INTRODUCTION

Multiple myeloma (MM), the second most common hematologic malignancy, poses a global health risk, with 160,000 cases and 106,000 mortalities worldwide. Over the years, multiple therapeutic modalities have been approved for MM treatment, including melphalan (1964), autologous stem-cell transplantation (SCT; 1996), thalidomide (1999), bortezomib (2003), lenalidomide (2005), carfilzomib (2012), pomalidomide (2013), daratumumab (2015), elotuzumab (2015), ixazomib (2015), and selinexor (2020), all of which demonstrate substantial survival rate improvements.

CONTEXT

Key Objective

What is the accessibility of myeloma therapies, particularly cellular therapies, in countries outside the United States?

Knowledge Generated

A study of 95 respondents from 33 countries found that most had good access to noncellular therapies for multiple myeloma, but drugs like isatuximab and ixazomib faced accessibility challenges. Only 17% had access to chimeric antigen receptor-T-cell therapy, and 23% had access to approved T-cell engagers, with the financial strain being the main barrier for patients and health care systems.

Relevance

Key barriers to accessing myeloma therapies include financial strain on patients and health care systems and insufficient regulatory approvals. This survey seeks to partner with health care organizations, governments, and industry to develop strategies for improving access to new therapies.

Since 2021, cellular therapies have emerged in the field, with the introduction of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T)-cell therapy, idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel), and ciltacabtagene autoleucel (cilta-cel), which was approved the following year. In August 2022, the first T-cell engager (TCE), teclistamab, was approved for MM treatments. Access to novel treatments is essential for improving survival rates in patients with MM. Innovative therapies, including immunotherapies and CAR-T-cell therapies, offer significant benefits, such as complete remission and extended progression-free survival (PFS)., However, high costs and health care access disparities hinder treatment, especially for marginalized groups. Studies show better outcomes for patients treated at high-volume facilities and by specialized oncologists, particularly at NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers, which are linked to lower mortality risks.

Despite these advancements, global health care disparities in access to proper MM care remain a significant challenge. Access to MM therapies varies worldwide and can differ significantly within the same continent. For instance, certain European countries, such as Bosnia and Macedonia, struggle with limited access to generic medicines, whereas countries like Germany demonstrate a more accessible environment, including access to CAR-T. Access can be limited for various reasons such as manufacturing or importation, affordability, local agency approval, and government budgeting.

Furthermore, it is anticipated that there will be differences in access to equity based on countries' policies and economic levels. Therefore, we aimed to investigate whether economic factors are associated with better access using a country's health expenditure (HE). Developed nations such as the United States and the United Kingdom allocate approximately 11.3% and 18.3% of their gross domestic product (GDP) to health care. By contrast, low-income countries, such as the Philippines, spend only 6% of their GDP on health care.

Variations in treatment and drug accessibility lead to subsequent differences in overall survival and quality of life. Over the past few decades, numerous studies have addressed the sociodemographic disparities in the accessibility of MM care. In this survey, we aimed to assess the accessibility of various MM therapy modalities and their barriers, as perceived by oncologists worldwide. To our knowledge, this is the first-ever study from the perspective of oncologists worldwide that questions the fair access to MM drugs, which were not published in any peer-reviewed journals.

METHODS

Investigators at the US Myeloma Innovative Collaborative (USMIRC) conducted an online survey on global access to various MM therapy modalities and their barriers to access.

Survey Design and Distribution

The first draft of the survey was prepared by N.A. and R.A. and finalized with input from N.A., A.-O.A., AS, and SS as biostatisticians. USMIRC members conducted online practice runs of the finalized Google Forms survey to assess flow, estimate completion time, and identify troubleshoot errors. Run responses were deleted before the formal release of the survey and were designed to be completed in one session without the option to complete it later. The sections of the survey included respondents' demographics, availability/access to drugs, and barriers to access. The survey included questions that specifically addressed access and barriers to access. The following 15 noncellular therapy drugs and modalities were addressed: lenalidomide, pomalidomide, bortezomib, carfilzomib, ixazomib, cyclophosphamide, melphalan, bendamustine, daratumumab, isatuximab, selinexor, elotuzumab, allogeneic/autologous SCT, and three cellular therapies, including two CAR-T therapies: ide-cel and cilta-cel, and one TCE, teclistamab. The respondents categorized each medication as “easily accessible,” “moderately accessible,” “not readily accessible” or “no access” (Appendix Table A1). A USMIRC Global Access to Multiple Myeloma Therapies (GLAMM) subcommittee (A.-O.A., N.A., F.S.A., S.K.H.) was formed to identify global participants and was responsible for inviting them. The committee invited participants based on their global connections and confirmed their practice websites. Those with plasma cell–focused academic practices and general hematologists/oncologists (H/Os) were invited.

The survey was sent electronically to 176 H/Os worldwide (excluding the United States) and was performed between June 18, 2023, with reminders every 2 weeks. The inclusion criteria for the selection of physicians were determined globally. This included practicing H/Os to treat MM, identified after a web search of hospitals in the countries of interest. Only those with verified institutional e-mail addresses were included in this study. The final responses, as of July 17, 2023, were included in the analysis. Descriptive statistics were used, and the proportions were reported. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Kansas University Medical Center.

Categories and Statistical Methods

To categorize a region as having adequate access, the cutoff to access was 60% of responders affirming “easily accessible” or “moderately easy access.” The cutoff of 60% was predetermined as a consensus from the GLAMM subcommittee, and HE of a country's GDP from the World Bank was used to categorize countries into two groups: high health care investing nations (HHINs), which included countries spending >10% of their GDP on health care, and low health care investing nations (LHINs), which included countries spending <10% on health care.

Descriptive statistics were used for analyses. We did not perform statistical analysis in this study. Only those participants who completed 100% of the survey were included in the final analysis.

RESULTS

Ninety-five (54%) of the 176 surveyed H/Os from 33 countries completed all the surveys (100%). Fifty-one percent worked in university-based academic centers, and 17% had a dedicated focus on plasma cell disorders. Figure 1 shows an overview of the countries and continents used in our survey. Refer to Appendix Table A1 for questions 1-7, which address the demographics of our respondents.

FIG 1

Number of countries per continent represented in the survey.

Access to Therapies

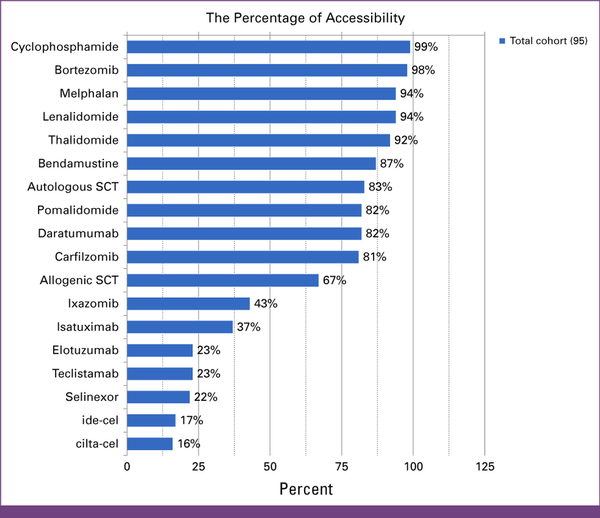

Figure 2 provides an overview of the drugs and therapeutic modalities accessed for MM treatment, from most to least. Question 8 in Appendix Table A1 addressed the availability of drugs or therapeutic modalities in the cohort.

FIG 2

Global access to MM therapies among the survey cohort. The access cutoff is set at 60%, where respondents reported access as moderately easy or easy. cilta-cel, ciltacabtagene autoleucel; ide-cel, idecabtagene vicleucel; MM, multiple myeloma; SCT, stem-cell transplant.

Noncellular Therapies

Most respondents from the global cohort (n = 95) had adequate access to most noncellular therapies, as shown in Figure 2. Notably, ixazomib (43%), isatuximab (37%), selinexor (22%), and elotuzumab (23%) were not assessed by respondents.

Cellular Therapies

Only 17% of the participants in the survey reported adequate access to ide-cel and 16% reported adequate access to cilta-cel, whereas 23% reported adequate access to TCE (23%).

Access per Continent

Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of the accessibility of specific therapies across continents.

TABLE 1

Survey Results Evaluating the Myeloma Therapy Agent's Accessibility Across Continents

| Global Cohort (n = 95) | Therapy | Countries by Continent Total Respondents: 95 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe (n = 18), % | Asia (n = 53), % | Africa (n = 7), % | North America (n = 3), % | South America (n = 11), % | Oceania (n = 3), % | ||

| Adequate access (defined as >60% of respondents from the region reporting easy/moderately easy access) | Cyclophosphamide | 100 | 98 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Bortezomib | 100 | 98 | 86 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Melphalan | 95 | 92 | 100 | 100 | 91 | 100 | |

| Lenalidomide | 100 | 94 | 86 | 67 | 91 | 100 | |

| Thalidomide | 89 | 92 | 100 | 33 | 100 | 100 | |

| Autologous SCT | 89 | 79 | 86 | 67 | 91 | 100 | |

| Allogeneic SCT | 83 | 60 | 71 | 33 | 73 | 100 | |

| Carfilzomib | 89 | 83 | 43 | 67 | 82 | 100 | |

| Pomalidomide | 95 | 89 | 43 | 67 | 55 | 100 | |

| Bendamustine | 89 | 94 | 86 | 33 | 82 | 33 | |

| Daratumumab | 95 | 89 | 29 | 33 | 73 | 100 | |

| Limited access (defined as <60% of respondents from the region reporting not readily accessible or inaccessible) | Ixazomib | 78 | 34 | 29 | 33 | 55 | 0 |

| Selinexor | 22 | 21 | 29 | 33 | 0 | 100 | |

| Isatuximab | 83 | 26 | 29 | 33 | 27 | 0 | |

| Elotuzumab | 44 | 17 | 29 | 0 | 9 | 67 | |

| cilta-cel | 22 | 15 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| ide-cel | 22 | 15 | 29 | 0 | 9 | 0 | |

| Teclistamab | 50 | 17 | 29 | 0 | 9 | 0 | |

Noncellular Therapies

Among the 15 noncellular therapies surveyed, European physicians had access to all modalities, except for selinexor (22%) and elotuzumab (44%). Physicians in Oceania have limited access to bendamustine (33%), ixazomib (0%), and isatuximab (0%). Physicians in Asia have reported limited access to ixazomib (34%), selinexor (21%), isatuximab (26%), and elotuzumab (17%). South America reported limited access to pomalidomide (55%) and ixazomib (55%), followed by selinexor (0%), isatuximab (27%), and elotuzumab (9%). North America (excluding the United States) and Africa faced limited access to MM therapies, as shown in Table 1.

Cellular Therapies

When categorized by continent, none of the continents had adequate access to TCE or CAR-T although Europe had the most access to cellular therapy, particularly TCE (50%).

Access per HE

Responses were gathered from 19 respondents in the HHIN group and 76 in the LHIN group.

Among HHINs (n = 19), the following agents were adequately accessible: thalidomide, lenalidomide, bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, melphalan, carfilzomib and pomalidomide, daratumumab, isatuximab, ixazomib, bendamustine, allogeneic stem-cell transplant, and autologous stem-cell transplant. Only elotuzumab and selinexor had limited access (<60%) to this category. Among patients in LHINs (n = 76), limited access was observed with isatuximab (26%), ixazomib (38%), elotuzumab (17%), and selinexor (17%).

The HHIN and LHIN groups had limited access to cellular therapy. In the HHIN group (n = 19), 26% reported access to CAR-T and 42% reported access to TCE.

In the LHIN group, encompassing 76 respondents, TCE and CAR-T had limited access, with rates between 13% and 17%.

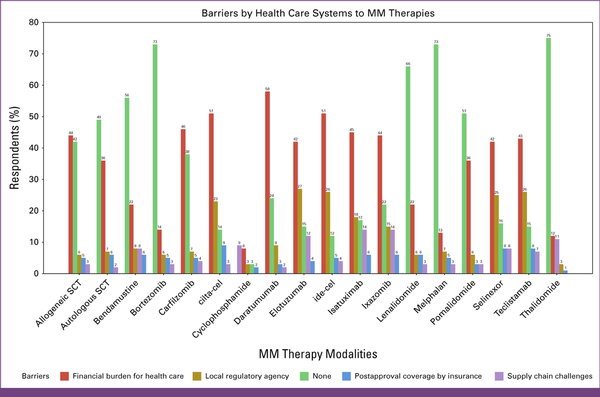

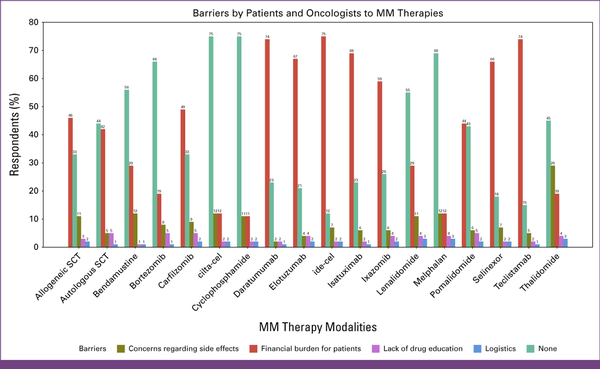

In Appendix Table A1, questions 9 and 10 assessed the barriers to accessing MM drugs or therapy modalities, which are defined in Figures 3 and 4. Figure 3 outlines barriers within the health care system, including financial and infrastructure barriers, and Figure 4 outlines the barriers faced by patients and oncologists.

FIG 3

Barriers by the health care system in terms of finance and infrastructure. cilta-cel, ciltacabtagene autoleucel; ide-cel, idecabtagene vicleucel; MM, multiple myeloma; SCT, stem-cell transplant.

FIG 4

Barriers identified by patients and oncologists. cilta-cel, ciltacabtagene autoleucel; ide-cel, idecabtagene vicleucel; MM, multiple myeloma; SCT, stem-cell transplant.

The financial burden for health care was the top barrier for the following drugs: carfilzomib (46%), ixazomib (44%), daratumumab (58%), isatuximab (45%), selinexor (42%), and elotuzumab (42%). Another significant barrier was the lack of local agency approval for ixazomib (15%), isatuximab (18%), selinexor (25%), and elotuzumab (27%). Regarding SCT, 33% of respondents reported the absence of barriers to allogeneic SCT, whereas 44% reported a lack of barriers to autologous SCT.

The financial burden for patients was the top-cited barrier for isatuximab (69%), elotuzumab (67%), selinexor (66%), ixazomib (59%), daratumumab (58%), and carfilzomib (49%).

Most respondents (>50%) reported the absence of barriers to lenalidomide, bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, melphalan, and bendamustine.

For cellular therapies, 51% of the respondents identified financial challenges in health care as a primary obstacle to CAR-T therapy accessibility, and 42% expressed similar concerns for TCE. The lack of local agency approval emerged as a significant barrier for both TCE and CAR-T (26% and 24%, respectively). In addition, 14% and 15% of the respondents cited supply chain difficulties as a major problem for both CAR-T and TCE, respectively.

A total of 75% of H/Os reported financial burden for patients as a top barrier for CAR-T and TCE, and only approximately 14% reported the absence of barriers to accessing these drugs.

DISCUSSION

The first global assessment of access to and barriers to MM treatment was conducted in a cross-sectional study in 2023. The survey had fair representation from all continents, and there was a relatively high percentage of completed responses (54%) compared with the average response rate for online surveys (44%).

The financial burden for patients and health care service providers (because of the high costs of prolonged treatment) arose as a significant limiting factor in the worldwide accessibility to many MM therapies. Before initiating the survey, we expected access to be a major problem worldwide and that the financial burden is, in fact, one of the biggest burdens given its high costs in the United States; we expected that it might not even be available worldwide. However, no survey has been conducted in this era to study myeloma therapy access worldwide. Limited access to innovative drugs for MM significantly affects patient outcomes, as demonstrated by several studies from different regions. In the absence of CAR-T or TCE therapies, patients typically rely on conventional treatments, including proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulatory drugs, and monoclonal antibodies. From our survey, we noticed that most continents had access to most noncellular therapies. However, studies have shown that cellular therapies, such as CAR-T therapy, particularly those targeting B-cell maturation antigen, significantly improve PFS and overall response rates in patients with relapse/refractory MM. For instance, Brudno et al reported that CAR-T therapy led to a median PFS of 13.3 months compared with 4.4 months with standard treatments. Similarly, García-Guerrero et al highlighted that traditional therapies, including novel agents such as daratumumab and carfilzomib, often fail to completely eradicate myeloma cells, leading to relapse and poorer outcomes. A 2022 survey reported in Cancer Discovery found that only approximately 25% of patients with MM who were waiting for CAR-T-cell therapy received treatment because of manufacturing bottlenecks and limited supply. Even in high-income countries, such as the United States, access to CAR-T therapy faces significant obstacles because of financial toxicity, logistical challenges, and manufacturing bottlenecks. A survey conducted among US oncologists highlighted these issues as major barriers to CAR-T therapy, resulting in inequitable outcomes stemming from structural disparities in access to quality health care. This limited access leads to suboptimal treatment outcomes compared with those who receive CAR-T therapy., This again highlights the importance of shedding light on the worldwide access to novel MM treatments.

Drugs approved earlier are likely to be available as generic drugs or have more affordable biosimilars, which can be seen in the results of our survey, where most drugs approved before 2015 were more easily accessible.,, Specific therapies approved after 2015, which are not generic (such as selinexor, elotuzumab, isatuximab, and ixazomib) and priced at over $100,000 US dollars (USD) per year, have posed notable challenges in global accessibility, and this is very evident in our survey where most continents had no access to those medications. Daratumumab and carfilzomib, categorized as accessible by most H/Os around the world, were also noted as unattainable by some because of the limited financial capabilities of patients or health care. In an analysis conducted on patients with MM in a US community–based practice setting, analysts found that daratumumab is used at a more frequent dosing schedule with a 14% higher usage than the FDA-approved label recommendation the United States, ultimately increasing the 1-year treatment cost by $31,000 USD.

In addition, the use of newer therapies and multiple drug combinations in the up-front and relapsed settings contributes to the increased costs associated with antimyeloma treatment. Changes in the treatment approach for myeloma have shifted toward using combinations of more drugs, moving from doublet to triplet regimens, and now quadruplet regimens are seen in recent studies such as GRIFFIN and PURSEUS.

The disparities in the availability of cellular therapies are more pronounced, given an estimated cost of over $400,000 USD for CAR-T per patient, covering inpatient and outpatient management. Similarly, TCE is not exempt from high expenses, averaging around $300,000 over 10 months. The results of this study reveal that these numbers emphasize a significant global barrier to adopting CAR-T and TCE. Patients with MM are likely to experience financial hardships owing to high costs, increased out-of-pocket burden, and prolonged treatment duration. Moreover, in April 2024, based on CARTITIDE-4 and KarMMa-3, cilta-cel and ide-cel were approved in earlier lines in the United States, making the need to address barriers even more urgent.

The high cost of MM drugs is a financial burden, even in countries with universal health coverage, and can strain their resources. Regulatory barriers, often rooted in financial constraints, contribute to this disparity. For example, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) funds MM therapy in Australia. However, CAR-T and TCE are not currently PBS-funded; patients can only receive these therapies in clinical trials. The Therapeutic Goods Administration in Australia approved only cilta-cel in 2023 for MM treatment, following three lines of previous therapies. However, without the approval of the Medical Services Advisory Committee, cilta-cel will not receive public funding in Australia, leading to substantial patient expenses exceeding $500,000 USD and further reducing patient access to affordable treatment options.

Conducting MM therapies as part of clinical trials is a strategy to help overcome the cost challenges of approved therapies, making it feasible in low- and middle-income countries. The rapid enrollment of trials worldwide has expedited the regulatory approval of innovative therapies. A systematic review revealed that clinical trials for MM leading to FDA approval were predominantly conducted in high-income European and Central Asian countries. By contrast, low-income South Asian countries showed no patient enrollment in these trials; consequently, no approvals were granted.

Cost-effective manufacturing methods and the development of indigenous CAR-T therapies are being explored to make treatment more accessible in low-/middle-income areas. In 2023, India achieved its first approval of indigenous CAR-T therapy, following the outcomes of two clinical trials conducted within the country. The cost-effectiveness of CAR-T therapy (priced around $50,000 USD) could enhance accessibility in India, as opposed to the $400,000 USD expense per infusion in the United States.

According to our surveyed H/Os, the prolonged agency approval process serves as an additional barrier to accessing new MM drugs. Typically, new anticancer drugs are initially approved in the United States, followed by marketing authorizations in other countries around 12-17 months later. An example is the initial marketing approval granted to elotuzumab and isatuximab in November 2015., The United States has achieved instant marketing approval, whereas in Europe, the average time was 6 months for elotuzumab and 12 months for ixazomib.,

Specific to European countries, receiving approval from the European Medicines Agency does not automatically ensure reimbursement. Reimbursement constraints for drugs in Europe require Phase III randomized controlled trial data. In addition, the high prices of drugs often lead to prolonged negotiation periods. For example, a country's ministry may choose to temporarily suspend expensive medications based on certain criteria for national reimbursement, aiming to negotiate a mutually acceptable price with the pharmaceutical company.

Surprisingly, the survey results showed that HHINs face challenges similar to those of LHINs. Several countries within the HHINs face barriers to access certain therapies despite the advantages of a public health care system. An LHIN such as India allocates a significantly lower proportion of its GDP (2.1%) to health care than countries with Universal Health Coverage models, where the average health care spending reaches 10% of their GDP. Consequently, health care systems require considerable out-of-pocket expenditure for the management of cancer patients. Similarly, the increasing cancer burden in Africa, coupled with the high cost of care, causes government agencies to hesitate to cover cancer treatment through national health insurance plans. The lack of health coverage, particularly for cancer care, in many African countries exacerbates access disparities.

Postapproval coverage, supply chain limitations, and logistics, such as travel costs for therapy, can also be reasons for limited access; however, these factors were not cited as a top barrier to readily accessible MM therapies. This is likely because of high costs and the drugs that are not yet approved, the significance of postapproval coverage or logistics diminishes, and other barriers, particularly financial considerations and local agency approval, take precedence.

The study has certain limitations, including inadequate representation from all continents, including Asian countries such as China and Russia and certain African countries. In addition, since this was a general global survey, we needed to understand and analyze all systems in individual countries. Selection bias was one of the limitations as we only chose physicians with whom the USMIRC committee has a connection. This approach ensures the quality and relevance of the data collected. To enhance survey response rates from oncologists worldwide in the future, we recommend the following strategies: Partnering with oncology associations, offering ethical incentives, using a variety of communication channels, ensuring that surveys are mobile-friendly, avoiding distribution during busy periods or major conferences, and using gentle reminders for follow-up requests. The survey lacks validation because it does not specify the line of treatment for which the drug is available. This is crucial because there is significant variability in drug access depending on the line of treatment.

Moreover, the survey lacked participation from health care system administrators and regulatory agencies in various countries. The experience levels of the H/Os surveyed were vastly diverse, with many not specializing in plasma cell disorders. Thus, the survey did not account for participant variability.

Another bias of this study is that, by design, it depended on estimates of the size of problems by the surveyed H/Os rather than the actual number of treatments.

In conclusion, this survey highlights that access to innovative treatments for MM remains a global issue. The primary barriers to accessing myeloma therapies include the financial burden faced by patients and health care systems coupled with the lack of approval from regulatory agencies. This survey established partnerships with health care organizations, international agencies, governments, regulatory bodies, policymakers, and industry partners to develop effective strategies for improving access to emerging therapies.

DISCLAIMER

The authors assume full responsibility for the content of this publication. The views and interpretations articulated herein solely represent the authors' viewpoints and should not be interpreted as official endorsements by governmental entities.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Rawan Atallah, Yara Shatnawi, MD Fathima Shehnaz Ayoobkhan, Muhammad Umair Mushtaq, Shebli Atrash, Zahra Mahmoudjafari, Faiz Anwer, Nausheen Ahmed, Al-Ola Abdallah

Financial support: Joseph P. McGuirk

Administrative support: Shabeeha Rana, Joseph P. McGuirk, Nausheen Ahmed, Al-Ola Abdallah

Provision of study materials or patients: Shabeeha Rana, Rakesh Popat, Joseph P. McGuirk, Zahra Mahmoudjafari, Faiz Anwer

Collection and assembly of data: Rawan Atallah, Yara Shatnawi, MD Fathima Shehnaz Ayoobkhan, Md Saiful Islam Saif, Shabeeha Rana, Aytaj Mammadzadeh, Nihar Desai, Thiago Xavier Carneiro, Joseph P. McGuirk, Shebli Atrash, Zahra Mahmoudjafari, Nada Hammad, Faiz Anwer, Nausheen Ahmed, Al-Ola Abdallah

Data analysis and interpretation: Rawan Atallah, Yara Shatnawi, Md Saiful Islam Saif, Menahil Naeem, Emerson Logan, Muhammad Umair Mushtaq, Shahrukh K. Hashmi, Benlazar Mohamed, Rakesh Popat, Joseph P. McGuirk, Nada Hammad, Faiz Anwer, Nausheen Ahmed, Al-Ola Abdallah

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/go/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Yara Shatnawi

Employment: cleveland clinic

Muhammad Umair Mushtaq

Research Funding: Iovance Biotherapeutics (Inst)

Shahrukh K. Hashmi

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Sanofi

Thiago Xavier Carneiro

Honoraria: Johnson & Johnson/Janssen, Pfizer, AbbVie

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Janssen

Rakesh Popat

Honoraria: Johnson & Johnson/Janssen, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie, Celgene, BMS

Consulting or Advisory Role: GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, Janssen, Galapagos NV, Sanofi, Regeneron

Speakers' Bureau: Pfizer

Research Funding: GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Pfizer (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Janssen, GlaxoSmithKline

Joseph P. McGuirk

Employment: University of Kansas Health System

Leadership: University of Kansas Cancer Center

Honoraria: Kite, a Gilead company, AlloVir, Nektar, Sana Biotechnology, Bristol Myers Squibb/Sanofi, Novartis, crispr therapeutics, CARGO Therapeutics, Autolus, Legend Biotech

Consulting or Advisory Role: Kite, a Gilead company, Juno Therapeutics, Allovir, Magenta Therapeutics, EcoR1 Capital, crispr therapeutics, Fosun Kite Biotechnology Co, Ltd, Sanofi US Services, Inc, Novartis, Nektar, Sana Biotechnology, Inc

Speakers' Bureau: Kite/Gilead

Research Funding: Novartis (Inst), Fresenius Biotech (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst), Bellicum Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Gamida Cell (Inst), Pluristem Therapeutics (Inst), Kite, a Gilead company (Inst), AlloVir (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Kite, a Gilead company, Syncopation Life Sciences, SITC/ACCC

Shebli Atrash

Leadership: ACCRU

Honoraria: Janssen, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, Sanofi

Research Funding: GlaxoSmithKline, Amgen, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Janssen Oncology (Inst), Celgene/Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst)

Zahra Mahmoudjafari

Leadership: Hematology Oncology Pharmacists Association

Honoraria: Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation, Kite/Gilead, Genentech, Pfizer, Sanofi

Nada Hammad

Honoraria: Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi/Aventis, Therakos

Speakers' Bureau: Novartis

Faiz Anwer

Consulting or Advisory Role: BMS, Poseida Therapeutics, GI Innovation, Caribou Biosciences

Speakers' Bureau: Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation

Research Funding: Celgene (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Caribou Biosciences (Inst), Caribou Biosciences

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol Myers Squibb

Open Payments Link:https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/16726

Nausheen Ahmed

Consulting or Advisory Role: Kite/Gilead, BMS, Legend Biotech, Invivyd

Research Funding: Kite/Gilead (Inst)

Al-Ola Abdallah

Research Funding: Celgene (Inst), Seagen (Inst), AbbVie (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb/Medarex (Inst), Sanofi (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: PSA vaccine patent

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

Yara Shatnawi

Employment: cleveland clinic

Muhammad Umair Mushtaq

Research Funding: Iovance Biotherapeutics (Inst)

Shahrukh K. Hashmi

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Sanofi

Thiago Xavier Carneiro

Honoraria: Johnson & Johnson/Janssen, Pfizer, AbbVie

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Janssen

Rakesh Popat

Honoraria: Johnson & Johnson/Janssen, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie, Celgene, BMS

Consulting or Advisory Role: GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, Janssen, Galapagos NV, Sanofi, Regeneron

Speakers' Bureau: Pfizer

Research Funding: GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Pfizer (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Janssen, GlaxoSmithKline

Joseph P. McGuirk

Employment: University of Kansas Health System

Leadership: University of Kansas Cancer Center

Honoraria: Kite, a Gilead company, AlloVir, Nektar, Sana Biotechnology, Bristol Myers Squibb/Sanofi, Novartis, crispr therapeutics, CARGO Therapeutics, Autolus, Legend Biotech

Consulting or Advisory Role: Kite, a Gilead company, Juno Therapeutics, Allovir, Magenta Therapeutics, EcoR1 Capital, crispr therapeutics, Fosun Kite Biotechnology Co, Ltd, Sanofi US Services, Inc, Novartis, Nektar, Sana Biotechnology, Inc

Speakers' Bureau: Kite/Gilead

Research Funding: Novartis (Inst), Fresenius Biotech (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst), Bellicum Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Gamida Cell (Inst), Pluristem Therapeutics (Inst), Kite, a Gilead company (Inst), AlloVir (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Kite, a Gilead company, Syncopation Life Sciences, SITC/ACCC

Shebli Atrash

Leadership: ACCRU

Honoraria: Janssen, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, Sanofi

Research Funding: GlaxoSmithKline, Amgen, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Janssen Oncology (Inst), Celgene/Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst)

Zahra Mahmoudjafari

Leadership: Hematology Oncology Pharmacists Association

Honoraria: Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation, Kite/Gilead, Genentech, Pfizer, Sanofi

Nada Hammad

Honoraria: Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi/Aventis, Therakos

Speakers' Bureau: Novartis

Faiz Anwer

Consulting or Advisory Role: BMS, Poseida Therapeutics, GI Innovation, Caribou Biosciences

Speakers' Bureau: Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation

Research Funding: Celgene (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Caribou Biosciences (Inst), Caribou Biosciences

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol Myers Squibb

Open Payments Link:https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/16726

Nausheen Ahmed

Consulting or Advisory Role: Kite/Gilead, BMS, Legend Biotech, Invivyd

Research Funding: Kite/Gilead (Inst)

Al-Ola Abdallah

Research Funding: Celgene (Inst), Seagen (Inst), AbbVie (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb/Medarex (Inst), Sanofi (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: PSA vaccine patent

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

APPENDIX

TABLE A1

Demographics, Access, and Barriers

| Survey Questions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Demographics | Percentage of Respondents |

| Total | Global cohort (95%) | 100 |

| Q1 How would you describe your practice? | General hematology-oncology | 48 |

| Plasma cell disorders focused | 17 | |

| Both | 35 | |

| Q2 What is your gender identity? | Male | 75 |

| Female | 25 | |

| Q3 What best describes your race/ethnicity? | White | 26 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 25 | |

| Asian | 33 | |

| South Asian | 13 | |

| Others | 3 | |

| Q4 How would you describe your practice? | University-based academic centers | 50.5 |

| Community academic medical centers | 11.5 | |

| Private/community practice | 18 | |

| Hybrid | 17 | |

| Others | 3 | |

| Q5 What's most common health insurance plans of your patients based on frequency | Publicly funded insurance | 61 |

| Self-pay | 21 | |

| Private/commercial insurance | 18 | |

| Q6 On which continent is your practice located? | Europe | 19 |

| Asia | 56 | |

| Africa | 7 | |

| North America | 3 | |

| South America | 12 | |

| Australia | 33 | |

| Q7: How many years of experience do you have treating Multiple Myeloma patients? | <1 year | 6 |

| 2-5 years | 28 | |

| 6-10 years | 23 | |

| 11-20 years | 31 | |

| >20 years | 12 | |

| Availability of Drugs or Therapy Modalities | Q8: How Would You Rate the Availability of Each Drug or Modality of Therapy in Your Country? Please Select One Option for Each | |

|---|---|---|

| Adequate Access (available/moderately available), % | Limited Access (not readily available, unavailable), % | |

| Cyclophosphamide | 99 | 1 |

| Bortezomib | 98 | 2 |

| Melphalan | 94 | 6 |

| Lenalidomide | 94 | 6 |

| Thalidomide | 92 | 8 |

| Autologous stem-cell transplant | 83 | 17 |

| Allogeneic stem-cell transplant | 67 | 33 |

| Carfilzomib | 81 | 19 |

| Pomalidomide | 82 | 18 |

| Bendamustine | 87 | 13 |

| Daratumumab | 82 | 18 |

| Ixazomib | 43 | 57 |

| Selinexor | 22 | 78 |

| Isatuximab | 37 | 63 |

| Elotuzumab | 23 | 77 |

| cilta-cel | 16 | 84 |

| ide-cel | 17 | 83 |

| Teclistamab | 23 | 77 |

| Barrier of Drugs and Therapy Modalities | Q9: What Are the Main Barriers, in Terms of Financial and Infrastructure Constraints, That Hinder Access to These Drugs and Treatments? Select All That Apply | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Burden for Healthcare (eg, costs to stock drugs, building infrastructure), % | Supply Chain Challenges (eg, limited supply, stock, and manufacture), % | Local Regulatory Agency Approval, % | Postapproval Coverage by Insurance Companies, % | None, % | |

| Cyclophosphamide | 9 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 83 |

| Bortezomib | 14 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 73 |

| Melphalan | 7 | 13 | 5 | 3 | 73 |

| Lenalidomide | 22 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 66 |

| Thalidomide | 11 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 75 |

| Allogeneic stem-cell transplant | 44 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 42 |

| Autologous stem-cell transplant | 36 | 6 | 2 | 7 | 49 |

| Carfilzomib | 46 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 38 |

| Pomalidomide | 36 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 51 |

| Bendamustine | 22 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 56 |

| Daratumumab | 58 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 24 |

| Ixazomib | 44 | 14 | 15 | 6 | 22 |

| Selinexor | 42 | 17 | 25 | 8 | 8 |

| Isatuximab | 45 | 15 | 18 | 6 | 17 |

| Elotuzumab | 42 | 16 | 27 | 4 | 12 |

| cilta-cel | 51 | 15 | 23 | 8 | 3 |

| ide-cel | 51 | 13 | 26 | 7 | 3 |

| Teclistamab | 43 | 15 | 26 | 8 | 7 |

| Q10: What Factors Influence the Choices Made by Patients and Oncologists Regarding Drug Usage? Select All That Apply | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Burden for Patients, % | Concerns Regarding Side Effects, % | Logistics (travel costs to the treatment center or hospital), % | Lack of Drug Education, % | None, % | |

| Cyclophosphamide | 11 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 75 |

| Bortezomib | 19 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 66 |

| Melphalan | 12 | 12 | 3 | 4 | 69 |

| Lenalidomide | 29 | 11 | 4 | 2 | 55 |

| Thalidomide | 19 | 29 | 3 | 4 | 45 |

| Allogeneic stem-cell transplant | 46 | 11 | 4 | 1 | 33 |

| Autologous stem-cell transplant | 42 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 44 |

| Carfilzomib | 49 | 9 | 6 | 2 | 33 |

| Pomalidomide | 44 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 43 |

| Bendamustine | 29 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 56 |

| Daratumumab | 74 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 23 |

| Ixazomib | 59 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 26 |

| Selinexor | 66 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 18 |

| Isatuximab | 69 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 23 |

| Elotuzumab | 67 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 21 |

| cilta-cel | 75 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 12 |

| ide-cel | 75 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 12 |

| Teclistamab | 74 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 15 |

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We acknowledge all our colleagues and the respondents who completed the survey.

REFERENCES

1.

Ludwig H, Novis Durie S, Meckl A, et al.: Multiple myeloma incidence and mortality around the globe; interrelations between health access and quality, economic resources, and patient empowerment. Oncologist 25:e1406-e1413, 20202.

Kegyes D, Constantinescu C, Vrancken L, et al.: Patient selection for CAR T or BiTE therapy in multiple myeloma: Which treatment for each patient? J Hematol Oncol 15:78, 20223.

Anderson KC: Progress and paradigms in multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res 22:5419-5427, 20164.

Raedler L: Velcade (bortezomib) receives 2 new FDA indications: For retreatment of patients with multiple myeloma and for first-line treatment of patients with mantle-cell lymphoma. Am Health Drug Benefits 8:135-140, 20155.

Richter J, Madduri D, Richard S, et al.: Selinexor in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Ther Adv Hematol 11:204062072093062, 20206.

Shirley M: Ixazomib: First global approval. Drugs 76:405-411, 20167.

Gormley NJ, Ko CW, Deisseroth A, et al.: FDA drug approval: Elotuzumab in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone for the treatment of relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res 23:6759-6763, 20178.

Bhatnagar V, Gormley NJ, Luo L, et al.: FDA approval summary: Daratumumab for treatment of multiple myeloma after one prior therapy. Oncologist 22:1347-1353, 20179.

Fotiou D, Gavriatopoulou M, Terpos E, et al.: Pomalidomide- and dexamethasone-based regimens in the treatment of refractory/relapsed multiple myeloma. Ther Adv Hematol 13:204062072210900, 202210.

Herndon TM, Deisseroth A, Kaminskas E, et al.: U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval: Carfilzomib for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res 19:4559-4563, 201311.

Kane RC, Bross PF, Farrell AT, et al.: Velcade®: U.S. FDA approval for the treatment of multiple myeloma progressing on prior therapy. Oncologist 8:508-513, 200312.

Zhou S, Wang F, Hsieh TC, et al.: Thalidomide–A notorious sedative to a wonder anticancer drug. Curr Med Chem 20:4102-4108, 201313.

Ahmed N, Shahzad M, Shippey E, et al.: Socioeconomic and racial disparity in chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy access. Transplant Cell Ther 28:358-364, 202214.

Kang C: Teclistamab: First approval. Drugs 82:1613-1619, 202215.

Pessoa De Magalhães Filho RJ, Crusoe E, Riva E, et al.: Analysis of availability and access of anti-myeloma drugs and impact on the management of multiple myeloma in Latin American countries. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 19:e43-e50, 201916.

Treatment for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: Addressing disparities in care. https://www.onclive.com/view/treatment-for-newly-diagnosed-multiple-myeloma-addressing-disparities-in-care17.

Uyl-de Groot CA, Heine R, Krol M, et al.: Unequal access to newly registered cancer drugs leads to potential loss of life-years in Europe. Cancers 12:2313, 202018.

Barrios C, De Lima Lopes G, Yusof MM, et al.: Barriers in access to oncology drugs—A global crisis. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 20:7-15, 202319.

Gay F, Jackson G, Rosiñol L, et al.: Maintenance treatment and survival in patients with myeloma: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol 4:1389, 201820.

Health Expenditure as a Percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in Selected Countries in 202221.

Wu MJ, Zhao K, Fils-Aime F: Response rates of online surveys in published research: A meta-analysis. Comput Hum Behav Rep 7:100206, 202222.

Rajkumar SV: Value and cost of myeloma therapy. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book:662-666, 201823.

Gordan LN, Marks SM, Xue M, et al.: Daratumumab utilization and cost analysis among patients with multiple myeloma in a US community oncology setting. Future Oncol 18:301-309, 202224.

In-Myeloma-New-Drugs-Skyrocketing-Price-Tags. https://ashpublications.org/ashclinicalnews/news/4501/In-Myeloma-New-Drugs-Skyrocketing-Price-Tags25.

Dimopoulos MA, Goldschmidt H, Niesvizky R, et al.: Carfilzomib or bortezomib in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (ENDEAVOR): An interim overall survival analysis of an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 18:1327-1337, 201726.

The ENDEAVOR Trial: A Case Study in the Interpretation of Modern Cancer Trials. https://ascopost.com/issues/june-10-2016/the-endeavor-trial-a-case-study-in-the-interpretation-of-modern-cancer-trials/27.

Sonneveld P, Broijl A, Gay F, et al.: Bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (VRd) ± daratumumab (DARA) in patients (pts) with transplant-eligible (TE) newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM): A multicenter, randomized, phase III study (PERSEUS). J Clin Oncol 37, 2019 (suppl 15; abstr TPS8055)28.

Firestone RS, Mailankody S: Current use of CAR T cells to treat multiple myeloma. Hematology 2023:340-347, 202329.

Johnson & Johnson’s blood cancer therapy gets U.S. FDA approval. https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/johnson-johnsons-blood-cancer-therapy-gets-us-fda-approval-2022-10-25/30.

Fiala MA, Silberstein AE, Schroeder MA, et al.: The dynamics of financial toxicity in multiple myeloma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 23:266-272, 202331.

Guy GP, Yabroff KR, Ekwueme DU, et al.: Healthcare expenditure burden among non-elderly cancer survivors, 2008–2012. Am J Prev Med 49:S489-S497, 201532.

Bestvina CM, Zullig LL, Yousuf Zafar S: The implications of out-of-pocket cost of cancer treatment in the USA: A critical appraisal of the literature. Future Oncol 10:2189-2199, 201433.

Lim S, Wellard C, Moore E, et al.: Real‐world outcomes in relapsed refractory multiple myeloma patients exposed to three or more prior treatments: An analysis from the ANZ myeloma and related diseases registry. Intern Med J 54:773-778, 202434.

Australia and New Zealand Legal and Regulatory Affairs Watchdog Update June 2023. https://www.isctglobal.org/telegrafthub/blogs/lauren-reville/2023/06/13/australia-and-new-zealand-legal-and-regulatory-aff35.

Multiple myeloma patients await MSAC verdict on CAR T-cell therapy to manage blood cancer. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-02-01/myeloma-cancer-patients-wait-regulator-decision-car-t-therapy/103398250. 202436.

Barros LRC, Couto SCF, Da Silva Santurio D, et al.: Systematic review of available CAR-T cell trials around the world. Cancers 14:2667, 202237.

Fatoki RA, Koehn K, Kelkar A, et al.: Global myeloma trial participation and drug access in the era of novel therapies. JCO Glob Oncol 10.1200/GO.22.0011938.

India’s first cell therapy for cancer treatment receives regulatory approval. https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/mumbai-news/indias-first-cell-therapy-for-cancer-treatment-receives-regulatory-approval-101697224829344.html39.

India’s First Homegrown CAR T-Cell Therapy Has Roots. NCI Collaboration. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2024/nexcar19-car-t-cell-therapy-india-nci-collaboration40.

Lythgoe MP, Desai A, Gyawali B, et al.: Cancer therapy approval timings, review speed, and publication of pivotal registration trials in the US and Europe, 2010-2019. JAMA Netw Open 5:e2216183, 202241.

Martin T, Strickland S, Glenn M, et al.: Phase I trial of isatuximab monotherapy in the treatment of refractory multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J 9:41, 201942.

Magen H, Muchtar E: Elotuzumab: The first approved monoclonal antibody for multiple myeloma treatment. Ther Adv Hematol 7:187-195, 201643.

Addressing Challenges in Access to Oncology Medicines. Analytical Report. https://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/Addressing-Challenges-in-Access-to-Oncology-Medicines-Analytical-Report.pdf44.

Varol N, Costa-Font J, McGuire A: Do International Launch Strategies of Pharmaceutical Corporations Respond to Changes in the Regulatory Environment? in McGuire A, Costa-Font J (eds): The LSE Companion to Health Policy. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2012. doi:10.4337/9781781004241.0002245.

Vancoppenolle JM, Franzen N, Koole SN, et al.: Differences in time to patient access to innovative cancer medicines in six European countries. Int J Cancer 154:886-894, 202446.

Grande M, Fernandez J, Putzolu J, et al.: Access and price of cancer drugs: What is happening in France? J Clin Oncol 35 2017 (suppl 15; abstr 6623)47.

Prinja S, Bahuguna P, Pinto AD, et al.: The cost of universal health care in India: A model based estimate. PLoS One 7:e30362, 201248.

Fonseca R, Hinkel J: Value and cost of myeloma therapy-we can afford it. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 38:647-655, 201849.

Generic Drugs: Questions and Answers, US Food and Drug Administration, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/frequently-asked-questions-popular-topics/generic-drugs-questions-answers50.

San-Miguel J, Dhakal B, Yong K, et al.: Cilta-cel or standard care in lenalidomide-refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 389:335-347, 202351.

Rodriguez-Otero P, Ailawadhi S, Arnulf B, et al.: Ide-cel or standard regimens in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 388:1002-1014, 202352.

The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society: FDA's Recent Approval of 2 CAR T-Cell Therapies a ‘Big Step Toward’ Long-Term Control of Myeloma for More Patients, 2024. https://www.lls.org/news/fdas-recent-approval-2-car-t-cell-therapies-big-step-toward-long-term-control-myeloma-more#:∼:text=Search-FDA's%20Recent%20Approval%20of%202%20CAR%20T%2DCell%20Therapies%20a,earlier%20treatment%20of%20multiple%20myeloma53.

Brudno JN, Maus MV, Hinrichs CS: CAR T cells and T-cell therapies for cancer: A translational science review. JAMA 332:1924-1935, 202454.

Medina-Olivares FJ, Gómez-De León A, Ghosh N: Obstacles to global implementation of CAR T cell therapy in myeloma and lymphoma. Front Oncol 14:1397613, 202455.

Atallah R, Ahmed N, Ayoobkhan F, et al.: TACTUM: Trends in access to cellular therapies in multiple myeloma, perspectives of treating versus referring physicians. Transplant Cell Ther 30:925.e1-925.e6, 202456.

García-Guerrero E, Sierro-Martínez B, Pérez-Simón JA: Overcoming chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) modified T-cell therapy limitations in multiple myeloma. Front Immunol 11:1128, 202057.

Gagelmann N, Sureda A, Montoto S, et al.: Access to and affordability of CAR T-cell therapy in multiple myeloma: An EBMT position paper. Lancet Haematol 9:e786-e795, 202258.

Driessen C, Baur K, Heim D, et al.: A national platform and scoring system allocates CAR-T treatment slots for multiple myeloma to patients with high likelihood of complete remission. Blood 142:4701, 2023 (suppl 1)59.

Choudhry P, Galligan D, Wiita AP: Seeking convergence and cure with new myeloma therapies. Trends Cancer 4:567-582, 201860.

Freeman AT, Kuo M, Zhou L, et al.: Influence of treating facility, provider volume, and patient-sharing on survival of patients with multiple myeloma. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 17:1100-1108, 2019