Dissociative disorder is characterized by a feeling of being outside one’s body or a loss of memory, identity, emotion, behavior, or a sense of self. It is usually considered as a complex and chronic disorder and usually occurs after a traumatic event. Dissociative identity disorder (DID) is a subtype of dissociative disorder which is most complex and chronic in nature as well as constitutes an overarching syndrome covering all dissociative phenomena. Attachment theory of dissociation states that traumatic childhood experiencing in the form of rejection or emotional neglect by the caregiver can lead to disorganized attachment style, making it difficult to develop trustful adult relationships and increasing the likelihood of developing dissociative symptoms later in life. Kluft’s four-factor theory emphasizes that family chaos, inconsistency in parenting in terms of parental demand and reinforcement style, modeling of dissociation, and inadequate emotional support from parents can act as risk factors for developing dissociation.

Taking these factors into consideration, the current study tries to examine the relationship between a client’s dissociation and parental inconsistency and how the client was using dissociation to maintain homeostasis and reduce conflict within the family. Psychotherapy with the client needed to be eclectic in approach, focusing on providing support, reducing symptoms, enhancing coping skills, and integrating traumatic memories. Family therapy in such cases should identify dysfunctional structure, close and rigid boundaries, power differentials within the relationship, and how it affects interaction pattern and developmental issues that maintain problems within the family.

Case Introduction

The client was a 21-year-old single Hindu male from middle socioeconomic status. He was from an urban area of Trivandrum, Kerala, and had studied up to secondary. He was admitted to a tertiary hospital located in south India, which provides treatment and therapeutic services to people all over India. The client was referred by the psychiatrist concerned as a regular case referral for family therapy. An in-depth analysis of the case was done by using the case study method.

The stages of treatment were building therapeutic alliance, assessment, case conceptualization, goal setting, interventions, and termination.

Stage 1: Building a Therapeutic Alliance

The initial stage of treatment focused on building rapport and creating trust in the therapeutic process. The therapist explained to the client and the family that symptoms are a by-product of dysfunctions within the family and reassured them that they will not be asked to tackle any issues within the family that they are not comfortable in addressing. The therapist maintained professional objectivity while maintaining a strong therapeutic alliance and empowering the client’s and family’s abilities for self-regulation and willingness to bring change within the family structure.

Stage 2: Assessment

Chief Complaints

The client presented with 3 months’ illness characterized by his mind and body being taken over by another person named “Robot.” The other self of the client, as “Robot,” appeared whenever the client’s father criticized him or expressed his disappointment on seeing the client not being able to stand up to the father’s expectations. There were also anger outbursts, directed mostly towards the parents; they were secondary to the interpersonal issues with the father. For 3 months, the client also had difficulty in concentration, muttering to self, feeling sad and helpless, decreased need for sleep, and poor self-care, secondary to dissociation.

Treatment History

This was the first admission for the client, and he had not received any treatment or therapy before. When admitted to the hospital, he was given on a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) to reduce emotional distress. Once the behavioral manifestations of the symptoms reduced and the client stabilized, he and parents were referred for family therapy.

Clinical Diagnosis

As per ICD-10, a diagnosis of DID was made.

Assessment

The client’s background information and the presenting concern were assessed by following the Meyer and Gross’ psychiatric assessment proforma. The proforma gives guidelines for assessing the history of psychiatric symptoms; premorbid personality; personal history in terms of education, employment, and functionality; and past treatment history. The family assessment was done by following structural family therapy’s (SFT) four-step model. This model states that assessment is not just about information gathering but a more active and dynamic process that requires four steps: (a) exploring presenting problems from the family’s perspective; (b) highlighting dysfunctional structures, boundaries; and subsystems; (c) understanding why the family is maintaining homeostasis and the current interaction pattern; and (d) developing a shared understanding of the problem and designing a roadmap to the change.

Stage 3: Case Conceptualization

This case study can be conceptualized through an integrated theoretical framework by making use of both attachment theory model and SFT model., One of the developmental needs of the child when growing older is to individuate, develop, and grow as a person. At this stage, parental criticism or rejection and high control increase the conflict within the family. SFT can be one of the most appropriate models of family therapy in such cases as it focuses on improving parental practices and makes the family more cohesive by restructuring the boundaries and subsystem.,

Individual Level

Dissociation arose in this client due to a disorganized attachment style with the father, which was a result of rejection by the father. The rejection led to a difficulty to form a cohesive, unified personality and negatively affected the client’s selfesteem, problem-solving skills, stress tolerance, and coping skills.

The client had completed higher secondary education and was planning to pursue graduation. He was good in studies and never had any stress related to the studies.

After the onset of the illness, the client became socially withdrawn and developed poor self-care; the parents had to give repeated prompts for taking a bath or changing clothes.

Family Level

The client was raised to conform to his father’s expectations and was never allowed to explore and develop according to his individual and unique characteristics. As he grew older, the mother became more enmeshed and the father became too rigid in terms of his expectation from the client. The client tried to individuate from his family of origin by making decisions in terms of his career, friends, or hobbies. He was not supported for making those choices, and disapproval was shown through criticism and hostility, mostly by father, as he was the leader of the family and the primary decision maker. When the client was not able to cope up with the father’s behavior, he acted out by dissociating. Whenever he would dissociate, he was able to stand for himself and confront his father. The client learned to use dissociation as a defense mechanism from his mother, who was using it to cope up with marital discord, which was mostly due to differences in parenting styles. The power structure within the family was gender specific, and the client’s mother was expected by the client’s father to perform her roles and responsibilities without voicing her opinion. She desired more emotional support from the father, who was unable to understand the need for more communication and closeness towards the mother. Both the parents failed to understand that differences in parenting they need to be more sensitive to the client who was struggling to individuate and develop his own identity.

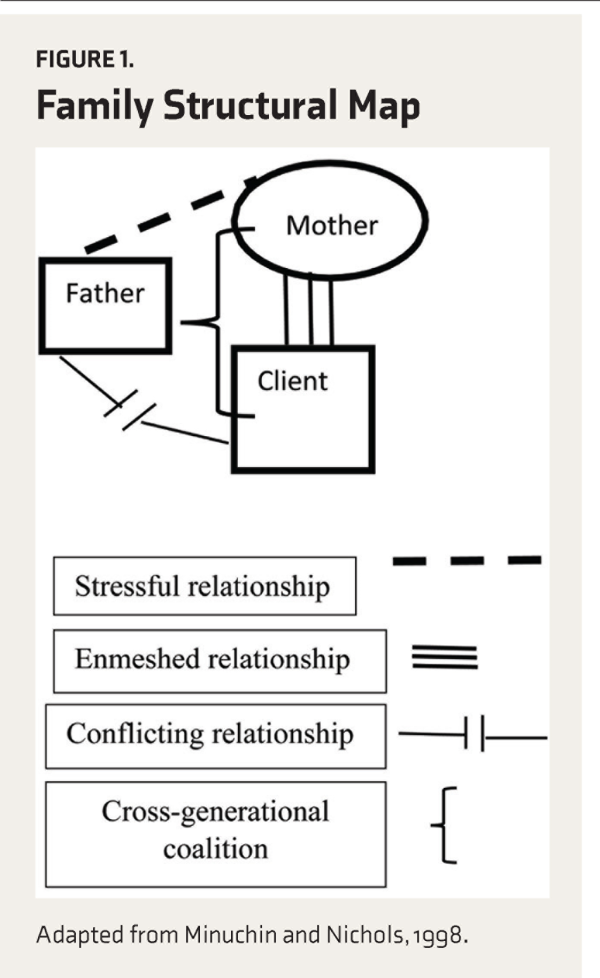

Family Mapping (Figure 1)

This map was drawn to understand the family’s structure. The map showed that there is a cross-generational coalition between the client and the mother against the father, which had resulted in a conflict between the father and the client, a strenuous relationship between the father and the mother, as well as an enmeshed relationship between the client and the mother.

Figure 1

Family Structural Map

Adapted from Minuchin and Nichols, 1998.

Stage 4: Goal Setting

The intervention with the client focused on achieving the following goals: (a) to intervene in the faulty attachment pattern; (b) to help the client to develop a cohesive, unified personality and enhance his coping skills; (c) to make the client more assertive in a relationship; and (d) to restore the client’s functioning.

The intervention with the family focused on the following: (a) to psychoeducate the family about dissociation and (b) to address interpersonal issues within family members and restructuring boundaries around various subsystems (couple, parents, and parent–child).

The expected outcome of the intervention was to improve the client’s functioning and to make the family more cohesive by discussing the developmental issues with the family.

Stage 5: Interventions

Individual Level

Intervention Plan

Interventions focused on building trust and rapport with the client, stabilizing him, and then helping him to accept the altered personality and to work on affect regulation by enhancing his coping skills. Treatment also centered around making him more assertive in a relationship and improving his overall functionality. Eleven sessions were taken with the client to work on these aspects of interventions. Booster sessions may be provided on an outpatient basis to help the client to adjust to a new, integrated personality.

Interventions followed guidelines given by the International Society for the study of Trauma and Dissociation.

Process of Interventions

Assessment and feedback of client’s attachment pattern: The client had a disorganized attachment with the father as the father was not able to be emotionally available and had high expectations from the client and was quite controlling by nature. He had a secure attachment with the mother as she met his emotional and individual needs for care and support. Feedback was given to the client about how the insecure attachment with the father affected the client’s way to self-soothe himself during a stressful situation, and that whenever the client dissociated, he was able to stand for himself and confront his father.

Developing a cohesive, unified personality and enhancing coping skills: The therapist educated the client on how a person, when exposed to severe and prolonged stress, is not able to cope up with it. As a result, the splitting of the personality occurs. Splitting is a response to changes in the emotional state due to environmental stress, which results in another identity emerging to take control. The therapist discussed with the client more adaptive ways of solving a problem and to remember, tolerate, process, and integrate overwhelming past memories. Through therapy, the client learned his and others’ roles in the occurrence of traumatic events. As traumatic memories were integrated, the alternate identity appeared less and less separate and distinct.

The therapist also discussed with the client ways to enhance his coping skills. Suggested techniques at the physiological level were focused breathing and engaging in coping self-talk. At the behavioral level, he was advised to practice attentionshifting tasks like watching TV or playing games, listening to music, and involving in other pleasurable activities. In the long term, emphasis was given to identifying a problem and working on it by using steps involved in problem-solving.

Assertiveness Training: It focused on helping the client to be more assertive in a relationship. The client was encouraged to make more use of “I statements” to express his opinion. Through role-play, he was made to practice the technique of broken record, which was to be persistent and stick to the point of discussion. Role-play also helped the client to realize the importance of maintaining the tone of voice, gestures, eye contact, facial expression, and posture while talking to others. The therapist discussed with the client how he needs to focus on the father’s specific behavior and communicate to his father how his behavior was affecting the client and what specific changes he wants in his father’s behavior.

Activity scheduling: The client had depressive symptoms, which affected his day-to-day routine as well. Therefore, there was a need to monitor, schedule, and maximize the client’s engagement in mood-elevating activities. The activity schedule started with a short-term goal. The goal was to introduce small changes, building up the level of activity gradually towards long-term goals. Different types of positive reinforcers and basic rules of giving positive reinforcement were discussed with the parents. Some of the activities given were going for a walk, making a new friend, playing badminton in the evening, and maintaining a diary.

At Family Level

Intervention Plan

It focused on building rapport, joining the family, understanding how boundaries were created within the relationship, making the boundaries permeable, restructuring relationship hierarchies, and addressing developmental issues within the family. All these aspects of interventions were addressed by taking 12 sessions with the family. Booster sessions can be provided to the family on an outpatient basis to maintain therapy gains and prevent relapse.

Interventions followed guidelines given by the Minuchin Centre for the Family.–

Process of Intervention

Psychoeducation about dissociation: Parents were educated about how the client was using dissociation as a defense mechanism to cope with relationship difficulty with father and how he was getting secondary gain by dissociating, in the form of parental attention and father’s affection and support, which were not there normally.

Structural family therapy

Accommodating and joining the family

The therapist aligned with the family by using the technique of “mimesis,” which helped in imitating the style and content of the family’s interaction pattern to reflect the problems within the communication patterns.

Changes in subsystem

Couple subsystem: The couple was encouraged to share their feelings and emotions by making use of “I statements” and to communicate their feelings even if it appears distasteful. In order to make the couple develop ability to listen to each other, they needed to acknowledge what they say to each other, without criticizing, interrupting, or attacking and communicate back their understanding of what the partner was saying. They needed to avoid abstract form of statements that were not clearly communicating what they wanted to say. The couple was asked not to use critical statements like “you never support me” or “you always behave like this.” Such statements will make the person feel accused; so they will not hear the request for change and will instead be defending themselves.

Parent subsystem: The therapist discussed with the parents the need to adopt an authoritative parenting style by being consistent in enforcing boundaries and by being more empathic in recognizing and responding to the client’s needs. Parents were also asked to encourage the client for direct expression of thoughts and feelings, without reinforcing dysfunctional dissociative strategies (e.g., giving him more positive attention and selective reinforcement when he was not dissociating).

Parent–Child subsystem: The therapist informed the parents that they need to learn to negotiate with the client by making him see the pros and cons of his behavior and that they should set limits with positive and negative consequences for his behavior. They can encourage the client to start taking up certain household responsibilities and make minor decisions in his day-to-day life, which will initiate the process of separation-individuation.

Changes in the interaction pattern

There was a need to relabel the interaction between the family members in positive terms and reduce the scapegoating of the client by the father. The techniques used were:

Positive reframing: The therapist chose different words and phrases to identify and positively label the family’s problems.

Enactment: The family members were asked to review the enacted incident step by step, and to describe the reactions of each family member involved in the incident. The therapist also gave feedback about the problematic dynamic that took place, in the form of how they interacted with each other during the incident and how they can improve communication. The therapist also appreciated the family members for taking the feedback of the therapist in a positive way.

Unbalancing: For most of the sessions, the therapist tried to change the hierarchal relationship of the parent–child subsystem by siding with the client who had less power and status within the family, which also affected the family’s homeostasis. The therapist tried to change pre-existing family interaction patterns by first unbalancing the client’s father and then realigning the system. The therapist refocused his attention on the client and the client’s feelings, needs, intentions, strengths, and abilities.

Predischarge counseling: In predischarge counseling, the previous sessions were summarized. The therapist focused on helping the parents identify the client’s early warning signs, for seeking help immediately. The therapist highlighted the need for continuing medicines postdischarge to control depressive symptoms.

Stage 6: Termination

The therapist addressed the client’s and family’s feelings, concerns, and anxieties related to the termination and explored the anticipated challenges that might lead to a setback in the future and how they can handle those difficulties. Throughout the therapy, the therapist placed the responsibility of change on the client and family, so that they do not become dependent on the guidance of the therapist. Termination of therapy was mutually decided by the client, family, and therapist once the therapeutic goals were attained. Therapist informed client and family about the option of receiving telephonic follow-ups and booster sessions, if required, in the future, which can be planned on outpatient basis for a long-term maintenance of treatment gains.

Outcome of Therapy

Individual therapy helped the client’s inner self to become less fragmented, which also helped him to become calmer and improved his interpersonal functioning and coping skills.

Family therapy helped the parents understand under what circumstances the client was dissociating and how the changes in the family dynamics helped the client to develop a cohesive and integrated personality. Parents became aware of the symptoms and how to handle them during future crisis situations.

Discussion

Minuchin recognized that change within the family is normal and inevitable, but how a family adapts to those changes will decide whether the family is functional or dysfunctional. The changes in the client’s family came when he tried to individuate by taking decisions in terms of his career, friends, or hobbies. He was not supported for making those choices, and disapproval was shown through criticism and hostility, mostly by father. If we see the client’s situation from the perspective of Margaret Mahler’s separation-individuation theory, which states that as a child tries to develop a separate sense of self and identity as they grow up, it may not be allowed and accepted by the parents, who can often induce in the child a sense of guilt, shame, or fear. It may affect the child’s confidence, and the child may feel hesitant to express himself/herself in front of others because of self-doubts and uncertainties, which often results in anxiety, depression, and social isolation in the child’s later life. Therapy helped the client to accept negative feelings such as the feeling of being let down or rejected, anger, and frustration, and to build his capacity to modulate those feelings and thus handle them appropriately. Kluft states that interventions for persons with DID should focus on achieving optimal cohesiveness and integration of the altered identities so that the person can have adequate emotional, interpersonal, and occupational functioning, which was achieved through interventions in the client’s case.

Stressful family environments can promote the development of dissociative disorder. In this case, the client learned to dissociate by modeling his mother, who used it as a defense mechanism to cope up with interpersonal conflict with the client’s father. Mann and Sanders state that if a parent has dissociation, a child may have a tendency to dissociate because of genetic vulnerability and modeling of the behavior. Parents’ rejection and child dissociation are also related, which can be explained by the psychodynamic theory, which states that the child strongly tries to identify with the rejecting parent in order to regain his or her love. The client’s mother reported that whenever the client disassociated, he behaved like his father—authoritative and critical. Luxton believed that inconsistency in parenting in terms of giving positive reinforcement and setting consequences of behavior could negatively affect a child’s sense of self-worth or self-esteem, which happened with the client as well. According to Pais, in such cases, intervention with family should focus on helping the family understand the need to provide a safe and secure environment that can help persons with DID to re-experience trauma without feeling guilty and shameful. By doing so, a person with DID will be able to cope up with the splitting of personality without indulging in self-injurious and homicide behavior, which was the outcome of intervention with the family in this report.

Treatment Implication of the Case

In persons with DID, frequent dissociation can lead to comorbid conditions like anxiety, depression, suicidal thoughts, and self-injurious behavior, resulting in a long-term course of treatment. Medications like antidepressants or anxiolytics are prescribed for comorbid conditions; they do not specifically treat the dissociation. Psychotherapy, which has been effective in such cases, needs to be eclectic in approach, focusing on providing supportive or crisis interventions, enhancing coping skills, and making the clients aware of the dissociated aspect of self, helping them to accept and integrate it into their personality.

SFT is a powerful model for working with persons with DID and their families. It is based on the basic principle that the client’s problem can be understood and treated in the family context. The effectiveness of SFT has also been seen in psychosomatic illnesses, eating disorders, drug abuse, and borderline personality disorder.

Barriers and Challenges to the Case Management

Limitations of the Case Study

The authors of this article were the primary therapists, which may have led to experimenter bias. To lessen the possibility of bias, the article was written after the therapy was concluded. Secondly, this case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case, so it cannot be generalized to all the adult clients with dissociation, as a difference in client characteristics, family context, and the therapeutic relationship may have affected the outcome of the study.

Limitations of the Therapy

Family therapy can bring intense discomfort in persons with DID by bringing back traumatic memories of the conflict with other family members, which can be counterproductive to the therapeutic progress. Therefore, before starting the sessions, it is important to clinically prepare the client to handle the session and to prevent revictimization. It is important to assess domestic violence in all clients who come for family therapy as it would affect the course and outcomes of the therapy. Babcock et al. reported that severe domestic violence may be a contraindication for SFT as the focus would shift from changing the family functioning to addressing more immediate concerns like safety planning. When educating the clients about dissociation, they may resist accepting altered identities as part of self, so it is important to build trust and a sense of safety within the therapeutic relationship and to discuss negative transference that may arise during those discussions. The therapist should not side with or outrightly reject the viewpoint of any altered identity but should be emphatic, validating, and flexible and use language that is accepting of all the identities of the client.

Recommendations

It is important to research and see the applicability of SFT with individual clients who are at different life cycle stages (e.g., adolescent, adulthood, or old age). To bridge the gap in the research on the effectiveness of different models of family therapy, it is important to apply SFT techniques on more individual clients and compare the effectiveness with that of other systemic models such as Bowenian. There is also a need to do a long-term follow-up study to see the effectiveness of SFT techniques on individual clients with different types of psychiatric illnesses.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Hartman D. An overview of the psychotherapy of dissociative identity disorder. J Heart Cent Therap 2010(13): 29–30.

- 2. Ross CA. Dissociative identity disorder: Diagnosis, clinical features, and treatment of multiple personality. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 1997.

- 3. Bailey TD, Brand BL. Traumatic dissociation: Theory, research, and treatment. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 2017; 24(2): 170–185.

- 4. Kluft RP, Donne J. Treatment of multiple personality disorder: A study of 33 cases. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1984; 7(1): 9–29.

- 5. Nichols MP. Family therapy: Concepts and methods. Boston, MA: Pearson Higher Education; 2012

- 6. Minuchin S, Nichols MP, Lee WY. Assessing families and couples: From symptom to system. Boston, MA: Pearson Allyn and Bacon; 2006.

- 7. Minuchin S, Fishman HC, Minuchin S. Family therapy techniques. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1981.

- 8. Meyer GJ, Finn SE, Eyde LD, . Psychological testing and psychological assessment: A review of evidence and issues. Am Psychol 2001; 56(2): 128.

- 9. International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation. Guidelines for treating dissociative identity disorder in adults, third revision: Summary version. J Trauma Dissociation 2011; 12(2): 188–212.

- 10. Minuchin S, Fishman HC, Minuchin S. Family therapy techniques. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1981.

- 11. Fishman HC. Intensive structural therapy: Treating families in their social context. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1993.

- 12. Fishman HC. Treating troubled adolescents: A family therapy approach. London: Routledge; 2017.

- 13. Bergman A. Merging and emerging: Separation-individuation theory and the treatment of children with disorders of the sense of self. J Infant Child Adolesc Psychother 2000; 1(1): 61–75.

- 14. Edward J, Ruskin N, Turrini P. Separation/individuation: Theory and application. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 1992.

- 15. Kluft RP. Clinical perspectives on multiple personality disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 1993.

- 16. Mann BJ, Sanders S. Child dissociation and the family context. J Abnorm Child Psychol 1994(22): 373–388.

- 17. Schimmenti A. The developmental roots of dissociation: A multiple mediation analysis. Psychoanalytic Psychol 2017; 34(1): 96.

- 18. Luxton DD. The effects of inconsistent parenting on the development of uncertain self-esteem and depression vulnerability. PhD Thesis, University of Kansas, USA, 2007

- 19. Pais S. A systemic approach to the treatment of dissociative identity disorder. J Fam Psychother 2009(20): 72–88.

- 20. Gentile JP, Dillon KS, Gillig PM. Psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for patients with dissociative identity disorder. Innov Clin Neurosci 2013; 10(2): 22.

- 21. Stern TA, Fava M, Wilens TE, . Massachusetts general hospital comprehensive clinical psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015.

- 22. Combrinck-Graham L. Structural family therapy in psychosomatic illness: treatment of anorexia nervosa and asthma. Clin Pediatr 1974; 13(10): 827–833.

- 23. Fishman HC. Enduring change in eating disorders: Interventions with long-term results. New York, NY: Routledge; 2005.

- 24. Sim T. Structural family therapy in adolescent drug abuse: A Hong Kong Chinese family. Clinical Case Studies 2007; 6(1): 79–99.

- 25. James AC, Vereker M. Family therapy for adolescents diagnosed as having borderline personality disorder. J Fam Ther 1996(18): 269–283.

- 26. Babcock JC, Green CE, Robie C. Does batterers’ treatment work? A meta-analytic review of domestic violence treatment. Clin Psychol Rev 2004; 23(8): 1023–1053.