Key messages

Alcohol consumption poses a significant public health challenge globally, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where the burden of alcohol-related harm is substantial. Despite this, the effectiveness of regulatory interventions in LMICs has been understudied, highlighting a gap addressed by this review.

Alcohol control policies, especially those targeting the physical availability and pricing of alcohol, have shown consistent effectiveness in reducing consumption and associated harms in LMICs. However, evidence on marketing restrictions remains scarce and inconclusive, while drink-driving interventions have demonstrated beneficial effects.

Strengthening the regular and statutory enforcement of alcohol control policies is likely to enhance their effectiveness, reducing alcohol-related harm in LMICs. Policymakers should prioritize interventions with robust evidence, such as pricing and availability restrictions, to achieve significant public health gains.

This review shows the importance of tailoring alcohol regulatory policies to the specific contexts of LMICs while addressing gaps in evidence, particularly regarding marketing restrictions. Investing in comprehensive, evidence-based strategies is important in mitigating the alcohol burden and improving population health in these regions.

Introduction

Alcohol is one of the most used recreational substances worldwide, and harmful consumption poses a significant public health challenge. In 2020, an estimated 2.3 billion people aged 15 years and above (47% of the global population) were drinkers (). Global per capita alcohol consumption rose from 5.5 l of pure alcohol in 2005 to 6.4 l in 2016. Around a quarter of all alcohol consumed globally is estimated to be unrecorded. Of recorded alcohol, 45% is consumed as spirits, 34% as beer, and 12% as wine ().

Alcohol consumption negatively affects individuals, their families, and society, contributing to 230 diseases and making it the fifth leading risk factor for global disease burden (). In 2016, harmful alcohol use accounted for 132.6 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) globally, with most of this burden occurring in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (). Among males aged 15–39 years, 66.3% of alcohol-related DALYs were due to injuries. Moreover, alcohol consumption was linked to 2.4 million global deaths (). The economic costs of harmful alcohol use include direct healthcare expenses, nonhealthcare costs, and productivity losses. The World Health Organization (WHO) has proposed a global strategy to reduce harmful alcohol use, recommending ‘Best Buys’ such as increased alcohol taxes, restrictions on marketing, and limiting the availability of alcohol (). Additional policies include drink-driving laws, minimum age restrictions, reducing retail outlet density, and labelling alcoholic beverages to inform consumers about the harms of alcohol ().

Many countries have implemented alcohol regulatory interventions, but their effectiveness is rarely evaluated. Research in high-income countries (HICs) has shown that Indigenous-led alcohol policies can improve health and social outcomes (). An umbrella review assessing the quality of systematic reviews evaluating the effectiveness of alcohol control interventions highlighted the absence of systematic reviews covering low-income or lower-middle-income countries (). This was corroborated in another systematic review aligned with WHO best practices in low-income and lower-middle-income countries between 1990 and 2015 (). A study examining noncommunicable disease (NCD) policies across 151 countries highlighted a lack of implementation of alcohol control policies ().

Industry self-regulation of alcohol marketing has proven ineffective, especially in protecting vulnerable populations. found widespread violations of self-regulated content guidelines and extensive youth exposure to alcohol marketing. Similarly, concluded that self-regulation fails to prevent alcohol advertising targeted at children and adolescents. More recently, identified that existing regulatory measures, including self-regulation, are inadequate in limiting youth exposure to digital alcohol advertising (; ; ). In addition, violations of the content guidelines within self-regulated alcohol marketing codes are highly prevalent and seldom penalized. In addition, as social media rapidly evolves, countries must adapt their regulatory frameworks to restrict and monitor digital alcohol advertising ().

Since 2000, per capita alcohol consumption has increased in many LMICs, including China and India, though trends vary across countries (). LMICs also have a higher proportion of unrecorded alcohol consumption (40%) compared with HICs (11%), and the health burden per litre of alcohol consumed is greater in LMICs (). Given the growing public health and economic burden in LMICs, context-specific policies based on robust evidence are urgently needed. A decade-old systematic review found a relationship between alcohol price or taxation and reduced consumption in LMICs (), but up-to-date evidence on the impact of other regulatory interventions is lacking. This systematic review aims to address this gap by examining the effectiveness of alcohol regulatory policies in LMICs, focusing on changes in alcohol consumption as well as health outcomes.

Materials and methods

This systematic review adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (). The review protocol is registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42023461005).

Criteria for eligibility

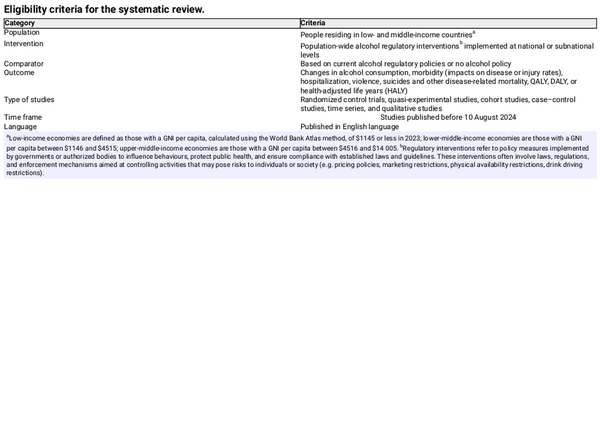

To be included in this review studies should have assessed the effectiveness of alcohol regulatory policies in LMICs, focusing on population-wide interventions and their impact on alcohol consumption and health outcomes. It considered randomized control trials, quasi-experimental studies, cohort studies, case–control studies, time-series studies, and qualitative studies published in English before 10 August 2024.

Table 1 depicts the eligibility criteria for the studies to be included into the systematic review.

All studies that fulfilled the above criteria were included. Systematic reviews, narrative reviews, letters to the editor, and articles lacking explicit information on methods were excluded.

Data sources and search strategy

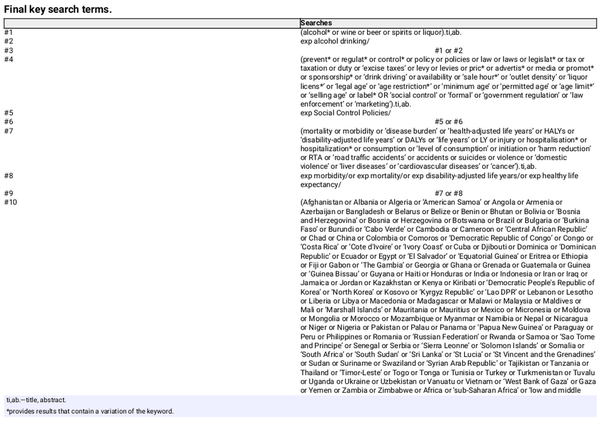

We conducted a systematic search across MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Web of Sciences., using terms related to alcohol consumption, health outcomes, and interventions. The final search was done on 10 August 2024. Details of the search strategy are provided in Supplementary file 1. We also searched grey literature using search terms such as ‘alcohol control policies’, ‘alcohol prevention’, including research organizations, government websites, and Google Scholar, and contacted corresponding authors when necessary. Additionally, reference lists of relevant books and articles were reviewed, including the third edition of the ‘Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity, Research and public policy’ () and its reference list. Table 2 provides the final key search terms.

Screening and data extraction

Two reviewers independently screened titles/abstracts, full texts, and extracted data using a predefined data extraction form. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus or a third reviewer. Extracted data included author, year, study setting, region, country income level (according to 2022 World Bank classification) (), study design, sample size, confounders, intervention domain (according to WHO ‘best buys’), specific intervention, time horizon for evaluation, reported outcome, key results, conclusion, and conflict of interest.

Quality assessment and appraisal

The reporting and methodological quality was independently assessed by two reviewers using four different tools for different study designs.

The quality of the cross-sectional studies was evaluated using the National Institutes of Health Quality Assessment Tool for cross-sectional studies and cohort studies (). This tool has 14 questions that investigate study objective, study design, sample size, confounders, and bias. We weighted each question on a scale of 1–5 according to the importance in measuring the quality of the study and gave marks for each response for the questions. Finally, total marks for all the questions for each study were converted to percentage. Studies with 0%–49%, 50%–74%, and ≥75% were graded as poor, intermediate, and good quality, respectively.

The quality of time-series studies was assessed using the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care standard criteria for assessing the risk of bias for ITS studies (). This tool has seven criteria. Criteria one, three, and four assess the threat of history, instrumentation, and testing, respectively. Criterion two assesses whether the ITS impact model was specified a priori, while criterion five assesses whether missing data were dealt with appropriately. Criterion six assesses whether all relevant outcomes that were part of the study objectives were reported. Lastly, criterion seven assesses whether data were analysed appropriately. Each criterion scored 1 if low risk and 0 otherwise. For each study, we created an aggregate score by combining scores across the seven criteria and subsequently categorized the aggregate score as poor quality (scores 0–2), intermediate quality (scores 3–5), and good quality (scores 6–7).

Modelled studies included in the review were assessed for quality using the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research—Society for Medical Decision-Making Modelling Good Research Practices Task Force Checklist (ISPOR-SMDM) (). The checklist has five criteria evaluating the model structure, data sources, model validation, uncertainty and sensitivity analysis, and generalizability and reproducibility of the model. Each criterion score from 0 to 2, if details are poor or absent scored 0, partial or moderate scored 1, and comprehensive or good quality scored 2. For each study, we created an aggregate score by combining scores across the five criteria and subsequently categorized the aggregate score as poor quality (scores 0–3), intermediate quality (scores 4–7), and good quality (scores 8–10).

The quality of qualitative study was evaluated using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Checklist: For Qualitative Research (). This checklist consists of 10 questions covering three sections covering the validity of results, results itself, and local applicability of results. Each of the 10 checklist items scored as 2 points for ‘Yes’ (fully met), 1 point for ‘Can’t Tell’ (partially met), and 0 points for ‘No’ (not met or unclear), resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 20. Studies scoring 15–20 points were categorized as good quality, scores of 8–14 points intermediate quality, and scores of 0–7 points poor quality.

The quality assessment was for overall study level and not the outcomes for included studies. Discrepancies in quality assessment were resolved by consensus.

More details regarding the quality assessment tools and the process of risk of bias assessment are given in Supplementary file 2.

Data management and synthesis

All the studies were uploaded to EndNote V.21 to remove duplicates. The remaining studies were uploaded into Covidence, which is a web-based programme that assists collaboration between reviewers through the screening and selection process (). Additional duplicates were identified in Covidence and removed. All data extracted from the included studies were entered to Microsoft Excel 2013 spreadsheets. Studies were stratified by intervention category and outcome based on the WHO ‘best buys’ (). Studies examining multiple interventions were discussed separately. The results were grouped into changes in alcohol consumption, health outcomes, and other outcomes. Alcohol-related outcomes were reported using the terms as they appear in the original studies. Some of these terms may not reflect current preferred language, but these terms were kept as it is to report the original findings accurately.

Results

Results of study selection

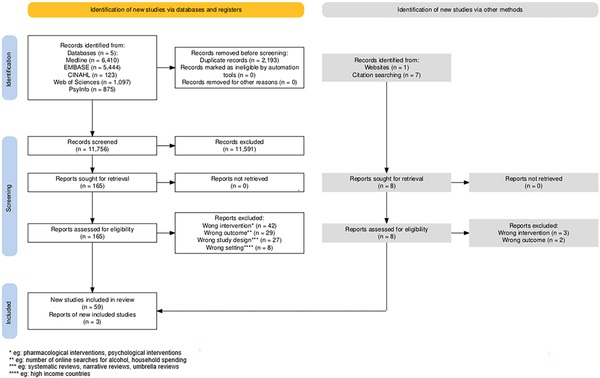

The databases search yielded 13 949 entries, and eight additional studies were obtained from the reference list of prior reviews, websites, and books, giving a total of 13 957 studies. After removing duplicates, 11 756 studies remained. Screening titles and abstracts led to 173 full-text reviews, with 62 studies meeting inclusion criteria. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process at each step ().

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram.

Study characteristics

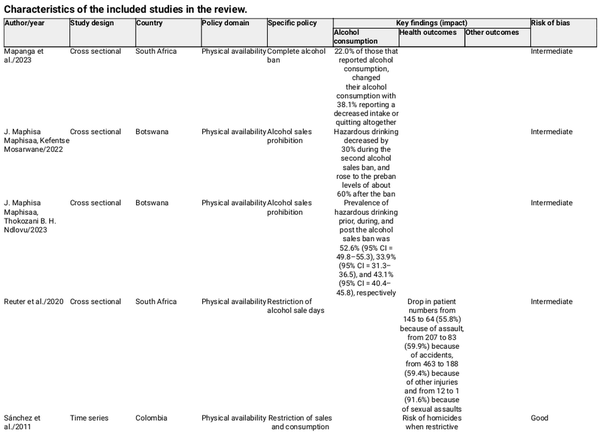

All 62 studies were published after 2004, with 57 (92%) focusing on single countries and five (8%) being multicountry studies. Most were from Asia (n = 24, 39%), followed by South America (n = 17, 27%), Africa (n = 11, 18%), Europe (n = 2, 3%), and North America (n = 2, 3%). Six studies (10%) spanned multiple continents. The majority (n = 48, 77%) were conducted in upper-middle-income countries, while seven were from lower-middle-income countries. Cross-sectional designs predominated (n = 32, 52%), followed by time-series (n = 22, 35%), modelling (n = 7, 11%), and qualitative (n = 1, 2%) studies. Table 3 provides detailed study characteristics.

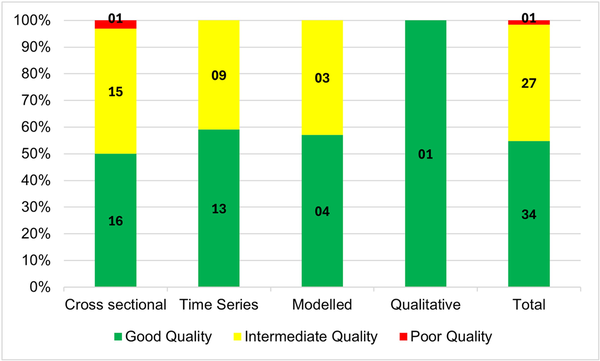

Over half (55%) were of good quality, 43% were of moderate quality, and one (2%) was of poor quality. Figure 2 provides a comprehensive overview of the quality assessment of studies by study design, as well as the overall quality of the studies included in the systematic review.

Figure 2

Risk of bias for all studies by the study design.

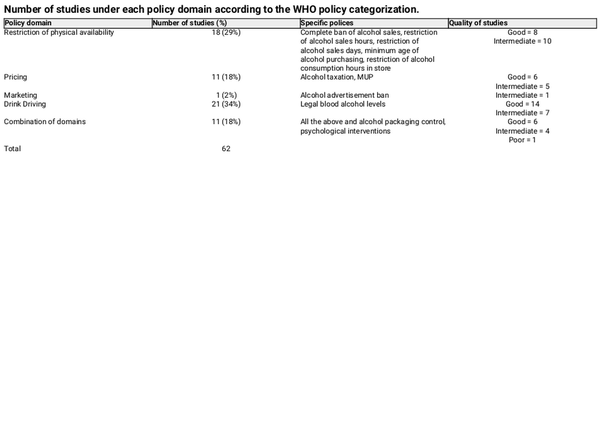

Overview of alcohol policy domains and outcomes

Overall, 21 studies focused on interventions aimed at restricting drink driving, while 11 studies assessed a combination of interventions across all the policy domains. Table 4 provides a summary of the studies by WHO alcohol policy domain with specific policies and quality of studies under each domain.

In terms of outcomes, 31 studies (47%) focused on health outcomes, 26 (39%) on changes in alcohol consumption, and nine on other outcomes, namely number of heavy drinkers returning late from the liquor outlets, odds of a driver having a positive breathalyser result, and frequency of adults who drove after abusive alcohol consumption.

Effectiveness of alcohol policies

Restriction of physical availability of alcohol

Eighteen studies evaluated interventions that restricted the physical availability of alcohol.

Alcohol consumption-related outcomes

Two studies evaluated the impact of a national alcohol sales ban on hazardous drinking in Botswana, 2020–2021. The first, conducted from August to September 2020, found a reduction in hazardous drinking from 91.7% before the ban to 62.3% during, rebounding to 90.4% postban (). The second, from June to September 2021, reported a decrease from 52.6% preban to 33.9% during, rising to 43.1% postban (). In South Africa, 38.1% of current drinkers reduced or quit alcohol during the COVID-19 lockdown sales ban from March 2020 to October 2021 (). Subramanian et al. found no difference in alcohol consumption between Indian states with varying ban levels (). In Thailand, raising the legal purchase age for alcohol had no effect on consumption among high-risk youth (), as underage individuals continued buying alcohol in areas with lax enforcement (). In Zacatecas, Mexico, a law mandating a 2 a.m. bar closing and 10 p.m. off-premises alcohol cut-off saw noncompliance in 27% of bars and 53% of stores, but breath testing revealed a 30% reduction in blood alcohol concentration and heavy drinking late at night, along with fewer physical fights and drunk customers during festive periods ().

Health outcomes

Two studies in South Africa found that complete or partial bans of alcohol sales during the COVID-19 lockdown reduced assaults, accidents, injuries, and sexual assaults at a rural hospital and reduced trauma cases by 59%–69% (, ). In Cali, Colombia, stricter alcohol sales and consumption hours regulations and prohibition of sales to minors led to reductions in homicides and unintentional injuries, with greater enforcement showing stronger effects (). In Sao Paulo, Brazil, mandatory night closures of bars and restaurants in 2001–2004 resulted in a 10% drop in homicides and car accidents (). A similar policy in Diadema, Brazil, 2002, led to a reduction in homicides and assaults against women (). Short-term alcohol bans during Brazil’s 2012 elections decreased road traffic accidents by 19%, traffic injuries by 43%, and related hospitalizations by 17% (). However, banning alcohol consumption at gas stations in Porto Alegre showed no significant change in blood alcohol levels (). In South India, banning liquor shops near highways had no significant effect on head injuries or alcohol-related accidents (). Enforcing minimum age restrictions in Mexico led to a 16.4% reduction in acute alcohol intoxication among youth ().

Other outcomes

In Mexico, restricting liquor outlet hours reduced the number of late-night returnees who had been heavily drinking, potentially lowering injuries, homicides, and road accidents (). In Uganda, a national ban on sachet alcohol led to a 26% decrease in overall alcohol availability and a 50% reduction in sachet alcohol availability ().

Pricing of alcohol

For this policy domain, eight studies focused on alcohol taxation and three on minimum unit price (MUP) of alcohol.

Alcohol consumption-related outcomes

In India, price increases reduced consumption of beer, spirits, and country liquor, with elasticities ranging from −0.14 to −0.46 (). A Thai study found a 10% increase in alcohol taxes reduced lifetime drinking among youth by 4.3% (). In South Africa, increasing the MUP of alcohol by ZAR (South African Rand) 3.00 per drink lowered consumption by 11.9% among heavy-drinking households (). A Chinese study found that tax increase in year 2001 led to an immediate consumption drop, while tax relaxation in year 2006 caused a significant rise in consumption (). In Thailand, alcohol tax hikes in 2005, 2007, and 2009 reduced per capita alcohol consumption by 0.07, 0.06, and 0.05 l per 30 days, respectively (). In Vietnam, beer and wine consumption was found to be price and expenditure inelastic, with small declines in consumption for price increases ().

Three modelled studies predicted the alcohol consumption-related outcomes of taxation and MUP interventions. A study in Lebanon estimated that a 20% targeted tax on high-ethanol alcoholic beverages would reduce alcohol intake by 15.7%, compared with 5.3% with a broad 20% tax. Among binge drinkers, targeted taxes reduced consumption by 16.3%, while broad taxes risked increasing it by 3.3% (). Another study in Lebanon predicted that a targeted MUP reduced ethanol consumption by 0.23 l per month among university students, while a flat MUP reduced it by 0.1 l (). In South Africa, a modelled evaluation showed a Rand10 MUP increase would reduce consumption by 4.4%, with the largest impact on heavy drinkers ().

Health outcomes

In Kazakhstan, between 2007 and 2013, alcohol sales declined due to price increase, leading to a 47% drop in cardiovascular disease mortality and reductions in accidents and trauma-related deaths (). A Chinese study found that alcohol tax increases reduced alcohol use disorders (AUD) and DALYs, while tax reduction increased both (). In Thailand, a 24.7% tax hike was linked to a sustained reduction of 0.38 road traffic fatalities per 100 000 people every 30 days ().

Two modelled studies predicted the health outcomes of taxation and MUP interventions. A study in Kazakhstan estimated that a 20%, 50%, and 100% alcohol tax increase could prevent 0.7%, 1.76%, and 3.57% of alcohol-attributable cancers and 0.1%, 0.26%, and 0.53% of all cancers (). In South Africa, a R10 MUP could prevent 20 585 deaths and avert 900 332 alcohol-related cases over 20 years ().

Marketing control of alcohol

Only one study, rated as having intermediate quality, evaluated the effectiveness of restrictions on alcohol marketing alone. This multilevel cross-sectional study used the Indian Human Development survey data for 2005 and 2012. After controlling for confounders, the authors found no association between watching TV, listening to the radio and reading newspapers containing alcohol marketing, and alcohol consumption ().

Restrictions on drink driving

Overall, 21 studies evaluated the effectiveness of interventions to restrict drink driving. The main interventions included implementing a legal cut-off for blood alcohol levels for driving or having checkpoints for random and selective breath testing.

Health outcomes

In Serbia, lowering the legal blood alcohol limit led to an initial drop in drink driving fatalities, but deaths resurged the following year, with no sustained reduction in alcohol-related driving incidents (). In Cuba, sobriety checkpoints led to a 29.9% reduction in accidents, a 70.8% decrease in deaths, and a 58.7% drop in injuries (). In Turkey, an alcohol-related traffic law resulted in a 14% decrease in traffic fatality rates and 1519 fewer deaths over 6 years ().

In Brazil, five studies evaluated drink driving laws enacted in 2008 and 2012. The 2012 law significantly reduced fatal traffic accidents and hospitalizations (; ), while the 2008 law showed no significant reduction in traffic-related mortality (). A study in the capital city reported a 1.8% drop in traffic injuries and a 7.2% decrease in fatalities after the 2008 law’s enhancement (). Another study concluded that ‘dry laws’ reduced overall and pedestrian mortality, though motorcyclist and vehicle occupant fatalities remained stable from 1980 to 2014 ().

In China, four studies analysed the impact of the 2011 drunk driving law. One study reported a modest reduction in traffic mortality and injuries in the postintervention period (), while another found a 9.6% decrease in road injuries but a 38.8% increase in alcoholism cases and 3.6% increase in nontraffic injuries (). Another study showed a decrease in age-standardized mortality from 2005 to 2015 (). Wang et al. found a 6.8% reduction in drink driving fatalities after the law’s implementation (Zhaoxin ).

In Mexico, two studies assessed the impact of drunk driving laws. One found a significant reduction in monthly traffic deaths and a 23.2% decrease in the fatality rate postintervention (). Another confirmed a decline in alcohol-related deaths after stricter laws were enacted ().

A modelled study in Thailand predicted that selective and random breath testing, combined with mass media campaigns, could reduce alcohol-related road accidents by 15% and 14%, respectively (). Another modelled Thai study estimated a quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gain of 0.43 years for male and 0.1 years for female binge drinkers through random breath testing and media campaigns ().

Other outcomes

The zero-tolerance law for blood alcohol levels in Brazil, 2008, led to positive breathalyser results among drivers dropping by 45% (). Over 2007 to 2013, there was a 45% reduction in adults driving after heavy drinking, with significant declines immediately following the implementation of drink driving laws (). Three Brazilian capital cities saw reductions in driving under the influence by 0.65%, 1%, and 1.4% after the zero-tolerance law, while two showed no significant change (). In Turkey, drivers subject to higher BAC limits had a significantly higher risk of nonfatal accidents (). In Botswana, stricter penalties from the 2008 Road Traffic Act contributed to a 22% reduction in crash rates between 2009 and 2012 ().

Combined/multiple interventions

Eight studies evaluated the effectiveness of combined/multiple interventions to reduce the harmful effects of alcohol. The interventions included the restriction of physical availability, pricing, marketing, drink driving, alcohol labelling, and psychological interventions.

Alcohol consumption related outcomes

Ramsoomar et al. examined South Africa’s alcohol control interventions (1998–2008) including advertising bans, sales restrictions, control packaging, and increased taxation and found no change in lifetime alcohol use or age of initiation, with 12% of adolescents starting alcohol use before age 13 years. Binge drinking among females rose from 27% to 36%, and drink driving increased (). A cross-sectional study in five countries found that stricter alcohol policies correlated with higher lifetime abstinence, with advertising bans having the strongest effect (). A 15-country study found that restrictions on alcohol availability and minimum legal drinking age were consistently linked to lower consumption, high alcohol prices, greater restriction to advertising reduces the consumption, while random breath testing had no effect (). In 46 African countries, stricter policies correlated with lower per capita alcohol consumption (). In Southeast Asia, higher taxes and effective tax methods led to lower consumption, while per capita alcohol consumption was higher in countries with fewer alcohol control policies (). A study in Thailand, South Africa, Peru, Mongolia, and Vietnam estimated that a one-unit increase in the ‘International Alcohol Control Policy Index’, which is a score derived from the combination of alcohol control interventions was associated with a 13.9% reduction in drinking frequency and a 16.5% reduction in drinking volume (). Another study in Thailand reported that a one-unit increase in the policy score was associated with a 1.98% reduction in alcohol consumption (). Eight years after Thailand raised the minimum purchasing age and enforced sales bans, male intoxication dropped by 40% but female binge drinking rose ().

Health outcomes

Grigoriev et al. studied alcohol control policies in Belarus (1980–2013) and found that while the significant decline in adult male mortality could not be fully attributed to these policies, they likely contributed ().

A modelled study in Thailand predicted that alcohol taxation had the greatest impact in reducing NCD deaths, followed by psychological intervention, and availability restrictions. Advertisement bans had the lowest impact. When combined, these interventions could prevent over 13 000 NCD deaths among men and about 5000 among women (). Another modelling study in Thailand, South Africa, Peru, and Vietnam showed that lower alcohol prices, later purchasing times, and liking for ads predicted higher consumption ().

Discussion

Evidence on alcohol control interventions in LMICs is expanding, with studies highlighting their effectiveness in reducing alcohol-related harm. Most of the available studies on alcohol control interventions in LMICs are from Asia, which may reflect not only research priorities but also where such interventions are more commonly implemented. The limited number of studies in other regions may, in part, be due to fewer policy interventions being introduced, highlighting both a research gap and an implementation gap. Published studies examining policies restricting the physical availability of alcohol outnumbered the other alcohol control interventions. Alcohol consumption was the most frequently reported outcome. Interventions related to pricing and taxation had the most consistent effect in reducing alcohol consumption and improving health outcomes.

Restriction of physical availability of alcohol

Our review found that restrictions on the physical availability of alcohol were mostly effective in reducing alcohol-related harm. This contrasts with the findings from a systematic review of studies from HICs. In that review, Bryden et al. assessed outlet density, distance to nearest outlet, willingness to sell alcohol to minors, and local changes to licensing regulations and found inconclusive results regarding their effectiveness in reducing alcohol consumption. Most studies included in their review were rated as medium or weak quality, while studies in our review were of good to intermediate quality (). However, the tools used for quality assessments differed between the two studies. A review investigating the public health impact of the minimum legal drinking age in the USA had similar findings to our review, with this intervention resulting in reduced alcohol-related crashes and consumption among youth (). Another review focused on studies primarily from HICs found that policies regulating alcohol trading hours and days could reduce injuries, alcohol-related hospitalizations, homicides, and crime ().

Pricing of alcohol

Across all studies, alcohol taxation and pricing policies were effective in reducing alcohol consumption. Greater effects were observed with increasing taxation and MUPs. Our findings are similar to those of who found that found price-based alcohol policies such as MUP are likely to reduce alcohol consumption and alcohol-related morbidity and mortality. However, evidence from HICs has shown mixed results. found that alcohol tax interventions had selective impacts on subpopulations, drinking patterns, and harms (). Another review reported that increased alcohol taxes or prices are unlikely to be effective in reducing binge drinking, regardless of gender or age group, as binge drinkers are not highly responsive to price increases (). A systematic review conducted by ) on elasticity of alcohol consumption in LMICs reported an inverse relationship between price and alcohol consumption. All the above findings in HICs are similar to the findings in LMICs in the current systematic review.

Marketing control of alcohol

This review showed mixed findings on alcohol advertisement bans. A cross-sectional study of intermediate quality found no significant impact on alcohol consumption (). However, several studies evaluating multiple alcohol interventions reported positive outcomes for alcohol advertisements bans. A systematic review that assessed the effectiveness of alcohol advertising and protective messages on alcohol use reported inconclusive findings, while stating that there was some indication that greater exposure to advertising may be associated with higher alcohol use (). This is supported by a systematic review of experimental studies which found that alcohol advertisements may increase the consumption of alcoholic beverages immediately after exposure (). Similarly, another systematic review concluded that exposure to digital alcohol marketing is associated with increased alcohol consumption and increased binge or hazardous drinking behaviour (). Another systematic review reported that the evidence in HICs was insufficient to conclude that total or partial alcohol marketing bans reduce alcohol consumption ().

Restrictions on drink driving

This review found that drink driving policies were effective in reducing alcohol-related health harms and the number of drivers under the influence of alcohol. However, continual enforcement is needed to retain effectiveness. Other systematic reviews have found similar results. In a review of studies conducted in China, showed that enforcing blood alcohol concentration limits had greater beneficial outcomes when combined with other interventions such as educational campaigns and penalty systems. Similarly, found that regular breathalyser tests, penalties, and roadside inspections were effective in changing driver behaviour, especially in relation to speeding and alcohol consumption while driving. A review of studies mostly from the USA concluded that there was limited but consistent evidence that strengthening laws for penalties related to alcohol consumption or speeding was associated with a reduced risk of injury ().

Combined/multiple interventions

Eight studies evaluated the effects of combined or multiple alcohol control interventions. These included modelling studies and studies looking at the correlation between alcohol intake and the ‘International Alcohol Control policy index’. All studies showed that combinations of policies were effective in reducing alcohol consumption and related health outcomes except for one study. This cross-sectional, intermediate quality study in South Africa found that interventions did not reduce binge drinking among young females, but it also reported that gaps in implementation and enforcement levels could lead to this outcome. Countries with a greater number of interventions, and more stringent and restrictive policies, had lower alcohol harms ().

The effectiveness of alcohol control policies is not solely determined by their design but also by the degree to which they are enforced and complied with. Key issues include inconsistent enforcement, limited institutional capacity, and socioeconomic and political constraints. Studies reveal that even well-designed policies may fail to achieve their intended impact due to weak regulatory mechanisms, lack of resources for monitoring and compliance, and corruption within enforcement agencies (). Moreover, street-level bureaucrats, such as law enforcement officers and local government officials, play a crucial role in policy execution, yet their discretion in enforcement and potential resistance to policy changes can lead to uneven implementation (). Additionally, the influence of powerful industry stakeholders can lead to policy dilution, delaying or obstructing stricter regulations (). These implementation challenges contribute to variability in policy effectiveness. The rise of unregulated alcohol markets also presents challenges to the effectiveness of alcohol control policies, as seen in cases where increased taxation and MUP have unintentionally driven consumers towards illicit alcohol. In Turkey, high alcohol taxes have increased bootleg alcohol production, resulting in fatal poisonings (). Therefore, alcohol control policies must incorporate measures such as strengthened enforcement, consumer education, and alternative harm reduction strategies to prevent the displacement of consumption into illicit markets.

The COVID-19 pandemic had an impact on alcohol policy effectiveness, with varied approaches across countries leading to mixed outcomes. A systematic review reported that some nations banned alcohol sales, resulting in increased alcohol withdrawal cases, methanol toxicity, and suicides, while others declared alcohol ‘essential,’ leading to higher home consumption and related issues. The pandemic also shifted drinking patterns, with reports of increased binge and solitary drinking, particularly among vulnerable groups like those with pre-existing AUD or mental health conditions (). However, it is important to acknowledge that the effects of alcohol bans were not uniformly negative. In South Africa, one study found that 38.1% of current drinkers reported reducing or quitting alcohol during the lockdown-related sales ban (). Additionally, two other South African studies documented positive public health outcomes, including significant reductions in accidents, injuries, assaults, and sexual assaults in a rural hospital, as well as a 59%–69% decrease in trauma-related admissions during the lockdown period (, ).

Incorporating cultural and religious contexts is important when evaluating the effectiveness of alcohol regulatory policies in LMICs. In many LMICs with significant Muslim populations, alcohol consumption is legally restricted and culturally discouraged due to religious beliefs (). For instance, in countries like Pakistan and Indonesia, Islamic teachings and legal frameworks impose strict limitations on alcohol availability and use (). These cultural and religious norms can significantly influence the outcomes of alcohol control policies, potentially enhancing their effectiveness due to societal reinforcement of abstinence. However, such restrictions may also lead to unintended consequences, such as the proliferation of unregulated alcohol markets, which pose additional public health challenges ().

This review provides an overview of the current evidence on population-level interventions addressing alcohol consumption and related harm in LMICs. The findings can assist policymakers and public health practitioners in selecting effective policy options. While evidence on the effectiveness of alcohol advertising bans remains mixed, interventions in other policy areas have demonstrated effectiveness. However, LMICs may face practical and political challenges in implementing these interventions due to resource constraints and competing priorities (). Key challenges include political pressure from the alcohol industry, which opposes or weakens control measures through lobbying, campaign contributions, and industry-funded research (). Alcohol control is often deprioritized by governments in LMICs, given the need to address pressing issues such as infectious diseases, poverty, and malnutrition (). Political instability and leadership changes also pose a threat to the consistent implementation of these policies, as shifting agendas can disrupt policy continuity ().

Taxation and pricing policies are particularly effective. LMIC governments might prioritize these fiscal measures as they offer dual benefits: reducing alcohol consumption and related harms while generating revenue. The savings from reduced alcohol-related burdens and the revenue generated from such policies could be reinvested in further alcohol interventions, NCD control, or other sectors.

Since the impact of interventions is often context-dependent, public health practitioners and researchers should evaluate their applicability to their local settings.

This systematic review has several strengths and limitations. First, limiting our search to English language articles may have excluded relevant studies in other languages. However, we employed a detailed and comprehensive search strategy, accessing multiple databases and grey literature, which should have minimized the risk of missing eligible studies. Second, we did not pool the results due to significant heterogeneity in the interventions, methodologies, and outcomes. However, given that the majority of studies were conducted in upper-middle-income countries and many utilized observational designs, the generalizability of these findings to low-income countries and the establishment of causal relationships remains uncertain. Thus, findings should be interpreted with caution.

Despite these limitations, this review addresses an important gap in the evidence on the effectiveness of alcohol control interventions in LMICs and highlights understudied policy areas, particularly in low-income countries. Sixty per cent of the studies were of good quality and 38% of intermediate quality, providing a reasonable level of confidence in our findings.

Conclusion

This systematic review offers a comprehensive overview of the effectiveness of alcohol control interventions in LMICs. Most studies focused on interventions restricting alcohol availability, which were largely effective. Pricing and taxation policies consistently showed strong evidence of success, while other policy areas also had positive effects, except for marketing interventions where the evidence was scant. The evidence indicates that regular, statutory enforcement enhances intervention effectiveness. LMIC governments should implement strong alcohol control policies and invest in research capacity to measure their impact, accounting for social, economic, and political factors to tailor policies to local contexts. Bridging the gap between research and policy is crucial for informed resource allocation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the librarians at Griffith University, Gold Coast Campus, Queensland, Australia.

References

- Abreu DROM, Souza EM, Mathias TAF. Impact of the Brazilian traffic code and the law against drinking and driving on mortality from motor vehicle accidents. Cad Saude Publica 2018;34:e00122117. 10.1590/0102-311X00122117

- Aguilera SL, Sripad P, Lunnen JC, et al Alcohol consumption among drivers in Curitiba, Brazil. Traffic Inj Prev 2015;16:219–24. 10.1080/15389588.2014.935939

- Allen LN, Nicholson BD, Yeung BYT, et al Implementation of non-communicable disease policies: a geopolitical analysis of 151 countries. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:50–8. 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30446-2

- Allen LN, Pullar J, Wickramasinghe KK, et al Evaluation of research on interventions aligned to WHO ‘Best Buys’ for NCDs in low-income and lower-middle income countries: a systematic review from 1990 to 2015. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000535. 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000535

- Andreuccetti G, Carvalho HB, Cherpitel CJ, et al “Reducing the legal blood alcohol concentration limit for driving in developing countries: a time for change? Results and implications derived from a time-series analysis (2001-10) conducted in Brazil”: erratum.YR—2012. Addiction 2012;107:236. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03753.x

- Araujo M, Illanes E, Chapman E, et al Effectiveness of interventions to prevent motorcycle injuries: systematic review of the literature. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot 2016;24:406–22. 10.1080/17457300.2016.1224901.

- Assanangkornchai S, Saingam D, Jitpiboon W, et al Comparison of drinking prevalence among Thai youth before and after implementation of the alcoholic beverage control act. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2020;46:325–32. 10.1080/00952990.2019.1692213

- Babor TF, Casswell S, Graham K, et al Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity Research and Public Policy, 3rd edn. New York: Oxford University Press, 2023.

- Biderman C, de Mello JMP, Schneider A. Dry law and homicides: evidence from the São Paulo metropolitan area. Econ J Royal Econ Soc 2010;120:157–82. 10.1111/j.1468-0297.2009.02299.x

- Boniface S, Scannell JW, Marlow S. Evidence for the effectiveness of minimum pricing of alcohol: a systematic review and assessment using the Bradford Hill criteria for causality. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013497. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013497

- Bryden A, Roberts B, McKee M, et al A systematic review of the influence on alcohol use of community level availability and marketing of alcohol. Health Place 2012;18:349–57. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.11.003

- Buse K, Mays N, Walt G. Making Health Policy, 2nd edn. England: Open University Press, 2012.

- Campos VR, de Souza e Silva R, Duailibi S, et al The effect of the new traffic law on drinking and driving in São Paulo, Brazil. Accid Anal Prev 2013;50:622–7. 10.1016/j.aap.2012.06.011

- Caro JJ, Briggs AH, Siebert U, et al Modeling good research practices–overview: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM modeling good research practices task force-1. Value Health 2012;15:796–803. 10.1016/j.jval.2012.06.012

- Casswell S, Huckle T, Parker K, et al Effective alcohol policies are associated with reduced consumption among demographic groups who drink heavily. Alcohol Clin Exp Res (Hoboken) 2023;47:786–95. 10.1111/acer.15030

- Casswell S, Huckle T, Wall M, et al Policy-relevant behaviours predict heavier drinking and mediate the relationship with age, gender and education status: analysis from the international alcohol control study. Drug Alcohol Rev 2018;37:S86–95. 10.1111/dar.12669

- Chaaban J, Haddad J, Ghandour L, et al Impact of minimum unit pricing on youth alcohol consumption: insights from Lebanon. Health Policy Plan 2022;37:760–70. 10.1093/heapol/czac021

- Chaiyasong S, Gao J, Bundhamcharoen K. Estimated impacts of alcohol control policies on NCD premature deaths in Thailand. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:9623. 10.3390/ijerph19159623

- Chalak A, Ghandour L, Anouti S, et al The impact of broad-based vs targeted taxation on youth alcohol consumption in Lebanon. Health Policy Plan 2020;35:625–34. 10.1093/heapol/czaa018

- Chelwa G, Toan PN, Hien NTT, et al Do beer and wine respond to price and tax changes in Vietnam? Evidence from the Vietnam household living standards survey. BMJ Open 2019;9:e027076. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027076

- Chu KM, Marco J-L, Owolabi EO, et al Trauma trends during COVID-19 alcohol prohibition at a South African regional hospital. Drug Alcohol Rev 2022;41:13–9. 10.1111/dar.13310

- Colchero M, Guerrero-Lopez C, Quiroz-Reyes J, et al Did “conduce sin alcohol” a program that monitors breath alcohol concentration limits for driving in Mexico city have an effect on traffic-related deaths? Prev Sci 2020;21:979–84. 10.1007/s11121-020-01133-3

- Cook WK, Bond J, Greenfield TK. Are alcohol policies associated with alcohol consumption in low- and middle-income countries? Addiction 2015;109:1081–90. 10.1111/add.12571

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP qualitative research checklist. CASP. 2018. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (20 February 2025, date last accessed).

- Davletov K, Berkinbaev S, Ibragimova F, et al The effects of alcohol and tobacco price increases on premature CVD mortality in Kazakhstan in 2007-2013. Eur Heart J 2016;37:1133. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv531

- De Boni R, Leukefeld C, Pechansky F. Young people's blood alcohol concentration and the alcohol consumption city law, Brazil. Rev Saude Publica 2008;42:1101–4. 10.1590/S0034-89102008000600018

- DeJong W, Blanchette J. Case closed: research evidence on the positive public health impact of the age 21 minimum legal drinking age in the United States. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl 2014;75:108–15. 10.15288/jsads.2014.75.108

- Ditsuwan V, Lennert Veerman J, Bertram M, et al Cost-effectiveness of interventions for reducing road traffic injuries related to driving under the influence of alcohol. Value Health 2013;16:23–30. 10.1016/j.jval.2012.08.2209

- Duailibi S, Ponicki W, Grube J, et al The effect of restricting opening hours on alcohol-related violence. Am J Public Health 2007;97:2276–80. 10.2105/AJPH.2006.092684

- Fei G, Li X, Sun Q, et al Effectiveness of implementing the criminal administrative punishment law of drunk driving in China: an interrupted time series analysis, 2004-2017. Accid Anal Prev 2020;144:105670. 10.1016/j.aap.2020.105670

- Ferreira-Borges C, Esser MB, Dias S, et al Alcohol control policies in 46 African countries: opportunities for improvement. Alcohol Alcohol 2015;50:470–6. 10.1093/alcalc/agv036

- GBD 2020 Alcohol Collaborators. Population-level risks of alcohol consumption by amount, geography, age, sex, and year: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2020. Lancet 2022;400:185–235. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00847-9

- Gibbs N, Angus C, Dixon S, et al Effects of minimum unit pricing for alcohol in South Africa across different drinker groups and wealth quintiles: a modelling study. BMJ Open 2021;11:e052879. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052879

- Gómez-García L, Pérez-Núñez R, Hidalgo-Solórzano E. Short-term impact of changes in drinking-and-driving legislation in Guadalajara and Zapopan, Jalisco, Mexico. Cad Saude Publica 2014;30:1281–92. 10.1590/0102-311x00121813

- Grigoriev P, Andreev EM. The huge reduction in adult male mortality in Belarus and Russia: is it attributable to anti-alcohol measures? PLoS One 2015;10:e0138021. 10.1371/journal.pone.0138021

- Guanche Garcell H, Suárez Enríquez T, Gutiérrez García F, et al Impact of a drink-driving detection program to prevent traffic accidents (Villa Clara province, Cuba). Gac Sanit 2008;22:344–7. 10.1157/13125356

- Guimarães AG, da Silva AR. Impact of regulations to control alcohol consumption by drivers: an assessment of reduction in fatal traffic accident numbers in the federal district, Brazil. Accid Anal Prev 2019;127:110–7. 10.1016/j.aap.2019.01.017

- Guimarães RA, de Morais Neto OL, Dos Santos TMB, et al Impact of the program life in traffic and new zero-tolerance drinking and driving law on the prevalence of driving after alcohol abuse in Brazilian capitals: an interrupted time series analysis. PLoS One 2023;18:e0288288. 10.1371/journal.pone.0288288

- Haddaway NR, Page MJ, Pritchard CC, et al PRISMA2020: an R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and open synthesis. Campbell Syst Rev 2022;18:e1230. 10.1002/cl2.1230

- Hategeka C, Ruton H, Karamouzian M, et al Use of interrupted time series methods in the evaluation of health system quality improvement interventions: a methodological systematic review. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e003567. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003567

- Hernández-Llanes NF, Pérez-Pérez E, Lozano Morales V, et al Effect of monitoring the compliance of banning alcohol sales to minors in the volume of underage acute alcohol intoxication cases in Mexico: a controlled ITSA analysis. Int J Ment Health Addict 2020;18:347–57. 10.1007/s11469-019-00161-7

- Hu A, Zhao X, Room R, et al The effects of alcohol tax policies on alcohol consumption and alcohol use disorders in Mainland of China: an interrupted time series analysis from 1961–2019. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2023;49:746–55. 10.1080/00952990.2023.2280948

- Ilhan MN, Yapar D. Alcohol consumption and alcohol policy. Turk J Med Sci 2020;50:1197–202. 10.3906/sag-2002-237

- Jankhotkaew J, Casswell S, Huckle T, et al Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of effective alcohol control policies: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:6742. 10.3390/ijerph19116742

- Jankhotkaew J, Casswell S, Huckle T, et al A composite index of provincial alcohol control policy implementation capacity in Thailand. Int J Drug Policy 2024;130:104504. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2024.104504

- Joseph J, Roshan R, Sudhakar G, et al Did the supreme court liquor shop ban in 2017 on highways impact the incidence and severity of road traffic accidents. Curr Med Issues 2020;18:165–9. 10.4103/cmi.cmi_20_20

- Karakus A, İdiz N, Dalgiç M, et al Comparison of the effects of two legal blood alcohol limits: the presence of alcohol in traffic accidents according to category of driver in Izmir, Turkey. Traffic Inj Prev 2015;16:440–2. 10.1080/15389588.2014.968777

- Kumar S. Price elasticity of alcohol demand in India. Alcohol Alcohol 2017;52:390–5. 10.1093/alcalc/agx001

- Leung JYY, Au Yeung SL, Lam TH, et al What lessons does the COVID-19 pandemic hold for global alcohol policy? BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e006875. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006875

- Leung J, Casswell S, Parker K, et al Effective alcohol policies and lifetime abstinence: an analysis of the international alcohol control policy index. Drug Alcohol Rev 2023;42:704–13. 10.1111/dar.13582

- Li Q, Babor TF, Zeigler D, et al Health promotion interventions and policies addressing excessive alcohol use: a systematic review of national and global evidence as a guide to health-care reform in China. Addiction 2014;110:68–78. 10.1111/add.12784

- Limaye RJ, Srirojn B, Lilleston P, et al A qualitative exploration of the effects of increasing the minimum purchase age of alcohol in Thailand. Drug Alcohol Rev 2013;32:100–5. 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00486.x

- Macdonald M, Martin Misener R, Weeks L, et al Covidence vs excel for the title and abstract review stage of a systematic review. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2016;14:200–1. 10.1097/01.XEB.0000511346.12446.f2

- Malta DC, Berna RT, Silva MM, et al Consumption of alcoholic beverages, driving vehicles, a balance of dry law, Brazil 2007-2013. Rev Saude Publica 2014;48:692–966. 10.1590/s0034-8910.2014048005633

- Manthey J, Jacobsen B, Klinger S, et al Restricting alcohol marketing to reduce alcohol consumption: a systematic review of the empirical evidence for one of the ‘best buys’. Addiction 2024;119:799–811. 10.1111/add.16411

- Mapanga W, Craig A, Mtintsilana A, et al The effects of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns on alcohol consumption and tobacco smoking behaviour in South Africa: a national survey. Eur Addict Res 2023;29:127–40. 10.1159/000528484

- Maphisa JM, Mosarwane K. Changes in retrospectively recalled alcohol use pre, during and post alcohol sales prohibition during COVID pandemic in Botswana. Int J Drug Policy 2022;102:103590. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103590

- Maphisa Maphisa J, Ndlovu TBH. Changes in hazardous drinking pre, during and post 70-day alcohol sales ban during COVID-19 pandemic in Botswana. Int J Drug Policy 2023;114:103992. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2023.103992

- McCormack C. Turkey issues bootleg alcohol warning after more than 100 people are fatally poisoned in tourist hotspots. NEW YORK POST. 2025. https://nypost.com/2025/02/11/world-news/turkey-issues-fake-alcohol-warning-after-more-than-100-people-are-fatally-poisoned-in-tourist-hotspots/ (26 February 2025, date last accessed).

- Michalak L, Trocki K. Alcohol and Islam: an overview. Contemp Drug Probl 2006;33:523–62. 10.1177/009145090603300401

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535. 10.1136/bmj.b2535

- Muhunthan J, Angell B, Hackett ML, et al Global systematic review of indigenous community-led legal interventions to control alcohol. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013932. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013932

- Nakaguma MY, Restrepo BJ. Restricting access to alcohol and public health: evidence from electoral dry laws in Brazil. Health Econ 2018;27:141–56. 10.1002/hec.3519

- National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Quality assessment tool for observational, cohort and cross sectional studies. NHLBI. 2021. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (28 February 2025, date last accessed).

- Nazif-Munoz JI, Anakök GA, Joseph J, et al A new alcohol-related traffic law, a further reduction in traffic fatalities? Analyzing the case of Turkey. J Safety Res 2022;83:195–203. 10.1016/j.jsr.2022.08.015

- Nelson JP. Binge drinking and alcohol prices: a systematic review of age-related results from econometric studies, natural experiments and field studies. Health Econ Rev 2015;5:6. 10.1186/s13561-014-0040-4

- Nelson JP, McNall AD. What happens to drinking when alcohol policy changes? A review of five natural experiments for alcohol taxes, prices, and availability. Eur J Health Econ 2017;18:417–34. 10.1007/s10198-016-0795-0

- Noel JK, Babor TF, Robaina K. Industry self-regulation of alcohol marketing: a systematic review of content and exposure research. Addiction 2017;112:28–50. 10.1111/add.13410

- Noel JK, Sammartino CJ, Rosenthal SR. Exposure to digital alcohol marketing and alcohol use: a systematic review. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2020;19:57–67. 10.15288/jsads.2020.s19.57

- Paschall MJ, Miller TR, Grube JW, et al Compliance with a law to reduce alcoholic beverage sales and service in Zacatecas, Mexico. Int J Drug Policy 2021;97:103352. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103352

- Radoš Krnel S, Levičnik G, van Dalen W, et al Effectiveness of regulatory policies on online/digital/internet-mediated alcohol marketing: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2023;13:115–28. 10.1007/s44197-023-00088-2

- Ramsoomar L, Morojele NK. Trends in alcohol prevalence, age of initiation and association with alcohol-related harm among South African youth: implications for policy. S Afr Med J 2012;102:609. 10.7196/SAMJ.5766

- Rashmi R, Paul R, Srivastava S. Association of mass media exposure and alcohol consumption apropos alcohol-advertisement ban in India: multilevel analysis of panel data. J Subst Use 2022;28:379–88. 10.1080/14659891.2022.2051617

- Reuter H, Jenkins LS, De Jong M, et al Prohibiting alcohol sales during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has positive effects on health services in South Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2020;12:e1–4. 10.4102/phcfm.v12i1.2528

- Rovira P, Kilian C, Neufeld M, et al Fewer cancer cases in 4 countries of the WHO European region in 2018 through increased alcohol excise taxation: a modelling study. Eur Addict Res 2021;27:189–97. 10.1159/000511899

- Sanchez-Ramirez DC, Voaklander D. The impact of policies regulating alcohol trading hours and days on specific alcohol-related harms: a systematic review. Inj Prev 2018;24:94–100. 10.1136/injuryprev-2016-042285

- Sánchez AI, Villaveces A, Krafty RT, et al Policies for alcohol restriction and their association with interpersonal violence: a time-series analysis of homicides in Cali, Colombia. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:1037–46. 10.1093/ije/dyr051

- Sebego M, Naumann RB, Rudd RA, et al The impact of alcohol and road traffic policies on crash rates in Botswana, 2004-2011: a time-series analysis. Accid Anal Prev 2014;70:33–9. 10.1016/j.aap.2014.02.017

- Sherman SG, Srirojn B, Patel SA, et al Alcohol consumption among high-risk Thai youth after raising the legal drinking age. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;132:290–4. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.023

- Siegfried N, Parry C. Do alcohol control policies work? An umbrella review and quality assessment of systematic reviews of alcohol control interventions (2006-2017). PLoS One 2019;14:e0214865. 10.1371/journal.pone.0214865

- Smart M, Mendoza H, Mutebi A, et al Impact of the sachet alcohol ban on alcohol availability in Uganda. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2021;82:511–5. 10.15288/jsad.2021.82.511

- Sornpaisarn B, Shield K, Cohen J, et al Elasticity of alcohol consumption, alcohol-related harms, and drinking initiation in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Alcohol Drug Res 2013;2:45–58. 10.7895/ijadr.v2i1.50

- Sornpaisarn B, Shield KD, Cohen JE, et al Can pricing deter adolescents and young adults from starting to drink: an analysis of the effect of alcohol taxation on drinking initiation among Thai adolescents and young adults. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2015;5:S45–57. 10.1016/j.jegh.2015.05.004

- Sornpaisarn B, Shield KD, Cohen JE, et al The association between taxation increases and changes in alcohol consumption and traffic fatalities in Thailand. J Public Health (Oxf) 2016;38:e480–8. 10.1093/pubmed/fdv163

- Sornpaisarn B, Shield K, Manthey J, et al Alcohol consumption and attributable harm in middle-income south-east Asian countries: epidemiology and policy options. Int J Drug Policy 2020;83:102856. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102856

- Souza CRL, Russo LX, da Silva EN. Association of the new zero-tolerance drinking and driving law with hospitalization rate due to road traffic injuries in Brazil. Sci Rep 2022;12:5447. 10.1038/s41598-022-09300-y

- Stautz K, Brown KG, King SE, et al Immediate effects of alcohol marketing communications and media portrayals on consumption and cognition: a systematic review and meta-analysis of experimental studies. BMC Public Health 2016;16:465. 10.1186/s12889-016-3116-8

- Subramanian SV, Nandy S, Irving M, et al Role of socioeconomic markers and state prohibition policy in predicting alcohol consumption among men and women in India: a multilevel statistical analysis. Bull World Health Organ 2005;83:829–36. Epub 2005 Nov 10.

- Van Walbeek C, Chelwa G. The case for minimum unit prices on alcohol in South Africa. S Afr Med J 2021;111:680–4. 10.7196/SAMJ.2021.v111i7.15430

- Vendrame A, Pinsky I. Inefficacy of self-regulation of alcohol advertisements: a systematic review of the literature. Braz J Psychiatry 2011;33:196–202. 10.1590/S1516-44462011005000017

- Vichitkunakorn P, Khampang R, Leelahavarong P, et al Cost-utility analysis of an alcohol policy in Thailand: a case study of a random breath testing intervention. BMC Health Serv Res 2024;24:739. 10.1186/s12913-024-11189-4

- Voas RB, Romano E, Kelley-Baker T, et al A partial ban on sales to reduce high-risk drinking south of the border: seven years later. J Stud Alcohol 2006;67:746–53. 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.746

- Volpe FM, Ladeira RM, Fantoni R. Evaluating the Brazilian zero tolerance drinking and driving law: time series analyses of traffic-related mortality in three major cities. Traffic Inj Prev 2017;18:337–43. 10.1080/15389588.2016.1214869

- Walker L, Gilson L. We are bitter but we are satisfied': nurses as street-level bureaucrats in South Africa. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:1251–61. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.020

- Walls H, Cook S, Matzopoulos R, et al Advancing alcohol research in low-income and middle-income countries: a global alcohol environment framework. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e001958. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001958

- Walls H, Johnston D, Matita M, et al The politics of agricultural policy and nutrition: a case study of Malawi’s farm input subsidy programme (FISP). PLoS Glob Public Health 2023;3:e0002410. 10.1371/journal.pgph.0002410

- Wang Z, Zhang Y, Zhou P, et al The underestimated drink driving situation and the effects of zero tolerance laws in China. Traffic Inj Prev 2014;16:429–34. 10.1080/15389588.2014.951719

- World Bank. New World Bank country classifications by income level. World Bank. 2022. https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/new-world-bank-country-classifications-income-level-2022-2023 (10 August 2024, date last accessed).

- World Health Organization. ‘Best buys’ and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. World Health Organization. 2017. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/259232/WHO-NMH-NVI-17.9-eng.pdf?sequence= (10 August 2024, date last accessed).

- World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. World Health Organization. 2018. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/274603/9789241565639-eng.pdf? (10 August 2024, date last accessed).

- World Health Organization. Global Alcohol Action plan (2022–2030). 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240090101.

- Xiao W, Ning P, Schwebel DC, et al Evaluating the effectiveness of implementing a more severe drunk-driving law in China: findings from two open access data sources. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:832. 10.3390/ijerph14080832

- Zhao A, Chen R, Qi Y, et al Evaluating the impact of criminalizing drunk driving on road-traffic injuries in Guangzhou, China: a time-series study. J Epidemiol 2016;26:433–9. 10.2188/jea.JE20140103

- Zivković V, Nikolić S, Lukić V, et al The effects of a new traffic safety law in the Republic of Serbia on driving under the influence of alcohol. Accid Anal Prev 2013;53:161–5. 10.1016/j.aap.2013.01.012