Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, studies have reported that children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) experience greater overall perceived stress compared to children without ADHD (), and that the experience of stress during childhood and adolescence can have a prolonged influence on future ADHD symptom severity (; ). Children with ADHD may be more sensitive to the effects of stress compared to their peers without neurodevelopmental conditions (). Experiencing multiple stressors over time may have an additive effect on ADHD symptom severity and other mental health symptoms (). For example, exposure to stressors in childhood such as illness, conflict, and school pressure have been associated with increased ADHD symptom severity in adolescence (). High levels of stress exposure have also been prospectively associated with persistent ADHD symptoms and emotion dysregulation from childhood into young adulthood ().

The COVID-19 pandemic is a recent and chronic global health emergency and stressor that may be impacting negatively on the adjustment of children with ADHD. The first COVID-19 case in Australia was recorded in January 2020 and led to a nationwide lockdown from March to May 2020 (). As was the case in many countries, this lockdown resulted in adults working from home, children participating in remote learning, and reliance on the internet for social interactions and connecting with friends and family (). Ongoing lockdowns, social distancing measures, and travel restrictions were present throughout Australia, with the State of Victoria entering a second strict lockdown in July to October 2020, which comprised of a night-time curfew, a 5-km (3.1 mile) travel radius, and limited reasons to leave home. Other parts of Australia experienced multiple, rapidly enforced lockdowns (e.g., 3 days to 2 weeks) to contain the virus. For example, the State of Victoria entered a fourth lockdown in May 2021 for 2 weeks and a fifth in July 2021 for 12 days due to several new cases (24–26) identified in the community ().

The pandemic has been a major life stressor in Australia and internationally, including fear of contracting the COVID-19 virus, as well as stress potentially arising from government enforced social distancing restrictions, significant lifestyle constraints, and changes to social connections with family and friends. Pandemic-related stressors such as these have led to a 25% increase in anxiety and depression worldwide, according to a report by the . An Australian survey found that 38% of adults had experienced at least one COVID-19 related stressor in October 2020 and that 23% were still experiencing COVID-19 related stress in April 2021 despite some relaxation of restrictions ().

The uncertainties and changes that have arisen as a result of the pandemic have also been stressful for many children, and this stress may be acted out through increased challenging behaviors () or anxiety (). Increased rates of mental health problems in children during the pandemic have also been reported, with one meta-analysis finding that 70% to 90% of children experienced a decline in mental health during lockdown (). More specifically, studies have found elevated child stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms (), irritability and inattention (; ), hyperactivity (), and oppositional symptoms (). Additionally, one study found associations between child stress during lockdown, and elevated irritability, inattention, and hyperactivity (). Given that children with ADHD may be particularly impacted by stress, understanding the consequences that COVID-19 induced stress may have had on ADHD symptoms and broader mental health symptoms is essential.

Studies specifically focusing on children with ADHD during the pandemic have reported increased ADHD symptoms (), irritability (), and oppositional symptoms (). Further, elevated ADHD symptom severity during the pandemic has been associated with home-learning difficulties (; ), boredom (; ; ), and trauma reactions to lockdown, mediated by irritability (). Increased symptoms of anxiety () and depression () in children with ADHD have also been evident in the early stages of the pandemic. However, the role of stress in understanding the observed increase in ADHD symptom severity and mental health symptoms during the pandemic has been limited.

A cross-sectional study by investigated the impacts of the pandemic in a sample of 213 children aged 5 to 17 years with ADHD using parent report. The study found that approximately one-third of children with ADHD experienced moderate to extreme COVID-19 stress in the early stages of the pandemic, which was independently associated with poorer mental health outcomes including worry, sadness, anxiety, fatigue, loneliness, irritability, distractibility, and fidgeting, and occurred irrespective of ADHD medication use and pre-existing co-occurring internalizing and externalizing conditions (). However, the cross-sectional design limits capacity to understand whether COVID-19 stress predicts symptom severity, and less is known about the longitudinal relationships between stress, ADHD symptoms, and mental health symptoms as the pandemic continues. Additionally, mental health symptoms were assessed using single items, rather than a more comprehensive measure of each mental health domain. For example, single items assessed distractibility and fidgeting rather than a validated ADHD rating scale.

The current study examined the same cohort with longitudinal data to investigate whether COVID-19 stress experienced in the early stages of the pandemic was prospectively associated with ADHD symptom severity, oppositional symptoms, and domains of mental health including negative affect, anxiety, depression, and irritability 12-months later. It was hypothesized that increased levels of COVID-19 stress at baseline would be associated with greater frequency and severity of ADHD, oppositional, and mental health symptoms 12-months later, after accounting for child age, gender, ADHD medication use, neighborhood socio-economic status, and baseline symptoms.

Method

Study Design

This study used two waves of data (baseline and 12-month follow-up) from the ADHD COVID-19 study, which is a longitudinal study surveying parents of Australian children with ADHD during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study was approved by the Deakin University Health Faculty Ethics Committee (HEAG-H 60_2020).

Participants and Procedure

Participants were recruited in May 2020 through ADHD organizations, social media, and ADHD parent support groups. Parents and primary caregivers (>18 years old) living in Australia with a child aged 5 to 17 years who had been diagnosed with ADHD were eligible to participate. Of 221 participants recruited at baseline, 207 remained in the study and were invited by email to take part in a 12-month follow-up survey in May 2021. The survey was completed online through Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap; , ). The 12-month follow-up survey was open for 8 weeks. Weekly reminders for the 12-month follow-up were sent to participants using a range of communication methods including email, text message, and two phone call attempts, with a final reminder email sent 1 week before the survey closed. Participants were given a $20 e-voucher after completing the 12-month survey to thank them for their time.

Materials and Measures

Child COVID-19 Stress

The CoRonavIruS Health and Impact Survey (CRISIS; ) measures the impact of pandemic-induced life changes on mental health. The following four items from the Life Changes domain of the CRISIS were used to create a COVID-19 stress measure in the baseline survey for parent-report: (1) How stressful have the restrictions on leaving home been for your child? (2) How stressful have these changes in family contacts been for your child? (3) How stressful have these changes in social contacts been for your child? (4) How much has cancellation of important events in your child’s life been difficult for him/her? Items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all to 5 = very extremely), where higher scores indicated greater stress. The Life Changes domain of the CRISIS has demonstrated good internal reliability (ω = .73–.77) and high consistency between US and UK samples (r = .91–.99) using parent report (). The COVID-19 stress measure developed specifically in this study has also been validated through a confirmatory model (). Cronbach’s alpha for the sample used in the current study showed an acceptable level of internal reliability for the COVID-19 stress measure, α = .79.

ADHD Symptom Severity and Oppositional Symptoms

ADHD and oppositional symptoms were measured at baseline and 12 months using the 26 item Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham Rating Scale—Fourth Version (SNAP-IV; ). Parents reported on their child’s inattention (nine items), hyperactivity/impulsivity (nine items), and oppositional symptoms (eight items) on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = not at all to 3 = very much), with higher scores indicating increased symptom severity. The inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity subscales were also combined to provide an ADHD symptom severity total score. The SNAP-IV has previously demonstrated excellent internal reliability for parent ratings (α = .94; ), and in the current sample, was excellent for ADHD symptom severity (α = .91) and inattention symptoms (α = .90), and very good for hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms (α = .88) and oppositional symptoms (α = .89) at the 12 month time point.

Mental Health

Negative Affect

Ten items from the Mood States domain of the CRISIS were used at baseline and 12 months for parents to report their child’s mood from the circumplex model of affect, including worry, happy versus sad, enjoying usual activities, anxiety, fatigue, irritability, fidgety or restless, difficulty to concentrate or focus, loneliness, and negative thoughts. Scores were measured on a 5-point Likert Scale for each mood state (1 = not at all to 5 = extremely) except for happy versus sad and enjoying activities, which were reverse scored. A total score was calculated, with higher scores indicating more negative mood states. Cronbach’s alpha showed very good internal reliability within the sample at 12 months, α = .82.

Depression

Parents reported on their child’s depressive symptoms using the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ) at baseline and 12 months. The SMFQ is a reliable 13-item measure (α = .85–.87; ) assessing depressive symptoms using a 3-point Likert Scale (0 = not true to 2 = true). Higher scores indicated greater symptoms of depression. The SMFQ showed excellent internal reliability within the sample at 12 months, α = .90.

Anxiety

The brief version of the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS; ) was used to assess parent-reported anxiety at baseline and 12 months. The brief 8-item version () measures anxiety on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = never to 3 = always), with higher scores indicating greater symptoms of anxiety. The original SCAS has shown excellent reliability (α = .92; ) and has been validated for use by parents of children aged 6 to 18 years (α = .89; ). Cronbach’s alpha showed a very good level of internal reliability within the sample at 12 months, α = .85.

Irritability

The Affective Reactivity Index (ARI) was used at baseline and 12 months to measure parent-reported chronic irritability symptoms on seven items using a 3-point Likert Scale (0 = not true to 2 = certainly true). Higher scores indicated greater irritability. The ARI has been validated for parent-report in a clinical sample longitudinally, including a percentage of children with ADHD (α = .89–.92; ). The ARI demonstrated excellent internal reliability within the sample at 12 months, α = .91.

Demographics

In the baseline survey, parents reported their country of birth, Australian state of residence (by postcode), primary language spoken at home, Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander status, high school completion, number of children in the home, child age, and child gender. Information regarding the child’s ADHD medication use, and diagnosis or treatment of any co-occurring internalizing (anxiety and depression) or externalizing (oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder) conditions were assessed at baseline and the 12-month follow-up. The Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA; ) was calculated as a general socio-economic indicator based on participants’ postcode at baseline.

Statistical Analyses

To be included in the analyses, participants were required to have data available on COVID-19 stress at baseline, and at least one outcome of interest at the 12-month follow-up. Independent samples t-tests and chi-square tests for independence examined any differences in child age, neighborhood socio-economic status, child gender, and state of residence between those included and excluded from the analyses. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic and individual characteristics of the sample, as well as the range and average responses for the outcomes of interest.

Linear regression analyses examined the associations between baseline COVID-19 stress (independent variable) and 12-month ADHD symptom severity (including inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity subscales), oppositional symptoms, negative affect, anxiety, depression, and irritability (dependent variables) at 12 months. Two sets of adjusted analyses for each domain were also undertaken. First, adjusted linear regression analyses were conducted to account for covariates—ADHD medication use, child age, gender, and neighborhood socio-economic status. Second, adjusted analyses were re-run to account for baseline symptoms of the dependent variable of interest and covariates. Due to the number of statistical comparisons, a False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction was used for both sets of adjusted analyses using q = 0.0125 as the threshold for significance (). IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 28) was used to complete all data analyses.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Seventy percent of invited participants completed the 12-month survey (see Supplemental Figure 1); with 140 responses eligible for analysis. There was no significant difference between the age of children included in the analyses (n = 140, M = 10.59 years, SD = 3.00) and excluded (n = 65, M = 10.62 years, SD = 3.20), t(203) = 0.05, p = .961, 95% confidence interval (CI) [−0.89, 0.93], or neighborhood socio-economic status between those included (n = 136, M = 1,040.85, SD = 52.36) and excluded (n = 67, M = 1,033.25, SD = 46.89), t(201) = −1.01, p = .316, 95% CI [−22.49, 7.31]. There was no significant effect of gender distribution χ2 (df = 1, n = 204) = 0.14, p = .706, = −0.03, or state of residence χ2 (df = 6, n = 207) = 5.47, p = .485, = 0.16, between those included and excluded.

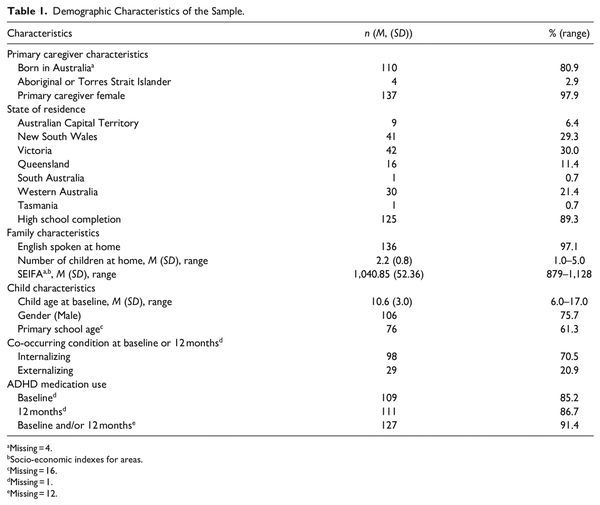

As shown in Table 1, the average age of the sample at baseline was 10.6 years and most children were male. Co-occurring internalizing conditions were more prevalent than externalizing conditions. There were very similar rates of ADHD medication use at baseline (85%) and 12 months (87%). Most parents were female and had completed high school. Approximately 60% of the sample lived in New South Wales or Victoria. The average scores for each outcome of interest remained similar across the two time points (see Supplemental Table 1).

Longitudinal Associations Between COVID-19 Stress and Outcomes at 12 Months

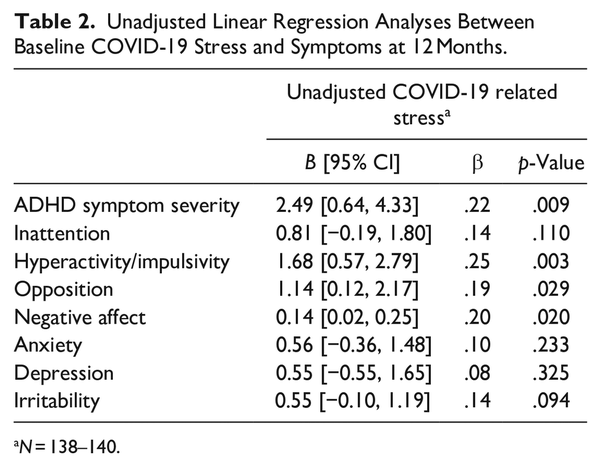

Bivariate correlations between the variables of interest can be found in Supplemental Table 2. In the unadjusted models, baseline COVID-19 stress was significantly associated with increased 12-month ADHD symptom severity (β = .22, p = .009), and more specifically, increased hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms (β = .25, p = .003; see Table 2). COVID-19 stress was also significantly associated with increased oppositional symptoms (β = .19, p = .029), and negative affect (β = .20, p = .020) at 12 months (see Table 2). There was no significant association between COVID-19 stress and inattention symptoms, anxiety, depression, or irritability.

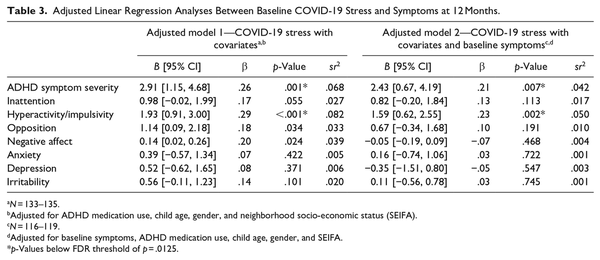

When adjusting for covariates, baseline COVID-19 stress remained significantly associated with increased ADHD symptom severity (β = .26, p = .001) and hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms (β = .29, p < .001) at 12 months. While associations were also shown between COVID-19 stress and increased oppositional symptoms (β = .18, p = .034), and negative affect (β = .20, p = .024), these findings did not survive FDR correction (see Table 3). When adjusting for covariates and baseline symptoms, baseline COVID-19 stress remained associated with increased ADHD symptom severity (β = .21, p = .007) and hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms (β = .23, p = .002) at 12 months (see Table 3). Both associations survived FDR correction. An expanded version of this table including baseline symptoms and covariates is presented in Supplemental Table 3.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the longitudinal associations between children’s COVID-19 stress and ADHD symptom severity, oppositional symptoms, negative affect, anxiety, depression, and irritability in Australian children aged 5 to 17 years with ADHD at two-time points during the pandemic. The hypothesis was partially supported, as COVID-19 stress reported in the early months of the pandemic was significantly associated with greater ADHD symptom severity, hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms, oppositional symptoms, and increased negative affect 12 months later after accounting for covariates. COVID-19 stress also continued to be associated with greater ADHD symptom severity, specifically hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms when accounting for baseline symptoms.

The significant association shown between baseline COVID-19 stress and 12-month ADHD symptom severity is consistent with pre-pandemic research indicating associations between stress and exacerbated ADHD symptom severity across time in childhood and adolescence (; ). The results also support the cross-sectional associations in the early months of the pandemic between COVID-19 stress and symptoms of ADHD such as fidgeting (). The current study expands these findings by indicating ongoing associations between COVID-19 stress and ADHD symptom severity over 12 months, independent of the influence of demographic variables, medication use, and baseline symptoms in the early months of the pandemic.

However, there were differences between specific ADHD symptoms. While baseline COVID-19 stress was associated with symptoms of hyperactivity/impulsivity at 12 months, there was no significant association with inattention symptoms, despite previous research indicating a deterioration in focus and attention in children with ADHD during the early stages of the pandemic (; ; ). These findings support claims made by that pandemic-related stress in children may be more likely to manifest as externalizing symptoms. During stay-at-home restrictions, children have spent more time indoors and had less opportunity to socialize with friends. Additionally, children with ADHD have experienced increased feelings of boredom (; ; ), restlessness, and lack of interest in activities () during the pandemic. As boredom has been linked to distress () and ADHD symptom severity (), it is possible that externalizing symptoms may be more susceptible to stress than other mental health symptoms. This may explain the associations shown between COVID-19 stress and hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms and to an extent, oppositional symptoms. However, the association between baseline COVID-19 stress and 12-month oppositional symptoms should be interpreted with caution as this association did not survive FDR correction when accounting for covariates. Supports that are targeted and specific to addressing the symptoms most strongly impacted by stress could be beneficial to improve outcomes for children with ADHD and their families as the pandemic continues.

There was also some evidence of a prospective association between COVID-19 stress in the early months of the pandemic and greater negative affect 12 months later, albeit not in other domains of mental health such as anxiety and depression. Again, however, this association did not hold after FDR correction for multiple comparisons, so should be interpreted with caution and requires further research. These findings were unexpected given the associations identified between stress and aspects of mental health such as anxiety, depression, and irritability for children with ADHD prior to (; ), and during (; ), the pandemic. One explanation for the non-significant associations in the current study may be the reported benefits for children with ADHD in the early stages of the pandemic such as consistent routine () or more time spent with family (). Such benefits have been associated with decreased mental health symptoms during the pandemic ().

There are several clinical implications stemming from this study. For clinicians working with children with ADHD, it is important to enquire about, and acknowledge, the various causes of stress relating to the pandemic and the impacts this may have on children’s symptoms. While general clinical guidance has suggested that children with ADHD should continue to be supported in accessing and monitoring medication use during the pandemic (), they may also require additional assistance to foster effective and positive coping strategies during the pandemic (). For example, one study found that consistent routine is especially important for children with ADHD to reduce stress during the pandemic (). In the early stages of the pandemic, many children with ADHD were spending less time outdoors and participating in physical activity, and more time gaming or using social media (; ). These factors could also be considered by parents and clinicians when addressing stress in children with ADHD. Other considerations may include diet and sleep (). Parents may require support to manage their own stress to be able to help their children cope during the pandemic and address any adverse impacts on ADHD symptoms, particularly hyperactivity/impulsivity. A family systems approach may be helpful to improve coping strategies and mental health (; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2021). This approach is appropriate to be delivered via telehealth to support families of children with ADHD in the case of isolation or other social distancing restrictions ().

The results of this study should be interpreted in the context of some limitations. First, we only examined baseline levels of COVID-19 stress. It is unknown how COVID-19 stress changed over the 12-month period given that many parts of Australia experienced additional lockdowns and restrictions after the baseline survey. Furthermore, parent reports may be influenced by their own stress and worries due to the pandemic. Future research should consider gaining children’s perspectives during the pandemic to assess any discrepancies between parent and child reports. Moreover, no control group was used in the study, so it is unknown whether these results are specific to children with ADHD. However, based on previous findings (), it is likely that the associations shown in the study would be more pronounced in children with ADHD compared to their non-ADHD peers. It should also be noted that co-occurring internalizing conditions were higher in the sample than expected.

The study also had multiple strengths. First, the retention of participants was relatively high across the 12 months. Second, the study controlled for additional factors such as ADHD medication use, socio-economic indicators, and baseline symptoms. This allowed the impact of COVID-19 stress to be assessed independently from other factors known to influence ADHD, oppositional, and mental health symptoms. This addressed a common limitation of previous studies focusing on ADHD during the pandemic (; ; ).

Since the 12-month survey, multiple parts of Australia have experienced additional lockdowns and a return to remote learning. New South Wales and Victoria experienced a rise in case numbers in July and August 2021, prompting extended lockdowns in these states. During this time, Melbourne, Victoria became the most locked-down city in the world (). The number of cases of COVID-19 in Australian children has also risen compared to 2020 (), which may contribute to increased COVID-19 stress in children. Future research could also expand upon the current study by considering any differences in COVID-19 stress for primary-school aged children versus high school students, or between states of Australia. Given the small but significant association identified between COVID-19 stress and ADHD symptoms, it is important for research to continue to monitor any longer-term outcomes.

In conclusion, baseline COVID-19 stress was associated with increased ADHD symptom severity 12 months later, specifically hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms, in children aged 5 to 17 years with ADHD. These long-term associations were independent of baseline symptoms and other demographic factors, co-occurring conditions, and ADHD medication use. Children with ADHD and their families may require additional support to cope with ongoing COVID-19 stress as the pandemic continues. Future research should continue to investigate the longer-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the influence of stress on the mental health of children with ADHD over time.

We would like to thank all the participants for their time and invaluable contributions to this project. Thank you to the ADHD support groups and organizations that facilitated recruitment for this study.

Author Contributions Ms Summerton conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, conducted data analyses, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Ms Bellows contributed to the study design, project coordination, data acquisition, and critically reviewed the manuscript. A/Prof Sciberras contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study, project coordination, data analysis and interpretation, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. A/Prof Westrupp, A/Prof Stokes, Prof Coghill, Prof Bellgrove, A/Prof Hutchinson, A/Prof Becker, A/Prof Melvin, Dr Quach, A/Prof Efron, Prof Stringaris, Prof Middeldorp, and Prof Banaschewski contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: A/Prof Sciberras receives royalties from her book published through Elsevier: Sleep and ADHD: An Evidence-Based Guide to Assessment and Treatment. Prof Coghill has received honoraria from Medice, Novartis, Servier, and Takeda, and royalties from Oxford University Press and Cambridge University Press. A/Prof Becker has received grant funding from the Institute of Education Sciences (IES), U.S. Department of Education; National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH); and Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation (CCRF) and has received book honoraria from Guilford Press. A/Prof Sciberras, Prof Coghill, and Prof Middeldorp are on the board of the Australian ADHD Professionals Association (AADPA). Prof Bellgrove is President of AADPA, which is leading the development of National Clinical Guidelines for ADHD in Australia. Prof Banaschewski served in an advisory or consultancy role for eye level, Infectopharm, Lundbeck, Medice, Neurim Pharmaceuticals, Oberberg GmbH, Roche, and Takeda. He received conference support or speaker’s fee by Janssen, Medice, and Takeda. He received royalties from Hogrefe, Kohlhammer, CIP Medien, Oxford University Press; the present work is unrelated to these relationships.

Funding The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding support for this project was provided through the Centre for Social and Early Emotional Development, a Strategic Research Centre of the Office of the Deputy Vice Chancellor Research, Deakin University Australia. A/Prof Sciberras is currently supported by an Australian Medical Research Future Fund Investigator Grant (#1194297) and was previously funded by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Career Development Fellowship (1110688) and a veski Inspiring Women’s Fellowship. A/Prof Quach receives funding from the AXA Research Impact Fund. A/Prof Efron was supported by a Clinician Scientist Fellowship from the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute (MCRI). A/Prof Hutchinson was supported by a NHMRC Investigator Grant (1197488). MCRI is supported by the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support program.

Ainsley Summerton

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6732-5294

Stephen P. Becker

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9046-5183

Emma Sciberras

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2812-303X

Supplemental Material Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Angold A., Costello E.J., Messer S.C., Pickles A., Winder F., Silver D. (1995). The development of a questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 5(4), 237–249.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2018). Socio-economic indexes for areas. https://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/seifa

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2021). Household impacts of COVID-19 survey. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/household-impacts-covid-19-survey/apr-2021

- Becker S. P., Breaux R., Cusick C. N., Dvorsky M. R., Marsh N. P., Sciberras E., Langberg J. M. (2020). Remote learning during COVID-19: Examining school practices, service continuation, and difficulties for adolescents with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(6), 769–777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.09.002

- Behrmann J. T., Blaabjerg J., Jordansen J., Jensen de, López K. M. (2022). Systematic review: Investigating the impact of COVID-19 on mental health outcomes of individuals with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 26(7), 959–975. https://doi.org/10.1177/10870547211050945

- Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 57(1), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.2307/2346101

- Boaz J. (2021, ). Melbourne passes Buenos Aires’ world record for time spent in COVID-19 lockdown. ABC. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-10-03/melbourne-longest-lockdown/100510710

- Breaux R., Dvorsky M. R., Marsh N. P., Green C. D., Cash A. R., Shroff D. M., Buchen N., Langberg J. M., Becker S. P. (2021). Prospective impact of COVID-19 on mental health functioning in adolescents with and without ADHD: Protective role of emotion regulation abilities. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 62(9), 1132–1139. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13382

- Bussing R., Fernandez M., Harwood M., Wei H., Garvan C. W., Eyberg S. M., Swanson J. M. (2008). Parent and teacher SNAP-IV ratings of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms: Psychometric properties and normative ratings from a school district sample. Assessment, 15(3), 317–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191107313888

- Cockburn P. (2021, ). Children and teens account for one third of COVID-19 cases in NSW. ABC. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-08-12/nsw-covid-cases-in-those-under-19/100371666

- Cortese S., Asherson P., Sonuga-Barke E., Banaschewski T., Brandeis D., Buitelaar J., Coghill D., Daley D., Danckaerts M., Dittmann R. W., Doepfner M., Ferrin M., Hollis C., Holtmann M., Konofal E., Lecendreux M., Santosh P., Rothenberger A., Soutullo C., . . . European A. G. G. (2020). ADHD management during the COVID-19 pandemic: Guidance from the European ADHD Guidelines Group. Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(6), 412–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30110-3

- Cost K. T., Crosbie J., Anagnostou E., Birken C. S., Charach A., Monga S., Kelley E., Nicolson R., Maguire J. L., Burton C. L., Schachar R. J., Arnold P. D., Korczak D. J. (2022). Mostly worse, occasionally better: Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian children and adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31, 671–684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01744-3

- Department of Health. (2020). First confirmed case of novel coronavirus in Australia. https://www.health.gov.au/ministers/the-hon-greg-hunt-mp/media/first-confirmed-case-of-novel-coronavirus-in-australia

- Dvorsky M., Breaux R., Cusick C., Fredrick J., Green C., Steinberg A., Langberg J. M., Sciberras E., Becker S. P. (2022). Coping with COVID-19: Longitudinal impact of the pandemic on adjustment and links with coping for adolescents with and without ADHD. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 50, 605–619. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-021-00857-2

- Employment, Labour and Social Affairs Policy Briefs, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2021). Looking beyond COVID-19: Strengthening family support services across the OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/86738ab2-en

- Frick M. A., Meyer J., Isaksson J. (2022). The role of comorbid symptoms in perceived stress and sleep problems in adolescent ADHD. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-022-01320-z

- Harris P. A., Taylor R., Minor B. L., Elliott V., Fernandez M., O’Neal L., McLeod L., Delacqua G., Delacqua F., Kirby J., Duda S. N. REDCap Consortium. (2019). The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software partners. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 95, 103208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

- Harris P. A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap): A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

- Hartman C. A., Rommelse N., van der Klugt C. L., Wanders R. B. K., Timmerman M. E. (2019). Stress exposure and the course of ADHD from childhood to young adulthood: Comorbid severe emotion dysregulation or mood and anxiety problems. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(11), 1824. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8111824

- Humphreys K. L., Watts E. L., Dennis E. L., King L. S., Thompson P. M., Gotlib I. H. (2019). Stressful life events, ADHD symptoms, and brain structure in early adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47(3), 421–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-018-0443-5

- Imran N., Zeshan M., Pervaiz Z. (2020). Mental health considerations for children & adolescents in COVID-19 pandemic. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 36, S1–S6. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2759

- McKee G. B., Pierce B. S., Tyler C. M., Perrin P. B., Elliott T. R. (2022). The COVID-19 pandemic’s influence on family systems therapists’ provision of teletherapy. Family Process, 61(1) 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12665

- Melegari M. G., Giallonardo M., Sacco R., Marcucci L., Orecchio S., Bruni O. (2021). Identifying the impact of the confinement of COVID-19 on emotional-mood and behavioural dimensions in children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Psychiatry Research, 296, 113692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113692

- Nauta M. H., Scholing A., Rapee R. M., Abbott M., Spence S. H., Waters A (2004). A parent-report measure of children’s anxiety: Psychometric properties and comparison with child-report in a clinic and normal sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42(7), 813–839. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00200-6

- Nikolaidis A., Paksarian D., Alexander L., Derosa J., Dunn J., Nielson D. M., Droney I., Kang M., Douka I., Bromet E., Milham M., Stringaris A., Merikangas K. R. (2021). The Coronavirus Health and Impact Survey (CRISIS) reveals reproducible correlates of pandemic-related mood states across the Atlantic. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 8139. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87270-3

- Panda P. K., Gupta J., Chowdhury S. R., Kumar R., Meena A. K., Madaan P., Sharawat I. K., Gulati S. (2021). Psychological and behavioral impact of lockdown and quarantine measures for COVID-19 pandemic on children, adolescents and caregivers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, 67(1), fmaa122. https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/fmaa122

- Rydell A. M. (2010). Family factors and children's disruptive behaviour: An investigation of links between demographic characteristics, negative life events and symptoms of ODD and ADHD. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45(2), 233–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0060-2

- Saline S. (2021). Thriving in the new normal: How COVID-19 has affected alternative learners and their families and implementing effective, creative therapeutic interventions. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 91(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/00377317.2020.1867699

- Sciberras E., Patel P., Stokes M. A., Coghill D., Middeldorp C. M., Bellgrove M. A., Becker S. P., Efron D., Stringaris A., Faraone S. V., Bellows S. T., Quach J., Hutchinson D., Silk T. J., Melvin G., Wood A. G., Jackson A., . . . Westrupp E. (2022). Physical health, media use, and mental health in children and adolescents with ADHD during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Journal of Attention Disorders, 26(4), 549–562. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054720978549

- Shah R., Raju V. V., Sharma A., Grover S. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on children with ADHD and their families: An online survey and a continuity care model. Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice, 12(1), 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1718645

- Sibley M. H., Ortiz M., Gaias L. M., Reyes R., Joshi M., Alexander D., Graziano P. (2021). Top problems of adolescents and young adults with ADHD during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 136, 190–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.02.009

- Spence S. H. (1997). Structure of anxiety symptoms among children: A confirmatory factor-analytic study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106(2), 280–297. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.280

- Spence S. H., Barrett P. M., Turner C. M. (2003). Psychometric properties of the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale with young adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 17(6), 605–625. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0887-6185(02)00236-0

- Spence S. H., Sawyer M. G., Sheffield J., Patton G., Bond L., Graetz B., Kay D. (2014). Does the absence of a supportive family environment influence the outcome of a universal intervention for the prevention of depression? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(5), 5113–5132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110505113

- State Government of Victoria. (2021). CovidSafe settings. https://www.coronavirus.vic.gov.au/coronavirus-covidsafe-settings

- Stringaris A, Goodman R, Ferdinando S, Razdan V, Muhrer E, Leibenluft E, Brotman M. A. (2012). The Affective Reactivity Index: A concise irritability scale for clinical and research settings. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(11) 1109–1117. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02561.x

- Swanson J. M., Kraemer H. C., Hinshaw S. P., Arnold L. E., Conners C. K., Abikoff H. B., Clevenger W., Davies M., Elliott G. R., Greenhill L. L., Hechtman L., Hoza B., Jensen P. S., March J. S., Newcorn J. H., Owens E. B., Pelham W. E., Schiller E., Severe J. B., . . . Wu M. (2001). Clinical relevance of the primary findings of the MTA: Success rates based on severity of ADHD and ODD symptoms at the end of treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(2), 168–179. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200102000-00011

- Uçar H. N., Çetin F. H., Türkoğlu S., Sağliyan G. A., Zekey O. C., Yılmaz C. (2022). Trauma reactions in children with ADHD during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating effect of irritability. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 27(3) 197–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2021.1926782

- World Health Organization. (2022, ). COVID-19 pandemic triggers 25% increase in prevalence of anxiety and depression worldwide. https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide

- Zhang J., Shuai L., Yu H., Wang Z., Qiu M., Lu L., Cao X., Xia W., Yu H., Wang Y., Chen R. (2020). Acute stress, behavioural symptoms and mood states among school-age children with attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder during the COVID-19 outbreak. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 102077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102077