Introduction

Breast cancer survival has improved over decades, and early-stage treatment contributes most to mortality reduction. For the most common subtype, estrogen receptor–positive and/or progesterone receptor–positive and human epidermal growth factor 2–negative, endocrine therapy is the primary and often the only adjuvant systemic therapy, as chemotherapy use has declined. Compared with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation, endocrine therapy is less intensive and constitutes the survivorship phase of treatment. However, its multiyear duration challenges adherence. Furthermore, recent trials have shown recurrence-free survival benefits from more intensive endocrine regimens, including ovarian suppression to enable use of an aromatase inhibitor for premenopausal women, and addition of a CDK 4/6 inhibitor for 2 or 3 years with stage II-III disease. There is growing evidence for longer duration of endocrine therapy (7-10 vs 5 years),, with guidelines advising 10 years for patients with higher disease stage. Yet little is known about which patients choose more than 5 years of endocrine therapy or how these decisions are made. We conducted a population-based survey study to understand patients’ use of and decisions about extended endocrine therapy, aiming to inform patient-clinician shared decision making.

We sent a follow-up questionnaire to evaluate treatment experiences and decision making at approximately 6 years postdiagnosis among 2502 participants in the iCanCare study of women diagnosed with breast cancer in 2014-2015 who were identified from the population-based Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registries of Georgia and Los Angeles County, California. We hypothesized that few women with stage I breast cancer would choose extended endocrine therapy, and decision making would vary with clinical, demographic, and psychosocial factors.

Methods

Study population

The iCanCare Study is a population-based, longitudinal survey study of women with early-stage breast cancer and their clinicians. As detailed previously, women ages 20-79 years who were newly diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer (stages 0-II) in 2014-2015 as reported to the SEER registries of Georgia and Los Angeles County were surveyed. Black, Asian, and Hispanic women were oversampled. Women were ineligible if they had stages III or IV breast cancer, had tumors larger than 5 centimeters, or could not complete a questionnaire in English or Spanish (n = 258). The median time from breast cancer diagnosis to baseline survey completion was 7.8 months (25%-75%; range = 5.6-10.1 months).

A total of 2502 respondents who completed baseline surveys (68% baseline response rate) were selected for a follow-up survey broadly examining women’s health-care experiences since breast cancer diagnosis (see Figure S1 for inclusion and exclusion criteria and study flow diagram). Women were ineligible for follow-up if they were deceased (n = 108) or too ill or otherwise unable to participate (n = 33), and the remaining eligible baseline survey respondents (n = 2361) were sent a follow-up survey in 2021-2022. The median time from cancer diagnosis to follow-up survey completion was 83.6 months (25%-75%, range = 53.1-86.8 months). Eligible women were sent a packet of follow-up survey materials, including $20 cash incentive up front, with an option to complete the survey online. We used a modified Dillman approach to increase response, including extensive telephone follow-up, reminder letters, and remailing of survey packets to nonrespondents. Of the 2361 eligible women, 1412 completed the follow-up survey, for a 60% follow-up response rate. Survey responses were merged with SEER clinical data, and a de-identified analytic dataset was created. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines and was approved by the University of Michigan institutional review board (HUM00163318) and the institutional review boards of SEER registries (Georgia: STUDY00001209; Los Angeles: HS-13-00397). We restricted the analytic sample to those without a new cancer event (recurrence or second primary cancer, except for nonmelanoma skin cancer), with clinical indication to consider extended endocrine therapy beyond 5 years (stage I or higher estrogen receptor–positive and/or progesterone receptor–positive breast cancer and had already taken endocrine therapy for at least 5 years or were still taking endocrine therapy at follow-up) and who had made a decision about whether to continue beyond 5 years., This resulted in a final analytic sample of 557 women of which 376 had stage I and 181 had stage II disease (Figure S1).

Measures

Questionnaire content was developed based on a conceptual framework, informed by the National Cancer Institute Quality of Survivorship Care Framework that describes best practices of cancer survivorship care and by the Health Belief Model, which posits that health behaviors are a function of an individual’s perceived benefits, barriers, and cues to action (such as the role of others, including clinicians). Content was further informed by published literature and our prior work., We used standard techniques to assess content validity, including systematic review by design experts, cognitive pretesting with 19 breast cancer survivors, and a pilot study including 67 women who participated in the baseline iCanCare study.

The primary dependent outcome variable was patient report of the decision to continue endocrine therapy beyond 5 years (yes vs no) at the time of the follow-up survey. Key covariates included respondent-assessed demographic and clinical factors, previously determined to be associated with endocrine therapy use, followed by key patient values (perceived benefits and barriers) related to breast cancer treatment decision making and involvement of the primary care physician (PCP) in the decision as a cue to action. Respondents were asked the importance of a series of 15 items related to their perceived benefits and barriers in making the decision to continue endocrine therapy (eg, oncologist recommendation, worry about recurrence, side effects) on a 5-point Likert scale from not at all to very important (dichotomized for analysis to quite or very important vs less important). Based on prior work documenting the importance of PCPs in cancer-related decision making,, respondents were asked, “How much has your primary care physician participated in the decision whether or not to take endocrine therapy for more than 5 years?” on a 5-point Likert scale from not at all to very much (dichotomized for analysis to any involvement vs none). We also assessed key baseline demographic (age, race, ethnicity, education level, income, marital status) and clinical and treatment factors (stage I-II, number of comorbidities, surgical procedure, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and prior endocrine therapy agent [any tamoxifen, aromatase inhibitors only, or other or unknown]). Stage and age at diagnosis were from the registries, and all other variables were from survey responses.

Statistical analyses

We provide descriptive statistics for all variables overall and by stage (I-II) to describe distribution and missingness, followed by a bivariate analysis of the decision to continue endocrine therapy for all covariates stratified by stage. Key covariates that were statistically significant in bivariate analysis (P < .01), as well as partner recommendation, which we previously found to be associated with treatment decisions, were included in a multivariable logistic regression, stratified by stage. The models were further adjusted for baseline demographics, clinical factors, and treatments noted above.

The multivariable analysis incorporated weights to account for differential probabilities of sample selection and potential bias because of nonresponse and to assure that sample distributions were representative of the target population (Supplementary Methods). To account for the potential impact of missing data, values for missing items were imputed using sequential regression multiple imputation with IVEware in SAS (Supplementary Methods, Table S1). Ten independently imputed complete datasets were analyzed separately. Exclusions and analytic sample size in each imputed dataset are shown in Table S2. Results were combined and inferential statistics calculated using PROC MIANALYZE in SAS. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Descriptive and bivariate analysis

Among women with estrogen receptor–positive and/or progesterone receptor–positive, stage I-II breast cancer (n = 831), 574 (69.1%) reported that they completed 5 years of endocrine therapy, 17 (2.0%) reported that they were still taking endocrine therapy (total = 591), 14.3% reported they never took endocrine therapy, 10.1% stopped before completing 5 years, and 4.5% did not answer this question (Figure S1).

Among the analytic cohort of women with estrogen receptor–positive and/or progesterone receptor–positive, stage I or II breast cancer who completed 5 years or were still taking endocrine therapy (and thus eligible to continue) and indicated that they had decided whether or not to continue endocrine therapy (n = 557), 261 (46.9%) decided to continue, and 296 (53.1%) decided not to continue (Table S3).

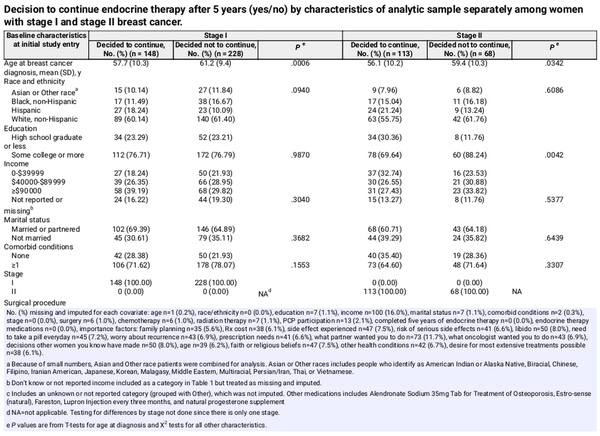

Those who decided to continue were younger (stage I: mean = 57.7 vs 61.2 years, P < .001; stage II: mean = 56.1 vs 59.4 years, P = .034). A greater proportion who decided to continue (vs not continue) received chemotherapy (stage I: 26.5% vs 13.3%, P = .001; stage II: 68.8% vs 41.2%, P < .001) and reported that their PCP was involved in the decision (stage I: 34.3% vs 11.3%, P < .001; stage II: 36.6% vs 10.3%, P < .001). A few stage-specific differences were found. Among women with stage I disease, a greater proportion of women who decided to continue (vs not continue) underwent bilateral mastectomy (stage I: 25.2% vs 12.0%, P = .005), and among women with stage II disease, a greater proportion of women who decided to continue (vs not continue) had a high school education or less (30.4% vs 11.8%, P = .004; Table 1; Table S3).

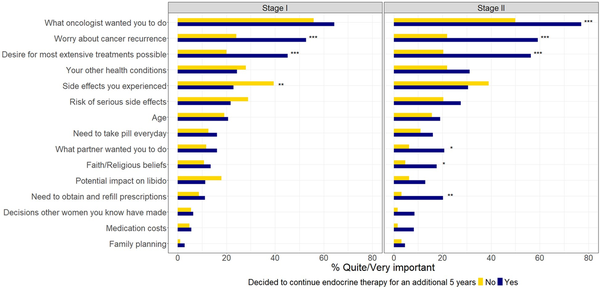

The bivariate comparison of the proportion of women who considered each key value quite or very important in decision making is shown in Figure 1 and Table S4, by decision to continue (yes vs no) and stage (I vs II). The most important factors were following the oncologist’s recommendation (overall 62.0% quite or very important), worry about recurrence (39.1%), and desire for the most extensive treatments possible (34.6%). Least important factors were family planning (2.5%), decisions other women made (5.8%), and medication cost (5.3%). The most and least important factors were similar in women with stage I and stage II breast cancer.

Figure 1

The importance of key patient values (benefits and barriers) in the decision whether to continue endocrine therapy, by stage. P values are from χ2 tests. ***P < .001; **P value of .001 to <.01, *P value of .01 to <.05.

Women who considered the following factors quite or very important were more likely to continue (P ≤ .001) among both stages I and II: worry about recurrence and desire for the most extensive treatments. Women with stage I breast cancer who reported that side effects they had experienced were quite or very important were less likely to continue (P = .001). Women with stage II breast cancer who considered the following factors quite or very important were more likely to continue following the oncologist’s recommendation (P < .001), doing what their partner wanted them to do (P = .012), prescription needs (P = .002), and faith or religious beliefs (P = .014; Figure 1).

Multivariable analysis

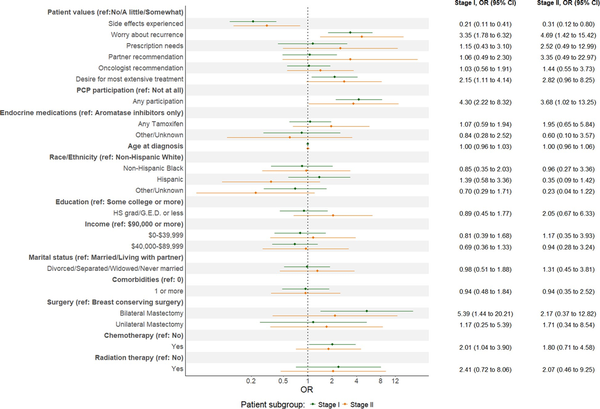

Figure 2 shows results of the multivariable logistic regression model stratified by stage using multiply imputed data. Conditional on other covariates, women with both stage I and II breast cancer who considered worry about recurrence and desire for the most extensive treatments possible quite or very important were more likely to continue (stage I: adjusted odds ratio [aOR] for worry = 3.35, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.78 to 6.32; aOR for extensive treatments = 2.15, 95% CI = 1.11 to 4.14; stage II: aOR for worry = 4.69, 95% CI = 1.42 to 15.42; aOR for extensive treatments = 2.82, 95% CI = 0.96 to 8.25). For both stages, side effects experienced were inversely associated with deciding to continue (stage I: aOR = 0.21, 95% CI = 0.11 to 0.41; stage II: aOR = 0.31, 95% CI = 0.12 to 0.80). PCP involvement was associated with deciding to continue (stage I: aOR = 4.30, 95% CI = 2.22 to 8.32; stage II: aOR = 3.68, 95% CI = 1.02 to 13.25). For stage I, receipt of bilateral mastectomy (vs breast conservation) and chemotherapy were statistically significantly associated with deciding to continue (bilateral mastectomy: aOR = 5.39, 95% CI = 1.44 to 20.21; chemotherapy: aOR = 2.01, 95% CI = 1.04 to 3.90). No other clinical or demographic variables were statistically significantly associated with deciding to continue in stage I or II (Figure 2). Results from regression models with demographic and clinical variables only are similar to those including patients’ values (Tables S5 and S6 for stage I and II, respectively). Results from models using complete case observed data are also similar to results using the imputed data (Table S7). A sensitivity analysis of stratifying patients by nodal status (N0 vs N1) yielded similar results as did the primary analysis by stage (Table S8).

Figure 2

Multivariable regression model results by breast cancer stage. Pooled estimates from weighted multivariable logistic regression model of decision to continue endocrine therapy using multiply imputed data adjusting for demographic, socioeconomic, clinical, treatment factors, and patient values, 10 imputed datasets. Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; HS = high school; OR = odds ratio; PCP = primary care physician; ref = referent.

Discussion

This is the first study of decisions about whether to extend endocrine therapy beyond 5 years among US women with breast cancer in community practice. It offers the first description of extended endocrine therapy uptake in a population-based cohort of women with stage I-II, estrogen receptor–positive and/or progesterone receptor–positive disease; approximately 40% with stage I and 60% with stage II decided to continue beyond 5 years. We found that the key values associated with deciding to continue were psychosocial and experiential. Notably, no demographic and few clinical or treatment variables were associated with this decision. The results suggest that decision making does not differ substantially by racial, ethnic, or other subgroup-specific factors, and they identify key motivating factors that should be addressed in shared decision making between oncologists and patients.

There is extensive published literature about toxicities of endocrine therapy, notably low-estrogen effects such as arthralgias, vaginal atrophy, and vasomotor symptoms, and about suboptimal adherence to 5 years of treatment. Registry and claims data from the United States, Canada, and Europe show declining adherence over the treatment course, from 70%-80% in the first year to 40%-60% by the fifth year., A Kaiser Permanente study showed less than 50% adherence for the recommended 5 years. Nonadherence has important consequences: it leads to higher rates of locoregional and distant recurrence and increased mortality. We found that 14% of women with stage I-II, estrogen receptor–positive and/or progesterone receptor–positive breast cancer never started endocrine therapy, and 11% stopped it early. The relatively high 5-year completion rate (70%) reported here may reflect greater tendency to treatment adherence among survey responders. We also observed a substantial uptake of extended treatment (nearly 40%) among patients with stage I disease, despite the lack of a definitive guideline recommendation for these patients to continue beyond 5 years. This finding aligns with results of the Young Women’s Breast Cancer Study, which reported that 60% of women chose extended endocrine therapy, and highlights the challenge of personalizing endocrine therapy duration—with potential risks of underutilization and overutilization.

Psychosocial factors, including perceived and experienced benefits and barriers and the cue to action provided by a PCP’s involvement, emerged as important drivers of the decision to extend endocrine therapy. Values that aligned with preferring more treatment, such as worry about cancer recurrence and desire for the most extensive treatment, were also associated with deciding to continue endocrine therapy. This is exemplified by the association between bilateral mastectomy receipt and deciding to continue endocrine therapy for stage I (but not stage II) patients—potentially identifying a low-risk, high-worry subgroup of patients who seek more extensive treatments than typically advised. Importantly, psychosocial factors and values may align with evidence-based treatment guidelines or against them (eg, preference for bilateral mastectomy in the absence of high contralateral breast cancer risk,). A related concern is that patients’ perceptions of low recurrence risk and information overload may contribute to endocrine therapy nonadherence., Thus, clinicians should be aware of how patients’ values and risk and benefit perceptions can drive treatment decision making in appropriate as well as inappropriate directions.

Another factor associated with deciding to continue endocrine therapy was PCP involvement in decision making. Earlier studies have documented the importance of an oncologist’s recommendation in patient decision making,, but less often highlighted the PCP’s role in choices about treatments directed by specialists. The current result may simply identify patients who are more engaged with the health-care system overall and thus prefer both PCP involvement and more extensive treatments; however, it also aligns with our prior finding that PCPs do play a role in patients’ cancer treatment decisions., These results should signal to oncologists the potential importance of PCPs in patients’ decision making about cancer treatments and inform future interventions to support patient decision making about endocrine therapy extension.

Previous US and European studies identified sociodemographic barriers to endocrine therapy adherence including cost and insufficient insurance coverage and demonstrated racial, ethnic, and income disparities in adherence., Another US study found lower adherence during vs before the COVID pandemic. Lower copayments, availability of generic vs brand-name aromatase inhibitors, and Medicare low-income subsidies have been associated with higher adherence. By contrast, we found no statistically significant difference by race, ethnicity, education, or income on multivariable analysis. This might reflect the recency of questionnaire administration (2021-2022), at a time when generic aromatase inhibitors and Medicare low-income subsidies were available and/or selection for patients who had already succeeded in completing 5 years of endocrine therapy. Additionally, patients in this study were diagnosed before CDK 4 and 6 inhibitors were offered as adjuvant therapy,, and further barriers of cost, insurance coverage, comorbidities, and toxicities may emerge in patients eligible for adjuvant CDK 4/6 inhibitor treatment.

This study has limitations. The original iCanCare study focused on women with favorable-prognosis breast cancer and excluded those with stage III disease. Treatment completion was measured by self-report only. Given the sample’s median diagnosis age of 61 years, premenopausal women eligible for ovarian function suppression were underrepresented. As noted above, the diagnosis period of 2014-2015 predates use of adjuvant CDK 4 and 6 inhibitors, so results do not reflect this more arduous treatment experience. Use of emerging assays for benefit from endocrine therapy extension, such as the HOXB13/IL7BR ratio, was not ascertained. Women were diagnosed in 2 states only (Georgia and California) so may not represent the whole US population. The follow-up survey response rate was 60%, and experiences of nonresponders may have differed from those of responders; however, we weighted multivariable analyses for nonresponse to mitigate this. The study’s limitations are balanced by notable strengths including a large, diverse, contemporary population-based sample, surveyed in 2021-2022 about their treatment decision making 6-7 years into breast cancer survivorship. Additionally, nearly all patients were contacted near the time of decisions about continuing endocrine therapy, which likely enhanced their recall of treatment experiences and circumstances of decision making.

These results have implications for patient care. Notwithstanding evidence that endocrine therapy adherence is suboptimal,,,,,, we found that around half (approximately 40% stage I, 60% stage II) of women who completed 5 years chose to continue treatment, and this decision was most associated with perceived risk and benefit, preference for extensive treatment, and the cue to action signified by PCP involvement. With some prior studies showing less than 50% completion of 5 years of treatment, our finding that more than 50% of higher-risk (stage II) patients chose extended therapy is encouraging—as is the fact that pertinent clinical factors, rather than nonpertinent demographic factors such as race, ethnicity or education, drove patients’ treatment decision making. These results should prompt oncologists to discuss extended endocrine therapy with all clinically indicated patients and to address the influential psychosocial and experiential factors that inform treatment decision making. Finally, primary care coordination with oncologists may help optimize treatment decision making as patients enter the survivorship period.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the work of our project staff from the Georgia Cancer Registry, the University of Southern California, and the University of Michigan. We acknowledge with gratitude the patients with a history of breast cancer who responded to our survey.

The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors. The State of California, Department of Public Health, the NCI, and the CDC and their contractors and subcontractors had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

This work was presented in part at the 2023 ASCO Quality Care Symposium in Boston, MA, USA.

References

- 1. Caswell-Jin JL, Sun LP, Munoz D, et al Analysis of breast cancer mortality in the US-1975 to 2019. JAMA. 2024;331:233–241.

- 2. Kurian AW, Bondarenko I, Jagsi R, et al Recent trends in chemotherapy use and oncologists’ treatment recommendations for early-stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:493–500.

- 3. Sparano JA, Gray RJ, Makower DF, et al Adjuvant chemotherapy guided by a 21-gene expression assay in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:111–121.

- 4. Kalinsky K, Barlow WE, Gralow JR, et al 21-Gene assay to inform chemotherapy benefit in node-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2336–2347.

- 5. Francis PA, Regan MM, Fleming GF, et al; International Breast Cancer Study Group. Adjuvant ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:436–446.

- 6. Pagani O, Regan MM, Walley BA, et al; International Breast Cancer Study Group. Adjuvant exemestane with ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:107–118.

- 7. Johnston SRD, Harbeck N, Hegg R, et al; monarchE Committee Members and Investigators. Abemaciclib Combined With Endocrine Therapy for the Adjuvant Treatment of HR+, HER2-, Node-Positive, High-Risk, Early Breast Cancer (monarchE). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:3987–3998.

- 8. Slamon D, Lipatov O, Nowecki Z, et al Ribociclib plus endocrine therapy in early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:1080–1091.

- 9. Freedman RA, Caswell-Jin JL, Hassett M, et al; Optimal Adjuvant Chemotherapy and Targeted Therapy for Early Breast Cancer Guideline Expert Panel. Optimal adjuvant chemotherapy and targeted therapy for early breast cancer-cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 inhibitors: ASCO guideline rapid recommendation update. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:2233–2235.

- 10. Del Mastro L, Mansutti M, Bisagni G, et al; Gruppo Italiano Mammella Investigators Extended therapy with letrozole as adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal patients with early-stage breast cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:1458–1467.

- 11. Gnant M, Fitzal F, Rinnerthaler G, et al; Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group. Duration of adjuvant aromatase-inhibitor therapy in postmenopausal breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:395–405.

- 12. Burstein HJ, Lacchetti C, Anderson H, et al Adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline focused update. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:423–438.

- 13. Hamilton AS, Hofer TP, Hawley ST, et al Latinas and breast cancer outcomes: Population-based sampling, ethnic identity, and acculturation assessment. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2022–2029.

- 14. Gradishar WJ, Moran MS, Abraham J, et al NCCN Guidelines(R) insights: breast cancer. Version 4.2021. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19:484–493.

- 15. Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the Health Belief Model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15:175–183.

- 16. Nekhlyudov L, Mollica MA, Jacobsen PB, et al Developing a quality of cancer survivorship care framework: implications for clinical care, research, and policy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111:1120–1130.

- 17. Hawley ST, Griffith KA, Hamilton AS, et al The association between patient attitudes and values and the strength of consideration for contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in a population-based sample of breast cancer patients. Cancer. 2017;123:4547–4555.

- 18. Radhakrishnan A, Reyes-Gastelum D, Gay B, et al Primary care provider involvement in thyroid cancer survivorship care. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:e3300-6–e3306.

- 19. Simes RJ, Coates AS. Patient preferences for adjuvant chemotherapy of early breast cancer: How much benefit is needed? J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2001;2001:146–152.

- 20. Wallner LP, Abrahamse P, Uppal JK, et al Involvement of primary care physicians in the decision making and care of patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3969–3975.

- 21. Wallner LP, Li Y, McLeod MC, et al Primary care provider-reported involvement in breast cancer treatment decisions. Cancer. 2019;125:1815–1822.

- 22. Veenstra CM, Hawley ST, McLeod MC, et al Partnered status and receipt of guideline-concordant adjuvant chemotherapy among patients with colon cancer. Cancer. 2019;125:4232–4240.

- 23. Veenstra CM, Wallner LP, Abrahamse PH, et al Understanding the engagement of key decision support persons in patient decision making around breast cancer treatment. Cancer. 2019;125:1709–1716.

- 24. Wallner LP, Li Y, McLeod MC, et al Decision-support networks of women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Cancer. 2017;123:3895–3903.

- 25. Ragunathan TB, Solenberger PA, Peter W. Multiple Imputation in Practice with Examples Using IVEware. 1st ed. Chapman & Hall; 2018:264.

- 26. Aiello Bowles EJ, Boudreau DM, Chubak J, et al Patient-reported discontinuation of endocrine therapy and related adverse effects among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:e149–e157.

- 27. Henry NL, Azzouz F, Desta Z, et al Predictors of aromatase inhibitor discontinuation as a result of treatment-emergent symptoms in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:936–942.

- 28. Nabieva N, Kellner S, Fehm T, et al Influence of patient and tumor characteristics on early therapy persistence with letrozole in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer: results of the prospective Evaluate-TM study with 3941 patients. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:186–192.

- 29. Blanchette PS, Lam M, Richard L, et al Factors associated with endocrine therapy adherence among post-menopausal women treated for early-stage breast cancer in Ontario, Canada. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;179:217–227.

- 30. Hershman DL, Neugut AI, Moseley A, et al Patient-reported outcomes and long-term nonadherence to aromatase inhibitors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113:989–996.

- 31. van den Biggelaar Y, Kuiper JG, van der Sangen MJC, et al 5-year adherence to adjuvant endocrine treatment in Dutch women with early stage breast cancer: a population-based database study (2006-2016). Breast Dis. 2023;42:331–339.

- 32. Partridge AH, LaFountain A, Mayer E, et al Adherence to initial adjuvant anastrozole therapy among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:556–562.

- 33. Wulaningsih W, Garmo H, Ahlgren J, et al Determinants of non-adherence to adjuvant endocrine treatment in women with breast cancer: the role of comorbidity. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;172:167–177.

- 34. Reeder-Hayes KE, Mayer SE, Lund JL. Adherence to endocrine therapy including ovarian suppression: a large observational cohort study of US women with early breast cancer. Cancer. 2021;127:1220–1227.

- 35. Zhao H, Lei X, Niu J, et al Prescription patterns, initiation, and 5-year adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy among commercially insured patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol Oncol Pract. 2021;17:e794–e808.

- 36. Gremke N, Griewing S, Chaudhari S, et al Persistence with tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors in Germany: a retrospective cohort study with 284,383 patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149:4555–4562.

- 37. Schmidt JA, Woolpert KM, Hjorth CF, et al Social characteristics and adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in premenopausal women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:3300–3307.

- 38. Ransohoff JD, Lewinsohn RM, Dickerson J, et al Endocrine therapy interruption, resumption, and outcomes associated with pregnancy after breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2025. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2024.6868

- 39. Hershman DL, Kushi LH, Shao T, et al Early discontinuation and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in a cohort of 8,769 early-stage breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4120–4128.

- 40. Hershman DL, Shao T, Kushi LH, et al Early discontinuation and non-adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy are associated with increased mortality in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126:529–537.

- 41. Chirgwin JH, Giobbie-Hurder A, Coates AS, et al Treatment adherence and its impact on disease-free survival in the breast international group 1-98 trial of tamoxifen and letrozole, alone and in sequence. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2452–2459.

- 42. Matar R, Sevilimedu V, Gemignani ML, et al Impact of endocrine therapy adherence on outcomes in elderly women with early-stage breast cancer undergoing lumpectomy without radiotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29:4753–4760.

- 43. Park C, Heo JH, Mehta S, et al Adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy and survival among older women with early-stage hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Clin Drug Investig. 2023;43:167–176.

- 44. Sella T, Zheng Y, Rosenberg SM, et al Extended adjuvant endocrine therapy in a longitudinal cohort of young breast cancer survivors. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2023;9:31.

- 45. Hawley ST, Jagsi R, Morrow M, et al Social and clinical determinants of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:582–589.

- 46. Jagsi R, Hawley ST, Griffith KA, et al Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy decisions in a population-based sample of patients with early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:274–282.

- 47. Bellavance E, Peppercorn J, Kronsberg S, et al Surgeons’ perspectives of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:2779–2787.

- 48. Brier MJ, Chambless DL, Gross R, et al Perceived barriers to treatment predict adherence to aromatase inhibitors among breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2017;123:169–176.

- 49. Eraslan P, Tufan G. Cancer information overload may be a crucial determinant of adjuvant aromatase inhibitor adherence. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26:7053–7062.

- 50. Engelhardt EG, Smets EMA, Sorial I, et al Is there a relationship between shared decision making and breast cancer patients’ trust in their medical oncologists? Med Decis Making. 2020;40:52–61.

- 51. Puts MT, Sattar S, McWatters K, et al Chemotherapy treatment decision-making experiences of older adults with cancer, their family members, oncologists and family physicians: a mixed methods study. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:879–886.

- 52. Radhakrishnan A, Li Y, Furgal AKC, et al Provider involvement in care during initial cancer treatment and patient preferences for provider roles after initial treatment. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15:e328–e337.

- 53. Farias AJ, Du XL. Association between out-of-pocket costs, race/ethnicity, and adjuvant endocrine therapy adherence among Medicare patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:86–95.

- 54. Neuner JM, Kamaraju S, Charlson JA, et al The introduction of generic aromatase inhibitors and treatment adherence among Medicare D enrollees. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:djv130.

- 55. Wheeler SB, Spencer J, Pinheiro LC, et al Endocrine therapy nonadherence and discontinuation in black and white women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111:498–508.

- 56. McGuinness S, Hughes L, Moss-Morris R, et al Adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy among White British and ethnic minority breast cancer survivors in the United Kingdom. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2022;31:e13722.

- 57. Rahimi S, Ononogbu O, Mohan A, et al Adherence to oral endocrine therapy in racial/ethnic minority patients with low socioeconomic status before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Clin Pharm. 2023;45:1396–1404.

- 58. Neugut AI, Subar M, Wilde ET, et al Association between prescription co-payment amount and compliance with adjuvant hormonal therapy in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2534–2542.

- 59. Hershman DL, Tsui J, Meyer J, et al The change from brand-name to generic aromatase inhibitors and hormone therapy adherence for early-stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju319.

- 60. Ma S, Shepard DS, Ritter GA, et al The impact of the introduction of generic aromatase inhibitors on adherence to hormonal therapy over the full course of 5-year treatment for breast cancer. Cancer. 2020;126:3417–3425.

- 61. Qin X, Huckfeldt P, Abraham J, et al Hormonal therapy drug switching, out-of-pocket costs, and adherence among older women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114:1029–1035.

- 62. Noordhoek I, Treuner K, Putter H, et al Breast cancer index predicts extended endocrine benefit to individualize selection of patients with HR(+) early-stage breast cancer for 10 years of endocrine therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:311–319.