International students are individuals who leave their home country and travel to another for the purpose of study as temporary citizens (; ). Their number has increased substantially by as much as 50% globally between 2005 and 2012, with an estimated total number reaching more than 5 million in 2016 (). International students act as ambassadors, promote education diversification, bring financial benefits to the host countries, and return to their home countries with advanced knowledge and a global perspective, thereby increasing intellectual and social capital ().

However, studying abroad comes with many challenges, including academic demands and acculturation pressures (). During their stay, international students make decisions about how to negotiate their cultural belongingness, with implications for their psychological and sociocultural adjustment to the host society (). Importantly, international students’ adjustment can be psychologically problematic: Previous research revealed that international students experience more mental health problems than local students ().

To understand how individuals deal with acculturative processes, distinguished between acculturation conditions, orientations, and outcomes. A central outcome of acculturation is psychological adjustment, which refers to feelings of well-being and life satisfaction in the host culture (; ). Acculturation conditions include social support, language ability, length of residence, personality, gender, and country of origin. Among these, the relation between social support and psychological adjustment has been particularly extensively investigated by scholars (; ; ; ; ; ).

Although there is a substantial body of evidence on the relationship between social support and psychological adjustment among international students, to our knowledge, no meta-analysis has been conducted on their relationship in this population. A systematic overview would be particularly helpful as researchers have used diverse constructs, measurements, and outcome variables to study the effect of social support on psychological adjustment (; ). We, therefore, set out to study (a) the overall association between social support and psychological adjustment, (b) how different types and sources of social support moderate the relationship between social support and psychological adjustment, and (c) whether the relationship between social support and psychological adjustment holds across different operationalizations of psychological adjustment.

We expect to find a positive overall relationship between social support and psychological adjustment of international students. Among various nonmigrant populations, an overall positive association between social support and health has been reported by multiple meta-analyses including adult general population samples (), children and adolescents (), individuals in organizations (), patients (), and people suffering from traumatic experiences (). As suggested, social support not only directly promotes mental health but also indirectly contributes to well-being by providing buffering resources for individuals experiencing stressful life events, such as going abroad to study as an international student. This particular relation is widely studied, but without any meta-analytic review.

Such insights are not only helpful in regard to international students, who are often at risk (), but could also offer valuable information regarding other sojourning groups such as expatriate workers (diplomats, aid workers, guest workers, business executives; ). These groups are in a similar position, such that they are temporarily staying in a host culture with a particular purpose (e.g., work). Although they are comparable with international students in many respects, they may enter their new environment under less well-organized circumstances. Universities often have well-organized exchange programs and offer institutional support, whereas this may not always hold true for most companies or humanitarian organizations hosting foreign employees. In the following, we outline the relationship between social support as an acculturation condition and psychological adjustment as an acculturation outcome.

Support and Psychological Adjustment in the Acculturation Process

Acculturation at the individual level is the dual process of sociocultural and psychological change in relation to host and heritage culture as the result of contact with people from different cultural backgrounds (). Acculturation conditions include personal characteristics (e.g., age, length of stay, personality) and situational context (e.g., social support, stressful situations). Acculturation orientations include cultural adoption to the host context (i.e., the extent to which contact with the host context is sought) as well as cultural maintenance (i.e., the extent to which the heritage culture is maintained), and influence the link between conditions and outcomes. Acculturation outcomes consist of psychological well-being and sociocultural competence in both host and heritage domains (). For the present study, we focus especially on social support as an acculturation condition that influences international students’ psychological adjustment as an acculturation outcome. We further included personal characteristics of the international student (age, length of stay) and cultural distance between host and heritage cultures as acculturation conditions influencing international students’ psychological adjustment. Cultural distance is the perceived discrepancy between social and physical aspects of home and host culture environments () and is found to be related to a variety of acculturation attitudes and outcomes (). For example, exchange students who perceive fewer differences between the home and host cultures fare better in terms of their sociocultural adjustment ().

Social Support as an Acculturation Condition

Social support is the provision of both psychological and tangible resources to satisfy an individual’s need for concern, approval, belonging, and security (; ). In the review work by , they proposed that social support has a positive association with well-being by offering regular positive experiences and buffering life stressors. Although most findings supporting this relationship are correlational, and, therefore, cannot indicate causality (), a meta-analysis by examining manipulated social support in laboratory settings revealed that social support improves health-related indicators (e.g., heart rate, blood pressure). Although general evidence for a positive, or even causal, relationship between social support and psychological well-being is mounting, it is unclear which types and sources of social support may be most effective.

Social support has been described as a meta-construct, covering diverse operationalizations (). In the current context, we posit that these different conceptualizations may moderate the effect of social support on psychological adjustment: For instance, found that perceived social support (e.g., perceived support from family and friends) and received affective support (had intimate interactions, received advice or positive feedback) were positively related to well-being, whereas received instrumental support (e.g., received material aid, physical assistance) had a negative impact on well-being. It is, therefore, important to assess different types and sources of social support. In the following, we distinguish two major domains of variations: support type and support source.

Support Type

Social support can be assessed objectively and subjectively (). Objective social support is typically assessed via self-reports of either the actual received social support or the size of the individual’s social network. Received social support consists of supportive behaviors provided by one’s network (). An example item for received social support is “Think about the person who is closest to you, such as your spouse, partner, child, friend, and so on. How did this person react to you during the last week?” (). Participants then select from a list what best describes the interaction (e.g., “This person was there when I needed him or her.”). Social network is a proxy for potential support, indexed by network size and strength (e.g., number of friends and frequency of interactions).

Unlike the objective assessment of actual support provided by others, subjectively measured social support probes the perceptions and interpretations of the individual receiver (). Subjective social support is commonly measured as either perceived social support or sense of social integration or connectedness (; ). Perceived social support taps an individual’s perceptions of the general availability of potential support. An example statement would be “I can count on my friends when things go wrong” (). Sense of social connectedness measures one’s feeling of relatedness toward other people; a reverse-coded example question is “I feel so distant from people” ().

Subjective and objective social support seem to be two distinct constructs, which are not necessarily highly intercorrelated. A meta-analysis by found an average correlation of r = .35. Another meta-analysis, showcasing the need to differentiate between objective and subjective social support, has shown that subjective social support has a stronger positive relationship with mental health than objective social support (). We, therefore, consider both subjective and objective types of social support as potential moderators of the link between social support and psychological adjustment of international students. We also test the effect of mixed sources of support, as in some studies, the two types of support sources were jointly measured, rather than separately.

Support Source

A further variation in social support concerns the source of support. Researchers often assume that interactions with one’s social network are generally supportive (). However, network functions vis-à-vis international students’ psychological adjustment may depend on the source. Research on international students distinguishes between support from the conational (individuals from same heritage culture) and host networks (individuals from the host culture). found that strong ties with individuals from the same ethnicity group (closely resembling a conational source) improved international students’ self-esteem and helped them adapt to American society. similarly showed that support from conational friends helped international students stabilize emotions by offering feelings of belongingness. This, however, may come at a cost: argued that international students may be less motivated to adjust to the host culture if their heritage culture identities are frequently reinforced. even found that intensive conational friend networks are negatively related to international students’ life satisfaction and contentment.

Most studies on support from the host network report that support from host sources promotes international students’ well-being (; ; ; ). There are also studies suggesting that it may be useful to go beyond host and conational sources of support and investigate fellow international students as a potential source of support, which prompted us to include this category (e.g., ; ; ). Given the variety of relationships between different sources of social support and psychological adjustment, we opted to include the source of support in the current meta-analytic review as an additional moderator. We differentiated between host, conational, and international sources of support, as well as multiple mixed sources (if support from various groups was measured in one measurement) and unspecified support sources (if the sources of social support were not clearly reported).

Psychological Adjustment as an Acculturation Outcome

As one of the acculturation outcomes, psychological adjustment reflects the psychological changes that international students go through in the acculturation process (; ). Psychological adjustment can be operationalized either positively (e.g., well-being) or negatively (e.g., mental health problems). The two most often used indicators of positive psychological adjustment are self-esteem and life satisfaction (; ). Negative psychological adjustment can come in the form of acculturative stress (), somatic problems (such as headaches and sleeplessness; ), or psychiatric symptoms (such as depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation; ; ; for a general overview, see ). Accordingly, researchers evaluate international students’ psychological adjustment with a number of different indicators in their studies (; ; ; ).

Although there is good reason to believe that social support promotes psychological adjustment (), its influences on negative mental health versus positive well-being may be different. For example, meta-analytic review of findings regarding the general population in Taiwan found that social support excels at shielding from mental health problems, but only moderately enhances well-being. It seems that social support becomes more valuable during adversity. Given the multitude of challenges international students go through, it is of importance to see whether there is a similar difference in the relationship between social support and positive and negative psychological adjustment.

Overview of the Current Research

Despite a growing body of literature on the importance of social support among international students, the relationship between social support and international students’ psychological adjustment has not yet been systematically assessed. We expect that social support is an important acculturation condition affecting international students’ psychological adjustment. We set out to provide a summary of previous studies to guide further research on the topic. For that end, we carried out a meta-analysis and have assessed (a) the overall relationship between social support and international students’ psychological adjustment and (b) whether social support type (objective, subjective, mixed), source (host, conational, international, unspecified), and demographic moderators (age, length of stay, cultural distance) affect the direction or magnitude of that relationship. Given the heterogeneity of empirical findings regarding support source, we did not specify expectations regarding which support source would be most associated with acculturation outcomes. Because findings regarding support type are more homogeneous, we specifically expected that subjective social support be linked to better acculturation outcomes than objective social support (in line with ; ). Finally, we assessed (c) whether the relationship between social support and psychological adjustment can be generalized across positive and negative operationalizations of psychological adjustment.

Method

Below, we describe how we conducted the literature search, the inclusion criteria, and how studies were coded. We conclude with a section on how the effect sizes were identified and computed.

Literature Search

Location of relevant studies

In Step 1, a literature search was conducted using EBSCO and Web of Science using the key words “international,” “exchange,” “overseas,” or “foreign” and “well-being,” “mental health” “psychological adaption,” “psychological adjustment,” “mood,” “affect,” “emotion,” “distress,” “strain,” “depression,” “stress,” “anxiety,” “loneliness,” “homesickness,” “symptoms,” “illness,” “disease,” “life satisfaction,” “self-esteem,” or “happiness,” and “students.” We chose to be as inclusive as possible in the choice of how researchers have adopted definitions and measurements of psychological adjustment (but studies had to specifically refer to psychological adjustment, see below). The literature search started on November 11, 2016, and was completed June 12, 2018, and is inclusive of articles published up to that date.

Inclusion criteria of articles

Two rounds of data inclusion were conducted to maximize the coverage of studies that examine the relationship between social support and psychological adjustment in an international student sample. The selection criteria in Round 1 dictated that the article was (a) written in English, (b) published in peer-reviewed academic journals or academic conferences, (c) applied quantitative methods, and (d) investigated psychological adjustment, broadly operationalized (e.g., distress, life satisfaction, psychological adaption), of international students. Inclusion criteria in Round 2 were that articles (e) examined the relationship between social support and at least one indicator of psychological adjustment (e.g., depression, self-esteem, well-being) and (f) provided the effect size (ES) of a bivariate Pearson correlation coefficient r or sufficient statistical information for the estimation of correlation r (i.e., standardized regression coefficient β and structural equation modeling [SEM] path coefficient βsem).

The database search resulted in 45,963 search results. These search results were manually inspected to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria. A total of 77 articles met the inclusion criteria, but one paper was excluded because correlations were only reported for subsamples, and not the entire participant sample. In the end, 76 articles (all publications contain one study, except one publication by , which contains two) formed the basis of analyses in this study. Studies contributing effect sizes to meta-analyses are marked with an asterisk in the references

Data Coding

The following information was extracted from the studies: (a) publication source (i.e., authors, journal name, publish year); (b) sample size, ethnicity, gender, average age, and sojourning location; (c) social support (i.e., types and sources) and psychological adjustment (i.e., instruments, valence of indicators); (d) original type and magnitude of effect sizes. Coding of social support types and sources as well as psychological adjustment was carried out independently by the first and third authors. Across these variables and all included studies, there was a 97.34% agreement between the coders (seven disagreements in 264 units). Disagreements were resolved via discussion between the first, second, and third authors.

Social support type

Social support types were coded into three categories. First, studies were coded as objective social support when they measured social support using one (or more) of three objective indicators: (a) the number of people in one’s social network, (b) actual contacts/interactions/encounters with other people, and (c) received social support such as information from university and financial help from friends. Studies were labeled as assessing subjective social support when they included one (or more) of five subjective indicators: (a) perceived social support, (b) satisfaction with support offered by network, (c) emotional support, (d) social integration (e.g., with friends, sports clubs), and (e) sense of social connectedness. Studies received the label mixed social support when they jointly measured social support using both objective and subjective dimensions. For example, measured participants’ social interactions with other people (objective social support) and their sense of social connectedness (subjective social support) on one scale without reporting separate scores.

Social support source

Five categories of social support were differentiated. Social support was labeled as (a) conational when they measured support from family members or conational friends, irrespective of locations or (b) host when they measured support from host–national friends or (c) other international friends and international host organizations or (d) mixed sources (when data are not reported separately for the sources), and (e) unspecified sources when the studies measured social support without specifying the support source. This occurred, for instance, when perceived social support was measured from all potential sources using items such as “how many people near you do you feel close to and trust” ().

Psychological adjustment

We differentiated between two operationalizations of psychological adjustment: (a) positive, for relationships between social support and positive indicators of psychological adjustment (e.g., satisfaction with life); or (b) negative, for relationships between social support and negative psychological adjustment (e.g., acculturative stress).

Cultural distance

Cultural distance has been typically characterized as aspects of psychological and physical functioning that are perceived to be different between cultural contexts (, see also ), and has been most widely compared between Western and (east) Asian nations (). There is no methodological consensus yet on the assessment of perceived cultural distance, although there are new efforts in this direction that attempt to specify more objective criteria for cultural distance (see ). Studies in the present meta-analysis rarely included measures on perceived cultural distance; we therefore, in line with the extensively researched distinction between Asian and Western nations, separated three prototypical distances from one another: (a) high, for instance, Asian international students studying in Western context; (b) low, for example, Asian international students in Asian countries; and (c) undefined, in case there is no specification of the cultural background of the students. This categorization represents only a crude proxy for more direct measures. Consensus or meta-analytic findings on measures of cultural distance across cultural contexts are so far still lacking.

Effect Size Calculation

Effect sizes correlation r for the relationship between social support and psychological adjustment were calculated. Of the 76 studies, 60 studies reported Pearson correlation rs, 15 provided standardized regression coefficients β, and one study reported SEM path coefficient βsem. First, all original effect sizes were converted to correlation r (). Then, correlation r values were converted to Fisher’s z to adhere to the assumption of normally distributed observed effect.

For longitudinal studies, only effect sizes at the end of the sojourning period were used. If effect sizes were reported for both the total scale (e.g., acculturative stress) and separate dimensions (e.g., perceived discrimination, fear, stress due to change), effect sizes of the subscales were chosen.

Effect sizes for the relationship between social support and negative operationalized measures of psychological adjustment were reversed so that effect sizes for positive and negative indicators could be directly compared. Hence, a positive effect size is always interpreted as social support benefiting psychological adjustment, irrespective of the valence of psychological adjustment.

Data Analysis

We conducted random multilevel effect meta-analyses using the metafor package () in R (). As mentioned before, we gathered multiple effect sizes per study. Because effects within a study are often from the same sample of participants, the independency of effect sizes assumption from standard meta-analytic techniques is violated. To appropriately incorporate this multilevel structure, that is, account for the dependency of the effect sizes, we conducted (random) three level meta-analytic models (see ).

Regarding moderator analyses, dummy coding was used. For social support type, objective support was used as the reference category. For social support source, conational support was the reference group. For cultural distance, it was “undefined,” the largest group in terms of sample size. Finally, positive adjustment was used as the reference category for the effect of psychological adjustment valence.

Results

We set out to determine (a) the overall effect size of the relationship between social support and international students’ psychological adjustment, whether (b) different types and sources of social support affect the relationship between social support and international students’ psychological adjustment, and whether (c) the relationship between social support and international students’ adjustment is identical for both positive and negative outcomes of psychological adjustment. We also explored whether the relationship between social support and adjustment is moderated by cultural distance.

Before we turn to these main questions, we provide a profile of the studies included in the meta-analysis, including participant, study, and measurement characteristics. After that, we consider publication bias and test for outliers. Finally, we turn to the meta-analysis.

Descriptive Characteristics

Sample characteristics

Sample sizes across all 76 studies ranged from 36 to 1,172, median = 166. The total number of participants was 16,136. There are 35 studies that investigated international student sample with multiple nationals, 38 studies focused on Asian groups, and only three studies focused on European samples. The average age of the sample was reported by 64 studies, with a mean age weighted by sample size of 24.12 years (SD = 3.03 years). Average length of stay was reported by 39 studies, with a weighted average length of 22.58 months (SD = 11.70 months). In the 68 studies that reported gender, the percentage of female participants ranged from 24.1% to 82.2%.

Study characteristics

The final sample of 76 studies came from 50 journals, one conference proceeding, and one unpublished dissertation. Nine journals contributed more than one study (e.g., 14 studies came from the International Journal of Intercultural Relations). There were six studies (7.89%) before 1991, seven studies (9.21%) between 1991 and 2000, 24 studies (31.58%) between 2001 and 2010, and 39 studies (51.32%) between 2011 and 2018. Most studies investigated international students studying in the United States (k = 42, 55.30%), followed by Australia (k = 9, 11.80%), Canada, China, Japan, Malaysia, and the United Kingdom. Several studies investigated multiple destinations on a global scale (k = 5, 6.58%). The remaining sojourning destinations included Russia, Norway, New Zealand, Ghana, France, and Denmark.

Social support measures

Of the 257 effects, 169 involved (65.76%) subjective social support, 83 (32.40%) involved objective social support, and five (7.95%) involved mixed social support. A sizable proportion of the studies (k = 30, 39.47%) specifically developed a set of items to evaluate social support in the sample rather than employing an existing scale. The most frequently used scales for social support were the Social Connectedness Scale (SCS; ; k = 11, 14.47%) and the Index of Social Support (ISS; ; k = 8, 10.53%).

Psychological adjustment measures

A total of 24 different indicators of psychological adjustment were used in the current sample of studies, including positive (self-esteem, well-being, positive psychological adjustment, life satisfaction, positive affect, and contentment) as well as negative indicators (acculturative stress, psychological symptoms, psychosomatic symptoms, stress events, perceived stress, negative affect, distress, depression, anxiety, homesickness, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation). There were 26 studies that employed more than one indicator. Forty-one (53.95%) studies applied only negative indicators, 17 (22.37%) studies only employed positive indicators, and 18 studies (23.38%) used both positive and negative indicators. The two most frequently used indicators of positive psychological adjustment were well-being and self-esteem, mostly measured by the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; ; k = 13, 17.11%) and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; ; k = 8, 10.53%). The two most often used indicators of negative psychological adjustment were acculturative stress, predominantly measured by the Acculturative Stress Scale for International Students (ASSIS; ; k = 10, 13.16%); and depression, mostly measured by the Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D; ; k = 9, 11.84%).

Overall Association Between Social Support and Psychological Adjustment

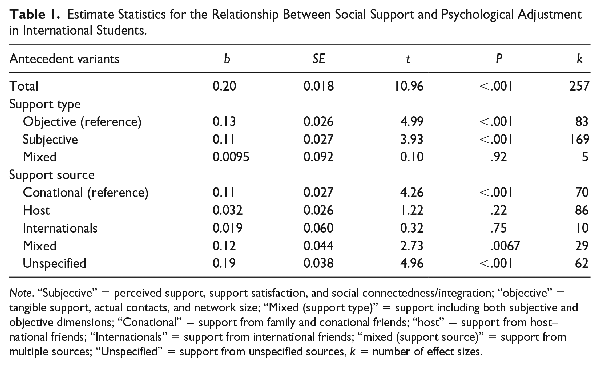

A multilevel random-effects model was applied to examine the overall relationship between social support and psychological adjustment (Table 1). The average weighted effect size was found to be statistically significant, b = 0.20, SE = 0.018, t = 10.96, p < .001, 95% confidence interval (CI) = [0.16, 0.24]. This reveals that social support is positively related to psychological adjustment for international students.

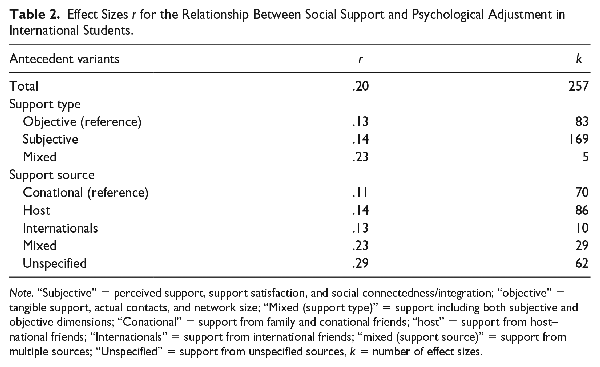

In terms of the variability in the sample, the test for heterogeneity of the effects revealed significant heterogeneity, Q(256) = 1,662.91, p < .001, The between-study variance is σ2 = 0.015, 95% CI = [0.0078, 0.025], and the variance between-effect sizes within studies is σ2 = 0.017, 95% CI = [0.013, 0.023], making the total variance 0.032. In terms of percentages, 38.98% of the variance can be attributed to differences between studies and 45.94% of the variance can be attributed to differences between effect sizes within studies. These findings suggest the presence of moderators (Table 2).

Analysis of Publication Bias and Outliers

Publication bias

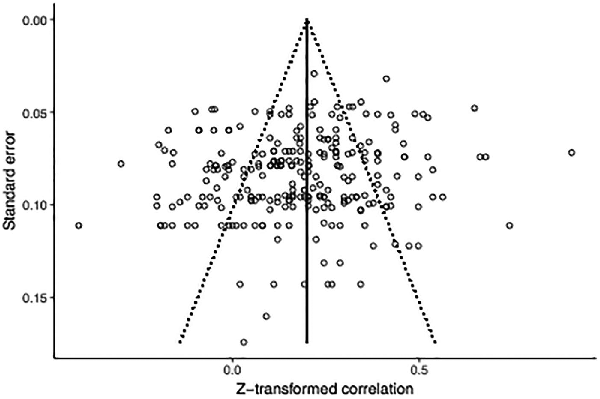

We tested for the presence of publication bias using Egger’s test (; ). We used the inverse of the standard error as a moderator of the effect of social support on psychological adjustment. Results suggest that there is a publication bias, as seen in a significant effect of the intercept, b = 0.14, SE = 0.058, t = 2.38, p = .018, 95% CI = [0.024, 0.25]. Inspection of the funnel plot (see Figure 1) reveals that the asymmetry is caused by the presence of a larger number of smaller and negative effects of social support on psychological adjustment. In other words, this could suggest that published studies are underestimating the effect size of social support.

Figure 1

Funnel plot of the effect sizes. Please note that the funnel plot does not reflect the multilevel structure of the effect sizes. For a colored version that does reflect the multilevel structure, see the Supplemental Material.

Outliers

The presence of extreme effect sizes can distort the result of meta-analyses. We, therefore, conducted model diagnostics, including Cook’s distances, hat values, and standardized residuals (see supplemental material). No outliers were found.

Influence of Different Types and Sources of Social Support on the Effect Size

As suggested by the heterogeneity analyses, we turned next to the investigation of moderators.

Type of social support

Social support type significantly influenced the magnitude of effect sizes, F(2, 254) = 7.99, p < .001. Relative to objective social support, subjective social support is more strongly related to psychological adjustment, b = 0.11, SE = 0.027, t = 3.93, p < .001, 95% CI = [0.053, 0.16]. Social support of mixed type was not found to differ from the relationship between objective social support and psychological adjustment, b = 0.0095, SE = 0.092, t = 0.10, p = .92, 95% CI = [−0.17, 0.19].

Source of social support

Sources of social support influenced the magnitude of effect sizes, F(3, 252) = 8.20, p < .001. Relative to conational support, support from a mix of sources was found to be associated with a stronger effect on psychological adjustment, b = 0.12, SE = 0.044, t = 2.73, p = .0067, 95% CI = [0.034, 0.21]. Support from unspecified sources was also found to be more positively related to psychological adjustment, relative to conational support, b = 0.19, SE = 0.038, t = 4.96, p < .001, 95% CI = [0.11, 0.26].

Support from hosts or internationals was not found to be more or less positive than the effect of conational support on psychological adjustment, hosts: b = 0.032, SE = 0.026, t = 1.22, p = .22, 95% CI = [−0.020, 0.084]; internationals: b = 0.019, SE = 0.060, t = 0.32, p = .75, 95% CI = [−0.10, 0.14].

Correlations Across Different Operationalizations of Psychological Adjustment

No significant moderation was found of the valence of the psychological outcome measure, F(1, 255) = 1.14, p = .29.

Cultural Distance and Personal Characteristics

Similarly, no moderating effect of cultural distance was found, F(2, 254) = 1.53, p = .22. Finally, age and length of residence were not found to be significant moderators, age: F(1, 62) = 2.29, p = .14; length of residence: F(1, 37) = 0.074, p = .79. However, the percentage of female participants in the sample did moderate the relationship between social support and psychological adjustment, F(1, 66) = 4.78, p = .032. A larger percentage of female participants was associated with a stronger effect of social support on psychological adjustment, b = 0.0037, SE = 0.0017, t = 2.19, p = .032, 95% CI = [0.00032, 0.007].

Discussion

The present meta-analysis statistically synthesized 257 effects from 76 empirical studies that reflect the relationship between social support and international students’ psychological adjustment. We applied the framework by to investigate the effect of social support types and sources (as an acculturation condition) on international students’ positive and negative psychological adjustment (as acculturation outcomes). We found an overall association between social support and international students’ psychological adjustment, with a significant positive overall effect size (r = .20, 95% CI = [0.16, 0.23]), of a small-to-moderate magnitude (, ). This effect held across differently valanced operationalizations of psychological adjustment (positive and negative). Type and source of social support, however, emerged as moderators. Subjective social support was found to be associated with more psychological adjustment compared with objective and mixed social support. Regarding the source of social support, both a mix of different sources of social support and unspecified sources of social support were related to more psychological adjustment.

The magnitude of the relationship is consistent with other meta-analyses examining the relationship between social support and individual’s mental health in other populations. reported a correlation of −.16 between stress and social support by meta-analyzing 29 studies; found a correlation of .18 between social support and children and adolescents’ well-being; and reported effect sizes for the relationship between work–family conflict and different sources of support ranging from −.15 to −.36. The effect of social support is consistently positive across different types and sources of support and across various populations. Finding a small-to-moderate overall effect size also means that studies investigating this association should pay close attention to sample size to ensure sufficient power. Based on G*power calculations (), a sample size of 191 participants is required for 80% statistical power to find an effect of r = .20 at significance level of .05. Of the studies included in the current meta-analysis, only 32 (42.11%) met this requirement.

Moderators of Social Support: Type and Source

Researchers have proposed that subjective social support reflects an individual’s specific cognitive appraisal of the surrounding environment, and may be better suited to predict people’s well-being (; ; see also the meta-analysis by ). hypothesized that objective social support received by individuals may trigger feelings of dependency, and may, thus, not benefit well-being as much as subjectively interpreted social support. We, therefore, expected subjective social support to have a stronger positive association with psychological adjustment than objective social support. And indeed, we obtained such a pattern. All types of social support have a positive impact on psychological adjustment, but subjective support has a stronger positive association than objective social support. That is, international students who perceived more social support, who felt more emotional support, or who were more satisfied with the provided support were those who reported better psychological adjustment (for similar findings among adolescents, see ).

In case the relationships we obtain would exhibit a similar directionality in longitudinal studies, there could be important implications for the support provided by host organizations and interventions aimed at international students. It appears that support in general is associated with positive outcomes, but making sure that support is perceived may possibly have more benefits than focusing on only the support that is enacted. This means that host institutions in higher education could not only aim at establishing support projects for international students and monitor whether these provide the services and support they envisioned—they could also carefully assess the perceptions of students of the social support. Particularly for students unfamiliar with the host environment, clear communication aimed at making available support visible could be highly important (e.g., during the welcome week, student associations, and peer groups).

We also observed that the source of the social support influenced the effect social support has on adjustment. It appears that receiving social support from multiple sources (i.e., mixed sources) is associated with the best outcomes. We also observe that support from unspecified sources was more positively related to psychological adjustment. It is unclear what unspecified support means (it could be not only mixed but also single sources). We recommend that future studies include more information to disentangle this finding.

If the effect of mixed sources is driven by having support from both conationals and hosts, this could reflect an integration strategy of both adopting the host culture by establishing new social networks and maintaining a strong cultural identity by establishing a network with conationals. Previous research posited that having both sources of social support is a stronger predictor of happiness among expatriates than having only the support of conationals or other expats (). Although this resonates with the general finding that being able to relate to two networks (host and home culture) is related to the most beneficial trajectories of acculturation (see also ), we cannot address this issue conclusively from an empirical point of view. Future studies should report effects separately so that their distinct and joint effects can be assessed.

Positive and Negative Psychological Adjustment

We find that social support is significantly associated with positive and negative psychological adjustment in the same way. This pattern is different from findings by who found that social support protects against negative outcomes, but does not boost positive outcomes. However, it is noteworthy that we are investigating international students (whereas Wang and colleagues focused on the Taiwanese general population). For international students, it might be particularly important to use social support also to boost their well-being, happiness, and have a memorable experience during their stay abroad—and not only to protect from stressors.

Limitations

We would like to acknowledge several limitations of the current study. First, sample sizes were not always large enough, and psychometric properties were not sufficient to provide clear and representative conclusions. Related to that, information is often provided in various ways. This applies to reliability coefficients, which are sometimes reported for total scales, or for a specific subscale only, across samples, as ranges with upper and lower limits, or only for specific time points in case of longitudinal designs. Especially problematic is that sources of social support (particularly from other internationals) and their effect on psychological adjustment are often reported only at the aggregate level. We recommend that future studies assess (and subsequently report) the support sources separately. This would enable future meta-analyses to disentangle the effects. The same seems to be true for the culture of origin of the international students, which could arguably represent an important moderator (; ; ; see also ). Unfortunately, samples were often mixed (40 out of 76 studies), and, thus, cultural distance to the host country could not be coded (e.g., European studies often indiscriminately included international students from European and Asian contexts).

Second, and related to that, our classification of cultural distance on the basis of which country participants come from may not reflect the cultural distance individuals perceive. We have based our distinction on the broad differences between Asian and European/North American contexts reported in the past, which relates to recent work advancing our understanding of cultural distance (see the review by ). We suggest that it is an important area for improvement to include measures of cultural distance in future studies.

Third, participants included in the study are not necessarily representative of the population of international students or receiving contexts on a global scale. The majority of the studies were conducted in the United States and 50% of the studies exclusively investigated Asian international students. Because the United States is an English-speaking country with a long history of immigration, other contexts may be less welcoming and may have steeper language barriers for international students. A very low number of European studies have been conducted, clearly highlighting the need for further investigation, particularly because of extensive student exchange programs explicitly aimed at increasing the number of international students in these countries (e.g., Erasmus exchange programs).

Fourth, we have only considered quantitative studies to provide an initial understanding of the effect sizes that were obtained. This leaves out qualitative accounts, which might provide useful insights into international students’ experiences.

Fifth, this study is based on correlational, not experimental data, challenging our inferences about causality. Although far from conclusive or necessarily ecologically valid for all contexts, there is previous work that has shown that manipulating social support in an experimental lab scenario increases indicators of health (see the meta-analysis by ). This notwithstanding, one clear avenue to prioritize in future research is to conduct longitudinal studies on groups exposed to short-term cultural influences, like international students, professionals sojourning abroad, or short-term migrants in general.

Conclusion

We provide first meta-analytic evidence that social support of all types and sources positively predicts the psychological adjustment of international students. Some types and sources of social support appear more effective for psychological adjustment: International students who subjectively feel more support, and who have support from mixed and unspecified sources have higher psychological adjustment levels. Psychological adjustment seems to generally benefit from all types and sources of social support, albeit to varying degrees, highlighting the need to differentiate between different acculturation outcomes and their anteceding conditions. It is unfortunate that we cannot further explicate the relation of unspecified sources with acculturation outcomes. We also observed much heterogeneity in terminology, scales, and sample composition, and recommend that future studies on social support adopt more comprehensive reporting to advance our understanding of social support type and sources with acculturation outcomes.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Michael Bender

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0300-5555

1. Taking the average of multiple correlations is only appropriate when the different samples are independently drawn from the same population (), which is not the case when the samples are divided by gender.

2. The average effect size for studies that reported correlations was significantly larger than that of studies reporting standardized regression coefficients β and structural equation modeling (SEM) path coefficients βsem, b = 0.17, SE = 0.045, t = −3.88, p < .001, 95% confidence interval (CI) = [−0.26, −0.086].

Supplemental Material Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Abdullah D., Aziz M. I. A., Ibrahim A. L. M. (2014). A “research” into international student-related research: (Re)Visualising our stand? Higher Education, 67, 235–253. doi:

- *Al-Sharideh K. A., Goe W. R. (1998). Ethnic communities within the university: An examination of factors influencing the personal adjustment of international students. Research in Higher Education, 39, 699–725. doi:

- Arends-Tóth J., Van de Vijver F. J. R. (2006). Issues in the conceptualization and assessment of acculturation. In Bornstein M., Cote L. (Eds.), Acculturation and parent–child relationships (pp. 33–62). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- *Atri A., Sharma M., Cottrell R. (2007). Role of social support, hardiness, and acculturation as predictors of mental health among international students of Asian Indian origin. International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 27, 59–73. doi:

- *Baba Y., Hosoda M. (2014). Home away home: Better understanding of the role of social support in predicting cross-cultural adjustment among international students. College Student Journal, 48, 1–15.

- Babiker I., Cox J., Miller P. (1980). The measurement of cultural distance and its relationship to medical consultation, symptomatology, and examination performance of overseas students of Edinburgh University. Journal of Social Psychiatry, 15, 109–116. doi:

- Barrera M. (1986). Distinctions between social support concepts, measures, and models. American Journal of Community Psychology, 14, 413–445. doi:

- *Bektaş Y., Demir A., Bowden R. (2009). Psychological adaptation of Turkish students at US campuses. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 31, 130–143. doi:

- Berry J. W. (2005). Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29, 697–712. doi:

- *Berry J. W., Kim U., Minde T., Mok D. (1987). Comparative studies of acculturative stress. International Migration Review, 21, 491–511. doi:

- Berry J. W., Poortinga Y. H., Segall M. H., Dasen P. R. (1992). Cross-cultural psychology: Research and applications. New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press.

- *Brisset C., Safdar S., Lewis J. R., Sabatier C. (2010). Psychological and sociocultural adaptation of university students in France: The case of Vietnamese international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 34, 413–426. doi:

- *Cemalcilar Z., Falbo T., Stapleton L. M. (2005). Cyber communication: A new opportunity for international students’ adaptation? International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29, 91–110. doi:

- *Charter R. A., Alexander R. A. (1993). A note on combining correlations. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 31, 123–124.

- *Chataway C. J., Berry J. W. (1989). Acculturation experiences, appraisal, coping, and adaptation: A comparison of Hong Kong Chinese, French, and English students in Canada. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 21, 295–309. doi:

- *Chen H. J., Mallinckrodt B., Mobley M. (2002). Attachment patterns of East Asian international students and sources of perceived social support as moderators of the impact of US racism and cultural distress. Asian Journal of Counselling, 9, 27–48.

- *Chirkov V. I., Safdar S., De Guzman J., Playford K. (2008). Further examining the role motivation to study abroad plays in the adaptation of international students in Canada. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 32, 427–440. doi:

- *Cho J., Yu H. (2015). Roles of university support for international students in the United States analysis of a systematic model of university identification, university support, and psychological well-being. Journal of Studies in International Education, 19, 11–27. doi:

- Chu P. S., Saucier D. A., Hafner E. (2010). Meta-analysis of the relationships between social support and well-being in children and adolescents. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29, 624–645. doi:

- Cohen J. (1977). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). New York: Academic Press.

- Cohen J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155–159. doi:

- Cohen S. (2004). Social relationships and health. American Psychologist, 59, 676–684. doi:

- Cohen S., Wills T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310–357. doi:

- de Araujo A. A. (2011). Adjustment issues of international students enrolled in American colleges and universities: A review of the literature. Higher Education Studies, 1, 624–645. doi:

- Diener E. D., Emmons R. A., Larsen R. J., Griffin S. (1985). The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. doi:

- DiMatteo M. R. (2004). Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 23, 207–218. doi:

- *Duru E., Poyrazli S. (2007). Personality dimensions, psychosocial-demographic variables, and English language competency in predicting level of acculturative stress among Turkish international students. International Journal of Stress Management, 14, 99–110. doi:

- Egger M., Smith G. D., Schneider M., Minder C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315, 629–634. doi:

- Faul F., Erdfelder E., Lang A.-G., Buchner A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. doi:

- *Furukawa T. (1997). Depressive symptoms among international exchange students, and their predictors. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 96, 242–246. doi:

- *Furukawa T., Sarason I. G., Sarason B. R. (1998). Social support and adjustment to a novel social environment. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 44, 56–70. doi:

- *Galchenko I., van de Vijver F. J. (2007). The role of perceived cultural distance in the acculturation of exchange students in Russia. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 31, 181–197. doi:

- *Geeraert N., Demoulin S. (2013). Acculturative stress or resilience? A longitudinal multilevel analysis of sojourners’ stress and self-esteem. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44, 1239–1260. doi:

- *Geeraert N., Demoulin S., Demes K. A. (2014). Choose your (international) contacts wisely: A multilevel analysis on the impact of intergroup contact while living abroad. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 38, 86–96. doi:

- *Guo Y., Li Y., Ito N. (2014). Exploring the predicted effect of social networking site use on perceived social capital and psychological well-being of Chinese international students in Japan. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17, 52–58. doi:

- Guruz K. (2011). Higher education and international student mobility in the global knowledge economy: Revised and updated (2nd ed.). New York, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Haber M. G., Cohen J. L., Lucas T., Baltes B. B. (2007). The relationship between self-reported received and perceived social support: A meta-analytic review. American Journal of Community Psychology, 39, 133–144. doi:

- Han L., Berry J. W., Zheng Y. (2016). The relationship of acculturation strategies to resilience: The moderating impact of social support among Qiang ethnicity following the 2008 Chinese earthquake. PLoS ONE, 11, e0164484. doi:

- *Hechanova-Alampay R., Beehr T. A., Christiansen N. D., Van Horn R. K. (2002). Adjustment and strain among domestic and international student sojourners a longitudinal study. School Psychology International, 23, 458–474. doi:

- *Hendrickson B., Rosen D., Aune R. K. (2011). An analysis of friendship networks, social connectedness, homesickness, and satisfaction levels of international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35, 281–295. doi:

- *Hirai R., Frazier P., Syed M. (2015). Psychological and sociocultural adjustment of first-year international students: Trajectories and predictors. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62, 438–452438. doi:

- Hupcey J. E. (1998). Social support: Assessing conceptual coherence. Qualitative Health Research, 8, 304–318. doi:

- *Hutteman R., Nestler S., Wagner J., Egloff B., Back M. D. (2015). Wherever I may roam: Processes of self-esteem development from adolescence to emerging adulthood in the context of international student exchange. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108, 767–783. doi:

- *Jackson M., Ray S., Bybell D. (2013). International students in the US: Social and psychological adjustment. Journal of International Students, 3, 17–28.

- *Jou Y. H., Fukada H. (1997). Stress and social support in mental and physical health of Chinese students in Japan. Psychological Reports, 81, 1303–1312. doi:

- *Jung E., Hecht M. L., Wadsworth B. C. (2007). The role of identity in international students’ psychological well-being in the United States: A model of depression level, identity gaps, discrimination, and acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 31, 605–624. doi:

- Kaczmarek P. G., Matlock G., Merta R., Ames M. H., Ross M. (1994). An assessment of international college student adjustment. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 17, 241–247. doi:

- Kaplan B. H., Cassel J. C., Gore S. (1977). Social support and health. Medical Care, 15, 47–58. doi:

- *Kashima E. S., Loh E. (2006). International students’ acculturation: Effects of international, conational, and local ties and need for closure. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30, 471–485. doi:

- *Khawaja N. G., Dempsey J. (2007). Psychological distress in international university students: An Australian study. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 17, 13–27. doi:

- Kossek E. E., Pichler S., Bodner T., Hammer L. B. (2011). Workplace social support and work–family conflict: A meta-analysis clarifying the influence of general and work–family-specific supervisor and organizational support. Personnel Psychology, 64, 289–313. doi:

- *Lee J. S., Koeske G. F., Sales E. (2004). Social support buffering of acculturative stress: A study of mental health symptoms among Korean international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 28, 399–414. doi:

- Lee R. M., Robbins S. B. (1995). Measuring belongingness: The social connectedness and the social assurance scales. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42, 232–241. doi:

- *Lian Z. (2017). Predictors of depression/anxiety, mental health service utilization, and help-seeking for Chinese international students: The role of acculturation, microaggressions, social support, coping self-efficacy, stigma, and college staffs’ cultural competence and cultural humility (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Teachers College, Columbia University, New York City, NY.

- Lin J. H., Peng W., Kim M., Kim S. Y., LaRose R. (2012). Social networking and adjustments among international students. New Media & Society, 14, 421–440. doi:

- Luszczynska A., Sarkar Y., Knoll N. (2007). Received social support, self-efficacy, and finding benefits in disease as predictors of physical functioning and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Patient Education and Counseling, 66, 37–42. doi:

- *Mak A. S., Bodycott P., Ramburuth P. (2015). Beyond host language proficiency: Coping resources predicting international students’ satisfaction. Journal of Studies in International Education, 19, 460–475. doi:

- *Mak A. S., Kim I. (2011). Korean international students’ coping resources and psychological adjustment in Australia. OMNES: The Journal of Multicultural Society, 2, 56–84. doi:

- *Mallinckrodt B., Leong F. T. (1992). International graduate students, stress, and social support. Journal of College Student Development, 33, 71–78.

- Maundeni T. (2001). The role of social networks in the adjustment of African students to British society: Students’ perceptions. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 4, 253–276. doi:

- *Meghani D. T., Harvey E. A. (2016). Asian Indian international students’ trajectories of depression, acculturation, and enculturation. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 7, 1–14. doi:

- *Misra R., Crist M., Burant C. J. (2003). Relationships among life stress, social support, academic stressors, and reactions to stressors of international students in the United States. International Journal of Stress Management, 10, 137–157. doi:

- Mori S. C. (2000). Addressing the mental health concerns of international students. Journal of Counseling & Development, 78, 137–144. doi:

- Moeyaert M., Ugille M., Natasha Beretvas S., Ferron J., Bunuan R., Van den Noortgate W. (2017). Methods for dealing with multiple outcomes in meta-analysis : a comparison between averaging effect sizes, robust variance estimation and multilevel meta-analysis. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20, 559–572. doi:

- Muthukrishna M., Bell A., Henrich J., Curtin C., Gedranovich A., McInerney J., Thue B. (2018). Beyond WEIRD psychology: Measuring and mapping scales of cultural and psychological distance. SSRN Electronic Journal. Advance online publication. doi:

- *Ng T. K., Tsang K. K., Lian Y. (2013). Acculturation strategies, social support, and cross-cultural adaptation: A mediation analysis. Asia Pacific Education Review, 14, 593–601. doi:

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2015). Education at a glance 2015: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- *Olaniran B. A. (1993). International students’ network patterns and cultural stress: What really counts. Communication Research Reports, 10, 69–83. doi:

- *Ozer S. (2015). Predictors of international students’ psychological and sociocultural adjustment to the context of reception while studying at Aarhus University, Denmark. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 56, 717–725. doi:

- *Pan J. Y., Wong D. F. K. (2011). Acculturative stressors and acculturative strategies as predictors of negative affect among Chinese international students in Australia and Hong Kong: A cross-cultural comparative study. Academic Psychiatry, 35, 376–381. doi:

- *Pan J. Y., Wong D. F. K., Joubert L., Chan C. L. W. (2007). Acculturative stressor and meaning of life as predictors of negative affect in acculturation: A cross-cultural comparative study between Chinese international students in Australia and Hong Kong. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 41, 740–750. doi:

- *Park N., Noh H. (2018). Effects of mobile instant messenger use on acculturative stress among international students in South Korea. Computers in Human Behavior, 82, 34–43. doi:

- *Park N., Song H., Lee K. M. (2014). Social networking sites and other media use, acculturation stress, and psychological well-being among East Asian college students in the United States. Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 138–146. doi:

- *Perrucci R., Hu H. (1995). Satisfaction with social and educational experiences among international graduate students. Research in Higher Education, 36, 491–508. doi:

- Peterson R. A., Brown S. P. (2005). On the use of beta coefficients in meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 175–181. doi:

- *Poyrazli S., Kavanaugh P. R., Baker A., Al-Timimi N. (2004). Social support and demographic correlates of acculturative stress in international students. Journal of College Counseling, 7, 73–83. doi:

- Prati G., Pietrantoni L. (2009). Optimism, social support, and coping strategies as factors contributing to posttraumatic growth: A meta-analysis. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 14, 364–388. doi:

- Prati G., Pietrantoni L. (2010). The relation of perceived and received social support to mental health among first responders: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Community Psychology, 38, 403–417. doi:

- *Ra Y.-A. (2016). Social support and acculturative stress among Korean international students. Journal of College Student Development, 57, 885–891. doi:

- *Ra Y.-A., Trusty J. (2017). Impact of social support and coping on acculturation and acculturative stress of East Asian international students. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 45, 276–291. doi:

- Radloff L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. doi:

- *Ramos M. R., Cassidy C., Reicher S., Haslam S. A. (2015). Well-being in cross-cultural transitions: Discrepancies between acculturation preferences and actual intergroup and intragroup contact. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 45, 23–34. doi:

- R Core Team. (2018). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org

- Reinhardt J. P., Boerner K., Horowitz A. (2006). Good to have but not to use: Differential impact of perceived and received support on well-being. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 23, 117–129. doi:

- Rosenberg M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. doi:

- *Rui J. R., Wang H. (2015). Social network sites and international students’ cross-cultural adaptation. Computers in Human Behavior, 49, 400–411. doi:

- *Sam D. L. (2001). Satisfaction with life among international students: An exploratory study. Social Indicators Research, 53, 315–337. doi:

- *Sam D. L., Tetteh D. K., Amponsah B. (2015). Satisfaction with life and psychological symptoms among international students in Ghana and their correlates. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 49, 156–167. doi:

- Sandhu D. S., Asrabadi B. R. (1994). Development of an Acculturative Stress Scale for International Students: Preliminary findings. Psychological Reports, 75, 435–448. doi:

- Sarason I. G., Sarason B. R. (2009). Social support: Mapping the construct. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 26, 113–120. doi:

- Schwarzer R., Leppin A. (1989). Social support and health: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Health, 3, 1–15. doi:

- *Searle W., Ward C. (1990). The prediction of psychological and sociocultural adjustment during cross-cultural transitions. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 14, 449–464. doi:

- *Seo H., Harn R.-W., Ebrahim H., Aldana J. (2016). International students’ social media use and social adjustment. First Monday, 21(11), 11–17.

- *Shafaei A., Razak N. A. (2016). International postgraduate students’ cross-cultural adaptation in Malaysia: Antecedents and outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 57, 739–767. doi:

- Smith R. A., Khawaja N. G. (2011). A review of the acculturation experiences of international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35, 699–713. doi:

- Solomon Z., Mikulincer M., Hobfoll S. E. (1987). Objective versus subjective measurement of stress and social support: Combat-related reactions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55, 577–583. doi:

- Stern J. A. C., Egger M. (2005). Regression methods to detect publication and other bias in meta-analysis. In Rothstein H., Sutton A. J., Borenstein M. (Eds.), Publication bias in meta analysis: Prevention, assessment and adjustments (pp. 99–110). Chichester, England: Wiley.

- *Sullivan C., Kashubeck-West S. (2015). The interplay of international students’ acculturative stress, social support, and acculturation modes. Journal of International Students, 5, 1–11.

- *Sümer S., Poyrazli S., Grahame K. (2008). Predictors of depression and anxiety among international students. Journal of Counseling and Development, 86, 429–437. doi:

- *Thomson G., Rosenthal D., Russell J. (2006). Cultural stress among international students at an Australian university In Proceedings of Australian international education conference (pp. 1–8). Perth, Australia. Retrieved from http://aiec.idp.com/uploads/pdf/Thomson%20%28Paper%29%20Fri%201050%20MR5.pdf

- Thorsteinsson E. B., James J. E. (1999). A meta-analysis of the effects of experimental manipulations of social support during laboratory stress. Psychology and Health, 14, 869–886. doi:

- Torbiörn I. (1982). Living abroad: Personal adjustment and personnel policy in the overseas setting. New York, NY: John Wiley.

- *Tsai W., Wang K. T., Wei M. (2017). Reciprocal relations between social self-efficacy and loneliness among Chinese international students. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 8, 94–102. doi:

- UNESCO Institute of Statistics. (2010). Global education digest 2010: Comparing education statistics across the world. Montreal, Quebec, Canada: Author.

- Van Osch Y. M. J., Breugelmans S. M. (2012). Perceived intergroup difference as an organizing principle of intercultural attitudes and acculturation attitudes. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 43, 801–821. doi:

- Vaux A., Riedel S., Stewart D. (1987). Modes of social support: The social support behaviors (SS-B) scale. American Journal of Community Psychology, 15, 209–232. doi:

- Viechtbauer W. (2010). Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software, 36, 1–48. doi:

- Viswesvaran C., Sanchez J. I., Fisher J. (1999). The role of social support in the process of work stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54, 314–334. doi:

- Wang H. H., Wu S. Z., Liu Y. Y. (2003). Association between social support and health outcomes: A meta-analysis. The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 19, 345–350. doi:

- *Wang J., Hong J. Z., Pi Z. L. (2015). Cross-cultural adaptation: The impact of online social support and the role of gender. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 43, 111–121.

- *Wang K. T., Wei M., Chen H. H. (2015). Social factors in cross-national adjustment subjective well-being trajectories among Chinese international students. The Counseling Psychologist, 43, 272–298. doi:

- *Wang L., Wang K. T., Heppner P. P., Chuang C.-C. (2017). Cross-national cultural competency among Taiwanese international students. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 10, 271–287. doi:

- Wang Y., Xiao F. (2014). East Asian international students and psychological well-being: A systematic review. Journal of International Students, 4, 301–313.

- Ward C., Searle W. (1991). The impact of value discrepancies and cultural identity on psychological and sociocultural adjustment of sojourners. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 15, 209–224. doi:

- Wei M., Ku T. Y., Russell D. W., Mallinckrodt B., Liao K. Y. H. (2008). Moderating effects of three coping strategies and self-esteem on perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms: A minority stress model for Asian international students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55, 451–462451. doi:

- *Wei M., Liang Y. S., Du Y., Botello R., Li C. I. (2015). Moderating effects of perceived language discrimination on mental health outcomes among Chinese international students. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 6, 213–222. doi:

- *Yang B., Clum G. A. (1995). Measures of life stress and social support specific to an Asian student population. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 17, 51–67. doi:

- *Ye J. (2006a). An examination of acculturative stress, interpersonal social support, and use of online ethnic social groups among Chinese international students. The Howard Journal of Communications, 17, 1–20. doi:

- *Ye J. (2006b). Traditional and online support networks in the cross-cultural adaptation of Chinese international students in the United States. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11, 863–876. doi:

- *Yeh C. J., Inose M. (2003). International students’ reported English fluency, social support satisfaction, and social connectedness as predictors of acculturative stress. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 16, 15–28. doi:

- *Ying Y. W. (2005). Variation in acculturative stressors over time: A study of Taiwanese students in the United States. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29, 59–71. doi:

- *Ying Y. W., Han M. (2006). The contribution of personality, acculturative stressors, and social affiliation to adjustment: A longitudinal study of Taiwanese students in the United States. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30, 623–635. doi:

- *Ying Y. W., Liese L. H. (1990). Initial adaptation of Taiwan foreign students to the United States: The impact of prearrival variables. American Journal of Community Psychology, 18, 825–845. doi:

- *Young T. J., Sercombe P. G., Sachdev I., Naeb R., Schartner A. (2013). Success factors for international postgraduate students’ adjustment: Exploring the roles of intercultural competence, language proficiency, social contact and social support. European Journal of Higher Education, 3, 151–171. doi:

- *Yusliza M. Y. (2011). Self-efficacy, perceived social support, and psychological adjustment in international undergraduate students in a public higher education institution in Malaysia. Journal of Studies in International Education, 16, 353–371. doi:

- *Yusliza M. Y., Abdul Kadir O. (2011). An early study on perceived social support and psychological adjustment among international students: The case of a higher learning institution in Malaysia. International Journal of Business and Society, 12, 1–15.

- *Zhang J., Goodson P. (2011). Acculturation and psychosocial adjustment of Chinese international students: Examining mediation and moderation effects. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35, 614–627. doi:

- Zhang J., Goodson P. (2011). Predictors of international students’ psychosocial adjustment to life in the United States: A systematic review. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35, 139–162. doi:

- Zimet G. D., Dahlem N. W., Zimet S. G., Farley G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52, 30–41. doi:

*References marked with an asterisk indicate studies that are included in the meta-analysis.