The youth population of a country is considered its demographic dividend due to the economic payoffs of the working-age population entering the workforce. The potential of this valuable resource can be realized only if it is nurtured, protected, and allowed to develop to its fullest potential by providing good health, quality education, and decent employment. Youth development is influenced by their immediate surroundings (microenvironment) and more prominent societal factors (macroenvironment). The macroenvironment, among other things, includes the legal frameworks and policies of a country, which directly influences young people’s health and well-being.

Mental health is an essential component of well-being. Evidence suggests that childhood mental health problems are associated with more significant risks of school absenteeism, suicide, and self-harm in the short term., Further evidence suggests that in the long term, childhood psychological issues are associated with lower educational attainment, employment prospects, social mobility, marriage stability, and other psychological characteristics that enable social engagement compared to physical health problems.

How mental health has been viewed in children has undergone a cultural change, which has also been reflected in government policies. A review summarized how a child’s needs have been viewed over the years. Specifically on mental health, the authors mention that there was initially a developmental nihilism with society not taking an active interest in setting goals for children as their development was considered to be due to immutable biological or social factors. Children’s mental health needs in the past have been considered an optional or discretionary good. There are concerns of over medicalization of the mental health of children now. Most countries now consider a child’s mental health and well-being as a right.

The history of the development of child rights internationally is relatively recent. In the aftermath of World War I, children were finally recognized as individuals in their own right rather than extensions of adults. This led to the League of Nations ratifying the Geneva Declaration in 1924, which, in its preamble, mentions, “Mankind owes to the child the best that it has to give.” Though not a bill of rights but more a list of adults’ obligations toward children, the declaration was the first international document that addressed children in their own rights. Following this, several international treaties and conventions addressed various aspects of child rights, including protection from exploitation and a right to education. In 1989, the UN General Assembly adopted the International Convention on the Rights of the Child(UNCRC), which set the minimum standards for protecting children’s rights. The UNCRC has become the most widely ratified international document, with 196 countries ratifying it.

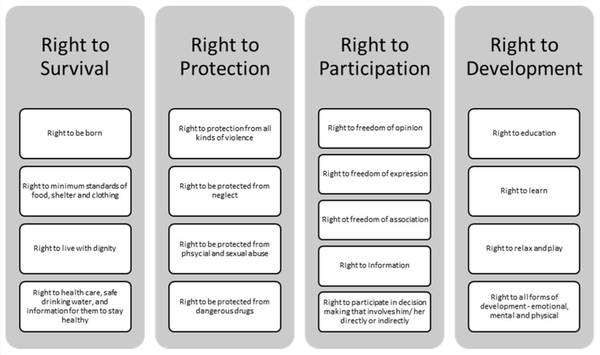

The UNCRC has 54 articles broadly classified under the four headings of principles, provisions, protection, and participation. The guiding principles of the UNCRC include the child’s best interests, respect for the child’s views, nondiscrimination, and survival and development. These rights are classified under the headings of right to survival, protection, participation, and development. The various rights are shown in Figure 1. While the right to health has been considered fundamental, children are especially vulnerable as they depend on adults to make decisions on their behalf.

Rights of the Children as Mentioned in the UNCRC.

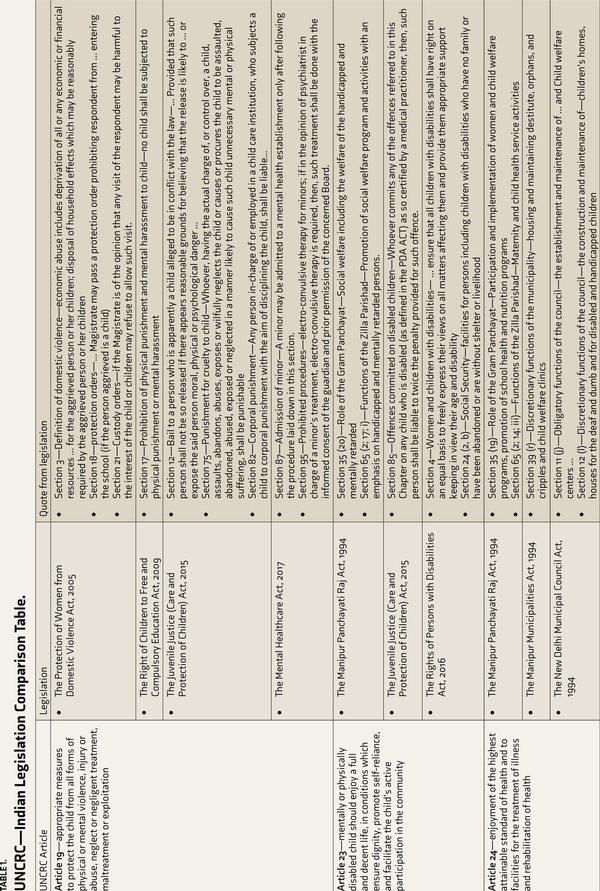

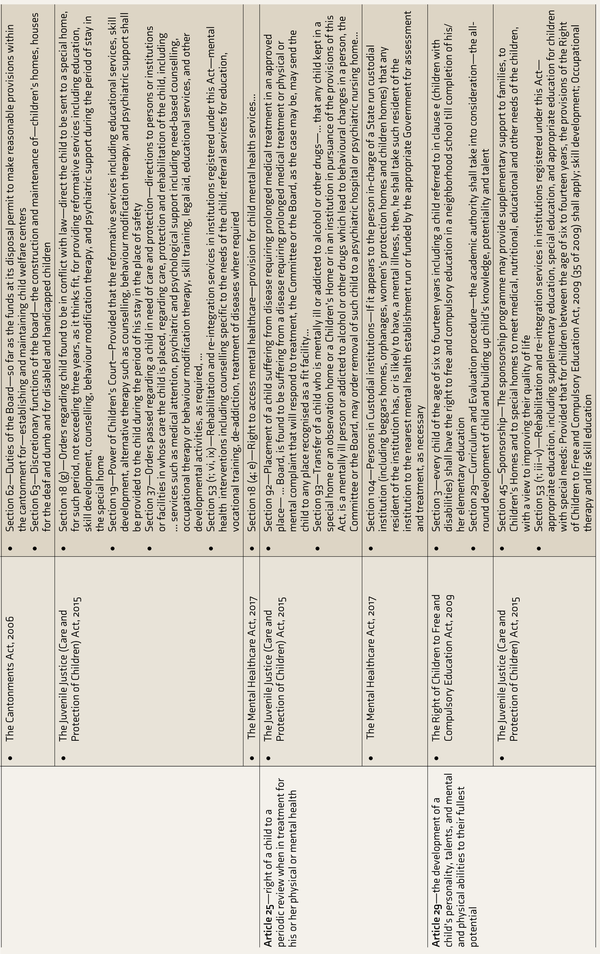

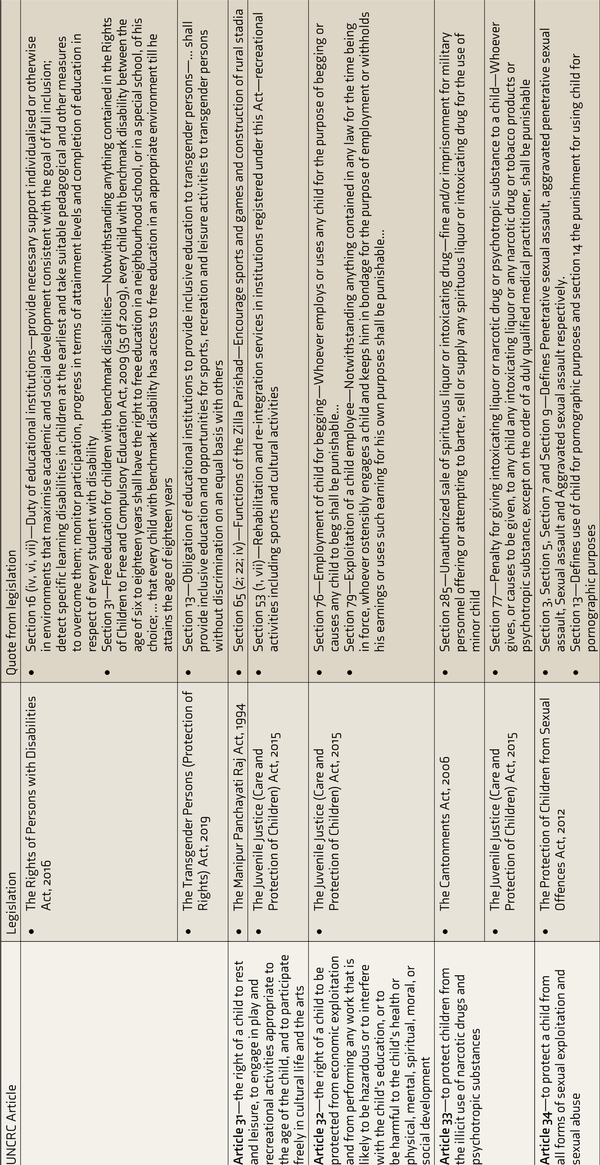

Although all four headings mentioned above are relevant to the mental health, well-being, and development of children, some articles of the UNCRC specifically address these aspects. Article 19 mentions “appropriate measures to protect the child from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation.” Article 23 states: “a mentally or physically disabled child should enjoy a full and decent life…preventive health care and of medical, psychological and functional treatment of disabled children.” Furthermore, Article 24 deals with “the highest attainable standard of health and to the facilities for the treatment of illness and rehabilitation of health.”

Article 25 addresses the right of the “child who has been placed by the competent authorities for the purposes of care, protection or treatment of his or her physical or mental health, to a periodic review of the treatment provided to the child and all other circumstances relevant to his or her placement.” Holistically, Article 31 recognizes the right to rest and leisure. In contrast, Article 32 prevents exploitation that might harm a child’s mental and social development, and Article 33 aims to protect children from the use of illicit drugs.

Translating the UNCRC into practical steps requires governments to use it as a guide to policymaking. India ratified the UNCRC on December 11, 1992. Over the years, in India, children have been acknowledged and afforded fundamental rights (see Box 1), and several laws have been created or amended to address the needs of children to protect their interests directly. We aimed to review the overlap of the UNCRC and the legislative policies in India directed toward children. Our focus would be restricted to legislations implemented at the central governmental level and will mention aspects of child mental health.

Constitutional Rights Afforded to Children in the Indian Constitution.

Rights of Children in the Indian Constitution

• Article 21A—Right to education for children between 6 and 14 years: “The State shall provide free and compulsory education to all children of the age of six to fourteen years in such manner as the State may, by law, determine.”• Article 24—Children below the age of 14 years shall not work in any hazardous employment: “No child below the age of fourteen years shall be employed to work in any factory or mine or engaged in any other hazardous employment.”• Article 39(e)—Children should not be abused: “… and the tender age of children are not abused and that citizens are not forced by economic necessity to enter avocations unsuited to their age or strength.”• Article 39(f)—Children are to be afforded opportunities and facilities to develop: “that children are given opportunities and facilities to develop in a healthy manner and in conditions of freedom and dignity and that childhood and youth are protected against exploitation and against moral and material abandonment.”• Article 45—State should provide early childhood education: “The State shall endeavour to provide … for free and compulsory education for all children until they complete the age of fourteen years.”

Method

First, both the authors familiarized themselves with all the articles of the UNCRC. Following this, a keyword search for “Child” with limits of Central Acts was conducted in the national portal for Indian legislation—www.indiacode.nic.in—in May 2023. The results were restricted to Acts that were active and enacted after December 1992 (when India ratified the UNCRC). Following this, both authors extracted the full text of the legislation and independently reviewed it for information related to children’s mental health or UNCRC.

Consensus between the authors determined any disagreement in the selection of legislation. Once the legislation was selected, the information from the legislation was mapped onto the various articles of the UNCRC. For this review, we restricted the mapping exercise to a few Articles (Articles 19, 23, 24, 25, 29, 31, 32, 33, and 34) of the UNCRC that directly address children’s mental health and well-being. A comparative analysis assessed how India’s legislation protects and addresses children’s rights, especially regarding their mental health.

Results

A search with the keyword resulted in 98 Central Acts on the website. Of these, 32 were enacted after December 1992. Of these, 11 (shown in Table 1) were selected based on whether mental or emotional health was mentioned in the legislation or addressed factors directly related to children’s mental health. Only three pieces of legislation—the Commissions for Protection of Child Rights Act, 2005 (not included in the review), the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act 2012], and the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) (JJ) Act 2015—cited the UNCRC in their preamble.

The definition of child varied across the different Central Acts. The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act 2005, the POCSO Act 2012, the JJ Act 2015, and the Mental Healthcare Act (MHCA), 2017 define a child as any person below the age of 18 years. The Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006 identifies a child as a male who has not completed 21 years of age and a female who has not completed 18 years of age. The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education (RTE) Act, 2009 addresses children as individuals between the ages of 6 and 14 years.

Four legislations directly address protecting children from all kinds of violence, negligence, or exploitation (Article 19). The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act 2005 includes abuse or neglect directed toward a child (including adopted, foster, or stepchild) in the family and the aggrieved person. This Act also provides a legal recourse to protect the child from harm by restricting access through protection or custody orders. The RTE Act and the JJ Act categorically prohibit the use of physical disciplining and mental harassment in the academic setting and within childcare institutions. The JJ Act also prescribes that the JJ Board can deny a child bail if there is concern that the child would be exposed to moral, physical, or psychological danger and determines the punishment to be dealt to an individual for cruelty to a child. The MHCA sets a higher standard to ensure the safety of minors in mental health institutions and for specific treatments such as modified electro-convulsive therapy.

Article 23 protects the interests and rights of mentally and physically disabled children. The Manipur Panchayati Raj Act 1994 emphasizes the role of the local governance (Gram and Zilla Panchayats) to ensure that social welfare programs are created and implemented for “handicapped and mentally retarded persons.” The Rights of Persons with Disabilities (PWD) Act 2016 takes a rights-based and participatory approach to support women and children with various disabilities. The JJ Act 2015 prescribes that if children with disabilities are harmed, the accused should bear twice the penalty for the offense committed.

Article 24 of the UNCRC gives the right to the highest attainable standard of health for children, and access to mental health care for children is enshrined in the MHCA. The Manipur Panchayati Raj Act 1994, the Manipur Municipalities Act 1994, the New Delhi Municipal Council Act 1994, and the Cantonments Act 2006 emphasize the need for the local governments to create and maintain child welfare clinics. One of the discretionary requirements is the construction and maintenance of children’s homes for the vulnerable and disabled. The JJ Act identifies mental health care with behavior modification, counseling, and psychiatric support as integral to reforming children in conflict with the law. Article 25 is addressed in the JJ Act and the MHCA with respect to the treatment of mental health conditions of children in custodial settings. The care of children who need inpatient mental health services from childcare institutions is addressed in the JJ Act and the MHCA.

The development of a child’s abilities and talents (Article 29) is the focus of the RTE Act, focusing on providing an opportunity (free and compulsory education) and encouraging an all-round evaluation and development of the child. The JJ Act sponsors families and institutions that cannot provide for the children’s development and makes it an essential part of the rehabilitation and reintegration services. The PWD Act makes it the duty of the educational institutions to identify such children, provide them appropriate support, and monitor participation and progress of every student with disabilities with a focus on inclusion. This is also reflected in the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act 2019, which focuses on inclusive educational institutions for gender-diverse individuals.

Article 31 is addressed in the Manipur Panchayati Raj Act 1994, where the responsibility of creating opportunities to participate in sports and games lies with the Zilla Parishad. As part of the rehabilitation and reintegration of children, the JJ Act recommends the provision of sports and cultural activities. The Cantonments Act 2006 and the JJ Act prescribe penalties for individuals who attempt to provide any alcohol or intoxicating substance to children, thereby supporting Article 33 of the UNCRC.

Of all the Articles of the UNCRC, Article 32 (right to be protected from exploitation) and Article 34 (protection of children from all forms of sexual exploitation and abuse) are represented in only one legislation each. In the description of the Children in Need of Care and Protection, the JJ Act protects a child from either begging or exploitation and identifies it as a punishable offense. Similarly, various sections of the POCSO Act define the different kinds of sexual assaults and the associated punishments. Additionally, a separate section addresses the punishment for using children for pornographic purposes. It is essential to recognize that the POCSO Act defines aggravated penetrative and aggravated sexual assaults as something “that causes the child to become mentally ill.”

Discussion

This comparative review highlights the interplay between the international standards (as established by the UNCRC) and the legislation in India, specifically focusing on child mental health. One key finding is that nearly a third (11 of 32) of the laws enacted from 1992 that address some aspect of children have any direct or indirect reference to their mental health. One pattern that does emerge is that even though the initial few laws were focused on protecting the well-being of children, the latter laws (e.g., the JJ Act, MHCA) specifically take a rights-based approach to children’s mental health, as has been discussed in a discussion paper by UNICEF. This is also witnessed in the choice of words that were used to describe children with disabilities, such as “handicapped and mentally retarded” being used in earlier laws and persons with disabilities in the latter ones.

Mental health is a fundamental right, as stated in the preamble of the World Health Organization. Health is defined as a positive concept—“the complete state of physical, emotional and social wellbeing”. Even though Article 31 of the UNCRC discusses the need for rest and leisure, only two Acts categorically provide a legal mandate to implement this. Mental health as a positive concept has also been acknowledged in the Sustainable Developmental Goals (SDG) 3 of Good Health and Wellbeing. This is further clarified under the target SDG 3.4—“to reduce by one-third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment and promote mental health and well-being”—and SDG 3.5—“strengthen the prevention and treatment of substance abuse, including narcotic drug abuse and harmful use of alcohol”. The impact on children’s mental health problems cannot be overstated, as evidenced by the large-scale population-based study in Britain, which showed that mental health problems in childhood affect their economic abilities, marriage stability, and overall social mobility.

Our review using systematic search terms and a focus on mental health revealed that only 11 of the Acts implemented at the center have aligned themselves with the UNCRC. In comparison, when Article 24 alone was considered broadly in a review, only four countries in the Eurozone were noted to have enshrined in their legislation a specific legal disposition for universal health care for all children, irrespective of their legal status. Several barriers have been identified to providing appropriate health care for children in India of all ages. These include structural issues such as poverty, economic inequality, illiteracy, misinformation, inadequate allocation of resources, and programmatic issues such as the implementation of programs.

The principles of the UNCRC include the right to participation, protection, development, and survival. While the right to participation is a part of the UNCRC, only the JJ Act mentions participation, even when not under the heading of mental health care. The MHCA and the JJ Act take on a more paternalistic role in the involvement of children in their care, for example, having the parents/guardians of minors make decisions about the child’s treatment. There is a description of child welfare activities and fostering sports, games, and cultural activities in the laws that focus on children’s holistic development. One of the review’s key findings was that a special emphasis was placed on promoting health and development among children with disabilities.

Considering the perspective of addressing the social determinants of mental health, the laws reviewed here show a significant initiative of the government to keep children safe from some psychosocial stressors. In almost every scenario where children are present—either in the presence of caregivers and academic institutions or under the government’s care—the laws protect them from physical, sexual, or emotional harm. The protection of children from drugs and intoxicants is also mentioned in the laws.

This article highlights where the law has not updated the current knowledge. For example, the POCSO Act mentions the effects of aggravated sexual assault on the victim’s mental health without acknowledging the effects of other forms of victimization. For example, bullying (including eve teasing), stalking (including cyber-stalking), verbal violence, and discrimination toward females and gender-diverse individuals also have a significant association with children developing mental health issues. These non-contact forms of sexual harassment are implied to be subsumed under the mental health effects of sexual harassment.

As seen in the “Results” section, there is a wide variation in the definition of children’s age that the specific laws address. While this might be appropriate for some laws, such as the RTE, that address early childhood education, it may criminalize typical adolescent phenomena such as consensual sexual exploration. This may lead to confusion in implementing a specific policy that provides protection and services to children. The laws are also silent regarding consent for medical procedures and engagement in research commensurate with the child’s developmental abilities. This is important as both clinical and research work with children about conditions that specifically affect children or have their onset in childhood are addressed differently than those emerging later in life.

One of the major limitations of this study is that no rules of implementation, policies, or state laws were reviewed. These could have given more information about how the UNCRC has been implemented in India. Furthermore, how the UNCRC is interpreted in case law gives the current trends in its implementation. This was also not explored as a part of this review. This work’s future directions should include these legal and policy framework components to understand the actual implementation of UNCRC. This would also help understand the impact of the legislation on the overall mental health and well-being of children. Some legislation is harmonized with the United Nations Commission on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD). This review did not pursue the UNCRC and the UNCRPD intersection, which could have highlighted the overlap between these related standards. This review also highlights the need for clinicians to be aware of the changing trends in how the law interprets child rights in the context of mental health and in advocating for children’s rights under the UNCRC framework.

This article paves the path for furthering knowledge by assessing the impact of legislation on children’s mental health outcomes. Furthermore, improving age definitions ensures avoiding confusion and consistency in protecting their rights. The authors would caution that while the UNCRC provides useful guidance for enacting child-focused legislation, it must always be considered in the context of the prevailing local conditions. This is especially true in a country like India, with a strong and extended family structure to support children. This is an evolving and modifiable phenomenon, as evidenced by India’s legislative history. Thus, policy advocacy with a participatory model comprising all stakeholders, including youth, families, community leaders, and mental health professionals, would be the logical way to influence the development of appropriate child-focused mental health policies. Creating specific guidance for mental health professionals on evaluating and engaging young people in decision-making will ensure the appropriate implementation of the UNCRC at all levels of care.

Conclusion

“Mankind owes to the child the best that it has to give” cannot be stated without ensuring that children have access to the highest level of mental health—focusing on their growth and development and addressing their mental health concerns. India has made significant progress in implementing the UNCRC at the legislative level. Still, the impact is not yet felt by the persons implementing/delivering mental health–related interventions such as health prevention, promotion, and treatment of mental health conditions. At the clinical level, care remains paternalistic. Implementing the value of respecting a child’s view would include active participation in their care through discussions and delivering positive mental health interventions in a participatory model with youth from different communities.

Furthermore, this article also highlights the need for all stakeholders including health professionals and policy makers to work collaboratively to create and implement policies that aid children’s mental health. This will enable us to realize the greater goal of the UNCRC, which envisions a world where children are valued, protected, and empowered to participate in society as active and responsible citizens.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. UNFPA. Demographic dividend, https://www.unfpa.org/demographic-dividend#readmore-expand ( , 2022).

- 2. Keith P, Hawton K, Saunders KEA, . Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet, 2012; 379: 2373–2382. http://www.thelancet.com.

- 3. Lawrence D, Dawson V, Houghton S, . Impact of mental disorders on attendance at school. Aust J Educ, 2019, ;63(1): 5–21. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0004944118823576.

- 4. Goodman A, Joyce R, Smith JP. The long shadow cast by childhood physical and mental problems on adult life. Proc Natl Acad Sci, 2011, ;108(15): 6032–6037. https://pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1016970108.

- 5. Harper G, Çetin FÇ. Child and adolescent mental health policy: Promise to provision. Int Rev Psychiatry, 2008, ;20(3): 217–224. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09540260802030559.

- 6. Humanium. Standard references on child rights, https://www.humanium.org/en/references-on-child-rights ( , 2023).

- 7. United Nations General Assembly. Convention on the Rights of the Child by General Assembly resolution 44/25, https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx (1989).

- 8. Government of India. The Commissions for Protection of Child Rights Act, 2005. Gazette of India, 4 of 2006, http://www.indiacode.nic.in ( , 2006).

- 9. Government of India. The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012. Gazette of India, 32 of 2012, http://www.indiacode.nic.in ( , 2012).

- 10. Government of India. Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act 2015. Gazette of India, 2 of 2016, http://www.indiacode.nic.in ( , 2016), https://wcd.nic.in/sites/default/files/JJAct,2015_0.pdf.

- 11. Government of India. The Protection Of Women From Domestic Violence Act, 2005. Gazette of India, 43 of 2005, http://www.indiacode.nic.in ( , 2005).

- 12. Government of India. The Mental Healthcare Act, 2017. Gazette of India, 10 of 2017, http://www.indiacode.nic.in ( , 2017).

- 13. Government of India. The Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006. Gazette of India, 6 of 2007, http://www.indiacode.nic.in ( , 2007).

- 14. Government of India. The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009. Gazette of India, 35 of 2009, http://www.indiacode.nic.in ( , 2009).

- 15. Government of India. The Manipur Panchayati Raj Act, 1994. Gazette of India, 26 of 1994, http://www.indiacode.nic.in ( , 1994).

- 16. Government of India. The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016. Gazette of India, 49 of 2016, http://www.indiacode.nic.in ( , 2016).

- 17. Government of India. The Manipur Municipalities Act, 1994. Gazette of India, 43 of 1994, http://www.indiacode.nic.in ( , 1994).

- 18. Government of India. The New Delhi Municipal Council Act, 1994. Gazette of India, 44 of 1994, http://www.indiacode.nic.in ( , 1994).

- 19. Government of India. The Cantonments Act, 2006. Gazette of India, 41 of 2006, http://www.indiacode.nic.in ( , 2006).

- 20. Government of India. The Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019. Gazette of India, 40 of 2019, http://www.indiacode.nic.in ( , 2019).

- 21. UNICEF. Discussion Paper: A Rights-based Approach to Disability in the Context of Mental Health. New York; 2021 , https://www.unicef.org/media/95836/file/A%20Rights-Based%20Approach%20to%20Disability%20in%20the%20Context%20of%20Mental%20Health.pdf.

- 22. Grad FP. The preamble of the constitution of the World Health Organization. Bull World Health Organ, 2002; 80(12): 981–984. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/268691/PMC2567708.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- 23. United Nations. Take action for the Sustainable Development Goals—United Nations Sustainable Development, https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/.

- 24. Palm W. Children’s Universal Right to Health Care in the EU: Compliance with the UNCRC. Eurohealth, 2017; 23(4): 3–6.

- 25. Srivastava R. Right to health for children. Indian Pediatr, 2015; 52: 15–18. https://www.indianpediatrics.net/jan2015/jan-15-18.htm.

- 26. Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, . Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet, 2012, ; 379(9826): 1641–1652. http://www.thelancet.com/article/S0140673612601494/fulltext.

- 27. Sheffler JL, Stanley I, Sachs-Ericsson N. ACEs and mental health outcomes. In: Adverse childhood experiences. Elsevier, 2020, pp. 47–69. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780128160657000045.

- 28. Anchan V, Janardhana N, Kommu JVS. POCSO Act, 2012: Consensual sex as a matter of tug of war between developmental need and legal obligation for the adolescents in India. Indian J Psychol Med, 2021, ; 43(2): 158–162. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0253717620957507.