Background

In Australia, breast cancer affects one in seven women and is the second most common cause of female mortality (). When detected in its pre-clinical stage, breast cancer mortality and morbidity are reduced. The gold standard diagnostic imaging test for breast cancer is mammography, with women aged between 50 and 74 years offered free biannual screening through BreastScreen Australia sites. Over many years, patient information sheets have been developed by BreastScreen NSW to educate women about the risks of breast cancer and the benefits of screening mammography and to support informed consent for the procedure (). As a multicultural country, information sheets are published in 28 community languages, all aimed at evoking participation in screening by enabling informed decision-making.

ChatGPT is a generative pre-trained transformer (GPT) large language model by OpenAI, trained to process and generate human-like text (). The artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot was made publicly available on 30 November 2022. The GPT3.5 architecture has captured significant interest, including in health, where it has been used or proposed to offer benefits in medical writing and provide health education (). At the time of writing, there was a paucity of scientific evaluations of the accuracy, appropriateness, clarity, and currency of ChatGPT medical writing targeted at professionals and patients. It has been found that both ChatGPT4 and ChatGPT3.5 exhibited a moderate level of accuracy in determining the appropriate imaging steps for breast cancer screening and the assessment of breast pain (). Most research on ChatGPT refers specifically to GPT3.5, and most discussions of ChatGPT include a glance forward at the educational possibilities presented by the more advanced GPT4. GPT4 was released as a paid subscription in March 2023, although some of the features were not yet enabled (e.g., image inputs); GPT4 is also constrained by the September 2021 learning cut-off. However, GPT4 problem-solving and accuracy are reported to be superior to GPT3.5 by 60% ().

However, to be useful, health education information must be suitable for many different audiences with variable health literacies and contribute to public health and positive health behaviors, including participation in breast screening ().

The internet is a well-established source of health information, with as many as 80% of internet users searching for health and medical information (). Search engines can return various sources with incorrect or misleading information, leaving the patient to navigate and determine what advice to accept as real. These internet resources often lack quality and patient readability and create confusion (). Importantly, deciphering information among numerous web pages returned for any search requires a high degree of health literacy. Indeed, the accessibility of health and health information along socioeconomic lines can be exacerbated in the digital space due to variations in health literacy (). Generative AI like ChatGPT can address health literacy limits by responding consistently to specific inquiries. This assumes that the nature of the query is within the training set of the AI tool. A recent comparison of internet search engines with generative AI reveals the superiority of ChatGPT over Google for medical knowledge but inferiority for medical recommendations (). In some ways, this defines the purpose of ChatGPT, which itself reminds patients that individual medical advice and diagnosis are not the remit of ChatGPT and that such advice and recommendations should be sought from an expert health practitioner. ChatGPT should not be used to replace clinical decision-making. In health care practice, concerns have also been raised about the data sets applied in ChatGPT training (; ). These concerns highlight the potential for bias, which may constrain ChatGPT capabilities and knowledge and give rise to factual inaccuracies, unlike dedicated breast screening promotional material that ensures quality-controlled information. Between 2020 and 2022, BreastScreen Australia’s participation rate for eligible women was only 48% compared to the program’s 70% target (). Misinformation can cause uncertainty among women, which can impact their willingness to participate in screening programs. This, in turn, results in missed opportunities for the early detection of breast cancer, potentially resulting in delayed diagnoses and poorer prognoses, including increased mortality rates.

Purpose

This research aims to evaluate the capability of ChatGPT to generate suitable patient information concerning screening mammography that is fit for purpose, including the understandability and actionability of the material provided. Patient information relating to screening mammography plays an important role in educating patients with sufficient insight so they can make an informed decision regarding breast cancer risk and the benefits of screening; ideally such information should prompt positive health behavior and participation in breast screening. ChatGPT presents as an alternative to traditional health promotion practice that warrants investigation. The secondary aims were to compare the accuracy of information provided between GPT3.5 and GPT4 and to benchmark ChatGPT information against the gold standard BreastScreen NSW health promotion material.

Method

A Conversation With ChatGPT

To evaluate the capabilities of ChatGPT for generating patient information concerning screening mammography, ChatGPT was asked to generate a patient information sheet for screening mammography, and separate conversations were started with both versions of ChatGPT between 13 April and 29 May 2023. The following seven questions derived from key messaging in a BreastScreen NSW benchmark exemplar (BreastScreen NSW, 2023) were used to establish the context of the conversation: Question 1: What is mammography?; Question 2: What is the difference between screening mammography and diagnostic mammography?; Question 3: Is screening mammography effective in saving lives from breast cancer?; Question 4: Who should have screening mammography?; Question 5: What about breast implants, breast surgery, dense breasts, and breast radiation therapy?; Question 6: How does a mammogram manage implantable devices like an implantable cardiac device (ICD)? Question 7: Who should avoid having mammography?

ChatGPT3.5 and 4 were then asked the following questions: Question 8: Can you write a patient information sheet suitable for providing sufficient information that it could be used to gain informed consent for a screening mammogram?; Question 9: Please provide references and citations that support your claims of safety and benefit.; Question 10: But what about scientific research and trials published in peer-reviewed journals?

BreastScreen NSW Benchmark

An online search was undertaken for the latest versions of publicly available material published by BreastScreen NSW relating to the breast screening procedure. The patient information sheet Breast Screening and You () was selected by author consensus as best aligned to the task and used as a benchmark against the content of the ChatGPT information sheets. The Australian government-funded publication provides accurate and up-to-date information on screening designed to maximize participation rates and is a known and credible source of information. The publication Breast Screening and You () has been designed to accommodate all health literacies, promote understanding of breast cancer and the benefits of screening and its process as well as to have a message that is understandable and actionable.

Evaluating ChatGPT

The Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool for printed materials (PEMAT-P) patient information sheet () was used to assess the ChatGPT 3.5 and ChatGPT4.0 responses and the BreastScreen NSW information sheet. The PEAMAT-P has previously been used in Australia to assess health promotion materials and is validated as a tool for use by both professionals and the general public, including those with low health literacy (; ). The PEMAT-P is considered an effective supplementary tool to reading alone (). Each ChatGPT information sheet was reviewed by members of the expert panel, who have clinical experience in breast screening and have published extensively on the topic. The overall score for each material content category was averaged to calculate mean scores for each category, with standard deviation.

The CDC Clear Communication Index was also used to assess each information sheet to further assess the language used in each communication. The index assesses seven key areas of communication—the main message or call to action, use of plain language, information design, state of science, behavioral recommendations, numbers, and risk. These criteria are based on the index used to develop and assess communication for diverse audiences ().

The authors compared the content of the three information sheets and recorded key omissions and misinformation.

The references provided were analyzed for accuracy.

Results

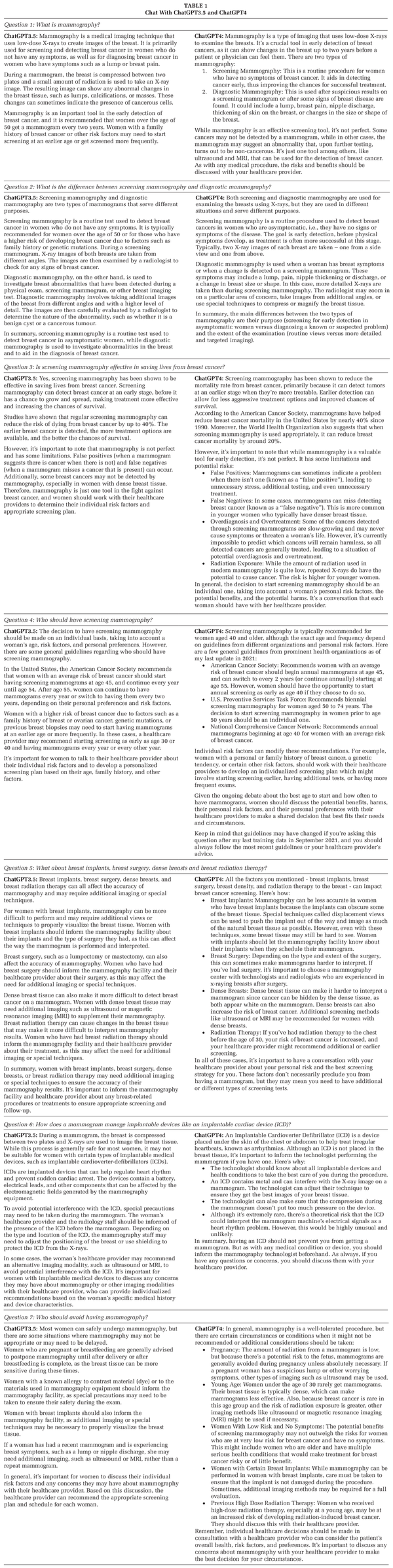

The conversations with ChatGPT3.5 and ChatGPT4 in response to questions one to six are reported in Table 1.

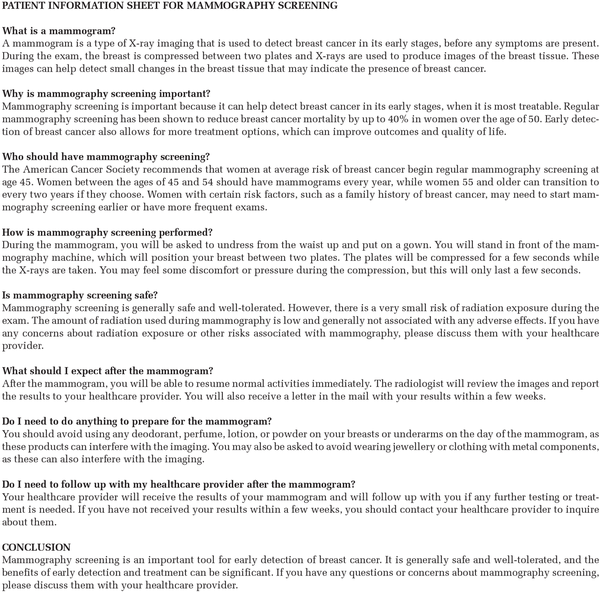

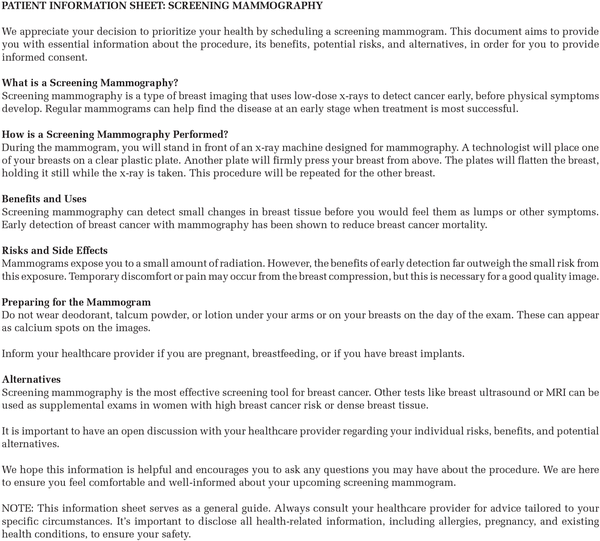

The patient information sheets generated by GPT3.5 and GPT4 responses are reported in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Figure 1

GPT3.5 Generated Patient Information Sheet

Figure 2

GPT4 Generated Patient Information Sheet

When asked to provide references and citations that supported claims of safety and benefit in the patient information sheet, Chat 3.5 responded:

“Sure, here are some references and citations to support the claims made in the patient information sheet” and provided the following references which are reported here verbatim: The American Cancer Society. (2021). Breast cancer early detection and diagnosis. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/breast-cancer/screening-tests-and-early-detection/mammograms.html; National Cancer Institute. (2021). Mammograms. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.gov/types/breast/mammograms-fact-sheet; American College of Radiology. (2021). Mammography. Retrieved from https://www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/Radiology-Safety/Mammography, and National Breast Cancer Foundation. (2021). Mammogram. Retrieved from https://www.nationalbreastcancer.org/mammogram/

Chat GPT3.5 further explained that:

These sources provide evidence that mammography screening is a safe and effective tool for early detection of breast cancer, with the potential to reduce breast cancer mortality by up to 40% in women over the age of 50. The risk of radiation exposure during mammography is low, and the benefits of early detection and treatment of breast cancer generally outweigh any potential risks. However, it is important to discuss any concerns or questions with a healthcare provider.

ChatGPT4 automatically included the following references in the original response to develop a patient information sheet which are reported here verbatim: American Cancer Society. (2019). Mammograms. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org and U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA). (2020). Mammograms. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov

When asked about scientific research and trials published in peer-reviewed journals, Chat GPT3.5 responded:

“Certainly, here are some references to scientific research and trials published in peer-reviewed journals that support the safety and benefit of mammography” and provided the following references which are reported here verbatim: Duffy, S. W., et al. (2020). Effect of mammographic screening from age 40 years on breast cancer mortality at 10 years’ follow-up: a randomised controlled trial; The Lancet, 395(10242), 371–380; . Screening for breast cancer: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 315(13), 1404–1414; Kerlikowske, K., et al. (2015). Identifying women with dense breasts at high risk for interval cancer: a cohort study. Annals of Internal Medicine, 162(10), 673–681 and Bleyer, A., et al. (2016). Effectiveness of screening mammography among women aged 40 to 49 years and 50 to 69 years: comparison of relative and absolute benefit. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(10), 1541–1548.

GPT4 replied:

“Sure, here are some specific references to the studies and guidelines I mentioned ” and provided the following references which are reported here verbatim: Tabár L, Yen MF, Vitak B, Chen HH, Smith RA, Duffy SW. Mammography service screening and mortality in breast cancer patients: 20-year follow-up before and after introduction of screening. Lancet. 2003 Apr 26;361(9367):1405–10; Miller AB, Wall C, Baines CJ, Sun P, To T, Narod SA. Twenty five year follow-up for breast cancer incidence and mortality of the Canadian National Breast Screening Study: randomised screening trial. BMJ. 2014 Feb 11;348:366; Siu AL; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Breast Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016 Feb 16;164(4):279–96 and Gøtzsche PC, Jørgensen KJ. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jun 4;(6):CD001877.

References from the BreastScreen NSW patient information sheet were located at the end of the publication (BreastScreen NSW, 2023).

The PEMAT-P and CDC Index scores are presented in Table 2 (). ChatGPT4.0 was scored higher by the expert panel than ChatGPT3.5 for understandability, actionability, and clear communication.

In this study, the first citation for GPT3.5 is not real. The citation appears to hybridize two articles (; ). The second citation for GPT3.5 also does not exist and could be a mix of several articles (; ). The last GPT3.5 citation is also fabricated, presumably from a hybridisation (; ). The third link provided by GPT3.5 is not valid. Neither of the GPT4 references is correct, although both organizations will provide information on mammograms. The references used in the BreastScreen NSW patient information sheet are accurate as cited.

Discussion

Educational health behavior change campaigns to increase participation in the BreastScreen Australia breast screening program are regularly made accessible across mass media. In addition, print material is also available for women to take home to read or review at their appointments, including the BreastScreen NSW patient information sheet used for benchmarking in this study. The clinically available patient information sheet Breast Screening and You () was used to critique the ChatGPT-generated versions of this study. GPT3.5 provided good general information but lacked the detail required to gain informed consent. This may be because ChatGPT has not had the necessary training to achieve reproducibility of information at acceptable standards. Explaining the procedure itself, for example, was correct at a general level but missed key details that a patient should expect to understand before progressing with the procedure, which has the potential to discourage participation. The responses for both GPT3.5 and GPT4, as noted by the authors, reflect a U.S.-centric bias related to a ChatGPT construct which can produce misleading or incorrect information in an alternate setting, such as BreastScreen NSW in this instance. Some notable omissions from the GPT3.5 patient information sheet included not mentioning a family history of breast cancer or that most women with breast cancer (90%) do not have a family history; that breast cancer is a common disease or that it increases with age; breast cancer risk factors other than family history or genetic mutations; a screening mammogram can detect small breast cancers before symptoms are present; that a referral is not required; and requirements for imaging pregnancy or breastfeeding patients.

While ChatGPT3.5 provided details of screening and patient age, the information was considered U.S.-centric and, therefore, incorrect in the Australian context. The information provided did not outline that screening mammography is for women without symptoms or direct women with symptoms to the appropriate medical pathway; it also did not suggest wearing a two-piece outfit so the top can be removed without removing the bottom despite indicating that patients would be in a gown from the waist up. The procedure was not adequately explained, nor were the two projections taken and implied positioning was automated. The information also did not indicate the necessity to advise staff in advance if they have implants, implantable devices, a history of breast surgery or a history of breast irradiation. Advice for women under the age of 40 or for those with dense breasts was not provided. The frequency of screening or when the next mammogram would be needed was not explained. Mammogram limitations, including false positives and false negatives, were not explained, and while mentioning potential discomfort, it did not indicate the procedure could be stopped in a small portion of women where the procedure is too painful. This misinformation may dissuade participation.

Like GPT3.5, the GPT4 patient information sheet omitted mentioning: a family history of breast cancer or that most women with breast cancer (90%) do not have a family history; indicating breast cancer is a common disease or that it increases with age; breast cancer risk factors other than family history or genetic mutations; that a referral is not required; directing women with symptoms to the appropriate medical pathway; a suggestion to wear a two-piece outfit so the top can be removed without removing the bottom despite indicating that patients would be in a gown from the waist up. While mentioning potential discomfort, it did not indicate that the procedure could be stopped in a small portion of women where the procedure is too painful; advice for women under the age of 40 years or those with dense breasts; indication of the frequency of screening or when the next mammogram would be needed. The information provided did not explain the limitations of mammography, including false positives and false negatives; it did not mention requirements for pregnancy or breastfeeding patients; it did not adequately explain the procedure or the two projections taken.

GPT4 provided some information not evident in the GPT3.5 version, including advice to inform staff about breast implants and that screening mammograms can detect small breast cancers before symptoms are present. GPT4 did, however, omit some important pieces of information that the GPT3.5 version had included. This information includes who mammographic screening is targeted at or designed for (e.g., age requirements); details of the reporting process and timeline, and the fact that if further investigation is required, patients will be contacted. Anecdotally, the impression is that GPT4 provided a better written and more appropriate information sheet.

GPT3.5 generated plausible information for a screening mammography patient information sheet; however, the document contains errors, misinformation, and omits key information, making it inappropriate for education and health promotion. GPT4 produced a more appropriate information sheet, although omissions were still an issue. Reliance on ChatGPT by patients as a source of information, based on the use of search engines as a source of medical advice (e.g., “Dr Google”), is likely to become more common. It has been reported that before contacting a medical practitioner, 87% of Australian patients access medical information using search engines such as Google and WebMD. It has also been reported that seeking health information using the internet is significantly underpinned by trust in the site (). Whether this trust translates to ChatGPT is unknown, especially given concerns about the data sets used in its training. In addition, the ChatGPT model operates in a self-contained manner, lacking the capability to copy from other sources and access the internet for information retrieval when generating responses; instead, it predicts the next part of a sentence using patterns learned during training. The real-time generation of answers to questions in a convincing way obviates the need for trawling through multiple pages on a search engine report; but still requires a high degree of health literacy equivalent to that needed to review websites. As evidenced, the information provided by ChatGPT does not currently equate to accurate information or information that is understandable or actionable. This presents a challenge for using ChatGPT as an information source in health education settings where accuracy and clarity are critical. ChatGPT-generated content might not meet the standards for conveying accurate and understandable health-related information.

A recent study by reported that the reliability of medical information provided by ChatGPT answers compared to guideline recommendations across five medical conditions was 60%. Consequently, this lack of reliability could increase the demands on health care educators and staff, including radiologists and radiographers, to spend additional time clarifying misinformation and misconceptions produced by ChatGPT information. But a greater concern is that the poor understandability and actionability of the information provided by ChatGPT3.5 and ChatGPT4.0 combined with a low CDC Index score for actionability may result in women not participating in the screening program, putting them at risk of missed breast cancer and death (Table 2). A number of “ChatGPT type” errors or mistakes were detected in the GPT3.5 patient information sheet. This includes the use of outdated terminology (e.g., referring to “plates”). The errors included a variety of previously defined ChatGPT learning inaccuracies (), including “hallucination” (incorrect information presented as fact by the chatbot), and content that is plausible but incorrect upon checking. Furthermore, there was an AI “illusion error of similarity” (e.g., the reporting process is similar but different), “delusion” as a result of AIs false beliefs producing wrong information (e.g., the implication that the equipment positions the patient rather than a radiographer), “delirium” with sophisticated answerers generated by AI from a confused algorithm (e.g., a small risk of radiation exposure during the procedure rather than a small risk from radiation during the procedure), “confabulation of fake information” (e.g., the fabricated Bleyer citation), and the extrapolation of a logical, although incorrect, extension of known information (e.g., advice regarding jewelry removal as an extrapolation from other imaging procedures).

These errors were reduced in the GPT4 version of the information sheet but it still included incorrect terminology (e.g., plate) and inaccurate protocol (e.g., two projections instead of four). GPT4 was more patient-facing in language and structure, less U.S.-centric in content, more succinct, and provided a disclaimer, advice, and medical information.

ChatGPT is known for the plausibility of the information it provides rather than its accuracy. The propensity to present incorrect information as fact occurs when the model has had to guess combinations of information as the detail of the original information is lost (hallucination) (). In this study, ChatGPT has fabricated plausible-looking references that do not exist and several that support the information provided. ChatGPT cannot analyze the sources it uses for accuracy and, as such, is providing educational material without a source of truth.

The primary purpose of a patient information sheet in screening mammography is to educate women by providing sufficient information to make an informed decision about participation in screening mammography and undertaking the procedure. The BreastScreen NSW patient information sheets have been developed for understandability, actionability, and clear communication (Table 1) to attract women in the BreastScreen target age group to participate in screening taking into account their own perspectives ().

The information sheet is also an important generator of patient questions, which is a crucial part of informed consent across all health literacies. Using ChatGPT for mammography information risks affecting patient involvement and experience due to inaccuracies. ChatGPT might be better suited to language conversion of exemplar clinical patient information sheets where English is a second language, although ChatGPT has been reported to be inferior in non-English language text generation (). Comparison across the multiple languages of the BreastScreen NSW exemplar was outside the scope of this study. Nonetheless, GPT4 provided an improved information sheet over GPT3.5, which could soon be deemed fit for purpose with continued training. However, reliance remains on the reader to assess the plausibility of the information provided, which may not suit all levels of health literacy.

A limitation of this study is that it did not include end users (the general public) in the PEMAT-P or CDC Index analysis, and the results may be biased due to the authors’ level of health literacy and clinical experience in this field.

Implications for Practice

ChatGPT has been shown to be an unreliable and inaccurate source of information concerning breast screening and may, as a consequence, not prompt the behavioral changes needed to reduce morbidity and mortality from breast cancer if used as a standalone source of truth. As a result, support for patients seeking additional information ahead of screening mammography is needed as it risks misinformation and confusion. This is of concern as it has implications for participation and practice. When women seek health education relating to mammography screening from ChatGPT, participation may decrease, and it is also foreseeable that there may be increased demands on the health care system to address ChatGPT’s inaccuracies. Also, health care educators may need to rectify information deficiencies. This is counter to the purported advantages of ChatGPT, and it could decrease efficiency.

Conclusion

ChatGPT is freely available and is an exciting and innovative tool for information generation and answering patient questions, but educators must be aware that it currently has limited accuracy when generating patient information for screening mammography, with the potential to negatively impact breast screening education and program participation. Access to ChatGPT4 is reported to have increased accuracy in the information provided, presenting a secondary barrier to health education for those who cannot afford it. Continued training of ChatGPT and the release of more advanced freely and publicly available versions of the AI chatbot may improve the PEMAT-P and CDC Index scores against benchmark health promotion material to a point where ChatGPT becomes a trusted easily accessible source of information for all health literacies. Health educators must recognize that Chat GPT is not at that point yet.

Authors’ Note: We would like to acknowledge the contribution of ChatGPT (version 3.5), a language model developed by OpenAI (https://openai.com/), in generating some of the text in this manuscript. The model was accessed between April 13 and April 21, 2023,

Kelly Spuur

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0285-9962

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2021). BreastScreen Australia monitoring report 2021. https://doi.org/10.25816/btjk-3q46

- Ayoub N. F., Lee Y. J., Grimm D., Divi V. (2024). Head-to-head comparison of ChatGPT versus Google search for medical knowledge acquisition. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 170(6), 1484–1491. https://doi.org/10.1002/ohn.465

- Azer S. A., Al Olayan T. I., AlGhamdi M. A., AlSanea M. A. (2017). Inflammatory bowel disease: An evaluation of health information on the internet. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 23(9), 1676–1696. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i9.1676

- Baur C., Prue C. (2014). The CDC clear communication index is a new evidence-based tool to prepare and review health information. Health Promotion Practice, 15(5), 629–637. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839914538969

- Biswas S. (2023). ChatGPT and the future of medical writing. Radiology, 307(2), Article e223312. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.223312

- Bleyer A., Baines C., Miller A. B. (2016). Impact of screening mammography on breast cancer mortality. International Journal of Cancer, 138(8), 2003–2012. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29925

- BreastScreen NSW. (2023). Breast screening and you. https://www.breastscreen.nsw.gov.au/globalassets/breastscreen-nsw/brochures/breast-screening-and-you-brochure.pdf

- Currie G. M. (2023). Academic integrity and artificial intelligence: Is ChatGPT hype, hero or heresy? Seminars in Nuclear Medicine, 53(5), 719–730. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2023.04.008

- Deng J., Lin Y. (2023). The benefits and challenges of ChatGPT: An overview. Frontiers in Computing and Intelligent Systems, 2(2), 81–83. https://doi.org/10.54097/fcis.v2i2.4465

- Duffy S. W., Vulkan D., Cuckle H., Parmar D., Sheikh S., Smith R. A., Evans A., Blyuss O., Johns L., Ellis I. O., Myles J., Sasieni P. D., Moss S. M. (2020). Effect of mammographic screening from age 40 years on breast cancer mortality (UK Age trial): Final results of a randomised, controlled trial. The Lancet Oncology, 21(9), 1165–1172. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30398-3

- Kerlikowske K. (1997). Efficacy of screening mammography among women aged 40 to 49 years and 50 to 69 years: Comparison of relative and absolute benefit. JNCI Monographs, 1997(22), 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/jncimono/1997.22.79

- Marcu A., Black G., Whitaker K. L. (2018). Variations in trust in Dr Google when experiencing potential breast cancer symptoms: Exploring motivations to seek health information online. Health, Risk & Society, 20(7–8), 325–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2018.1550742

- Mastroianni F., Chen Y. C., Vellar L., Cvejic E., Smith J. K., McCaffery K. J., Muscat D. M. (2019). Implementation of an organisation-wide health literacy approach to improve the understandability and actionability of patient information and education materials: A pre-post effectiveness study. Patient Education and Counseling, 102(9), 1656–1661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.03.022

- Moss S. M., Cuckle H., Evans A., Johns L., Waller M., Bobrow L. (2006). Effect of mammographic screening from age 40 years on breast cancer mortality at 10 years’ follow-up: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet (British Edition), 368(9552), 2053–2060. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69834-6

- National Breast Cancer Foundation. (2023). Breast cancer stats. https://nbcf.org.au/about-breast-cancer/breast-cancer-stats/

- Nelson H. D., Cantor A., Humphrey L., Fu R., Pappas M., Daeges M., Griffin J. (2016). U.S. Preventive services task force evidence syntheses, formerly systematic evidence reviews. In Screening for breast cancer: A systematic review to update the 2009 U.S. Preventive Services task force recommendation. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US).

- Nelson H. D., Fu R., Cantor A., Pappas M., Daeges M., Humphrey L. (2016). Effectiveness of breast cancer screening: Systematic review and meta-analysis to update the 2009 U.S. Preventive services task force recommendation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 164(4), 244–255. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-0969

- Rao A., Kim J., Kamineni M., Pang M., Lie W., Dreyer K. J., Succi M. D. (2023). Evaluating GPT as an adjunct for radiologic decision making: GPT-4 versus GPT-3.5 in a breast imaging pilot. Journal of the American College of Radiology, 20(10), 990–997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2023.05.003

- Roughead T., Sewell D., Ryerson C. J., Fisher J. H., Flexman A. M. (2016). Internet-based resources frequently provide inaccurate and out-of-date recommendations on preoperative fasting: A systematic review. Anesthesia and Analgesia, 123(6), 1463–1468. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000001590

- Sallam M. (2023). ChatGPT utility in healthcare education, research, and practice: Systematic review on the promising perspectives and valid concerns. Healthcare, 11(6), 887. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11060887

- Sanderson K. (2023). GPT-4 is here: What scientists think. Nature, 615(7954), 773. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-00816-5

- Seghier M. L. (2023). ChatGPT: Not all languages are equal. Nature, 615(7951), 216. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-00680-3

- Shoemaker S. J., Wolf M. S., Brach C. (2014). Development of the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT): A new measure of understandability and actionability for print and audiovisual patient information. Patient Education and Counseling, 96(3), 395–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2014.05.027

- Smith B., Magnani J. W. (2019). New technologies, new disparities: The intersection of electronic health and digital health literacy. International Journal of Cardiology, 292, 280–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.05.066

- Sobieszek A., Price T. (2022). Playing games with AIs: The limits of GPT-3 and similar large language models. Minds and Machines, 32(2), 341–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-022-09602-0

- Vishnevetsky J., Walters C. B., Tan K. S. (2018). Interrater reliability of the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT). Patient Education and Counseling, 101(3), 490–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.09.003

- Walker H. L., Ghani S., Kuemmerli C., Nebiker C. A., Müller B. P., Raptis D. A., Staubli S. M. (2023). Reliability of medical information provided by ChatGPT: Assessment against clinical guidelines and patient information quality instrument. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, e47479–e47479. https://doi.org/10.2196/47479

- Woolcott Research. (2014). Research report campaign developmental research for breast screening, prepared for: Australian government department of health. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/01/breastscreen-australia-campaign-developmental-research-for-breast-screening.pdf