work. A legally authorized representative of the patient (her father) gave written consent for the publication of this case report.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Yu Sun

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1771-3715

References

- 1. Zumpt F. Myiasis in man and animals in the old world. In: A Text Book for Physicians, Veterinarians and Zoologists. Butterworths and Co. Ltd, 1965: p.109.

- 2. Mengi E, Demirhan E, Arslan IB. Aural myiasis: case report. North Clin Istanb. 2015;1(3):175–177.

- 3. Bayindir T, Miman O, Miman MC., et al. Bilateral aural myiasis (Wohlfahrtia magnifica): a case with chronic suppurative otitis media. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2010;34(1):65–67.

- 4. Kaczmarczyk D, Kopczyński J, Kwiecień J., et al. The human aural myiasis caused by Lucilia sericata. Wiad Parazytol. 2011;57(1):27–30.

- 5. Francesconi F, Lupi O. Myiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25(1):79–105.

- 6. Cetinkaya M, Ozkan H, Köksal N., et al. Neonatal myiasis: a case report. Turk J Pediatr. 2008;50(6):581–584.

- 7. Yuca K, Caksen H, Sakin YF., et al. Aural myiasis in children and literature review. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2005;206(2):125–130.

- 8. Jervis-Bardy J, Fitzpatrick N, Masood A., et al. Myiasis of the ear: a review with entomological aspects for the otolaryngologist. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2015;124(5):345–350.

- 9. Hope FW. On insects and their larvae occasionally found in the human body. Trans R Entomol Soc Lond 1840;2:256–271.

- 10. Singh I, Gathwala G, Yadav SP., et al. Myiasis in children: the Indian perspective. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1993;25(1-3):127–131.

- 11. Singh A, Singh Z. Incidence of myiasis among humans—a review. Parasitol Res. 2015;114(9):3183–3199.

- 12. Ata N, Güzelkara F. Aural Myiasis in an Infant. J Craniofac Surg. 2017;28(1):e89–e90.

- 13. Uysal S, Ozturk AM, Tasbakan M., et al. Human myiasis in patients with diabetic foot: 18 cases. Ann Saudi Med. 2018;38(3):208–213.

- 14. Shi E, Shofler D. Maggot debridement therapy: a systematic review. Br J Community Nurs. 2014;19(12):S6–13.

- 15. Mumcuoglu KY, Ingber A, Gilead L., et al. Maggot therapy for the treatment of intractable wounds. Int J Dermatol. 1999,38(8):623–627.

- 16. Wang J, Wang S, Zhao G., et al. Treatment of infected wounds with maggot therapy after replantation. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2006;22(4):277–280.

- 17. Chambers L, Woodrow S, Brown AP., et al. Degradation of extracellular matrix components by defined proteinases from the greenbottle larva Lucilia sericata used for the clinical debridement of non-healing wounds. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148(1):14–23.

- 18. Mumcuoglu KY, Miller J, Mumcuoglu M., et al. Destruction of bacteria in the digestive tract of the maggot of lucilia sericata (Diptera: Calliphoridae). J Med Entomol. 2001;38(2):161–166.

- 19. Sun HX, Chen LQ, Zhang J, Chen FY. Anti-tumor and immunomodulatory activity of peptide fraction from the larvae of Musca domestica. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014,153(3):831–839.