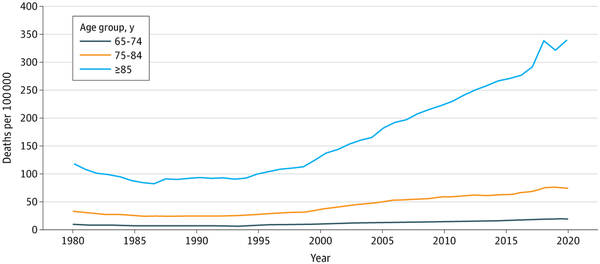

In 2023, more than 41 000 individuals older than 65 years died from falls. Among older adults, the number of deaths from falls is more than from breast or prostate cancer and is more than from car crashes, drug overdoses, and all other unintentional injuries combined. More importantly, the mortality rate for falls among older adults in the US has more than tripled during the past 30 years (Figure). In contrast, death rates due to falls decreased during the past 30 years in other high-income countries.

Figure

Mortality Rates From Fall Injuries by Age Group Among Older Adults in the US, 1980-2023

Data are from the National Center for Health Statistics, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Older adults have always been at risk for falls. A fall injury results from a confluence of intrinsic and extrinsic risks. In addition to older age, risk factors for fall injuries include physical impairment (such as muscle weakness, balance problems, or difficulty walking), vision problems, cognitive impairment, use of alcohol or drugs, living alone, and a home littered with objects that can be tripped over. These falls can sometimes be fatal (eg, if they lead to a major head injury or a hip fracture that starts a downward spiral).

The surge in deaths from falls in the US reflects a new phenomenon. There is no reason to think that older adults today are much more likely to be physically frail, have dementia, have cluttered homes, or drink alcohol and use drugs than age-matched adults 30 years ago, and the percentage living alone has not changed much since 2000. On the other hand, there is plenty of reason to believe that the surge in fall deaths may be tied to the soaring use of certain prescription drugs, which is a risk factor that, unlike most other factors, clinicians can readily modify.

Older adults in the US are heavily medicated. From 2017 to 2020, 90% of adults older than 65 years were taking prescription drugs, 43% were taking multiple prescription drugs, and 45% were taking prescription drugs that were “potentially inappropriate.”

Drugs that cause drowsiness or impaired balance or coordination have been called fall risk–increasing drugs (FRIDs). The list of FRIDs is long and includes drugs such as β-blockers and anticholinergics, as well as proton pump inhibitors that may increase the risk of an injury during a fall. A systematic review found that 65% to 93% of older adults injured from falls were taking at least 1 FRID at the time, and many were taking more than 1 FRID.

Four categories (opioids, benzodiazepines, gabapentinoids, and antidepressants) of central nervous system–active FRIDs are particularly concerning because of a combination of surging use and a strong association with falls. Increased opioid prescribing in the US began in the early 1990s and coincides with the rise in fall deaths. The prescribing of benzodiazepines increased in the 2000s, as did the number of older adults receiving prescriptions for the particularly dangerous combination of opioids and benzodiazepines. Nearly 20% of people older than 85 years were prescribed benzodiazepines by physicians at outpatient clinics for the 2009-2010 period. Since about 2012, the prescribing of opioids and benzodiazepines to older adults has decreased, but these drugs are still heavily prescribed.

In the 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 32% of adults older than 65 years had taken prescription pain relievers (most of which are opioids) and 17% had taken prescription tranquilizers or sedatives (most of which are benzodiazepines) at some point during the previous year. With reduced prescribing of opioids, gabapentinoids are frequently prescribed off-label for chronic pain. Between 2006 and 2018, prescriptions for gabapentin and for combinations of gabapentin and opioids increased approximately 4-fold. And between 1999 and just before the COVID-19 pandemic, the percentage of older adults (>65 years of age) taking antidepressants increased from 8% to 20%.

This prescribing is occurring despite warnings from the American Geriatrics Society about the fall risks associated with these drugs. The American Geriatrics Society strongly recommends that physicians avoid prescribing benzodiazepines and many antidepressants to older adults and strongly recommends against prescribing combinations of opioids and either benzodiazepines or gabapentinoids.

It is hard to medically justify the current levels of prescribing of central nervous system–active FRIDs to older adults. Opioids are no more effective than the safer drugs for treatment of most types of pain. Benzodiazepines cannot possibly be needed by nearly 20% of 85-year-old individuals when experts recommend that they not be used at all. Some older adults have severe depression and benefit from antidepressants, but it is hard to imagine that is true for 1 in 5.

More research is needed to better understand the relative importance of different FRIDs in causing fall deaths. But clinicians should not wait for this research to reduce their prescribing of risky drugs to older adults. Physicians should review the medications of their older patients and stop prescribing drugs that are unnecessary or dangerous. Unfortunately, physician medication reviews have not reduced falls, perhaps because the clinicians who prescribed the medicines are reluctant to discontinue them.

A more organized, broader effort is needed to stop inappropriate and dangerous prescribing to older adults. Most physicians and other health professionals with prescribing authority are affiliated with large health systems that use electronic health records. It should not be difficult for these health care systems to identify patients older than 65 years receiving FRIDs and provide feedback to the prescribing clinicians. The health care system feedback for clinicians could include summarizing data on their FRID prescribing, offering advice on alternative safer treatments, or adding FRID use as an incentivized quality-of-care metric.

The more than tripling of deaths due to falls in recent years suggests that at least two-thirds of these deaths (>25 000 each year) can be prevented. It is time for organized medicine to take this problem seriously and act to save lives.

References

- 1. National Center for Health Statistics, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Underlying cause of death data on CDC WONDER. Accessed June 30, 2025. https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html

- 2. Kim S, Kim S, Woo S, et al. Temporal trends and patterns in mortality from falls across 59 high-income and upper-middle-income countries, 1990-2021, with projections up to 2040: a global time-series analysis and modelling study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2025;6(1):100672. doi:10.1016/j.lanhl.2024.100672

- 3. Innes GK, Ogden CL, Crentsil V, Concato J, Fakhouri TH. Prescription medication use among older adults in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2024;184(9):1121–1123. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2024.2781

- 4. Hart LA, Phelan EA, Yi JY, Marcum ZA, Gray SL. Use of fall risk-increasing drugs around a fall-related injury in older adults: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(6):1334–1343. doi:10.1111/jgs.16369

- 5. Agarwal SD, Landon BE. Patterns in outpatient benzodiazepine prescribing in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e187399. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7399

- 6. Marra EM, Mazer-Amirshahi M, Brooks G, van den Anker J, May L, Pines JM. Benzodiazepine prescribing in older adults in US ambulatory clinics and emergency departments (2001-10). J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(10):2074–2081. doi:10.1111/jgs.13666

- 7. SAMHSA (Substance Use and Mental Health Services Administration). 2023 NSDUH (National Survey on Drug Use and Health) detailed tables. Published July 30, 2024. Accessed February 24, 2025. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2023-nsduh-detailed-tables

- 8. Peet ED, Dana B, Sheng FY, Powell D, Shetty K, Stein BD. Trends in the concurrent prescription of opioids and gabapentin in the US, 2006 to 2018. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(2):162–164. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.5268

- 9. 2023 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2023 updated AGS Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(7):2052–2081. doi:10.1111/jgs.18372

- 10. Chou R, Wagner J, Ahmed AY, et al. Treatments for Acute Pain: A Systematic Review. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. doi:10.23970/AHRQEPCCER240