INTRODUCTION

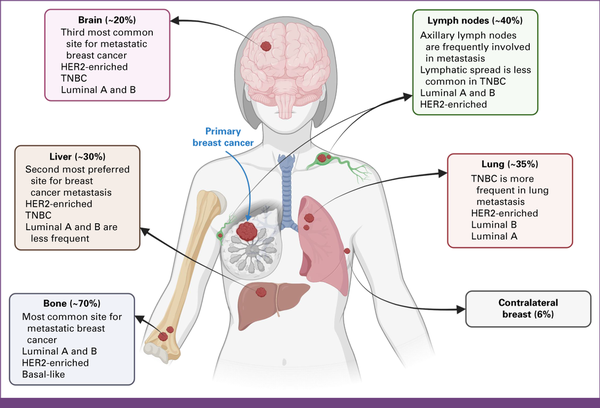

Breast cancer is a group of heterogeneous malignancies arising from the breast where the cancerous cells divide more rapidly than the healthy cells, evading immune response and/or apoptotic signals. It can spread from its primary site to different parts of the body by getting into the bloodstream or lymphatic system. A graphical representation of metastatic sites reported in breast cancer is shown in Figure 1.

FIG 1

Metastatic sites reported in breast cancer. The spread of breast cancer is dependent on molecular subtypes and the topology of the tumor. Nodal site's metastasis is frequented by axillary and clavicular lymph nodes. Metastasis is observed in locoregional to distant organs such as the lung, liver, bones, brain, etc. HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer. Created with BioRender.com.

According to GLOBOCAN 2022 estimates, breast cancer remains one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers worldwide. In India, breast cancer tops the female-centric cancers, representing nearly 27% of all cancers, as one of the most challenging health care maladies. The projections and cumulative risk for breast cancer are alarmingly high for India, requiring immediate attention. The proportion of highly aggressive triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) ranges from 6.7% to 27.9% in different countries, while some of the highest percentages are reported in India., Several of the TNBCs in the Indian population are associated with additional risk factors, such as early onset, lifestyle, obesity, substance abuse, family history, high mitotic indexes, and BRCA1/2 mutations.

With a large and diversified population spread across different geopolitical territories, India faces persistent obstacles to health equity. This becomes even more serious in oncology care, requiring persistent health care and palliative support. Besides health care, the economic burden in terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) losses is estimated to be around $11 billion in US dollars (USD), which was 0.4% of the country's GDP, in addition to years of potential productive life lost. In a recent study by Singh et al, the total cost of premature mortality was $5.6 billion (USD), representing 0.18% of GDP for head and neck cancer alone. Furthermore, among the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), the total cost of lost productivity because of premature cancer mortality in 2012 was $46.3 billion (USD), representing 0.33% of their combined GDP. With a budget of just 2%-3% of GDP, there are numerous challenges in delivering quality health care, especially in rural sectors that harbor nearly 900 million, or two thirds of India's population. Although the urban populations are exposed to unhealthy lifestyles and risk factors, the rural populations lack access to quality health care and trained professionals. These urban-rural disparities in sociodemographic, behavioral, and lifestyle-related factors add up to the cancer burden that India is facing now.

Notwithstanding the locoregionally present molecular heterogeneity, the treatment plans are determined by a multidisciplinary tumor board that considers pathologic parameters and TNM staging and grading. Management for early breast cancer in India follows standard global algorithms, taking theranostic biomarkers, tumor grade, predictive and prognostic parameters, and lymph node involvement into account. There is no consensus for advanced breast cancer treatment, which mainly deals with prolonging longevity with better life quality. In this comprehensive review, we focused on the breast cancer dynamics in India, the prevalence, pathophysiology, and two main aspects of breast cancer management: local treatment and systemic therapy. Our study is a reflective analysis of these present challenges in the context of breast cancer management in India and the lessons and learnings from these experiences.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

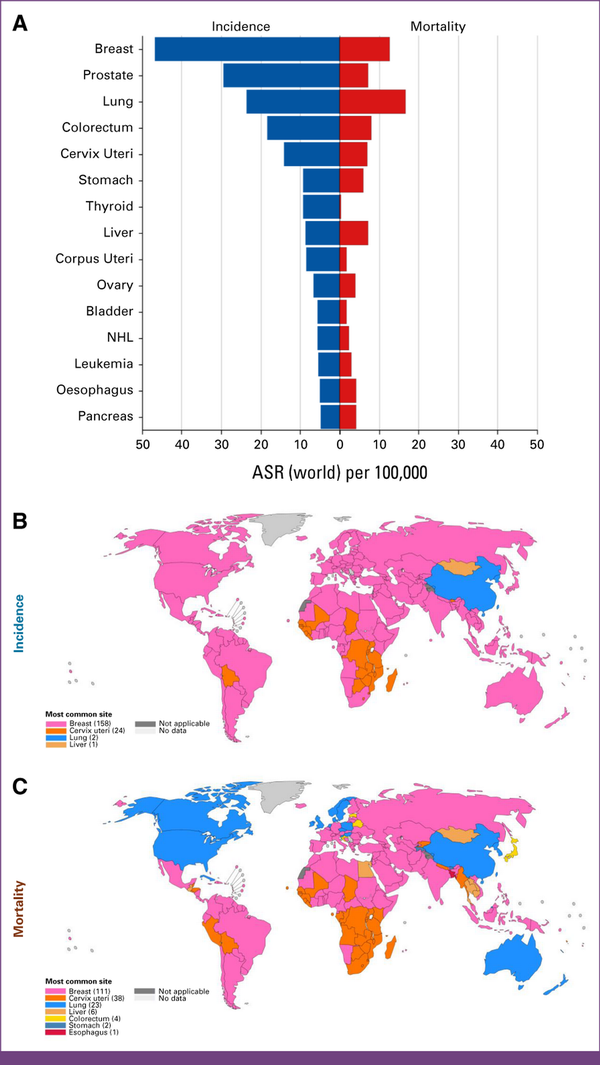

GLOBOCAN 2022 data indicate that with 2.3 million new cases, breast cancer is the second most common cancer globally, representing a quarter of all female cancer diagnoses. The widespread occurrence of breast cancer across sexes and age groups poses a significant public health challenge worldwide. It continues to be the leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women, with an estimated 666,103 deaths in 2022. Disparities in breast cancer incidence and mortality rates across countries, as influenced by the Human Development Index (HDI), highlight contrasting trends. Transitioning countries face a disproportionate burden of breast cancer deaths because of limited screening programs, delayed diagnosis, and inadequate access to quality care.

Although developed countries have reported a 40% decrease in age-standardized breast cancer mortality from 1980 to 2020, transitioning countries, lacking formal screening initiatives and sufficient health care infrastructure, continue to experience higher breast cancer–related mortality rates. By 2050, global breast cancer incidence is projected to exceed three million cases, of which transitioning nations with low HDI are anticipated to bear a disproportionately higher burden. This projected escalation is especially pronounced in countries with low and medium foreign direct investment, which are home to most of the world's population.

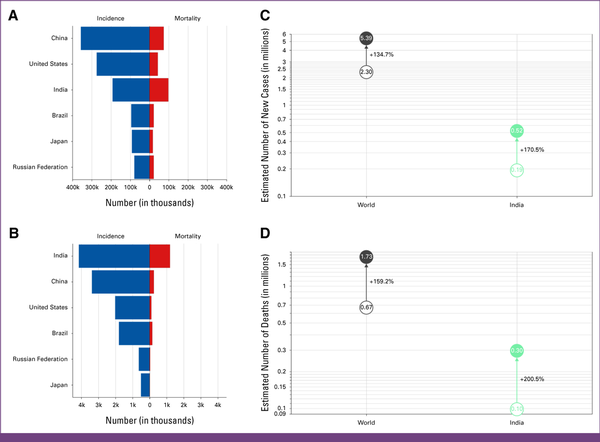

As per GLOBOCAN 2022 statistics, breast cancer stands out as the most prevalent malignancy across sexes in India. Despite ranking third globally in incidence (192,020 cases), India leads in mortality, with 98,337 deaths in 2022. The incidence and mortality rates among younger females (≤29 years) are notably high in India, aggravating concerns for health care. Furthermore, projections for 2050 indicate a significant increase in breast cancer incidence (519,507 at 170.5%) and mortality (295,473 at 200.5%). These increments are disproportionately high compared with global incidence and mortality rates of 134.7% and 159.2%, respectively. Several factors appear to contribute to this transition, noticeably, enhanced pollution, infection, hypertension, obesity, diabetes, and depression. Lifestyle changes, socioeconomic disparities, and consumption of tobacco and alcohol further aggravate the cause. Inadequate health care screening programs and a lack of social and community awareness are slowly turning India into the cancer capital of the world.

Data from the National Cancer Registry Programme by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) reveal significant disparities in breast cancer incidences between rural and urban populations, with an occurrence of five per 100,000 cases in the rural areas, compared with 30 per 100,000 cases in the urban regions. This inequality is more pronounced in urban metro cities and the northeastern regions of India. Gynecologic cancers, predominantly breast cancer, constitute half of all female cancers, according to the ICMR-National Centre for Disease Informatics and Research hospital-based cancer registries report in 2021. The GLOBOCAN 2022 statistics for the world and India are displayed in Appendix Figures A1 and A2, respectively.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

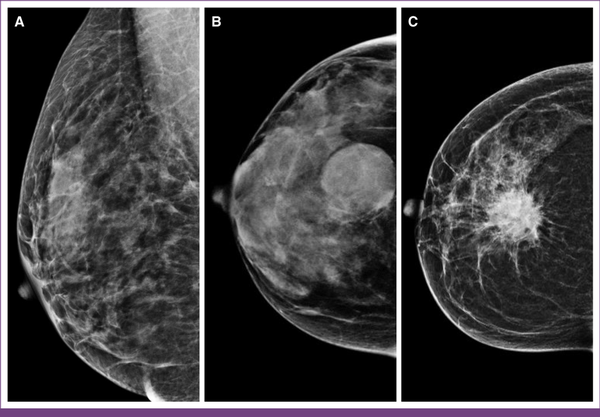

A majority of early-stage breast cancers appear asymptomatic; even large tumors may present as a painless mass. In countries with established early screening facilities, mammograms evolved as one of the most effective tools for detecting early-stage breast cancers and microcalcifications, even when these are too small to be felt and detected. Late-stage presentation is common in transitioning countries., Varying heterogeneity and stages of cancer lead to diverse symptoms among the patients. Non–lump-presenting symptoms are usually associated with prolonged presentation. Immediate health care interventions and diagnosis are a prerequisite for further treatments. Figure 2 presents mammograms from normal, benign, and malignant breasts.

FIG 2

Mammographic appearance of normal, benign, and malignant breast lesions. (A) Normal breast with uniform nondense tissue. (B) Benign lesion having a round mass with circumscribed margins. (C) Malignant lesion characterized by a high-density mass with spiculated margins, indicative of invasive breast cancer.

BREAST CANCER PRESENTATION IN INDIA: SOCIOCULTURAL BARRIERS, SCREENING, AND POLICY INITIATIVES

There is a general lack of awareness about breast cancer and the importance of early detection in India, which is further compounded by insufficient public health campaigns to educate women about self-breast examinations and screening. Factored by its large population, social stigma and regional beliefs often hinder early screening, detection, and intervention. Timely diagnosis of the disease through clinical breast examinations (CBE) or mammography improves the chances of successful treatment and substantially elongates the probability of survival. Nationwide multidisease screening in India includes CBE, oral examinations, and cervical checkups. High treatment costs and a shortage of community health centers further delay diagnosis and treatment. Because early-stage signs such as lumps, dimpling, or skin changes are painless, most cases present with advanced cancer or distant metastasis.,

India's complex geography exacerbates the problem, with many areas lacking adequate health care facilities, infrastructure, and trained personnel to conduct screenings. Conservative social norms often make women's health a taboo subject., Cultural stigma, child marriage, and gender inequality associated with cancer prevent women from seeking early screening and adopting prophylactic measures. In a patriarchal rural setup, women's health is usually not prioritized, and they often lack the autonomy to seek medical care without previous consent from male family members., A comprehensive audit of over 1,300 patients with breast cancer from our group reported a delayed symptomatic presentation with larger tumor size and metastasis in 15% of patients. One cross-sectional study found that over 50% of cases presented at an advanced stage, predominantly in socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, indicating a link between poverty, awareness, and adverse outcomes. This is consistent with the findings of Chen et al that poverty is associated with poor tumor characteristics and increased mortality.

To realize the goal of universal health coverage, the government of India has started Ayushman Bharat, a flagship program, as advised by the National Health Policy 2017. However, its implementation at a nationwide scale seems challenging. The Breast Cancer (Awareness) Bill, 2022, was introduced in India, aiming to address the growing incidence of breast cancer through public health interventions. The bill focuses on promoting awareness, early detection, and timely treatment of breast cancer, particularly among underserved and rural populations. It advocates for nationwide screening programs, increased accessibility to mammography and diagnostic services, and mandatory inclusion of breast cancer education in public health campaigns. The legislation emphasizes reducing stigma and encouraging self-breast examinations, while also calling for improved government support for treatment, research, and health care infrastructure to combat the disease effectively. The National Health Mission has expanded the National Programme for Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases (NCD) by establishing new clinics and centers for early detection and management. The Ayushman Bharat initiative includes a nationwide NCD and cancer screening program for adults. The government provides technical and financial support to train health care professionals; by May 2024, over 1.4 million primary health care providers had been trained in NCD screening, health promotion, and early detection.

The Cancer Moonshot Initiative, a collaboration between the United States, Australia, India, and Japan, aims to combat cancer in the Indo-Pacific region, focusing on cervical and other cancers. India has pledged to share digital health expertise through its NCD portal and committed $10 million (USD) to the WHO's global digital health initiative in the Indo-Pacific. The Quad Cancer Moonshot seeks to improve cancer care infrastructure, expand research partnerships, develop data systems, and enhance support for cancer prevention, early detection, treatment, and care.

In addition to government efforts, public-private partnerships and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are contributing to breast cancer awareness and treatment. The Pink Project, a collaboration between the Government of Punjab, Roche Pharma India, and Niramai Health Analytix Private Limited, promotes early intervention, diagnosis, and treatment., NGOs are also playing a key role in grassroots awareness, offering self-breast examination training and deploying mobile mammography units to increase access to screening services, particularly in remote regions where health care facilities are scarce.,

PROGNOSIS AND RISK ASSESSMENT

Prognostic markers, which indicate disease progression, influence treatment and follow-up care. Widely used prognostic factors in breast cancers include age, tumor histology, stage, grade, hormone receptor (HR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status, proliferation markers, regional lymph nodes, and several multigene panel assays. In Indian settings, classical prognostic markers include age, grade, lymph node involvement, and HR and HER2 status. Hormone receptor and HER2 are validated predictive biomarkers for endocrine or HER2-targeted therapies, respectively. Although early-stage detection of breast cancer has constantly improved prognosis as per the global standards, the presence of theranostic biomarkers opens up opportunities for additional targets. In Indian patients with breast cancer, four major subtypes (luminal A, luminal B, HER2-enriched, and TNBC) are taken into clinical relevance to decide treatment modalities. There are several concerns regarding gene expression tests in India, stemming from aggressive malignancies, insufficient gene recurrence score data, and exorbitantly high costs of such tests. Risk calculators and clinical predictors are rather preferred over molecular tests by Indian oncologists.Table 1 underscores the validated biomarkers for treatment planning in the Indian setup.

TABLE 1

Validated Biomarkers for Treatment Planning and Execution

| Biomarker | Testing Method | Expression Recommendations | Applications | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER | IHC | Positive if ≥1% express it | Determines Luminal type classification Better prognostic biomarker | Endocrine treatment |

| PR | IHC | Positive if ≥1% express it | Determines Luminal type classification Better prognostic biomarker | Endocrine treatment |

| HER2 | IHC or ISH | IHC 3+ or 2+ and ISH-amplified | Characterization of HER2-enriched subtype Prognostic biomarker | HER2-targeted therapies |

| Ki67 | IHC | The consensus cutoff for a high Ki-67 labeling index is 20% | Determines Luminal A and Luminal B subtypes Prognostic marker in Luminal type tumors Predictive marker of response to neoadjuvant CT and endocrine therapy | Chemotherapy in high Ki-67 expression |

| Molecular subtypes | IHC and gene expression profiles | Combination of HR, HER2, and Ki67 | Prognostic potential depending on subtypes Predictive response to systematic therapies | Different algorithms of systematic therapies |

| Gene expression tests (MammaPrint, Oncotype Dx, Prosigna) | Gene expression profiles, N-Counter technology, qRT-PCR | Validated in several clinical trials (retrospectively and prospectively) | Prognostic marker in Luminal type tumors with ≤3 lymph nodes | Chemotherapy for high-risk/score |

| BRCA mutations | NGS on PBMCs or tumor specimens | Sequencing validations by PCR | Predictive marker for PARP inhibitors Determines familiality of cancer | PARP inhibitors in advanced breast cancer |

| PD-L1 | IHC | Positive if ≥1% of tumors express it | Predictive for immunotherapy | Immunotherapy |

MANAGEMENT

Clinical management of breast cancer involves a comprehensive approach to determining treatment options depending on the diagnostic reports, stage, grade, receptor positivity, etc. The aim of early breast cancer management includes the removal of tumors from the breast and lymph nodes, thus effectively halting metastatic recurrence. Treatment goals for locally advanced and metastatic breast cancer (MBC) are to prolong survival and palliation with improved quality of life. Although there is negligible scope for cure, patients with MBC ultimately succumb to death due to metastases, with a median overall survival (OS) of about 3 years. Our group on MBC reported a poor median progression-free survival (PFS) of 14.2 months and OS of 31.7 months for MBC, lower than in transitioned countries. In this work, we documented that 22% of patients presented with upfront metastasis, substantially higher than reported from Western studies (3%-8%)., Nevertheless, a multidisciplinary approach is crucial to balance systemic and locoregional treatments, reducing the risk of death from distant metastasis.

LOCAL TREATMENT

Surgery

Surgery, a cornerstone of breast cancer treatment, particularly for early-stage disease, involves managing the primary tumor and the axilla. The primary tumor can be removed via lumpectomy or mastectomy, guided by tumor size, diagnostic parameters, comorbidities, and patient preferences.

Breast-Conserving Surgery

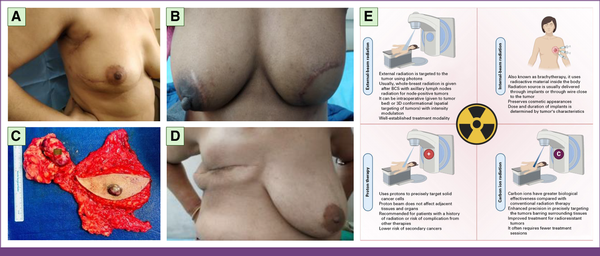

The breast-conserving surgery (BCS) offers patients the option to retain their breasts without compromising treatment effectiveness. It involves removing the tumor with clear surgical margins, yielding acceptable cosmetic outcomes, followed by adjuvant radiation therapy. Landmark studies have shifted the approach from radical mastectomy to BCS, evidenced by the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-06 trial, which reported no difference in survival outcomes in lumpectomy with radiation compared with radical mastectomy for women with tumors ≤4 cm., Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) can enable BCS for patients who might not otherwise be candidates, including those in the second or third trimester of pregnancy. For patients with large operable breast cancers, NACT can reduce tumor size sufficiently to make BCS a viable option. Additionally, obtaining a specimen mammogram after successful excision ensures the completeness of resection (Fig 3A). In recent times, efforts have been made to improve the cosmetic outcome after BCS using oncoplastic techniques (Fig 3B).

FIG 3

Local management of breast cancer through surgery and radiation. Postoperative photographs of patients who underwent (A) right wide local excision and ALND, and (B) BCS with muscle-sparing latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction. (C) Specimen of MRM. (D) MRM and (E) radiation therapy modalities used in breast cancer treatment, including external-beam and brachytherapy approaches. ALND, Axillary Lymph Node Dissection; BCS, breast-conserving surgery; MRM, modified radical mastectomy. Panel E is Created with BioRender.com.

Mastectomy

Mastectomy is performed when BCS is contraindicated or at the patient's preference, and prophylactically in patients with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndromes (eg, BRCA1/2 mutations). Modern breast surgery uses modified radical mastectomy (MRM), simple (total) mastectomy, and in more recent times, skin-sparing mastectomy (SSM) and nipple-areolar–sparing mastectomy (NSM). Simple mastectomy entails the complete removal of the entire breast and the underlying fascia of the pectoralis major muscle. In MRM, the level I and II axillary lymph nodes are additionally removed (Figs 3C and 3D). In SSM and NSM, the natural breast skin envelope and nipple-areola complex are preserved, respectively. In properly selected patients, these have been shown to provide similar oncologic outcomes compared with more mutilating surgeries.,

Axillary Management

The traditional management of the axilla has been axillary lymph node dissection (ALND), which entails the removal of level I and II axillary lymph nodes. Although ALND results in low regional recurrence rates (1%-2%), it is associated with significant morbidities such as lymphedema, paresthesia, arm stiffness, and restricted range of motion. Several randomized prospective trials have shown that short- and long-term morbidity is reduced with sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) compared with ALND. SLNB is the standard of care for clinically node-negative breast cancer, providing staging information to guide adjuvant therapy and potentially offering therapeutic benefits. Recent studies suggest that axillary management can be avoided in certain patient populations. The SOUND trial reported that omitting axillary surgery was as effective as SLNB in small breast cancers (≤2 cm) with negative preoperative axillary ultrasonography, without affecting survival.

Radiotherapy

Radiation therapy offers treatment with high-energy X-rays and other forms of radiation to destroy cancer cells. Postoperative radiation therapy (PRT) after BCS or mastectomy is used to reduce the risk of cancer recurrence. PRT, using external-beam or brachytherapy, improves disease-free survival (DFS) and OS in lymph node–positive patients undergoing BCS and reduces 5-year local recurrence and decline in the 15-year mortality risk, irrespective of systemic therapy. Newer radiotherapy methods involving proton and carbon ions are gaining prominence because of precision in targeting tumors and minimal radiation dosage. Figure 3 illustrates local therapies involved in breast cancer.

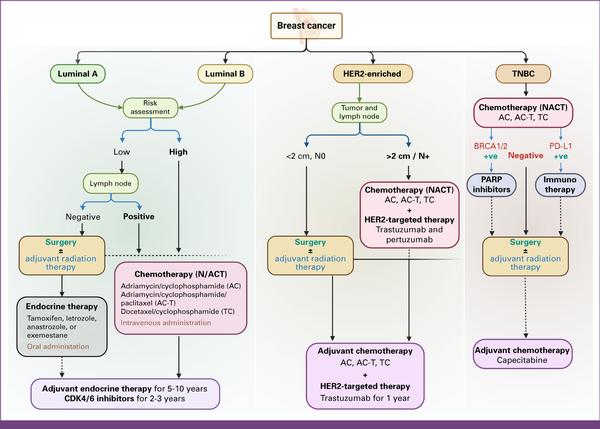

SYSTEMIC TREATMENT

Most women with breast cancer require systemic therapy, as outlined in Figure 4, which can be administered before (neoadjuvant) or after surgery (adjuvant). Systemic therapy has shown promising results, reducing breast cancer mortality by one third., Molecular classification of breast cancer and risk assessment through multigene assays is discouraged in resource-limited countries such as India. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is the mainstay for determining subtypes and proliferation through the Ki-67 labeling index. However, borderline or intermediate positivity of Ki-67 poses challenges in the further delineation of breast tumors. Still, with an indication of IHC for theranostic biomarkers and risk assessment of tumor grade, proliferation, lymph node involvement, etc, systemic therapy is administered.

FIG 4

Subtype-specific management algorithm for breast cancer. Luminal subtypes with a lower risk of recurrence and N0 status are usually given upfront surgery followed by endocrine therapy alone. For high-risk and/or N+ categories, chemotherapy is given in neoadjuvant settings. HER2-enriched and TNBC categories are recommended for NACT, followed by local therapy and subsequent adjuvant chemotherapy. The algorithm may vary as per the clinicopathologic requirements. HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; NACT, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; PARP, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer. Created with BioRender.com.

Endocrine Therapy

It is used for luminal breast cancer whose growth is dependent on estrogen. The menopausal status of the female determines the endocrine agent. One such drug, tamoxifen, reduces the risk of recurrence in premenopausal women with estrogen receptor–positive tumors irrespective of age, node, or chemotherapy used. Aromatase inhibitors (AIs), along with tamoxifen, are recommended therapeutic choices for postmenopausal women as upfront or sequential therapy. AIs have shown significant prolongation of DFS but not mortality., Adjuvant endocrine therapy is recommended over 5-10 years in HR-positive cases, with careful consideration of potential impact and tolerability beyond 5 years.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy, the standard of care for patients with a high risk of recurrence, involves the use of drugs to target and destroy rapidly dividing cancer cells. Chemotherapeutic interventions are determined by several clinicopathologic parameters such as locoregional tumor burden, molecular subtype, lymph node involvement, along with other complications, comorbidities, and potential survival parameters. It is the key systemic therapy with proven effectiveness against TNBC and complements endocrine and HER2-targeted treatments in luminal-type and HER2-enriched subtypes, respectively. Standard chemotherapy in TNBC is preferably given in a neoadjuvant setting with pathologic complete response (pCR) at the time of surgical intervention, exhibiting a highly favorable prognosis.

HER2-Targeted Therapy

Administered in HER2-positive cases, trastuzumab is a monoclonal antibody (mAb) directed toward the extracellular domain of HER2, effectively impeding cancer growth. Pertuzumab is another mAb targeting the dimerization domain of the HER2 protein. Concurrent to NACT, HER2-targeted therapy has been the standard of care for HER2-enriched tumors irrespective of luminal status and has achieved pCR with improved DFS and OS., For patients with ≤pT1 and N0 tumors, single-agent trastuzumab is recommended for 1 year, as no additional benefit was conferred beyond 1 year of trastuzumab administration. Patients having advanced disease (≥pT2 and N+) are recommended for dual HER2 blockade (trastuzumab and pertuzumab) to further reduce the risk of recurrence and improve DFS.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapeutic drugs aid the immune system in recognizing and attacking cancer cells, and have shown promising results. It has emerged as an encouraging approach in the treatment of breast cancer, particularly in TNBC subtypes with limited therapeutic options. PD-L1 inhibitor atezolizumab combined with nab-paclitaxel has shown better PFS in a phase 3 trial. Pembrolizumab (anti–PD-1) is another antibody recently Food and Drug Administration–approved for stage III-IVA cervical, gastric, metastatic biliary tract, and non–small cell lung cancers. Findings of the KEYNOTE-355 trial suggest that pembrolizumab along with chemotherapy significantly increased OS among patients with advanced TNBC expressing PD-L1. Such promising findings open new avenues for combining immunotherapy with chemotherapy to improve metastatic TNBC management.

FOLLOW-UP CARE AND PERSONALIZED MEDICINE

Breast cancer care and management increasingly emphasize patient outcomes, treatment-associated toxicities, and quality of life. Primary care providers offer psychosocial assistance and supportive services throughout the treatment course to improve quality of life. While managing follow-up patients for locoregional recurrence or therapy-related complications, it is equally important to address psychological concerns, provide rehabilitation services, and provide palliative care to optimize outcomes. Such psychosocial counseling and frequent follow-up are necessary not only to motivate patients to continue adjuvant therapies but also to empower them holistically throughout the cancer continuum. With the increase in per-capita income and GDP of transitioning countries, there is an expanding demand for personalized medicine in clinical oncology, catering to individuals' unique genetic and environmental factors. Besides traditional theranostic biomarkers, surrogate tumor phenotypes are emerging for treatment customization. With the advancement of molecular signature panels such as MammaPrint, Oncotype Dx, and Prosigna, there lies enormous scope for personalized medicine in improving breast cancer outcomes.

SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC FACTORS IN TREATING BREAST CANCER IN INDIA

India's diverse sociocultural, linguistic, and religious landscape influences disease presentation. Breast cancer screening in India remains negligible, mainly because of pervasive social taboos preventing women from seeking medical assistance. Cancer screening programs face challenges related to infrastructure, awareness, and resources. Population-based cancer registries report significant geographic disparities in breast cancer incidence, with urban and metro cities burdened with the disease., Screening studies indicate greater breast examination coverage among wealthier groups. Advanced-stage breast cancer is associated with lower education levels. Women with financial stability, higher education, and urban residence have better access to screening and diagnosis. Oncology care disparities are significant in India's northeastern states because of diverse geographical terrain, customs, cultures, food habits, and ethnicities, contributing to the highest cancer incidence rates in India. Aizawl, Mizoram, and the Papum Pare district of Arunachal Pradesh have the highest age-adjusted incidence rates for males and females, compared with the national average.

Various governmental and nongovernmental organizations that provide crucial support in breast cancer care, advocate policies, and provide treatment funds are working on awareness campaigns, early detection programs, and improving treatment facilities. Medical research and advancements in breast cancer treatment are ongoing in India. Integrating personalized medicine, targeted therapies, and immunotherapy are being explored to improve outcomes. This is encouraging for government authorities to ensure further sufficient awareness programs and screening opportunities, particularly for socioeconomically marginalized populations, for the necessary implementation and further compliance.

In conclusion, the clinical management of patients with breast cancer in India is evolving with advances in tumor biology. With the global breast cancer burden projected to increase to 5.4 million by 2050, India will be a major contributor. There is an urgent need for widespread screening and awareness programs at the community level. The optimal screening method for India is debatable, given its large population and limited affordable health care. However, it is essential to reach underprivileged and underserved communities, who represent the majority of the disease burden. The current number of population-based and hospital-based cancer registries in India is vastly underrepresented, with just 38 population-based cancer registries and 304 hospital-based cancer registries. Rigorous quality assurance measures for data collection, storage, and usage are also needed to ensure data reliability. Additionally, the long delays in updating registries (2-3 years in India, compared with 12-30 months in the United States) need to be addressed. Another issue is the blind adoption of Western guidelines, gene panels, treatment plans, and risk assessments, rather than developing India-specific approaches.

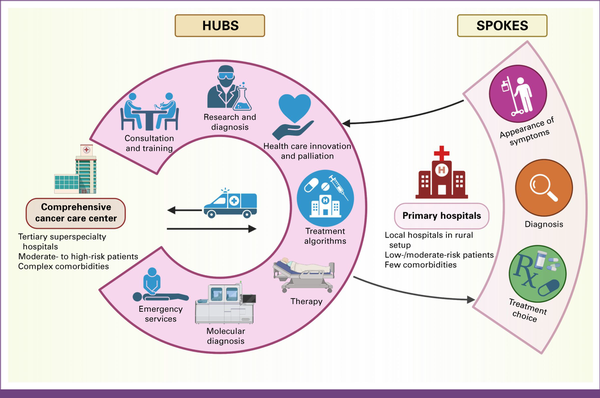

Given that 75% of the population live in rural areas, India should adopt a hub-and-spoke model as illustrated in Figure 5. Establishing a network of primary health care facilities (spokes) in remote areas, with referral arrangements to well-equipped central facilities (hubs), can bridge the gap between populations separated by socioeconomic disparities. This model extends specialized cancer care beyond urban centers, providing comprehensive care and capacity-building in rural areas. The cancer management in India must focus not only on treatment but also on the combination of prevention and early detection, promoting a balanced lifestyle, and coordination between the hub and spoke centers, for management as well as long-term research.

FIG 5

Hubs-and-spokes model of cancer treatment. Comprehensive cancer care centers (hubs) provide advanced diagnostics, specialized oncologists, and multidisciplinary treatment. Primary hospitals (spokes) perform initial screenings, diagnoses, and basic treatments. Patients are referred to hubs for complex care. This coordinated system improves cancer outcomes, optimizes resources, and ensures equitable access to high-quality care across regions. Created with BioRender.com.

As this model evolves, policymakers and stakeholders must invest in infrastructure and training for health care professionals in rural areas. The hub-and-spoke model can ensure that quality health care is accessible to individuals in remote and underserved areas. None of this is possible unless all stakeholders, including providers, payers, regulators, and accreditors, change their mindsets and start accepting patient journeys that are not confined to a single location or only to physical spaces. The future belongs to players who provide long-term seamless patient journeys through physical and digital omnichannel health care systems.

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

All data and materials used in this review are publicly available and have been appropriately cited within the article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Tryambak Pratap Srivastava, Ajay Gogia, Sukhda Monga, Joyeeta Talukdar, Ruby Dhar, Subhradip Karmakar

Administrative support: Ruby Dhar, Subhradip Karmakar

Provision of study materials or patients: Rajinder Parshad, Sukhda Monga, Joyeeta Talukdar, Avdhesh Rai, Ruby Dhar

Collection and assembly of data: Tryambak Pratap Srivastava, Rajinder Parshad, Sukhda Monga, Joyeeta Talukdar, Avdhesh Rai

Data analysis and interpretation: Tryambak Pratap Srivastava, Isha Goel, Rajinder Parshad, Joyeeta Talukdar, Avdhesh Rai, Ruby Dhar

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/go/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

No potential conflicts of interest were reported.

APPENDIX

FIG A1

GLOBOCAN 2022 statistics. (A) Age-standardized rates (world) per 100,000 cancers worldwide. The most common site per country is absolute numbers (ASR [world]), females in 2022, and (B) incidence and (C) mortality. ASR, age-standardized rate; NHL, non-hodgkin lymphoma.

FIG A2

GLOBOCAN 2022 statistics for India. Absolute numbers, incidence, and mortality, both sexes, in 2022, for (A) age (0-85+ years), and (B) age (0-29 years). Estimated number of cases from 2022 to 2050, both sexes, age (0-85+ years): (C) incidence, and (D) mortality.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are grateful to AIIMS, New Delhi, for the institutional and logistical support for this study. The authors offer their sincere thanks to Dr Sanjay Thulkar and Dr Krithika Rangarajan for providing the breast mammograms. Finally, the authors would like to acknowledge BioRender for their image preparation tool.

REFERENCES

1.

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al.: Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 74:229-263, 20242.

Sandhu GS, Erqou S, Patterson H, et al.: Prevalence of triple-negative breast cancer in India: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Oncol 2:412-421, 20163.

Kulkarni A, Kelkar DA, Parikh N, et al.: Meta-analysis of prevalence of triple-negative breast cancer and its clinical features at incidence in Indian patients with breast cancer. JCO Glob Oncol 6:1052-1062, 20204.

Thakur KK, Bordoloi D, Kunnumakkara AB: Alarming burden of triple-negative breast cancer in India. Clin Breast Cancer 18:e393-e399, 20185.

Chakraborty S: Making quality cancer care more accessible and affordable in India. https://www.ey.com/content/dam/ey-unified-site/ey-com/en-in/insights/health/documents/ey-making-quality-cancer-care-more-accessible-and-affordable-in-india.pdf6.

Singh A, Sullivan R, Bavaskar M, et al.: A prospective health economic evaluation to determine the productivity loss due to premature mortality from oral cancer in India. Head Neck 46:1263-1269, 20247.

Pearce A, Sharp L, Hanly P, et al.: Productivity losses due to premature mortality from cancer in Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS): A population-based comparison. Cancer Epidemiol 53:27-34, 20188.

Khanna D, Sharma P, Budukh A, et al.: Rural-urban disparity in cancer burden and care: Findings from an Indian cancer registry. BMC Cancer 24:308, 20249.

Harbeck N, Gnant M: Breast cancer. Lancet 389:1134-1150, 201710.

Arnold M, Morgan E, Rumgay H, et al.: Current and future burden of breast cancer: Global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast 66:15-23, 202211.

World Health Organization: Breast Cancer. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer12.

Mathur P, Nandakumar A, Fitzmaurice C, et al.: The burden of cancers and their variations across the states of India: The global burden of disease study 1990–2016. Lancet Oncol 19:1289-1306, 201813.

National Centre for Disease Informatics and Research, National Cancer Registry Programe, Indian Council of Medical Research: Three Year Report of PBCR 2012-2014. https://www.icmr.gov.in/icmrobject/static/icmr/dist/images/pdf/reports/Preliminary_Pages_Printed1.pdf14.

Indian Council of Medical Research, Clinicopathological Profile of Cancers in India: A Report of the Hospital Based Cancer Registries 2021. https://ncdirindia.org/All_Reports/HBCR_2021/15.

Esserman LJ, Shieh Y, Rutgers EJT, et al.: Impact of mammographic screening on the detection of good and poor prognosis breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat 130:725-734, 201116.

Gogia A, Deo SVS, Sharma D, et al.: Clinicopathologic characteristics and treatment outcomes of patients with up-front metastatic breast cancer: Single-center experience in India. J Glob Oncol 5:1-9, 201917.

Koo MM, von Wagner C, Abel GA, et al.: Typical and atypical presenting symptoms of breast cancer and their associations with diagnostic intervals: Evidence from a national audit of cancer diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiol 48:140-146, 201718.

Sawhney R, Nathani P, Patil P, et al.: Recognising socio-cultural barriers while seeking early detection services for breast cancer: A study from a Universal Health Coverage setting in India. BMC Cancer 23:881, 202319.

Hanrahan EO, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Giordano SH, et al.: Overall survival and cause-specific mortality of patients with stage T1a,bN0M0 breast carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 25:4952-4960, 200720.

Gupta A, Shridhar K, Dhillon PK: A review of breast cancer awareness among women in India: Cancer literate or awareness deficit? Eur J Cancer 51:2058-2066, 201521.

Takkar N, Kochhar S, Garg P, et al.: Screening methods (clinical breast examination and mammography) to detect breast cancer in women aged 40–49 years. J Midlife Health 8:2-10, 201722.

Sharma K, Costas A, Shulman LN, et al.: A systematic review of barriers to breast cancer care in developing countries resulting in delayed patient presentation. J Oncol 2012:121873, 201223.

Kumar A, Bhagabaty SM, Tripathy JP, et al.: Delays in diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer and the pathways of care: A mixed methods study from a tertiary cancer centre in North East India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 20:3711-3721, 201924.

Garg S, Anand T: Menstruation related myths in India: Strategies for combating it. J Fam Med Prim Care 4:184-186, 201525.

Access to Health Care Difficult for Most Indian Women—DW—08/21/2019. https://www.dw.com/en/access-to-health-care-a-distant-dream-for-most-indian-women/a-5010851226.

Das M, Angeli F, Krumeich AJSM, et al.: The gendered experience with respect to health-seeking behaviour in an urban slum of Kolkata, India. Int J Equity Health 17:24, 201827.

Indiaspend.com LG: 80% Indian women need permission to visit health centre, 5% have sole control over choice of husband. Scroll.in. 2017. https://scroll.in/article/829205/80-indian-women-need-permission-to-visit-health-centre-5-have-sole-control-over-choice-of-husband28.

Suhani S, Kazi M, Parshad R, et al.: An audit of over 1000 breast cancer patients from a tertiary care center of Northern India. Breast Dis 39:91-99, 202029.

Ali R, Mathew A, Rajan B: Effects of socio-economic and demographic factors in delayed reporting and late-stage presentation among patients with breast cancer in a major cancer hospital in South India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 9:703-707, 200830.

Chen JC, Handley D, Elsaid MI, et al.: Persistent neighborhood poverty and breast cancer outcomes. JAMA Netw Open 7:e2427755, 202431.

National Health Authority: About Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY). https://nha.gov.in/PM-JAY32.

Sumathy DT, Thangapandian T: The breast cancer (awareness) bill. 2022. https://www.sansad.in/getFile/BillsTexts/LSBillTexts/Asintroduced/103%20OF%202022%20AS.pdf?source=legislation33.

Ministry of Health & Family Welfare: Status of the Action Plan for Cancer Screening in Rural Areas. https://www.mohfw.gov.in/?q=en/pressrelease-434.

Fact Sheet: Quad Countries Launch Cancer Moonshot Initiative to Reduce the Burden of Cancer in the Indo-Pacific. Government of India. https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/38326/Fact_Sheet_Quad_Countries_Launch_Cancer_Moonshot_Initiative_to_Reduce_the_Burden_of_Cancer_in_the_IndoPacific35.

Roche, Pink Project: Fostering early detection to reduce breast cancer burden in the society. https://www.rocheindia.com/stories/pink-project36.

Financial Express: Govt of Punjab, Roche Pharma India and Niramai Health Analytix partner to accelerate breast cancer management. 2022. https://www.financialexpress.com/business/healthcare-govt-of-punjab-roche-pharma-india-and-niramai-health-analytix-partner-to-accelerate-breast-cancer-management-2481042/37.

PTI: Xiaomi partners with Yuvraj Singh’s foundation to launch breast cancer screening initiative. Deccan Herald. https://www.deccanherald.com/india/xiaomi-partners-with-yuvraj-singhs-foundation-to-launch-breast-cancer-screening-initiative-308027238.

Mammography Van—Club. https://rotaryclubgurgaon.com/mammography-van/39.

American Cancer Society: Breast Cancer, Breast Cancer Information & Overview. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer.html40.

Simpson JF, Gray R, Dressler LG, et al.: Prognostic value of histologic grade and proliferative activity in axillary node-positive breast cancer: Results from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Companion Study, EST 4189. J Clin Oncol 18:2059-2069, 200041.

Senkus E, Kyriakides S, Ohno S, et al.: Primary breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 26:v8-v30, 201542.

Batra A, Patel A, Gupta VG, et al.: Oncotype DX: Where does it stand in India? J Glob Oncol 5:1-2, 201943.

Cardoso F, Paluch-Shimon S, Senkus E, et al.: 5th ESO-ESMO international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC 5). Ann Oncol 31:1623-1649, 202044.

Iqbal J, Ginsburg O, Rochon PA, et al.: Differences in breast cancer stage at diagnosis and cancer-specific survival by race and ethnicity in the United States. JAMA 313:165-173, 201545.

Poortmans P: Postmastectomy radiation in breast cancer with one to three involved lymph nodes: Ending the debate. Lancet 383:2104-2106, 201446.

Margenthaler JA, Ollila DW: Breast conservation therapy versus mastectomy: Shared decision-making strategies and overcoming decisional conflicts in your patients. Ann Surg Oncol 23:3133-3137, 201647.

Performance and practice guidelines for breast-conserving surgery/partial mastectomy. https://docslib.org/doc/8839134/performance-and-practice-guidelines-for-breast-conserving-surgery-partial-mastectomy48.

Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, et al.: Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 347:1233-1241, 200249.

Black DM, Mittendorf EA: Landmark trials affecting the surgical management of invasive breast cancer. Surg Clin North Am 93:501-518, 201350.

Jordan RM, Oxenberg J: Breast cancer conservation therapy, in StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL, StatPearls Publishing, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547708/51.

Citgez B, Yigit B, Bas S: Oncoplastic and reconstructive breast surgery: A comprehensive review. Cureus 14:e21763, 202252.

Carbine NE, Lostumbo L, Wallace J, et al.: Risk-reducing mastectomy for the prevention of primary breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:CD002748, 201853.

Hermann RE, Steiger E: Modified radical mastectomy. Surg Clin North Am 58:743-754, 197854.

Mota BS, Riera R, Ricci MD, et al.: Nipple- and areola-sparing mastectomy for the treatment of breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 11:CD008932, 201655.

NIH Consensus Conference: Treatment of early-stage breast cancer. JAMA 265:391-395, 199156.

Louis-Sylvestre C, Clough K, Asselain B, et al.: Axillary treatment in conservative management of operable breast cancer: Dissection or radiotherapy? Results of a randomized study with 15 years of follow-up. J Clin Oncol 22:97-101, 200457.

Langer I, Guller U, Berclaz G, et al.: Morbidity of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLN) alone versus SLN and completion axillary lymph node dissection after breast cancer surgery: A prospective Swiss multicenter study on 659 patients. Ann Surg 245:452-461, 200758.

Giuliano AE, McCall L, Beitsch P, et al.: Locoregional recurrence after sentinel lymph node dissection with or without axillary dissection in patients with sentinel lymph node metastases: The American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0011 randomized trial. Ann Surg 252:426-433, 201059.

Gentilini OD, Botteri E, Sangalli C, et al.: Sentinel lymph node biopsy vs no axillary surgery in patients with small breast cancer and negative results on ultrasonography of axillary lymph nodes: The SOUND randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 9:1557-1564, 202360.

Clarke M, Collins R, Darby S, et al.: Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15-year survival: An overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 366:2087-2106, 200561.

Darby S, McGale P, Correa C, et al.: Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: Meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials. Lancet 378:1707-1716, 201162.

McGale P, Taylor C, Correa C, et al.: Effect of radiotherapy after mastectomy and axillary surgery on 10-year recurrence and 20-year breast cancer mortality: Meta-analysis of individual patient data for 8135 women in 22 randomised trials. Lancet 383:2127-2135, 201463.

Group (EBCTCG) EBCTC: Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: Patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 378:771-784, 201164.

Peto R, Davies C, Godwin J, et al.: Comparisons between different polychemotherapy regimens for early breast cancer: Meta-analyses of long-term outcome among 100,000 women in 123 randomised trials. Lancet 379:432-444, 201265.

Pagani O, Regan MM, Walley BA, et al.: Adjuvant exemestane with ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancer. N Engl J Med 371:107-118, 201466.

Goss PE, Ingle JN, Pater JL, et al.: Late extended adjuvant treatment with letrozole improves outcome in women with early-stage breast cancer who complete 5 years of tamoxifen. J Clin Oncol 26:1948-1955, 200867.

Cuzick J, Sestak I, Baum M, et al.: Effect of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: 10-year analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol 11:1135-1141, 201068.

Harbeck N, Gnant M: Breast cancer. Lancet 389:1134-1150, 201769.

Blok EJ, Derks MGM, van der Hoeven JJM, et al.: Extended adjuvant endocrine therapy in hormone-receptor positive early breast cancer: Current and future evidence. Cancer Treat Rev 41:271-276, 201570.

McDonald ES, Clark AS, Tchou J, et al.: Clinical diagnosis and management of breast cancer. J Nucl Med 57:9S-16S, 201671.

Waks AG, Winer EP: Breast cancer treatment: A review. JAMA 321:288-300, 201972.

Cortazar P, Zhang L, Untch M, et al.: Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: The CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet 384:164-172, 201473.

Perez EA, Romond EH, Suman VJ, et al.: Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive breast cancer: Planned joint analysis of overall survival from NSABP B-31 and NCCTG N9831. J Clin Oncol 32:3744-3752, 201474.

Goldhirsch A, Gelber RD, Piccart-Gebhart MJ, et al.: 2 years versus 1 year of adjuvant trastuzumab for HER2-positive breast cancer (HERA): An open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 382:1021-1028, 201375.

Harbeck N, Penault-Llorca F, Cortes J, et al.: Breast cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers 5:66, 201976.

Schmid P, Adams S, Rugo HS, et al.: Atezolizumab and nab-paclitaxel in advanced triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med 379:2108-2121, 201877.

Cortes J, Rugo HS, Cescon DW, et al.: Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in advanced triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med 387:217-226, 202278.

Nagrani RT, Budukh A, Koyande S, et al.: Rural urban differences in breast cancer in India. Indian J Cancer 51:277-281, 201479.

Chaturvedi M, Sathishkumar K, Lakshminarayana SK, et al.: Women cancers in India: Incidence, trends and their clinical extent from the National Cancer Registry programme. Cancer Epidemiol 80:102248, 202280.

Negi J, Nambiar D: Intersectional social-economic inequalities in breast cancer screening in India: Analysis of the National Family Health Survey. BMC Womens Health 21:324, 202181.

Mathew A, George PS, Ramadas K, et al.: Sociodemographic factors and stage of cancer at diagnosis: A population-based study in South India. J Glob Oncol 5:1-10, 201982.

Mathur P, Sathishkumar K, Chaturvedi M, et al.: Cancer Statistics, 2020: Report from National Cancer Registry Programme, India. JCO Glob Oncol 6:1063-1075, 202083.

Indian Council of Medical Research: Cancer Samiksha. https://ncdirindia.org/cancersamiksha/84.

Chatterjee S, Chattopadhyay A, Senapati SN, et al.: Cancer registration in India—Current scenario and future perspectives. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 17:3687-3696, 201685.

Elrod JK, Fortenberry JL: The hub-and-spoke organization design: An avenue for serving patients well. BMC Health Serv Res 17:457, 2017