Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by social-communication impairments and restricted, repetitive behaviors, and interests (RRBI) (). Considering the fact that social difficulty is a primary facet of ASD, there is relatively little work directly examining prosocial behaviors in this population (). It is reasonable to assume that children with ASD display fewer prosocial behaviors in comparison to typically developing (TD) children, due to the social challenge inherent in an ASD diagnosis. Studies supporting this assumption, however, rely mainly on parental reports (; ). Yet, some empirical studies found no difference in prosocial behaviors between children with ASD and controls. For example, found that prosocial behavior in response to distress signals of a peer in a computer task was similar in 6–7-year-old children with and without ASD (see also ). While the prosocial behavior measured in these studies was a response to another person’s distress, parents’ reports of prosocial behaviors usually cover a broader set of circumstances (though filtered through the parents’ perspective). Thus, in some contexts, children with ASD may display greater prosocial behavior than expected, considering the social difficulties associated with their diagnosis. Sibling interactions may be such a context. Interaction with siblings has been shown to be an important environment for social development in TD children (; ).

In a retrospective study, reported that children with ASD who have TD siblings gained better social functioning scores than children with ASD who grow up as only children in their families. This effect was even greater when TD siblings were older (mean age of 4 years old; ). , p. 928) speculated that the benefit of having older siblings on the social functioning of children with ASD could be explained either by parental factors (e.g., more experienced parenting, reduced parental stress) or by the fact that “older TD siblings function as a role model for their younger sibling with ASD, take a lead in the relationship and enable participation in social interactions such as play and discourse”. The present study was designed to explore the TD sibling as a role model for children with ASD by characterizing siblings’ naturally occurring interactions in a home environment, with a focus on prosocial behaviors.

Studies that directly examined sibling interaction in families of children with ASD are rare (for exceptions, see ; ; , ). ) investigated 22 sibling dyads involving a child with ASD (3–15 years old) and his/her infant sibling (i.e., an infant at high risk for ASD, aged 17–20 months), in comparison to 29 TD siblings dyads (older siblings 3–8 years old, and younger ones 17–19 months). There were no between-group differences in positive behaviors (, define positive behaviors as prosocial, e.g., sharing a toy, as “allowing the other sibling to do something” [p. 7], and as positive responses to the other sibling’s behaviors). However, sibling dyads involving an older sibling with ASD had higher levels of negative behaviors in comparison to pairs of TD sibling dyads. examined the interactions of 15 ASD children (3–10 years old) and their younger or older TD siblings (1–12 years old) in comparison to sibling pairs in which one of the siblings has Down syndrome (DS), and reexamined six of these dyads 12 months later (). Knott and colleagues found that during the interaction with their TD siblings, younger siblings with ASD showed fewer prosocial initiations in comparison to younger siblings with DS. At the same time, Knott and colleagues emphasized that the children with ASD demonstrated better social skills than might have been predicted based on existing literature. compared the play interactions of nine children with ASD (3–7 years old) and their siblings (eight older siblings and one younger sibling) to the interactions of the same children and their parents. Although parents exhibited more play behaviors toward the children with ASD than the siblings did, children with ASD initiated more interactions with their siblings than with their parents.

These earlier studies either did not directly examine prosocial behaviors or did not use a younger ASD/older TD sibling dyad design. Therefore, it is hard to learn from them about the “TD sibling as a role model” hypothesis in the context of prosocial behaviors. Nevertheless, these studies reflect that comparing ASD/TD sibling dyads to dyads of siblings with no ASD highlights the social deficits in the ASD/TD siblings’ dyadic interaction. Yet, comparing the interaction of the same child with ASD with different social partners in the family highlights the unique social role of sibling interaction.

In the current study, we aimed to microanalyze siblings’ interactions to detect characteristics related to the “TD sibling as a role model” hypothesis. Taking “the lead” in the interaction on the part of the older sibling, as , p. 928) describe, can be demonstrated by conducting more play-related behaviors, such as setting rules and roles, and initiating more discourse, agonistic (e.g., insulting and threatening), and prosocial (e.g., helping, sharing, and comforting; ) behaviors. Nevertheless, the dominancy of the older sibling is not sufficient without the following and imitating on the part of the younger sibling. This role asymmetry is documented in a series of early studies on TD sibling interactions in middle childhood (; ). ) found that the typical asymmetric role relationship was followed when children with ASD interacted with their infant younger siblings. On the other hand, , ) reported that typical asymmetric roles were not followed; younger or older TD siblings both initiated and imitated more than the ASD sibling. Using an adapted version of a coding system used by , , ), and ), we examined whether asymmetric roles are followed in sibling interaction in which the younger sibling has ASD. That is, do older TD siblings conduct more prosocial, discourse, play-related, and agonistic behaviors than their younger sibling, while younger ASD siblings imitate more? To that end, we analyzed both siblings’ behaviors during the interaction.

also reported that a high prevalence of positive or negative behaviors in one sibling was associated with a high prevalence of such behaviors in the other sibling. This pattern of association relates to point that the older TD sibling “enables participation in social interactions such as play and discourse”. In the present study, we inspected whether this pattern of association between prosocial behaviors is followed in TD/ASD sibling dyads. When the siblings are engaged in collaborative play (i.e., engaged with each other and playing together, in contrast to parallel play when each child plays alone), such an association can reflect coordination in the interactions, and not solely similarity in the siblings’ behaviors. Therefore, we started by examining whether the sibling dyadic interactions involved collaborative play.

In summary, based on the limited number of observational studies on ASD/TD siblings’ interaction, we examined prosocial behaviors in TD and ASD siblings during free-play at-home interactions. Although role asymmetry and association between siblings’ behaviors have been found in TD sibling dyads, potential social impairment inherent to an ASD diagnosis may elicit different results. First, we assessed whether the siblings’ dyadic interactions were collaborative. Second, we examined the typical asymmetric roles; that is, did the older TD sibling conduct more prosocial, discourse, play-related, and agonistic behaviors, and the younger ASD sibling imitate more? Third, we examined whether prosocial behaviors of the child with ASD are associated with those of the TD sibling, controlling for age, adaptive functioning level of the child with ASD, and other behaviors of the TD older sibling. Finally, we documented low-level behaviors, such as RRBI, and took these into account in the analysis.

Method

Participants

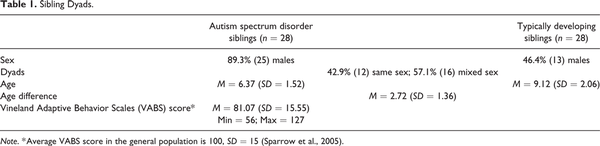

Twenty-eight Israeli Jewish sibling dyads participated. The inclusion criteria were a younger sibling with ASD (ASD-Sib) and an older sibling with no developmental or health problems, who are in a regular education classroom (TD-Sib). All ASD-Sibs were diagnosed at authorized medical centers/health care centers, where the Autism diagnostic observation schedule (ADOS, ; ADOS 2, ) is a part of the diagnostic battery. The ASD-Sibs demonstrated varied levels of functioning, as measured by the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS; ). The sample included two pairs of fraternal twins (boys), each of whom had one twin with ASD while the other was TD. Table 1 details the characteristics of the sibling dyads.

Fifty-seven percent of the families reported an income reflective of the average or above the average income for households in Israel, and the rest reported an income reflective of slightly under or under the average income.

Procedure

Data collection

Data collection was done via direct observations during home visits. The parents signed an informed consent form and completed a demographic questionnaire. The mothers completed a standard structured interview for assessing the adaptive functioning of the ASD-Sibs (VABS; ). At the beginning of the home visit, the researcher informed the children that she wished to see them playing as they usually play and clarified that they could stop the game and/or videotaping if they wanted. They were asked to choose a game and to play with it together for 10 min. Of the 10 filmed minutes, the middle 5 min were coded and analyzed (; ), using a coding system that was implemented into a program designed to analyze behavioral observations (INTERACT).

Coding

In a microanalytic frame-by-frame analysis, each action that occurred was counted and classified into one of the following behavioral categories: (1) prosocial (such as helping, praising, sharing, and comforting); (2) discourse (such as asking and sharing an experience or information not related directly to the ongoing play); (3) play-related (such as establishing roles and rules in the game ); (4) agonistic (such as a threat or an insult); (5) imitation (performing the same behavior as the other sibling); (6) low-level (i.e., incomplete or unclear behaviors such as speaking out of context, and RRBI, such as asking a repetitive question or hand-flapping upon winning a card in the game). The coding scheme was constructed by adapting and elaborating previously published interactional codes (; ; for low-level category, see ; ).

Additionally, each dyadic interaction was globally assessed as mostly collaborative (the siblings collaborate on the joint play for most of the interaction time) versus mostly parallel (the siblings spend most of the interaction time in parallel play).

Inter-rater reliability

Ten percent of the data were simultaneously coded by the researcher and another trained coder. The overall kappa for the counts and classification of actions was 0.80. Within specific categories, kappa values ranged from perfect to moderate () (prosocial: 0.63; discourse: 0.65; play: 0.81; agonistic: 0.58; imitation: 1.00; low-level: 0.58). When defining the interaction as collaborative versus parallel, there was a 100% agreement.

Data analysis

To examine whether a typical asymmetric role relationship between the siblings was followed, we compared behavior counts between the TD-Sibs and the ASD-Sibs. In light of the nature of the data (frequency counts), generalized linear models were used (). The distribution assumption was for a count variable, Poisson distribution, with an alteration to a negative binomial distribution (NBD) for overdispersion (; ). Then we examined associations between the frequency of the prosocial behaviors displayed by the ASD-Sib with those displayed by the TD-Sib. We further examined associations between the frequency of the prosocial behaviors displayed by the ASD-Sib with the other types of behaviors (see above), with the level of adaptive functioning and age of the ASD-Sib, and the age differences between siblings.

Results

First, to assess the nature of the siblings’ dyadic interactions, we collected descriptive measures regarding collaborative versus parallel play in the sibling interaction, and the behaviors of the older and younger siblings. Collaborative play characterized most pairs (78.6%). Prosocial behaviors were the second most frequently observed behaviors (pair average: 17.46, SD: 13.58), occurring after play-related behaviors (pair average: 45.07, SD: 28.24). Interestingly, the proportions of prosocial behaviors to all other categories of behaviors were similar for TD-Sibs and ASD-Sibs (20% and 16%, respectively; see supplementary materials for distributions of behaviors by categories for TD and ASD siblings).

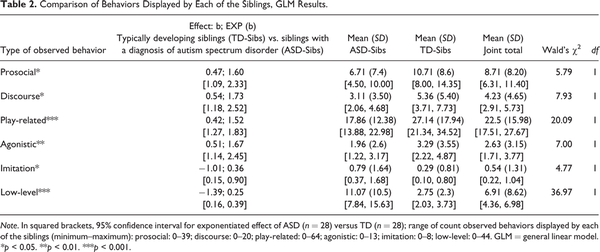

Second, to examine the typical asymmetric roles, we compared the number of actions between the older TD-Sibs and the ASD-Sibs by using a general linear model (GLM) where the action count distribution was assumed NBD (). The NBD distribution is a corrected Poisson distribution for overdispersion. Using the multilevel GLM with NBD assumption, we controlled for the TD-Sibs and the ASD-Sibs as dyads, and correlation within dyads was set as unstructured. Thus, in the GLM analysis, we clustered the TD-Sibs and the ASD-Sibs into pairs to control for within-pair behaviors. The Wald’s χ2 test for significance level was used. We provided the linear and the exponentiated effect, with the confidence interval around the exponentiated estimate, where the exponent value is the change in the count of the TD-Sibs versus ASD-Sibs’ behaviors. Consistent with typical asymmetric roles, TD-Sibs showed more prosocial, discourse, play-related, and agonistic behaviors, while ASD-Sibs showed more imitation and more low-level behaviors (Table 2). All differences remained significant when controlling for sex and the functioning level of the ASD-Sibs.

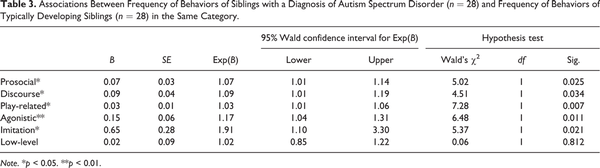

Third, using GLMs with NBD, we examined the association between the number of prosocial behaviors exhibited by TD-Sibs and ASD-Sibs. The same process was repeated for each of the other types of behaviors. Table 3 shows a summary of the associations between the TD-Sib’s measures on the ASD-Sib in separate models for each type of behavior.

As is seen in Table 3, the number of prosocial behaviors displayed by the ASD-Sibs was significantly associated with the number of prosocial behaviors displayed by the TD-Sibs. The same pattern was found regarding discourse, play-related, agonistic, and imitative behaviors. Meaning, the number of behaviors displayed by the TD-Sib was significantly associated with the number of behaviors of the same kind displayed by the ASD-Sib. Only the low-level behaviors of the ASD-Sibs, which are characteristic to individuals with this diagnosis, were not associated with the number of low-level behaviors exhibited by the TD-Sibs, nor with any of the other examined variables.

Next, the effect of age and adaptive functioning level of the ASD-Sib, age difference between siblings, and the other behaviors of the TD-sib (discourse, play-related, agonistic, imitation, and low-level) were added to the model predicting prosocial behaviors of the ASD-Sib. None of the additional controls contributed any additional significance; the number of prosocial behaviors displayed by the TD-Sibs was the only variable that was significantly associated with the number of prosocial behaviors displayed by the ASD-Sibs. Adding many variables into the model may increase the likelihood of a type I error. However, the fact that the same pattern was found across categories of behaviors, excluding low-level behaviors, reinforces the validity of these findings.

Discussion

This study reports on the prosocial behaviors of children with ASD during the interaction with their older TD siblings, using an observational, naturalistic design with a frame-by-frame analytic computerized tool. Analyses indicated that prosocial behaviors were frequently observed in at-home free-play sibling interaction between TD and ASD siblings. We found a generally collaborative play and a positive nature of sibling dyadic interactions: play-related and prosocial behaviors were the most frequent behaviors in the interaction.

Asymmetric roles were identified during the interaction; older siblings conducted more prosocial, discourse, play-related, and agonistic, behaviors, while the younger sibling imitated more. Moreover, significant associations were found between prosocial behaviors of the two siblings in each dyad; this pattern was held across all categories of behavior, except for low-level behaviors. These findings are consistent with role asymmetry and associations between siblings’ behaviors in TD dyads (e.g., ). However, considering the social challenges inherent in ASD, the findings from this study suggest that sibling interaction is a valuable social context for developing and practicing prosocial behaviors in children with ASD.

Low-level behaviors were significantly more frequent among the children with ASD and did not follow the pattern of association with TD siblings’ behavior. Moreover, age and functioning level adaptive function of the ASD sibling, nor any of the measured behaviors of the TD sibling, were associated with the low-level behaviors of the ASD sibling. In other words, these behaviors may be seen as being “left out” of the dyadic coordination. Low-level behaviors were specified as unclear, incomplete social actions or as RRBI, which constitute a defining characteristic of ASD (). The lack of association with TD siblings’ behavior could indicate that low-level behaviors were accepted with no special attention, or even ignored, because the TD siblings are used to these behaviors. Thus, the children’s low-level behaviors did not interfere with the flow of dyadic interaction and or coordination between siblings. This aspect of sibling relations may be related to the generally positive and collaborative play observed in the interaction.

Altogether, the findings of an asymmetric role relationship and coordination in the sibling dyadic interaction suggest that modeling by an older TD sibling and a generally collaborative and accepting social environment are possible explanations for findings of an association between better social outcomes in children with ASD and the presence of older TD siblings in the family. Our findings indicate that children with ASD benefit from coordinated interactions with older siblings.

Study Limitation and Future Research

Microanalysis is time-consuming in comparison to other methods, such as global or intuitive coding (; ). At the same time, it allows for an in-depth, rich, detailed investigation, including, for example, characterization of several behaviors that occur at the same time and influence each other. The utilization of a frame-by-frame analysis of video-recorded data is highly beneficial for capturing behaviors that would have likely been missed using other methods. Since microanalysis produces large data, it is often utilized with relatively small samples (). The current data set consisted of 28 dyads. Previous observational studies that examined sibling interactions in the context of ASD had similar or fewer TD/ASD sibling dyads (; ; ). However, future studies should aim for larger samples and, specifically, should increase the number of participating females with ASD. Although the male:female ratio in the current study was similar to the reported ratio in Israel (), the small number of females in our sample made it impossible to draw conclusions on possible gender differences. Another limitation is that the TD siblings were included based on parental reports. Future studies should assess TD siblings for cognitive functioning, temperament, and personality traits since such variables might influence sibling interaction. In future studies, we suggest addressing the inter-rater agreement of the coding of agonistic and low-level behaviors, which reached lower kappa values (0.58) than other behaviors in our study. Kappa is a more stringent measure that corrects for the likelihood of chance agreement. Finally, children were asked to play a favored game, which may prompt higher levels of positive behaviors. The findings need to be considered within the context of playing a familiar, preferred game in a natural environment. Future studies could examine prosocial behaviors in different contexts (i.e., home and laboratory) and use experimental manipulations (e.g., instructing the TD sibling to behave in a certain way) to explore causal relationships in sibling interactions.

Significance and Implications

Contemporary perspectives challenge the assumption that individuals with ASD lack social interest and point to the need to investigate various ways in which they may express their social motivation (). Our results add to that perspective, emphasizing the role of the social partner and the interaction setting as important variables in characterizing social behaviors in children with ASD. Even though a sibling is a potentially close, available social partner, and the home environment is central in the life of a child with ASD, little research is available in this area. Our findings highlight the importance of sibling interactions at home and support the hypothesis that sibling interactions provide an opportunity for children with ASD to practice prosocial behaviors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the families who participated in this study. YR is grateful to the Azrieli Foundation for the award of an Azrieli Fellowship and support for research expenses. Participants received a game worth 100 NIS (equivalent to USD$20–25) in gratitude for their participation.

Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Yonat Rum

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8883-8606

Supplemental material Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Notes

1. This study is a part of a larger research (). The participating children with ASD were also observed interacting with their mothers and friends, and during other tasks, over several home visits.

2. In the case of helping the sibling during play, the behavior was coded as “help,” that is, as prosocial. Play-related behaviors demonstrated a playful, positive nature, but not a clear observed intention of conducting a prosocial action.

References

- Abramovitch R., Corter C., Pepler D. J., Stanhope L. (1986). Sibling and peer interaction: A final follow-up and a comparison. Child Development, 57(1), 217–229.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Author.

- Bauminger-Zviely N. (2013). Social and academic abilities in children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Guilford Press.

- Ben-Itzchak E., Nachshon N., Zachor D. A. (2018). Having siblings is associated with better social functioning in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47(5), 1–11.

- Ben-Itzchak E., Zukerman G., Zachor D. A. (2016). Having older siblings is associated with less severe social communication symptoms in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(8), 1613–1620.

- Bontinck C., Warreyn P., Meirsschaut M., Roeyers H. (2018a). Parent–child interaction in children with autism spectrum disorder and their siblings: Choosing a coding strategy. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(1), 91–102.

- Bontinck C., Warreyn P., Van der Paelt S., Demurie E., Roeyers H. (2018b). The early development of infant siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder: Characteristics of sibling interactions. PLoS One, 13(3), e0193367.

- Brody G. H. (2004). Siblings’ direct and indirect contributions to child development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(3), 124–126.

- Cohen P., West S. G., Aiken L. S. (2014). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Psychology Press.

- Coxe S., West S. G., Aiken L. S. (2009). The analysis of count data: A gentle introduction to Poisson regression and its alternatives. Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 121–136.

- Deschamps P. K., Been M., Matthys W. (2014). Empathy and empathy induced prosocial behavior in 6- and 7-year-olds with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(7), 1749–1758.

- Dunn J. (1992). Sibling and development. Current Direction in Psychological Science, 1(1), 6–9.

- El-Ghoroury N. H., Romanczyk R. G. (1999). Play interactions of family members towards children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 29(3), 249–258.

- Haidet K. K., Tate J., Divirgilio-Thomas D., Kolanowski A., Happ M. B. (2009). Methods to improve reliability of video-recorded behavioral data. Research in Nursing & Health, 32(4), 465–474.

- Hauck M., Fein D., Waterhouse L., Feinstein C. (1995). Social initiations by autistic children to adults and other children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 25(6), 579–595.

- Hilbe J. M. (2017). The statistical analysis of count data/El análisis estadístico de los datos de recuento. Cultura y Educación, 29(3), 409–460.

- Jameel L., Vyas K., Bellesi G., Roberts V., Channon S. (2014). Going “above and beyond”: Are those high in autistic traits less prosocial? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(8), 1846–1858.

- Jaswal V. K., Akhtar N. (2019). Being versus appearing socially uninterested: Challenging assumptions about social motivation in autism. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 42, 1–73.

- Knott F., Lewis C., Williams T. (1995). Sibling interaction of children with learning disabilities: A comparison of autism and Down’s syndrome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 36(6), 965–976.

- Knott F., Lewis C., Williams T. (2007). Sibling interaction of children with autism: Development over 12 months. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(10), 1987–1995.

- Landis J. R., Koch G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174.

- Lord C., Rutter M., DiLavore P. C., Risi S. (1999). Autism diagnostic observation schedule-WPS Edition. Western Psychological Services.

- Lord C., Rutter M., DiLavore P. C., Risi S., Gotham K., Bishop S. (2012). Autism diagnostic observation schedule (2nd ed.). Western Psychological Services.

- McDonald N. M., Messinger D. S. (2012). Empathic responding in toddlers at risk for an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(8), 1566–1573.

- Meirsschaut M., Warreyn P., Roeyers H. (2011). What is the impact of autism on mother–child interactions within families with a child with autism spectrum disorder? Autism Research, 4(5), 358–367.

- Pepler D. J., Abramovitch R., Corter C. (1981). Sibling interaction in the home: A longitudinal study. Child Development, 52(4), 1344–1347.

- Prime H., Perlman M., Tackett J. L., Jenkins J. M. (2014). Cognitive sensitivity in sibling interactions: Development of the construct and comparison of two coding methodologies. Early Education and Development, 25(2), 240–258.

- Raz R., Weisskopf M. G., Davidovitch M., Pinto O., Levine H. (2015). Differences in autism spectrum disorders incidence by sub-populations in Israel 1992–2009: A total population study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(4), 1062–1069.

- Rum Y. (2020). Children with ASD and their siblings—an interaction study [Doctoral dissertation, Tel Aviv University) (Hebrew).

- Russell G., Golding J., Norwich B., Emond A., Ford T., Steer C. (2012). Social and behavioural outcomes in children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders: A longitudinal cohort study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(7), 735–744.

- Sparrow S. S., Cicchetti D. V., Balla D. A., Doll E. A. (2005). Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales: Survey forms manual. American Guidance Service.

- Totsika V., Hastings R. P., Emerson E., Berridge D. M., Lancaster G. A. (2015). Prosocial skills in young children with autism, and their mothers’ psychological well-being: Longitudinal relationships. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 13, 25–31.