ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder purported to emerge in childhood (). An estimated 11% of children in the United States are diagnosed with ADHD, the majority of whom are male (). However, in adulthood, nearly equivalent numbers of men and women are diagnosed with ADHD (; ), suggesting that opportunities to identify ADHD in childhood may be disproportionately missed for girls and women. Failure to accurately diagnose and treat ADHD earlier in development may have profound consequences, potentially contributing to lower self-esteem and relationship difficulties, limiting income potential, and increasing risk for psychiatric comorbidity and early mortality (; ). However, very little research has examined how women with ADHD eventually obtain a diagnosis of ADHD in adulthood, limiting opportunities for providers to improve clinical care for this underserved population.

Urgency to understand the diagnostic process for women with ADHD is of utmost importance, in light of a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) documenting a marked increase in the prescription of stimulant medication in the United States from 2020 to 2021, particularly for adult women ages 35 years and older (). Although these data reflect prescription of stimulant medication, and do not specifically address the diagnosis of ADHD, these data may signal a changing trend toward addressing the needs of women with ADHD, who have long been overlooked in clinical and research settings. Yet questions remain about the pathways through which women are ultimately diagnosed with and treated for ADHD in adulthood, and very little is known about the benefits and costs of obtaining an ADHD diagnosis for women.

Qualitative research examining the firsthand experiences of women diagnosed with ADHD in adulthood may provide new opportunities to contextualize and better understand quantitative data showing increases in the diagnosis of ADHD (). There have been a few emerging qualitative studies focused on women’s experiences obtaining a diagnosis of ADHD focused primarily on young adulthood or later adulthood (; ; ). These studies have identified a number of converging themes, showing benefits associated with diagnosis of ADHD, including relief from finding an explanation for their difficulties and new opportunities to pursue treatment. However, this work has also identified significant barriers to accessing appropriate care. Notably, only one study, including five women with ADHD, has specifically examined diagnosis of ADHD among women in middle adulthood (). Given the precipitous rise in treatment for ADHD among women at this developmental period, there is a critical need to prioritize understanding the perspectives of women with ADHD during this time.

The goal of this study was to describe and interpret the shared experiences of women diagnosed with ADHD in adulthood. A mixed methods approach was used, in which quantitative and qualitative data was obtained from focus groups of women diagnosed with ADHD in adulthood. The research was aimed at understanding benefits and costs associated with obtaining the diagnosis. Factors hindering and facilitating the identification, assessment, and subsequent treatment of ADHD were also explored. It was intended that findings emerging from these groups would help to inform the development of future qualitative and quantitative research aimed at reducing barriers to care for females with ADHD.

Method

Women were recruited through social media postings advertising a study for women diagnosed with ADHD in adulthood. Participants were required to have been diagnosed with ADHD in middle adulthood (i.e., 29–55 years old), presumably past the developmental milestones of emerging adulthood (). Participants were required to live in the United States, have the capacity to provide consent, and English language proficiency. Informed consent and eligibility criteria were collected electronically. Diagnosis of bipolar disorder, autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorders was exclusionary. Eligible participants completed additional functional and demographic rating scales via a web-based survey platform, and were contacted by email to participate in a focus group. Participants completing all study procedures were compensated with a $50 gift card. All procedures were approved by the Penn State University Institutional Review Board and were consistent with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

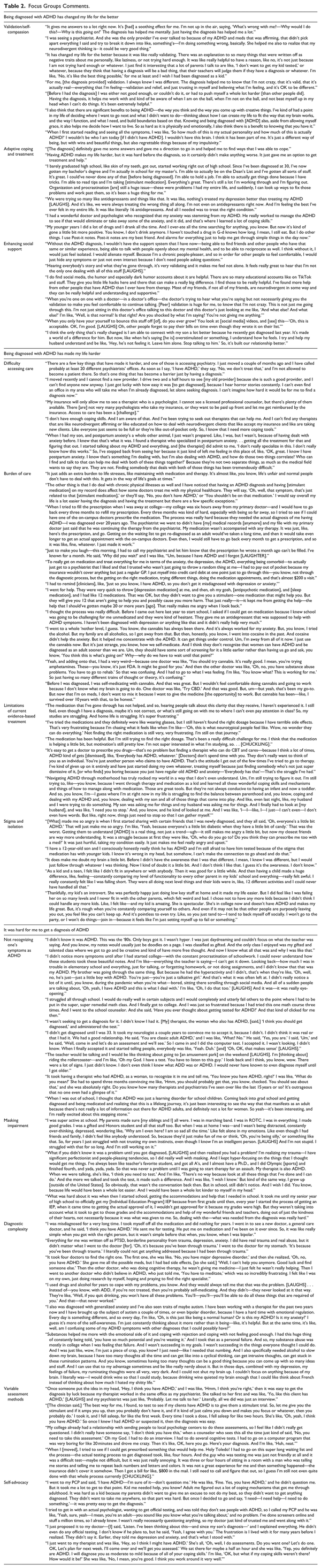

A total of 31 women provided consent, completed rating scales, and were eligible to participate; 21 were able to be contacted and scheduled to participate in the focus groups, with 14 attending the focus groups. There were no significant differences (p < .05) in current age, age of ADHD diagnosis, race, ethnicity, marital and employment status, ADHD severity, or treatment history between the women who did and did not participate in the focus groups. Diagnosis of ADHD was confirmed using the Adult Self-Report Scale () which includes all 18 symptoms of ADHD. Endorsed symptoms were summed, with four women meeting symptom count criteria for ADHD Inattentive Presentation, one meeting criteria for ADHD Hyperactive-Impulsive Presentation, and nine meeting criteria for ADHD Combined Presentation. The Impairment Rating Scale for Adults () was also administered to ensure that participants reported impairment (i.e., score of 3 or more) in at least two domains of functioning. Demographic and psychiatric characteristics of the women participating in the focus groups are presented in Table 1. All were diagnosed with ADHD in adulthood. Two participants were also diagnosed in childhood and they were included in this study because they had been required, upon initiating care in adulthood, to undergo assessment of ADHD again.

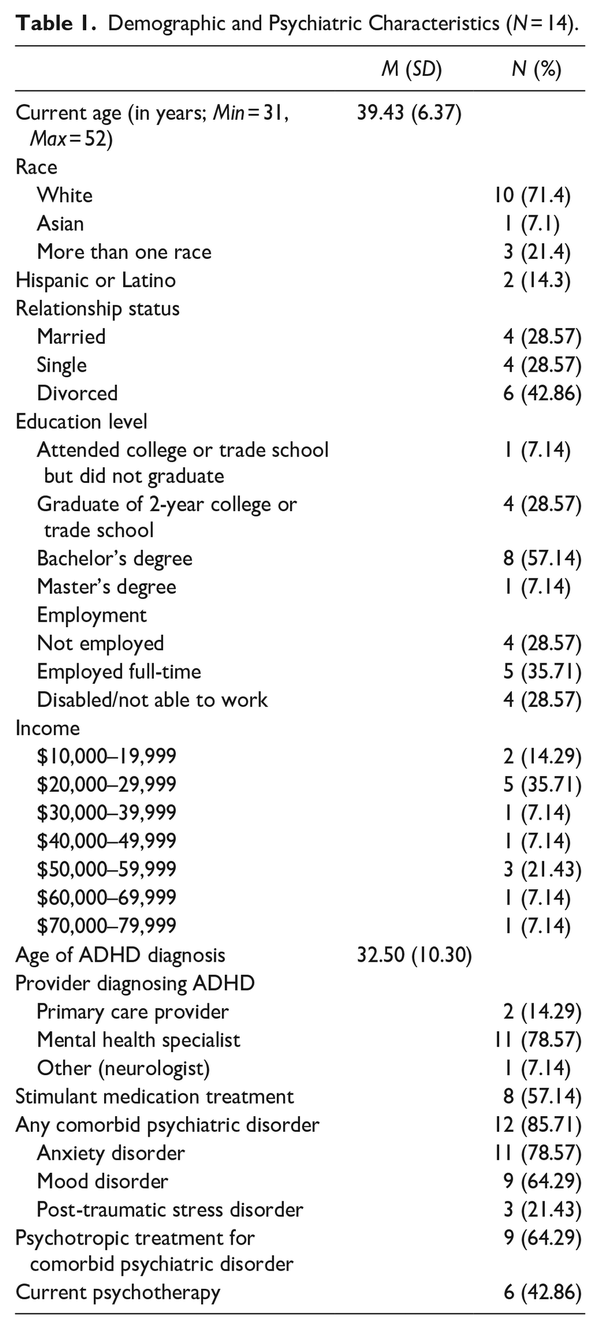

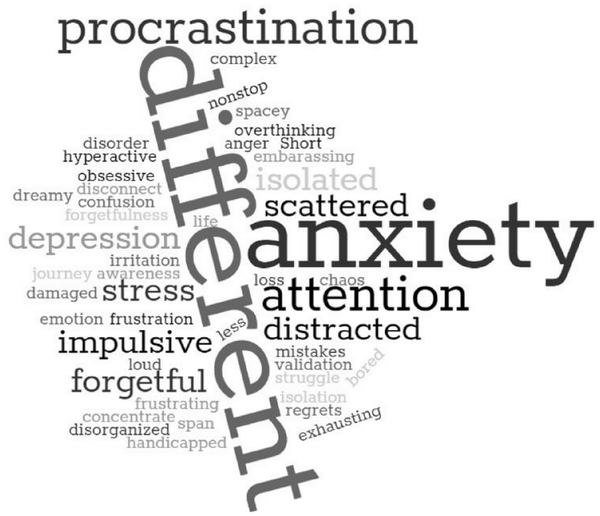

Two focus groups (eight participants in the first group, six in the second) were conducted via Zoom and were video recorded. Based on previous work (), two focus groups are sufficient to capture 80% of themes. Upon beginning the recording, confidentiality was discussed and participants were given the opportunity to change the presentation of their name to protect their anonymity. Explicit rules for camera use were not provided. Groups lasted 2 hr, and were semi-structured to include a brief introduction to the group facilitators and the study. Then, participants were asked to type open-ended responses to the ice breaker prompt, “What does ADHD mean to you?” Responses were collated into a word cloud and shared with participants (Figure 1). Next, participants selected forced choice responses of “yes,” “no,” or “not sure” to indicate their responses to the following statements: “Being diagnosed with ADHD has changed my life for the better,” “Being diagnosed with ADHD has made my life harder,” and “It was hard for me to get a diagnosis of ADHD.” Responses were used to facilitate group discussion. Both authors co-facilitated focus groups. The authors have extensive clinical and research experience focused on females with neurodevelopmental disorders, including ADHD and autism, allowing them to ask informed follow-up questions to facilitate discussion in the focus groups.

Figure 1

“What does ADHD mean to you?” Word cloud.

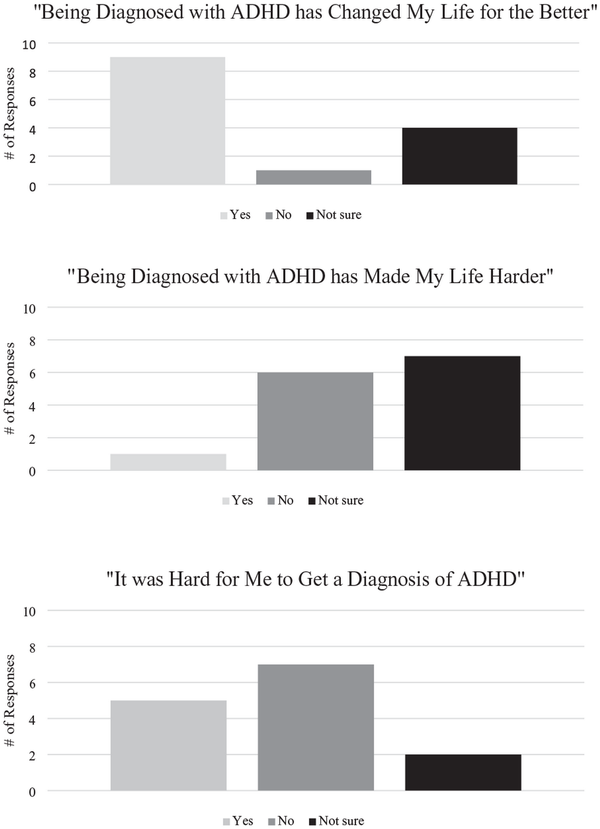

Focus group recordings were transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy. Transcripts were used for all coding activities. An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) framework was used to guide analysis of data collected from the focus groups (; ). IPA is focused on understanding a phenomenon through the perspective of those living with a particular condition, while also maintaining distance from the phenomenon in order to allow for critical analysis. In this approach, participants reflect on their own experiences and researchers subsequently attempt to make sense of individuals’ lived experience. Both authors coded study data. To analyze themes, they read through the transcripts independently in a series of steps, first to obtain a holistic perspective of each group, second to identify discussions that related to participants’ ADHD diagnosis while omitting off-topic discussion, and third to identify repeating ideas or codes. After identifying codes independently, they compared and discussed analyses, and refined a final list of common themes, which are presented in Table 2.

Results

Being Diagnosed With ADHD Has Changed My Life for the Better

Poll results are reported in Figure 2. A majority (64%) reported that receiving an ADHD diagnosis has changed their life for the better, and provided validation, increased self-compassion, new opportunities for adaptive coping and treatment, and greater social support. Some (29%) reported feeling unsure, and 7% denied that receiving the diagnosis had changed their life for the better.

Figure 2

Participant poll responses.

Prior to obtaining an ADHD diagnosis, women described receiving negative feedback from others who attributed their difficulties to aspects of personality or moral character that were within their control to change. Women reported that such interactions, repeated across their lives, led them to internalize negative views of themselves. Women shared that prior to diagnosis, they had long perceived themselves as being “different” and “not good enough” but had not understood why they had struggled across life domains. Receiving an ADHD diagnosis provided external validation for their struggles and new language with which they were able to make sense of their lived experience and more accurately explain their challenges to others. Many women described feeling relieved or soothed upon receiving their ADHD diagnosis.

Women also reported that diagnosis of ADHD made their life easier by providing access to treatments and support. Receiving stimulant medication, often after years of unsuccessfully trialing medications for alternative diagnoses and/or relying on self-medication with drugs, alcohol, or food, was described as life-changing by many. Women reported benefits of stimulant medication in their academic and occupational functioning, emotion regulation, depression, anxiety, impulsivity, and relationship functioning, as well as in their ability to parent effectively. Women identified effective medication management as being key for advancing opportunities to improve their quality of life, enabling them to be successful in seeking higher education and maintaining employment.

Receiving a diagnosis of ADHD also provided women with new opportunities to connect with others with the diagnosis, including family members, neurodivergent friends, as well as internet-based ADHD communities, often accessed via social media platforms. Women not only reported feeling a sense of community that reduced feelings of isolation, but also indicated that these connections were helpful for exchanging information and learning coping strategies that had not been otherwise available to them.

Being Diagnosed with ADHD Has Made My Life Harder

Although only 7% reported that diagnosis of ADHD made life harder, while 50% reported feeling unsure, and 43% disagreed with the statement (Figure 2), women identified several challenges upon receiving an ADHD diagnosis, including barriers to accessing appropriate care, particularly specialized mental health care. Women reported difficulty finding providers accepting new patients, especially providers willing to treat ADHD in adults, and even greater difficulty identifying providers with experience treating adult ADHD with common comorbid mental health conditions like anxiety and depression. Additionally, many women reported encounters with providers who were reluctant to prescribe stimulant medication or consider treating ADHD as their primary presenting problem. This was especially true when providers had more familiarity with other comorbid mental health conditions, such as anxiety and depression. Participants recalled that providers seemed more willing, and in some cases were insistent, that antidepressant, anxiolytic, and/or antipsychotic medications be trialed first in order to address comorbid mood and anxiety symptoms prior to, or instead of, initiating medication treatment for ADHD. Cannabis products were also discussed by providers before considering prescription medication for ADHD. Such care experiences left women feeling confused, invalidated, and ignored. For women who were able to obtain pharmacological treatment for ADHD, some noted challenges due to the confluence of executive functioning differences and the need to regularly schedule and attend medication management appointments, request prescription refills, and refill prescriptions on time. Women also reported shouldering significant out-of-pocket costs due to insurance restrictions, challenges navigating care with multiple providers, and barriers to continuity of care and long-term management of symptoms.

Some women described feelings of anger and disappointment upon recognizing the amount of time and resources spent, and suffering endured, while trialing medications that were ultimately unhelpful for their needs or accompanied by significant side effects. Additionally, many women voiced frustration regarding the apparent lack of evidence-based treatments beyond stimulant medication available for management of ADHD, and especially in the context of life transitions, such as becoming a parent. For these reasons, many participants indicated seeking out and relying upon alternative methods of managing ADHD symptoms, including self-medication with alcohol, cannabis, and other substances.

Women discussed feeling stigmatized by health care providers, friends, and family, who they felt did not take their ADHD diagnosis seriously. Women described increased self-doubt and low self-esteem due to increased self-awareness of their ADHD symptoms, and concerns about negative evaluation by others. Relatedly, women reported concerns about recognizing symptoms of ADHD in their children, and apprehension about seeking related care out of a desire to shield their children from the stigma and judgement they have endured.

It Was Hard for Me to Get a Diagnosis of ADHD

Half of the sample denied difficulty obtaining a diagnosis of ADHD, while almost 36% indicated the diagnostic process was difficult, and 14% were unsure (Figure 2). Yet regardless of the ease with which women obtained a diagnosis of ADHD, the majority reported initially being unaware that their experiences were indicative of ADHD. Many shared that for much of their lives, they had understood ADHD to be relevant only to White school-aged boys, and they had previously lacked awareness of how ADHD could present among females and in other cultural backgrounds.

Numerous factors were identified that hindered diagnosis of ADHD. Co-occurring psychiatric concerns, including depression, anxiety, trauma, as well as potential autism spectrum disorder, and chronic physical health conditions, complicated detection of ADHD among women themselves and their health care providers. Furthermore, some women disclosed substance use that further precluded accurate diagnosis of ADHD. Women also described receiving support from their parents and teachers, as well as their own conscientiousness and desire to please others, which likely masked earlier detection of ADHD.

Variable practices were used to diagnose ADHD, some of which are not necessarily evidence-based. While some women completed brief assessments, others completed extensive evaluations that were costly and burdensome. In a number of cases, ADHD was identified first by a trusted care provider, in one case a neurologist initially focused on treating another pre-existing condition, and in two other cases while working with female therapists, both of whom disclosed their own neurodivergence. For others, considerable self-advocacy after long-term struggles and self-directed psychoeducation about ADHD was required.

Discussion

This study is arguably the largest and most comprehensive mixed methods study examining the experiences of women diagnosed with ADHD during middle adulthood. Findings provide important insights to guide future research on ADHD in women. Women mostly reported that an ADHD diagnosis was beneficial, providing them with validation as well as new opportunities for coping and support. At the same time, some negative aspects of the diagnosis were also discussed, particularly difficulties accessing and maintaining care, negative treatment experiences, and stigma. Notably, women described variable diagnostic experiences, with many indicating that they had not recognized their own symptoms of ADHD, as well as diagnostic complexity and other factors that masked identification of ADHD. Women described a range of diagnostic assessment procedures, as well as considerable self-advocacy to convince their providers to consider the diagnosis of ADHD.

The themes that emerged in this study of women are consistent with those previously identified in other qualitative studies conducted primarily among younger and older adult women with ADHD (; ; ). Altogether this work points to considerable benefits as well as barriers to care for women with ADHD. This qualitative data provides critical firsthand perspective that is needed to contextualize extant quantitative findings showing marked increases in treatment for ADHD among adult women (; ; ). By integrating quantitative and qualitative data through mixed methods research, the current work strives to ensure that findings are aligned with and reflect the values, priorities, and interests of women with ADHD (). This is a notable advancement in the study of ADHD in women, as the majority of research on ADHD has prioritized school-aged boys. Our research group intends to use the themes identified from these focus groups to conduct one-on-one interviews with women with ADHD. Individual interviews may provide even more fine-grained detail on women’s experiences with ADHD beyond the findings that emerged from the focus groups.

This study included a relatively small sample and additional work is needed to expand the generalizability of these findings. For example, more than half of the women in the study were diagnosed with ADHD Combined Presentation and nearly 79% reported a co-occurring anxiety disorder, but consideration of other diverse presentations of women with ADHD are needed. Relatedly, only 14 of the 31 women eligible to participate in the study attended the focus group. Women self-selected for the study and were required to have been diagnosed with ADHD by a health professional, although more specific information on how diagnoses were made was not available. While self-reported symptoms of ADHD and related impairment were confirmed, emerging guidelines for first-time adult ADHD diagnosis recommend collection of additional assessments including informant ratings, chronicling a symptom timeline, and carefully ruling out alternative explanations for adult ADHD symptoms (). Additionally, other topics presumably relevant to understanding the diagnosis of ADHD in women (e.g., use of digital start-ups for pharmacological treatment, how ADHD diagnoses were established) were not directly addressed and member checking of results was not conducted. Additionally, while the focus of the study was on diagnostic experiences, there may be unique insight gained from further exploring the benefits and barriers to ADHD treatment among women. Despite these limitations, the mixed-methods approach, as described herein, helps to identify new priorities for research and ultimately to improve clinical care for women with ADHD. Based on the experiences disclosed by women in this study, several recommendations are provided to enhance the assessment and treatment of ADHD among women.

Recommendations to Improve Assessment of ADHD in Women

Increase Early Awareness of Female Expressions of ADHD

Despite enduring academic and peer difficulties throughout childhood, parents, educators, and primary care and mental health providers often failed to identify ADHD as a potential explanation for these challenges. Women also frequently had not considered ADHD to be relevant to their personal experiences, as they had viewed ADHD as a disorder relevant only to school-aged boys. There is a need for increased awareness of female expressions of ADHD (). While long-standing academic underachievement, difficulties forming and maintaining supportive relationships, and bullying may not be specific to ADHD, such factors should signal consideration of, and assessment for, ADHD, particularly in female youth.

Increase Screening for ADHD

When women expressed concerns about ADHD in clinical care, many described feeling invalidated by providers, who conveyed discomfort or a lack of familiarity with diagnosing ADHD in adulthood, minimized women’s concerns about ADHD, or were quick to identify and prioritize alternative explanations for symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity. Inattention is one of the most frequently reported mental health symptoms (; ), and it is important that clinicians, both specialized mental health providers as well as primary care providers, routinely screen for ADHD as they do for other common conditions such as depression and anxiety (; ) Several brief ADHD screening tools are freely available to providers and should be administered to validate women’s concerns and identify when ADHD may be relevant (; ). Screening for ADHD in primary care may help identify cases for which additional assessment is worthwhile, and help mitigate the many serious negative consequences () associated with not addressing ADHD.

Evidence-Based Assessment of ADHD in a Stepped-Care Approach

Women described various methods of diagnostic decision-making ranging from trialing stimulant medication to extensive assessment batteries, which were conducted in primary care and across a number of specialty practices, and often resulted in significant patient burden. Women also frequently lamented the amount of time they had struggled prior to receiving a diagnosis of ADHD. These accounts raise questions about the frequency with which providers rely on evidence-based practices to reliably diagnose ADHD in adulthood () and how decisions are made about who must undergo extensive assessment procedures in order to obtain a diagnosis and further care. In cases with relatively low psychiatric complexity or when a patient has been engaged with their provider for an extended time, diagnosis may be appropriately made in relatively brief clinical encounters in primary or specialty care, while more comprehensive specialty assessment may be reserved for more complex cases. A stepped-care approach would help reduce barriers to the diagnosis of ADHD for women and potentially conserve mental health care provider resources.

Consideration of Contextual Factors That May Mask ADHD

Women described a number of contextual factors, including placement in gifted programs in school that provided opportunities to engage in more creative and stimulating pursuits, family support with homework and organizational tasks, and family stressors, including family members (typically male) with more severe ADHD presentations, that may have obscured earlier detection of their own ADHD. Additionally, women described aspects of their behavior such as being perfectionistic “people pleasers,” as stemming from experiencing adversity, including bullying and other traumatic events, which led them to withdraw from their environment, and made their ADHD symptoms less salient to outside observers. Failure to consider the impact of such contextual factors may lead to false negative diagnoses of ADHD.

Recommendations to Improve Treatment of ADHD in Women

Treating ADHD Alongside Other Comorbidities

Despite evidence that anxiety, depression, substance use, and trauma are common with ADHD () and may develop as a consequence of undiagnosed and untreated ADHD, women reported that co-occurring conditions complicated their ADHD treatment or were prioritized above ADHD in treatment. Unlike these co-occurring conditions, ADHD requires evidence of impairment dating back to childhood (), suggesting that in many cases, ADHD may be the primary condition. Treating ADHD and addressing the broad functional impairments associated with ADHD, in school, at work, and in relationships, may greatly alleviate co-occurring difficulties such as anxiety and depression (). There is a dearth of research guiding management of ADHD and co-occurring conditions. Thus, patient choice should be considered in clinical decision-making about treatment sequencing.

Team-Based Care to Reduce the Burden of Treatment

Women described following-up for care with numerous providers to treat ADHD as well as a number of other psychiatric and physical complaints, such as sleep problems, disordered eating/weight concerns, and concerns about hormone changes during pregnancy and the menopausal transition. Multiple providers and appointments increase cost of care and risk for disjointed care that is difficult to maintain. As problems with sleep and eating are common among women with ADHD (), and hormonal fluctuations likely contribute to executive dysfunction which appears similar to ADHD (), models of integrated care that more comprehensively consider multiple concerns may lead to more streamlined and less burdensome care.

Accessible Alternative Approaches to Address ADHD

Although stimulant medication is the primary treatment for adult ADHD (), women discussed difficulties that were not sufficiently addressed with medication. Non-medication options may hold great benefit for women, particularly during developmental periods when stimulant medication treatment may be associated with significant risk, such as during pregnancy and while breastfeeding. However, relatively few clinicians provide psychosocial treatment for adult ADHD and insurance coverage limitations often restrict access to such care. Accumulating evidence shows benefits of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for adults with ADHD (; ). CBT focuses on changing maladaptive cognitive and behavioral patterns and has been studied, primarily as a treatment for depression and anxiety. As many women with ADHD experience clinical concerns such as low self-esteem, anxiety, depression, and trauma that co-occur with or result from ADHD in women, it is not surprising that CBT may be worthwhile. There is also emerging evidence that CBT specifically addressing executive dysfunction may reduce ADHD symptoms and related impairment (; ; ; ). CBT for executive dysfunction focuses on modifying the self-instructive cognitions and thereby behaviors that related to time management, organization, and planning, while also addressing maladaptive thoughts and behaviors that address co-occurring depression and anxiety (; ). CBT treatment is designed to be short-term and is offered in individual or group settings in which homework is assigned for outside of the therapy sessions to facilitate regular practice and generalization of CBT skills. Continued effort to examine CBT as a treatment for women with ADHD is worthwhile as are efforts to reduce potential barriers to effective treatment. For example, telehealth may be an ideal platform to deliver CBT for women with ADHD as it eliminates additional time for travel to treatment. Additionally, CBT that emphasizes acceptance of, rather than changing or minimizing, ADHD symptoms, may be beneficial given that ADHD symptoms follow a chronic course ().

Neurodiversity-Affirming Care

Women discussed the value of accepting their neurodivergence and attending to their strengths and resiliency. Rather than focusing on “fixing” their traits and behaviors, there may be relatively greater benefit to supporting women in seeking out environments in which they can present authentically and thrive (). Women described connecting with neurodivergent communities in their friendships and through social media. The brief, easily accessible, and stimulating format of social media content is ideally suited for individuals with attention and processing speed differences. Although the risk of misinformation exists on social media (), women indicated that exposure to neurodiversity-affirming social media accounts provided validation, reduced stigma, and helped motivate some women to initiate care for ADHD, especially when such critical support was lacking from providers. Additionally, social media content may provide women with ADHD, who are often socially isolated, with meaningful support and community. Women viewed ADHD affirming social media content as invaluable in the absence of other available supports, and indicated that the potential therapeutic utility of social media should not be overlooked by providers and researchers.

Author Contributions DEB and EJL conceptualized the study and collected and coded study data. DEB wrote the main manuscript text and DEB and EJL edited manuscript drafts. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data Availability De-identified data is available from the first author by reasonable request.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: DEB received consulting fees from Supernus Pharmaceuticals (unrelated to this project). EJL has no conflicts of interests to declare.

Funding The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Esther and Ling Tan Early Career Professorship awarded to DEB.

Dara E. Babinski

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0864-085X

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed.).

- Arnett J. J., Žukauskiene R., Sugimura K. (2014). The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18-29 years: Implications for mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(7), 569–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00080-7

- Babinski D. E., Saunders E. F. H., He F., Liao D., Pearl A. M., Waschbusch D. A. (2022). Screening for ADHD in a general outpatient psychiatric sample of adults. Psychiatry Research, 311, Article 114524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114524

- Barry M. J., Nicholson W. K., Silverstein M., Coker T. R., Davidson K. W., Davis E. M., Donahue K. E., Jaén C. R., Li L., Ogedegbe G., Pbert L., Rao G., Ruiz J. M., Stevermer J., Tsevat J., Underwood S. M., Wong J. B.; US Preventive Services Task Force. (2023). Screening for anxiety disorders in adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA, 329(24), 2163–2170. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00006

- Chronis-Tuscano A. (2022). ADHD in girls and women: A call to action – reflections on Hinshaw et al. (2021). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 63(4), 497–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13574

- Cornwall A., Jewkes R. (1995). What is participatory research? Social Science and Medicine, 41(12), 1667–1676. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00127-S

- Dalsgaard S., Ostergaard S. D., Leckman J. F., Mortensen P. B., Pedersen M. G. (2015). Mortality in children, adolescents, and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A nationwide cohort study. The Lancet, 385(9983), 2190–2196. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61684-6

- Danielson M. L., Bohm M. K., Newsome K., Claussen A. H., Kaminski J. W., Grosse S. D., Siwakoti L., Arifkhanova A., Bitsko R. H., Robinson L. R. (2023). Trends in stimulant prescription fills among commercially insured children and adults: United States, 2016–2021. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 72(13), 327–332. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7213a1

- Dawson A. E., Egan T. E., Wymbs B. T. (2020). Psychometric properties of the impairment rating scale in samples of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Assessment, 27(2), 384–403. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191117746502

- Faraone S. V., Rostain A. L., Blader J., Busch B., Childress A. C., Connor D. F., Newcorn J. H. (2019). Practitioner review: Emotional dysregulation in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder – implications for clinical recognition and intervention. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 60(2), 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12899

- Forbes M. K., Neo B., Nezami O. M., Fried E. I., Faure K., Michelsen1 B., Twose M., Dras M. (2023). Elemental psychopathology: Distilling constituent symptoms and patterns of repetition in the diagnostic criteria of the DSM-5 (pp. 1–23).

- Guest G., Namey E., McKenna K. (2017). How many focus groups are enough? Building an evidence base for nonprobability sample sizes. Field Methods, 29(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X16639015

- Guntuku S. C., Ramsay J. R., Merchant R. M., Ungar L. H. (2019). Language of ADHD in adults on social media. Journal of Attention Disorders, 23(12), 1475–1485. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054717738083

- Hamed A. M., Kauer A. J., Stevens H. E. (2015). Why the diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder matters. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 6, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00168

- Henry E., Jones S. H. (2011). Experiences of older adult women diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Women and Aging, 23(3), 246–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2011.589285

- Holthe M. E. G., Langvik E. (2017). The strives, struggles, and successes of women diagnosed with ADHD as adults. SAGE Open, 7(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017701799

- Jensen C. M., Steinhausen H. C. (2015). Time trends in incidence rates of diagnosed attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder across 16 years in a nationwide Danish registry study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76(3), e334–e341. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.14m09094

- Kessler R. C., Adler L., Ames M., Demler O., Faraone S., Hiripi E. V. A., Howes M. J., Jin R., Secnik K., Spencer T., Ustun T.B., Walters E. E. (2005). The World Health Organization adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS): A short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychological Medicine, 35(2), 245–256. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291704002892

- Kessler R. C, Adler L., Barkley R., Biederman J., Conners C. K., Demler O., Faraone S. V., Greenhill L. L., Howes M. J., Secnik K., Spencer T., Ustun T. B., Walters E. E., Zaslavsky A. M. (2006). The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(4), 716–723. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.716

- Knouse L. E., Teller J., Brooks M. A. (2017). Supplemental material for meta-analysis of cognitive–behavioral treatments for adult ADHD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(7), 737–750. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000216.supp

- Lefler E. K., Sacchetti G. M., Del Carlo D. I. (2016). ADHD in college: A qualitative analysis. ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 8(2), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-016-0190-9

- Liu C. I., Hua M. H., Lu M. L., Goh K. K. (2023). Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural-based interventions for adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder extends beyond core symptoms: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 96(3), 543–559. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12455

- Morgan J. (2023). Exploring women’s experiences of diagnosis of ADHD in adulthood: A qualitative study. Advances in Mental Health. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/18387357.2023.2268756

- Owens E. B., Zalecki C., Gillette P., Hinshaw S. P. (2017). Girls with childhood ADHD as adults: Cross-domain outcomes by diagnostic persistence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(7), 723–736. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000217

- Safren S. A., Sprich S. E., Perlman C. A., Otto M. W. (2017). Mastering your adult ADHD: A cognitive-behavioral treatment program. Oxford University Press.

- Shanmugan S., Epperson C. N. (2014). Estrogen and the prefrontal cortex: Towards a new understanding of estrogen’s effects on executive functions in the menopause transition. Human Brain Mapping, 35(3), 847–865. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.22218

- Sibley M. H. (2021). Empirically-informed guidelines for first-time adult ADHD diagnosis. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 43(4), 340–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803395.2021.1923665

- Sibley M. H., Faraone S. V., Nigg J. T., Surman C. B. H. (2023). Sudden increases in U.S. stimulant prescribing: Alarming or not? Journal of Attention Disorders, 27(6), 571–574. https://doi.org/10.1177/10870547231164155

- Siu A. L., Bibbins-Domingo K., Grossman D. C., Baumann L. C., Davidson K. W., Ebell M., García F. A. R., Gillman M., Herzstein J., Kemper A. R., Krist A. H., Kurth A. E., Owens D. K., Phillips W. R., Phipps M. G., Pignone M. P. (2016). Screening for depression in adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association, 315(4), 380–387. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.18392

- Smith J., Eatough V. (2007). Interpretive phenomenological analysis. In Lyons E., Coyle A. (Eds.), Analysing qualitative data in psychology (pp. 35–50). Sage Publications.

- Solanto M. V. (2011). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult ADHD: Targeting executive dysfunction. Guilford Press.

- Sonuga-Barke E. J. S. (2023). Paradigm ‘flipping’ to reinvigorate translational science: Outlining a neurodevelopmental science framework from a ‘neurodiversity’ perspective. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 64(10), 1405–1408. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13886

- Ustun B., Adler L. A., Rudin C., Faraone S. V., Spencer T. J., Berglund P., Gruber M. J., Kessler R. C. (2017). The world health organization adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder self-report screening scale for DSM-5. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(5), 520–526. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0298

- Vincenti S. C., Galea M., Briffa V. (2023). Issues which marginalize females with ADHD: A mixed methods systematic review. Humanities and Social Science Research, 6(2), 30. https://doi.org/10.30560/hssr.v6n2p30

- Visser S. N., Danielson M. L., Bitsko R. H., Holbrook J. R., Kogan M. D., Ghandour R. M., Perou R., Blumberg S. J. (2014). Trends in the parent-report of health care provider-diagnosed and medicated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: United States, 2003-2011. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 53(1), 34–46.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.001

- Weiss M. D., Weiss J. R. (2004). A guide to the treatment of adults with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 65(3), 27–37.