We used an experimental paradigm to examine the extent to which e-cigarette product marketing influences attitudes towards e-cigarettes and susceptibility to use among young Australians who have never smoked cigarettes.

Certain product characteristics were associated with favourable attitudes and greater susceptibility to use.

Results suggest e-cigarette marketing in the form of product flavour, device type, and device colour may influence attitudes and behavioural intentions among young people who have never smoked.

Findings support the implementation of comprehensive flavour bans that include menthol and mint. Support is also provided for the introduction of standardized devices and bans on disposable e-cigarettes.

INTRODUCTION

A significant increase in the use of e-cigarettes has been observed globally over the last decade (). These products have been found to contain numerous toxicants that can be harmful to health (, ), and there is considerable evidence documenting the association between e-cigarette use and short-term health risks (, , , , , ). Evidence of long-term harm is limited, although data suggest e-cigarette use may increase the risk of respiratory disease (). These health risks differ based on the population under investigation. For example, there is evidence to suggest that e-cigarette use may be beneficial to those who smoke, provided they use the devices to completely and promptly quit smoking (). By contrast, among those who do not smoke, there is strong and conclusive evidence that e-cigarettes can be harmful to health (). It is this subgroup of the population and—more specifically—young people, that is of interest to the present study given the rapid and substantial increases in e-cigarette use that have been observed among adolescents and young adults, a group for which e-cigarette uptake has no benefits and many harms.

Initially a highly fragmented market dominated by independent companies, the e-cigarette market observed significant investment from transnational tobacco companies in 2012/2013 (). These companies now develop their own e-cigarettes and use a range of strategies to ‘aggressively’ market these products (, p. 222), with these strategies leveraging each of the four Ps of marketing—product, place, promotion, and price (). With respect to product, tobacco and e-cigarette companies target youth via the development of youth oriented (i) e-liquid flavours, (ii) e-liquid and e-cigarette packaging, and (iii) product innovations. For example, e-liquids are available in thousands of flavours (), many of which are highly appealing to youth and serve to attenuate nicotine’s aversive taste attributes, increasing product palatability (, ). A substantial minority of e-liquid labels and packaging feature cartoons (), and e-cigarette products are made to resemble USB drives, asthma inhalers, pens, and hoodie drawstrings, promoting stealth vaping ().

In terms of place, youth are targeted via social media platforms such as TikTok, Snapchat, and Instagram (, ). Social influencers with thousands of adolescent followers serve as brand ambassadors, with few disclosing sponsorship arrangements (). With respect to promotion, e-cigarette advertising often features very young, attractive protagonists and ‘cute’, ‘cool’, and ‘edgy’ imagery (). Promotional material also focuses on (i) e-liquids tasting good and providing pleasurable physical or emotional effects and (ii) the innovative nature of e-cigarette devices (, ). Finally, in terms of price, e-cigarettes are frequently advertised with offers such as coupons, discounts, and free giveaways ().

The tobacco and e-cigarette industries’ use of marketing tactics that target young people in order to establish a new generation of nicotine consumers is not new, with the strategies being adopted to sell e-cigarettes replicating those that have been used to increase sales of tobacco cigarettes for decades (). There is considerable evidence indicating that exposure to tobacco advertising and promotion increases the likelihood of smoking initiation and tobacco consumption (e.g. , ). In light of this evidence, Article 13 of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control recommends a comprehensive ban on all forms of tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship. Such bans have become a cornerstone of effective tobacco control laws (), reducing tobacco consumption globally (, ). However, the emergence of e-cigarettes has created new challenges, with these products providing tobacco and e-cigarette companies with an opportunity to circumvent policies banning tobacco advertising. Regulatory authorities are playing ‘catch-up’, and as countries attempt to bring e-cigarettes under regulatory frameworks, the industry has had ample time to market their products ().

Although product-based marketing is likely to be a major contributor to the rapid and substantial increase in youth e-cigarette use (, ), most studies conducted to date have focused on the impact of promotion. Results from these studies suggest that exposure to e-cigarette advertising is associated with lower harm perceptions, greater intentions to use e-cigarettes, and greater actual use of the devices among youth (, , , , , ). Work on product-based marketing is less extensive and has typically focused on e-cigarette flavourings. This research has found that compared to tobacco flavours, fruit, confectionary, dessert, and menthol flavours are associated with greater interest in trying or willingness to try e-cigarettes, as well as greater curiosity about the products (, , , ). These flavours are also preferred over tobacco flavours (, , , , , ), are considered more appealing than tobacco flavours (), and are perceived to be less harmful or dangerous than tobacco flavours (, , , ).

Research exploring perceptions of e-cigarette packaging and device shape is limited. In a qualitative study (), packaging colour was found to be a primary factor influencing decisions to purchase e-cigarette products. Other work has found that coloured packaging is considered appealing () and increases intentions to use e-cigarettes (). By contrast, dull packaging is believed to make e-cigarettes less appealing, especially to youth (). In experiments examining perceptions of e-cigarette packs that were digitally altered to remove brand imagery and colour, participants were less likely to report an interest in trying e-cigarettes in dull green packaging than in branded packaging (, ). In an experiment exploring the impact of device colour (i.e. ‘skin’ colour), females were more interested in trying devices in pink and pastel colours than males (). In terms of device shape, small pack sizes (such as those used for disposable products) have been described by youth as being similar to other products that appeal to young people (). Work by suggests compact devices that look like cigarettes are preferred by young adults. By contrast, observed that curiosity about tank and pod-based e-cigarettes is greater than curiosity about cigarette-like e-cigarettes.

There are two key gaps in the literature. First, although there appears to be consistent experimental evidence demonstrating the appeal of flavoured e-cigarettes among young people, the vast majority of these studies was conducted in the United States, a country with liberal regulations on the sale, use, and advertising of e-cigarette products. Whether these results hold in countries with greater restrictions has not been determined. Second, few experimental studies have examined the impact of device type and colour (). Accordingly, the present study aimed to examine the extent to which e-cigarette marketing in the form of product flavour, device type, and device colour influences attitudes towards e-cigarettes and susceptibility to use among adolescents and young adults who have never smoked tobacco cigarettes. As noted, this subgroup of the population was of specific interest as e-cigarette uptake among members of this cohort has no benefits and many harms ().

The context of this study is Australia, where legal access to e-cigarettes occurs only through pharmacies (). The Australian Federal Government has also implemented restrictions on product-based marketing, with a prohibition on all flavours except tobacco, menthol, or mint taking effect on the 1 March 2024. Plain packaging requirements were introduced on the 1 July 2025. Research investigating the extent to which various characteristics of e-cigarettes influence attitudes towards the products and susceptibility to use is thus critical to informing ongoing policy-related control efforts.

METHOD

Recruitment and procedure

As part of a larger project examining the impact of e-cigarette marketing, a sample of Australians aged 12–29 years who had never smoked tobacco cigarettes was recruited by an ISO-accredited web panel provider (Pureprofile) to participate in a national online survey with embedded experiments. Quotas were established to ensure the project sample comprised approximately equal proportions of men and women and was representative of the population in terms of socio-economic status. Pureprofile was instructed to oversample 12- to 17-year-olds given concerns about e-cigarette use among adolescents (). This study was approved by a human research ethics committee (The University of Melbourne, #27590) and all participants provided written informed consent. For those aged <16 years, consent was also sought from a guardian. Consent from a guardian was not sought for those aged 16 and 17 years as they were considered to have the capacity to consent on their own. Pureprofile monitored all responses for quality and automatically terminated the experiment if a participant failed more than one of the three built-in attention and logic checks.

Upon entering the online survey, participants were asked to provide their age, with those < 12 years and > 29 years excluded from participating any further. Those who were within this age range were randomly allocated to one condition across three experiments (between-subjects design): ‘flavour’, ‘device type’, and ‘device colour’.

Experiment 1: flavour

The flavour experiment featured five conditions. For each condition, participants were presented with a description of e-cigarettes. The descriptions were identical across conditions, except for the flavours being described. Condition 1 described fruit flavours (e.g. strawberry, grape, watermelon, and apple), Condition 2 described menthol/mint flavours (e.g. menthol, mint, and peppermint), Condition 3 described tobacco flavour, and Condition 4 described sweet flavours (e.g. glazed doughnut, vanilla custard, and gummy bears). The final condition, Condition 5, did not mention any flavourings. Each of these descriptions is presented in the Supplementary material.

Experiment 2: device type

The device type experiment featured three conditions. Across all conditions, participants were presented with an image of an e-cigarette that had been digitally manipulated to ensure all branding was removed. To minimize the influence of device colour, all devices were presented in greyscale/black. Participants allocated to Condition 1 were presented with a box mod device (i.e. a device that features an open tank that can be refilled with e-liquid), those in Condition 2 were presented with a pen-like device (i.e. a device similar to a box mod but with a distinctive pen shape), and those in Condition 3 were presented with a disposable device (i.e. a single-use product comprising both the device and e-liquid that cannot be reused or refilled). Given disposable products are the most commonly used e-cigarette devices among young Australians (, , ) and several popular brands exist on the Australian market, participants within Condition 3 were randomly allocated to view one of three disposable devices representing some of the most popular brands: ‘Puff Bar’, ‘HQD Cuvie’, and ‘IGET Bar’ (, ). Images of each device are presented in the Supplementary material.

Experiment 3: device colour (greyscale cf. purple)

The greyscale images presented in the device type condition were digitally manipulated to appear purple, a common vape colour. Participants allocated to Condition 1 were presented with a purple box mod device, those in Condition 2 were presented with a purple pen-like device, and those in Condition 3 were presented with a purple disposable device (either a Puff Bar, HQD Cuvie, or IGET Bar). Participants who viewed the greyscale/black images in Experiment 2 served as the comparison group for each of these conditions such that for each device type, responses to the coloured image were compared to responses to the greyscale/black image: (i) greyscale box mod cf. purple box mod, (ii) greyscale pen cf. purple pen, and (iii) greyscale disposable cf. purple disposable.

Measures

Dependent variables

The primary dependent variables included (i) overall opinion of the product described/shown, (ii) attitudes towards the product described/shown, and (iii) liking of the product described/shown. We also assessed curiosity to use the product described/shown, willingness to use the product described/shown, and intentions to use the product described/shown, which are extensively used measures of susceptibility to product use in the area of tobacco control (, , , ).

For overall opinion, participants were asked ‘How would you describe your overall opinion of this product?’ (1 = Very negative to 5 = Very positive; as per ). To assess attitudes, participants were presented with five 5-point semantic differential scales (as per ) and asked to report whether they believed the product to be ‘Unenjoyable/Enjoyable’, ‘Boring/Fun’, ‘Stupid/Smart’, ‘Uncool/Cool’, and ‘Unattractive/Attractive’. A grand mean comprising the semantic differential scales was computed after reliability analysis (α = 0.93). Product liking was assessed with the following item developed by the research team: ‘How much do you like the product being described/shown?’ (1 = Strongly dislike to 5 = Strongly like). Curiosity was assessed with the item ‘How curious are you about using the product?’ (as per ; response options: 1 = Definitely not to 4 = Definitely yes). Willingness to use the product was assessed with the item ‘Suppose you were with a group of friends and they offered you the product to try. How willing would you be to try the product?’ (as per ; 1 = Definitely not to 4 = Definitely yes). Finally, intentions were assessed with the item ‘Do you intend to use the product in the next 6 months?’ (as per ; response options: 1 = Definitely not to 4 = Definitely yes).

Demographics

Participants were asked to report their gender, age, postcode (used to calculate socio-economic status as per the ), tobacco cigarette use, and e-cigarette use. For tobacco cigarette use, participants were asked whether they had ever smoked a tobacco cigarette (even one or two puffs). Only those who had never smoked were of interest to the present study. For e-cigarette use, participants were asked whether they had ever used an e-cigarette (even one or two puffs), with those responding in the affirmative subsequently asked on how many days over the past 30 they used e-cigarettes that (i) contained nicotine, (ii) did not contain nicotine, and (iii) were flavoured (as per ). Responses were dichotomized as follows: 0 = never use, 1 = current or former use.

Statistical analysis

For each experiment, analyses were conducted to identify any differences between participants in each condition on the variables of gender, age, socio-economic status, and e-cigarette use. One-way ANOVAs were used to explore differences in terms of age, and chi-square analyses were used to explore differences for the categorical variables of gender, socio-economic status, and e-cigarette use. Only two differences were observed: (i) for the flavour experiment, the unflavoured condition comprised a greater proportion of those who had never used e-cigarettes compared to the menthol/mint condition (84% cf. 72%) and (ii) for the device colour experiment, the greyscale/black box mod condition comprised a greater proportion of participants residing in a low socio-economic status area compared to the purple box mod condition (41% cf. 26%).

Generalized linear models (GLM) were subsequently used to assess the effect of condition on each of the dependent variables within each experiment, with robust standard errors calculated to address any violations in homogeneity of variance. For each model, ‘Condition’ was entered as the primary independent variable. For models involving the flavour experiment, ‘E-cigarette use’ was entered as a control variable given the difference between condition samples that was observed in relation to this variable. For models assessing the impact of box mod device colour, ‘Socio-economic status’ was entered as a control variable; however, findings from these analyses did not differ from those conducted without controlling for socio-economic status. As such, we present results from the analysis exploring the impact of condition only, with results from analyses controlling for socio-economic status presented in the Supplementary material.

Where a significant main effect of condition was identified in output from the GLM, pairwise comparisons of estimated marginal means were used to explore the direction of this main effect. Bonferroni-adjusted P-values were calculated in SPSS to control for the familywise error rate (note: analyses were also conducted using the less conservative Sidak method but differences in results were not observed). Where a significant condition by e-cigarette use interaction was identified, we conducted follow-up analyses that examined the effect of condition on the relevant dependent variable for those who vape/vaped and those who had never vaped separately.

RESULTS

Sample

The recruited sample comprised 3157 participants. However, only those who had never smoked tobacco cigarettes (n = 1879) were of interest to the present study. The demographic profiles of participants in the overall sample and in each experimental condition are presented in Supplementary Tables S1 to S4.

Experiment 1: product flavour

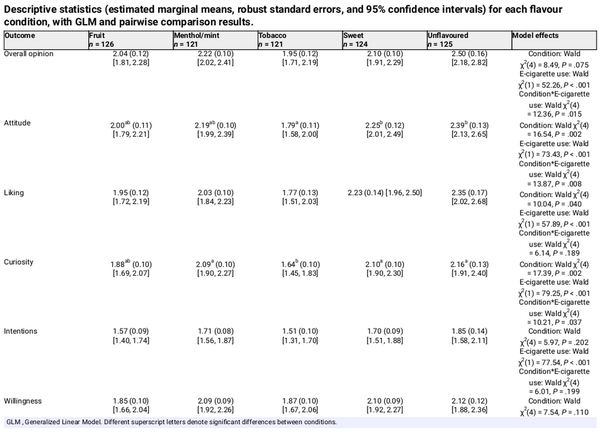

GLM results and estimated marginal means for each of the dependent variables across each of the flavour conditions are presented in Table 1. A significant main effect of condition was observed for the variables of attitude, liking, and curiosity, but not for overall opinion, willingness to use, or intentions to use. Significant condition by e-cigarette use interaction effects were observed for overall opinion, attitude, and curiosity, but not for product liking, willingness to use, or intentions to use.

For the main effects, results from pairwise comparisons of estimated marginal means indicate that those who were presented with a description of a tobacco-flavoured e-cigarette had significantly lower scores for attitude compared to those presented with a description of an unflavoured or sweet-flavoured e-cigarette. Those who were presented with a description of a tobacco-flavoured e-cigarette also had significantly lower scores for curiosity to use e-cigarettes compared to those presented with a description of an unflavoured, sweet-flavoured, or menthol/mint-flavoured e-cigarette. Pairwise comparisons exploring the significant main effect observed for product liking were not significant after Bonferroni correction.

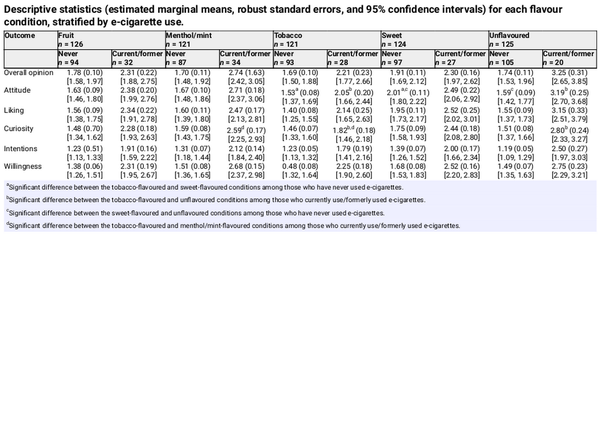

Given the presence of significant interaction effects for overall opinion, attitude, and curiosity, post hoc analyses were conducted to explore these results further (results presented in Table 2). For overall opinion, pairwise comparisons were not significant when stratifying by e-cigarette use, although results suggest the effect of condition was likely only present among those who currently use e-cigarettes or had used them in the past. For attitude, results indicated that the difference between the tobacco-flavoured (M = 2.05, SE = 0.20) and unflavoured (M = 3.19, SE = 0.25) conditions was only significant among those who currently use e-cigarettes or had used them in the past (Bonferroni P = .003), while the difference between the tobacco-flavoured (M = 1.53, SE = 0.08) and sweet-flavoured (M = 2.01, SE = 0.11) conditions was only significant among those who had never used e-cigarettes (Bonferroni P = .004). Results from the post hoc tests also indicated a significant difference between those in the sweet-flavoured condition (M = 2.01, SE = 0.11) and those in the unflavoured condition (M = 1.59, SE = 0.09) among those who had never used e-cigarettes (Bonferroni P = .026).

For curiosity, post hoc tests indicated that the difference between the tobacco-flavoured and menthol/mint-flavoured conditions (M = 1.82, SE = 0.18 cf. M = 2.59, SE = 0.17, Bonferroni P = .022) and the difference between the tobacco-flavoured and unflavoured conditions (M = 1.82, SE = 0.18 cf. M = 2.80, SE = 0.24, Bonferroni P = .012) was only significant for those who currently use e-cigarettes or had used them in the past. The difference identified between the tobacco-flavoured and sweet-flavoured conditions failed to reach significance when stratifying at the level of e-cigarette use.

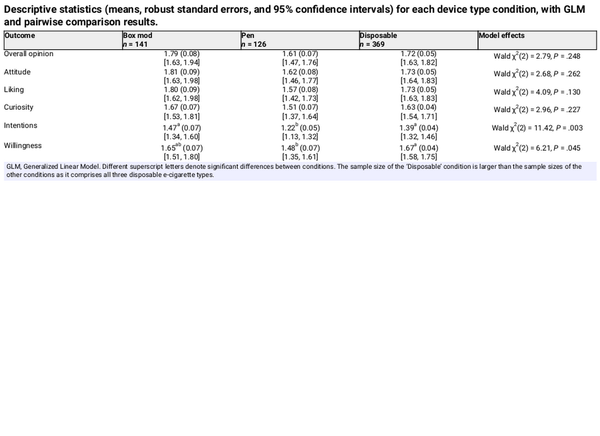

Experiment 2: device type

GLM results and estimated marginal means for each of the dependent variables across each of the device type conditions are presented in Table 3. A significant effect of condition was observed for intentions and willingness to use e-cigarettes. Those presented with a box mod device (P = .008) and those presented with a disposable device (P = .017) reported greater intentions to use the products in the next 6 months compared to those presented with a pen-like device. Those presented with a disposable device also reported greater willingness to use the product compared to those presented with a pen-like device (P = .044). For readers interested in results for each disposable e-cigarette brand, these are available in Supplementary Table S5.

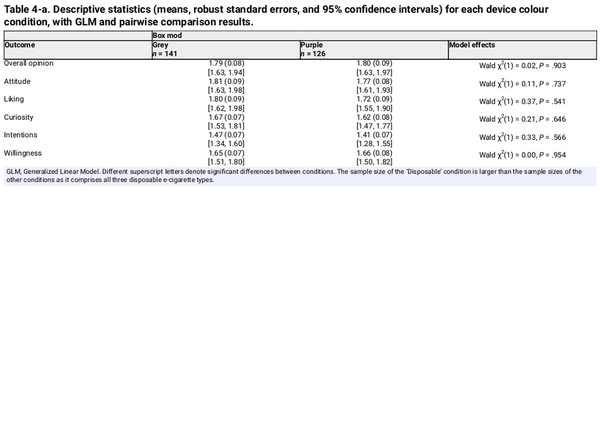

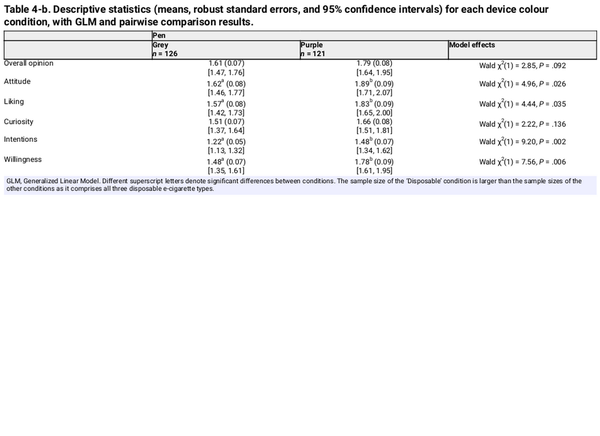

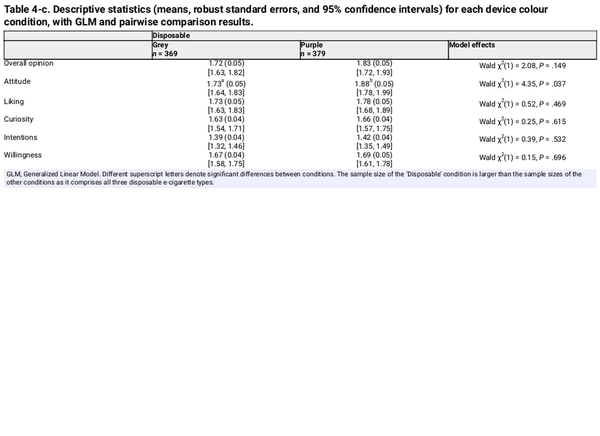

Experiment 3: device colour

GLM results and estimated marginal means for Experiment 3 are presented in Table 4. A significant effect of colour was observed within the pen-like device for attitude, product liking, intentions to use, and willingness to use. Compared to those presented with a greyscale/black pen-like device, those presented with a purple pen-like device held more favourable product attitudes (P = .026) and reported greater liking for the product (P = .035), intentions to use the product (P = .002), and willingness to use the product (P = .006). A significant effect of colour was also observed within the disposable product for attitude. Compared to those presented with a greyscale/black disposable device, those presented with a purple disposable device held more favourable product attitudes (P = .037). Results from analyses controlling for socio-economic status are presented in Supplementary Table S6.

DISCUSSION

While the strategies used by the e-cigarette industry to promote its products are well-documented (), research examining the impact of product-based marketing is limited and largely confined to the United States. We thus sought to determine the extent to which e-cigarette marketing in the form of product flavour, device type, and device colour influences attitudes and increases susceptibility to use among Australian adolescents and young adults who have never smoked. Overall, results suggest e-cigarette marketing in the form of product flavour, device type, and device colour may influence attitudes towards e-cigarettes and increase use susceptibility among young people who have never smoked, with some differences in the effect of flavour-based marketing observed between those who have never used e-cigarettes and those who currently use e-cigarettes or had used e-cigarettes in the past.

Product flavour

Results from the flavour experiment support the outcomes of previous discrete choice experiments that have demonstrated adolescents’ and young adults’ preferences for and willingness to try flavoured e-cigarette products (, , , , ). In the present study, those shown a description of a sweet-flavoured e-cigarette held more favourable attitudes towards the product and expressed greater curiosity about using the product compared to those shown a description of a tobacco-flavoured product. In terms of attitudes, this finding was observed only among those who had never used e-cigarettes, with this group of participants also holding a more positive attitude towards sweet-flavoured e-cigarettes than unflavoured e-cigarettes. These findings suggest that the availability of sweet-flavoured e-cigarettes may contribute to positive product perceptions, especially among those who have never used the product. Of further note in relation to the flavour experiment is the finding that among those who currently use e-cigarettes or had used e-cigarettes in the past, curiosity to use menthol/mint-flavoured e-cigarettes was significantly higher than curiosity to use tobacco-flavoured e-cigarettes.

These findings provide support for the implementation of legislation that prohibits e-cigarette flavourings. Such legislation has already been introduced in countries such as Australia, Finland, China, and the Netherlands but could be improved, with some jurisdictions—including Australia—allowing e-cigarettes to be made available in menthol and mint flavours. To reduce the appeal of e-cigarettes among young people, encourage cessation, and reduce prevalence rates, the introduction of comprehensive flavour bans that include menthol and mint flavours is recommended. A comprehensive ban is important for several reasons. First, the tobacco industry has long used flavours in tobacco products as a marketing strategy to target young people (, ), with flavourings serving to attenuate nicotine’s aversive taste attributes, reduce harm perceptions, and increase product demand (, , ). Legislation that prohibits e-cigarette flavourings thus has the potential to stymie industry marketing activity.

Second, evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) work suggests that advertising for sweet- or fruit-flavoured e-cigarettes is more likely than advertising for tobacco-flavoured e-cigarettes to interfere with the neural processing of health warnings (). With governments around the world introducing health warnings on e-cigarette products, these fMRI findings suggest that the effectiveness of this control measure may be reduced if restrictions on the availability of flavourings are not implemented concurrently. Legislation that prohibits e-cigarette flavourings thus offers the potential to increase health warning effectiveness. Finally, there is no clear association between the use of e-cigarette flavours and smoking cessation (, ). In addition, research suggests that (i) among e-cigarette consumers who smoke or smoked in the past, there is little preference for menthol or other flavours compared to tobacco flavours () and (ii) banning menthol in both cigarettes and e-cigarettes is likely to result in the greatest reduction in overall use of both products (). The introduction of a comprehensive flavour ban thus constitutes a potential means of protecting those who have never smoked without detrimentally impacting those seeking to use e-cigarettes to quit smoking.

Device type

In terms of device type, greater susceptibility to product use was observed among those presented with a disposable device relative to those presented with a pen-like device. These results are consistent with prior work that has observed a preference for disposable e-cigarettes among Australian adolescents and young adults (, ). Results are also consistent with recent research from England, which compared vaping prevalence before and after the emergence of disposable e-cigarettes and observed a substantial increase in vaping-related behaviours since such products were introduced to the market, especially among young people (). Overall, findings provide support for bans on disposable (i.e. single use) e-cigarettes as a means of reducing product appeal, which some jurisdictions have implemented (e.g. Australia) or will be implementing (e.g. the United Kingdom).

Of additional interest in relation to device type is the finding that greater susceptibility to product use was observed among those presented with a box mod device relative to those presented with a pen-like device. Further work exploring the impact of device type is warranted, especially as the industry responds to bans on single use products by developing appealing non-disposable devices, such as ‘smart vapes’ featuring video games and interactive displays (). Pen-like products do not have the surface area to allow for ‘smart’ features, which may explain the preference in the present study for the larger box mod device that does have the surface area for such features.

Device colour

In terms of device colour, results were somewhat mixed. This feature influenced attitudes towards the pen-like and disposable devices and influenced product liking and use susceptibility for the pen-like device, but did not influence outcomes for the box mod device. This suggests a possible interaction between device type and colour. Although this could not be examined in the present study due to variable non-independence (i.e. data from the device type experiment also served as the data for the greyscale/black conditions in the device colour experiment), support for a possible interaction effect comes from qualitative work by , which found that young people link brightly coloured packaging with disposable products.

Findings relating to device colour are consistent with prior work on e-cigarette product packaging that identified colour as a primary factor influencing decisions to purchase e-cigarette products (). Young people consider brightly coloured packaging to be appealing (, ), and such packaging has been linked with use susceptibility (). We extend this work by identifying a potential impact of device colour on attitudes and susceptibility to use. This is an important finding that suggests device colour should also be considered in ‘plain packaging’ or ‘standardized packaging’ regulations that seek to make e-cigarette products less appealing. E-cigarette packaging is typically discarded after a device is purchased (). As a result, the device itself has greater visibility than the packaging in which it came (). The introduction of regulations that mandate standardized devices and prohibit colour, images, and other promotional characteristics on device ‘skins’ is thus recommended as an important complementary measure to standardized packaging that has the potential to further reduce the appeal of e-cigarette products.

Limitations

This study had some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, to minimize the overall sample size required for the study, data from the device type experiment also served as the data for the greyscale/black conditions in the device colour experiment. This precluded us from conducting a posteriori analyses assessing a possible device type by device colour interaction effect. Further investigation with independence across experiments is needed to test for this interaction. We also recommend research that explores the possibility of a 3-way interaction between device flavour, device type, and device colour given colour may be a marker for both flavour and product type (). Second, we assessed behavioural intentions rather than actual behaviour. Future research could consider assessing the impact of e-cigarette flavour, type, and colour on actual e-cigarette use. Third, some post hoc tests failed to reach significance despite a significant effect being observed at the overall level. This was particularly the case for tests that required stratification by e-cigarette use and featured an adjustment for multiple comparisons. We thus recommend replication with a larger sample size. Finally, to ensure our experiment was internally valid, each feature of an e-cigarette product was isolated for examination, limiting ecological validity. We acknowledge that consumer decision-making likely involves a whole-of-product judgement. However, as governments around the world introduce measures to address vaping among youth, results that isolate the effect of individual e-cigarette features can inform regulatory efforts as they provide data on which specific elements of a product should be targeted.

CONCLUSION

Results from the present experimental study suggest e-cigarette marketing in the form of product flavour, device type, and device colour may influence attitudes towards e-cigarettes and increase susceptibility to use among adolescents and young adults who have never smoked. Findings support the implementation of comprehensive flavour bans that include menthol and mint. Support is also provided for the introduction of standardized devices and bans on disposable e-cigarettes.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Professor Sarah Durkin for her advice on stimuli development.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2021. Canberra: ABS, 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/socio-economic-indexes-areas-seifa-australia/2021

- Baker AN, Wilson SJ, Hayes JE. Flavor and product messaging are the two most important drivers of electronic cigarette selection in a choice-based task. Sci Rep 2021;11:4689. 10.1038/s41598-021-84332-4

- Banks E, Yazidjoglou A, Brown S, et al Electronic Cigarettes and Health Outcomes: Systematic Review of Global Evidence. Canberra: National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, 2022. https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/262914

- Banks E, Yazidjoglou A, Brown S, et al Electronic cigarettes and health outcomes: umbrella and systematic review of the global evidence. Med J Aust 2023;218:267–75. 10.5694/mja2.51890

- Blecher E. The impact of tobacco advertising bans on consumption in developing countries. J Health Econ 2008;27:930–42. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.02.010

- Buckell J, Marti J, Sindelar JL. Should flavours be banned in cigarettes and e-cigarettes? Evidence on adult smokers and recent quitters from a discrete choice experiment. Tob Control 2019;28:168–75. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-054165

- Buckell J, Sindelar JL. The impact of flavors, health risks, secondhand smoke and prices on young adults’ cigarette and e-cigarette choices: a discrete choice experiment. Addiction 2019;114:1427–35. 10.1111/add.14610

- Camenga D, Gutierrez KM, Kong G, et al E-cigarette advertising exposure in e-cigarette naïve adolescents and subsequent e-cigarette use: a longitudinal cohort study. Addict Behav 2018;81:78–83. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.02.008

- Caporale A, Langham MC, Guo W, et al Acute effects of electronic cigarette aerosol inhalation on vascular function detected at quantitative MRI. Radiology 2019;293:97–106. 10.1148/radiol.2019190562

- Carey FR, Rogers SM, Cohn EA, et al Understanding susceptibility to e-cigarettes: a comprehensive model of risk factors that influence the transition from non-susceptible to susceptible among e-cigarette naïve adolescents. Addict Behav 2019;91:68–74. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.09.002

- Carpenter CM, Wayne GF, Pauly JL, et al New cigarette brands with flavors that appeal to youth: tobacco marketing strategies. Health Aff 2005;24:1601–10. 10.1377/hlthaff.24.6.1601

- Chaffee B, Couch E, Urata J, et al Electronic cigarette and moist snuff product characteristics independently associated with youth tobacco product perceptions. Tob Induc Dis 2020;18:71. 10.18332/tid/125513

- Chaffee BW, Couch ET, Wilkinson ML, et al Flavors increase adolescents’ willingness to try nicotine and cannabis vape products. Drug Alcohol Depend 2023;246:109834. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2023.109834

- Chen-Sankey JC, Unger JB, Bansal-Travers M, et al E-cigarette marketing exposure and subsequent experimentation among youth and young adults. Pediatrics 2019;144:e20191119. 10.1542/peds.2019-1119

- Cohn AM, Johnson AL, Abudayyeh H, et al Pack modifications influence perceptions of menthol e-cigarettes. Tob Regul Sci 2021;7:87–102. 10.18001/TRS.7.2.1

- Connolly G. Sweet and spicy flavours: new brands for minorities and youth. Tob Control 2004;13:211–2. 10.1136/tc.2004.009191

- Czoli CD, Goniewicz M, Islam T, et al Consumer preferences for electronic cigarettes: results from a discrete choice experiment. Tob Control 2016;25:e30. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052422

- Durkin K, Williford DN, Turiano NA, et al Associations between peer use, costs and benefits, self-efficacy, and adolescent e-cigarette use. J Pediatr Psychol 2021;46:112–22. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa097

- El-Hellani A, Al-Moussawi S, El-Hage R, et al Carbon monoxide and small hydrocarbon emissions from sub-Ohm electronic cigarettes. Chem Res Toxicol 2019;32:312–7. 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.8b00324

- Farrelly MC, Duke JC, Crankshaw EC, et al A randomized trial of the effect of e-cigarette TV advertisements on intentions to use e-cigarettes. Am J Prev Med 2015;49:686–93. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.010

- Ford A, MacKintosh AM, Bauld L, et al Adolescents’ responses to the promotion and flavouring of e-cigarettes. Int J Public Health 2016;61:215–24. 10.1007/s00038-015-0769-5

- Freeman B, Watts C, Astuti PAS. Global tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship regulation: what’s old, what’s new and where to next? Tob Control 2022;31:216–21. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056551

- Garrison KA, O'Malley SS, Gueorguieva R, et al A fMRI study on the impact of advertising for flavored e-cigarettes on susceptible young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend 2018;186:233–41. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.01.026

- Gomes MN, Reid JL, Hammond D. The effect of branded versus standardized e-cigarette packaging and device designs: an experimental study of youth interest in vaping products. Public Health 2024;230:223–30. 10.1016/j.puhe.2024.02.001

- Greenhalgh EM, Jenkins S, Bain E, et al Advertising and promotion of e-cigarettes. In: Greenhalgh EM, Scollo MM, Winstanley MH (eds.), Tobacco in Australia: Facts and Issues. Cancer Council Victoria, 2025. https://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-18-e-cigarettes/18-2-advertising-and-promotion

- Hammond D, East K, Wiggers D, et al Vaping products in Canada: A market scan of industry product, labelling and packaging promotional practices. 2020. https://davidhammond.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/2020-Vaping-Packaging-Final-Report-Hammond-Dec-15.pdf (11 April 2025, date last accessed)

- Hsu G, Sun JY, Zhu SH. Evolution of electronic cigarette brands from 2013–2014 to 2016–2017: analysis of brand websites. J Med Internet Res 2018;20:e80. 10.2196/jmir.8550

- Huang LL, Baker HM, Meernik C, et al Impact of non-menthol flavours in tobacco products on perceptions and use among youth, young adults and adults: a systematic review. Tob Control 2017;26:709–19. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053196

- Jenkins C, Powrie F, Kelso C, et al Chemical analysis and flavor distribution of electronic cigarettes in Australian schools. Nicotine Tob Res 2024a;27:997–1005. 10.1093/ntr/ntae262

- Jenkins C, Powrie F, Morgan J, et al Labelling and composition of contraband electronic cigarettes: analysis of products from Australia. Int J Drug Policy 2024b;128:104466. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2024.104466

- Jerzyński T, Stimson GV. Estimation of the global number of vapers: 82 million worldwide in 2021. Drugs Habits Soc Policy 2023;24:91–103. 10.1108/DHS-07-2022-0028

- Jones D, Morgan A, Moodie C, et al The role of e-cigarette packaging as a health communications tool: a focus group study with adolescents and adults in England and Scotland. Nicotine Tob Res 2024;27:705–13. 10.1093/ntr/ntae107

- Jongenelis MI. E-cigarette product preferences of Australian adolescent and adult users: a 2022 study. BMC Public Health 2023;23:220. 10.1186/s12889-023-15142-8

- Jongenelis MI, Thoonen KAHJ. Factors associated with susceptibility to e-cigarette use among Australian adolescents. Int J Drug Policy 2023;122:104249. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2023.104249

- Katz SJ, Shi W, Erkkinen M, et al High school youth and e-cigarettes: the influence of modified risk statements and flavors on e-cigarette packaging. Am J Health Behav 2020;44:130–45. 10.5993/ajhb.44.2.2

- Kennedy CD, van Schalkwyk MC, McKee M, et al The cardiovascular effects of electronic cigarettes: a systematic review of experimental studies. Prev Med 2019;127:105770. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105770

- Kim H, Lim J, Buehler SS, et al Role of sweet and other flavours in liking and disliking of electronic cigarettes. Tob Control 2016;25:55–61. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053221

- Kintz N, Liu M, Chou CP, et al Risk factors associated with subsequent initiation of cigarettes and e-cigarettes in adolescence: a structural equation modeling approach. Drug Alcohol Depend 2020;207:107676. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107676

- Kuntic M, Oelze M, Steven S, et al Short-term e-cigarette vapour exposure causes vascular oxidative stress and dysfunction: evidence for a close connection to brain damage and a key role of the phagocytic NADPH oxidase (NOX-2). Eur Heart J 2020;41:2472–83. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz772

- Laestadius LI, Wahl MM, Pokhrel P, et al From apple to werewolf: a content analysis of marketing for e-liquids on Instagram. Addict Behav 2019;91:119–27. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.09.008

- Leventhal A, Cho J, Barrington-Trimis J, et al Sensory attributes of e-cigarette flavours and nicotine as mediators of interproduct differences in appeal among young adults. Tob Control 2020;29:679–86. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055172

- Liber AC, Knoll M, Cadham CJ, et al The role of flavored electronic nicotine delivery systems in smoking cessation: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend Rep 2023;7:100143. 10.1016/j.dadr.2023.100143

- Lindson N, Livingstone-Banks J, Butler AR, et al An update of a systematic review and meta-analyses exploring flavours in intervention studies of e-cigarettes for smoking cessation. Addiction 2025;120:770–8. 10.1111/add.16736

- Ling PM, Kim M, Egbe CO, et al Moving targets: how the rapidly changing tobacco and nicotine landscape creates advertising and promotion policy challenges. Tob Control 2022;31:222–8. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056552

- Lovato C, Watts A, Stead LF. Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviours. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;2011:CD003439. 10.1002/14651858.CD003439.pub2

- Lyu JC, Huang P, Jiang N, et al A systematic review of e-cigarette marketing communication: messages, communication channels, and strategies. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:9263. 10.3390/ijerph19159263

- Ma S, Jiang S, Ling M, et al Price promotions of e-liquid products sold in online stores. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:8870. 10.3390/ijerph19148870

- McCarthy EJ. Basic Marketing: A Managerial Approach. R.D. Irwin, 1960.

- Meo SA, Ansary MA, Barayan FR, et al Electronic cigarettes: impact on lung function and fractional exhaled nitric oxide among healthy adults. Am J Mens Health 2019;13:1557988318806073. 10.1177/1557988318806073

- Monzón J, Islam F, Mus S, et al Effects of tobacco product type and characteristics on appeal and perceived harm: results from a discrete choice experiment among Guatemalan adolescents. Prev Med 2021;148:106590. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106590

- Moodie C, Jones D, Angus K, et al Improving our Understanding of e-Cigarette and Refill Packaging in the UK: how is it Used for Product Promotion and Perceived by Consumers, to What Extent Does it Comply with Product Regulations, and Could it be Used to Better Protect Consumers? United Kingdom: Cancer Research UK, 2023. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/sites/default/files/moodie_et_al._2023_improving_our_understanding_of_e-cigarette_and_refill_packaging_in_the_uk.pdf

- National Health and Medical Research Council. 2022 CEO Statement on Electronic Cigarettes. Australia: NHMRC, 2022. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/health-advice/all-topics/electronic-cigarettes/ceo-statement

- Pettigrew S, Miller M, Santos JA, et al E-cigarette attitudes and use in a sample of Australians aged 15–30 years. Aust N Z J Public Health 2023a;47:100035. 10.1016/j.anzjph.2023.100035

- Pettigrew S, Santos JA, Li Y, et al Factors contributing to young people’s susceptibility to e-cigarettes in four countries. Drug Alcohol Depend 2023b;250:109944. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2023.109944

- Pu J, Zhang X. Exposure to advertising and perception, interest, and use of e-cigarettes among adolescents: findings from the US national youth tobacco survey. Perspect Public Health 2017;137:322–5. 10.1177/1757913917703151

- Ramamurthi D, Chau C, Jackler RK. JUUL and other stealth vaporisers: hiding the habit from parents and teachers. Tob Control 2019;28:610–6. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054455

- Reinhold B, Fischbein R, Bhamidipalli SS, et al Associations of attitudes towards electronic cigarettes with advertisement exposure and social determinants: a cross sectional study. Tob Induc Dis 2017;15:13. 10.1186/s12971-017-0118-y

- Ruprecht AA, De Marco C, Saffari A, et al Environmental pollution and emission factors of electronic cigarettes, heat-not-burn tobacco products, and conventional cigarettes. Aerosol Sci Technol 2017;51:674–84. 10.1080/02786826.2017.1300231

- Saffer H, Chaloupka F. The effect of tobacco advertising bans on tobacco consumption. J Health Econ 2000;19:1117–37. 10.1016/S0167-6296(00)00054-0

- Seitz CM, Orsini MM, Jung G, et al Cartoon images on e-juice labels: a descriptive analysis. Nicotine Tob Res 2020;22:1909–11. 10.1093/ntr/ntaa029

- Shang C, Huang J, Chaloupka FJ, et al The impact of flavour, device type and warning messages on youth preferences for electronic nicotine delivery systems: evidence from an online discrete choice experiment. Tob Control 2018;27:e152–9. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053754

- Sharma A, McCausland K, Jancey J. Adolescents’ health perceptions of e-cigarettes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2021;60:716–25. 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.12.013

- Silveira ML, Conway KP, Everard CD, et al Longitudinal associations between susceptibility to tobacco use and the onset of other substances among US youth. Prev Med 2020;135:106074 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106074

- Skotsimara G, Antonopoulos AS, Oikonomou E, et al Cardiovascular effects of electronic cigarettes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2019;26:1219–28. 10.1177/2047487319832975

- Sowles SJ, Krauss MJ, Connolly S, et al A content analysis of vaping advertisements on twitter, November 2014. Prev Chronic Dis 2016;13:E139. 10.5888/pcd13.160274

- Stanton CA, Bansal-Travers M, Johnson AL, et al Longitudinal e-cigarette and cigarette use among US youth in the PATH study (2013–2015). J Natl Cancer Inst 2019;111:1088–96. 10.1093/jnci/djz006

- Struik LL, Dow-Fleisner S, Belliveau M, et al Tactics for drawing youth to vaping: content analysis of electronic cigarette advertisements. J Med Internet Res 2020;22:e18943. 10.2196/18943

- Sun T, Lim CC, Chung J, et al Vaping on TikTok: a systematic thematic analysis. Tob Control 2023;32:251–4. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056619

- Tattan-Birch H, Brown J, Shahab L, et al Trends in vaping and smoking following the rise of disposable e-cigarettes: a repeat cross-sectional study in England between 2016 and 2023. Lancet Reg Health–Eur 2024;42:100924. 10.1016/j.lanepe.2024.100924

- Taylor E, Arnott D, Cheeseman H, et al Association of fully branded and standardized e-cigarette packaging with interest in trying products among youths and adults in Great Britain. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6:e231799–231799. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.1799

- Therapeutic Goods Administration. Vaping hub. Canberra: Australia Government, Department of Health and Aged Care, 2024. https://www.tga.gov.au/products/unapproved-therapeutic-goods/vaping-hub#:∼:text=All vapes containing nicotine are,to customers with a prescription

- Tobacco Tactics. E-cigarettes. The University of Bath, 2023. https://www.tobaccotactics.org/article/e-cigarettes/

- Vassey J, Valente T, Barker J, et al E-cigarette brands and social media influencers on Instagram: a social network analysis. Tob Control 2023;32:e184–91. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-057053

- Watts C, Egger S, Dessaix A, et al Vaping product access and use among 14–17-year-olds in New South Wales: a cross-sectional study. Aust N Z J Public Health 2022;46:814–20. 10.1111/1753-6405.13316

- Watts C, Rose S, McGill B, et al New image, same tactics: global tobacco and vaping industry strategies to promote youth vaping. Health Promot Int 2024;39:daae126. 10.1093/heapro/daae126

- Wills TA, Pagano I, Williams RJ, et al E-cigarette use and respiratory disorder in an adult sample. Drug Alcohol Depend 2019;194:363–70. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.10.004

- Wong M, Talbot P. Pac-Man on a vape: electronic cigarettes that target youth as handheld multimedia and gaming devices. Tob Control 2024:tc-2024-058794. 10.1136/tc-2024-058794

- Yang Y, Lindblom EN, Salloum RG, et al Impact of flavours, device, nicotine levels and price on adult e-cigarette users’ tobacco and nicotine product choices. Tob Control 2023;32:e23–30. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056599

- Zare S, Nemati M, Zheng Y. A systematic review of consumer preference for e-cigarette attributes: flavor, nicotine strength, and type. PLoS One 2018;13:e0194145. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194145