Globally, female sex workers (FSWs) are disproportionately adversely affected by the HIV epidemic (). In India, the country with the world’s third largest HIV epidemic (), HIV prevalence among FSWs has been estimated to range between 2% and 38% (). HIV prevalence in one of the worst affected states, Karnataka, is reportedly around 1% in the general population, but has reached over 25% among FSWs in districts such as Bagalkote in the north of Karnataka (); HIV prevalence among clients of FSWs in the district is 13% ().

There are more than 5,000 FSWs in Bagalkote district; the majority of them (80%) are from rural areas and are Devadasi sex workers (). Devadasi women form a culturally distinct community of sex workers in India, with specific traditions and practices: Devadasis are girls and women who are dedicated, through marriage, to the goddess Yellamma, as well as to other gods and goddesses. These girls and women subsequently provide sexual services to patrons of the temples (; ). Devadasis begin sex work at a much younger age than other FSWs (mean: 15-16 years vs. older than 21 years for non-Devadasi girls; ). The practice was outlawed in 1988, and consequently Devadasis and their sexual services have become increasingly commercialized as a result of being driven underground—even while the tradition continues to confer on their sex work a veneer of social and cultural sanction not afforded to other FSWs ().

In 2003-2004, the AVAHAN program, funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) and implemented by the Karnataka Health Promotion Trust (KHPT), was rolled out in 20 of the 27 districts across Karnataka, aiming to reduce HIV prevalence among populations at high risk of HIV, including FSWs and men who have sex with men (). Initial workshops with FSWs identified violence by police, clients, and others as a key concern for women; the AVAHAN program therefore contained a component to address violence against FSWs perpetrated by clients and police as part of comprehensive HIV prevention programming (). Studies have shown that sex workers who experienced violence visited clinics less often, had lower condom use, and experienced more condom breakage, increasing the risk of HIV (). Mathematical modeling suggests that a reduction in violence against FSWs would result in a 25% reduction in incident HIV infections ().

Following AVAHAN, data indicated an increase in condom use and a decrease in violence perpetrated by clients and HIV rates (; ; ). It became evident, however, that the prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV) was high in relationships between FSWs and their intimate partners (IPs) and inconsistent condom use remained a major concern within these relationships (; ; ; ; ; ). Sixty percent of FSWs in Bagalkote district have at least one IP; sexual activity in these relationships is high (sexual intercourse 9-10 times per month) and violence is present in one out of four relationships ().

While the majority of the literature on FSWs and HIV risk focuses on FSWs and their paying clients (; ), there is a growing body of evidence exploring a range of individual and structural HIV risk factors that are affected by FSW–IP relationships. Condom use with IPs has been reported to be more inconsistent than with paying clients. In a community-based cohort study in Vancouver, Canada, inconsistent condom use was significantly associated with FSWs having a cohabiting or noncohabiting IP, financially supporting an IP, and experiencing IPV (). Likewise, in a cross-sectional survey of FSWs in three states in India, 87% of FSWs with an IP reported inconsistent condom use with them; women with IPs were more likely to be street-based, have higher levels of debt, and be categorized as vulnerable ().

Inconsistent condom use with IPs may not, however, solely be due to vulnerability, violence, and economics. A number of studies attribute inconsistent condom use between FSWs and their IPs to the positive aspects of these relationships: to love (), to trust and length of the relationship (), and to the idea that condoms prevent emotional and sexual intimacy (; ). A qualitative study undertaken in Mumbai, India, found that FSWs were looking for protection and emotional support from relationships with IPs and that emotional investment was undermined by condom use, which demoted the relationship from that of lovers back to that of FSW-and-client; rejecting condoms therefore bestows a quasi-marital legitimacy on the relationship (). In addition, women may not use condoms with their IPs if they are wanting to get pregnant (; ). While there is a paucity of evidence regarding the pregnancy intentions of FSWs in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), a study with Devadasi women in north Karnataka found that although these women are unable to marry, they remain subject to the social expectation that the “ideal” woman bears children to her husband. Consequently, they may feel under particular pressure to have children with their IPs and forgo the use of condoms ().

Studies exploring IPV suggest that, globally, FSWs are better able to negotiate safer sex and protect themselves against violence from clients rather than from their IPs (). In an observational study in Cambodia, sexual violence predicted an increased odds of inconsistent condom use with IPs (). Similarly, in a cross-sectional study of FSWs living on the U.S.–Mexico border who use drugs, inconsistent condom use was found to be significantly associated with IPV and victimization (). Studies have explored the importance of gender norms in increasing both IPV and HIV risk in FSW–IP relationships. A qualitative study with FSWs in India found that FSWs adhered to cultural gender norms when negotiating condom use with IPs, but were more successful in negotiating condom use with their clients (). Furthermore, a qualitative study in northern Karnataka examined how FSWs and their IPs describe their experience and understanding of IPV: The contravention of gender norms constituted an important trigger of violence ().

The literature, therefore, indicates that HIV risk for FSWs is shaped by a variety of factors, including economics, love, and gender norms. A deeper understanding of how these factors are interwoven and structure HIV risk for FSWs is lacking. Furthermore, few studies include IPs’ views and perspectives. This makes it difficult to design appropriate strategies for FSWs to address violence and the lack of condom use. This study, therefore, undertook participatory workshops with FSWs and their IPs in two of six talukas (administrative units) in Bagalkote district, north Karnataka, to explore three aspects of their relationships: how they understand and interpret their relationships, including the role of love and trust; the reasons for not using condoms in these relationships; and the role of violence and its consequences. The study findings were used to design intervention programs with FSWs and their IPs that aim to reduce violence and increase condom use within these relationships ().

Method

Sample

KHPT worked in partnership with Chaitanya AIDS Tadegatwa Mahila Sangha (CATMS), a FSW-led community-based organization (CBO) working in the region for more than 10 years. The CBO recruited and mobilized FSW and IP participants for the research.

A total of 68 respondents from two selected talukas (Mudhol and Jamkhandi) participated in the study: 31 FSWs and 37 IPs of FSWs. FSW participants were included in the study if they were a practicing sex worker (had traded sex for money in the last month), identified herself as female, and had (at least one) current intimate male sex partner. IPs were included if they had (at least) one FSW as a current intimate sex partner, identified themselves as an “intimate sex partner” or a “lover” or as a non–commercial sex partner (a partner whom the sex worker will not define as her current commercial client, although he could have been her client in the past). IPs were only included with the permission of the FSW.

Further purposive sampling was undertaken based on marital status, occupation, whether they had children, and age, to ensure a comprehensive sample. Most of the IPs who participated in the study worked as laborers, or on farms. Some also worked in shops or tailoring units, or owned small businesses.

Methodology

Participatory action research provided the conceptual framework for the study (). Participants were invited for 3-day residential workshops (separately: one for sex workers and one for their IPs), organized 1 month apart. The workshop with sex workers was undertaken prior to the workshop with IPs; the workshops were conducted separately to create an environment of comfort and freedom and to avoid the two groups affecting each other’s responses. The CBO was involved in designing the workshops and analysis of the research.

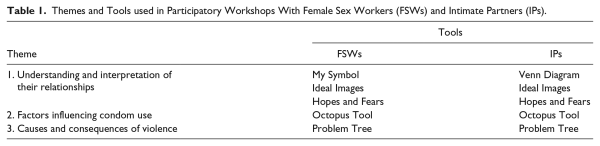

To engage with the participants and encourage them to discuss what are considered sensitive topics, participatory tools were used and significant time was spent undertaking ice breakers and energizers. The study used Participatory Learning and Action Tools, borrowed or adapted from Tools Together Now () and Stepping Stones—an Indian Adaptation (). A total of five tools were used with FSWs and six tools were used with IPs to conduct the assessment. The themes and the tools of the study are summarized in Table 1. “Exploring Tools” such as Symbols, Venn Diagrams, and Hopes and Fears were used for observation and reflection of experiences, and “Analyzing Tools” such as Octopus Diagrams and Problem Trees were used to identify linkages and perceptions, and to explore relationships ().

FSWs were grouped based on their age and whether they had children. One group consisted of women younger than 25 years of age who did not have children, the second and third groups consisted of FSWs who had children and were mostly older than 25 years of age. The majority of the participants were Devadasis (26/33). Nineteen FSWs had only one IP while 11 FSWs had two current IPs and one had three current IPs. IPs were grouped depending on age and marital status: Group 1 comprised 10 unmarried IPs and Group 2 comprised 8 IPs younger than 25 years of age, most of whom were married (6/8). Groups 3 and 4 consisted of married IPs; Group 3 were men aged between 25 and 35 years, and Group 4 were men aged older than 35 years. No incentives were given for participation, beyond the residential component of the workshop and travel reimbursement/provision.

Participatory Approaches

Participatory assessment and learning techniques enable the collection of a range of views and experiences ()—not just from dominant voices —and allows researchers to question established interpretations of lived experiences. These tools also enable discussion of issues such as violence from different perspectives, for example, the individual and the community. Unlike many research methods that require individuals to talk about themselves, participatory approaches enable respondents to talk indirectly about topics, for example, by referring to “the community” or “people like us.” Formalizing the participation of FSWs and their IPs also ensures that they, rather than their project leaders, identify problems and solutions, building motivation to act on the topics discussed. Such tools can be used throughout the life cycle of a program—which is important as, for example, the nature of IPV can change over time.

Data Analysis

Data analysis focused on the three thematic areas: how FSWs and IPs understand and interpret their relationships, including the role of love and trust; factors influencing the use of condoms in these relationships; and the role of violence and its consequences. During the sessions, facilitators took detailed notes when each group presented the discussions produced by the tools, as well as noted the participants’ interpretation of these exercises. At the end of each day, group facilitators together with the CBO leaders (who were not participants) and the research team analyzed these notes. Findings from these analysis sessions were then used in workshop sessions the following day to prompt questions, to develop themes, and to generate a deeper understanding of the lived realities of the FSWs and IPs. Notes from all the sessions were used to conduct analysis in the three thematic areas.

Consent and Confidentiality

As the workshop focused on sharing sensitive topics, informed consent was obtained from participants: Consent forms were read out to the participants in the local language (Kannada). Participants were assured that their participation was voluntary. Anonymity was ensured by using an ID number instead of names. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Board of the St. John’s Medical College and Hospital, Karnataka (IERB Study Reference Number 70/2012).

Results

Understanding and Interpretation of the Relationships Between FSWs and IPs

Although FSWs and IPs stated they valued their relationships, there was great disparity in the level of commitment that FSWs and IPs were prepared to offer one another. FSWs desired greater commitment than IPs were often willing to give, leaving FSWs with less power and vulnerable in the relationship.

The tool “My Symbol,” where FSWs drew pictures depicting themselves and their IP (Figure 1), and the tool “Ideal Images” were used to explore FSWs’ perceptions of themselves and their IPs as well as expectations of their relationship. With IPs, the tools, “Ideal Images” and “Venn Diagram” were used to understand their perception and expectations from their FSW partners. There was a clear divide in the way FSWs and IPs perceived themselves and each other. FSWs represented themselves using symbols such as flowers, cows, and thalis, representing beauty, femininity, or marriage (thalis are neck ornaments symbolizing marriage). They stated that their ideal IP should take responsibility for their children, in terms of health care and education, and for their parents in terms of caring for them in old age. Importantly, IPs should trust their FSWs and acknowledge the FSW as their wife in public. The symbols FSWs drew to represent their IPs, however, such as snake and monkey, revealed that these relationships are characterized by violence and dominance (Figure 1).

I think my lover is like a snake, because he is very poisonous and I am afraid of him. When he gets angry, he hisses like a snake. But just like the way we worship a snake, I worship him too. (35-year-old FSW)

When I told my lover that I am going for a training program, he ordered me not to attend the training as he doubted whether I would really attend the training program or use it as an excuse to meet other clients. The whole night, he abused me over the phone and threatened to leave me for not obeying his orders. I feel my lover should have more trust and confidence in me. (20-year-old FSW)

Figure 1

Me and my intimate partner: A drawing by an FSW respondent.

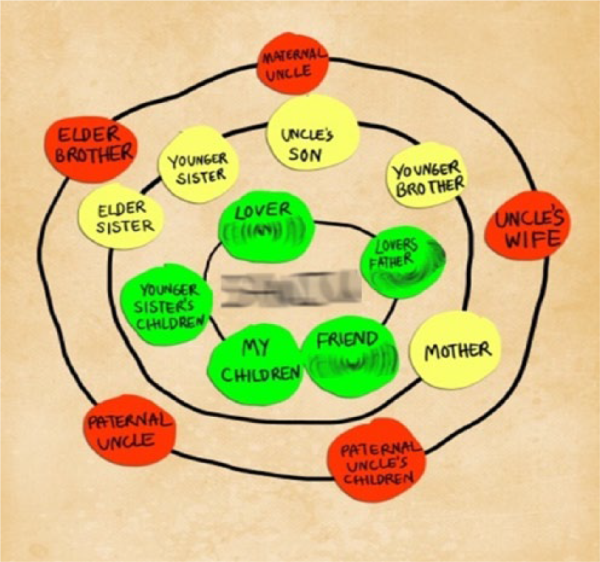

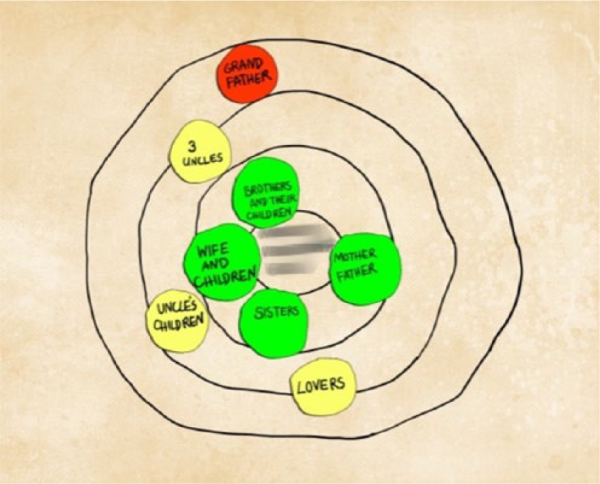

When drawing Venn diagrams to illustrate the importance of family and FSWs in their lives, most unmarried IPs placed the FSWs near the center of the diagram, indicating a high level of importance (Figure 2). In contrast, most married IPs placed their families in the center and the FSWs in outlying circles, indicating a lower level of importance (Figure 3). Both married and unmarried IPs distinguished the role of wife from that of their FSW lover: While both wives and lovers should be loyal, possess a good character, dress “decently” and have a caring nature, FSW lovers were also expected to provide sexual satisfaction, pleasure, and romance.

Both my wife and my lover have to be loyal to me. If I ever come to know that my lover is going with other men, I will kill her. (25-year-old married IP)

Figure 2

Important people in my life: A drawing by an unmarried intimate partner.

Figure 3

Important people in my life: A drawing by a married intimate partner.

FSW lovers were expected to be available whenever the IP wanted sex, and not to ever refuse sex. IPs expected FSW lovers to give them the emotional support that they did not get from their wives, and they expected to receive money from FSWs whenever they needed it. While some IPs considered the FSWs’ children as their own, others said that they cannot be expected to accept “fatherly” responsibilities toward children of their FSW lovers.

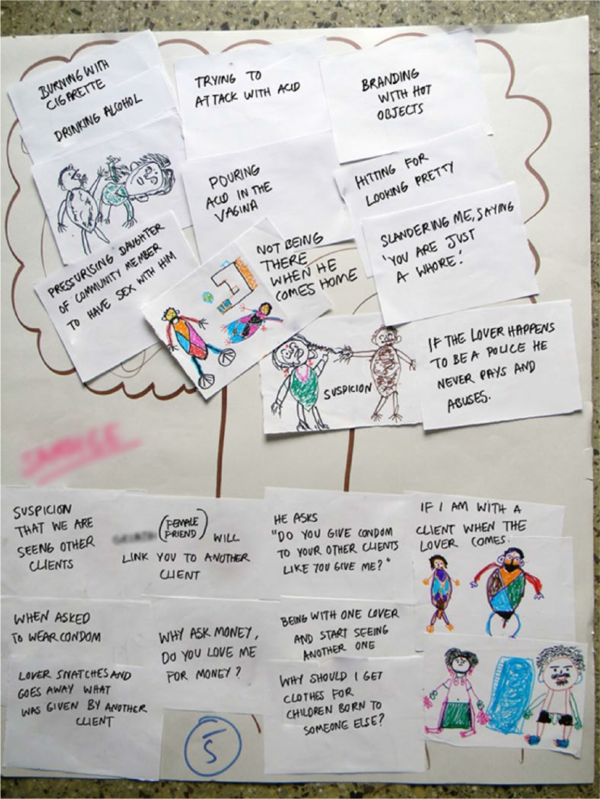

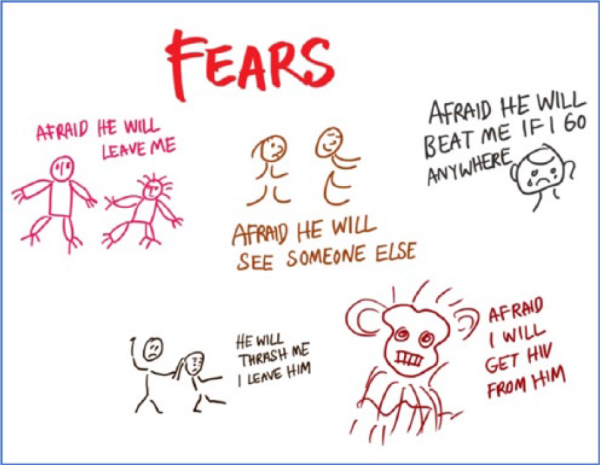

The tool “Hopes and Fears” was used with FSWs and IPs to understand how they perceive the future of their relationship. Discussions around FSWs’ and IPs’ hopes and fears for their relationships revealed that both mutually feared the end of the relationship and hoped that the relationship could provide lasting love and loyalty. Even though FSWs feared violence from their IPs (Figure 4), they also clearly distinguished the love, commitment, and respect they found in these relationships from the commercial relationships they had with clients. FSWs’ hopes for the future hinged on legitimization of their social position through the relationship, through the IPs’ commitment and by having children together. FSWs feared, however, being caught soliciting other clients (a financial necessity) as well as contracting sexually transmitted infections such as HIV. IPs also feared contracting HIV, and yet worried that they would be compelled to wear condoms.

Figure 4

Problem tree: Causes and impact of violence according to FSWs.

Factors Influencing the Use of Condoms

The research found that while fear of violence was a significant factor that influenced the use of condoms, more important factors were love and trust—the belief that one’s partner was faithful—as well as the perceived quasi-marital legitimacy that unprotected sex bestowed on the relationship.

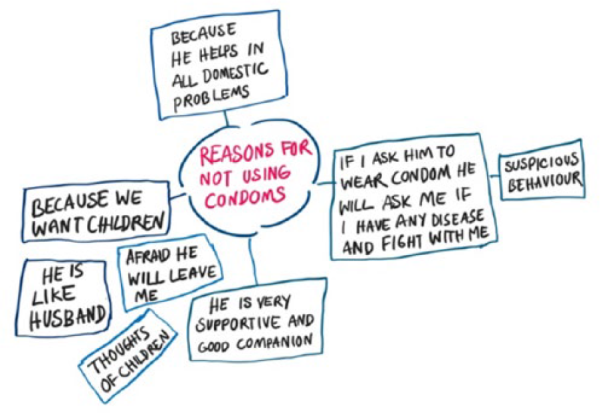

The “Octopus Tool” (brainstorm) was used to explore the factors influencing the use of condoms. The discussions revealed that while fear of violence discouraged the sex workers from negotiating condom use with IPs, FSWs also stated that these relationships were akin to matrimonial relationships in which condoms are not used (Figure 5). They stated that IPs did not expect FSWs to solicit clients once in a relationship with the IP, and that requesting condom use would suggest that they were still doing so—which would anger IPs. FSWs also expressed their desire to have children with their IPs, often because they believed the IP would love them better and be more committed to them if they bore his children.

I have used condom with my lover when I used to go to her as a client. But now that I am her lover, I do not feel the necessity to use condoms as I trust that she will not have sex with anyone else other than me. (36-year-old IP)

Figure 5

Why we don’t use condoms: An illustration by FSWs.

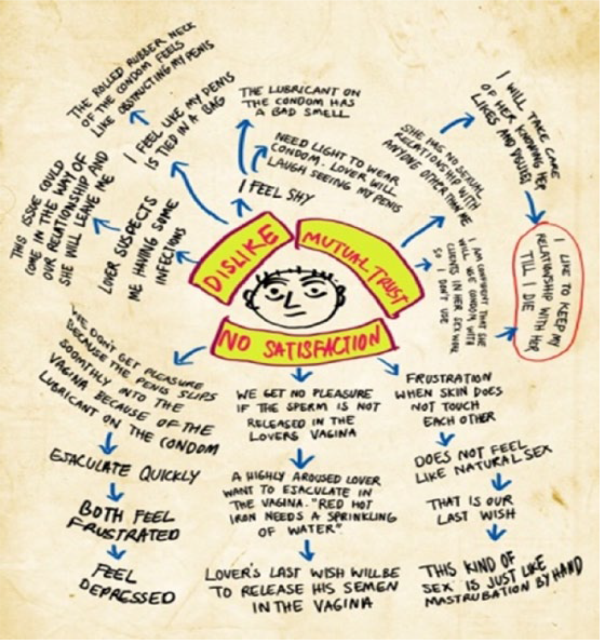

IPs reported that while their relationship with their FSW lover was not exactly akin to a matrimonial relationship, they still had exclusive rights to have unprotected sex with FSWs. Any discussion of condom use therefore undermined the relationship (Figure 6). The tool “Secret Ballot” revealed that the most common reason for the nonuse of condoms reported by IPs was that they trusted their FSW lovers and had affection for them. IPs also reported that for them, a significant factor in the nonuse of condoms was that they were a cumbersome barrier to sexual pleasure and would only be used during menstruation or to prevent pregnancy.

My intimate partner does not get satisfaction if he uses a condom. He says that he is my regular partner and hence has a right to have sex with me without a condom. (20-year-old FSW)

It is so disgusting and embarrassing to remove the messy condom and throw it away after the act. (38-year-old married IP)

Figure 6

Reasons why we don’t use condoms: An illustration by intimate partners.

Causes and Consequences of Violence

FSWs and IPs reported that violence was seen as a norm in a marital relationship and was therefore tolerated in these relationships (which tried to imitate a marital relationship) in order to avoid the relationship coming to an end. Violence was prompted by jealousy and insecurity, negotiating condom use, FSWs demanding money from their IPs, FSWs expecting IPs to take care of their children, and FSWs soliciting clients (Figure 7).

Figure 7

What FSWs fear most in their relationships.

The “Problem Tree” tool was used to explore the issue of violence, listing the root causes and the branching consequences of violence and conflict. Violence against FSWs was often severe, and included throwing acid on the FSW, burning her with cigarette butts, and beatings. FSWs also reported that violence often took the form of IPs demanding to have sex with the FSW’s daughter or sister.

I had gone for training for 3-4 days, he asked me where I had gone, and whom I met, and what did I do there. He was not satisfied with my answer, so he asked me to prove my love toward him by putting my hand in the boiling oil. He said if my hand does not burn, then only it will mean I truly love him. (33-year-old FSW)

I had a major operation some time back. Doctors had advised abstinence from sex for 6 months. But he did not pay any attention to doctor’s advice and had sex with me after 3 months. . . . He just wants to show off his power over me. (35-year-old FSW)

Both FSWs and their IPs justified the acts of violence in their relationship. IPs used violence to express dominance and power while correcting the perceived shortcomings of their FSW lover. IPs reported resorting to violence following disagreements about the legitimacy of the relationship, demands for sex or for the use of condoms, suspicions about the FSWs’ fidelity, demands for gifts, and/or under the influence of alcohol. IPs also acknowledged that they felt a sense of superiority over their FSW lover and that it was permitted to use violence against them. FSWs stated that they tolerated violence out of fear of the consequences, such as more severe forms of violence from the partner, the break-up of the relationship, or even the abuse of children and other family members.

Sometimes, I see that she has more money. When I ask her where she got this money from, she stammers and lies. She sure had fun with other men! . . . So I get angry and pick up a fight. (36-year-old IP)

My lover doesn’t like me praising my wife in front of her. She always wants to be praised. This sometimes leads to arguments wherein she picks on all my previous faults. Then I may get angry and may beat her. (32-year-old IP)

In summary, FSWs expect commitment from their IPs similar to that found in a marital relationship, creating a power imbalance that leaves FSWs vulnerable. Nonuse of condoms is a marker for love and trust in these relationships and is considered to elevate the relationship to the level of a marital relationship. Violence is perpetrated by IPs to exert power and maintain dominance, and is tolerated by the FSWs as they fear losing their IP for good if they assert themselves.

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to investigate how different factors shape the intimate relationships of FSWs. The findings indicate that FSW–IP relationships are framed by dominant social norms, gender roles, and concepts of partner fidelity. FSWs reported viewing such relationships as quasi-marriages, with some of the social status that marriage affords in India. Both FSWs and IPs valued their relationships despite the high degree of violence and risks posed by low condom use. Condom use was viewed as unacceptable in these intimate relationships, and negotiation could trigger violence. Violence was common and often severe, yet viewed as justifiable by both FSWs and IPs. The findings demonstrate that HIV risk within FSW–IP relationships is shaped by the complex interplay of a range of factors: positive factors, such as a loving, trusting relationship, perversely contribute toward low condom use, which is also encouraged by societal demands for women to be married and to have children, and compounded by violence and a fear of violence. These findings are important in designing intervention strategies to address the risk and vulnerability of FSWs within intimate relationships, as part of HIV prevention programming.

Understanding and Interpretation of Their Relationships

Social and gender norms provide the framework for FSW–IP relationships: which entrench an uneven power divide between FSWs and IPs. Social and gender norms in India place women in subordinate positions with chastity, motherhood, and obedience held to be key virtues; prevailing notions of masculinity in India characterize men as providers and independent, dominant aggressors who have a variety of sexual partners (; ; ). FSWs, therefore, deviate from the feminine ideal: unchaste and engaging in “immoral” sexual practices linked with pleasure as opposed to reproduction. This study demonstrated that for FSWs, a steady and long-lasting relationship with their IPs brings the FSWs nearer to the position of a “good” woman, enabling them to simultaneously live within and outside of the prescribed feminine role. For IPs, their relationships with the FSWs gave them the emotional support and sexual satisfaction that they could not necessarily find within their marriages. IPs still expected to be dominant within the relationship, however.

For both FSWs and IPs, the positive aspects of these relationships lie in love, trust, and shared hopes for a happy future together. These aspects were complicated by the commercial nature of their relationship as well as the experience of emotional and physical violence. A qualitative study with FSWs in Karnataka similarly revealed that emotional support in these relationships was important to FSWs (). This was both undermined and strengthened by the material support provided by IPs, because such support serves as a reminder of the transactional component of the relationship while simultaneously promoting the relationship to that of a quasi-marriage: only wives or long-term partners are supported financially. The relationship was therefore both constrained and enhanced by the financial and material support provided within it.

Factors Influencing the Use of Condoms

This study demonstrated that the positive aspects of FSW–IP relationships intersect with gender norms to compound FSWs’ reluctance to negotiate condom use in intimate relationships. Positive aspects, such as love and trust, separate these relationships from ordinary client–FSW interactions, and therefore raise different behavioral expectations for both FSWs and IPs. Expectations regarding fidelity, motherhood, decision making, and power are similar to those governing matrimonial relationships, even though they do not technically enjoy the moral or legal sanction of marriage. FSWs, therefore, avoid insisting on condom use to avoid raising suspicion about their fidelity to their IP.

Furthermore, if an FSW and her IP have children together, children provide social identity and guarantee a certain status (). suggest that Devadasi in particular may feel under great social pressure to bear children because a “good” woman is one who bears children to her husband. Similarly, our study found that FSWs in these high-risk relationships perceive the potential short-term costs of separation, estrangement, and violence from their partners as being much higher than the potential long-term health costs of not using condoms. However, for IPs, it is their negative perception of condoms and the belief that the use of condoms reduces sexual pleasure that discourages condom use in these relationships. Addressing this aspect in HIV prevention programs with FSWs and IPs is therefore vital.

These findings are similar to qualitative research with FSWs in India and Mexico, which found that FSWs adhere to culture-specific gender norms in relation to condom negotiation in intimate relationships, and that positive aspects such as love and longevity influence sexual decision-making power and condom use (; ). In addition, in studies with FSWs in India and Canada, the longer FSW–IP relationships lasted, the less likely consistent condom use was (; ). Our study demonstrated that both FSWs and IPs desired a long-lasting, happy relationship, and that condom use was therefore subject to rules governing matrimonial relationships. To preserve this matrimonial status, and fearful of violence if condom use was demanded, FSWs held little sexual decision-making power. found a strong association between the nonuse of condoms and sexual decision-making power and suggested that intervention programs should focus on empowering FSWs to counter male dominance over condom-use decision making. This study, however, would suggest that it is also vital to engage with IPs in programs, and that there is common ground between IPs and FSWs that may be built on (hopes for a happy future) despite the differences in willingness and ability to commit to the relationship.

Causes and Consequences of Violence

Both FSWs and IPs stated that IPs use violence as a means to demonstrate their power and to keep the FSW in constant submission through fear. Contravening gender norms was considered a reasonable provocation for violence. For example, if a FSW solicited other clients (explained as being an economic necessity), this was construed as infidelity by her IP, and violence was regarded as a justifiable reaction. This finding is supported by two recent studies. In a qualitative study with Devadasi in north Karnataka, IPs equated dominance and aggression with masculinity, and used violence to “discipline” their partner: for example, if the FSW disobeyed him, continued to see clients, or challenged traditional gender roles (). In a separate study in north Karnataka, India, participants stated that the contravention of gender norms was viewed as a “mistake” on the part of the FSW that constituted one of the most important triggers of violence ().

Consequently, found that Devadasi women avoided condom negotiation and reporting of violence, which they perceived as potentially undermining their relationship with their IP. Blanchard found varying levels of acceptance of violence among FSWs: FSWs in this study consistently stated that violence was unacceptable—and yet continued to tolerate high levels of violence. In the context of sex work—especially among Devadasi women who are not allowed to marry—women frequently aspire to traditional marital relationships (, ). explored how for Devadasi women, despite the lack of formal legal status, these relationships were given importance and expectations that were similar to those of marriage. Acceptance of violence may, therefore, constitute further proof of the legitimacy of the relationship in a society where domestic violence is tolerated and accepted within matrimonial relationships. Fear of the partner ending the relationship (and thus the loss of matrimonial status) means that many women continue in violent and risky relationships. Although there is substantial evidence linking IPV with increased HIV risk (; ; ; ; ), violence essentially becomes the price FSWs pay for a measure of societal approval.

This study had a number of strengths and limitations. The study design and participatory methodology enabled the collection of detailed data from both FSWs and their IPs, which has subsequently been useful to inform intervention program design. Such methodology will, however, be subject to social desirability bias. In-depth longitudinal quantitative and qualitative studies are being implemented to corroborate and expand on the findings presented here. The researchers acknowledge that their own epistemological, cultural, and theoretical background may influence data collection and analysis. Additionally, the purposive sampling of the participants potentially introduces selection bias.

Conclusion

While HIV prevention programs have successfully increased condom use with clients and reduced violence against FSWs by clients, police, and gangs, inconsistent condom use and violence persists in FSWs’ relationships with their IPs. FSW–IP relationships therefore are critical in shaping HIV risk for FSWs: At the individual level, positive aspects of FSW–IP relationships discourage condom use, being loving relationships in which FSWs and IPs trust one another and are emotionally and sexually intimate. Macro-level factors magnify individual-level factors: Social norms prohibit use of condoms within marital relationships, while gender norms afford FSWs less power than their IPs and justify violence to establish IPs’ dominance. Desire to conform to the norms of marriage and procreation, in contexts where FSWs have little sexual bargaining power and are afraid of or subject to violence, compound low levels of condom use. Given that FSWs and IPs are still sexually active with other partners, this perfect storm creates a particular transmission risk for HIV.

The complex nature of these intimate relationships makes the design of interventions challenging. The promotion of greater condom use with IPs, for example, overlooks the fact that the rejection of condom use is an active choice by many FSWs, either through fear of violence or to buy greater social status in a society that punishes FSWs for living outside the feminine ideal. Not using condoms is an active choice by IPs because they trust their FSWs and associate condoms with lower levels of sexual intimacy and pleasure.

Programmatic Implications

Following the research presented in this study, interventions to address violence and condom use within FSWs’ intimate relationships have been designed by KHPT, an NGO, and CATMS, a CBO of FSWs (). The intervention works with both FSWs and IPs, and includes activities at the individual, relationship, community, and institutional (CBO) levels. Following findings from our study, the intervention was designed to actively engage with IPs as well as FSWs. The intervention included activities to challenge IPs’ negative perception of condoms and the belief that the use of condoms reduces sexual pleasure, thereby discouraging condom use in these relationships. The intervention therefore included the promotion of female condoms as an alternative to male condoms. It also worked to actively discuss and address violence within these intimate relationships. This included building on the common ground between IPs and FSWs (their hopes for a happy future) through discussions around gender roles, love, and respect within these intimate relationships.

At the individual level, the interventions work with FSWs and their IPs to improve communication within relationships and to build skills to change social and gender norms through peer group reflection sessions, as well as individual and couples counseling. The reflection workshops endeavor to make men more sensitive and responsible in their relationships and encourage them to treat FSWs with respect and as equals. The workshops also seek to empower women to recognize violence in their lives and resist it.

At the community level, the interventions focus on engaging with local communities, including leaders, families, and self-help groups to raise awareness of domestic violence and the respective laws—including The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act 2005 (PWDVA)—and to create networks of support and action within the community to address IPV. Community dialogue, street plays, folk shows, and stakeholder meetings are conducted to engage with the community.

At the institutional level, the interventions support the sex worker-led CBO in the district to strengthen their ability to address IPV, including facilitating critical thinking among members on IPV, strengthening the crisis management systems to support FSWs experiencing IPV, and making links with other women’s organizations.

This is one of the first interventions globally designed to address violence and improve condom use in FSWs’ intimate partnerships and is being evaluated using a cluster-randomized control trial design (). Although complex and challenging, addressing violence and low condom use within FSW–IP relationships is crucial for reducing vulnerability to HIV and improving the quality of these relationships and, ultimately, of women’s lives.

The authors wish to sincerely thank the Chaitanya AIDS Tadegattuwa Mahila Sangha for their contribution, as well as the communities and individuals who proposed and participated in this study.

Authors’ Note The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.K. Department for International Development or the British Academy. Mahesh Doddamane is now at FHI 360, Mumbai, India.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was conducted with support from STRIVE and funded by UK Aid from the Department for International Development (DFID). STRIVE is a DFID-funded research consortium based at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, focusing on the structural forces—in particular stigma, gender-based violence, poverty and drinking norms—that combine in different ways to create vulnerability to HIV transmission and to undermine prevention. Tara Beattie is supported by a British Academy fellowship. The interventions are funded by UK Aid from the U.K. government via the What Works to Prevent Violence against Women and Girls? Global Programme. The funds are managed by the South African Medical Research Council.

References

- Ang A., Morisky D. E. (2012). A multilevel analysis of the impact of socio-structural and environmental influences on condom use among female sex workers. AIDS and Behavior, 16, 934–942.

- Argento E., Shannon K., Nguyen P., Dobrer S., Chettiar J., Deering K. N. (2015). The role of dyad-level factors in shaping sexual and drug-related HIV/STI risks among sex workers with intimate partners. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 157, 166–173.

- Bandewar S. V., Bharat S., Kongelf A., Pisal H., Collumbien M. (2016). Considering risk contexts in explaining the paradoxical HIV increase among female sex workers in Mumbai and Thane, India. BMC Public Health, 16, 85. doi:

- Baral S., Beyrer C., Muessig K., Poteat T., Wirtz A. L., Decker M. R., . . . Kerrigan D. (2012). Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet: Infect Diseases, 12, 538–549.

- Beattie T. S., Bhattacharjee P., Isac S., Mohan H. L., Simic-Lawson M., Ramesh B. M., . . . Heise L. (2015). Declines in violence and police arrest among female sex workers in Karnataka state, south India, following a comprehensive HIV prevention programme. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 18, 20079. doi:

- Beattie T. S., Bhattacharjee P., Ramesh B. M., Gurnani V., Anthony J., Isac S., . . . Moses S. (2010). Violence against female sex workers in Karnataka state, south India: Impact on health, and reductions in violence following an intervention program. BMC Public Health, 10, 476. doi:

- Beattie T. S., Isac S., Bhattacharjee P., Javalkar P., Davey C., Raghavendra T., . . . Heise L. (2016). Reducing violence and increasing condom use in the intimate partnerships of female sex workers: Study protocol for Samvedana Plus, a cluster randomised controlled trial in Karnataka state, south India. BMC Public Health, 16, 660. doi:

- Bhattacharjee P., Abraham C., Girish M. (2004). Stepping Stones: A training package on HIV/AIDS, communication and relationship skills. Bangalore, India: ICHAP and Action Aid.

- Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. (2009). Managing HIV prevention from the ground up: AVAHAN’s experience with peer led outreach at scale in India. New Delhi, India: AVAHAN.

- Blanchard A. K. (2015). A community-based qualitative study to explore the experience and understandings of intimate partner violence among female sex workers and their intimate partners in Karnataka, India (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Manitoba, Manitoba, Canada.

- Decker M. R., Wirtz A. L., Baral S. D., Peryshkina A., Mogilnyi V., Weber R. A., . . . Beyrer C. (2012). Injection drug use, sexual risk, violence and STI/HIV among Moscow female sex workers. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 88, 278–283.

- Decker M. R., Wirtz A. L., Pretorius C., Sherman S. G., Sweat M. D., Baral S. D., . . . Kerrigan D. L. (2013). Estimating the impact of reducing violence against female sex workers on HIV epidemics in Kenya and Ukraine: A policy modeling exercise. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 69(Suppl. 1), 122–132.

- Deering K. N., Bhattacharjee P., Bradley J., Moses S. S., Shannon K., Shaw S. Y., . . . Alary M. (2011). Condom use within non-commercial partnerships of female sex workers in southern India. BMC Public Health, 11(Suppl. 6), S11. doi:

- Deering K. N., Boily M. C., Lowndes C. M., Shoveller J., Tyndall M. W., Vickerman P., . . . Alary M. (2011). A dose-response relationship between exposure to a large-scale HIV preventive intervention and consistent condom use with different sexual partners of female sex workers in southern India. BMC Public Health, 11(Suppl. 6), S8. doi:

- Deering K. N., Shaw S. Y., Thompson L. H., Ramanaik S., Raghavendra T., Doddamane M., . . . Lorway R. (2015). Fertility intentions, power relations and condom use within intimate and other non-paying partnerships of women in sex work in Bagalkot District, South India. AIDS Care, 27, 1241–1249.

- Draughon Moret J. E., Carrico A. W., Evans J. L., Stein E. S., Couture M. C., Maher L., Page K. (2016). The impact of violence on sex risk and drug use behaviors among women engaged in sex work in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 161, 171–177.

- Gupta G. R. (2002). How men’s power over women fuels the HIV epidemic. British Medical Journal, 324, 183–184.

- Gurnani V., Beattie T. S., Bhattacharjee P., Mohan H. L., Maddur S., Washington S., . . . Blanchard J. F. (2011). An integrated structural intervention to reduce vulnerability to HIV and sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers in Karnataka state, south India. BMC Public Health, 11, 755. doi:

- India–Canada Collaborative HIV/AIDS Project. (2003). Female sex work in Karnataka: Patterns and implications for HIV prevention. Bangalore, India: Author.

- India Health Action Trust. (2010). HIV/AIDS situation and response in Bagalkot district: Epidemiological appraisal using data triangulation. Bangalore, India: Author.

- Isac S., Ramesh B. M., Rajaram S., Washington R., Bradley J. E., Reza-Paul S., . . . Moses S. (2015). Changes in HIV and syphilis prevalence among female sex workers from three serial cross-sectional surveys in Karnataka state, South India. BMJ Open, 5(3), e007106. doi:

- Jewkes R. K., Levin J. B., Penn-Kekana L. A. (2003). Gender inequalities, intimate partner violence and HIV preventive practices: Findings of a South African cross-sectional study. Social Science & Medicine, 56, 125–134.

- Karnataka Health Promotion Trust. (2010). Integrated behavioural and biological assessment: Repeat surveys to assess changes in behaviour and prevalence of HIV/STIs in populations at risk of HIV. Bangalore, India: Author.

- Khan S., Lorway R., Chevrier C., Dutta S., Ramanaik S., Roy A., . . . Becker M. (2017). Dutiful daughters: HIV/AIDS, moral pragmatics, female citizenship and structural violence among Devadasis in northern Karnataka, India. Global Public Health. Advance online publication. doi:

- Li Y., Marshall C. M., Rees H. C., Nunez A., Ezeanolue E. E., Ehiri J. E. (2014). Intimate partner violence and HIV infection among women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of International AIDS Society, 17, 18845. doi:

- Mane P., Aggleton P. (2001). Gender and HIV/AIDS: What do men have to do with it? Current Sociology, 49(6), 23–37.

- McClarty L. M., Bhattacharjee P., Blanchard J. F., Lorway R. R., Ramanaik S., Mishra S., . . . Becker M. L. (2014). Circumstances, experiences and processes surrounding women’s entry into sex work in India. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 16, 149–163.

- Moses S., Ramesh B. M., Nagelkerke N. J., Khera A., Isac S., Bhattacharjee P., . . . Blanchard J. F. (2008). Impact of an intensive HIV prevention programme for female sex workers on HIV prevalence among antenatal clinic attenders in Karnataka state, south India: An ecological analysis. AIDS, 22(Suppl. 5), S101–S108.

- Murray L., Moreno L., Rosario S., Ellen J., Sweat M., Kerrigan D. (2007). The role of relationship intimacy in consistent condom use among female sex workers and their regular paying partners in the Dominican Republic. AIDS and Behavior, 11, 463–470.

- Orchard T. R. (2007a). Girl, woman, lover, mother: Towards a new understanding of child prostitution among young Devadasis in rural Karnataka, India. Social Science & Medicine, 64, 2379–2390.

- Orchard T. (2007b). In this life: The impact of gender and tradition on sexuality and relationships for Devadasi sex workers in rural India. Sexuality & Culture, 11, 3–27.

- Panchanadeswaran S., Johnson S. C., Sivaram S., Srikrishnan A. K., Latkin C., Bentley M. K., . . . Celentano D. (2008). Intimate partner violence is as important as client violence in increasing street-based female sex workers’ vulnerability to HIV in India. International Journal of Drug Policy, 19, 106–112.

- Pando M. A., Coloccini R. S., Reynaga E., Rodriguez Fermepin M., Gallo Vaulet L., Kochel T. J., . . . Avila M. M. (2013). Violence as a barrier for HIV prevention among female sex workers in Argentina. PLoS One, 8(1), e54147.

- Ramanaik S., Thompson L. H., du Plessis E., Pelto P., Annigeri V., Doddamane M., . . . Lorway R. (2014). Intimate relationships of Devadasi sex workers in South India: An exploration of risks of HIV/STI transmission. Global Public Health, 9, 1198–1210.

- Ramesh B. M., Moses S., Washington R., Isac S., Mohapatra B., Mahagaonkar S. B., . . . Blanchard J. F. (2008). Determinants of HIV prevalence among female sex workers in four south Indian states: Analysis of cross-sectional surveys in twenty-three districts. AIDS, 22(Suppl. 5), S35–S44.

- Schulkind J., Mbonye M., Watts C., Seeley J. (2016). The social context of gender-based violence, alcohol use and HIV risk among women involved in high-risk sexual behaviour and their intimate partners in Kampala, Uganda. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 18, 770–784.

- Shaw S., Pillai P. (2012). Understanding risk for HIV/STI transmission and acquisition within non-paying partnerships of female sex workers in southern India. Bangalore, India, Karnataka Health Promotion Trust.

- Syvertsen J. L., Robertson A. M., Rolon M. L., Palinkas L. A., Martinez G., Rangel M. G., Strathdee S. A. (2013). “Eyes that don’t see, heart that doesn’t feel”: Coping with sex work in intimate relationships and its implications for HIV/STI prevention. Social Science & Medicine, 87, 1–8.

- Travasso S. M., Mahapatra B., Saggurti N., Krishnan S. (2014). Non-paying partnerships and its association with HIV risk behavior, program exposure and service utilization among female sex workers in India. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 248. doi:

- Ulibarri M. D., Roesch S., Rangel M. G., Staines H., Amaro H., Strathdee S. A. (2015). “Amar te Duele” (“love hurts”): Sexual relationship power, intimate partner violence, depression symptoms and HIV risk among female sex workers who use drugs and their non-commercial, steady partners in Mexico. AIDS and Behavior, 19, 9–18.

- Ulibarri M. D., Strathdee S. A., Ulloa E. C., Lozada R., Fraga M. A., Magis-Rodriguez C., . . . Patterson T. L. (2011). Injection drug use as a mediator between client-perpetrated abuse and HIV status among female sex workers in two Mexico-US border cities. AIDS and Behavior, 15, 179–185.

- UNAIDS. (1999). Gender and HIV/AIDS: Taking stock of research and programmes. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

- Urada L. A., Morisky D. E., Hernandez L. I., Strathdee S. A. (2013). Social and structural factors associated with consistent condom use among female entertainment workers trading sex in the Philippines. AIDS and Behavior, 17, 523–535.

- Voeten H. A., Egesah O. B., Varkevisser C. M., Habbema J. D. (2007). Female sex workers and unsafe sex in urban and rural Nyanza, Kenya: Regular partners may contribute more to HIV transmission than clients. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 12, 174–182.

- Wong M. L., Lubek I., Dy B. C., Pen S., Kros S., Chhit M. (2003). Social and behavioural factors associated with condom use among direct sex workers in Siem Reap, Cambodia. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 79, 163–165.