Introduction

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) has been used to collect global health data and statistics for over a century. ICD-11 became the latest official version as of January 2022. Over 35 countries are already using the ICD-11 for causes of death, primary care, cancer registration, and reimbursement, among others. Member countries of the World Health Organization (WHO) are mandated to report annual mortality statistics in ICD according to the WHO Constitution and Nomenclature Regulations and provide morbidity reporting for international statistical use. SNOMED CT is the most comprehensive, multilingual clinical healthcare terminology in the world. Membership of SNOMED International has grown from 9 founding member countries in 2007 to 48 in 2023. SNOMED CT is in use in more than 80 countries.

In most countries, SNOMED CT and ICD are both in use for various purposes. Being a clinical terminology, SNOMED CT is generally considered more useful in the support of clinical documentation and patient care. As a medical classification, the use of ICD is more often related to reimbursement, health services reporting, and population health statistics. However, significant overlap exists in the use of the 2 coding systems. In most use cases, examples can be found that use one or the other. Questions have been raised about whether 2 distinct, yet overlapping, coding systems are needed. Based on the different purposes, design, characteristics, use cases, and actual usage of the 2 coding systems, it is unrealistic to expect that either one alone will be sufficient for all purposes. It is likely that both will continue to exist and be used. The parallel use of SNOMED CT and ICD raises several issues. First, there is apparent duplication of effort in developing and maintaining 2 coding systems with considerable overlap in their content, especially in the domain of diagnosis, findings, and disorders. From the perspective of the member countries of both SNOMED International and WHO, this may come across as if they are funding 2 duplicative systems. Curation of content often draws on the voluntary contribution from the same pool of clinical experts. Moreover, international use of the 2 coding systems often requires independent, separate efforts in language translation. Generating data encoded in 2 separate systems requires duplicative effort in coding. Furthermore, the value of the coded data may be lessened if the 2 data streams cannot be meaningfully integrated.

One potential solution to some of the above problems is to make SNOMED CT and ICD interoperable. As early as 2010, SNOMED International and WHO have entered into collaborative arrangements with the ultimate goal of enabling users to use SNOMED CT and ICD jointly and interoperably. The initial focus was on providing a map from SNOMED CT to ICD-10, the official version of ICD back then. Such a map could mitigate the problem of duplicate coding effort by leveraging SNOMED CT encoded data to generate ICD-10 codes in an automatic or semi-automatic manner. The map could also facilitate the integration of data coded separately in SNOMED CT and ICD-10. More importantly, the agreement also set out a framework for linking SNOMED CT and ICD-11 that was still under development.

With the innovative features introduced in the development of ICD-11,, new possibilities arise for the alignment with SNOMED CT. One brand new feature of ICD-11 is the Foundation component. The ICD-11 Foundation is a rich knowledge base that holds all necessary information to generate lists of classification codes (called “linearizations”) needed for various purposes. The analogy is that the Foundation is a deep sea of terms and meanings, where a subset of the most common or important terms will appear “above the shoreline” in the linearizations. Multiple linearizations for different purposes and settings can be generated from the same Foundation, which are fully compatible and interoperable. The principal linearization of ICD-11 is called the MMS (ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics), which replaces ICD-10 as the main coding system. The ICD-11 Foundation is inherently more similar to a terminology than a classification, and it does not have requirements such as single inheritance and residual categories (eg, unspecified, not elsewhere classified). This introduces the possibility of aligning SNOMED CT and ICD-11 using ontological formalisms. In the 2010 Memorandum of agreement, SNOMED International and WHO agreed that SNOMED CT would be used as the joint ontology for the ICD-11 Foundation. However, that pursuit was later halted. While there was no official explanation of the decision not to use SNOMED CT, it was believed that the following factors might be involved: underestimation of the time and effort in coordination and approval of changes, copyright and intellectual property issues, and the time constraint of delivering ICD-11. Despite this, efforts to make SNOMED CT and ICD-11 interoperable have continued. There was an initial project to harmonize SNOMED CT and the ICD-11 MMS, which led to the addition of many new concepts in SNOMED CT to facilitate a map from SNOMED CT to ICD-11 MMS. There was also a pilot to explore automated mapping between SNOMED CT and ICD-11, resulting in the publication of a draft map for preview in 2021. From September 2021 to August 2022, SNOMED International and WHO undertook a pilot project to create 2 maps, one in each direction, between SNOMED CT the ICD-11 Foundation. This report describes the methods, findings, and lessons learned from this pilot project.

Materials and methods

SNOMED International and WHO collaborated to conduct a mapping pilot between SNOMED CT and ICD-11 Foundation in both directions. The objectives included:

Establish a collaborative process through which the mapping could be achieved.

Identify early challenges and attempt to provide recommendations for resolution.

Progress the mapping of the subset and usage validation as far as possible in the time available.

Recommend the mapping development and quality assurance approach and transparent issues handling process for the more comprehensive mapping exercise between SNOMED CT and ICD-11.

Identify recommendations for review of SNOMED CT and/or ICD-11 content to promote alignment.

Explore and elaborate best practices for the mapping, taking into account WHO mapping guidance and other available documentation.,

The pilot was carried out in 2 phases:

Phase 1 (September 2021–January 2022)—mapping from ICD-11 Foundation to SNOMED CT

Phase 2 (February 2022–August 2022)—mapping from SNOMED CT to ICD-11 Foundation

Use cases of the maps

The summary use case for both phases was establishing links between ICD-11 Foundation and SNOMED CT, enabling primary documentation in either system with no semantic meaning loss.

For the ICD-11 Foundation to SNOMED CT map (phase 1), the map must support an exact match translation from the ICD-11 Foundation to SNOMED CT. This supports semantic interoperability and assists vendors and healthcare providers in exchanging primary data coded in ICD-11 and SNOMED CT, respectively (without risks for potential change or loss of meaning or detail), which is safe and fit for use.

The SNOMED CT to ICD-11 Foundation map (phase 2) is, as phase 1 and additionally, to ensure data consistency for the mandatory recording and reporting with ICD-11 internationally in line with the WHO guidelines, by the identification of equivalent translations from SNOMED CT to ICD-11.

Materials

For phase 1, ICD-11 Foundation entities belonging to Chapter 5 Endocrine, nutritional or metabolic diseases were in scope, focusing on endocrine diseases. Note that malignant neoplasms were not included since they belonged to a separate chapter in ICD-11. This comprised 637 (0.8%) ICD-11 Foundation entities, each identified by a unique resource identifier (URI). To identify SNOMED CT concepts for phase 2, we analyzed the target SNOMED CT concepts used in phase 1 and found that almost all were from the Clinical Findings hierarchy. Therefore, we used all descendants of the SNOMED CT concept 362969004 Disorder of endocrine system, except those that were also descendants of 363346000 Malignant neoplastic disease, as concepts to map in phase 2, comprising 1893 (0.5%) SNOMED CT concepts.

Mapping methodology

Mapping was undertaken by volunteers who are terminology and classification experts. A dual independent mapping approach was adopted—each map was created independently by 2 mappers, results compared, and any discrepancy was discussed until consensus was reached. Online browsers used included the SNOMED CT International browser (both the public browser and the Daily Build browser to access the latest new content), the ICD-11 Foundation browser, and the ICD-11 coding tool. Biweekly online meetings were held. Guidelines for mapping were initially developed based on the first 120 cases, and subsequently modified and refined as required.

The primary goal of mapping was to identify equivalence between the meaning of an ICD-11 Foundation entity and a SNOMED CT concept. The mapping team adopted a strict definition of equivalence (exact map or exact match), and all doubtful or marginal cases would be flagged as non-equivalent (see Results for examples).

In phase 1 of mapping from ICD-11 Foundation entities to SNOMED CT, we decided that postcoordination would not be used in SNOMED CT. Even though SNOMED CT supports postcoordination, we believed that since SNOMED CT concepts are generally more fine-grained than ICD-11 entities, there would be less need in SNOMED CT for postcoordination, which is most useful in adding details to existing concepts. In the set of 120 test cases examined at the start of the project, none of the SNOMED CT targets required postcoordination. Therefore, we decided that postcoordination would not be used in SNOMED CT.

Postcoordination (or “code clustering” in WHO parlance) in ICD-11 was used in phase 2 when mapping from SNOMED CT to ICD-11. We believed that ICD-11 was designed to be used with postcoordination, and that it would help to improve matching with SNOMED CT concepts. The ICD-11 coding tool provides options and restrictions to guide postcoordination where applicable, but not all clinically meaningful options are included. In the pilot project, unlisted postcoordination combinations were allowed if they followed the same general pattern of the allowable options and a suitable extension code existed. As an example, for the SNOMED CT concept 235978006 Cystic fibrosis of pancreas, exact match could be achieved by combining the ICD-11 Foundation entity Cystic fibrosis with the extension code Pancreas. This combination was allowed in the pilot project even though it was not available in the coding tool. Note that after the conclusion of the pilot project, WHO has added “Other postcoordination” to the ICD-11 browser to allow combinations beyond the displayed options. In phase 1, only exact maps were recorded. In phase 2, for cases without an exact map, the closest matching ICD-11 entity was identified and labelled as broader, narrower, or partial overlap in relation to the SNOMED CT concept. In both phases, for cases without an exact map, an attempt would be made to identify the possible editorial changes in either SNOMED CT or ICD-11 that would result in an exact map.

Results

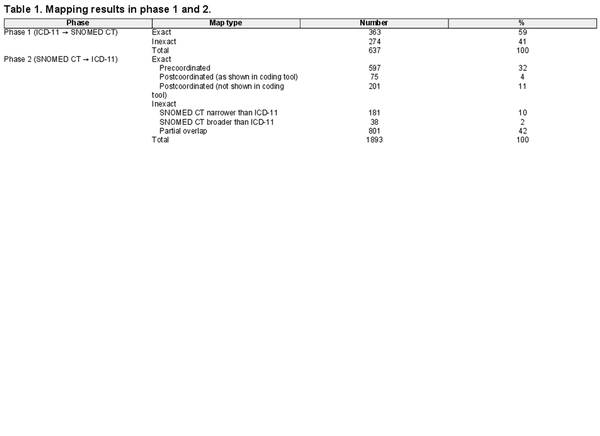

The results of mapping are summarized in Table 1. In phase 1, among 637 ICD-11 Foundation entities, 59% had exact matches in SNOMED CT. In phase 2, among 1893 SNOMED CT concepts, 32% had exact match with a single pre-coordinated Foundation entity. Postcoordination within the coding tool found an additional 4% of exact match. Allowing postcoordination options not shown in the coding tool further increased exact match by 11%.

For cases without exact maps, sometimes possible actions could be suggested to achieve exact maps. These actions generally fall under 4 categories:

Non-synonymous “synonyms”

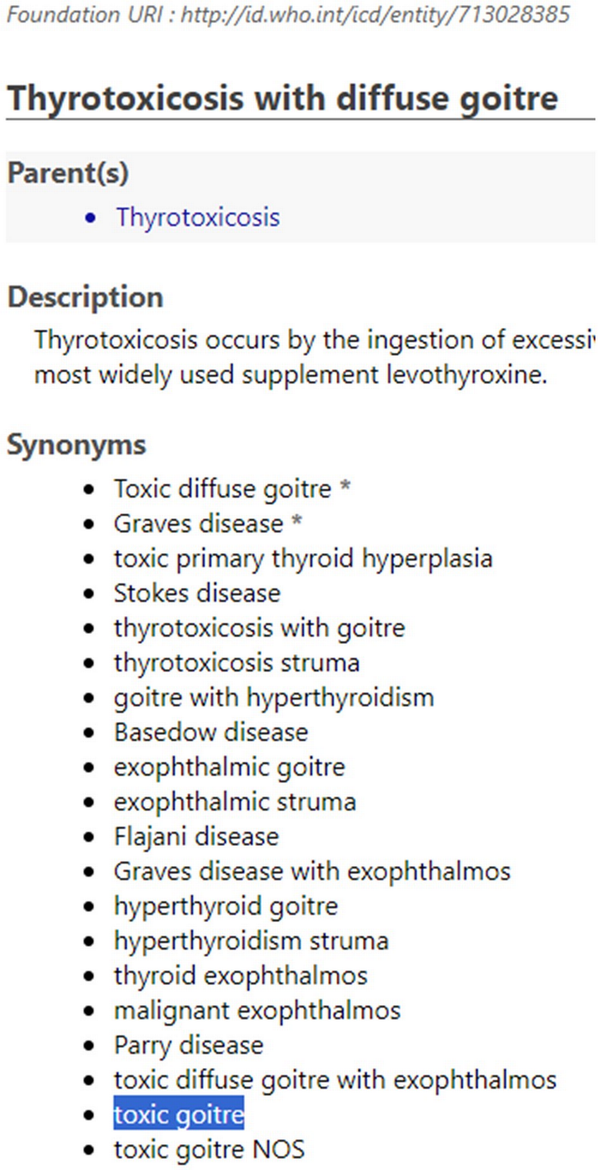

There was a dubious synonym in either SNOMED CT or ICD-11, which was the basis of matching, but that synonym was not considered to be exactly synonymous. This problem was more often encountered on the ICD-11 side. As an example, for the SNOMED CT concept 237498007 Toxic goiter, there was a lexical match with the synonym Toxic goiter under the ICD-11 Foundation entity Thyrotoxicosis with diffuse goiter (Figure 1). However, since toxic goiter can be either diffuse or nodular, Toxic goiter is broader in meaning than Thyrotoxicosis with diffuse goiter and not exactly synonymous. Therefore, Thyrotoxicosis with diffuse goiter was not considered an exact map for the SNOMED CT concept. It was suggested that the non-synonymous synonym Toxic goiter should become a separate, broader entity that subsumes Thyrotoxicosis with diffuse goiter. The new entity Toxic goiter would then be an exact map for the SNOMED CT concept. It was estimated that about 100 (5%) more SNOMED CT concepts in phase 2 would have exact maps in this way.

Mismatch in granularity

This problem can be separated into 2 types:

Missing grouper condition—eg, for the SNOMED CT concept 266589005 Endometriosis of ovary, there was no exact match in ICD-11 Foundation, which only had Superficial ovarian endometriosis and Deep ovarian endometriosis. The suggestion was to add a grouper entity Ovarian endometriosis.

Missing specific condition—eg, in SNOMED CT, 80193009 Postgastric surgery syndrome (with synonym: Dumping syndrome) had 2 children: 235666009 Early dumping syndrome and 235667000 Late dumping syndrome. In ICD-11 Foundation, only Dumping syndrome was available. It was suggested that Early dumping syndrome and Late dumping syndrome should be added as Foundation entities.

Composite conditions

These are cases in which multiple conditions are involved. Some examples in ICD-11: Congenital hypothyroidism due to iodine or sodium symporter mutations, Primary congenital hypothyroidism due to TSH receptor mutations, Hypoglycaemia in the context of diabetes mellitus without coma; in SNOMED CT: 367741000119106 Diffuse thyroid goiter without Thyrotoxicosis, 102871000119101 Hypothyroidism due to thyroiditis, 26572003 Polyglandular dysfunction AND/OR related disorder. The component parts of the composite conditions are often joined by operators indicating causation (“due to”), disjunction (“or”), conjunction (“and”), negation (“without”), or other relationships. The semantics of these operators are not always clearly defined, their use may be different in SNOMED CT and ICD-11, and sometimes their meaning can be ambiguous. It was suggested that SNOMED International and WHO should work on a clear and harmonized definition of these operators so that guidelines could be established in the modeling and mapping of these composite conditions.

Residual categories

The ICD-11 Foundation is intended to function as a terminological knowledgebase rather than a classification. This means that some requirements of a classification, such as single-parenting and residual categories (eg, other, not elsewhere classified, unspecified) do not apply to the Foundation. However, some Foundation entities were found which resembled residual categories, eg, Certain specified disorders of parathyroid gland; Diabetes mellitus due to other genetic syndromes; Hypoglycaemic reaction, not elsewhere classified; Diabetes mellitus, type unspecified. These cases are problematic because it is generally not possible to have an exact map between a concept in a terminology (such as SNOMED CT) and a residual category. It was suggested that WHO should review these cases and clarify whether they are indeed intended to be in the Foundation.

Figure 1

Non-synonymous “synonym” for the ICD-11 Foundation entity Thyrotoxicosis with diffuse goiter.

Symmetry of the maps

The phase 1 and phase 2 maps were covering essentially the same conditions, the only difference was the direction of mapping. For exact (equivalent) matches, it is expected that the same pair of codes would be found, regardless of the directionality of the map, ie, that the maps would be “symmetrical”. In phase 1, 363 ICD-11 Foundation entities had exact match to 345 distinct SNOMED CT concepts (there were some cases of 2 ICD-11 entities mapping to the same SNOMED CT concept), among which 267 SNOMED CT concepts were used as source codes to map to ICD-11 in phase 2. For these 267 concepts, 227 (82.5%) were mapped to the same ICD-11 entity as in phase 1 (symmetrical maps). In phase 2, 597 SNOMED CT concepts had exact match to 578 distinct ICD-11 Foundation entities (there were some cases of 2 SNOMED CT concepts mapping to the same ICD-11 entity), among which 288 ICD-11 entities were used as source codes to map to SNOMED CT in phase 1. For these 288 ICD-11 entities, 233 (80.9%) were symmetrical with phase 2 maps. Many of the “asymmetrical” maps could be attributed to evolution of the mapping methodology as the project progressed. For example, the ICD-11 Foundation entity Pendred syndrome was mapped to the SNOMED CT concept 70348004 Pendred's syndrome in phase 1. However, in phase 2, the ICD-11 target was rejected after examining the synonyms of the SNOMED CT concept, which included Genetic defect in thyroid hormonogenesis II B and Hypothyroidism with sensorineural deafness, both conditions were considered distinct entities from Pendred syndrome in the ICD-11 Foundation.

Interrater agreement

For both phases, each map was created by 2 mappers independently, compared and discussed if there was discrepancy. In phase 1, excluding the 120 cases which were used to establish the mapping guidelines, the mappers agreed in 412/520 (79.2%) cases. For phase 2, the agreement rate was 1429/1893 (75.5%). The concurrence rate among mappers appears to be similar for mapping in either direction.

Discussion

Benefits of interoperability

Achieving interoperability between SNOMED CT and ICD-11 will provide benefits in the following areas:

Content development, maintenance, and quality assurance—there may be opportunities for cost and time savings from collaborative work in content development and maintenance. Clinical experts will not be required to engage in duplicative activities but can simultaneously provide input to both coding systems. Content alignment or mapping activity often provides valuable insight into problematic areas of content on both sides of the map and highlights opportunities to improve the coverage, accuracy, and usability of each system.

Coded data generation—the translation of coded data from one coding system to another, be it a fully or semi-automated (with human review) process, can enable faster, more accurate and more consistent coding, which can potentially result in coding cost reduction and shorter reimbursement time. In an experimental setting, it has been shown that leveraging a map to generate ICD-10-CM codes based on SNOMED CT-encoded data resulted in shorter coding time and potential improvement in coding reliability and accuracy. An example of this is to use SNOMED CT coded clinical data in the electronic health record to generate ICD-11 codes for reporting and billing.

Coded data usage—the ability to integrate and pool together data encoded in SNOMED CT (typically clinical systems, eg, electronic health records) and ICD (typically administrative systems, eg, insurance claims) will broaden the scope of usable data sources and increase the amount of data that can be re-used for secondary use cases, such as research, data analytics, and population health statistics. A possible scenario is to incorporate ICD-11 coded administrative data into SNOMED CT coded clinical datasets for clinical observational studies. Even though the translation of ICD-11 codes into SNOMED CT may entail some information loss because of granularity differences, the additional data source is likely to provide value.

Lessons learned and recommendations

Recognizing the importance of aligning the 2 coding systems, there has been long-standing collaborative efforts between WHO and SNOMED International, including this pilot mapping project. Through this pilot project, important lessons were learned, which should be carefully considered by both organizations in their future work.

Clarify goals and use cases

The pilot project is focused on finding exact equivalence between SNOMED CT concepts and ICD-11 Foundation entities. Exact matches allow for automatic, “loss-less” translation from one coding system to another. This may be required for use cases such as direct patient care, in which potential change or loss of meaning or detail should be avoided. However, in other use cases (eg, statistical reporting), exact matches are not required. It is appropriate, or even desirable, to aggregate specific codes into more general categories. This is particularly relevant in mapping from SNOMED CT to ICD-11. A specific SNOMED CT concept can be mapped to a broader ICD-11 Foundation entity, which will be rolled up to a stem code in ICD-11 MMS for health statistics reporting. Therefore, it is important to revisit the strict requirement of equivalence because inexact maps can be useful too. It is recommended that the map should accommodate different use cases and that the intended method of employing the map should be defined for each scenario.

Provide adequate resources

The work to create the map and to subsequently maintain it must not be underestimated. Mapping is not an exact science, and it takes in-depth knowledge in both coding systems to understand the nuances due to differences in terming, use of synonyms, hierarchical structure, and organizing principles. It is very time-consuming to discuss and reconcile maps that are different, and the resolution sometimes requires clinical expertise. One finding of the pilot is that the time it takes to resolve differences is twice that for creating the maps. Full commitment from both organizations is essential to provide the necessary resources. The resource requirements generally fall under 3 areas:

Human resources—The pilot project relied on volunteer effort from member countries. Future work cannot be undertaken on volunteer effort alone. It needs a dedicated project team with full-time project managers, mapping experts with in-depth knowledge in both coding systems, and supporting personnel (including input from clinical experts). A steering committee with representation from both organizations is needed to oversee and direct the project, resolve high-level issues (eg, licensing and intellectual property rights), champion the project to leadership and stakeholders, and ensure adequate support and timely action (including sufficient resources to respond to change requests in SNOMED CT and ICD-11).

Tooling—Spreadsheets were used in the pilot project for creating, reviewing and recording the maps. Their use was generally cumbersome, time-consuming, and error prone. Better tools are required that will allow efficient capture, review, and conflict resolution of the maps. They should provide integrated and convenient browsing of the 2 coding systems and facilitate easy communication between team members. The tools should also leverage state-of-the-art techniques (eg, deep learning, artificial intelligence) to generate suggestions to the map specialists. Even though fully automated mapping is still not realistic currently, machine-assisted mapping will likely lead to improved efficiency and consistency.

Mapping guidelines and editorial changes—A set of initial mapping guidelines was developed in the pilot project. What became evident was that the guidelines needed iterative updating as the project progressed. The current mapping guidelines can serve as the starting point for future work, where comprehensive guidelines should be ready at project initiation. A quality assurance plan should be in place to revisit maps to ensure accuracy and consistency in the mappings, especially when guidelines change. This pilot identified some common issues, including non-synonymous synonyms, composite conditions and residual categories. These issues need to be discussed and resolved. Existing content issues within each coding system should be promptly cleaned up. In the pilot, postcoordination was used only in ICD-11 but not in SNOMED CT. Postcoordination is most useful in adding details to an existing entity or concept. Since SNOMED CT concepts are generally finer-grained than ICD-11, whether it is worthwhile to use postcoordination in SNOMED CT remains to be determined.

Set up a road map

A complete map between SNOMED CT and ICD-11 will be a multi-year project. It is important to develop a road map, with well-defined phases and milestones, so that results can be delivered early to, be tested and deployed by users. Instead of wholesale mapping of full chapters and disease areas, an alternative may be to focus on frequently used codes based on the usage statistics of the 2 systems. Initial work may focus on more straightforward conditions, leaving more complex conditions to later. With a phased approach, it is easier to monitor progress, keep stakeholders engaged, and gather feedback.

The pilot may provide some estimation on the time scale for a full map. It took 10 months to create maps between 1900 SNOMED CT concepts and 700 ICD-11 Foundation entities, with a small team of dedicated volunteers who contributed their efforts around their normal duties. A considerable amount of that time was spent on building the pilot project from scratch, which included creating and updating the mapping guidelines, and working out the workflow and logistics. With a full-time team, a set of clear guidelines and the proper tools, mapping could proceed at a considerably faster pace. In addition, resolution of the issues highlighted above (eg, non-synonymous synonyms, composite conditions) would make mapping easier. Nonetheless, since the pilot only covered a small portion of the 2 coding systems, it may be necessary to perform a more extensive study before deciding on a definitive work plan.

Reconsider using SNOMED CT directly in the ICD-11 Foundation

One resounding observation of this pilot project is the tremendous amount of effort required to create (and subsequently maintain) an equivalence map between 2 coding systems that are evolving independently. Even if that could be achieved, one would question the value of having 2 identical coding systems. If the ultimate goal is to maximize interoperability between SNOMED CT and ICD-11, the direct use of SNOMED CT as an ontology to build the ICD-11 Foundation is a better solution than a map. This would obviate the need to create post hoc mappings, which are expensive to build and an approximation of equivalence at best. We are aware that WHO is currently considering to incorporate terminologies such as the Human Phenotype Ontology, Mondo Disease Ontology, and RadLex Radiology Lexicon into the ICD-11 Foundation. It is recommended that WHO and SNOMED International should seriously reconsider their original aspiration to include SNOMED CT as part of the ICD-11 Foundation. The best time to start this work is now, since ICD-11 is already officially released, which takes away the time pressure on the WHO side. Further delay is likely to result in more divergence between the 2 systems, making future adaptation more difficult. Before adopting SNOMED CT as part of the ICD-11 Foundation ontology, some form of mapping to assess the degree of congruence between the ICD-11 Foundation and SNOMED CT will be necessary to identify content gaps and other issues. The findings and lessons learned from this pilot project will benefit the planning and execution of such work in future.

Limitations of this work

This pilot project was based on a relatively small sample from the 2 coding systems, which may not be representative of the overall content. It may also be insufficient to fully gauge the effort required for a comprehensive map. Moreover, as the mapping guidelines needed to be modified as the mapping was progressing, earlier maps may not be fully compliant with the guidelines. A more extensive feasibility study based on the findings of this pilot may be necessary to further refine mapping rules, processes, and other essential aspects of mapping.

Conclusion

The pilot project to map between the endocrine disease content of SNOMED CT and ICD-11 Foundation resulted in exact maps for 59% of the ICD-11 Foundation entities and 46% of the SNOMED CT concepts. Common problems encountered in mapping included: non-synonymous synonyms, mismatch in granularity, composite conditions, and residual categories. Resolving these problems would likely increase the exact mapping rate considerably. Future collaborative work between SNOMED International and WHO will benefit from the findings of this pilot study. It is recommended that the 2 organizations should clarify goals and use cases of the map, provide adequate resources, set up a road map, and reconsider their original proposal of incorporating SNOMED CT into the ICD-11 Foundation ontology.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jane Millar and Donna Morgan of SNOMED International for their leadership and support of the pilot project, and their suggestions for the manuscript. We thank Eva Krpelanova of the World Health Organization, and Frank Geier of the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices of Germany for their support of the pilot project. A special thanks to Betsy Humphreys for her suggestions for the manuscript.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. WHO’s new International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) comes into effect. Accessed June 6, 2024. https://www.who.int/news/item/11-02-2022-who-s-new-international-classification-of-diseases-(icd-11)-comes-into-effect

- 2. World Health Organization. ICD–11 fact sheet. Accessed June 6, 2024. https://icd.who.int/en/docs/icd11factsheet_en.pdf

- 3. Doctor H, Rashidian A, Hajjeh R, et al Improving health and mortality data in Eastern Mediterranean Region countries: implementation of the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11). East Mediterr Health J. 2021;27(2):111–112.

- 4. Ibrahim I, et al ICD-11 morbidity pilot in Kuwait: methodology and lessons learned for future implementation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(5):3057.

- 5. World Health Organization. WHO nomenclature regulations 1967. Accessed June 6, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/who-nomenclature-regulations-1967

- 6. SNOMED International. What is SNOMED CT? Accessed June 6, 2024. https://www.snomed.org/five-step-briefing

- 7. SNOMED International. Standards partner: World Health Organization. Accessed June 6, 2024. https://www.snomed.org/standards-partnerships/world-health-organization

- 8. SNOMED International. SNOMED CT maps: ICD-10. Accessed June 6, 2024. https://www.snomed.org/maps#:∼:text=SNOMED%20CT%20to%20ICD%2D10,in%20registries%20and%20diagnosis%20groupers

- 9. Fung KW, Xu J, Bodenreider O. The new International Classification of Diseases 11th edition: a comparative analysis with ICD-10 and ICD-10-CM. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(5):738–746.

- 10. Harrison JE, Weber S, Jakob R, et al ICD-11: an international classification of diseases for the twenty-first century. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2021;21(Suppl 6):206.

- 11. Chute CG, Celik C. Overview of ICD-11 architecture and structure. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2022;21(Suppl 6):378.

- 12. Mamou M, Rector A, Schulz S, et al ICD-11 (JLMMS) and SCT inter-operation. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2016;223:267–272.

- 13. Mamou M, Rector A, Schulz S, et al Representing ICD-11 JLMMS using IHTSDO representation formalisms. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2016;228:431–435.

- 14. Rodrigues J-M, Robinson D, Della Mea V, et al Semantic alignment between ICD-11 and SNOMED CT. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;216:790–794.

- 15. Rodrigues JM, Schulz S, Mizen B, et al Scrutinizing SNOMED CT's ability to reconcile clinical language ambiguities with an ontology representation. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2018;247:910–914.

- 16. Rodrigues J-M, Schulz S, Rector A, et al ICD-11 and SNOMED CT common ontology: circulatory system. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2014;205:1043–1047.

- 17. SNOMED International. Position statement: SNOMED CT to ICD-11-MMS map. Accessed June 6, 2024. https://www.snomed.org/news/position-statement%3A-snomed-ct-to-icd-11-mms-map

- 18. World Health Organization. WHO-FIC classifications and terminology mapping: principles and best practice. Accessed June 6, 2024. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/classification/who-fic-network/whofic_terminology_mapping_guide.pdf?sfvrsn=2cae387c_7&download=true

- 19. International Organization for Standardization (ISO). ISO/TR 12300:2014 health informatics—principles of mapping between terminological systems. Accessed June 6, 2024. https://www.iso.org/standard/51344.html

- 20. SNOMED International. SNOMED CT browser. Accessed June 6, 2024. https://browser.ihtsdotools.org/?

- 21. World Health Organization. ICD-11 foundation component browser. Accessed June 6, 2024. https://icd.who.int/dev11/f/en#/

- 22. World Health Organization. ICD-11 coding tool. Accessed June 6, 2024. https://icd.who.int/devct11/icd11_mms/en/beta

- 23. Mendonca EA, et al Reproducibility of interpreting “and” and “or” in terminology systems. In: Proceedings of the AMIA Symposium 1998: 790–794.

- 24. Fung KW, et al Using SNOMED CT-encoded problems to improve ICD-10-CM coding-A randomized controlled experiment. Int J Med Inform. 2019;126:19–25.