Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity that often persist into adulthood and impair functioning (). Adults with ADHD struggle with demands for autonomy and self-regulation, which can overwhelm their cognitive capacities (). The impairments arising from these challenges are magnified when individuals leave home to attend university, where they are required to manage their own schedules, assignments, and finances with little parental supervision or other imposed structure (). Procrastination is one of the commonly reported difficulties among university students with ADHD (). Defined as the voluntary delay of an intended course of action despite expecting to be worse off for the delay (), procrastination is associated with poor academic achievement () and increased depressive symptoms (). Procrastination should be considered a target of treatment for adult ADHD ().

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for adults with ADHD often addresses time management (; ) and organization skills (), which can help reduce procrastination. Common behavioral strategies to improve task completion include segmenting of large tasks into manageable pieces and self-rewarding adaptive behaviors such as engaging in tasks experienced as aversive (). Cognitive restructuring to disrupt maladaptive thinking patterns may include an analysis of the pros and cons of procrastination (; ). However, reducing procrastination is not always made an explicit treatment goal, instead of being addressed as part of general ADHD symptom reduction ().

A recent meta-analysis identified 12 studies that examined the effects of psychosocial treatment targeting procrastination (), yielding a moderate effect size. Four of the included studies focused on CBT. These programs incorporated both behavioral and cognitive strategies including prioritizing of tasks, stimulus control, organization and planning, task segmentation, and cognitive restructuring around beliefs about procrastination. Although similar to strategies emphasized in the treatment of college students with ADHD (; ), none of these studies targeted this population.

Additional research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of procrastination-focused CBT for university students diagnosed with ADHD or with elevated ADHD symptom levels. In addition to supporting academic performance, reducing the daily impairment resulting from procrastination will likely lead to improved mood and life satisfaction. Treating procrastination early in the students’ academic career will help minimize secondary symptoms and negative impairments (), while focusing on skills directly related to problems occurring in daily life should improve intervention effectiveness (; ).

A brief six-session online CBT program, targeting procrastination among young university students with ADHD symptoms, was developed for the current study by the first and last authors (see Supplemental material 1; see PDF view for program details). This Japanese language program is largely based on information and materials available in and at . These materials were utilized with the original authors’ knowledge and permission. In addition, the psychoeducation and CBT strategies in the current program addressed the stronger tendency of those with ADHD to act to obtain immediate reward (; ) and avoid aversive experiences (; ; ).

We evaluated this brief procrastination-focused CBT program with Japanese university students using a single-case, repeated measures AB design. This approach was chosen as procrastination behaviors can fluctuate depending on life events (e.g., a deadline for a paper) and specific intervention sessions. Baseline measures of procrastination and mood were established through having participants complete twice-weekly ratings for approximately 3 weeks. This was followed by a 6-week intervention period, during which they continued with twice-weekly ratings. An interrupted time series analysis was conducted to examine the changes during the baseline versus intervention periods. In addition, the relationship between changes in the procrastination behaviors and in depressive symptoms and life satisfaction were examined. It was hypothesized that participation in the intervention would change the pattern of the procrastination behaviors from their initial trajectory identified through repeated baseline assessments. The reduction in procrastination behaviors was expected to be associated with decreased depressive symptoms and increased life satisfaction.

METHODS

Participants and Recruitment

Participants were undergraduate and postgraduate students studying at a private university in an urban area in Japan. They were recruited through the university’s website and classes. Interested students were invited to complete online forms to determine if they were eligible to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria were (a) current difficulties with procrastination, (b) exceeding the cutoff on the ADHD screening scale (Adult ADHD Self Report Scale; ASRS Part A), and (c) being a native Japanese speaker without visual or hearing impairments. Exclusion criteria were (a) currently receiving pharmacological or nonpharmacological psychiatric treatment, (b) extreme sleep deprivation or fatigue, or (c) alcohol intake in the 12 hours prior to the preintervention assessment. Twenty-nine participants aged 19–25 years (17 females, mean age = 20.76 years, SD = 1.72) were enrolled in the study (See Supplemental material 2). One participant had a diagnosis of ADHD but was not receiving any treatment at the time of study enrollment. No other participants reported having any psychiatric disorder. Among those enrolled, the following participants were excluded from the data analysis for the following reasons: declined to start the intervention (n = 1), dropped out due to illness (n = 1) or could not be contacted for more than 1 month during the intervention (n = 1), and 0% intervention homework completion rate (n = 2). The final dataset included 24 participants (15 females, mean age = 20.42 years, SD = 1.50). Participants received 8,000 yen as a gratuity upon completion of postintervention measures.

Measures

Participants were asked to complete the following assessment measures.

Measures Before, During, and After the Intervention

The General Procrastination Scale (GPS), a 13-item questionnaire (), was used to measure self-reported procrastination behavior in daily life ().

Two subscales from the Pure Procrastination Scale (PPS), decisional procrastination (three items) and timeliness (four items), were used as additional measures of procrastination (; ). The decisional procrastination scale measures behaviors before deciding on an action (e.g., wasting a lot of time on trivial matters before making a final decision), and the timeliness scale measures behaviors before and after the deadline (e.g., not finishing tasks on time). Both GPS and PPS collect responses using 5-point Likert scales, with higher scores typically representing more severe procrastination behaviors (four items on the GPS are reverse scored). The reliabilities of the Japanese version of both the GPS (Cronbach’s coefficient α = .87; ) and the PPS (Cronbach’s coefficient α of decisional procrastination = .80, α of timeliness = .83) are good ().

The short version of the Profile of Mood States (POMS) 2nd Edition, a 30-item questionnaire that also uses 5-point Likert scales, was used to assess mood (; ). A Total Mood Disturbance score The reliability of the subscales on was calculated by summing the five subscales (tension–anxiety, depression–dejection, anger–hostility, fatigue–inertia, and confusion–bewilderment) and then subtracting the vigor–activity subscale score. The reliability of the subscales on the Japanese version of POMS is good to excellent (Cronbach’s coefficient α = .76–.95; ).

Pre– and Post-Intervention Measures

The ASRS Part A-v1.1 () was used to screen for ADHD symptoms (). It includes six items, four measuring inattention and two measuring hyperactivity/impulsivity. Endorsing four or more items as “often” or “very often” is considered highly consistent with a clinical level of ADHD in adults (), and this was used as the inclusion criteria for the study. Cronbach’s coefficient α for the Japanese version of ASRS is α = .89 ().

Two measures of depression were included to assess participants’ mood pre- and post-intervention. The nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), utilizing 4-point Likert scales, was used to measure depressive symptoms (, ). Total scores range from 0 to 27, with scores 0–4 indicating no, 5–9 mild, 10–14 moderate, 15–19 moderate–severe, and 20–27 severe depressive symptoms, respectively. The reliability of Japanese version of PHQ is high (Cronbach’s coefficient α = .91; ).

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale is a 20-item measure which uses 4-point Likert scales (; ). The CES-D is made up of four subscales: physical symptoms and psychomotor inhibition, depressive affect, positive affect (low), and interpersonal problems. Total scores range from 0 to 60, with a score of 16 or more indicating a risk of clinical depression. The reliability of Japanese version of CES-D is good (Cronbach’s coefficient α = .84; ).

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) was used to measure life satisfaction (; ). The SWLS consists of five items, e.g., “In most ways my life is close to my ideal.” Participants answered on a 7-point scale from 1 not at all applicable to 7 very applicable. The higher the total score, the more satisfied the participant feels with their life. The reliability of Japanese version of SWLS is high (Cronbach’s coefficient α = .88; ).

Post-Intervention Measure

The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8 (CSQ-8J) was used to measure the participants’ satisfaction with the intervention (; ). The CSQ-8J consists of eight items, each rated on a 4-point Likert scale. A higher total score indicates greater satisfaction with the program. The reliability of Japanese version of CSQ-8J is good (Cronbach’s coefficient α = .81; ).

Ethical approval.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Waseda University Ethics Review Committee on Research with Human Subjects (approval number: 2021–177). All participants were volunteers who provided written informed consent and were advised they that could terminate their participation in the study at any time without penalty.

Procedure

Screening

Participants were recruited through the Waseda University’s homepage and classes. Students interested in the study were requested to email the first author. Upon receipt of emails, expressing interest in participating, they were sent more detailed information about the study (via return email). Those who remained interested were asked to complete a Google Form answering questions about the study inclusion and exclusion criteria. From their responses, the researchers determined their eligibility to take part in the study. All potential participants were emailed whether or not they were eligible to participate in the study.

Baseline

After being accepted into the research program, the participants were asked to complete the preintervention questionnaires (ASRS, GPS, PPS, CES-D, PHQ, and SWLS) at the university. Following completion of the measures, participants entered the baseline period. Participants were asked to complete the baseline questionnaires online twice per week (with 2–3 days between administration) for 3 weeks: the two procrastination questionnaires (GPS and PPS) and the mood state questionnaire (POMS; ). At the end of the baseline period, the participants began the 6-week intervention delivered individually via Zoom. During the intervention period, they continued to complete the procrastination and mood questionnaires twice per week. One week after completing the intervention, the participants were asked to complete the preintervention questionnaires the second time together with the CSQ8-J.

Intervention

After the baseline phase, participants began the intervention phase of the study. During this phase, they were asked to provide twice-weekly reports of procrastination and mood states during the baseline phase. One week after completing the intervention, participants answered the postintervention questionnaires (i.e., the preintervention questionnaires and CSQ8-J).

The intervention consisted of six 60-minute individual sessions. Each participant met with a clinical psychologist (first author) online once a week. The first and second sessions consist of psychoeducation on, and functional analysis of, procrastination behavior to increase understanding of triggers and short- and long-term consequences as well as motivation for change. The third session focuses on teaching behavioral skills, such as time management, prioritizing, stimulus control, task segmentation, and use of self-praise for achieving each segment of a task. The fourth session aims to help identify and reduce maladaptive thoughts related to procrastination and replace them with adaptive thoughts to induce appropriate behavioral activation. The fifth session includes discussions of life values and goals, being aware of them to change current behaviors, and improving self-acceptance while reducing self-criticism. In the final session, behavioral and cognitive strategies are reviewed, and a plan created to prevent relapse.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS statistics 26.0 () and R (version 4.3.3).

An interrupted time series (ITS) analysis was conducted to examine the changes in the procrastination and mood for all participants. First, data were centered on each participant’s score on the first assessment during the baseline phase. Autocorrelation and stationarity of the data were checked (Supplemental material 3; see PDF view); the augmented Dickey–Fuller test revealed that the time series data were not stationary, and autocorrelation functions (ACF) and partial-ACF (PACF) plots together with the Durbin–Watson test indicated the data were autocorrelated (Supplemental material 3; see PDF view). Given these results, ITS analysis using an autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model was employed to examine whether the trajectory of procrastination behaviors (GPS and PPS) and mood (POMS) changed significantly in response to the intervention, that is, if it deviated significantly from the estimated trajectory based on the baseline phase data (i.e., the counterfactual data).

Wilcoxon’s signed rank tests and t tests were used to examine within-subjects changes in pre- and post-intervention scores on the measures of depressive symptoms and life satisfaction. Spearman’s rank coefficients were calculated to assess if changes in procrastination from pre- to post-intervention were associated with changes in depressive symptoms and life satisfaction.

RESULTS

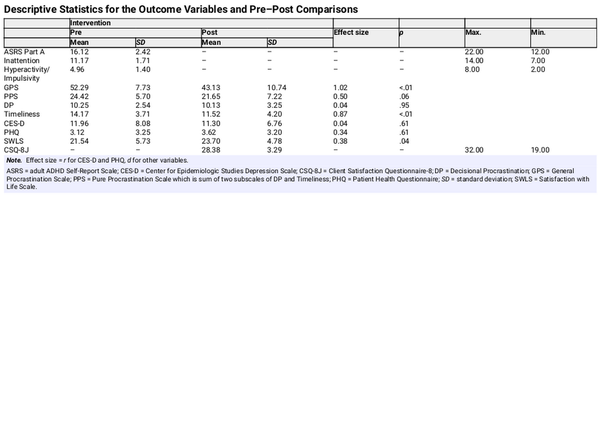

Descriptive Data

Descriptive statistics for the pre- and post-outcome variables together with intervention satisfaction are presented in Table 1. As expected, high levels of inattention (M = 11.17, SD = 1.71) and moderate levels of hyperactivity/impulsivity (M = 4.96, SD = 1.40) were reported on Part A of the ASRS. The participants’ satisfaction with the intervention was high as indicated by CSQ-8J scores (M = 28.38, SD = 3.29).

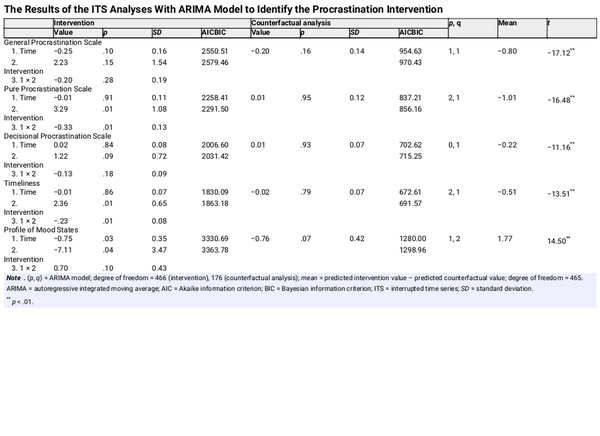

ITS Analysis

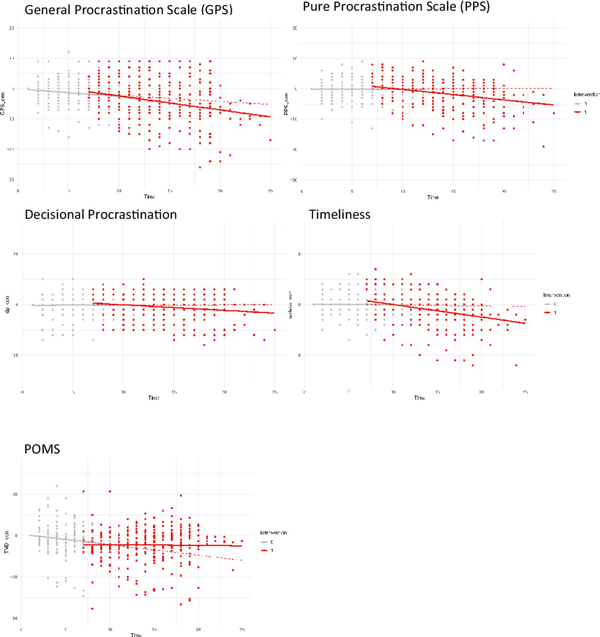

The results of ITS with ARIMA models of procrastination and mood from baseline to postintervention are presented in Table 2 and Figure 1. A significant time × intervention effect was found for the PPS overall score (coefficient value = −.33, p < .05) and the timeliness subscale (coefficient value = −.23, p < .01). The effects for the GPS were not significant. There was also a significant main effect for the POMS, with the score decreasing with both time (coefficient value = −.75, p < .05) and intervention (coefficient value = −7.11, p < .05). A comparison of the intervention phase data with the counterfactual data indicated that the procrastination intervention significantly changed the course of the procrastination behaviors (GPS t(465) = −17.12, p < .01, 95% CI [–.89, –.71]; PPS t(465) = −16.48, p < .01, 95% CI [–1.13, –.89]; decisional procrastination t(465) = −11.16, p < .01, 95% CI [–.25, –.18]; timeliness t(465) = −13.51, p < .01, 95% CI [–.59, –.44]), and also mood (POMS, t(465) = 14.50, p < .01, 95% CI [1.53, 2.01]). All the procrastination indicators showed improvement. However, mood worsened compared to the baseline.

Interrupted time series analysis and counterfactual analysis for each variable.

Note. The data showed all participants’ score. Time means the point of participants answering all variables twice a week. All of variables were centered on each participant’s score on the first assessment during the baseline phase. Dotted red lines indicate the results of counterfactual analyses.

POMS = Profile of Mood States.

Pre- Versus Post-intervention Changes in Depressive Symptoms and Life Satisfaction

Wilcoxon’s signed rank test and t test were used to examine within-subjects changes in pre- and post-intervention questionnaire scores (Table 1). There was a significant increase in the quality of life, SWLS (t(22) = −2.15, p = .04, 95% CI [–4.95, –0.09], d = −0.38). However, no significant changes were observed in the depressive symptoms as measured by the PHQ-9 (V = 91.00, p = .61, r = 18.58) and the CES-D (V = 142.50, p = .61, r = 29.09).

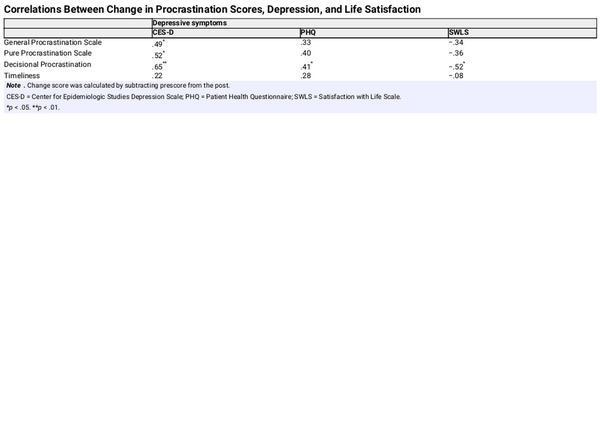

Association Between Changes in Procrastination, Depressive Symptoms, and Life Satisfaction

Change scores for procrastination behaviors (GPS and PPS), depressive symptoms (CES-D and PHQ), and life satisfaction (SWLS) were calculated by subtracting the pre-intervention scores from the post-intervention scores (Table 3). Change in CES-D depressive symptoms correlated significantly with changes in the procrastination scores, GPS (ρ = .49, p = .01) and PPS (ρ = .52, p = .01). Changes on the decisional procrastination subscale of the PPS also correlated significantly with the changes in the depressive symptoms positively (CES-D [ρ = .65, p < .01] and PHQ [ρ = .41, p = .04]) and quality of life negatively (SWLS [ρ = −.52, p = .01]).

DISCUSSION

The current study examined the effects of procrastination-focused CBT on the procrastination behaviors and mood of university students with elevated levels of ADHD symptoms. The results indicate that the intervention altered the trajectory of the students’ procrastination behaviors and mood in a positive direction, and the students reported their life satisfaction was higher after completing the intervention. While the intervention did not show a change in depressive symptoms from pre- to post-intervention, increased life satisfaction was reported.

The estimated trajectory of the students’ procrastination behaviors changed in a positive direction from baseline through intervention. It is thought that in-session discussions with the therapist together with homework to monitor their schedule and task completion may have helped students become more aware of their procrastination behaviors. The intervention also likely helped them initiate, and sometimes follow through on, tasks. However, their reports indicated that they still had difficulty deciding to initiate tasks and took time in doing so.

The shift in the trajectory of the participants’ procrastination behaviors from the predicted (counterfactual) pattern supports the conclusion that the intervention changed their behaviors and that any decrease was not simply the effects of time/repeated measures as previously suggested by . These researchers showed a reduction in procrastination over repeated measures in the absence of any intervention. In the current study, we demonstrate the decrease in procrastination behaviors accelerated from baseline to intervention. The effects of the current study need to be confirmed in a randomized control trial.

In contrast to the positive effects of the intervention on procrastination behaviors, the intervention did not improve participants’ mood beyond baseline changes. As indicated in the figure, POMS scores declined during the baseline period but were stable during the intervention. Overall levels of depression were low, reducing the possibility of change. The initial small decrease in scores at the beginning of baseline recordings may reflect anticipation of improvements in procrastination by the participating students, which may have lifted their mood. It is also possible that the work required by the students during the intervention may have prevented further improvements in their mood.

With a reduction in procrastination behaviors, students’ reported life satisfaction also improved. This is an important effect, as procrastination is one of the commonly reported difficulties among university students with ADHD () and is related to poor academic achievement (). Young adulthood is an important developmental period that can affect the life trajectory ().

Conversely depressive symptoms were not affected by the intervention. This may be due to the very low depressive symptom scores of more than half of the participants (scores of 0–4 on PHQ and below the cutoff point on CES-D) at the beginning of the study. This was surprising as high levels of procrastination are often associated with increased levels of depression and stress (). The current study excluded students who were currently receiving psychiatric treatment. In addition, participants in the study needed to be motivated to complete repeated assessments and a 6-week intervention; this may have resulted in the further exclusion of those experiencing high levels of depressive symptoms. Although a decrease in depressive symptoms was associated with a decrease in reported difficulties in deciding to initiate tasks, given the initially low levels of depressive symptoms, this may not be clinically meaningful. Future studies should include participants with a wider range of symptom presentation to examine the effects of procrastination-focused CBT on depressed mood.

By using the repeated measures design and interpreted time series analysis, the current study was able to capture the intervention effects over time while accounting for possible fluctuations in procrastination behaviors. Procrastination is also context dependent. Based on the stress context vulnerability model of procrastination (), people who face high-stress contexts tend to increase procrastination behavior by decreasing both coping resources and tolerance for negative states. Therefore, this study might have captured more of the trajectories of procrastination that were affected by the events surrounding the participants. Unfortunately, we cannot test this hypothesis with the current data; this requires a control group design.

While the present study offers some important new findings regarding the management of procrastination in student populations at risk for ADHD, its limitations need to be acknowledged. First, participants entered the study on different days (over 6 months), and the intervention duration varied depending on the participants’ availability to attend the Zoom sessions with the psychologist. Starting all participants at one time and having the same number of data points would have allowed for better examination of the pattern of behavioral changes in response to each session while controlling for environment demands (i.e., the period of the academic year). Second, the same person delivered the intervention and administered the assessments, which may have influenced the participant responses to the assessment. However, the procrastination questionnaires were administered online, which likely reduced any such effects. In clinical settings, the same clinicians usually conduct evaluations and provide treatment. Third, two participants had a 0% homework implementation rate, and one could not be contacted for over a month. While they were not included in the analysis, these incidents were not insignificant. For individuals with procrastination tendencies, these behaviors are perhaps not unsurprising. Procrastination interventions for those with ADHD likely need to incorporate more frequent reminders and reinforcements to complete homework, or segmenting of homework into smaller chunks may improve the completion rate. Fourth, the duration of the intervention was short and consisted of six sessions only. While such a brief intervention may be attractive to university students and increase the likelihood of them completing the entire program, a longer intervention, additional sessions, or having booster sessions could have yielded stronger and more consistent effects on participants’ decision-making process related to task initiation and the timely completion of tasks. Previous studies employed longer duration of the intervention and showed a significant effect on procrastination (e.g., 10 sessions in ; ). Finally, examination of group effects using a randomized control trial would provide stronger evidence for the effects of the procrastination-focused intervention beyond treatment as usual, other forms of intervention, placebo effects, or other factors that contributed to the current results. There was some indication in the current study that the anticipation of entering treatment may have changed participants’ procrastination behaviors and mood during the baseline period.

CONCLUSIONS

Brief procrastination-focused CBT, delivered online, changed the trajectory of students’ procrastination behaviors relative to their baseline behaviors, especially the timeliness aspect of procrastination. The current study is one of a very small number examining the effects of the procrastination-focused CBT among adults demonstrating some symptoms of ADHD and the first to use an AB design to consider fluctuations in procrastination over time. It is also the first study to examine the effects of this procrastination intervention in Japanese university students. In countries like Japan, where mental health treatment is not easily accessed or accepted, an intervention focused on a specific challenge (than a disorder), and delivered online, could reach and help many young people who are struggling.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5-TR. American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

- Anastopoulos A. D., & King K. A. (2015). A cognitive-behavior therapy and mentoring program for college students with ADHD. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(2), 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.01.002

- Barnard-Brak L., Watkins L., & Richman D. (2021). Optimal number of baseline sessions before changing phases within single-case experimental designs. Behavioural Processes, 191(104461), 104461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2021.104461

- Center for Clinical Interventions. (2024). Procrastination. https://www.cci.health.wa.gov.au/Resources/For-Clinicians/Procrastination

- Diener E., Emmons R. A., Larsen R. J., & Griffin S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- DuPaul G. J., Weyandt L. L., O’Dell S. M., & Varejao M. (2009). College students with ADHD: Current status and future directions. Journal of Attention Disorders, 13(3), 234–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054709340650

- Eddy L. D., Dvorsky M. R., Molitor S. J., Bourchtein E., Smith Z., Oddo L. E., Eadeh H.-M., & Langberg J. M. (2018). Longitudinal evaluation of the cognitive-behavioral model of ADHD in a sample of college students with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 22(4), 323–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054715616184

- Eddy L. D., Will H. C., Broman-Fulks J. J., & Michael K. D. (2015). Brief cognitive behavioral therapy for college students with ADHD: A case series report. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(2), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.05.005

- Halfon N., Forrest C. B., Lerner R. M., & Faustman E. M. (2018). Handbook of life course health development. In N. Halfon, C. B. Forrest, R. M. Lerner, & E. M. Faustman (.), Handbook of life course health development. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47143-3_15

- Hartung C. M., Canu W. H., Serrano J. W., Vasko J. M., Stevens A. E., Abu-Ramadan T. M., Bodalski E. A., Neger E. N., Bridges R. M., Gleason L. L., Anzalone C., & Flory K. (2022). A new organizational and study skills intervention for college students with ADHD. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 29(2), 411–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2020.09.005

- Hayashi J. (2007). Development of Japanese version of general procrastination scale. Japanese Journal of Personality, 15(2), 246–248. https://doi.org/10.2132/personality.15.246

- Heuchert J. P., & McNair D. M. (2012). Profile of mood states 2nd EditionTM. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t05057-000

- IBM Corp. (2019). IBM SPSS statistics for windows (version 26.0). IBM Corp.

- Johansson F., Rozental A., Edlund K., Côté P., Sundberg T., Onell C., Rudman A., & Skillgate E. (2023). Associations between procrastination and subsequent health outcomes among university students in Sweden. JAMA Network Open, 6(1), e2249346. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.49346

- Kadono Z. (1994). A Japanese version of the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS). In Poster session presentation at the meeting of the Japanese association of educational psychology, Kyoto, Japan.

- Kaneko Y., Ikeda H., Fujishima Y., Umeda A., Oguchi M., & Takahashi E. (2022). Examination of the reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the pure procrastination scale. Japanese Journal of Personality, 31(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.2132/personality.31.1.1

- Kessler R. C., Adler L., Ames M., Demler O., Faraone S., Hiripi E., Howes M. J., Jin R., Secnik K., Spencer T., Ustun T. B., & Walters E. E. (2005). The World Health Organization adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): A short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychological Medicine, 35(2), 245–256. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291704002892

- Knouse L. E., & Fleming A. P. (2016). Applying cognitive-behavioral therapy for ADHD to emerging adults. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 23(3), 300–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2016.03.008

- Krause K., & Freund A. M. (2014). Delay or procrastination–A comparison of self-report and behavioral measures of procrastination and their impact on affective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 63, 75–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.050

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R. L., & Williams J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Larsen D. L., Attkisson C. C., Hargreaves W. A., & Nguyen T. D. (1979). Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: Development of a general scale. Evaluation and Program Planning, 2(3), 197–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6

- Lay C. H. (1986). At last, my research article on procrastination. Journal of Research in Personality, 20(4), 474–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-6566(86)90127-3

- Nakashima M., Inada N., Tanigawa Y., Yamashita M., Maeda E., Kouguchi M., Sarad Y., Yano H., Ikari K., Kuga H., Oribe N., Kaname H., Harada T., Ueno T., & Kuroki T. (2022). Efficacy of group cognitive behavior therapy targeting time management for adults with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Japan: A randomized control pilot trial. Journal of Attention Disorders, 26(3), 377–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054720986939

- Pfizer. (2024). Welcome to the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) screeners. https://www.phqscreeners.com/select-screener

- Przetacka J., Droździel D., Michałowski J. M., & Wypych M. (2022). Self-regulation and learning from failures: Probabilistic reversal learning task reveals lower flexibility persisting after punishment in procrastinators. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 151(8), 1942–1955. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0001161

- Radloff L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306

- Ramsay J. R. (2019). Rethinking adult ADHD: Helping clients turn intentions into actions (Vol. 213). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000158-000

- Ramsay J. R., & Rostain A. L. (2007). Psychosocial treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: Current evidence and future directions. Professional Psychology, 38(4), 338–346. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.38.4.338

- Rozental A., Bennett S., Forsström D., Ebert D. D., Shafran R., Andersson G., & Carlbring P. (2018). Targeting procrastination using psychological treatments: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1588. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01588

- Rozental A., & Carlbring P. (2013). Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for procrastination: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Research Protocols, 2(2), e46. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.2801

- Rozental A., Forsell E., Svensson A., Andersson G., & Carlbring P. (2015). Internet-based cognitive-behavior therapy for procrastination: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(4), 808–824. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000023

- Safren S. A., Sprich S., Chulvick S., & Otto M. W. (2004). Psychosocial treatments for adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 27(2), 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0193-953X(03)00089-3

- Safren S. A., Sprich S. E., Perlman C. A., & Otto M. W. (2017). Mastering your adult ADHD: A cognitive-behavioral treatment program, client workbook. Oxford University Press.

- Shima S., Shikano T., Kitamura T., & Asai M. (1985). A new self-report depression scale. Psychiatry, 27, 717–723. https://doi.org/10.11477/mf.1405203967

- Sirois F. M. (2023). Procrastination and stress: A conceptual review of why context matters. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 5031. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20065031

- Solanto M. V., Marks D. J., Wasserstein J., Mitchell K., Abikoff H., Alvir J. M. J., & Kofman M. D. (2010). Efficacy of meta-cognitive therapy for adult ADHD. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(8), 958–968. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081123

- Sonuga-Barke E. J. S. (2003). The dual pathway model of AD/HD: An elaboration of neuro-developmental characteristics. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 27(7), 593–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.08.005

- Stead R., Shanahan M. J., & Neufeld R. W. J. (2010). “I’ll go to therapy, eventually”: Procrastination, stress and mental health. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(3), 175–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.03.028

- Steel P. (2007). The nature of procrastination: A meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 65–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.65

- Steel P. (2010). Arousal, avoidant and decisional procrastinators: Do they exist? Personality and Individual Differences, 48(8), 926–934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.02.025

- Tachimori H., & Ito H. (1994). Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of client satisfaction questionnaire. Seishin Igaku (Psychiatry), 41, 711–717. https://doi.org/10.11477/mf.1405905056

- Takeda T., Tsuji Y., & Kurita H. (2017). Psychometric properties of the Japanese version of the Adult Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Self-Report Scale (ASRS-J) and its short scale in accordance with DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 63, 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2017.02.011

- Tsuboi H., Takakura Y., Tsujiguchi H., Miyagi S., Suzuki K., Nguyen T. T. T., Pham K. O., Shimizu Y., Kambayashi Y., Yoshida N., Hara A., & Nakamura H. (2021). Validation of the Japanese version of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale-revised: A preliminary analysis. Behavioral Sciences, 11(8), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11080107

- Umegaki Y., & Todo N. (2017). Psychometric properties of the Japanese CES-D, SDS, and PHQ-9 depression scales in university students. Psychological Assessment, 29(3), 354–359. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000351

- van der Oord S., & Tripp G. (2020). How to improve behavioral parent and teacher training for children with ADHD: Integrating empirical research on learning and motivation into treatment. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 23(4), 577–604. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-020-00327-z

- Wypych M., Michałowski J. M., Droździel D., Borczykowska M., Szczepanik M., & Marchewka A. (2019). Attenuated brain activity during error processing and punishment anticipation in procrastination - a monetary Go/No-go fMRI study. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 11492. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48008-4

- Yokoyama K., & Watanabe K. (2015). Profile of mood states (2nd edition.). Kanekosyobou.

- Zhang Y. Y., Xu L., Rao L. L., Zhou L., Zhou Y., Jiang T., Li S., & Liang Z. Y. (2016). Gain-loss asymmetry in neural correlates of temporal discounting: An approach-avoidance motivation perspective. Scientific Reports, 6, 31902. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep31902