SUDAN'S ONCOLOGY LANDSCAPE BEFORE THE CONFLICT

The foundation of cancer care in Sudan was laid with the establishment of the Radiation and Isotope Centre of Khartoum (RICK), later renamed the Khartoum Oncology Hospital (KOH). This center became the leading hub for cancer treatment, diagnostics, research, and education in the country. Sudan has maintained a pioneering role in cancer care within sub-Saharan Africa since the inauguration of the RICK in 1964., The provision of affordable radiation therapy, a service unavailable in neighboring countries such as Eritrea, Chad, and South Sudan, positioned Sudan as a regional health care hub.

To address the increasing demand for cancer care and to decentralize services, several oncology centers were established across the country. Notable centers included the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in Wad Medani, which became the second-largest cancer treatment facility in Sudan, and additional centers in Merowe, Shendi, and other regions. However, the provision of comprehensive cancer care, including radiotherapy and chemotherapy, remained largely inaccessible to the broader population because of infrastructure limitations and economic constraints.

Before the conflict, Sudan had a relatively well-developed oncology infrastructure compared with other sub-Saharan African countries. KOH was the primary cancer treatment hub, providing comprehensive services, including diagnostics, treatment, early detection programs, and research. The NCI in Wad Medani was the second-largest cancer care center, serving both pediatric and adult patients. Sudan had 15 oncology centers across the country, with five providing radiotherapy services. These centers were located in Khartoum, Wad Medani, Merowe, and Shendi. Of these, only three governmental facilities provided comprehensive cancer care in Sudan, and they were located in the center of the country. Others either lacked at least one major diagnostic/treatment discipline (pathology, radiology, radiotherapy) or provided only chemotherapy-based anticancer treatment.

The Ministry of Health is providing all main chemotherapeutics and other essential cancer medicines for free, and radiotherapy with minimal charges in government hospitals.

In the years leading up to the conflict, Sudan faced a growing challenge from oncologic diseases. Cancer had risen to become the third leading cause of mortality in Sudanese hospitals. The overall 5-year cancer survival rate is 33.75% for all Sudanese patients. According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer, the age-standardized mortality rate (ASMR) for cancer in Sudan is among the higher rates observed in Africa. In 2020, Sudan had an estimated 27,048 new patients and 22,876 cancer-related deaths, with an ASMR of 91.1 per 100,000 population.,

COLLAPSE OF HEALTH CARE INFRASTRUCTURE AND LOSS OF MEDICAL SUPPLIES

The conflict has caused a catastrophic collapse of essential health care infrastructure, severely disrupting oncology services (Table 1). Key institutions such as the KOH and the NCI in Wad Medani are now nonfunctional, drastically limiting cancer care capabilities, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgeries.,,

TABLE 1

The Current Treatment Facilities in Sudan in the Governmental and Private Sectors

| Oncology Center | Location | Type | Services | Current Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khartoum Oncology Hospital (KOH) | Khartoum | Public | Comprehensive oncology services including radiotherapy | Nonfunctional |

| Universal Hospital | Khartoum | Private | Radiotherapy and chemotherapy | Nonfunctional |

| Khartoum Oncology Specialized Centre | Khartoum | Private | medical oncology | Nonfunctional |

| National Cancer Institute (NCI) | Wad Medani Gezira State | Public | Comprehensive oncology services including radiotherapy | Nonfunctional |

| Eldaman Oncology and Radiotherapy Centre | Merowe, Northern State | Private | Radiotherapy and chemotherapy | Functioning with increased patient load |

| Tumour Therapy and Cancer Research | Shendi, River Nile State | Public | Limited radiotherapy and medical oncology | Increased patient load because of displacement |

| East Oncology Centre | El-Gadarif | Public | Chemotherapy and diagnostics | Increased patient load because of displacement |

| Atbra | Atbra | Private | Chemotherapy and diagnostics | Private consultation and chemotherapy |

| Port Sudan Oncology Centre | Port Sudan Red Sea State | Public | Cancer treatment unit providing primarily chemotherapy services | Increased patient load because of displacement |

| White Nile Cancer Centre | Kosti | Public | Cancer treatment unit providing primarily chemotherapy services | Increased patient load because of displacement |

| Dongola Cancer Centre | Dongola, Northern State | Public | Cancer treatment unit providing primarily chemotherapy services | Significant increase in patients' number because of displacement and patients on their way to Egypt |

| Nyala Cancer Centre | Nyala, South Darfur State | Public | Cancer treatment unit providing primarily chemotherapy services | Nonfunctional |

| AlFashir Cancer Centre | AlFashir, North Darfur State | Public | Cancer treatment unit providing primarily chemotherapy services | Nonfunctional |

| Kordofan Cancer Centre | El Obeid, North Kordofan State | Public | Cancer treatment unit providing primarily chemotherapy services | No chemotherapy available. High-risk area |

The crisis has also significantly affected the oncology workforce, with many health care professionals displaced, injured, or killed. Despite these immense challenges, Sudanese doctors, including those in the diaspora, have shown remarkable resilience, attempting to provide care under nearly impossible circumstances. This collapse underscores the urgent need for immediate international support and coordinated action to mitigate the severe impact on patients with cancer.

The conflict in Sudan has severely disrupted medical supply chains, leading to a critical shortage of essential cancer medications, including chemotherapy drugs, hormonal therapies, and targeted therapies. This disruption has drastically affected patient outcomes and the ability of health care professionals to provide necessary treatments. The National Medical Supplies Fund in Khartoum, crucial for distributing these supplies across Sudan, has been vandalized and looted, with significant losses estimated at $500 million US dollars in medical stocks., These events have hampered the delivery and distribution of medical supplies, severely affecting cancer treatment protocols across the country.

DISPLACEMENT AND DISRUPTION OF CARE

The conflict has displaced over 40,000 patients with cancer multiple times, severely disrupting their continuity of care and limiting access to necessary treatments.

Treatment success for childhood cancers such as ALL and Wilms tumor relies on timely and uninterrupted chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and supportive care. Treatment delays in pediatric oncology have been shown to correlate with increased relapse rates and poorer survival outcomes. The forced evacuation of over 275 children undergoing cancer treatment at the NCI in Wad Medani after armed conflict highlights the precarious situation. These children, already immunocompromised due to chemotherapy, faced extreme hardship in displacement settings, lacking access to adequate medical supervision, nutrition, and supportive care.

The systematic review by Cotache-Condor et al on childhood cancer care in low- and middle-income countries identifies key factors leading to treatment delays, including health care infrastructure collapse, limited workforce, and financial constraints. Sudan's war has exacerbated all these factors, rendering even basic cancer care inaccessible. The destruction of the KOH, the NCI, and other major oncology centers has forced thousands of patients to seek care in alternative locations, overwhelming already underresourced facilities. The sudden surge in patient numbers has led to overcrowded facilities, a stark example being the NCI, where 3-4 children were forced to share a single bed.

It is well demonstrated that each 4-week delay in cancer treatment results in a significant increase in mortality across multiple malignancies, including pediatric cancers. Given the near-total cessation of chemotherapy and radiotherapy services in Sudan, the survival of displaced patients with cancer is expected to be severely compromised. Additionally, financial barriers and lack of safe transportation further hinder patients' ability to reach operational oncology centers. Many families cannot afford the cost of travel, lodging, and prolonged treatment in distant hospitals, forcing some to abandon therapy altogether.

The war has disproportionately affected pediatric oncology, but adult patients with cancer are also experiencing significant treatment interruptions. Compounding the crisis, these oncology centers faced a severe shortage of essential cancer medications, including chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and targeted therapies. By August 15, 2023, these centers officially declared a critical lack of these life-saving drugs., This, combined with the mass exodus of oncology professionals because of safety concerns, has left Sudanese patients with cancer in an extremely vulnerable position.

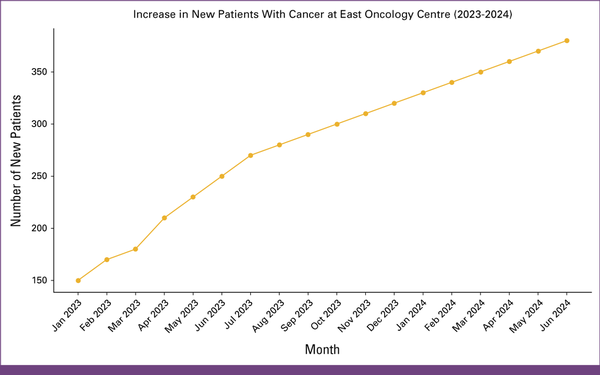

The cessation of oncology services in Khartoum after the outbreak of conflict triggered a dramatic increase in new patients with cancer seeking treatment in nearby states. This surge in patient numbers overwhelmed already strained resources at these facilities. The map (Fig 1) illustrates the different locations of cancer centers in Sudan. Data from the NCI, Tumour Therapy and Cancer Research Centre in Shendi, East Oncology Centre in Elgadarif (Fig 2), and Eldaman Oncology and Radiotherapy Centre in Marawi revealed a substantial rise in new patients with cancer compared with the previous year.

FIG 1

Map of cancer centers in Sudan. Functional: green. Nonfunctional: red. This map depicts the location of cancer centers in Sudan, with color-coding indicating their current operational status. Green markers represent functional centers, while red markers represent centers that are nonfunctional because of the ongoing conflict.

FIG 2

Increase in new patients with cancer at the East Oncology Centre from January 2023 to June 2024. The y-axis represents the number of new patients, while the x-axis represents the month. The gold line visually depicts the trend of increasing patients over time.

This confluence of factors—increased patient load and a critical shortage of medical supplies—placed immense pressure on oncology centers outside Khartoum, severely compromising cancer care for the Sudanese population. The situation worsened further when the conflict extended to Gezira State, leading to the looting and subsequent inoperability of the NCI in Wad Medani.

The Tumour Therapy and Cancer Research Centre in Shendi, for instance, saw the number of new patients with cancer skyrocket from 163 to 791, reflecting the center's struggle to cope with the influx of patients displaced by the conflict. This surge strained available resources, forcing the center to expand its capacity and services under extremely challenging conditions.

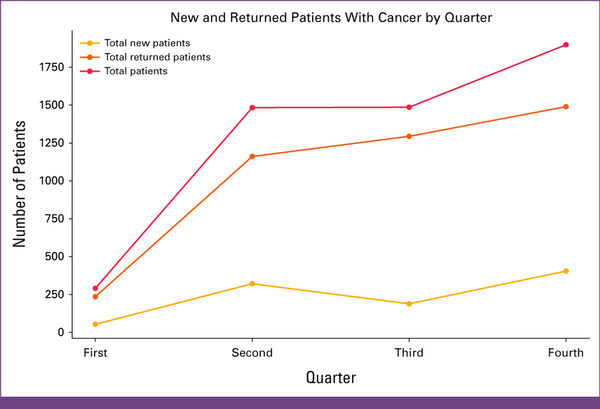

As illustrated in Figure 3, the month of June 2024 alone witnessed a dramatic increase in both new and returning patients with cancer, particularly among female patients, where the number of new patients surged to 563. The data highlight the disproportionate burden placed on centers such as the White Nile Cancer Centre, which must continue to expand their capacity and services despite limited funding, supplies, and health care personnel.

FIG 3

Quarterly distribution of new and returning patients with cancer at the White Nile Cancer Centre in 2023. This graph illustrates the quarterly distribution of patients with cancer at the White Nile Cancer Centre throughout 2023. It shows the number of new patients (patients diagnosed and registered for the first time within each quarter), returning patients (patients previously diagnosed and returning for ongoing treatment or follow-up), and the total number of patients. The x-axis represents the four quarters of the year, while the y-axis indicates the number of patients. The gold line represents the trend in total new patients, the orange line shows total returning patients, and the red line depicts the combined total of new and returning patients for each quarter. These data highlight the increasing patient load at the White Nile Cancer Centre during 2023.

The ongoing conflict has led to a dramatic surge in both new and returning patients with cancer at facilities such as the East Oncology Centre and the White Nile Cancer Centre, as illustrated in Figures 2 and 3.

The East Oncology Centre saw a significant increase in patient numbers, reflecting its critical role in absorbing displaced patients. Similarly, the White Nile Cancer Centre experienced an unprecedented rise in patients, underscoring the dire need for ongoing cancer care in safer regions. These centers were selected for analysis because of their significant patient load increases and their role as key providers of cancer care in regions less affected by the conflict.

The rise in new patients reflects the displacement of populations from conflict zones, while the rise in returning patients highlights the disruption of ongoing treatment regimens at established cancer centers, forcing patients to seek continued care in safer regions.

This surge has placed an overwhelming burden on these peripheral centers, which are already grappling with limited staff, supplies, and funding. For example, the White Nile Cancer Centre saw a dramatic rise of approximately 1,614% in new patients and 1,798% in returning patients, while the NCI nearly doubled its new patients from 1,560 to 2,980.

This crisis underscores the urgent need for increased support and resources for peripheral oncology centers to manage this overwhelming burden and ensure the continuation of cancer care in Sudan.

Financial Constraints and Accessibility Issues

The conflict has severely restricted cancer patients' access to treatment. Many patients cannot afford the high costs associated with travel, accommodation, and treatment, making cancer care a luxury rather than a necessity.

Patients fleeing conflict zones face additional challenges, as the cost and danger of travel make it difficult for them to reach the few operational cancer centers. For example, patients from Al-Gezira State, who previously received treatment at the NCI in Wad Medani, now have to travel to Merowe—a journey that can take up to 2 days and covers over 2,000 km. Patients who used to receive care at centralized facilities in Khartoum are now forced to seek treatment in distant locations such as Merowe, El-Gedarif, and Shendi. The financial burden of such travel, combined with the risks of navigating conflict zones, has forced many patients to forgo treatment altogether.,

Delays in Diagnosis and Treatment

Resources for diagnosing most cancer in Sudan are mainly available in Khartoum, Wad Medani, Shendi (in Northern Sudan), and Port Sudan (in the eastern part of the country). However, these resources are not evenly distributed across the country. Cancer treatment outside Khartuom and Wad Medani experienced a shortage of and materials necessary for cancer diagnosis. The displacement of patients, coupled with the prioritization of acute war-related injuries, can result in significant delays in cancer care, leading to poorer outcomes and increased mortality.,, This prioritization, although necessary for immediate life-saving interventions, results in significant delays for patients with cancer.

THE PATIENTS' PERSPECTIVE

The human cost of the conflict is immeasurable, as patients with cancer and their families face harrowing challenges, including disrupted treatment, fear of violence, and uncertainty about the future, all of which have severely affected their physical and mental well-being.

The disruption of treatment regimens, the constant fear of violence, and the uncertainty surrounding their future have created a profound sense of despair and hopelessness. The voices of these individuals serve as a poignant reminder of the human cost of the conflict and the urgent need for humanitarian assistance and a peaceful resolution.

The stories of patients such as Fatima, a 32-year-old mother of three battling breast cancer, highlight the immense challenges faced by those seeking cancer care in Sudan. Fatima's treatment was abruptly interrupted when the conflict erupted, forcing her to flee her home and seek refuge in a neighboring state. The lack of access to essential medications and the constant fear for her safety have left her feeling helpless and abandoned.

The experiences of children with cancer are particularly heart-wrenching. The disruption of their treatment plans, the separation from their families, and the psychological trauma of living in a war zone have had a profound impact on their lives. The story of Ahmed, a 7-year-old boy with leukemia, illustrates the plight of these young patients. Ahmed's treatment was halted when the hospital where he was receiving care was bombed, forcing him and his family to embark on a perilous journey in search of safety and medical attention.

The urgent need for humanitarian aid, the establishment of safe zones for medical treatment, and the evacuation of critically ill patients are just some of the measures that must be taken to alleviate the suffering of those affected by the conflict. The resilience and courage demonstrated by these individuals in the face of adversity are a testament to the human spirit and a source of inspiration for all those working toward a peaceful and just future for Sudan.

CURRENT EFFORTS AND PROPOSED SOLUTIONS

Raising public awareness through advocacy campaigns, media coverage, and partnerships with influential organizations is crucial to garner international support for Sudanese patients with cancer. Success stories from other conflict zones, such as the evacuation of Ukrainian and Gazan children, can inspire similar efforts in Sudan.

Evacuations are vital for oncology patients in crises, especially for vulnerable groups needing urgent care, but they rely on neighboring countries' capacity and international coordination. Strengthening local health care systems is essential, including rebuilding infrastructure, decentralizing care to safer regions, training health care workers, and securing medical supplies. Global advocacy and funding are crucial to address disparities in cancer care in conflict zones such as Sudan. Integrating cancer care into humanitarian responses and forming partnerships with organizations such as WHO can mobilize resources. While evacuations save lives, sustainable local support ensures equitable and continuous cancer care in crisis settings.

Efforts are being made to address the health care crisis in Sudan. Displaced health professionals from Khartoum and Wad Medani are volunteering, and discussion groups are actively brainstorming solutions to address Sudan's health care crisis. Virtual clinics and telemedicine are being used to reach remote patients. However, these efforts are not sufficient to address the scale of the crisis.

In addition to immediate responses, long-term strategies are essential for building a resilient health care system in Sudan. This includes efficient budget allocation for cancer care, the use of artificial intelligence in pathology laboratories, training health care professionals, and establishing robust medical supply chains. Strengthening health care governance and ensuring compliance with international humanitarian laws are also critical for sustainable development.

EQUITY CONCERNS

The disparity in global attention to cancer care in conflict zones raises profound equity concerns. Although significant efforts have been made to evacuate and provide medical care for patients with pediatric cancer in Ukraine and Gaza,, similar initiatives have been largely absent in Sudan.

WHO emphasizes the importance of integrating cancer care into crisis response frameworks. It propose a global vision for action, highlighting the need for coordinated international efforts to address the disruption of cancer services in conflict zones. Moreover, it advocates for the establishment of emergency cancer care protocols, the mobilization of international resources, and the creation of partnerships between global health organizations, governments, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to ensure continuity of care for patients with cancer in crisis settings.

This framework aligns with the urgent needs in Sudan, where the collapse of oncology services has left thousands of patients without access to life-saving treatments.

Moreover, WHO acted swiftly to extract some of the most vulnerable patients with cancer from Gaza when the war escalated. A special medical evacuation scheme was promptly established within the framework of the European Union Civil Protection Mechanism to organize the medical evacuation of Ukrainian patients to Norway. Additionally, the Supporting Action for Emergency Response initiative facilitated the evacuation of patients with pediatric cancer from Ukraine to the European Union and the United States, enabling them to continue their long-term cancer treatment.

However, it is important to note that the Emergency Response Coordination Centre (ERCC) effort was not limited to Norway. The ERCC, as part of the European Union Civil Protection Mechanism, coordinated the evacuation of Ukrainian patients with cancer to 16 European countries, including Germany, Poland, and Norway, among others. This large-scale, European Union–wide evacuation program successfully transferred 1,385 patients, with a significant proportion being trauma-related injuries and patients with cancer. The ERCC's efforts were supported by a robust international collaboration involving the European Union, WHO, and various NGOs, which ensured the evacuation and treatment of patients with cancer across multiple European countries.

This discrepancy may stem from a combination of geopolitical factors, limited media coverage, and the prioritization of other crises by international organizations. Sudan's protracted conflict and its position in a geopolitically neglected region have contributed to its relative invisibility on the global stage, despite the catastrophic impact on its health care system. To address this inequity, the international community must take immediate and coordinated action. This includes increasing funding for cancer care in Sudan, establishing evacuation programs for critically ill patients, particularly children, and launching global advocacy campaigns to raise awareness of the crisis. Additionally, partnerships with regional organizations, such as the African Organization for Research and Training in Cancer (AORTIC), and international bodies, such as the WHO and United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), are essential to ensure that Sudanese patients with cancer receive the same level of support and attention as those in other conflict zones. By addressing these disparities, the global community can uphold its commitment to health equity and ensure that no patient is left behind, regardless of their location or the geopolitical context of their crisis.

Given the severity of the situation, there is an urgent need for international intervention. Lessons learned from other conflict zones, such as Ukraine and Gaza, can be applied to Sudan. One proposed solution is the immediate evacuation of patients with pediatric cancer to neighboring countries where they can continue their treatment. This would involve identifying the children in need, arranging safe transportation, and ensuring continuity of care in the receiving countries. This would require the coordination of international organizations such as the WHO, UNICEF, and St Jude Hospital, along with regional partnerships with organizations such as the AORTIC.

Additionally, the lack of a coordinated international response, as seen in Ukraine with the MedEvac program, which successfully evacuated 281 patients with cancer to European Union institution, highlights the need for similar structured efforts in Sudan. The MedEvac program in Ukraine was facilitated by robust international cooperation, including the involvement of the European Union, WHO, and NGOs, which ensured the evacuation and treatment of patients with cancer.

The international community's response is crucial not only for Sudan but also for its geopolitically neglected neighbors. The urgency seen in aiding Ukrainian, Palestinian, and Syrian patients with cancer must be mirrored for Sudanese patients. Concerted global efforts are needed to support Sudan's health care system and ensure that patients with cancer receive the necessary care.

Securing international aid and funding is essential for addressing the health care crisis in Sudan. Governments, nongovernmental organizations, and international bodies must collaborate to provide financial support, medical supplies, and logistical assistance. The AORTIC and other regional bodies can play a pivotal role in coordinating these efforts.

Despite these challenges, Sudanese oncologists and health care workers have demonstrated remarkable resilience, continuing to provide care under extreme conditions.

Although immediate evacuation is crucial, there is also a need to strengthen regional cancer centers to handle the influx of displaced patients. Boosting the capacity of existing centers in neighboring countries, and establishing new ones, if necessary, can help mitigate the impact of the conflict. This requires substantial investment in infrastructure, medical supplies, and training for health care professionals.

The international community, including organizations such as the WHO and UNICEF, has a crucial role to play in supporting these efforts. Collaborative initiatives to evacuate patients with cancer to neighboring countries for treatment are urgently needed.,

In conclusion, the ongoing conflict in Sudan has precipitated a catastrophic collapse of cancer care, with displacement and disruption of care emerging as critical humanitarian crises. Over 40,000 patients with cancer have been forcibly displaced, severing their access to essential treatments and continuity of care. This displacement has disproportionately affected vulnerable groups, particularly children, whose treatment regimens have been abruptly interrupted, exacerbating their already dire prognosis. The surge in patient numbers at peripheral oncology centers has overwhelmed limited resources, leading to overcrowded facilities and compromised care quality. The profound equity concerns in global attention to Sudan's crisis are stark. Although significant efforts have been made to evacuate and treat patients with pediatric cancer in Ukraine and Gaza, similar initiatives are conspicuously absent in Sudan. This disparity underscores the geopolitical neglect of Sudan's crisis, leaving its patients with cancer to face abandonment. Urgent, coordinated international action is imperative to address these inequities, including evacuation programs, increased funding, and global advocacy. The international community must prioritize Sudan's cancer care crisis to uphold health equity and prevent further loss of life.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Yasar Ahmed, Awad Mustafa

Administrative support: Awad Mustafa

Collection and assembly of data: Nabeeha Karadawi, Awad Mustafa

Data analysis and interpretation: Yasar Ahmed, Mutasim Abubaker

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/go/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

No potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

1.

Ahmed I, Elhassan MMA, Elnour K, et al.: Collapse of cancer care under the current conflict in Sudan. JCO Glob Oncol 10.1200/GO.24.001442.

Hammad N, Ahmed R: Sudan: Current conflict, cancer care, and ripple effects on the region. Lancet 402:179, 20233.

Elhaj A, Suliman Haj Mukhtar N, Mohammed Ali Elhassan M: How War Has Disrupted the Management of Patients With Breast Cancer in Sudan. https://ascopost.com/news/october-2023/how-war-has-disrupted-the-management-of-patients-with-breast-cancer-in-sudan/4.

Christ SM, Siddig S, Elbashir F, et al.: Radiation oncology in the land of the pyramids: How Sudan continues to push the frontiers of cancer care in eastern Africa. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 110:931-939, 20215.

Health Cluster, WHO. Public Health Situation Analysis: Sudan Conflict. WHO, 2024, pp 29. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/public-health-situation-analysis--sudan-conflict-(03-april-2024)6.

Abasher M, Ahmed H, Abdelateef E: Impact of war on the drug supply for cancer patients in Sudan. J Innov Res 2:44-54, 20247.

Dafallah A, Elmahi OKO, Ibrahim ME, et al.: Destruction, disruption and disaster: Sudan’s health system amidst armed conflict. Confl Health 17:43, 20238.

Maki HAH: General oncology care in Sudan, in Al-Shamsi HO, Abu-Gheida IH, Iqbal F, et al. (eds): Cancer in the Arab World. Singapore, Springer, 2022, pp 251-2649.

Karadawi N, Mohamed S: Cancer, Conflict, and Catastrophe: A Cry for Help From Sudan, a Country at War. ASCO Connection, 2023. https://connection.asco.org/blogs/cancer-conflict-and-catastrophe-cry-help-sudan-country-war10.

Al-Ibraheem A, Abdlkadir AS, Mohamedkhair A, et al.: Cancer diagnosis in areas of conflict. Front Oncol 12:1087476, 202211.

Gafer N, Walker E, Allah MK, et al.: Cancer care in Sudan: Current situation and challenges, in Silbermann M (ed): Cancer Care in Countries and Societies in Transition: Individualized Care in Focus. Cham, Switzerland, Springer International Publishing, 2016, pp 209-21712.

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al.: Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 71:209-249, 202113.

Sharma R, Aashima NM, Fronterre C, et al.: Mapping cancer in Africa: A comprehensive and comparable characterization of 34 cancer types using estimates from GLOBOCAN 2020. Front Public Health 10:839835, 202214.

Alrawa SS, Alfadul ES, Elhassan MMA, et al.: Five months into conflict: Near total collapse of cancer services in Sudan. ecancermedicalscience 17:ed128, 202315.

Badri R, Dawood I: The implications of the Sudan war on healthcare workers and facilities: A health system tragedy. Confl Health 18:22, 202416.

Khogali A, Homeida A: Impact of the 2023 armed conflict on Sudan’s healthcare system. Public Health Chall 2:e134, 202317.

AFP-Agence France: Costly Odyssey for Cancer Care in War-Torn Sudan. AFP News, 2024. https://www.barrons.com/news/costly-odyssey-for-cancer-care-in-war-torn-sudan-5b5bc12d18.

Cotache-Condor C, Grimm A, Williamson J, et al.: Factors contributing to delayed childhood cancer care in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review protocol. Pediatr Blood Cancer 69:e29646, 202219.

Hanna TP, King WD, Thibodeau S, et al.: Mortality due to cancer treatment delay: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 371:m4087, 202020.

Ahmed Y: Enhancing cancer care amid conflict: A proposal for optimizing oncology services during wartime. JCO Glob Oncol 10.1200/GO.23.0030421.

Siddig EE, Eltigani HF, Ali ET, et al.: Sustaining hope amid struggle: The plight of cancer patients in Sudan’s ongoing war. J Cancer Policy 38:100444, 202322.

Nazik H: The cancer situation in Sudan. Cancer Control 21:25-27, 202323.

Preliminary Committee of Sudan Doctors’ Trade Union: Report on the Status of Hospitals. https://www.facebook.com/SudanDoctorsTrandeUnion/posts/pfbid02Aqag458XUbTGEV86vkn6885jPTsW8AQbZeF21KHdYtgp1CBfA8zyE8Tc6y3VJSQDl?rdid=GkMHhoQ6eQiBGSAX24.

Preliminary Committee of the Sudanese Doctors’ Trade Union: List of Names of Murdered Doctors and Health Personnel Since the Beginning of the War in Sudan. https://www.facebook.com/SudanDoctorsTrandeUnion/posts/pfbid02LXaNXmMf2dbe931o5itH7u1ZPjoVYiNPnEn1jvYk3B6c9btZomHroDPX8ThJHMFNl?rdid=Nzk4ZHCahgsawG8q25.

Al Jazeera: Sudan’s forgotten cancer patients: “They’re dying in their homes.” https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2023/8/1/sudans-forgotten-cancer-patients-theyre-dying-in-their-homes26.

BBC News: Cancer patients in Sudan struggle to access care amid conflict, 2023. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-6607220227.

Crerar P: ‘We are dying’: Cancer patients in Sudan plead for help as war rages. The Guardian, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2023/jul/12/we-are-dying-cancer-patients-in-sudan-plead-for-help-as-war-rages28.

Lynch KA, Merdjanoff AA: Impact of disasters on older adult cancer outcomes: A scoping review. JCO Glob Oncol 10.1200/GO.22.0037429.

Casolino R, Sullivan R, Jobanputra K, et al.: Integrating cancer into crisis: A global vision for action from WHO and partners. Lancet Oncol 26:e55-e66, 202530.

Lafraniere S, Green EL: Inside the desperate effort to evacuate young cancer patients from Gaza. N Y Times, 202331.

Agulnik A, Kizyma R, Salek M, et al.: Global effort to evacuate Ukrainian children with cancer and blood disorders who have been affected by war. Lancet Haematol 9:e645-e647, 202232.

Holtan A, Ottesen F, Hoel CC, et al.: Medical Evacuation of Patients from War-Torn Ukraine to Norwegian Hospitals. Tidsskr Den Nor Legeforening, 2023. https://tidsskriftet.no/en/2023/05/perspectives/medical-evacuation-patients-war-torn-ukraine-norwegian-hospitals33.

Mueller A, Salek M, Oszer A, et al.: Retrospective comparative analysis of two medical evacuation systems for Ukrainian patients affected by war. Eur J Cancer 210:114271, 202434.

Huivaniuk I, Kopetskyi V, Ivanykovych T, et al.: Building an effective international medical evacuation program for Ukrainian patients with cancer amid prolonged military conflict. JCO Glob Oncol 10.1200/GO-24-0036335.

Kozhukhov S, Dovganych N, Smolanka I, et al.: Cancer and war in Ukraine. JACC CardioOncology 4:279-282, 202236.

Hovhannisyan A, Philip C, Arakelyan J, et al.: Barriers to access to cancer care for patients from the conflict-affected region of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic: A qualitative study. PLOS Glob Public Health 4:e0003243, 2024