Key messages

Healthcare networks represent a viable approach to integrate care between hospitals and primary care. The institutionalization of healthcare networks requires robust leadership, effective coordination, appropriate resource mobilization and healthcare staff pooling.

Implementing healthcare networks often requires a balance between top-down policies, including a general legal policy framework institutionalizing a comprehensive healthcare reform, and bottom-up initiatives combining adaptive leadership, community participation and transformative learning processes.

Lack of interoperable health information systems and insufficient relational coordination among professionals impede effective collaboration within healthcare networks.

We found that organizational learning and relational collaboration among healthcare organizations are crucial in establishing enduring, dynamic inter-organizational partnerships.

Introduction

Nowadays, health systems confront increasingly complex wicked challenges such as global health pandemics (e.g. COVID-19), demographic and epidemiological transitions, budgetary constraints and fragmented health service delivery (). Yet, health systems require strong care integration and efficient collaboration between healthcare institutions, health workers and communities (; ; ).

However, in most instances, healthcare reforms are implemented using hierarchical top-down planning, which lacks organizational resilience to adapt to ‘wicked’ health challenges (; ). By wicked challenges, we mean health issues characterized by non-linearity (i.e. emergence and feedback and feedforward loops) and interdependency that increases the need for cross-boundary coordination (). Addressing these challenges requires new flexible forms of governance that extend beyond the scope of individual healthcare organizations ().

In many countries, addressing complex, wicked challenges, the rising cost of care, care fragmentation and inequitable access to care have urged the territorial grouping of public hospitals and other healthcare providers. Over the past two decades, new models of healthcare collaboration have been developed in high-income countries, such as area hospital networks (e.g. ‘Groupement Hospitalier de Territoire’ in France) and accountable care organizations in the USA. Evidence suggests that healthcare networks (HN) can facilitate inter-organizational collaboration and efficient referral systems and strengthen public–private partnerships in healthcare (; ; ; ).

HN were designed to improve inter-organizational cooperation, operational efficiency and resource mutualization (e.g. centralization of information systems, purchasing and human resources) (, ). Here, we define the inter-organizational performance (i.e. partnership effectiveness) as the combination of capabilities and resources to produce changes in healthcare programmes, improvement of healthcare utilization, responsiveness, costs of health services, satisfaction of stakeholders and improvement of population health indicators (; ).

Yet, mixed evidence has been reported on the effect of HN on financial performance, cost containment and overall inter-organizational performance. For instance, some scholars found that less-integrated networks and complex hospital networks are associated with negative operating margins with no short-term economic benefit (; ; ; ; ). Others found no relationship between the governance of HN and overall inter-organizational performance (; ).

HN are decentralized governance structures designed to improve inter-organizational collaboration, enable local adaptation of national health policies, promote the integration of healthcare services and prioritize patient-centred care (; ; ). HN can consist of various combinations of facilities, including hospitals, primary healthcare facilities and other types of healthcare facilities (social and community care, emergency care, etc). Despite undeniable benefits, the implementation of HN can be challenging (e.g. lack of clinical integration, fragmented decision-making, poor strategic alignment among network partners, increased staff workload and resistance to change) (, ). These stem from various degrees of strategic responses of healthcare organizations to government pressure and institutional mandates (). This highlights the importance of studying the different characteristics of healthcare networks, the underlying policy processes and drivers of change, and the underlying collaborative dynamics for effective collaboration and contextual conditions that enable or hinder overall inter-organizational performance, improved population health management, and quality and access to care.

Despite the growing academic and practitioner interest in HN, there is still a lack of evidence about the enablers and facilitators of inter-organizational collaboration within HN in the field of Health Policy and System Research (; ). Hence, the question of fostering inter-organizational collaboration in HN remains unanswered (; ; ).

To address this knowledge gap, this scoping review aimed to synthesize evidence about the underlying collaborative processes and contextual enablers and facilitators of effective inter-organizational collaboration within HN. The review will attempt to fill the policy gaps expressed by key stakeholders during a workshop organized in March 2022 at the Mohammed VI University of Health and Sciences (UM6SS), highlighting the lack of clarity on the most appropriate configuration of HN that will best fit the Moroccan context and what enablers and barriers to take into consideration during the actual implementation of area HN. This scoping review will provide some lessons learnt for policy makers to address the persistent divide between health policy processes and the actual healthcare service provision, weak autonomy of public hospitals and poor collaboration between different healthcare facilities at local levels (; ; ; ; ).

The results of the review will inform a workshop with policymakers and researchers at the Knowledge for Health Policies at UM6SS to support future decision-making concerning the implementation of area HN in Morocco.

Material and methods

We followed the methodological guidance for scoping reviews developed by and later adapted by . We adopted the following steps: (1) consultation with key stakeholders, (2) formulation of the review question, (3) identification of relevant studies, (4) study selection, (5) data charting, and (6) collation and summary of findings and reporting of results. The scoping review approach proved appropriate in reviewing a broad and heterogeneous body of evidence (; ).

The collaborative governance framework

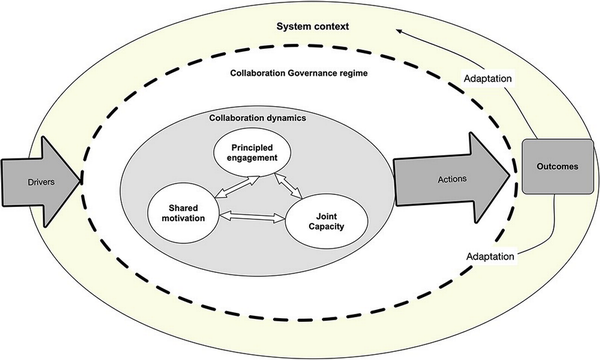

Following guidance from the literature (; ), we used a framework analysis to guide the different steps of this scoping review. We used ‘the integrative collaborative governance regime (CGR) model’ developed by (see Figure 1). It is considered a cross-disciplinary framework applied in different disciplines, such as in public administration (; ), in healthcare () and in low- and middle-income countries (; ). The CGR model allows for a systemic understanding of collaborative dynamics and provides a commonly used framework applicable in the comparative empirical analysis of inter-organizational collaboration processes, internal dynamics causal pathways and performance ().

Figure 1

Collaborative governance dynamics as defined by

CGRs serve as mechanisms for cross-boundary collaboration and governmental processes that bring together multiple stakeholders in consensus-based decision making (; ). These regimes encompass collaborative dynamics, which involves principled engagement, shared motivation and the capacity for joint action that enable concrete collective actions leading to organizational outcomes and adaptive changes (see Figure 1). ‘Principled engagement’ refers to long-term interactions between stakeholders across administrative boundaries. ‘Shared motivation’ encompasses internal legitimacy, mutual trust and commitment among actors. The ‘capacity for joint action’ involves the requisite means for collaboration, including procedures, institutional arrangements, leadership, knowledge and resources (; ).

‘Collaborative dynamics’ are shaped by the general system context, encompassing contextual drivers of change embedded in a healthcare systems’ political, economic, environmental and social contexts. These drivers include leadership, external crises, health system reforms, the context of uncertainty and interdependence (see Figure 1).

Consultation with stakeholders

We developed our review questions in response to a priority-setting exercise during a stakeholder workshop on 17 March 2022. This workshop involved stakeholders from the Ministry of Health and Social Protection, central and regional health officers, representatives from national health observatories, and representatives from the World Health Organization office and other research and policy centres, The Alliance for Health Policy and System Research, and other ministerial departments at the Knowledge for Policy Centre at the UM6SS, Casablanca.

During the workshop, we used an inductive process using post its and flip charts to categorize key topics expressed by stakeholders. Among the topics identified, stakeholders emphasized a lack of consensus among policymakers on the nature, type and implementation processes of HN within the actual healthcare reforms in Morocco. We then finalized our review question as follows: What are the different typologies of healthcare networks, and what are key enablers and barriers that might facilitate or hinder the implementation of the area healthcare networks? More specifically, we focused on patterns of social processes and mechanisms that facilitate or hinder efficient coordination between healthcare facilities within HN.

This scoping review aims to reflect on the lessons learnt from other international experiences and provide policy recommendations to inform the ongoing reforms of area HN [or Groupement Sanitaire de Territoire (GST)] institutionalized by a legal framework in 2021 by the Ministry of Health and Social Protection ().

Specifying the review question

Following several meetings with the research team, we further refined our review question as follows. (1) What are the characteristics of inter-organizational collaboration within the context of HN? (2) phe contextual conditions within which these processes are enabled or hindered?(3)

What are the key lessons learnt to improve inter-organizational collaboration within HN? To what extent do these lessons learned fit the North African and Middle East context?

Identification of relevant studies

We searched four databases (PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar and Scopus). We identified additional sources through manual searching, citation tracking and snowballing from reference lists. We framed our search strategy using the phenomenon of interest–concept–context (PCC) framework (). (1) Phenomenon of interest: ‘hospital networks’ or ‘hospital grouping’ or ‘accountable care organisations’, (2) concept: inter-organisational collaboration, (3) context: healthcare.

We used the following search strategy in PubMed: (‘inter-organisational collaboration’ OR ‘relational collaboration’ OR ‘collaborative governance’ OR ‘Inter-organisational coordination’ OR ‘Institutional Collaboration’ OR ‘organisational collaboration’) AND (‘Strategic alliances’ OR ‘Cooperative arrangements’ OR ‘Collaborative agreements’ OR ‘networks’ OR ‘grouping’ OR ‘Mergers’ OR ‘Partnership’ OR ‘Alliances’ OR ‘Groups’) AND (‘healthcare’ OR ‘Health’ OR ‘hospitals’ OR ‘accountable care organisations’) (other search strategies are given in supplementary Appendix 1, see online supplementary material).

Study selection

We included peer-reviewed papers published between 2012 and 2022 that specifically addressed in the title or the abstract the notion of collaborative governance or inter-organizational collaboration within HN. We excluded protocols, reviews, commentaries, conference proceedings and book reviews. Additionally, we excluded papers focused on clinical collaboration and HN that do not include hospitals and studies outside the healthcare sector. We used the Rayyan software () to manage the title and abstract selection.

Charting the data and synthesis of results

Data charting was informed by the CGR framework (). The CGR framework is based on the integration of empirical research data from various settings in public management (; ) and in healthcare (, ). We selected Emerson’s CGR framework for its broad applicability in different disciplines, particularly in healthcare (). We adopted the CGR to explore cross-boundary governance systems and inter-sectoral collaboration at national, regional and local levels, including in low- and middle-income countries (, ). CGR was selected for its wide application in cross-disciplinary research, including in public administration (; ), management, health policy and system research (; ; ), both in high- and in low- and middle-income counties (, ; ).

We used thematic analysis () to guide data charting while being sensitive to emerging themes. In practice, we used Emerson’s a priori framework to guide the initial deductive coding of key collaborative governance processes. We used a data charting grid using Excel software (see supplementary Appendix 2 in the online supplementary material) that comprised three parts. (1) General description of included studies (author, date, publication country origin, participants to the network, study objectives, study type and design, definitions of collaborative governance, barriers and facilitators, study limitations); (2) collaborative governance framework themes [general system context, drivers of change, collaborative dynamics (principled engagement, shared motivation, capacity for joint actions)]; and (3) outputs and outcomes (, ).

We were also sensitive to emergent themes. We inductively coded processes facilitating or hindering the collaborative dynamics within HN.

Results

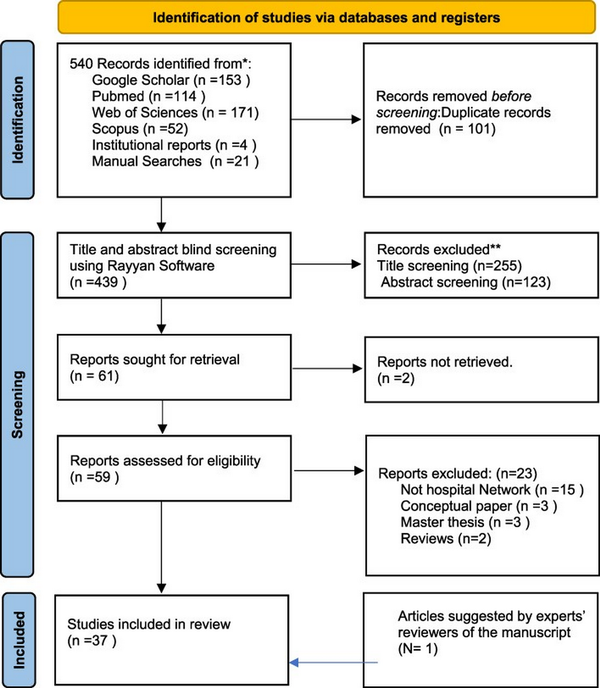

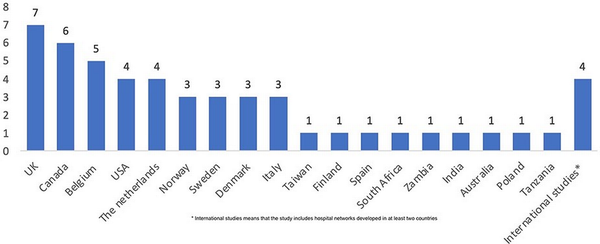

We included a total of 539 papers after removing 100 duplicates. After title, abstract and full-text screening, only 37 articles fit our inclusion criteria (see Figure 2). We found that most studies of hospital networks were reported in the USA, Canada and Belgium. Few studies were reported in Sub-Saharan Africa. None were published from the Middle East and North African region (Figure 3).

Figure 2

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram

Figure 3

Geographical distribution of included studies

Most studies (24 out of 37) used qualitative designs and multiple data collection, including interviews, focus group discussions, participant observation and document analysis (see Appendix 1 table 1). Seven studies used mixed methods designs. Only six studies used quantitative design. Some authors used innovative research approaches such as the realist evaluation (), ethnography (), social network analysis (n=2) (), health policy analysis (n = 3) or participatory action research (n=2) (see supplementary Appendix 3 in the online supplementary material). All included studies relied on retrospective data, except for and who adopted a longitudinal design.

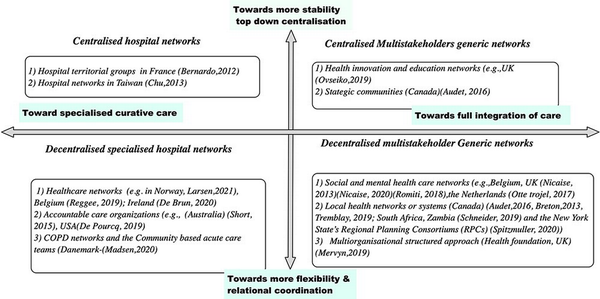

Typology of HN

There is a variety of HN. These can be classified according to a structural perspective depending on the type of partner organizations [exclusively formed by hospitals or combining hospitals with primary, social, community care and other educational services (labelled multi-stakeholder HN)] (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

The typology of healthcare networks

Hospital networks are strategic alliances of public hospitals in the same public health regions. Examples are ‘hospital territorial groups’ in France (), accountable care organizations in the USA () and hospital networks in Spain (). Other integrated HN included, besides hospitals, different types of healthcare providers such as primary care and social care facilities in Canada (), Italy (), Portugal (), The Netherlands (; ) and in the USA (). Many multidisciplinary networks were organized according to the scope of services provision around specific high-priority health programmes (traumatology, mental health) (), palliative care, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and oncology networks in Quebec (; ) and in Poland () and maternal neonatal care in Tanzania ().

We also found that HN can be classified as centralized vs decentralized. In some countries, the HN was institutionalized by legal frameworks and implemented in a hierarchical top-down fashion in the context of comprehensive healthcare reforms. For instance, in the UK, the Health and Social Act of 2012 triggered the reorganization of health providers into clinical commissioning groups led by general practitioners and the creation of a national foundation trust, an autonomous grouping of National Health Service health providers including teaching hospitals over which the Department of Health has no control ().

In contrast, decentralized HN are characterized by the lack of centralized governing bodies, which promote relational coordination within loosely coupled networks of primary healthcare facilities. In countries such as Belgium and the USA, the network formation followed a decentralized policy implementation and bottom-up decision-making processes with the participation of various stakeholders at local levels (health facilities managers and providers, social services and community actors). One example are Healthcare Innovation Education Clusters in the UK, where members belong to various institutions (National Health Service providers, general practitioner practices, higher education institutions, local government, charities and industries) ().

In Canada, the 2015 healthcare care network reforms set the agenda for the reorganization of primary HN, the formation of strategic communities and the creation of the Quebec Cancer Network (; , ; ; ). In Portugal, the merger of primary HN with social care facilities has facilitated the integration of health systems through the creation of the Mission Unit for Integrated Continuing Care ()

Decentralized HN are considered to be flexible organizational forms which favour full integration between health and social services, and improve relational coordination between various stakeholders and resilience to address wicked health challenges, such as the coordination of cancer and mental health clinical pathways (, , ). HN here can be considered complex adaptive social systems that favour better knowledge sharing, efficient mutualization of resources, staff pooling and cross-boundary institutional capacity building ().

In summary, top-down, centralized health care may be more suitable for highly specialized hospitals. In contrast, bottom-up complex adaptive networks are better suited for health networks combining primary care with secondary hospital care in multiple heterogeneous geographical areas.

The collaborative governance regime

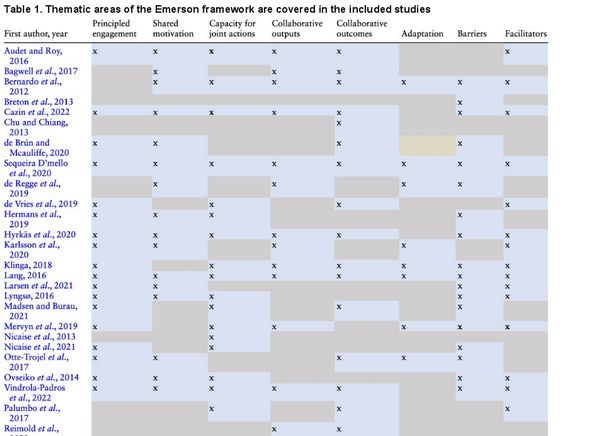

In this section, we report themes identified according to the framework described by . Additional emergent themes were identified using thematic analysis (see Table 1). Our scoping review showed that most of the studies reported empirical evidence on the importance of principled engagement (27 out of 37), shared motivation (24 out of 37) and capacity for joint actions (20 out of 37). These factors were considered crucial in leveraging internal collaborative dynamics within HN. However, few studies addressed adaptive and systemic changes (11 out of 37) and collaborative outputs (16 out of 37). Most studies focused on barriers (5 out of 37) rather than facilitators (18 out of 37).

The general system context

Our scoping review showed that the formation of HN is often influenced by contextual factors that motivate the prospect of a new collaborative governance regime. The general system context refers to the challenges and opportunities that influenced the formation of HN. These include social, economic and political conditions such as political dynamics and power relations within communities. The general system context that triggered the formation of centralized health networks was hallmarked by top-down hierarchical reforms where the stewardship role of the governing entities is considered a crucial factor in the coordination between various health providers. For instance, showed that, in managing regional outbreaks in The Netherlands, regional public health agencies and hospitals played key stewardship roles in coordinating the outbreak response. In these settings, HN were considered policy instruments to promote system changes in the governance of health systems and to foster collaboration beyond healthcare organizational boundaries, which may lead to organizational innovations ().

In addition, our scoping review showed that the formation of HN was also influenced by the failure of pre-existing traditional structures to address complex inter-organizational coordination [e.g. mental and social care networks in Belgium and the UK (; )], the unsatisfactory performance of traditional healthcare systems, the inefficiency of informal referral systems, the fragmentation of care, limited connectedness between health providers () and lack of mutualization of resources (; ).

In this context, the role of legal policy frameworks was considered a critical contextual factor that laid the foundation for inter-organizational collaborations within HN in high-income (; ; ; ) and low-income (e.g. Zambia, South Africa, India) () countries.

Collaborative dynamics

According to Emerson, collaborative dynamics refer to the drivers that energize participation to overcome the cost of initial network formation and set the dynamic of inter-organizational collaboration. As described in Table 1, most included studies referred to Emerson’s collaborative dynamics drivers (principled engagement, shared motivation and capacities for joint actions) (; ; ).

Principled engagement

Our study has shown that the collaborative dynamics within HN are triggered by the principled engagement of actors, their internal legitimacy, and the underlying dynamics of social interactions based on shared motivation, mutual trust and shared understanding (; ). Shared commitment reinforces synergy among partners who develop a strong sense of ownership and long-term alliance during all project phases (). Scholars highlighted the importance of maintaining a trustworthy climate and internal legitimacy, which facilitates the adoption of quality improvement healthcare initiatives (; ) and fosters long-term sustainable inter-organizational collaboration ().

Shared motivation

At the early formation stage of the health networks, most included studies referred to the importance of principled engagement (i.e. mutual commitment) in explaining the willingness of HN actors to share healthcare information (; ; ; ) and to actively participate in the collective decision making processes (steering committees) (; ; ; )(). For instance, in The Netherlands, Belgium and Canada, participatory governing bodies named ‘strategic communities’ allowed the creation of enabling conditions for participatory decision-making and improved mutual understanding and principled engagement of HN members ().

Capacity for joint actions

Leadership

The capacity for joint actions depends on the stewardship of internal governing bodies (strategic and steering committees). These governing bodies formulate, implement and evaluate new area healthcare strategies to better adapt to population needs (). These governing bodies effectively built contractual agreements and long-term strategic alliances and implemented joint collaborative actions such as pooling strategies to tackle human resource shortages (; ).

Our scoping review showed the importance of adaptive systemic leadership that combines formal leadership roles of central authorities with emergent distributed leadership that mobilizes operational frontline leadership (; ). Scholars of included studies argued that adaptive leadership is necessary to create a holding environment that supports patient-centred care, resource exchange, peer learning and equitable power distribution (). Leadership and governance enable equitable resource marshalling (), promote shared goals () and strengthen the actors’ sense of belonging. This is done through participatory decision-making and co-creation of knowledge () and continuous adaptation of operational procedures (; ).

Scholars asserted that leadership increases shared motivation and fosters mutual commitment and collaborative dynamics over time (; ; ).

Knowledge and power-sharing

Collaborative leadership creates a holding environment and collaborative spaces and facilitates resource and information exchange (; ; ; ; ). Strong leadership is critical in framing the architecture of power dynamics, institutionalizing governing bodies and promoting a culture of collaboration instead of competition within the HN (; ; ; ; ).

Scholars such as ( and ) referred to the importance of relational coordination, particularly in HN, comprising shared goals, shared knowledge, and effective communication to alleviate the cultural and professional differences and power differentials between healthcare entities. Additionally, relational and learning dynamics are considered critical enablers for fostering the utilization of information and communication technologies, reducing staff resistance to change and enabling the implementation of organizational innovation such as telemedicine in HN (; ). Reducing change resistance relies on promoting relational coordination based on accurate and timely communication oriented towards problem solving and a blame-free culture. Relation coordination facilitates the co-production of culturally sensitive knowledge about critical issues in healthcare systems (; )

Resources

Developing managerial and leadership capacities is needed to ensure efficient resource allocation and appropriate standardization of rules and procedures (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ). This will foster shared responsibility of health facility managers and their commitment. Trained healthcare managers effectively provide appropriate follow-up mentorship, benchmarking and coaching, and instil a sense of competition between HN members (e.g. the Kangaroo mother care competition to reward high-quality facilities) ().

Other scholars emphasized the importance of the mutualization of resources within HN (e.g. pooling of human resources and marshalling of equipment and supplies between network members). For instance, in Tanzania, the Comprehensive Community-Based Rehabilitation provided facilities such as starter packs of essential medicines, equipment such as vacuum extractors and suction machines, supplies for neonatal care and the rehabilitation of existing infrastructure using local government funds ().

Finally, promoting leadership development programmes for HN managers will reinforce the capacity of joint action by fostering collaborative and distributed leadership practices (; ; ; ; ).

Procedural and institutional arrangements

Most scholars emphasized the importance of institutionalizing procedural arrangements, allowing the smooth functioning of HN. Formalization of inter-organizational collaboration refers to the standardization of roles and responsibilities and the design of the network organizational structure and organogram (i.e. strategic steering committees and governing boards) (; ), and developing guidelines, rules and procedures (; ). For instance, the Comprehensive Community Based Rehabilitation (i.e. a maternal and neonatal HN including 22 public hospitals) in Tanzania focused on developing a memorandum of agreement, an annual letter of agreement and standard operating procedures, that helped to clarify the roles and functions of network members (health professionals) and facilitated referral systems and timely communication ().

In short, the appropriate mix of leadership capabilities, resources and governance procedural arrangements are vital factors that foster HN capacities of joint actions by providing a supportive and coherent policy environment (e.g. legal instruments, shared mandates and operational management procedures) (; ; ; ). This includes defining the roles and responsibilities of partners and partnership procedural arrangements (; ; ).

Our scoping review showed that effective collaborative dynamics within a HN depends on the appropriate mix between soft leadership capabilities with formal operational management and procedural arrangements (). Many scholars emphasized the crucial role played by soft skills, including interpersonal and intrapersonal relationships, knowledge exchange and trust relationship, in maintaining effective and sustainable collaboration (; ; ; ; ).

Outputs of collaborative actions

Inter-organizational collaboration has proven to be beneficial in the development of joint strategic plans and the successful implementation of planned joint actions within HN (; ; ; ). Moreover, it has also proved appropriate in facilitating the development of strategic healthcare alliances and the expansion of networks to include other types of health facilities (; ; ; ). In practical terms, HN resulted in the increased managerial overall performance of healthcare systems and smooth implementation of cross-organizational quality assurance projects (). HN were considered an effective form of healthcare decentralization (; ).

The implementation of shared collaborative governance has contributed to the efficiency and competitiveness of partner organizations (), strengthened interprofessional relationships, and improved the well-being of health professionals and managers (; ; ; ). HN may have facilitated shared collaborative governance and promoted improved long-term outcomes, including staff commitment (; ), shared responsibility and decision-making (, ), trust relationships (), and long-term ownership and commitment ().

Collaborative outcomes

Perceived impact.

Only eight studies have specifically examined the impact of HN on health outcomes. These studies have focused on various aspects, such as access to care (; ; ), quality of care (; ; ; ) [e.g. improved maternal and neonatal health ()] and patient satisfaction (; ). Limited indications suggest that HN might improve financial performance, risk sharing, cost containment efficiency and responsiveness to patients’ needs (; ).

Our scoping review showed that the implementation of shared internal rules of procedures facilitated inter-organizational shared communication channels (; ), reduced hospital readmission rates, congestion in tertiary hospitals () and unplanned hospital admissions for patients with multiple chronic conditions (), and in some cases had positive effects on community knowledge and well-being ().

The review also showed that HN allow an optimal redistribution of resources (; ; ; ; ), and favour cost reduction (), economy of scale and inter-organizational performance (; ).

Adaptive learning outcomes.

Relevant outcomes include: shared action learning (; ; ); increased use of information technology by health workers (; ; ; ); and innovation and improved responsiveness to patient needs (; ). In practice, developing interoperable health information systems (; ; ) enables creativity and organizational innovation (), transforming HN into ‘learning organisations’ ().

HN may improve the quality of clinical interprofessional collaboration (), foster research partnerships () and promote innovation projects (; ). However, the lack of interoperability between health information systems can hinder interpersonal interactions and information sharing (; ; ; ), thereby reducing the ability of HN to overcome geographical and organizational distances (; ).

Implementing HN sometimes transformed health policy processes and the system context (; , ). HN facilitate the implementation of healthcare policies that address the significant threats to health systems () and can have a transformative impact. This impact includes changing the market structure and the reduction of rivalry among healthcare providers (). For instance, the implementation of HN in The Netherlands led to their institutionalization by government bodies and strategic competition authorities, which established a monitoring programmeme to safeguard the public interest and ensure the affordability and accessibility of care (). In similar veins, HN have catalysed other systemic changes, such as introducing new care programmes within the health system () and adapting healthcare services to changing and increasing demands (). However, a lack of alignment between the HN and individual organizational goals can hinder collaborative dynamics ().

Finally, to enhance integration within HN, it is essential to have a high degree of coordination in core tasks (clinical pathways), a robust health information system enabling information sharing among healthcare facilities and a sufficient density of qualified health workers. In many low- and middle-income countries, poor health information systems and acute staff shortages often hamper the effectiveness of HN (; ).

Partnership drawbacks

Our scoping review has shown that HN can also have adverse unintended effects. These unintended effects are a persistent lack of organizational proximity due to paradoxical subcultures, power struggles, lack of autonomy and adaptive leadership practices, and increased competition over the reimbursement rate of clinical activities (). Without adjuvant financing reforms and appropriate incentives for inter-organizational collaboration, HN are unlikely to achieve efficient collaboration ().

Another negative consequence might be the persistent lack of alignment on goals, objectives, performance targets, reimbursement schemes and quality of care indicators. This often stems from the negative impact of merging healthcare facilities that lack appropriate organizational proximity (divergent corporate cultures, routines), leading to increased care fragmentation ().

Other scholars reported that the lack of technological proximity might arise when HN partners have an insufficient knowledge base for effectively using different information systems (). Paradoxically, overreliance on technology may also hinder effective interpersonal interactions among organizational participants in the networks (; ).

This might be alleviated by developing a shared information system or fostering interoperability between existing systems and exchanging network-wide electronic health records, appropriate task and role clarification and promotion of face-to-face interactions ().

Discussion

We synthesized evidence about the intricate working of collaborative dynamics within HN including hospitals. These HN are regarded as flexible, pragmatic forms of collaboration. Our review results suggest that HN are suitable for tackling complex, wicked healthcare issues (e.g. integrating healthcare delivery systems) ()(; ; ; , ; ).

Most scholars reporting the included studies adopted a political science perspective, focusing on concepts such as collaborative governance, deliberation and participative decision-making (; ; ; ). Other adopted organizational science perspectives ranged from change management, inter-organizational collaboration, innovation, relational coordination and resource exchange theories to network management ().

Our review highlighted the significance of considering HN structures as distinct organizational forms balancing top-down hierarchical control and bottom-up governance strategic alliances and committees (, ). Furthermore, in line with other scholars (; ), our scoping review underscores the importance of socioeconomic and political contexts in shaping and institutionalizing the hospital network initiatives.

The review also showed that lack of integration of care may lead to the rise of conflictual relationships and mistrust between health providers. Thus, the role of HN is to create a common joint interest in building inter-organizational collaboration (principled engagement) to build trustful relationships (mutual trust) and improve working relationships (shared motivation) (; ; ) and patient-centred collaboration practices ().

In line with previous studies (; ; ), this review reveals the heterogeneity of configurations of HN formed around hospitals. Such heterogeneity encompasses the nature of inter-organizational collaboration (mandatory or voluntary participation), type of management arrangements (normative vs contractual), degree of inclusiveness of partnerships (top-down vs participatory forms), financial and non-financial incentives, and the centrality of coordination (centralized HN in France vs loosely coupled networks in Belgium and Canada).

Finally, our review identified several drivers for inter-organizational collaboration reflected in other theoretical frameworks in the field of public management (; ; ; ; ; ), complexity science (; ) and learning health systems (), and health policy and system research (). These drivers highlight the importance of interdependence, risk sharing, scarcity of resources and the need to address interdependent challenges within multi-layered health systems that are inadequately addressed by traditional top-down governance structures. This is what called ‘wicked challenges’.

Lessons learnt

This scoping review highlighted some lessons about potential pathways through which HN functioning and synergy lead to positive overall inter-organizational performance. By partnership synergy, we mean the ability to combine the different resources, skills and perspectives of a network of organizations (; ; ; ). Potential pathways for increased synergy among HN partners and inter-organizational performance confirm existing literature observations about the determinants of effective partnership (; ; ; ; ; ; ). Such pathways include the following.

Trusting relationships

In line with previous studies (; ; ), trust building appears to be a robust mechanism for stimulating collaborative dynamics and partnership synergy. A reciprocal trust relationship helps reduce power differentials, increases shared motivation and mutual interest, and reinforces mutual respect and faith in collaboration.

Coordination and formalization

In hierarchical mandatory HN, as other scholars have also noted (; ; ; ), the formalization of operational procedures, equitable resource and information sharing, interoperability of health information systems and standardization of contractual arrangements will likely increase coordination, reduce duplication of services, and improve transparency, accountability, role clarity and efficiency of the partnership functioning. This may lead to the maintenance and sustainability of healthcare partnerships.

System leadership

Existing literature (; ; ; ; ) also suggests that complex HN require the development of systemic leadership that distributes power and enables psychological safety, trust relationships and cultural closeness (). Such leadership might reduce conflicts, facilitate cultural integration and increase trust, organizational flexibility, innovation, and learning and adaptation to wicked health challenges.

One size does not fit all: context matters!

The effectiveness of collaboration is contingent upon the context. It depends on contingency factors such as organizational structures, size and performance (; ; ). The ideal configurational model of inter-organizational collaboration in healthcare is yet to be determined, as no existing evidence supports a one-size-fits-all approach. Some configurations of health networks were developed through a transformative process and participatory decision-making, which benefits from bottom-up initiatives and long-term ownership of partners.

Bottom-up initiatives are considered to be suited for settings with solid connectivity, shared leadership based on voluntary cooperation and relational coordination with robust interpersonal and inter-organizational trust relationships (; ; ; ). Such dynamics involve processes of power-sharing and equitable workload distribution (; ). These also require effective management and visionary distributed leadership combined with power distribution and information sharing, close monitoring, timely issues resolution, performance monitoring and improved communication flows (; ).

However, bottom-up networks have downsides, including insufficient central coordination and slow decision-making due to lengthy consensus-building processes. Our scoping review has shown that lack of central coordination, in line with (; ; ), can lead to poor effectiveness and over-complex coordination mechanisms and decision processes. Similarly, ambiguity and fragmentation of roles and responsibilities (, ; ; ; ) and the unequal distribution of scarce resources might result in unintended consequences and failure of the implementation of well-designed HN (; ; ; , ).

Nevertheless, even in highly decentralized HN, the role of a lead healthcare institution with internal legitimacy is crucial in coordinating clinical pathways. This role is often played by teaching university hospitals, such as in oncology networks (; , ). However, in top-down healthcare networks, overemphasis on traditional hierarchy may hamper relational coordination (; ; ; ; ) and over complexify regulation procedures, such as in the case of bureaucratic area hospital grouping in France (; ; ; ; ).

In summary, bottom-up healthcare networks characterized by loose central coordination and strong interconnectivity might be well-suited for complex situations (; ; ). On the other hand, dominant hierarchical top-down healthcare networks are more suitable for situations with a high degree of stability and centralized healthcare systems. We suggest that a balance between formal top-down structures and organic network committees might prove appropriate. This approach allows for a natural equilibrium between standardization and centralized governance from control agencies and the need for flexibility, adaptability and reinforced collaborative management practices at operational levels.

Finally, research on practical components and determinants of healthcare collaboration is still inconclusive (; ; ; ). Therefore, it is unclear which configurational causation leads to effective collaboration (). In addition, some inter-organizational collaboration might lead to unintended outcomes such as paradoxical fragmentation of care due to a lack of congruence, reduced trust, conflicts and power imbalance between senior and middle-line managers (; ; ; ; ).

Research gaps

We suggest, in line with other scholars (; ; ) (), that future research needs to delve into the black box of collaborative dynamics by exploring the role of trust, power dynamics and the part of organizational configurations in the effectiveness and sustainability of collaborative dynamics. Researchers may reflect on theories such as the role agency theory (), social exchange () and resource exchange theories ().

To understand the intricate, collaborative dynamics in healthcare networks, researchers need to adopt innovative theory-driven approaches such as the realist evaluation (), qualitative comparative analysis () or inductive approaches such as ethnography () to understand what forms of collaborative networks work, for whom and in what context. Social network analysis () might prove helpful in unravelling the extent and centrality of governing bodies within health networks. Attention must be paid to distributed leadership and formal management practices in hospital networks, particularly in North African countries and the Eastern Mediterranean region, where collaborative governance within healthcare networks is under-explored.

Implications for practice and policy

We urge policymakers to adapt their dominant hierarchical approach in implementing healthcare networks by infusing collaborative dynamics with participatory decision-making processes. This can be done by implementing strategies and steering committees at decentralized administrative territories. Ministries of Health are urged to develop capacity-building programmes to enable future HN managers with systemic leadership capabilities to address complex health systems challenges. This can be done through on-site-based training and classroom training in themes such as collaborative leadership, system thinking, financial management, performance monitoring, health policy and power analysis. Policymakers need to invest more in the digitalization of healthcare information systems and fostering their interoperability to allow appropriate knowledge sharing and timely performance monitoring of area HN. This can be accelerated by using artificial intelligence and data analytics.

In the context of North African countries, as shown in other studies (; ), health systems are often centralized, with top-down hierarchical decision-making, including healthcare provision. The merger of diverse types of health provider entities (tertiary, secondary hospitals and primary care) may yield tensions and conflicts, cultural divergence and power struggles (e.g. the reluctance of senior managers to cede power to operational entities). In these settings, we highlight, as do previous studies (; ; ; ; ; ), the importance of developing system leaders who can integrate different health and social care institutions with diverse cultures and who can create a supportive environment enabling trust and respect between workforces and leaders.

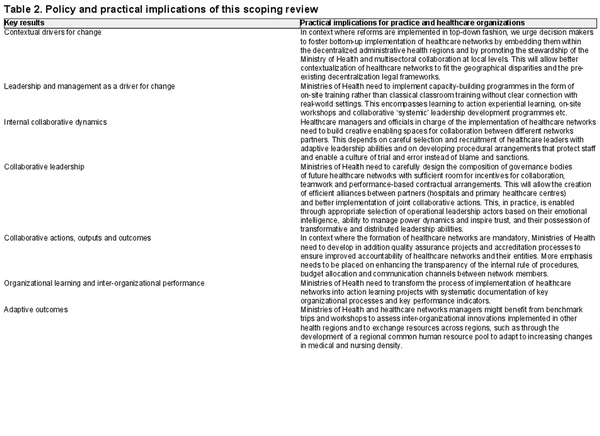

To better operationalize the results of our scoping review, we developed key lessons and practical recommendations for healthcare managers, as outlined in Table 2.

Limitations and validity of the study

In this scoping review, we made some trade-offs between comprehensiveness, feasibility and depth of the analysis (). Thus, some relevant studies may have been missed, including studies addressing the network of primary care, interprofessional collaboration and studies published before 2012 covered by previous reviews (; ). However, it was clear that we had reached theoretical saturation () during the coding process.

Further, the review did not focus on networks of care that exclusively merge primary care facilities. Future evidence synthesis might address the role of clinical collaboration and networks of primary care facilities, specifically in low- and middle-income countries addressed elsewhere ().

Most included studies relied on retrospective data, with some exceptions (; ). Thus, caution needs to be exercised in interpreting data related to the effectiveness of HN on overall performance, population health outcomes, financial performance and cost reduction (; ; ; ). Indeed, research evidence regarding the effectiveness of the components of HN on population health outcomes is inconclusive (; ; ; ).

The validity of this scoping study stems from its policy relevance—as it was identified through a priority setting exercise with national stakeholders as a knowledge gap. The validity of our findings is also reinforced by the systematic search and data charting processes using the framework synthesis approach (). In addition, the use of a highly cited collaborative governance framework reinforced the theoretical replication of collaborative governance theory across different contexts (). This scoping study has shown the utility of framework synthesis, a highly structured or systematic approach for both organizing and interpreting data in the process of generating and refining theories and in building a common understanding of concept among reviewer teams. Yet as a flexible synthesis approach, it allows iterative cycles of mapping and interpretation of complex interventions (; ; )—generating emergent themes as in metanarrative reviews and realist synthesis. Finally, the approach facilitates communication of key lessons learnt to stakeholders (; ).

Conclusion

Coordination of HN is a complex dynamic endeavour that requires new lenses for making sense of inter-organizational collaboration. HN foster horizontal inter-organizational collaboration, promote inter-organizational learning and facilitate patient referral systems. The health policy reforms in low- and middle-income countries might draw on pitfalls of the French model of ‘territorial hospital grouping’ and avoid over-reliance on top-down policy reforms in Morocco. One size does not fit all. In the context of Morocco, the top-down implementation of health network reforms needs to be balanced by creating a decentralized steering committee to steer future generations of health workers towards the path of sustainable collaborative governance.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of Dr Redouane Belouali Director of the International School of Public Health at the Mohammed VI University of health Sciences for his support to the Knowledge for Policy Centre initiative and the maintaining of engagement of stakeholders during early phases of the project.

References

- Addicott R, Mcgivern G, Ferlie E. 2007. The distortion of a managerial technique? The case of clinical networks in UK health care. British Journal of Management 18: 93–105.

- Agranoff R, Mcguire M. 2001. Big questions in public network management research. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 11: 295–326.

- Akhnif E, Macq J, Meessen B. 2019. The place of learning in a universal health coverage health policy process: the case of the RAMED policy in Morocco. Health Research Policy and Systems 17: 21.

- Alexander JA, Ye Y, Lee S-YD, Weiner BJ. 2006. The effects of governing board configuration on profound organizational change in hospitals. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 47: 291–308.

- Andersson J, Ahgren B, Axelsson SB, Eriksson A, Axelsson R. 2011. Organizational approaches to collaboration in vocational rehabilitation-an international literature review. International Journal of Integrated Care 11: e137.

- Ansell C, Gash A. 2008. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18: 543–71.

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. 2005. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8: 19–32.

- Audet M, Roy M. 2016. Using strategic communities to foster inter-organizational collaboration. Journal of Organizational Change Management 29: 878–88.

- Aunger JA, Millar R, Greenhalgh J et al. 2021. Why do some inter-organisational collaborations in healthcare work when others do not? A realist review. Systematic Reviews 10: 1–22.

- Bagwell MT, Bushy A, Ortiz J. 2017. Accountable care organization implementation experiences and rural participation: considerations for nurses. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration 47: 30–4.

- Barnes A, Brown GW, Harman S. 2016. Understanding global health and development partnerships: Perspectives from African and global health system professionals. Social Science & Medicine 159: 22–9.

- Belrhiti Z, Nebot Geralt A, Marchal B. 2018. Complex leadership in healthcare: A scoping review. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 7: 1073–84.

- Belrhiti Z, Van Belle S, Criel B. 2021. How medical dominance and interprofessional conflicts undermine patient-centred care in hospitals: historical analysis and multiple embedded case study in Morocco. BMJ Glob. Health 6: e006140.

- Bennett S, Glandon D, Rasanathan K. 2018. Governing multisectoral action for health in low-income and middle-income countries: unpacking the problem and rising to the challenge. BMJ -Global Health 3: e000880.

- Beran D, Perone SA, Alcoba G et al. 2016. Partnerships in global health and collaborative governance: lessons learnt from the division of tropical and humanitarian medicine at the geneva university hospitals. Globalization & Health 12: 14.

- Berends L, Ritter A, Chalmers J. 2016. Collaborative Governance in the reform of Western Australia’s alcohol and other drug sector. Australian Journal of Public Administration 75: 137–48.

- Berman P. 1995. Health sector reform: making health development sustainable. Health Policy 32: 13–28.

- Bernardo M, Valls J, Casadesus M. 2012. Strategic alliances: An analysis of Catalan hospitals. Revista Panamericana de Salud Publica/Pan American Journal of Public Health 31: 40–7.

- Blanchet K, James P. 2012. How to do (or not to do) .. a social network analysis in health systems research. Health Policy & Planning 27: 438–46.

- Booth A, Carroll C. 2015. How to build up the actionable knowledge base: the role of ‘best fit’ framework synthesis for studies of improvement in healthcare. BMJ Quality & Safety 24: 700–8.

- Bretas NJ, Shimizu H. 2017. Theoretical reflections on governance in health regions. Ciencia & Saude Coletiva 22: 1085–95.

- Breton M, Pineault R, Levesque J et al. 2013. Reforming healthcare systems on a locally integrated basis: is there a potential for increasing collaborations in primary healthcare? BMC Health Services Research 13: 1–12.

- Brinberg D, Wood R. 1983. A resource exchange theory analysis of consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Research 10: 330–8.

- Brunton G, Oliver S, Thomas J. 2020. Innovations in framework synthesis as a systematic review method. Research Synthesis Methods 11: 316–30.

- Carmone AE, Kalaris K, Leydon N et al. 2020. Developing a common understanding of networks of care through a scoping study. Health Systems & Reform 6: e1810921.

- Cazin L, Kletz F, Sardas J-C. 2022. Le regroupement des hôpitaux publics: l’action publique en régime d’apprentissage. Gestion Et Management Public 10: 77–99.

- CESE. 2016. Exigences de la régionalisation avancée et défis de l’intégration des politiques sectorielles. Rabat: Conseil Economique, Social et Environementale. http://www.cese.ma/media/2020/10/Rapport-Exigences-de-la-R%C3%A9gionalisation-avanc%C3%A9e.pdf, accessed 13 December 2023.

- Chu H-L, Chiang C-Y. 2013. The effects of strategic hospital alliances on hospital efficiency. The Service Industries Journal 33: 624–35.

- Clement JP, Mccue MJ, Luke RD et al. 1997. Strategic hospital alliances: Impact on financial performance. Health Affairs 16: 193–203.

- Collerette P, Heberer M. 2013. Governance of hospital alliances: lessons learnt from 6 hospital and non-hospital cases. Das Gesundheitswesen 75: e1–e4.

- Crosby BC, Bryson JM. 2010. Integrative leadership and the creation and maintenance of cross-sector collaborations. The Leadership Quarterly 21: 211–30.

- D’amour D, Ferrada-Videla M, San Martin Rodriguez L, Beaulieu M-D. 2005. The conceptual basis for interprofessional collaboration: Core concepts and theoretical frameworks. Journal of Interprofessional Care 19: 116–31.

- de Brún A, Mcauliffe E. 2020. Exploring the potential for collective leadership in a newly established hospital network. Journal of Health, Organization and Management 34: 449–67.

- Denis JL, Lamothe L, Langley A. 2001. The dynamics of collective leadership and strategic change in pluralistic organisations. The Academy of Management Journal 44: 809–37.

- de Pourcq K, de Regge M, van den Heede K et al. 2018. Hospital networks: how to make them work in Belgium? Facilitators and barriers of different governance models. Acta Clinica Belgica 73: 333–40.

- de Pourcq K, de Regge M, Van den Heede K et al. 2019. The role of governance in different types of interhospital collaborations: a systematic review. Health Policy 123: 472–9.

- de Regge M, de Pourcq K, van de Voorde C et al. 2019. The introduction of hospital networks in Belgium: The path from policy statements to the 2019 legislation. Health Policy 123: 601–5.

- de Vries M, Kenis P, Kraaij-Dirkzwager M et al. 2019. Collaborative emergency preparedness and response to cross-institutional outbreaks of multidrug-resistant organisms: a scenario-based approach in two regions of the Netherlands. BMC Public Health 19: 1–12.

- Donaldson L, Davis JH. 1991. Stewardship theory or agency theory: CEO governance and shareholder returns. Australian Journal of Management 16: 49–64.

- Emerson K. 2018. Collaborative governance of public health in low- and middle-income countries: lessons from research in public administration. BMJ -Global Health 3: e000381.

- Emerson K, Nabatchi T, Balogh S. 2011. An integrative framework for collaborative governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 22: 1–29.

- Essolbi A, Assarag B, Laariny SE et al. 2017. Evaluation des prestations de service:Étude de la performance des centres de santé au Maroc. Rabat: Office National des Droits de l’Homme.

- Field RI, Keller C, Louazel M. 2020. Can governments push providers to collaborate? A comparison of hospital network reforms in France and the United States. Health Policy 124: 1100–7.

- Fisher ES, Shortell SM, Savitz LA. 2016. Implementation science: a potential catalyst for delivery system reform. Jama 315: 339–40.

- Flemming K, Booth A, Garside R, Tunçalp Ö, Noyes J. 2019. Qualitative evidence synthesis for complex interventions and guideline development: clarification of the purpose, designs and relevant methods. BMJ -Global Health 4: e000882.

- Franco M, Duarte P. 2012. Continuous health care units as inter-organizational networks: A phenomenological study. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences 8: 55–79.

- Frankowski A. 2019. Collaborative governance as a policy strategy in healthcare. Journal of Health, Organization and Management 33: 791–808.

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. 2013. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology 13: 1–8.

- Gerkens S, Merkur S. 2010. Belgium: Health system review. Health Systems in Transition 12: 1–266.

- Gilson L, Nzinga J, Orgill M, Belrhiti Z. 2023. Health system leadership development in selected African countries: challenges and opportunities. In: Chambers N (ed). Research Handbook on Leadership in Healthcare. UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 686–98.

- Grint K. 2008. Wicked problems and clumsy solutions: the role of leadership. Clinical Leader 1: 11–25.

- Grootjans SJ, Stijnen M, Kroese M, Ruwaard D, Jansen M. 2022. Collaborative governance at the start of an integrated community approach: a case study. BMC Public Health 22: 1–11.

- Hermans S, Sevenants A, Declercq A et al. 2019. Integrated palliative care for nursing home residents: Exploring the challenges in the collaboration between nursing homes, home care and hospitals. International Journal of Integrated Care 19: 1–12.

- Hofmarcher MM, Oxley H, Rusticelli E 2007. Improved health system performance through better care coordination. Health working paper n°30, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs Health Committee DELSA/HEA/WD/HWP(2007)6.

- Hunter D, Perkins N. 2012. Partnership working in public health: The implications for governance of a systems approach. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 17: 45–52.

- Huxham C, Macdonald D. 1992. Introducing collaborative advantage: Achieving inter‐organizational effectiveness through meta‐strategy. Management Decision 30: 3.

- Hyrkäs P, Haukipuro L, Väinämö S et al. 2020. Collaborative innovation in healthcare: a case study of hospitals as innovation platforms. International Journal of Value Chain Management 11: 24–41.

- Jussila I, Goel S, Tuominen P. 2012. Governance of co-operative organizations: A social exchange perspective. Business and Management Research 1: 14–25.

- Karlsson M, Garvare R, Zingmark K, Nordström B. 2020. Organizing for sustainable inter-organizational collaboration in health care processes. Journal of Interprofessional Care 34: 241–50.

- Kavanagh MH, Ashkanasy NM. 2006. The impact of leadership and change management strategy on organizational culture and individual acceptance of change during a merger. British Journal of Management 17: S81–S103.

- Kelman S, Hong S. 2016. Hard, “soft,” or “tough love” management: What promotes successful performance in a cross-organizational collaboration? International Public Management Journal 19: 141–70.

- Kelman S, Hong S, Turbitt I. 2013. Are there managerial practices associated with the outcomes of an interagency service delivery collaboration? Evidence from British crime and disorder reduction partnerships. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 23: 609–30.

- Kingdom of Morocco 21. Loi cadre relative à la protection sociale. N°9-21. Morocco. N 9-21. Rabat. http://www.sgg.gov.ma/BO/FR/2873/2022/BO_7132_Fr.pdf, accessed 31 October 2023.

- Klinga C. 2018. The only constant is change: exploring the evolvement of health and social care integration. Karolinska Institutet (Sweden).

- Lang A. 2019. Collaborative Governance in Health and Technology Policy: The Use and Effects of Procedural Policy Instruments. Administration and Society 51: 272–98.

- Langlois ÉV, Daniels K, Akl EA, Organization WH. 2018. Evidence synthesis for health policy and systems: a methods guide. Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Researh World Health Organization. https://ahpsr.who.int/publications/i/item/2018-10-08-evidence-synthesis-for-health-policy-and-systems-a-methods-guide.

- Larsen ASA, Karlsen AT, Andersen B, Olsson NO. 2021. Exploring collaboration in hospital projects’ front-end phase. International Journal of Project Management 39: 557–69.

- Lasker RD, Weiss ES, Miller R. 2001. Partnership synergy: a practical framework for studying and strengthening the collaborative advantage. The Milbank Quarterly 79: 179–205.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. 2010. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Science 5: 1–9.

- Lyngsø AM, Godtfredsen NS, Frølich A. 2016. Interorganisational integration: Healthcare professionals’ perspectives on barriers and facilitators within the Danish healthcare system. International Journal of Integrated Care 16: 1–10.

- Madsen BS, Burau V. 2021. Relational coordination in inter-organizational settings. How does lack of proximity affect coordination between hospital-based and community-based healthcare providers? Journal of Interprofessional Care 35: 136–9.

- Madsen W, Redman-Maclaren M, Saunders V, O’mullan C, Judd J. 2021. Reframing health promotion research and practice in Australia and the Pacific: The value of arts-based practices. In: Corbin JH, Sanmartino M, Hennessy EA, Urke BH (eds). Arts and Health Promotion. Cham: Springer, 179–96.

- Mandell M, Steelman T. 2003. Understanding what can be accomplished through interorganizational innovations The importance of typologies, context and management strategies. Public Management Review 5: 197–224.

- Mate K, Bryan C, Deen N, Mccall J. 2017 Stella R. Quah. International Encyclopedia of Public Health (Springer) Second edition (Academic Press,) 347–56.

- Mccovery J, Matusitz J. 2014. Assessment of collaboration in US health care delivery: A perspective from systems theory. Social Work in Public Health 29: 451–61.

- Mccue MJ, Clement JP, Luke RD. 1999. Strategic hospital alliances do the type and market structure of strategic hospital alliances matter? Medical Care 37: 1013–22.

- Mervyn K, Amoo N, Malby R. 2019. Challenges and insights in inter-organizational collaborative healthcare networks An empirical case study of a place-based network. International Journal of Organizational Analysis 27: 875–902.

- Mintzberg Henry. 1989. Mintzberg on Management: Inside Our Strange World of Organizations. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Moscovice I, Christianson J, Johnson J, Kralewski J, Manning W. 1995. Rural hospital networks: implications for rural health reform. Health Care Financing Review 17: 53–67.

- Nauenberg E, Brewer CS, Basu K, Bliss MK, Osborne JW. 1999. Network structure and hospital financial performance in New York State: 1991-1995. Medical Care Research and Review 56: 415–39.

- Nicaise P, Grard A, Leys M, van Audenhove C, Lorant V. 2021. Key dimensions of collaboration quality in mental health care service networks. Journal of Interprofessional Care 35: 28–36.

- Nicaise P, Tulloch S, Dubois V et al. 2013. Using social network analysis for assessing mental health and social services inter-organisational collaboration: findings in deprived areas in Brussels and London. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 40: 331–9.

- O’Leary R, Choi Y, Gerard CM. 2012. The skill set of the successful collaborator. Public Administration Review 72: S70–S83.

- O’Leary R, Gazley B, Mcguire M, Bingham LB. 2009. Public managers in collaboration. In: O’Leary R, Bingham LB (eds.), The Collaborative Public Manager. Washington: Georgetown University Press, 1–12.

- O’Toole Jr, J L. 1997. Treating networks seriously: Practical and research-based agendas in public administration. Public Administration Review 57: 45–52.

- Otte-Trojel T, Rundall T, de Bont A, Van de Klundert J. 2017. Can relational coordination help inter-organizational networks overcome challenges to coordination in patient portals? International Journal of Healthcare Management 10: 75–83.

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. 2016. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews 5: 1–10.

- Ovseiko P, O’sullivan C, Powell S, Davies S, Buchan A. 2014. Implementation of collaborative governance in cross-sector innovation and education networks: evidence from the National Health Service in England. BMC Health Services Research 14: 1–14.

- Palumbo R, Cosimato S, Tommasetti A. 2017. Dream or reality? A recipe for sustainable and innovative health care ecosystems. The TQM Journal 29: 847–62.

- Pawson R, Tilley N. 1997. Realistic Evaluation. London Thousand Oaks New Delhi: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Peterman D. 1989. In: Fetterman DM (ed.), Ethnography; Step by Step, Applied Social Research Methods. 4th edn, UK: Sage Publications.

- Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H et al. 2015. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 13: 141–6.

- Plastrik P, Taylor M. 2006. In: Plastrik P, Taylor M, Cleveland JL (eds). Innovation Network for Communities. Washington: Island Press.

- Provan KG, Fish A, Sydow J. 2007. Interorganizational networks at the network level: A review of the empirical literature on whole networks. Journal of Management 33: 479–516.

- Radin BA, Agranoff R, Bowman A, Buntz CG. 1996. New Governance for Rural America: Creating Intergovernmenntal Partnerships. Rural America.

- Reeves S, Lewin S, Espin S, Zwarenstein M. 2011. Interprofessional Teamwork for Health and Social Care. Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Reimold KE, Faridi MK, Pekow PS et al. 2022. The relationship between governing board composition and medicare shared savings program accountable care organizations outcomes: an observational study. Journal of General Internal Medicine 37: 2462–8.

- Richardson WC, Allegrante JP. 2000. Shaping the future of health through global partnerships. In: Everett Koop C, Pearson CE, Schwarz MR (eds). Critical Issues in Global Health. New Jersey, USA: Wiley, 375–83.

- Rihoux B, Ragin CC. 2008. Configurational Comparative Methods: Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and Related Techniques, Applied Social Research Methods Series. Vol. 51, Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications.

- Robert E, Zongo S, Rajan D, Ridde V. 2022. Contributing to collaborative health governance in Africa: a realist evaluation of the Universal Health Coverage Partnership. BMC Health Services Research 22: 1–19.

- Roehrich JK, Lewis MA, George G. 2014. Are public–private partnerships a healthy option? A systematic literature review. Social Science & Medicine 113: 110–9.

- Romiti A, Del Vecchio M, Grazzini M. 2018. Models for governing relationships in healthcare organizations: Some empirical evidence. Health Services Management Research 31: 85–96.

- Romiti A, Del Vecchio M, Sartor G. 2020. Network governance forms in healthcare: empirical evidence from two Italian cancer networks. BMC Health Services Research 20: 1–16.

- Royaume du Maroc C. 2013. Les soins de santé de base vers un accès équitable et généralisé. Rabat, Maroc: Conseil Economique, Social et Environnemental.

- Salancik GR, Pfeffer JJASQ. 1978. A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. 224–53.

- Sandfort J, Milward HB. 2008. Collaborative service provision in the public sector.

- Sarcone DM, Kimmel CM. 2021. Characteristics of successful health alliance strategies: Evidence from rural healthcare experiences. Journal of Healthcare Management 66: 141–54.

- Schneider H, Zulu J, Mathias K, Cloete K, Hurtig A. 2019. The governance of local health systems in the era of Sustainable Development Goals: reflections on collaborative action to address complex health needs in four country contexts. BMJ -Global Health 4: 1–8.

- Scott TA, Thomas CW. 2017. Winners and losers in the ecology of games: Network position, connectivity, and the benefits of collaborative governance regimes. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 27: 647–60.

- Sequeira D’Mello B, Bwile P, Carmone AE et al. 2020. Averting maternal death and disability in an urban network of care in Dar ES Salaam, Tanzania: a descriptive case study. Health Systems & Reform 6: e1834303.

- Shortell SM. 2016. Applying organization theory to understanding the adoption and implementation of accountable care organizations: commentary. Medical Care Research and Review 73: 694–702.

- Short A, Phillips R, Nugus P et al. 2015. Developing an inter-organizational community-based health network: an Australian investigation. Health Promotion International 30: 868–80.

- Snowden D, Stanbridge P. 2004. The Landscape of Management: Creating the context of understanding social complexity. E:co 6: 140–8.

- Spitzmueller M, Jackson T, Warner L. 2020. Collaborative Governance in the age of managed behavioral health care. Journal of the Society for Social work and Research 11: 615–42.

- Stacey RD. 2007. Strategic Management and Organisational Dynamics: The Challenge of Complexity to Ways of Thinking about Organisations. London, UK: Pearson education.

- Sturmberg JP, O’halloran DM, Martin CM. 2012. Understanding health system reform–a complex adaptive systems perspective. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 18: 202–8.

- Sus A, Organa M, Sulich A. 2019. Effectiveness of Relations in the inter-organizational oncological network in poland-research assumptions. Transformations in Business & Economics 18: 745–66.

- Taylor-Powell E, Rossing B, Geran J. 1998. Evaluating collaboratives: Reaching the potential. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin–Extension, Cooperative Extension, Program Development and Evaluation.

- Thompson F, Cantor J, Houston R. 2020. Control versus administrative discretion in negotiating voluntary P4P networks: The case of medicaid accountable care organizations. ADMINISTRATION & SOCIETY 52: 81–110.

- Thomson AM, Perry JL. 2006. Collaboration processes: Inside the black box. Public Administration Review 66: 20–32.

- Thomson AM, Perry JL, Miller TK. 2014. Linking Collaboration Processes and Outcomes: Foundations for Advancing Empirical Theory. Big Ideas in Collaborative Public Management. New York, USA: Routledge.

- Tippin GK, Maranzan KA, Mountain MA. 2017. Client outcomes associated with interprofessional care in a community mental health outpatient program. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health 35: 83–96.

- Tourmente D. 2016. Les Groupements Hospitaliers de Territoires: missions et gouvernance des nouveaux outils de coopération.

- Tremblay D, Touati N, Poder T et al. 2019. Collaborative governance in the Quebec Cancer Network: A realist evaluation of emerging mechanisms of institutionalization, multi-level governance, and value creation using a longitudinal multiple case study design. BMC Health Services Research 19: 1–4.

- Tremblay D, Touati N, Usher S et al. 2021. Patient participation in cancer network governance: a six-year case study. BMC Health Services Research 21: 929.

- Turrini A, Cristofoli D, Frosini F, Nasi G. 2010. Networking literature about determinants of network effectiveness. Public Administration 88: 528–50.

- Van Der Schors W, Roos A, Kemp R, Varkevisser M. 2021. Inter-organizational collaboration between healthcare providers. Health Services Management Research 34: 36–46.

- Vangen S, Huxham C. 2003. Nurturing collaborative relations: Building trust in interorganizational collaboration. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 39: 5–31.

- Vindrola-Padros C, Ramsay AIG, Black G et al. 2022. Inter-organisational collaboration enabling care delivery in a specialist cancer surgery provider network: A qualitative study. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy 27: 211–21.

- Wang H, Ran B. 2022. Network governance and collaborative governance: A thematic analysis on their similarities, differences, and entanglements. Public Management Review 25: 1187–211.

- Wankah P, Guillette M, Dumas S et al. 2018. Reorganising health and social care in Québec: a journey towards integrating care through mergers. London Journal of Primary Care 10: 48–53.

- Waring J, Crompton A. 2019. The struggles for (and of) network management: an ethnographic study of non-dominant policy actors in the English healthcare system. Public Management Review 22: 297–315.

- Williams B, Hummelbrunner R. 2010. Systems Concepts in Action: A Practitioner’s Toolkit. 1st edn. California, USA: Stanford University Press.

- Witter S, Boukhalfa C, Cresswell JA et al. 2016. Cost and impact of policies to remove and reduce fees for obstetric care in Benin, Burkina Faso, Mali and Morocco. International Journal for Equity in Health 15: 1–19.

- Witter S, Sheikh K, Schleiff M. 2022. Learning health systems in low-income and middle-income countries: exploring evidence and expert insights. BMJ -Global Health 7: e008115.

- Wood DJ, Gray B. 1991. Toward a comprehensive theory of collaboration. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 27: 139–62.

- Yin RK. 2016. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish. New York, London: The Guilford Press.