Attachment classification distribution is largely considered to be consistent across populations, with normative patterns indicating an approximate 60% secure and 40% insecure distribution (). Some deviation to this has been observed among samples of at-risk children, including those of mothers suffering from depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (), maltreated children (), those of low socioeconomic status (), and those removed from families and placed into care (). While mediating factors may provide insight into such deviations in classification distribution among high-risk samples, research has also questioned whether this distribution is found among non-Westernized cultures and the universal applicability of the tools used to assess it ().

Culture as an influencing factor on attachment formation has garnered much interest since began developing the Strange Situation Procedure (SSP), widely considered to be the gold standard in attachment assessment among infants and young children. Informed by her observation of separation and reunion incidents between Ugandan infants and their mothers during the 1950s, Ainsworth established a tripartite classification system of attachment (), categorizing infant–mother attachment as either avoidant (A), secure (B), or resistant/ambivalent (C) [with Main & Solomon later adding a fourth classification—disorganized (D) in ]. Later, sought to apply the SSP to samples of American mother–infant dyads with similar distributions being observed. These findings paved the way for further testing of the SSP by other researchers sampling across a variety of populations, including parent–infant dyads from Japan (), Puerto Rico (), South Africa (), and Czechoslovakia (), ultimately lending support to the notion of a universal attachment distribution across cultures.

Researchers have increasingly considered the role cultural norms and values play in influencing caregiving practice and questioned the validity of current measures to assess attachment within non-Western contexts (e.g., ). In their review of the contextual and universal dimensions of attachment across cultures, observed that the majority of cross-cultural attachment research has at its foundation a fundamentally Western theoretical basis and methodology elicited to observe behavior (an etic perspective), which subconsciously disregards the value of behaviors specific to cultures to gather insight (an emic perspective). noted the paucity in research investigating cross-cultural factors that may produce variation in attachment distribution, which may partially account for a lack of culturally specific tools to approach cross-cultural attachment from an emic perspective. This research gap has consequently contributed to theories of attachment and measurement tools developed in the West being tested for their cross-cultural validity, leading to a questioning of the plausibility of applying tools based on typically Western values and principles to predominantly collectivist populations (). Such measures may lack sensitivity to identify culturally specific environmental and socioemotional factors that contribute to the development of attachment within other cultures and potentially lead to incorrect assumptions about attachment classifications between Western and non-Western populations (). It is therefore critical to understand potential mediating factors that give rise to divergent attachment distributions when using non-Western samples within the current body of literature, which may provide the foundation for the development of culturally specific attachment measures.

Measuring Attachment Classification Across Cultures

While it is established that much cross-cultural attachment research is approached from an etic perspective, the SSP continues to be lauded as a culturally valid attachment measure yielding a generally consistent classification distribution across populations. It is considered capable of providing enough sensitivity to allow for the identification of potential cross-cultural differences (e.g., ). demonstrated an emergence of attachment clusters particular to certain populations as part of their meta-analysis of 1,900 attachment classifications across eight different countries (Germany; Japan; America; Israel; the Netherlands; Great Britain; Sweden; and China). It was identified that although secure classifications were most prevalent across all populations (congruent with typical SSP observations), avoidant classifications were more evident among Western European countries and resistant/ambivalent classifications more characteristic in Israel and Japan. Explanations for such variations were limited to possible disparity in socioeconomic status of participants between studies and propagation of standard parenting concepts originating from the West, with little exploration of potential culturally specific moderating factors.

The SSP has also proved able to identify unexpected attachment classifications across cultures where mother–infant behaviors are not dissimilar to the typically Western parenting styles from which the SSP was modeled. In studying attachment behaviors of the Dogon ethnic group of West Africa, identified a 67% secure/0% avoidant/8% resistant and 25% disorganized distribution among mothers and their infants. As with Van Ijzendoorn and Kroonenberg’s sample, secure attachment was observed to be the dominant classification; however, a high percentage of disorganized attachment was also observed among this group. Such classifications within a population whose parenting style was characterized by prolonged periods of immediate proximity and responsiveness appears incongruent with a key component of attachment theory relating to sensitivity and development of secure attachment (). , however, suggested that these disorganized classifications were likely due to the level of stress placed upon infants by the unfamiliar and inconsistent separation and reunion protocols of the SSP, which were not typically experienced by infant–mother dyads in the Dogon ethnic group.

As well as inter-cultural deviations from expected distributions, the SSP has produced intracultural variations in attachment behavior within populations of the same religious and collectivist backgrounds. , in their application of the SSP with two groups of Jewish infants residing within various Israeli kibbutz, identified higher instances of insecure type classifications (52%) among infants residing in communal sleeping arrangements with multiple non-parental caregivers than those being cared for within their homes by primary caregivers (35% insecure). Such classifications may be expected given the benefit to be gained through increased proximity of an infant to their primary caregiver, and too demonstrated, as part of her Ugandan observations, that the presence of multiple caregivers alone was not a predictor of attachment security, but rather the presence of a mother–infant bond. Interestingly, Sagi et al. did not identify any significant differences in daytime interaction between both groups of infants and their mothers, perhaps indicating that insecure attachment classifications observed in one point of time may not entirely reflect a general or accurate level of attachment security. Such findings reinforce the importance of emic-informed measures to account for those differences and provide a clearer explanation to avoid incorrect assumptions being made about the attachment relationship between a child and their caregiver.

Attachment in Indigenous Cultures

Attachment research within Indigenous cultures has received less focus than other collectivist and Western cultures, resulting in a chasm in knowledge as to the fidelity of current measurement tools utilized within Indigenous cultures. To inform culturally valid measurement tools, it is crucial to consider whether classic attachment concepts are observed within and can be applied to Indigenous cultures. For example, the sensitivity hypothesis surmises that secure attachment is the result of sensitive caregiving (, ), in which infants with caregivers responsive to their needs are hypothesized to be more securely attached as their needs are adequately and appropriately met. What denotes responsive parenting, however, is shown to vary interculturally. New Zealand Māori mothers strongly connected to traditional Maoridom culture, for instance, typically co-sleep with infants to alleviate their distress upon separation, thus subsequently responding to their need for comfort during sleeping periods (). Such parenting practice can be seen as congruent with Ainsworth’s sensitivity hypothesis; however, some unresponsive Western practices, such as allowing crying infants to self-soothe through separation during sleep (), challenge this hypothesis. The rationale behind such practice allows for the development of self-regulation skills () and future independence, hallmarks of individualistic culture characteristic of countries including contemporary New Zealand, in contrast to interdependence favored in more collectivist populations. However, how such practice among Māori mothers translates into infant attachment classification remains unknown, owing to the dearth in such research. The sensitivity hypothesis may also not fully account for the presence of multiple attachment systems in some Indigenous cultures, particularly where primary caregiving is shared among several figures (). observed that infants among the Indigenous Aka foragers received responsive caregiving, including breastfeeding, from multiple group members while maintaining a stable bond with their birth-mother. While a Western model of caregiving may not typically favor responsiveness from multiple caregivers, found that exposure to multiple attachment systems provides children with greater social, emotional, and physical attention, and stimulation compared to those with a single attachment relationship. Furthermore, the sensitivity hypothesis may overlook that, in some Indigenous cultures, the concept of attachment itself may extend beyond the immediate family to include ancestors, land, and water elements essential to Indigenous identity and wellbeing (). Although this may be perceived as an abstract form of responsive parenting when viewed through a Western lens, it represents a critical developmental foundation within Indigenous cultures.

Another fundamental principle within attachment theory, the secure-base hypothesis (), suggests that infants and children who are securely attached display a greater readiness to venture away from their caregivers to explore and engage in play. This stands in contrast to those who exhibit insecure attachment patterns (). Bowlby believed that this inclination results from the formation of an internal working model (IWM) of attachment, allowing infants and children to maintain an internal representation of their caregiver even when physically distant. This internal model accordingly provides reassurance that their caregiver will be accessible upon their return.

The interpretation of the secure-base hypothesis in collectivist cultures, like that of the Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, presents a unique challenge. In some Indigenous communities, there is an observed tendency to discourage infants from exploring away from their caregiver(s) until they reach 2 years of age (). This raises questions about how the secure-base hypothesis applies in such contexts. From a Western viewpoint, an infant’s hesitance to stray away from their caregiver might be interpreted as a sign of insecure attachment. However, research, informed through discussion with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community members, indicates that such parenting practice can be implemented as a means to strengthen community connection, thereby fostering a positive Aboriginal identity and sense of security. This may be considered a more valuable component of attachment formation, serving to support the survival and continuity of Australian Indigenous culture. In contrast, Canadian Inuit infants and small children are afforded greater freedom to explore and engage in a diverse range of activities away from their caregivers, with their autonomy encouraged based on their individual capabilities (). While within a Canadian Inuit community this is regarded as vital for progression through developmental stages, a Western perspective might perceive such freedom as indicative of a more permissive parenting style with less control, potentially raising concerns about a child’s safety.

Attachment security is widely believed to have a lasting impact on an infant’s social competence throughout their life, as suggested by the competency hypothesis (). However, it is important to note that the concept of social competence is culturally relative and may depend on the extent to which a culture values independence versus interdependence. Many Indigenous cultures, for instance, prioritize values such as early self-reliance, fostering interdependence, displaying restraint of negative emotions (especially toward Elders), and emphasizing loyalty to community and spiritual connectedness. These values differ from the Western approach, which encourages self-exploratory behavior, self-expression, emotional regulation, and resilience in children (). In the case of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, these culturally rooted behaviors may be mistakenly assessed as signs of insecure attachment, stemming from parenting practices viewed negatively in Western countries (). Such limitations recognized within attachment theory therefore call for a cautious approach when considering the use of standardized attachment tools in Indigenous communities (e.g., ) or indeed any other non-Western culture.

Ramifications of Incompatible Attachment Measures in Indigenous Cultures

Conducting attachment assessments that fail to align with cultural norms, or do not consider diverse caregiving systems, can have profound consequences on the lives of children from culturally diverse backgrounds, particularly if they reflect inaccurate classifications. Attachment assessments are increasingly utilized in family court proceedings to guide decisions related to the removal of a child from families due to welfare issues (), the assessment of risk posed by caregivers (), and decisions relating to custody ().

In Australia, child protection systems consider professional judgment to assess a child’s vulnerability to harm () and a caregiver’s ability and willingness to protect their child (). These judgments include assessing risk, often based on observations of family functioning, and an assessment of attachment between a child and their caregiver (). Attachment assessments, therefore, play a pivotal role in Australian court proceedings, influencing child removal from, and reunification with, family ().

Similar attachment measures, rooted in attachment theory, have been used to inform risk assessments affecting the permanent placement of children in Canadian court proceedings, including post-removal from families of origin (). expressed concern about the preference of Canadian family courts to utilize a predominantly Western approach to the child-welfare system fundamentally incongruent with traditional Aboriginal family systems, with adding that the practice of applying culturally uninformed assessments to Indigenous families carries a risk in failing to identify appropriate and safe parenting within the context of traditional Aboriginal parenting.

Globally, Indigenous children are disproportionately represented in child protection systems compared to their non-Indigenous peers (; ) and face a higher likelihood of being placed in out-of-home care (). In Australia, despite constituting only 6% of the total population, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children (aged 0–17 years) account for a significant 43.7% of the out-of-home care population (). Similarly, in New Zealand, Māori and Pacific Islander children account for 64% of those placed in out-of-home care, a stark over-representation compared to the predominantly Pākehā (NZ European) population (). In North America, Native American children, constituting only 1% of the overall child population, represent 2% of those in foster care (), while in Canada, despite comprising just 7.7% of all children under 15 years, Indigenous children make up 53.8% of those in foster care placements ().

While it is not implied that the removal of a child from their family solely occurs because of culturally incongruent attachment measures, there are evident limitations in applying attachment theory to Indigenous cultures, which casts doubt about the reliance on Western-developed attachment measures to inform critical decisions concerning Indigenous children. Consideration and knowledge of attachment concepts in Indigenous cultures are therefore critical to comprehend family structures and correctly interpret the attachment process relating to those communities ().

This systematic review aimed to provide a comprehensive and unbiased examination of relevant studies to answer the following questions:

Is there a reported difference in attachment distribution between Indigenous and non-Indigenous children?

What attachment measures are used with Indigenous samples?

Are attachment measures modified to consider specific cultural factors?

It was anticipated that findings could draw further attention to the problematic use of standardized assessments of attachment cross-culturally, which may disadvantage Indigenous populations, particularly children, and contribute to the growing body of evidence advocating for alternative means of assessing attachment in Indigenous populations.

Method

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRIMSA; ) was used to guide this systematic review to identify relevant English language, peer-reviewed, research articles that used attachment measures as per the inclusion criteria outlined below. Qualitative and quantitative research articles, of any year, were included.

Inclusion Criteria

Indigenous children and young people (aged up to, and including, 18 years) from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and America were selected as the target population for this systematic review. Viewed as predominantly individualistic in culture (), these countries are inhabited by Indigenous populations (i.e., Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, New Zealand Māori, Canadian First Nation, Métis, and Inuit, and Native American) that adopt predominantly collectivist cultures and may be viewed comparably in terms of Indigenous wellbeing (). Non-Indigenous children and young people of those same countries were selected as a comparison population.

Studies employing attachment assessment tools that categorized children into secure and non-secure classifications were selected for inclusion within this review. Due to the limited cross-cultural research on attachment, this review did not focus exclusively on studies that used the SSP and expanded its scope to include any measure that produced a categorical classification (e.g., Child Attachment Interview, ; Adult Attachment Interview [AAI], ). Categorical classifications were selected as the preferred measurement outcome to continuous classifications given their consistency and robustness ().

Search Strategy

To identify suitable studies, searches using PsychInfo, PsychArticles, Science Direct, and Embase were conducted between March 2022 and May 2022. Key search terms included target Indigenous populations and were broadened to capture a wide array of attachment-related studies. For each database, variants of the following search term were entered: “indigenous populations/OR exp alaska natives/OR exp american Indians/OR exp inuit/OR exp pacific islanders/OR torres strait islander.mp. OR maori.mp. OR australian aboriginal.mp. OR inuit/OR metis.mp. OR demographic characteristics/OR population/AND children.mp. OR non-indigenous populations.mp. AND attachment behavior/OR exp behavior/OR exp object relations/OR exp separation reactions/OR exp attachment disorders/OR exp attachment theory/OR exp parent child relations/OR exp separation anxiety/OR exp separation anxiety disorder/OR attachment disorders/OR attachment theory/OR exp Attachment Disorders/OR attachment.mp. OR exp Attachment Behavior/OR exp Attachment Theory/.” Backward citation searching was completed using Web of Science, and additional eligible studies were included in the review.

Study Selection

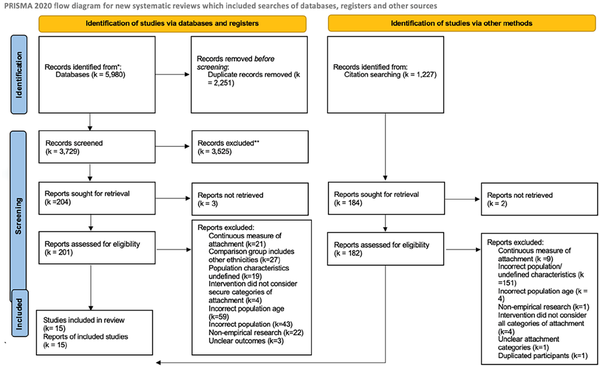

The initial search, conducted between March and May 2022, yielded 5,980 potentially suitable studies, from which 2,251 duplicates were removed using Endnote software. Title and abstract screening of the remaining 3,729 studies, and 1,227 records identified from the citation search, were conducted against the inclusion criteria by S.-L.B.T., from which 204 studies from the initial search and 184 studies from the citation search were subject to full-text screening by S.-L.B.T., and partial screening by PhD candidate A.L. S.-L.B.T. and A.L. conducted independent screening of the 204 initial studies (three of which could not be retrieved), and removed 198 studies assessed as ineligible (Figure 1 shows the study selection process). Next, S.-L.B.T. completed full text screening of the 184 citation studies (two of which could not be retrieved) and removed 171 records, resulting in a combined total of 14 eligible studies being included within the review. A re-run of the search completed in October 2023 resulted in one additional study, bringing the total number of eligible studies included in the review to 15.

Figure 1

PRISMA Diagram Showing Study Selection Process.

Data Extraction

Data extraction of the 15 studies was completed by S.-L.B.T. and S.M., using an Excel spreadsheet to record relevant data for each, including date and country in which the study took place, target population type (e.g., Australian Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander, NZ Māori, etc.) and size, comparator population type (e.g., Anglo-Australian, NZ European, etc.) and size, attachment intervention measure applied, distinct attachment classifications for target and comparison populations, and indication that cultural factors had been considered during study design (see Table 1). Given inconsistency across the studies in how attachment classifications were reported (i.e., some studies reported secure/insecure classifications only, whereas others reported secure/ambivalent/resistant insecure/disorganized attachment), insecure types were aggregated and classified as one category during data extraction. In addition, some studies included more than one measure of attachment over a defined timespan; however, this was often associated with participant attrition. As it was not possible to identify the cultural background of participants who left such studies, only the first-time attachment measure was reported on for this review. Furthermore, only those participants who had a recorded attachment score within the results section of each study were included within the recorded sample sizes. Any discrepancies were resolved between S.-L.B.T. and S.M. throughout the data extraction process.

Quality Assessment

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 18 () was selected to appraise the quality of included studies within this review. The MMAT offers the ability to critically appraise five categories of studies (including quantitative and qualitative studies) across an array of methodologies and has been designed specifically for systematic reviews. Consisting of two parts, the MMAT begins with two screening questions ensuring clear research questions are included within each study and that data collected suitably addresses those questions. Next, depending on the specific design of the study being appraised (e.g., qualitative, quantitative Randomized Controlled Trials [RCTs], Quantitative non-randomized, Quantitative descriptive or mixed methods), five further criteria relating to methodology quality were considered and recorded. Responses provided were given as a “yes” (sufficient information included), “no” (insufficient information), or “can’t tell” (unclear information within the study), with a comments section. S.-L.B.T. and S.M. completed quality assurance of all 15 studies and used a standard Excel spreadsheet to record responses and resolved any discrepancies as they occurred.

Results Synthesis

Narrative analysis was selected as an appropriate method to synthesize results, allowing for exploration of measures used to determine attachment classification, as well as procedural adjustments undertaken to account for cultural differences between target and comparison groups. Differences in attachment distribution between the groups were also to be described as part of this analysis.

Results

Study Characteristics

Of the 15 studies, 14 were completed in America and 1 in Canada. There were no eligible studies completed in either Australia or New Zealand. Studies were predominantly longitudinal (87%) and employed non-randomized control trial designs (k = 13), mixed methodological (k = 1), and randomized control trial (k = 1) designs. There was a total of 3,452 participants included across the studies, ranging in sample size from n = 33 to n = 1,044, and aged between 7 months and 15 years old (mean age = 32.6 months). More than half of the studies were completed when participants were aged 12 months. For this review, only those participants who received an attachment classification were included in the analysis. This meant that some sample sizes reported in this review were slightly lower than the original study sample size, where complete data collection did not occur. Several studies (k = 9) employed at-risk samples, such as infants of adolescent mothers, infants experiencing trauma and abuse, infants at risk of developmental disorders, and infants exposed to economic disadvantage, and poverty. Studies were conducted between the years 1980 and 2020.

Participants

Owing to the over-representation of American studies within the review, most participants were of American Caucasian and African American ethnicity (n = 3,333), and so the small number of Indigenous participants across the studies were of Native American background (n = 58). One American study () included n = 4 Native American, Eskimo (as referred to within the study) and Aleutian participants; however, no further composition breakdown of those participants was provided. Given the study was conducted in America, this review classified those participants as Native American. The same study also included an unspecified number of Pacific Islander participants; however, a failure to provide a specific sample size or the Pacific country of origin meant this number was unable to be counted as New Zealand Māori participants. Caucasian Canadian participants accounted for n = 61 of the aggregate sample, with no target Canadian First Nation, Métis, or Inuit population included as participants from the sole Canadian study (). Given no eligible Australian or New Zealand studies were identified for inclusion, there were no Aboriginal, Torres Straits Islander, or Māori participants. A small number of participants from other ethnic backgrounds were included where they formed part of a comparison population and where attachment classifications were indistinguishable. These included Hispanic, Asian, Middle Eastern, Caribbean, and biracial participants. Consensus was reached to include these studies, owing to the limited number of studies completed that included target Indigenous samples.

Attachment Classifications

All studies reported attachment distribution collectively for participant populations, without further classification reporting for Indigenous participants (or participants from other cultural backgrounds). Consequently, this review was unable to report on any differences in attachment distribution between Indigenous and non-Indigenous children.

Of the studies, six (k = 6) reported attachment classifications that fell within the scope of the typically reported 60% secure, 40% insecure distribution (, provided two separate samples with vastly different distributions), whereas seven studies (k = 7) reported higher incidents of insecure and lower secure attachment classifications. Two studies (k = 2) resulted in equal secure and insecure distributions. As expected, six of the studies (k = 6) that produced lower secure attachment scores were conducted on samples of at-risk children, including those of clinically depressed mothers (k = 1), exposed to various forms of trauma (k = 1), with adolescent mothers (k = 3), and those within impoverished families (k = 1).

Attachment Measures

SSP

Ainsworth’s SSP was the most utilized attachment measure, featuring in k = 12 studies, and was administered to infants and children between the ages of 12 and 25 months (mean age = 14.2 months). All SSP measures were undertaken under laboratory conditions; however, varying descriptions of the measure were provided across the studies. For example, k = 4 studies clearly reported usage of the original eight-episode method, inclusive of sequential separations and reunions (; ; ; ), whereas k = 7 studies provided limited or no information about how the SSP was employed in their studies, or whether any adjustments were made.

In study, the SSP was administered on two occasions; one when infants were 12 months old and another at 36 months, making adjustment to the second measure based on recommendation by . Adjustments in this second measure were limited in description to separation and reunion duration, in which the first period of separation occurred after 3 min for 3 min, followed by a 3-min reunion before a final 5-min separation. , however, failed to describe the initial SSP measure in the same level of detail, instead summarizing the procedure as two separation and reunion episodes, each with increasing levels of stress. No rationale was provided within the study for such adjustment between the ages or different approaches for the subsequent measure. Limited description of the conditions under which the infants were subject to increasingly stressful conditions was provided. , in their study, also failed to describe details of modifications made to their use of the SSP, which featured increasingly stressful situations and changes to social environments within each episode.

Evident across all studies which administered the SSP was a lack of adjustment made to account for the varying number of Indigenous participants, or consideration for how cultural confounds related to Indigenous status may have impacted attachment classification scores. study specifically sought a culturally diverse participant pool, while in their study utilized the highest number (n = 13) of Indigenous participants, yet neither study made any culturally relevant adjustment to the SSP measure to allow for attachment behaviors that may be specific to Indigenous populations. As classifications were not reported for Indigenous participants, it is not known whether the SSP measures used in these studies, or any of the studies, reflect the actual attachment classification that more accurately represents Indigenous culture.

AAI

The AAI () was administered to a group of older participants (age 15 years) in k = 1 study (). As with studies employing the SSP procedure, limited details were provided about the measure, including any adjustments made due to the presence of Indigenous participants within their sample. Similar to , also sought a culturally diverse participant pool (n = 200) for inclusion in their study yet did not make any culturally relevant adjustments to the AAI questioning or process to ensure its cultural relevance and validity.

Story Stem Task

A Story Stem Task measure, based on the method by and adapted by , was administered to participants, aged 10 to 12 years. This measure involved providing participants with a story stem containing an attachment theme to evoke an attachment behavior response. Participants were then asked to complete the story, using dolls, to depict what happened next. Originally designed for a pre- adolescent Israeli audience, Kerns et al. adapted the Story Stem Task for American participants, by using more relevant and relatable attachment themes. Whereas these measures appeared appropriate to suit the dominant American Caucasian sample selected for this study, there was no reporting on whether such scenarios were culturally relevant to Native American participants (n = 5) who also featured in the study.

Still Face Paradigm

The Still Face Paradigm, administered in k = 1 study () sought to evoke attachment behavior through three 2-min phases of engagement, still-face, and reunion between an adolescent mother and her infant at 7 months of age. Dyads were assigned to one of the two conditions—one in which close proximity was encouraged through regular wearing of a baby carrier and the second a non-carrying control group. The engagement phase of the measure involved mothers interacting with their infants for a 2-min period before pausing for 15 s and assuming a neutral facial expression (still face) while maintaining gaze with their infants. Mothers then resumed interaction (reunion) with their infants for a further 2 min, as observers recorded infant attachment responses. Despite the study recruiting participants from a variety of cultural backgrounds, in addition to one Native American dyad, no consideration was made toward potential cultural confounds which may have influenced attachment behaviors, particularly as they relate to baby-carrying behaviors and closeness which differ across cultures.

Across all studies reviewed, none made any measurement adjustment to account for the portion of Indigenous participants or the potentially relevant cultural practices that may have affected scoring through observable attachment behavior.

Methodological Considerations

Several studies adjusted their methodologies to include naturalistic observations of infant–mother dyads to measure non-attachment behaviors. For example, observed the interactive behavior between mothers and their infants at 6 months old, over two separate occasions in their home environments. Although attachment behavior in this study was measured using the SSP in a laboratory setting, home observations were used to determine the association of mother–infant interaction with attachment classification, which was found to be significantly associated. Such observations may prove useful in identifying cultural norms and behaviors that can provide crucial context around attachment classifications, although in the case of Bailey et al., such findings were either not identified or reported.

also included a home-based observation in their study to assess maternal stimulation of children’s cognitive development during a semi-structured play procedure, as part of a wide battery of measures. Attachment, however, was measured using the SSP under laboratory conditions. No culturally related behavior was identified or reported on during the study as a result of observations or testing.

As part of their study investigating the role of living arrangements and grandmother support in adolescent parenting and infant attachment security, conducted observations to assess Home Observation Measurement of the Environment (HOME) and Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale (NCATS) interactions. These measures assessed the quality of social, emotional, and cognitive experiences provided by a child’s home environment, and the quality of parent–child interaction, and provided researchers with an opportunity to examine the potential influence of cultural factors on HOME/NCATS scoring, including race. Findings indicated a significant relationship between race and HOME/NCATS scores, living arrangements, and grandmother support provided to adolescent mothers. However, no statistical test to determine the relationship between race and attachment security was incorporated into the methodological design, nor was there a clear description of the validation process for using these measures with Indigenous samples.

Cultural Considerations

A range of confounding factors and variables were identified in the 14 review studies. Factors included mother’s marital status; infant sex; child parity at birth; cognitive function; developmental factors; infant temperament, as well as various risk factors (early maltreatment, parental depression, and parental life stress). Race, or ethnicity, was controlled for or considered as a variable affecting measures in five studies which included participants from other cultural backgrounds, alongside Indigenous participants. These studies yielded mixed findings in that three studies found race not to influence attachment classification (; ; ) and two found that it did (; ). However, due to the lack of classification reporting for each cultural group, and no incorporated test for Indigenous status, findings could not be specifically attributed to Indigenous participants. The importance of including such tests is highlighted in study, whose findings indicated differences in living arrangements and levels of grandmother social support between White and non-White adolescent mothers, which included Native American participants. Non-White adolescent mothers were more likely to live alone with their infants yet receive greater levels of grandmother support compared to White adolescent mothers living alone. Furthermore, higher levels of infant attachment security were found to be associated with greater levels of grandmother support when adolescent mothers resided alone. However, findings unique to each participating cultural group were not provided, and despite disparities in findings across race, the study did not explore the potential causes of these differences, missing an opportunity to consider how social support can be influenced by cultures, particularly collectivist Indigenous cultures such as Native American.

Discussion

During the review period, literature on attachment classification in Indigenous populations was limited, particularly in studies focused on Australian, New Zealand, and Canadian Indigenous populations. While a small number of attachment-related studies included Native American participants, their representation was substantially smaller than participants from comparison demographics, and there were no Indigenous-specific classifications reported among the findings. Such underrepresentation is not surprising, given the estimate that 90% of sampling pools in psychological research consist of American and European participants (). The deficit in Indigenous representation across attachment-related research is problematic and exposes a significant research gap which hinders our understanding of the cross-cultural validity of attachment measures, and risks reinforcing an assumption that cultural contextual factors do not necessarily influence attachment behavior and classification. Such a notion may therefore be the result of low Indigenous participation and limited representation across attachment research, rather than empirical evidence.

Several issues may help to explain this deficit. For instance, although notably absent in attachment research, Indigenous populations and communities are over-researched across other fields, particularly health (). noted that Indigenous communities often question the value of research they participate in, which tends toward further exposure of Indigenous disadvantage and a failure to translate findings into beneficial and tangible outcomes. Such repetitious experiences can result in a hesitancy of Indigenous communities to participate in research, particularly if facilitated by institutions perceived to be incongruent with, or unwilling to incorporate, Indigenous values and context (). This may be further complicated by a distrust toward non-Indigenous researchers who may portray cultural inaccuracies or fail to distinguish intracultural nuances, researchers perceived to conduct poorly designed research, or those who fail to consult with Indigenous communities as part of their design process (), as was evident across the studies within this review. Some researchers may further fail to safeguard Indigenous Cultural Intellectual Property () or adhere to First Nations Principles of Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession (). Research led by and within Indigenous communities, with the active support of the community and involvement of Indigenous scholars, may go some distance in addressing this underrepresentation in research and additionally provide valuable insights into how findings can be meaningfully interpreted within these communities.

Another key issue affecting Indigenous recruitment into research may lie in the locations selected from which to conduct a study. The majority of studies included within this review were conducted in metropolitan areas, utilizing local participant samples that might not typically represent Indigenous communities. In Australia, as is often the case for other countries with Indigenous populations, a significant portion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities reside within regional or remote areas, with those in urban areas often being dispersed (). Sampling exclusively from Indigenous populations in metropolitan areas may therefore lead to findings that do not fully represent the attachment systems, family structures, or kinship networks prevalent in rural or remote Indigenous communities (). To address this issue, cross-cultural attachment research should incorporate regions with higher Indigenous populations, in addition to metropolitan areas, to ensure more accurate and inclusive representation.

Although this review expanded its scope to encompass various categorical-based attachment measures, 12 studies adopted the SSP in their methodologies. Six of these studies showed a normative 60% secure and 40% insecure distribution consistent with previous research using this measure, whereas the remaining six using the SSP observed lower rates of secure and higher rates of insecure attachments. While this variability cannot be attributed to the non-significant representation of Indigenous participants, it is important that assumptions are not made about the generalizability of such classifications to Indigenous populations or participants of other cultural backgrounds included within these studies without further investigation into the causes of such variance. This is also evident for other attachment measures used in the remaining studies (k = 3), such as the AAI, Story Stem Task, and Global Rating Scale, which too yielded diverse distribution results.

The review further highlighted a notable limitation in adjustments made to methodologies in consideration of cultural contextual factors, which may have contributed to variance in observed attachment distribution. Given the widely recognized impact of culture on behavior, its incorporation into research design is critical to avoid invalid behavioral observations and outcomes (). While none of the reviewed studies directly investigated the link between cultural factors and attachment, one study () made minor adjustment to a measure to ensure cultural relevance to American participants, and two others (; ) included naturalistic observations to examine behavior within the home environment. However, no adjustments were made to any study to ensure measures aligned to Indigenous contexts. The findings across these studies may therefore be attributable to methodologies that overlook key cultural concepts or a failure to adapt for participants from varying cultural backgrounds. Such gaps in attachment research design might be addressed by considering and incorporating Indigenous caregiving models, which offer valuable insights into attachment concepts that contribute to healthy Indigenous child development (). The Indigenous Connectedness Framework (), for example, highlights the importance of fostering connections between an infant and their environment through establishing relationships with family, community, intergenerational ties, spirituality, and land to support healthy development. Unlike classical attachment theories, this framework has at its core multiple attachments that contribute to an Indigenous concept of wellbeing.

Similarly, the Social and Emotional Wellbeing (SEWB) model (), used by Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, views kinship and intergenerational connections as an attachment network spanning generations. As in the studies reviewed, culturally informed models appear largely unacknowledged by cross-cultural attachment researchers, despite their potential to inform research methodologies and subsequent measures and broaden our understanding of attachment across diverse cultural contexts.

These observations reinforce the importance of developing foundational knowledge of attachment systems across diverse cultures, which could be achieved through naturalistic and observation-based methods (e.g., ). Dedicated Indigenous attachment research is essential not only to validate Indigenous attachment systems but also to move beyond assumptions of universality and improve inclusivity in research (). Emic-based methods may further support the creation of culturally valid tools by identifying and accounting for culturally specific caregiving practices. For example, findings suggest that infant attachment security may be influenced by grandmother support, which varies with living arrangement and by race. However, there is insufficient understanding of how race and cultural factors influence attachment security and the mechanisms through which this occurs. This gap leaves a lack of culturally grounded content on which to build relevant measures, which may prove beneficial in determining what insecure attachment looks like in other cultures and how to appropriately respond.

In addition, clear reporting of culturally specific attachment classifications was absent in this and all other studies. This reporting is essential for identifying culturally unique patterns of attachment formation and to provide future directions for Indigenous-specific attachment research.

Despite a paucity within attachment studies, research informed by emic perspectives has proven effective in generating culturally validated findings in various fields. For example, emic-based measures have broadened our understanding of children’s psychosocial development across cultures (), facilitated cross-cultural diagnosis and prognosis of mental illnesses (e.g., ), and expanded our knowledge of culturally specific responses to key life events such as grief (). Moreover, they have contributed to culturally relevant service provision, such as assessing and responding to domestic violence in diverse immigrant populations (). Emic-based approaches have also led to the development of measurement tools tailored to Indigenous populations across various research fields. These tools include assessments of health and wellbeing in Canadian Indigenous populations (), interventions to treat depression and anxiety in Native American youth (), self-report measures of identity and wellbeing in New Zealand Māori (e.g., ), and therapeutic outcomes for Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (e.g., ). The failure of attachment research to advance measurement tools to ensure their applicability to Indigenous populations perpetuates a limited understanding of cultural influences in attachment dynamics and classification. This issue is particularly problematic when attachment measures inform assessments to guide decisions affecting the wellbeing of Indigenous children and young people, such as in family court proceedings. These potentially inaccurate measures risk subjecting Indigenous people to unnecessary or unjust service responses, such as the removal and sustained separation of children from their families, based on incorrectly perceived instances of unsafe parenting (e.g., ). Among Indigenous populations, such practices may be perceived as a continuation of policies enforced during colonization. This risks retraumatizing families already affected by the forced removal of children during that period and potentially creating a new generation of “stolen children” (. The paucity of research from target countries, known to have an over-representation of Indigenous children and young people in child protection systems, highlights a concerning omission.

All reviewed studies sought to investigate the relationship between attachment classification and a particular phenomenon and accordingly drew conclusions about the effect of secure and insecure attachment types on that particular phenomenon. However, there were inconsistencies between the studies as to what, if any, confounding factors were present and how they were controlled. Key factors such as parental trauma history and presence of support systems, significant life events, relevant infant medical history, sibling ordering, family stress, and environmental factors or exposure to bullying were not routinely considered as part of the designs yet were relevant factors that had the capacity to influence a participant’s performance or behavior during testing. The disregard of culturally relevant compounding factors across the studies may be on account of the relatively high ratio of participants from comparison populations to those target populations. Resultingly, these studies present a narrowed perception of the influence attachment classification had on selected behaviors and overlooked the opportunity to investigate whether cultural factors may moderate those relationships.

Conclusion

This systematic review is the first to investigate variations in attachment distribution between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, identify measures employed to determine those classifications and assess adaptations made to methodologies that account for Indigenous-specific cultural factors. However, the distinct lack of specific research investigating attachment formation and classification in Indigenous populations was a significant issue that hampered the review’s objective to adequately answer its research questions. As a result, robust conclusions from the synthesized literature regarding the association of specific attachment classifications with Indigenous populations were unable to be drawn. A limited variety of attachment measures were employed, as well as a lack of adjustment to account for a small number of Indigenous participants, further compounded these objectives, providing little guidance as to how best to measure Indigenous attachment. This systematic review concludes by highlighting the ongoing need of targeted and culturally informed research to explore potential underlying differences related to caregiver practice, cultural context, or family structure within Indigenous populations to aid understanding of their relationship with attachment classification, which in turn may translate to significantly broad societal, political, and contextual implications, and benefits that ensure better outcomes.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

Sarah-Louise B. Tkaczyk

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8996-9894

References

- Ahmad A., Sundelin-Wahlsten V., Sofi M. A., Qahar J. A., von Knorring A. L. (2000). Reliability and validity of a child-specific cross-cultural instrument for assessing posttraumatic stress disorder. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 9(4), 285–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s007870070032

- Ainsworth M. D. S. (1967). Infancy in Uganda: Infant care and growth of love. John Hopkins Press.

- Ainsworth M. D. S., Blehar M. C., Waters E., Wall S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Ainsworth M. D. S., Blehar M. C., Waters E., Wall S. (2015). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Routledge.

- Ainsworth M. D. S., Wittig B. A. (1969). Attachment and exploratory behaviour of one-year olds in a strange situation. In Foss B. M. (Ed.), Determinants of infant behaviour (Vol. 4, pp. 113–136). Methuen.

- Arts Law Centre of Australia. (2024). Indigenous cultural and intellectual property (ICIP). Arts Law Centre of Australia. https://www.artslaw.com.au/information-sheet/indigenous-cultural-intellectual-property-icip-aitb/

- Atwool N. (2016). Journeys of exclusion: Unpacking the experience of adolescent care leavers in New Zealand. In Mendes P., Snow P. (Eds.), Young people transitioning from out of home care: International research, policy and practice (pp. 309–328). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2021). Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples/estimates-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-australians/30-june-2021

- Australian Government. (2023). Closing the gap: Information repository. https://www.pc.gov.au/closing-the-gap-data/dashboard/se/outcome-area12/out-of-home-care#:~:text=Nationally%20in%202023%2C%2043.7%25%20of,points%20since%202019%20(figure%20SE12b

- Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. (2023). The stolen generations. https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/stolen-generations

- Australian Institute of Family Studies. (1993). The first Australians: Kinship, family and identity. https://aifs.gov.au/research/family-matters/no-35/first-australians-kinship-family-and-identity

- Awad G. H., Patall E. A., Rackley K. R., Reilly E. D. (2016). Recommendations for culturally sensitive research methods. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 26(3), 283–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/10474412.2015.1046600

- Bailey H. N., Moran G., Pederson D. R., Bento S. (2007). Understanding the transmission of attachment using variable-and relationship-centred approaches. Development and Psychopathology, 19(2), 313–343. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579407070162

- Bainbridge R., Tsey K., McCalman J., Kinchin I., Saunders V., Lui F. W., Cadet-James Y., Miller A., Lawson K. (2015). No one’s discussing the elephant in the room: Contemplating questions of research impact and benefit in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australian health research. BCM Public Health, 15, Article 696. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2052-3

- Beeghly M., Tronick E. (2011). Early resilience in the context of parent-infant relationships: A social development perspective. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care, 41(7), 197–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2011.02.005

- Boris N. W., Hinshaw-Fuselier S. S., Smyke A. T., Scheeringa M. S., Heller S. S., Zeanah C. H. (2004). Comparing criteria for attachment disorders: Establishing reliability and validity in high-risk samples. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(5), 568–577. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200405000-00010

- Bowlby J. (1988). A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. London.

- Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention Initiative. (2008). Domestic homicide in immigrant and refugee populations: Culturally-informed risk and safety strategies. https://anrows.intersearch.com.au/anrowsjspui/bitstream/1/18652/1/Brief_4-Online-Feb2018-linked-references.pdf

- Carlson V. J., Harwood R. L. (2003). Attachment, culture, and the caregiving system: The cultural patterning of everyday experiences among Anglo and Puerto Rican mother-infant pairs. Infant Mental Health Journal, 24(1), 53–73. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1002/imhj.10043

- Carriere J., Richardson C. (2009). From longing to belonging: Attachment theory, connectedness, and Indigenous children in Canada. In Brown I., McKay S., Fuchs D. (Eds.), Passion for action in child and family services: Voice from the Prairies (pp. 49–67). Canadian Plains Research Center.

- Cassidy J., Marvin R. S., & the MacArthur Attachment Working Group of the John D. and Catherine, T. MacArthur Network on the Transition from Infancy to Early Childhood. (1992). Attachment organization in preschool children: Procedures and coding manual [Unpublished Coding Manual]. Pennsylvania State University.

- Choate P. W., Kohler T., Cloete F., Crazybull B., Lindstrom D., Tatoulis P. (2019). Rethinking Racine v Woods from a decolonizing perspective: Challenging the applicability of attachment theory to indigenous families involved with child protection. Canadian Journal of Law and Society, 34(1), 55–78. https://doi.org/10.1017/cls.2019.8

- Cooke M., Mitrou F., Lawrence D., Guimond E., Beavon D. (2007). Indigenous well-being in four countries: An application of the UNDP’s human development index to Indigenous Peoples in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 7(1), Article 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-698X-7-9

- Copley J. A., Nelson A., Hill A. E., Castan C., McLaren C. F., Brodrick J., Quinlan T., White R. (2021). Reflecting on culturally responsive goal achievement with Indigenous clients using the Australian Therapy Outcome Measure for Indigenous Clients (ATOMIC). Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 68(5), 384–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12735

- Cowan P. A., Cowan C. P. (2007). Attachment theory: Seven unresolved issues and questions for future research. Research in Human Development, 4(3–4), 181–201. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1080/15427600701663007

- Crichlow W. (2002). Western colonization as disease: Native adoption and cultural genocide. Critical Social Work, 3(1), 1–14.

- Cyr C., Euser E. M., Bakermans-Kranenburg M. J., Van Ijzendoorn M. H. (2010). Attachment security and disorganisation in maltreating and high-risk families: A series of meta-analysis. Development and Psychology, 22(1), 87–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X221105250

- d’Agincourt-Canning L., Ziabakhsh S., Morgan J., Jinkerson-Brass E. S., Joolaee S., Smith T., Loft S., Rosalie D. (2024). Pathways: A guide for developing culturally safe and appropriate patient-reported outcomes (PROMs) and experience measures (PREMs) with Indigenous peoples. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 30(3), 418–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13947

- Dawson G., Ashman S. B., Hessl D., Spieker S., Frey K., Panagiotides H., Embry L. (2001). Autonomic and brain electrical activity in securely- and insecurely-attached infants of depressed mothers. Infant Behaviour & Development, 23, 135–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0163-6383(01)00075-3

- Dellaire D. H., Weinraub M. (2007). Infant-mother attachment security and children’s anxiety and aggression at first grade. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 28(5), 477–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2007.06.005

- Department of Children, Youth Justice and Multicultural Affairs. (2021, ). About child protection. https://www.cyjma.qld.gov.au/protecting-children/about-child-protection

- Department of Child Safety, Seniors and Disability Services. (2023, ). Family and child connect. https://www.dcssds.qld.gov.au/resources/dcsyw/about-us/funding-grants/specifications/facc-model-guidelines.pdf

- Enlow M. B., Egeland B., Carlson E., Blood E., Wright R. J. (2014). Mother-infant attachment and the intergenerational transmission of posttraumatic stress disorder. Development and Psychopathology, 26, 41–65. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000515

- First Nations Information Governance Centre. (2024). The First Nations principles of OCAP. https://fnigc.ca/ocap-training/

- Furman W., Collibee C. (2018). The past is present: Representations of parents, friends, and romantic partners predict subsequent romantic representations. Child Development, 89(1), 188–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12712

- Gaskins S., Beeghly M., Bard K. A., Gernhardt A., Liu C. H., Teti D. M., Thompson R. A., Weisner T. S., Yovsi R. D. (2017). Meaning and methods in the study and assessment of attachment. In Keller H., Bard K. A. (Eds.), The culture of attachment: Contextualising relationships and development (online ed., pp. 195–230). MIT Press Scholarship.

- George C., Main M., Kaplan N. (1985). Adult Attachment Interview (AAI). APA PsychTests. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/t02879-000

- Granot D., Mayseless O. (2001). Attachment security and adjustment to school in middle childhood. International Journal of Behavioural Development, 25(6), 530–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250042000366

- Harnett P. H., Featherstone G. (2020). The Role of decision making in the over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander children in the Australian child protection system. Children and Youth Services Review, 113, 105019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105019

- Healing Foundation. (2020). Improving the social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. https://healingfoundation.org.au/app/uploads/2020/07/Children_Report_Jun2020_FINAL.pdf

- Hofstede G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: Vol. 5. Cross-cultural research and methodology series. Sage.

- Hong Q. N., Fabregues S., Bartlett G., Boardman F., Cargo M., Dagenais P., Gagnon M., Griffiths F., Nicolau B., O’Cathain A., Rosseau M., Vedel I., Pluye P. (2018). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221

- Johnson-Jennings M., Billiot S., Walters K. (2020). Returning to our roots; Tribal health and wellness through land-based healing. Genealogy, 4(3), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4030091

- Jones H., Barber C. C., Nikora L. W., Middlemiss W. (2017). Māori child rearing and infant sleep practices. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 46(3), 30–37.

- Keller H. (2021). The myth of attachment theory (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003167099

- Kelley A., Belcourt-Dittloff A. B., Belcourt C., Belcourt G. (2013). Research ethics and Indigenous communities. American Journal of Public Health, 103(12), 2146–2152. https://doi.org/10.2105%2FAJPH.2013.301522

- Kerns K. A., Brumariu L. E., Seibert A. (2011). Multi-method assessment of mother-child attachment: Links to parenting and child depressive symptoms in middle childhood. Attachment & Human Development, 13(4), 315–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2011.584398

- Killikelly C., Maercker A. (2023). The cultural supplement: A new method for assessing culturally relevant prolonged grief disorder symptoms. Clinical Psychology in Europe, 5(1), Article e7655. https://doi.org/10.32872/cpe.7655

- Kline M. A., Shamsudheen R., Broesch T. (2018). Variation is the universal: Making cultural evolution work in developmental psychology. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological Sciences, 373(1743), 20170059. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0059

- Krakour J., Wise S., Connolly M. (2018). “We live and breathe through culture”: Conceptualising cultural connection for Indigenous Australian children in out-of-home care. Australian Social Work, 71(3), 265–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2018.1454485

- Lansdown R. G., Goldstein H., Shah P. M., Orley J. H., Di G., Kaul K. K., Kumar V., Laksanavicharn U., Reddy V. (1996). Culturally appropriate measures for monitoring child development at family and community level: A WHO collaborative study. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 74(3), 283–290.

- Lawler M. J., LaPlante K. D., Giger J. T., Norris D. S. (2012). Overrepresentation of Native American children in foster care: An independent construct? Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 21(2), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2012.647344

- Lindstedt S., Moeller-Saxone K., Black C., Herrman H., Szwarc J. (2017). Realist review of programs, policies, and interventions to enhance the social, emotional and spiritual well-being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people living in out-of-home-care. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 8(3), 1–30. http://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2017.8.3.5

- Listug-Lunde L., Vogeltanz-Holm N., Collins J. (2013). A cognitive-behavioural treatment for depression in rural American Indian middle school students. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 20(1), 16–34. https://doi.org/10.5820/aian.2001.2013.16

- Madigan S., Moran G., Pederson D. R. (2006). Unresolved states of mind, disorganised attachment relationships, and disrupted interactions of adolescent mothers and their infants. Developmental Psychology, 42(2), 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.293

- Main M., Solomon J. (1986). Discovery of an insecure-disorganised/disoriented attachment pattern. In Brazelton T. B., Yogman M. W. (Eds.), Affective development in infancy (pp. 95–124). Ablex Publishing Company.

- Malin M., Campbell K., Agius L. (1997). Raising children in the Nunga Aboriginal way. Family Matters, 43, 43–47.

- Manuela S., Sibley C. (2013). The Pacific Identity and Wellbeing Scale (PIWBS): A culturally-appropriate self-report measure for Pacific peoples in New Zealand. Social Indicators Research, 112(1), 83–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0041-9

- Masopustova Z., Tancos M., Fikrlova J., Lacinova L., Hanackova V. (2023). Infant attachment in the Czech Republic: Categorical and dimensional findings from a post-communist country. Infant Behaviour and Development, 71, 101835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2023.101835

- McLean S. (2016). Children’s attachment needs in the context of out-of-home care. Australian Institute of Family Studies. https://aifs.gov.au/sites/default/files/publication-documents/cfca-practice-attachment_0.pdf

- Meehan C. L., Quinlan R., Malcom C. D. (2013). Cooperative breeding and maternal energy expenditure among aka foragers. American Journal of Human Biology, 25(1), 42–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.22336

- Morelli G., Quinn N., Chaudhary N., Vicedo M., Rosabal-Coto M., Gottlieb A., Scheidecker G., Takada A. (2018). Ethical challenges of parenting interventions in low-to middle-income countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 49(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022117746241

- Neckoway R., Brownlee K., Castellan B. (2007). Is attachment theory consistent with Aboriginal parenting realities? First Peoples Child & Family Review, 3(2), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.7202/1069465ar

- Nielsen M., Haun D., Kärtner J., Legare C. H. (2017). The persistent sampling bias in development psychology: A call to action. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 162, 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2017.04.017

- Page M. J., McKenzie J. E., Bossuyt P. M., Boutron I., Hoffman T. C., Murlow C. D., Shamseer L., Tetzlaff J. M., Moher D. (2021). Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 134, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.003

- Pasco Fearon R. M., Belsky J. (2004). Attachment and attention: Protection in relation to gender and cumulative social-contextual adversity. Child Development, 75(6), 1677–1693. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00809.x

- Pastor D. L. (1981). The quality of mother-infant attachment and its relationship to toddlers’ initial sociability with peers. Developmental Psychology, 17(3), 326–335. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.17.3.326

- Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada. (1990). The Inuit way: A guide to Inuit culture.

- Rothbaum F., Weisz J., Pott M., Miyake K., Morelli G. (2000). Attachment and culture: Security in the United States and Japan. American Psychologist, 55(10), 1093–1104. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.10.1093

- Ryan F. (2011). Kanyininpa (holding): A way of nurturing children in Aboriginal Australia. Australian Social Work, 64(2), 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2011.581300

- Sagi A., van Ijzendoorn M. H., Aviezer O., Donnell F., Mayseless O. (1994). Sleeping out of home in a Kibbutz communal arrangement: It makes a difference for infant-mother attachment. Child Development, 65(4), 992–1004. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00797.x

- Scharfe E. (2017). Measurement: Categorical vs. continuous. In Shackelford T., Weekes-Shackelford V. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of evolutionary psychological science (pp. 1–4). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16999-6_1970-1

- Simpson J. A., Collins W. A., Trans S., Haydon K. C. (2007). Attachment and the experience and expression of emotions in romantic relationships: A developmental perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(2), 355–367. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.355

- Spieker S. J., Bensley L. (1994). Roles of living arrangements and grandmother social support in adolescent mothering and infant attachment. Developmental Psychology, 30(1), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.30.1.102

- Statistics Canada. (2022). Indigenous populations continues to grow and is much younger than the non-Indigenous population, although the pace has slowed. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/daily-quotidien/220921/dq220921a-eng.pdf?st=LZzBUiFL

- Stoval K. C., Dozier M. (2000). The development of attachment in new relationships: Single subject analysis for 10 foster infants. Development and Psychopathology, 12(2), 133–156. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1017/S0954579400002029

- Straus M. B. (2017). Treating trauma in adolescents: Development, attachment and the therapeutic relationship. Guildford Publications. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/bond/detail.action?docID=4769171

- Takahashi K. (1986). Examining the strange-situation procedure with Japanese mothers and 12-month-old infants. Development Psychology, 22(2), 265–270. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0012-1649.22.2.265

- Target M., Fonagy P., Shmueli-Goetz S. (2011). Attachment representations in school-age children: The development of the child attachment interview (CAI). Journal of Child Psychotherapy, 29(2), 171–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/0075417031000138433

- Thomas D. P., Bainbridge R., Tsey K. (2014). Changing discourse in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research, 1914-2014. Medical Journal of Australia, 201(1), 15–18. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja14.00114

- Tomlinson M., Cooper P., Murray L. (2005). The mother-infant relationship and infant attachment in a South African Peri-Urban settlement. Child Development, 76(5), 1044–1054. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00896.x

- True M. M., Pisani L., Oumar F. (2001). Infant-mother attachment among the Dogon of Mali. Child Development, 72(5), 1451–1466. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00359

- Ullrich J. S. (2019). For the love of our children: An Indigenous connectedness framework. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 15(2), 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180119828114

- Van Ijzendoorn M. H., Kroonenberg P. M. (1988). Cross-cultural patterns of attachment: A meta-analysis of the strange situation. Child Development, 59(1), 147–156. https://doi-org.ezproxy.bond.edu.au/10.2307/1130396

- Van Ijzendoorn M. H., Sagi-Schwartz A. (2008). Cross-cultural patterns of attachment: Universal and contextual dimensions. In Cassidy J., Shaver P. R. (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 880–905). Guildford Press.

- Warren S. L., Huston L., Egeland B., Sroufe L. A. (1997). Child and adolescent anxiety disorders and early attachment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(5), 637–644. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199705000-00014

- Waters E., Vaughn B. E., Egeland B. R. (1980). Individual differences in infant-mother attachment relationships at age one: Antecedents in neonatal behavior in an urban, economically disadvantaged sample. Child Development, 51(1), 208–216. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129608

- Weinfield N. S., Egeland B. (2004). Continuity, discontinuity, and coherence in attachment from infancy to late adolescence: Sequelae of organization and disorganization. Attachment & Human Development, 6(1), 73–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730310001659566

- Weinfield N. S., Sroufe L. A., Egeland B., Carlson E. (2008). Individual differences in infant-caregiver attachment. In Cassidy J., Shaver P. R (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 78–101). Guildford Press.

- Weinraub M., Bender R. H., Friedman S. L., Susman E. J., Knocke B., Bradley R., Houts E., Williams J. (2012). Patterns of developmental change in infants’ nighttime sleep awakenings from 6 through 36 months of age. Developmental Psychology, 48(6), 1511–1528. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027680

- Williams L. R., Turner P. R. (2020). Infant carrying as a tool to promote secure attachments in young mothers: Comparing intervention and control infants during the still-face paradigm. Infant Behaviour & Development, 58, 101413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2019.101413

- Yeo S. (2003). Bonding and attachment of Australian Aboriginal children. Child Abuse Review, 12(5), 292–304. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.817