Positive thinking has long fascinated the public (e.g., ; ). This makes sense given that thinking positively has been associated with a variety of favorable life outcomes (; , ). Past research often compares positive thinking or optimism across cultures while focusing on culture main effects (; ; ; ), with minimal attention on the influence of context. To fill the gap, this paper examines how contextual factors (i.e., positive vs. negative events) may moderate cross-cultural differences in positive thinking.

We define positive thinking as the tendency to have a preponderance of positive (pleasant, favorable) thoughts relative to negative (unpleasant, unfavorable) thoughts. Positive thinking may emerge because people consider both positive and negative thoughts, but their thought processes favor positive over negative thoughts (e.g., having but dismissing negative thoughts), or because people generate more positive than negative thoughts in the first place. Similarly, positive thinking can reference any subject or timeframe. For example, optimism and pessimism may be considered specific instances of positive (versus negative) thinking that reference oneself in the future (; ; ). Similarly, , ) work specifically addresses overly positive self-relevant thoughts (“positive illusions”). However, positive thinking is just a preponderance of thoughts of positive versus negative valence, and the construct need not be constrained to first-person, future-oriented thoughts. Positive thinking can also be captured in thoughts about other people or about outcomes very broadly (e.g., thoughts about the fate of humanity) and thoughts about the past or the present. In this work, we focus on future timeframes because the future is inherently ambiguous, creating a lot of variance in responses. However, our studies consider both thoughts about the self and impersonal contexts to ensure generalizability of our claims.

Cultural Variation in Positive Thinking

Broadly speaking, most research has indicated that people from Western cultures strongly prefer positivity in many aspects of their experiences, whereas people from Eastern cultures have a more mixed set of preferences. Most research treats these preferences or tendencies for increased Western positivity as fixed (dispositional) differences in underlying traits. For example, compared to Americans, Chinese are less optimistic (but see ; ), and/or more pessimistic (; ; ). Relatedly, Japanese show less unrealistic optimism than Canadians (). Euro-Americans and Euro-Canadians (i.e., North Americans of European ancestry) expend more effort than Asian-Americans and Asian-Canadians (i.e., North Americans of Asian ancestry) to experience positive feedback and enjoyment and avoid tasks that give negative feedback (; ). Furthermore, Asian-Canadians focus more on negative social comparison information (i.e., negative role models); whereas European-Canadians focus primarily on positive social comparison targets (). Finally, life satisfaction is less closely linked to a dense association of positive constructs among Koreans and Asian-Americans versus Euro-Americans (). Thus, East Asians may have weaker inclinations for positive thinking relative to Western people.

Various explanations have been used to explain these cultural differences. A highly influential theory implicates self-enhancement. Eastern individuals, motivated to self-improve, may show less positive thinking at least about themselves; Western individuals are motivated to self-enhance, thus they tend to think more positively about themselves (; ). In addition, cultural differences in values such as uncertainty avoidance, individualism, and/or power distance (), may account for cultural variance in positive thinking (; ; ). For example, Chinese people might engage in less positive thinking due to their higher uncertainty avoidance: “by anticipating the worst, some Asians may paradoxically gain a sense of control in their uncertainty about future outcomes” (, p. 821). These perspectives suggest stable cultural differences in positive thinking by pointing to cultural values that should remain intact regardless of context. However, a purely “fixed cultural difference” perspective has some issues. For instance, one recent meta-analysis () offers no support for overall cultural differences in optimism among mainland Chinese, Canadians, and Americans. This null effect suggests that cultural differences in positive thinking may be variable across context.

Relatedly, most research tends to characterize optimism, which we classify as a specific type of positive thinking, as a fixed trait (; ; ; ). However, optimism can be situationally determined. For example, people may be less optimistic when anticipating feedback (vs. not), when outcomes are important (vs. unimportant), when negative outcomes are more accessible (vs. less accessible), when outcomes are uncontrollable (vs. controllable), and when they have low (vs. high) self-esteem (). Positive thinking more generally may also be situationally determined.

Fluctuating contextual factors may be responsible for the inconsistency in previous findings on optimism. Although optimism has been treated as a trait in most research, it can change over time in response to novel information (but see ; ; ). This opens the door to situational pressures being able to shift how positively people think about the future. We propose that seemingly cross-cultural differences in positive thinking—often assumed to be fixed—may actually appear, disappear, or reverse depending on situational factors. In the present research, we examine one such contextual variable: the valence of the context or events to which people are responding.

Culture, Cognition, and Positive Thinking in Context

Culture shapes people’s thinking style and beliefs (). have demonstrated a tendency for different thinking styles between East Asians and Westerners (i.e., people of European descents). Specifically, Westerners tend to think analytically, attending primarily to an object and the categories it belongs to, and using rules including formal logic to understand its behaviors. In contrast, East Asians tend to think holistically, attending to the field and context, making less use of categories and formal logic, and relying on dialectical reasoning (i.e., tolerating and accepting contradictions; ). For instance, Chinese are more likely to believe in a form of dialecticism whereby opposing statements are resolved by finding a “middle way” or accepting contradictions. In contrast, Americans think in an Aristotelian manner: when information conflicts, Americans seek to determine which is true and which is false, henceforth endorsing only the true proposition ().

Interestingly, these beliefs can help account for cross-cultural differences. For example, found that higher ambivalence in the experience of positive and negative self-relevant thoughts (among Asian-Americans versus European-Americans) were mediated by “naive dialecticism in the domain of self-perception” (p. 1423). Similarly, showed that higher rates of simultaneous positive and negative emotion (among Chinese versus Americans) depended on dialectical thinking. Underlying lay beliefs may also help to explain cultural differences in positive and negative thinking.

One important principle underlying Chinese dialectical thinking is their belief in change (). Chinese tend to hold stronger beliefs in change, especially cyclical change, compared to North Americans (; ). If events and people are constantly changing, then contradiction becomes inevitable. Thus, believing in constant change may lead people to accept contradictions. have shown that Chinese and Americans hold different lay theories of change—beliefs about how events develop over time (; also see ; ). Chinese are more likely than North Americans to believe that the world is constantly and cyclically changing (e.g., what goes up will come down, and what comes down will go up), with this gap developing as early as middle childhood (). For example, Chinese participants were more likely than North Americans to expect two people fighting currently to become lovers one day and to expect a dating couple to break up after graduating from university (). Likewise, Chinese were more likely to view personal happiness and unhappiness to transform into each other (because life is expected to change), whereas Americans tended to see happiness as something stable (because life is expected not to change; ). Interestingly, Koreans are also more likely than Americans to anticipate changes in future events, consistent with the prediction that holistic (vs. analytic) cultures will be more likely to anticipate change ().

Cultural differences in lay theories of change, therefore, suggest that Chinese are more likely than North Americans to expect good and bad events to convert into each other. Due to such differences in lay theories of change, one would expect cultural differences in positive thinking, at least about the future, to vary depending on the context. In response to positive events, Chinese may have more negative (less positive) thoughts about the future than do North Americans; in response to negative events, Chinese may have more positive (less negative) thoughts than do North Americans.

Existing evidence partially backs up this reasoning. In response to real life negative events such as the SARS outbreak or the COVID-19 pandemic, Chinese participants were more likely than Euro-Canadians to mention positive changes brought to their life and the world by the negative event (; ). These findings appear at odds with some previous findings that Chinese engage in less positive thinking than North Americans. We argue that the context may explain the contrasting findings. In response to positive events, Chinese may engage in less positive thinking (i.e., will expect bad outcomes to arise from good events) than North Americans do. But in response to negative events (like SARS), Chinese may show more positive thinking (i.e., will expect good outcomes to arise from bad events) than North Americans do.

The Present Work

The present research focuses on a contextual factor (i.e., positive vs. negative events) as a moderator of cross-cultural differences in positive thinking. As we derive our predictions based on past research involving East Asian (including Chinese, Japanese and Koreans) and European Americans or Canadian samples, the present research compares an East Asian group (i.e., Chinese) with Euro-Canadians. Based on previous research on cultural differences in dialectical thinking and especially lay theories of change, we predicted that cultural differences in endorsing positive thinking should be qualified by context. Specifically, compared to Euro-Canadians, Chinese participants should endorse less positive thinking about the future in positive contexts and more positive thinking in negative contexts. Furthermore, such an effect may be accounted for by Chinese people’s (vs. Euro-Canadians’) greater belief in change.

We conducted three studies to test the predictions. In each study, we provided Chinese and Euro-Canadian participants with either positive and/or negative hypothetical events and then assessed the positivity of their thinking. In all studies, pilot testing determined that both cultural groups recognized the positive (negative) events as positive (negative), supporting that differences here indicate distinctions in the groups’ thinking processes about events rather than initial judgment of events themselves. Study 1 presented participants with both positive and negative events, in response to which participants rated the perceived likelihood of given positive and negative thinking responses. Study 2 replicated Study 1 without using rating scales. Study 3 asked participants to generate their own outcomes for positive and negative events, another approach to measure positive and negative thinking. In addition, Study 3 investigated the underlying mechanism for cultural differences in positive (or negative) thinking in context, namely, lay theories of change.

Study 1

In Study 1, participants read about several events, half of which were positive, and the other half negative. Participants indicated their endorsements of responses reflecting positive and negative thinking. The study had a 2 (Culture: Chinese vs. Euro-Canadian) × 2 (Context: positive vs. negative event) × 2 (Response: positive vs. negative thinking) mixed design, with the latter two variables as within-participant factors. We hypothesized that Chinese, compared to Euro-Canadians, would show less positive thinking in response to positive events but more positive thinking in response to negative events.

Method

Participants

One hundred and forty-five Chinese undergraduate students in China (56 women; Mage = 21.7, SDage = 3.1) and 142 Euro-Canadian undergraduate students (73 women; Mage = 19.8, SDage = 1.3) in Canada participated. Our stopping rule was to collect data until the end of a semester, and a sensitivity analysis using G*Power () shows we had 80% power to find small effects (d ≥ 0.138, η2 ≥ 0 .005) given our repeated-measure design. Chinese participants were significantly older than Euro-Canadians, t(236) = 6.45, p < .001, d = 0.82 [0.56, 1.09], but including age as a covariate did not change our results.

Materials and procedure

Participants read two positive and two negative events and imagined themselves experiencing them. Based on a pretest, the positive events were considered as positive by both Chinese (n = 78) and Euro-Canadians (n = 52), and the negative events were considered as negative by both groups (one-sample t tests for each stimulus compared against 0, calculated separately for Chinese and Euro-Canadians; ts > |7.39|, ps < 0.001, ds > |1.03|). Furthermore, the two culture groups in the pretest did not differ in their ratings of each event, Fs (1, 128) < 1.70, ps > 0.19. The positive events were, “You have won the last two photography contests in university,” and “You asked someone you like to go to a movie, and he/she agreed.” The negative events were “You lost the last two photography contests in university,” and “You asked someone you like to go to a movie, but he/she turned you down.” For each event, we provided responses that were seen as positive and negative by Chinese and Euro-Canadians in a pretest. For example, “You have won the last two photography contests in university” was followed by “Past success boosts my confidence, which will help me win the next contest” (positive thinking) and “Past success puts a lot of pressure on me, which will hinder my performance in the next contest” (negative thinking). Participants imagined themselves experiencing the events and indicated their endorsement of each response from −5 (Completely Disagree) to +5 (Completely Agree). The order of positive and negative responses was counterbalanced. Materials were translated into Chinese and checked by bilingual researchers for equivalence of meaning.

Results and Discussion

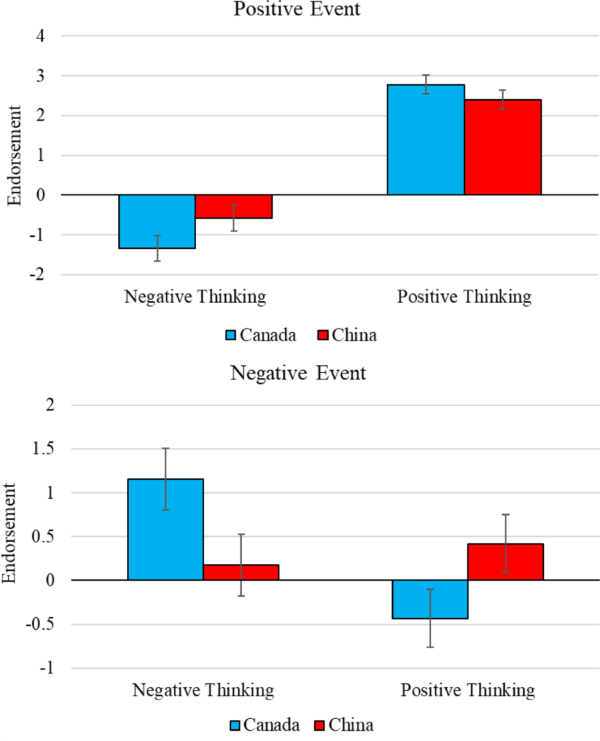

We conducted a 2 (Culture: Chinese vs Euro-Canadian) × 2 (Event Valence: positive vs. negative) × 2 (Response: positive vs. negative thinking) ANOVA with the latter two variables as within-participant variables. The key three-way interaction was significant, F(1, 285) = 34.85, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.11. As shown in Figure 1, for positive events, the two-way interaction between culture and response was significant, F(1, 285) = 11.24, p = .001, ηp2 = 0.04. Chinese endorsed less positive thinking, F(1, 285) = 4.92, p = .027, ηp2 = 0.02, and more negative thinking, F(1, 285) = 10.55, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.04, than did Euro-Canadians.

Figure 1

Chinese and Euro-Canadian endorsements with positive and negative thinking for positive and negative events. (Study 1.)

Note. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

The opposite pattern was found for negative events, where once again the two-way interaction between culture and response was significant, F(1, 285) = 18.53, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.06. When given negative events, Chinese endorsed positive thinking more, F(1, 285) = 12.64, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.042, and negative thinking less, F(1, 285) = 15.08, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.050, than Euro-Canadians did. Thus, supporting our hypothesis, compared to Euro-Canadians, Chinese showed less positive thinking given positive events and more positive thinking given negative events. We also found main effects of event valence and response, and two-way interactions between event valence and culture as well as between event valence and response, Fs(1, 285) > 3.99, ps < 0.05.

Study 2

In Study 2, we conceptually replicated Study 1. Instead of using continuous rating scales, participants made binary choices reflective of positive or negative thinking. This choice approach minimizes concerns regarding potential cultural differences in extreme response bias (e.g., ). For example, some readers might wonder if the effects in Figure 1 were driven by Chinese endorsing less extreme responses (but see ). Such a criticism would not explain a binary-judgment in which gradations of “extreme” response do not exist. The study followed a 2 (Culture) × 2 (Context: positive vs. negative event) between-participant design.

Method

Participants

Chinese undergraduate students in China (N = 120, n = 60 women) and 125 Euro-Canadian undergraduate students (96 women) in Canada participated. According to a sensitivity analysis, we had 80% power to find small-medium effects (d ≥ 0.360, η2 ≥ 0.031).

Materials and procedure

Participants read about either a positive or a negative event. In all cases, the event involved approaching a potential romantic partner. In the negative event valence condition, participants read, “You asked someone you like to go to a movie, but he/she turned you down.” In the positive event valence condition, participants read, “You asked someone you like to go to a movie, and he/she agreed.” For either event, participants had to select one of two responses: one positive, and one negative. For example, in the positive condition, the positive response was “He/She probably likes me and will go out with me again,” and the negative thought was “He/She was probably just being polite and will not go out with me again.” Next, we measured participants’ mood as a potential covariate. Participants rated (0 = Not at All to 6 = Very Strongly) how much they felt positively and negatively. The study was conducted as part of a larger package with other unrelated studies.

Results

Positive thinking

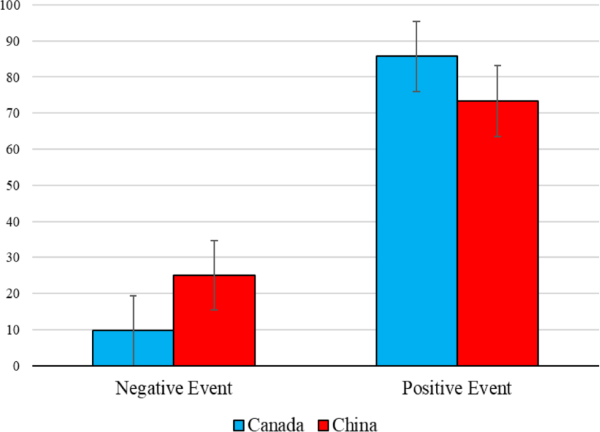

For our primary analysis, we conducted binomial logistic regression in R (). Choice of negative thoughts (scored 0) versus positive thoughts (scored 1), the dependent variable, was regressed onto Culture (Chinese = +0.5, Euro-Canadian = −0.5), Event Valence (Positive = +0.5, Negative = −0.5), and their interaction term. The critical interaction of Culture X Event Valence was significant, B = −2.02, Z = −2.73, p = .006, OR = 0.13 [0.03, 0.55], as depicted in Figure 2. In the positive event condition, fewer Chinese (M = 73.3%, SD = 44.6%) than Euro-Canadians (M = 85.7%, SD = 35.3%) endorsed positive thinking, although this difference was non-significant, B = −0.78, Z = −1.68, p = .092, OR = 0.46 [0.18, 1.12]. In the negative event condition, significantly more Chinese (M = 25.0%, SD = 43.7%) endorsed positive thinking than did Euro-Canadians (M = 9.7%, SD = 29.8%), B = 1.14, Z = 2.17, p = .030, OR = 3.11 [1.16, 9.32]. Critically, however, the interaction effect means that the group differences differed significantly as a function of event type (positive versus negative). Additionally, a simple effect of condition, B = 3.07, Z = 8.78, p < .001, OR = 21.49, CI95% = [11.14, 44.12] revealed, unsurprisingly, that more positive thoughts were chosen in the positive (M = 79.5%, SD = 38.9%) than in the negative (M = 17.3%, SD = 38.9%) condition.

Figure 2

Percentage of Chinese and Euro-Canadian participants endorsing positive thought in Study 2.

Note. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

Overall, Chinese thought more positively in a negative context and thought slightly more negatively in a positive context, compared to Euro-Canadians. Thus, with a binary choice task, Study 2 replicated Study 1’s results, revealing that cultural differences in positive thinking actually depend on context. Importantly, these findings undermine the potential criticism that Study 1’s effects were driven by cultural differences in extreme responding.

Study 3

In Study 3, we moved to an open thought-listing/rating task whereby Chinese and Euro-Canadian participants generated their own ideas about how certain events would unfold. We predicted that Chinese would be more likely than Euro-Canadians to generate negative outcomes for positive events and to generate positive outcomes for negative events. Furthermore, we hypothesized that these differences would be accounted for by lay theories of change. The study had a 2 (Culture) × 2 (Context: positive vs. negative event) design, with Context as a within participant factor.

Method

Pretest

To find positive and negative events that would be considered equally positive or negative by Chinese and Canadian participants, we had a group of university students in China (n = 197) and Canada (n = 145) read events considered applicable in both China and Canada, and then they rated how positive/negative they believed each of the events was, using a scale ranging from −5 (Extremely Negative) to +5 (Extremely Positive). Of 183 events, 34 events (19%) showed minimal cross-group differences (ps > 0.20). From these 34 events, three positive and three negative events were selected on the basis of positive/negative events being similar in terms of absolute magnitude (positive events: +3.40 to +3.96; negative events: −3.43 to −4.02).

Participants

Three-hundred and thirty-three Chinese undergraduates in China (118 women; Mage = 18.3, SDage = 0.8) and 240 Euro-Canadian undergraduate students in Canada (189 women; Mage = 18.2, SDage = 1.1) participated. All effects remained intact when controlling for gender. This sample size provides over 80% power to detect an indirect effect even if both mediation pathways are small (see ). We decided on this large sample size so that Study 3 could provide a powerful final demonstration of our key effects.

Materials and procedure

Participants read three positive events (a person winning a public speaking contest, a person getting an ideal job after a tight competition, and a person having a surprise birthday party thrown by a friend) and three negative events (a person finding out they have lung cancer, a person getting mugged, and a person losing all the money in a stock investment). For each event, participants were to list thoughts about outcomes that would plausibly follow (maximum 10). Then for each thought they generated, participants rated how positive/negative it was on a scale from −5 (Extremely Negative) to +5 (Extremely Positive). This item was used to assess participants’ positive thinking.

Afterward, participants completed 11 items measuring their lay theories of change (LTC), ranging on a scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree) with higher scores representing stronger belief in cyclical change. Sample item: “A rich person is likely to become poor, and a poor person is likely to become rich.” Finally, participants reported their gender, age, and ethnicity.

Results and Discussion

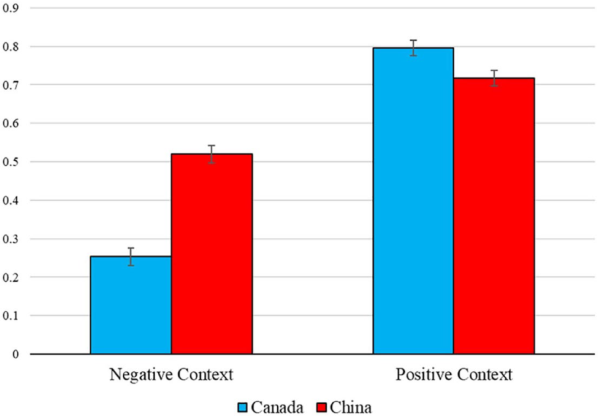

Positive thinking: Proportion of positive thoughts

On average, Chinese (M = 4.46, SD = 1.71) generated fewer outcomes per event than Euro-Canadians did (M = 5.72, SD = 1.88), t(571) = −8.39, p < .001, d = 0.71 [0.54, 0.88]. Therefore, for each event, we created a proportional measure by dividing the number of all positive outcomes listed (i.e., outcomes rated +1 to +5) by the sum of all negative (i.e., outcomes rated −1 to −5) and positive outcomes combined. We then averaged this proportion index across the three positive events and across the three negative events, respectively. On this proportion measure (ranging between 0 and 1), scores over 0.5 indicate positive thinking (generating a greater number of positive than negative outcomes), and numbers under 0.5 indicate negative thinking (generating a greater number of negative than positive outcomes).

A 2 (Culture: Chinese vs Euro-Canadian) × 2 (Event Valence: positive or negative) mixed ANOVA on positive thinking revealed a significant interaction, F(1, 569) = 261.50, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.32. As Figure 3a shows, for positive events, although both cultural groups showed significant positive thinking, Chinese thought less positively (M = 0.72, SD = 0.20) than did Euro-Canadians (M = 0.80, SD = 0.17), Mdiff = −0.08 [−0.11, −0.05], p < .001. In contrast, for negative events, Chinese thought more positively (M = 0.52, SD = 0.18) than did Euro-Canadians (M = 0.25, SD = 0.19), Mdiff = 0.27 [0.24, 0.30], p < .001. These results support our hypothesis. This analysis also revealed a significant main effect of culture, F(1, 569) = 68.59, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.11 and a significant main effect of event valence, F(1, 569) = 1197.94, p < .001, ηp2 = .68.

Figure 3a

Positive thinking (thought proportion) generated in response to positive and negative events (Study 3).

Note. Error bars refer to 95% confidence intervals.

Positive thinking: Valence of thoughts

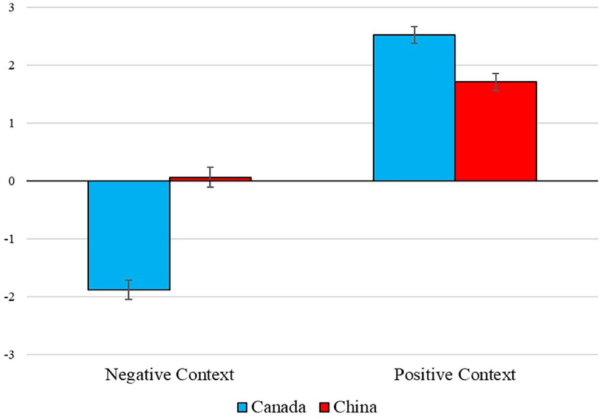

We predicted that the outcomes associated with positive events should be less positive for Chinese than for Euro-Canadians, and the outcomes associated with negative events should be less negative for Chinese than for Euro-Canadians. A 2 (Culture) × 2 (Event Valence) mixed ANOVA on participants’ ratings of the self-generated outcomes, averaged across events, revealed a significant interaction, F(1, 571) = 308.90, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.351.

As Figure 3b reveals, Chinese thought less positively (M = 1.71, SD = 1.47) than did Euro-Canadians (M = 2.53, SD = 1.27) for positive events, Mdiff = −0.82 [−1.05, −0.59], p < .001. Furthermore, Chinese thought less negatively (M = 0.07, SD = 1.27) than did Euro-Canadians (M = −1.88, SD = 1.39) for negative events, Mdiff = 1.94 [1.72, 2.16], p = .001. This pattern conceptually replicates the previous analysis, as well as Studies 1-2, but substitutes a free thought-listing task. Thus, cross-cultural differences emerged when positivity/negativity were not even mentioned until after thoughts were already generated. In addition, we identified a significant main effect of culture, F(1, 214) = 6.92, p = .009, ηp2 = 0.03, and a significant main effect of event valence, F(1, 214) = 742.71, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.67.

Figure 3b

Positive thinking (average valence) generated in response to positive and negative events.

Note. Error bars refer to 95% confidence intervals.

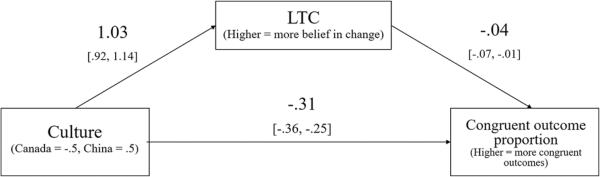

Mediation: Lay theory of change (LTC)

We established the LTC’s factor structure by separately examining Chinese and Euro-Canadian data with respect to scree plots, fit indices (SRMR, RMSEA), and interpretability of resulting solutions, detailed in Supplementary-2. Chinese endorsed greater lay theories of change (M = 2.83, SD = 0.64, α = 0.62) than did Euro-Canadians (M = 1.80, SD = 0.69, α = 0.72), t(570) = 18.42, p < .0001, d = 1.56 [1.37, 1.75]. To investigate if lay theories of change accounted for cultural differences in positive thinking, we conducted mediation analyses. Although mediation analysis cannot prove a causal order given our partially cross-sectional design (), it can reveal if the data pattern is consistent with a mechanistic interpretation. Because regression requires a single outcome score, we created difference scores for our two dependent variables as noted below.

We subtracted the proportion of positive thoughts generated for negative events from positive thoughts generated for positive events to create an index representing relatively positive thoughts in relatively positive contexts. This index represented the tendency to engage in thinking whose valence matches the context (i.e., positive thinking in a positive context, negative thinking in a negative context), so we labeled it congruent outcome expectancy. Alternatively, low scores can be understood as “expected change” from the event to the outcome.

To test if culture influenced congruent outcome expectancy via differences in LTC, we ran Model 4 (simple mediation) in Process 3.3 with SPSS (). As seen in Figure 4, culture predicted LTC, B = 1.03 [0.92, 1.14], t(568) = 18.58, p < .001, and LTC predicted congruent outcome expectancy, B = −0.04 [−0.07, −0.01], t(567) = −2.38, p = .017. A 95% percentile-based bootstrapped confidence interval based on 10,000 bootstrap samples was entirely below zero [−0.08, −0.01], indicating a significant indirect effect of culture on congruent outcome expectancy through lay theories of change. Thus, Chinese people’s increased tendency to believe in the lay theory of change partially accounted for their weaker tendency for positive thinking in positive contexts and negative thinking in negative contexts (i.e., congruence between the valence of the event and the outcome). In sum, Study 3 replicated early findings, such that cultural differences in positive thinking depended on positive/negative context, and it provided evidence for a psychological mechanism: Chinese (vs Euro-Canadian) people’s increased belief in the lay theory of change explained some of the cultural differences in positive thinking.

Figure 4

Belief in lay theory of change mediates the relationship between culture (Chinese vs Euro-Canadian) and proportion of congruent outcomes.

Note. Reported coefficients represent unstandardized effects. Indirect effect = −.04 [−.08, −.01]. Total effect (summing indirect and direct effects) = −.35 [−.39, −.30]. PROCESS version 3.3, model 4; 10,000 iterations.

General Discussion

Psychological research often documents benefits of positive thinking (; ), but relatively little work explores when and how cultural groups differ in optimism. The present research identifies a contextual moderator that shapes cross-cultural differences in positive thinking. Consistent with cultural differences in lay theories of change (; ), we found that relative to Euro-Canadians, Chinese thought more negatively in positive contexts and more positively in negative contexts. The findings were obtained through diverse approaches to evaluating positive thinking. Studies 1-2 concerned the likelihood of positive/negative outcomes following from specific hypothetical events occurring to the respondent him/herself, whereas Study 3 targeted “people” in general (e.g., the outcomes of “a person getting mugged,” emphasis added) rather than the respondents themselves. Similarly, Study 1 used rating scales of fixed outcomes, Study 2 used a forced-choice between fixed outcomes, and Study 3 used an open thought listing/rating task. The breadth of measurement types in our work provides confidence that the effect observed is not localized to one scale or stimulus set but is valid across paradigms (see ). This breadth matches our conceptualization of positive thinking, which is not specific to self-relevant thoughts or particular response formats.

Theoretical Implications

The present research has important implications for cultural psychology. First, it contributes to an understanding of cultural variation. Unlike some theories of culture that propose “main effect” differences between groups (e.g., individualism versus collectivism), the present research is congruent with a Culture × Context perspective. That is, instead of viewing cultural differences as fixed distinctions, the present work examines how culture and context interact using a flexible, cognitive approach (congruent with ; ; ; ). Differences in positive thinking are not absolute but rather are relative, driven by distinct thinking styles that people from each cultural sphere use to make future predictions based on present circumstances. To provide evidence of this underlying cognitive mechanism, we have shown that Chinese hold a stronger belief in change, conceptually replicating . This tendency to anticipate change partially accounts for less positive thinking in positive contexts and more positive thinking in negative contexts among Chinese than among Euro-Canadians. The lay theory of change only provides a partial account, as the direct effect of culture on positive thinking remains significant in the mediation model, suggesting that other factors are likely contributing to the effect (although measurement error in the mediator can also prevent mediation from being “complete”; ).

Second, these findings contribute to a growing understanding of how cultural differences can be situationally specific, an idea best captured by moderation effects in which cultural differences in emotion, cognition, and/or behaviour themselves differ depending on contextual factors in the environment (; ; ; ; ). In a very different context, for example, demonstrated how cultural and contextual factors may best be viewed as interactive. Rather than Southerners simply being “more violent” than Northerners in the U.S. (i.e., a fixed cultural difference), these researchers demonstrated that Southerners engaged in increased aggression only after an honor threat had occurred (i.e., culture depending on context). Adopting a Culture × Context perspective also avoids simplifying cultural groups into fixed stereotypes () because this perspective demonstrates how cultural differences shift from situation to situation. Although Culture × Context perspectives have been explored for aggression and emotion regulation, a similar perspective concerning positive thinking has yet to be taken, and our research provides this.

The present findings join some prior work that highlights how positive thinking as captured by optimism specifically can be contextually sensitive. For instance, people think positively about their test results long before receiving them, but this tendency fades as the actual return of test results draws nearer (). suggest that people have less positive thoughts about the future when they are forced to confront the possibility of a bad outcome. We agree that positive thinking can be driven by situational factors, and our findings suggest that culture moderates such situational effects.

Engaging in more or less positive thinking in different contexts may have practical implications, for example, for planning and behavioral responses during public health emergencies. Before the COVID-19 outbreak when things were going well, positive thinking could entail poor planning or prevention preparedness, whereas negative thinking could prompt vigilance. During the pandemic when things are developing in a negative direction, positive thinking may be associated with taking the necessary measures and staying hopeful, whereas negative thinking may be associated with anxiety, despair, and even giving up on protective behaviors. Understanding culturally-distinct patterns of response to the vicissitudes of events is important especially when events have national or even global effects.

Limitations and Future Directions

One limitation of the present research is that it is based only on university students, and only two cultures. Future research should expand the samples to non-university samples and to include other cultural groups, which would allow us to examine if the phenomenon goes beyond the cultures we studied. For example, Russians (versus Americans) are sometimes characterized as inclined towards negative thinking (), but some research indicates that Russians (compared to Americans) engage in more negative or more positive thinking only depending on the topic (; ). Cross-topic variance speaks against “main effect” accounts in which Russians or Americans engage in invariantly more positive or negative thinking, and it may instead suggest that a different thinking style produces more or less positivity among Russians (compared to Americans) according to context. For example, demonstrated that Russians (vs Americans) display more field dependence, and field dependence is closely associated with holistic, dialectical thinking styles (). Thus, Russian tendencies towards positive or negative thinking may vary across topic because they are dependent on context (e.g., whether the topic is perceived as currently positive or negative). Future research could, therefore, explore if our theoretical position helps to account for other cultural differences as discussed above.

Another limitation is that we used only hypothetical scenarios in the present studies. Future work should examine cultural differences in people’s responses to real life positive and negative events. Indeed, we think that positive thinking has a clear relevance to real-world events such as people’s likely saving behaviors given rising and falling stock markets (e.g., ), people’s construal of pandemics (; ), actions taken during natural disasters and pandemics (e.g., ), and many other global issues. At the time of this writing, our results have relevance to the likely expectations and reactions that people from different cultural backgrounds may have to the COVID-19 pandemic. As a key topic during the pandemic (), the mental health of health care workers, who must cope with the negative circumstances of being undersupplied and/or overloaded with patients, may be enhanced through positive thinking. Training people to think about positive outcomes of a negative event (e.g., pandemics can serve as a “wake-up call” for governments to develop clear public safety protocols for global emergencies) may help them to better cope with the pandemic situation. Indeed, positive thinking has been linked with numerous benefits for health-care workers, including better coping strategies and more seeking of social support when needed (). Understanding when cultures will engage in positive thinking based on different contexts can therefore be of assistance in theoretical and applied contexts alike.

In addition, it is helpful to have a scale to measure lay theories of change, although the scale we have developed requires further testing and improvement, especially in the cross-cultural context, to improve its measurement invariance across groups. It is important to note, however, that our results remained consistent whether we used all of items on the lay theory of change scale or used only the subset of items that were measurement-invariant across cultures. This indicates a robustness to our effects, and further suggests that measurement non-invariance does not account for our findings.

Conclusion

The present work re-examines positive thinking through a Culture × Context interactive lens. We have shown more positive thinking among Chinese than among Euro-Canadians in response to negative events, but less positive thinking among Chinese than among Euro-Canadians in response to positive events. The present research highlights how culture and situation can work together to influence people’s psychological responses.

Appendix Lay Theory of Change Scale

1 = strongly disagree

2 = moderately disagree

3 = slightly disagree

4 = neutral

5 = slightly agree

6 = moderately agree

7 = strongly agree

Two people who were once strangers are likely to become good friends to each other; similarly, two people who were once friends are likely to become strangers to each other.

A competent person always performs well; as well an incompetent person always performs poorly. (R)

Two people who once hated each other are likely to become lovers; similarly, two people who once loved each other are likely to become enemies. **

Useful things are always useful, and useless things are always useless. (R)

A competent person in one situation is likely to be incompetent in another situation, and an incompetent person in one situation is likely to be competent in another situation.

True friends always will be friends, and true strangers always will be strangers. (R)

Something good in one situation is likely to become bad in another situation; as well, something bad in one situation is likely to become good in another situation.

A rich person is likely to become poor, and a poor person is likely to become rich. **

Simple issues are always simple, and complicated issues are always complicated. (R)

Something good is likely to lead to something bad, and something bad is likely to lead to something good. **

Something useful in one situation becomes useless in another situation; similarly, something useless in one situation becomes useful in another situation.

Note. Items marked ** were found to be measurement invariant (see Supplementary-2). Items marked (R) are reverse-coded.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) Grants to Ji (410-2003-1043; 435-2018-0061), and a SSHRC award to Vaughan-Johnston (#767-2018-1484).

Supplemental Material Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Li-Jun Ji

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6319-0580

Thomas I. Vaughan-Johnston

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4682-481X

1. Rather than focusing on the relative frequency of positive and negative self-relevant thoughts and emotions, these papers investigated the copresence of positive and negative thoughts/emotions (i.e., ambivalence). Nonetheless, they demonstrate that lay theories about dialecticism can underlie East-West cultural differences about positive and negative emotions/thoughts.

2. Due to a clerical error, age was not collected in this study.

3. A pretest confirmed that both Chinese and Euro-Canadians agreed that these responses were positive and negative respectively (according to one-sample t-tests for each stimulus compared against 0, calculated separately for Chinese and Euro-Canadians; ts > |7.39|, ps < 0.031, ds > |0.27|).

4. We also measured trait optimism with LOT-R () and found a significant cultural difference: F(1, 241) = 20.83, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.080. Surprisingly, Chinese had higher optimism scores (M = 3.80, SD = 0.62) than did Euro-Canadians (M = 3.41, SD = 0.69). The LOT-R was uncorrelated with the binary outcome expectancy choice, r(243) = 0.10, p = .130.

5. We ran two follow-up analyses; in both cases, in these logistic regression, each covariate was entered as an interaction covariate () with all lower-order effects. The first analysis used gender as a covariate because gender was unbalanced across the cultures; the culture X condition interaction remained significant. The second analysis entered positive mood and negative mood as separate interactive covariates; the culture X condition interaction remained significant.

6. See the full scale in appendix. Normally researchers avoid double-barreled questions. But in this special case when we want to measure people’s belief in cyclical change—events can change from one extreme to another, and vice versa—these double-barreled questions are necessary to capture the belief we intended to measure. For example, one has to believe in both “a rich person is likely to become poor” and “a poor person is likely to become rich” in order to score high on the belief in cyclical change.

7. We established partial measurement invariance (configural, metric, and scalar) with a subset of three LTC items (see appendix). Group differences were consistent when we evaluated only these items, and thus cultural differences are not driven by measurement non-invariance. The main study results are presented with the full 11-item LTC scale because, predictably, reliability dropped for the three-item scales (α = 0.51 and 0.48 for Chinese and Canadians, respectively).

References

- Abramson L. Y., Seligman M. E., Teasdale J. D. (1978). Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 87(1), 49–74.

- Bandura A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

- Baron R. M., Kenny D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

- Boldor N., Bar-Dayan Y., Rosenbloom T., Shemer J., Bar-Dayan Y. (2012). Optimism of health care workers during a disaster: A review of the literature. Emerging Health Threats Journal, 5(1), 7270.

- Carver C. S., Scheier M. F. (2009). Optimism. In Leary M. R., Hoyle R. H. (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 330–342). The Guilford Press.

- Carver C. S., Scheier M. F. (2014). Dispositional optimism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(6), 293–299.

- Chang E. C. (1996). Cultural differences in optimism, pessimism, and coping: Predictors of subsequent adjustment in Asian American and Caucasian American college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 43, 112–123.

- Chang E. C., Asakawa K. (2003). Cultural variations on optimistic and pessimistic bias for self versus a sibling: Is there evidence for self-enhancement in the West and for self-criticism in the East when the referent group is specified? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), 569–581.

- Chang E. C., Maydeu-Olivares A., D’Zurilla T. J. (1997). Optimism and pessimism as partially independent constructs: Relationship to positive and negative affectivity and psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 23(3), 433–440.

- Chen C., Lee S. Y., Stevenson H. W. (1995). Response style and cross-cultural comparisons of rating scales among East Asian and North American students. Psychological Science, 6(3), 170–175.

- Chen Q., Liang M., Li Y., Guo J., Fei D., Wang L., He L., Sheng C., Cai Y., Li X., Zhang Z., Wang J. (2020). Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(4), e15–e16.

- Choi I., Koo M., Choi J. A. (2007). Individual differences in analytic versus holistic thinking. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(5), 691–705.

- Ciccone S. (2003). Does analyst optimism about future earnings distort stock prices? The Journal of Behavioral Finance, 4(2), 59–64.

- Cohen P., Cohen J., Aiken L. S., West S. G. (1999). The problems of units and the circumstance for POMP. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 34, 315–346.

- Davidov E., Dülmer H., Schlüter E., Schmidt P., Meuleman B. (2012). Using a multilevel structural equation modeling approach to explain cross-cultural measurement noninvariance. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 43(4), 558–575.

- Dember W. N., Martin S. H., Hummer M. K., Howe S. R., et al. (1989). The measurement of optimism and pessimism. Current Psychology: Research Reviews, 8, 102–119.

- Doctor R. M., Goldenring J. M., Chivian E., Mack J. E., Waletzky J. P., Lazaroff C., Gross T. (1988). Self-reports of Soviet and American children on worry about the threat of nuclear war. Political Psychology, 9(1) 13–23.

- Falk C. F., Dunn E. W., Norenzayan A. (2010). Cultural variation in the importance of expected enjoyment for decision making. Social Cognition, 28(5), 609–629.

- Fischer R., Chalmers A. (2008). Is optimism universal? A meta-analytical investigation of optimism levels across 22 nations. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(5), 378–382.

- Fontenelle G. A., Phillips A. P., Lane D. M. (1985). Generalizing across stimuli as well as subjects: A neglected aspect of external validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 70(1), 101–107.

- Fritz M. S., MacKinnon D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18(3), 233–239.

- Gallagher M. W., Lopez S. J., Pressman S. D. (2013). Optimism is universal: Exploring the presence and benefits of optimism in a representative sample of the world. Journal of Personality, 81(5), 429–440.

- Gierlach E., Belsher B. E., Beutler L. E. (2010). Cross-cultural differences in risk perceptions of disasters. Risk Analysis: An International Journal, 30(10), 1539–1549.

- Giltay E. J., Geleijnse J. M., Zitman F. G., Hoekstra T., Schouten E. G. (2004). Dispositional optimism and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in a prospective cohort of elderly Dutch men and women. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61(11), 1126–1135.

- Hardin E. E., Leong F. T. (2005). Optimism and pessimism as mediators of the relations between self-discrepancies and distress among Asian and European Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(1), 25–35.

- Hayes A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications.

- Heine S. J., Kitayama S., Lehman D. R., Takata T., Ide E., Leung C., Matsumoto H. (2001). Divergent consequences of success and failure in Japan and North America: An investigation of self-improving motivations and malleable selves. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(4), 599–615.

- Heine S. J., Lehman D. R. (1995). Cultural variations in unrealistic optimism: Does the west feel more invulnerable than the east? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 595–607.

- Hofstede G. (1980). Culture’s consequences. Sage Publications.

- Hong Y. Y., Morris M. W., Chiu C. Y., Benet-Martinez V. (2000). Multicultural minds: A dynamic constructivist approach to culture and cognition. American Psychologist, 55(7), 709–720.

- Jacobson J. A., Ji L. J., Ditto P. H., Zhang Z., Sorkin D. H., Warren S. K., Legnini V., Ebel-Lam A., Roper-Coleman S. (2012). The effects of culture and self-construal on responses to threatening health information. Psychology & Health, 27(10), 1194–1210.

- Ji L. J. (2005). Culture and lay theories of change. In Sorrentino R. M., Cohen D., Olson J., Zanna M. (Eds.), Culture and Social Behavior: The Tenth Ontario Symposium (pp. 117–135). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Ji L. J. (2008). The leopard cannot change his spots, or can he? Culture and the development of lay theories of change. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(5), 613–622.

- Ji L. J., Guo T., Zhang Z., Messervey D. (2009). Looking into the past: cultural differences in perception and representation of past information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(4), 761–769.

- Ji L. J., Nisbett R. E., Su Y. (2001). Culture, change, and prediction. Psychological Science. 12, 450–456.

- Ji L. J., Schwarz N., Nisbett R. E. (2000). Culture, autobiographical memory, and behavioral frequency reports: Measurement issues in cross-cultural studies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(5), 585–593.

- Ji L. J., Zhang Z., Guo T. (2008). To buy or to sell: Cultural differences in stock market decisions based on stock price trends. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 21(4), 399–413.

- Ji L. J., Zhang Z., Usborne E., Guan Y. (2004). Optimism across cultures: In response to the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 7(1), 25–34.

- Judd C. M., Westfall J., Kenny D. A. (2012). Treating stimuli as a random factor in social psychology: A new and comprehensive solution to a pervasive but largely ignored problem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(1), 54–69.

- Kassinove H., Sukhodolsky D. G. (1995). Optimism, pessimism and worry in Russian and American children and adolescents. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 10(1), 157–168.

- Kohut M. L., Cooper M. M., Nickolaus M. S., Russell D. R., Cunnick J. E. (2002). Exercise and psychosocial factors modulate immunity to influenza vaccine in elderly individuals. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 57(9), M557–M562.

- Koo M., Oishi S. (2009). False memory and the associative network of happiness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(2), 212–220.

- Kühnen U., Hannover B., Roeder U., Shah A. A., Schubert B., Upmeyer A., Zakaria S. (2001). Cross-cultural variations in identifying embedded figures: Comparisons from the United States, Germany, Russia, and Malaysia. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(3), 366–372.

- Lee Y. T., Seligman M. E. P. (1997). Are Americans more optimistic than the Chinese? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 32–40.

- Leung A. K. Y., Cohen D. (2011). Within-and between-culture variation: Individual differences and the cultural logics of honor, face, and dignity cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(3), 507–526.

- Lockwood P., Marshall T. C., Sadler P. (2005). Promoting success or preventing failure: Cultural differences in motivation by positive and negative role models. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(3), 379–392.

- MacKinnon D. P., Krull J. L., Lockwood C. M. (2000). Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science, 1(4), 173–181.

- Malouff J. M., Schutte N. S. (2017). Can psychological interventions increase optimism? A meta-analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(6), 594–604.

- Matsumoto D. (2007). Culture, context, and behavior. Journal of Personality, 75(6), 1285–1320.

- Matsumoto D., Grissom R. J., Dinnel D. L. (2001). Do between-culture differences really mean that people are different? A look at some measures of cultural effect size. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(4), 478–490.

- Nisbett R. E. (2003). The Geography of Thought: How Asians and Westerners think differently ... and why. The Free Press.

- Nisbett R. E., Cohen D. (1996). Culture of honor: The psychology of violence in the south. Westview Press.

- Nisbett R. E., Peng K., Choi I., Norenzayan A. (2001). Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychological Review, 108, 291–310.

- Oishi S., Diener E. (2003). Culture and well-being: The cycle of action, evaluation, and decision. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(8), 939–949.

- Peale N. V. (1952). The power of positive thinking. Prentice Hall.

- Peng K., Nisbett R. E. (1999). Culture, dialectics, and reasoning about contradiction. American Psychologist, 54(9), 741–754.

- Peterson C., Seligman M. E. (1984). Causal explanations as a risk factor for depression: Theory and evidence. Psychological Review, 91(3), 347–374.

- Scheier M. F., Carver C. S. (1985). Optimism, coping and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology, 4, 219–247.

- Scheier M. F., Carver C. S., Bridges M. W. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1063.

- Scheier M. F., Carver C. S., Bridges M. W. (2001). Optimism, pessimism, and psychological well-being. In Chang E. C. (Ed.), Optimism and pessimism: Implications for theory, research, and practice (pp. 189–216). American Psychological Association.

- Scheier M. F., Matthews K. A., Owens J. F., Magovern G. J., Lefebvre R. C., Abbott R. A., Carver C. S. (1989). Dispositional optimism and recovery from coronary artery bypass surgery: The beneficial effects on physical and psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1024–1040.

- Segerstrom S. C. (2005). Optimism and immunity: Do positive thoughts always lead to positive effects? Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 19(3), 195–200.

- Shepperd J. A., Ouellette J. A., Fernandez J. K. (1996). Abandoning unrealistic optimism: Performance estimates and the temporal proximity of self-relevant feedback. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(4), 844–855.

- Shifren K., Hooker K. (1995). Stability and change in optimism: A study among spouse caregivers. Experimental Aging Research, 21(1), 59–76.

- Spencer-Rodgers J., Boucher H. C., Mori S. C., Wang L., Peng K. (2009). The dialectical self-concept: Contradiction, change, and holism in East Asian cultures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(1), 29–44.

- Spencer-Rodgers J., Peng K., Wang L. (2010). Dialecticism and the co-occurrence of positive and negative emotions across cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 41(1), 109–115.

- Spencer-Rodgers J., Peng K., Wang L., Hou Y. (2004). Dialectical self-esteem and East–West differences in psychological well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(11), 1416–1432.

- Stephan W. G., Ageyev V., Stephan C. W., Abalakina M., Stefanenko T., Coates-Shrider L. (1993). Measuring stereotypes: A comparison of methods using Russian and American samples. Social Psychology Quarterly, 56(1), 54–64.

- Sweeny K., Carroll P. J., Shepperd J. A. (2006). Is optimism always best? Future outlooks and preparedness. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(6), 302–306.

- Szondy M. (2004). Optimism and immune functions. Mental higienees Pszichoszomatika, 5, 301–320.

- Taylor S. E., Brown J. D. (1988). Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 103(2), 193–210.

- Taylor S. E., Brown J. D. (1994). Positive illusions and well-being revisited: Separating fact from fiction. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 21–27.

- Tsai W., Lau A. S. (2013). Cultural differences in emotion regulation during self-reflection on negative personal experiences. Cognition & Emotion, 27(3), 416–429.

- Västfjäll D., Peters E., Slovic P. (2013). Affect, risk perception and future optimism after the tsunami disaster. In The feeling of risk (pp. 137–150). Routledge.

- You J., Fung H. H., Isaacowitz D. M. (2009). Age differences in dispositional optimism: A cross-cultural study. European Journal of Ageing, 6(4), 247–252.

- Yzerbyt V. Y., Muller D., Judd C. M. (2004). Adjusting researchers’ approach to adjustment: On the use of covariates when testing interactions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40(3), 424–431.