Organized activities are out-of-school settings supervised by adults with regular meetings that include a group of youth working toward a common goal (e.g., sports, arts, school clubs, religious activities, community-based programs; ; ). These activities provide opportunities for Latinx adolescents to develop skills, knowledge, and resources that help them thrive (; ; ). Organized activities can be especially beneficial for Latinx adolescents because they often face high rates of poverty and experience racism and discrimination that contribute to disparities in their educational and health outcomes compared to peers from other racial/ethnic groups (; ; ).

To promote Latinx adolescents’ participation in organized activities, it is important to understand the connections between organized activities and families. Information on the potential benefits and challenges for families can help organized activities develop culturally responsive activities that promote adolescents’ enrollment and consistent participation and support family engagement (; ; ). However, the organized activity literature has largely focused on the influence organized activities have had on adolescents only and has rarely examined how organized activities are beneficial and challenging for families. This study aims to examine the perceptions of Mexican-origin parents about the benefits and challenges of adolescents’ participation in organized activities for their family.

Adolescents’ Organized Activity Participation and Their Families

Extending cultural () and ecological theories (), cultural-ecological theories provide insight into how adolescents’ participation in organized activities might influence families (; ; ). Cultural-ecological theories suggest that the practices and social interactions that a developing individual engages in within a developmental context shape the individual’s practices and social interactions in other developmental contexts. Thus, according to cultural-ecological theories, the activities and social interactions that adolescents are exposed to through organized activities will shape family practices, interactions, and resources. For example, participation in organized activities could influence the time families have to spend together (e.g., family dinner time) and adolescents’ relationships with family members. Overall, cultural-ecological theories (; ; ) highlight the value of considering the influence of organized activities on adolescents’ activities and social interactions in their family context.

The few studies that have considered how organized activities may shape families suggest activities can benefit families by (a) providing adolescents a safe place, (b) promoting adolescent skill development, and (c) supporting positive family interactions. First, organized activities can provide a safe environment during the after-school hours that gives parents peace of mind (; ). For example, parents of adolescents participating in a variety of activities, including sports, arts, and religious activities, have reported appreciating organized activities for providing supervision that protects their children from dangerous situations (e.g., getting exposed to violence) and risky behaviors (e.g., doing drugs; ; ). Second, activities help promote skills that can influence adolescents’ behavior at home, such as responsibility and socioemotional skills (e.g., emotional regulation; ; ; ). Some studies suggest that the sense of responsibility that adolescents develop in a range of activities (e.g., art activities, school clubs, and religious activities) influences how they behave with family (; ). Third, adolescents’ activity participation may also contribute to positive interactions among family members, such as having something for parents and adolescents to share, talk about, and experience together (e.g., attending sport games as a family; ; ). In sum, the current literature suggests that adolescents’ activity participation can benefit individual family members as well as family dynamics and relationships.

There is also empirical evidence from a few studies suggesting families can experience the following challenges regarding adolescents’ activity participation: (a) constraints on family resources, (b) family conflict, and (c) exposure to physical harm. A major challenge for families is the investment of family resources, including money, transportation, and time, that come with adolescents’ organized activities (; ). For example, the time commitment needed for participating in a variety of organized activities can interfere with other family activities (; ). Sport activities particularly require a significant time commitment for families in terms of attending practices and games that disrupt parents’ work obligations, housework, and family time together (). Additionally, adolescents’ participation in organized activities can strain family relationships. For example, reported that conflict ensued between parents and their adolescents when parents disapproved of their adolescents’ involvement in community-based programs that conflicted with their family values. Lastly, parents of adolescents participating in sports activities have expressed concerns about their adolescents being exposed to physical harm through injuries (). In conclusion, there is some indication that adolescents’ organized activity participation can present challenges to family resources, routines, and relationships.

Some studies suggest that the benefits and challenges that families experience may vary based on the type of organized activity. Particularly, the unique characteristics of sport activities may contribute to differences in the benefits and challenges that families experience, compared to other activities, such as art activities, religious activities, school clubs, and community-based organizations (, ; ). For example, sport activities often offer weekly (or multiple) opportunities for family members to spend time together through attending sports games and matches as a family, whereas other activities might offer these opportunities less frequently (e.g., recitals for music or dance activities) (). Moreover, a study conducted by found that parents especially valued the socioemotional skills that their adolescents gained from participating in individual and team sports compared to other activities, like art activities and community-based activities. On the other hand, the requirement to attend practices and games multiple times a week may become overwhelming for family members as it can interfere with other activities like parents’ work (). Participating in sports can also be particularly costly for families as some sports require families to pay for equipment, uniforms, and travel costs (). All in all, empirical evidence suggests that it is valuable to consider the type of activity when examining the family benefits and challenges of adolescents’ participation in organized activities.

In sum, the existing literature provides insight into some of the potential benefits and challenges that families may experience, including how these benefits and challenges may differ across types of activities. However, the existing research is limited. For instance, the literature has largely not considered how culture and ethnicity might influence these processes as theorized in cultural-ecological theories (; ) nor considered many of these processes for Latinx families. Thus, it is important to consider how the cultural values and practices of Mexican-origin families may shape the benefits and challenges they perceive from activities.

The Role of Enculturation in the Experiences of Latinx Families With Organized Activities

Aligned with the emphasis on culture outlined in cultural-ecological theories (; ), developmental scholars have argued for the importance of considering the role of culture in organized activities. proposed that race and ethnicity function as social categories and cultural contexts that influence youth’s interactions in organized activities. Moreover, adolescents bring cultural expectations from their family ethnic socialization that shapes their experiences within activities and the benefits they derive from participating (). agree with these tenets and argued that organized activities should strive to be responsive to youth’s and families’ culture to maximize their positive impacts. Through their framework, proposed a series of culturally responsive practices for organized activities that included strengthening family-activity connections, centering youth and family voice, and incorporating family practices, knowledge, and concerns into activity programing.

Although and underscore the importance of racial and ethnic culture, they do not address the specific cultural processes of Mexican ethnic culture. The model of Latino youth development provides guidance on the specific cultural processes that may shape the experiences of Mexican-origin families with organized activities (). The model posits that an important cultural mechanism to consider in the development of Latinx youth is enculturation, which entails remaining connected to cultural values and practices that are prominent in the Latinx culture, such as familism (i.e., valuing family unity and connectedness) and respeto (i.e., respect for parents and elders). The model also highlights that the Latinx community is not a monolithic group and that it is valuable to consider the cultural diversity within the Latinx community. Essentially, the diverse cultural experiences of Latinx adolescents and their families can distinctly shape the adolescents’ development. Overall, based on the model of Latino youth development (), Mexican-origin parents may perceive distinct family benefits and challenges from their adolescents’ participation in organized activities based on their level of enculturation.

Previous research suggests that participating in organized activities can support and promote the enculturation of Latinx families, including those of Mexican-origin (; ; ; ). Specifically, organized activities can promote Mexican-origin adolescents’ connection to their ethnic culture by creating activities that reinforce Mexican ethnic cultural values and cultural practices (). For example, there is empirical evidence that some Mexican-origin parents particularly value religious activities that teach their adolescents to respect their elders, which aligns with the Mexican ethnic cultural value of respeto (; ; ). Moreover, other qualitative studies conducted with community-based programs and after-school programs have found that Latinx youth appreciate activity staff for allowing and encouraging them to celebrate cultural holidays (e.g., Dia de los Muertos) and practice Spanish (; ; ). Essentially, there is empirical evidence suggesting that Mexican-origin families who are more enculturated to Mexican ethnic culture may perceive organized activities that support traditional Mexican cultural values and practices as more beneficial for their family than families who are less enculturated.

Adolescents’ participation in organized activities also has the potential to conflict with the enculturation of Mexican-origin families (). Organized activities can expose adolescents to experiences of discrimination that can strain their positive connection to their ethnic cultural identity (; ). A study conducted with after-school programs found that some programs discouraged Latinx adolescents from speaking Spanish in their programs (). Other qualitative studies found that Latinx parents have concerns about organized activities conflicting with their ethnic cultural values (; ). In a study conducted by , Mexican-origin parents expressed concerns about their adolescents’ participation in organized activities conflicting with the Mexican cultural value of familism by interfering with the time that the family can spend together. Cultural misalignments between families and organized activities may contribute to growing differences in the cultural orientations of parents and their adolescents (i.e., acculturation gaps), which can lead to family conflict and youth maladjustment (; ). All in all, Mexican-origin families who are more enculturated, compared to families who are less enculturated, may perceive organized activities as more challenging if they perceive cultural misalignments with their Mexican ethnic culture.

Overall, previous literature suggests that the experiences Mexican-origin families have with organized activities are shaped by their culture, including their level of enculturation to Mexican ethnic culture. However, the literature has only tangentially addressed how parents’ enculturation may inform the different benefits and challenges that Mexican-origin families experience through their adolescents’ activities. Given the centrality of culture in the daily lives of Mexican-origin families in the U.S. (; ), it is valuable to further explore the role of culture in their experiences. Insight into this topic can inform activities in developing programming and services that are culturally responsive for Mexican-origin families ().

Current Study

Based on the gaps in the literature, this study proposes to leverage the perspectives of Mexican-origin parents to obtain insight on how they think their adolescents’ participation in organized activities may benefit or challenge their family. It is particularly important to understand more about this topic during adolescence, given that families and organized activities may play an especially consequential role as adolescents go through the physiological, socioemotional, and cognitive changes associated with this stage (). Through a mixed-methods approach, we captured Mexican-origin parents’ perspectives on the benefits and challenges of their adolescent participating in organized activities for their family and examined whether parents’ perceptions varied depending on their level of enculturation. Although it was not a central goal of the study, we also examined differences based on activity type following preliminary literature that suggests the benefits and challenges might vary by activity type. Insights from this study are valuable for researchers and practitioners who work with organized activities that serve Mexican-origin adolescents and their families and seek to better support this community.

Method

Research Design and Participants

Participants were part of a study that focused on Mexican-origin 7th grade adolescents’ and their parents’ perceptions and experiences with organized activities (; ). A total of 34 pairs of adolescents and parents were recruited into this study and interviewed multiple times throughout the 2009–2010 school year. Our study focused on the interviews that were conducted with the parents. An institutional review board approved the protocols and procedures that we followed for this study.

Mexican-origin adolescents and their parents were recruited through purposive sampling from three public middle schools in a large southwestern metropolitan city in the United States. The schools were purposely selected to help capture the variability among Latinx families in the area in terms of social class, ethnic compositions of the schools the adolescents attended, and the family immigration history. School A served predominantly White middle-class families (60% White and 21% free-reduced lunch), whereas Schools B and C served predominantly Latinx families from low-income backgrounds (88% and 91% Latinx and 78% and 93% free and reduced lunch). Most students from School B came from families who were in the U.S. for multiple generations, and most students in School C came from recently immigrated families. The sample was stratified based on the school (i.e., about 30% from each school), adolescents’ organized activity participation during the fall (i.e., about 50% participated in an activity and 50% did not), and gender (i.e., about 50% were girls).

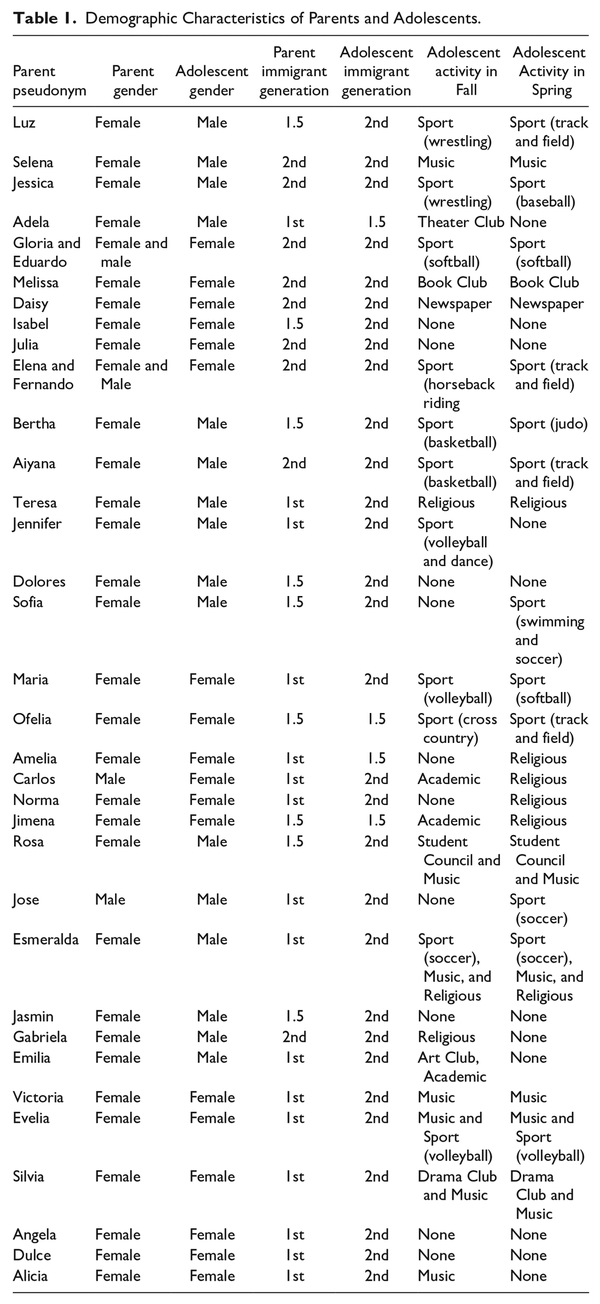

Of the 34 parents, 16 were 1st generation immigrants (n = 16), and the remaining parents were either 1.5 generation (i.e., born outside the U.S. but childhood was spent in the U.S.; n = 9) or 2nd generation (i.e., born and raised in the U.S.; n = 9). On average, parents were 39.45 years old. Most parents that completed the interviews were mothers (94%). For two of the families, both the mother and father participated in the interviews, and two fathers completed the interviews by themselves. The median yearly family income was about $20,000 to $29,999, and 31% of parents had some college experience. Most parents were married (70%), and the rest were in single-parent households. Of the adolescents, 53% were girls and were, on average, 12.45 years old. Most adolescents were born and raised in the U.S. (88%), and the rest were 1.5 generation immigrants. Table 1 includes details about parent and adolescent demographics and activity participation for each family.

Adolescents in our study experienced diverse patterns of participation throughout the 2009–2010 school year. First, more than half of the adolescents were participating in an organized activity (n = 24) at the beginning of the study during the fall of 2009. Of those adolescents who were not initially participating in an activity, four eventually participated in an organized activity during the spring of 2010. In total, 6 (18%) adolescents did not participate in an organized activity during the fall and/or spring of the 2009–2010 school year. Although six adolescents did not participate in organized activities during the school year, parents were asked about their perceptions on organized activities and their adolescents’ experiences with activities (e.g., conversations about an activity an adolescent wanted to join). Parents whose adolescents did not participate in an activity were included to understand how the benefits and challenges that families experience may shape family decisions to not participate in activities. Among adolescents who participated in activities, sports was the most commonly mentioned activity (46%). Adolescents also mentioned participating in art activities (25%), religious activities (25%), and extracurricular clubs (11%). Of participating adolescents, 23 reported participating in at least one activity that took place in their middle school, whereas 12 adolescents reported participating in at least one activity that took place in the community (e.g., community-based organization, church).

Interview Procedures

A series of two semi-structured qualitative interviews was were conducted with the 34 parents, once in the fall of 2009 and then again in the spring of 2010. Interviews generally lasted between 45 and 90 minutes. Interviewers were trained on research ethics and effective interviewing techniques. During data collection, the team held weekly debriefing sessions to discuss any issues that arose. Half of the parents (n = 17) were interviewed in English, with the remainder interviewed in Spanish by native Spanish speakers from the local community. The audiotaped interviews were transcribed verbatim. A second transcriber revised the initial transcription through a secondary check. For interviews in Spanish, a six-step process was followed that included secondary checks of the transcription and of the translation to ensure accuracy of the translation and cultural meaning (). Pseudonyms were used in all the interview data.

The semi-structured interview script included open-ended questions that were informed by previous literature (; ; ), but also allowed for probing to obtain in-depth responses from parents. The interview started with defining organized activities as activities that have an adult leader and meet at regularly scheduled times. Parents were asked about their general thoughts concerning organized activities, including whether they thought organized activities were helpful or challenging for parents and families. If their adolescent was participating in an organized activity, parents were also asked questions specific about the activity, such as what they thought their adolescent was learning or gaining at the activity, whether the adolescent was facing any challenges, and whether the adolescent’s participation in the activity was helpful or challenging to the parent/family. Although entire interview transcripts were analyzed, the majority of the coding was drawn from the following questions: Do you think kids’ organized activities are helpful for parents or families?, Would you say that [your child]’s participation (was/is) helpful or beneficial to you? If yes, how was it helpful?, What (were/are) some of the challenges in having [your child] involved in [activity]?, and Did you have to make adjustments to your family routine to accommodate [your child’s] participation?

Parents’ level of enculturation was measured using the enculturation scale from the Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans (ARMSA-II; ; ; ). The enculturation scale included six items, such as “I enjoy reading in Spanish” and “I enjoy watching movies in Spanish” (alpha = .96; 1 = not at all, 3 = moderately, 5 = extremely often or almost always). The items were averaged to create an overall score that was used to determine whether parents had high or low levels of enculturation.

Coding and Analysis

We conducted a mixed-method analysis that integrated qualitative and quantitative data analysis in a sequential manner (; ). Particularly, we started with a qualitative analysis of the parent interviews and followed with a quantitative analysis that extended the qualitative analysis. First, we conducted a thematic analysis of the parent interviews to understand parents’ perceptions of the benefits and challenges for the family (). Then, we used the themes of family benefits and challenges we found from the thematic analysis to conduct a cross-case analysis that compared the frequency of the themes across two groups based on parents’ enculturation (). We used this mixed-methods approach to strengthen our understanding of parents’ perceptions of the benefits and challenges of participating in organized activities for their families.

For the thematic analysis, the first author coded the interviews through multiple iterative stages using a coding software called NVivo. Both deductive and inductive approaches were applied, such that the coding was informed by prior literature on families and organized activities as well as new information that emerged from the data (; ). Thus, although the existing literature was consulted throughout the analysis process, the authors remained open to new insights from the data. Detailed memos were written that documented the first author’s reflective thoughts about the coding process (; ).

During the first stage of coding, a preliminary coding framework was developed based on coding the interviews of about one-third of the sample (i.e., 12 parents). The codes were determined using both in-vivo (i.e., verbatim words or phrases from transcripts) and descriptive (i.e., words or phrases that summarize a topic) techniques (). The initial codes were shared with the larger research team and any discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached (). Additionally, the existing literature and the memos written during the coding process were consulted. Overall, the first author used discussions with the research team, the existing literature, and the written memos to refine the codes in the preliminary coding framework.

In the second stage of coding, the preliminary coding framework was applied to code all parent interviews. The coding framework was redefined based on coding the remaining data, reviewing written memos of the coding process, previous literature, and meetings with the research team. The purpose of this stage was to create a stronger coding framework that captured the unique perspectives of all parents in the study about how activities may benefit and challenge families. In the third and final stage of coding, broader themes were created by continuously consulting the coding framework, interview data, previous literature, and written memos. The themes were based on the common patterns we found across the categories of family benefits and challenges from the second stage of coding. For example, the separate codes where parents talked about organized activities, preventing problem behavior and providing safety and adult supervision, reflected a common pattern of parents perceiving organized activities as a safe space for adolescents, and thus were combined into a theme called protection. Once we determined the themes, we analyzed the instances across themes in which parents mentioned the activity type in their responses to determine whether activity type differentially shaped parents’ perceptions of the benefits and challenges of organized activities.

Lastly, to determine whether and how parents’ perceptions of the benefits and challenges varied based on parents’ level of enculturation, a cross-case analysis was conducted (). Parents’ responses to the enculturation scale of the ARMSA-II were used to categorize them into two groups: High enculturation (n = 15) included parents whose average response was above the mean (i.e., 3.71), and low enculturation (n = 12) included parents whose average response was below the mean (). Seven parents from the initial sample of 34 parents were not included in this part of the analysis because they did not report their level of enculturation. The cross-case analysis consisted of analyzing whether the themes of family benefits and challenges were present in each group, determining the frequency of the themes in each group, and analyzing whether the themes manifested differently across the two groups.

Positionality

The first author acknowledges that although they share a common identity with the target population of this study, as they identify as Mexican American, they are not part of the local community where the data were originally collected from. The first author also recognizes that the value they place on the potential of families and organized activities to support the positive development of Latinx adolescents informs their research work. The second author, who is the principal investigator of the original study, is a White woman raised in California, whose family has been in the U.S. for more than three generations. She has previously conducted research on adolescents’ organized activity participation and the role of family involvement, including with Latinx populations. To account for potential biases related to the experience of the Mexican-origin families in the study or the role of organized activities in the development of youth, we consulted with a larger research team throughout the data analysis process. Specifically, we discussed any potential biases and assumptions that may influence the analysis process with a research team that was composed of other graduate students and post-doctoral scholars from diverse ethnic backgrounds.

Results

Benefits and Challenges of Organized Activities for Mexican-Origin Families

This section addresses what parents in this study perceived as the family benefits and challenges. Below, we use parent interview excerpts to describe and distinguish between the family benefits and challenges.

Benefits for Families

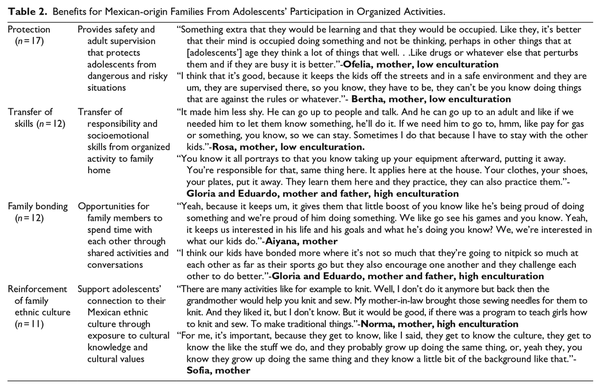

The family benefits included protection, family bonding, transfer of skills, and reinforcement of family ethnic culture (Table 2).

Protection

Parents mentioned that activities protected adolescents from risky and dangerous situations by providing safety, supervision, and preventing problem behavior (n = 17). This theme was largely determined based on deductive insights from previous literature (; ; ). In terms of safety, parents said they appreciated knowing where their adolescent was and what they were doing when they were at their activity, as opposed to the adolescent being free to roam “the streets.” Relatedly, parents suggested that the adult supervision that activities provided was key, as parents thought an adolescent who was left unsupervised after school was more likely to be exposed to dangerous situations. Lastly, parents appreciated that organized activities prevented their adolescents from engaging in risky behaviors, such as taking drugs and being involved in gangs. For example, Teresa, a mother in the study, mentioned the following about the benefit of her son participating in an organized activity:

Well, I think they are great. Right, they are groups that keep the young, the adolescents, busy, right. Out of other things that they shouldn’t do. Out of gangs or of the groups, not gangs, they don’t have to be gangs, but little groups of boys out there. And for his age, that is probably, maybe they don’t do things with bad intent, but regardless, they are hurting themselves.

Teresa appreciated that activities kept her son occupied and prevented him from engaging in risky behaviors, like being involved in a gang. Overall, Mexican-origin parents in this study perceived that the protection activities provided was helpful for families because it brought relief to parents that their youth were safe when they were not able to directly supervise them.

Transfer of Skills

Parents highlighted that another family benefit was adolescents transferring responsibility and socioemotional skills from the activity to the family (n = 12). This theme was based on deductive insight from previous literature about the transfer of responsibility (; ) and inductive insights from parents about the transfer of socioemotional skills. When talking about adolescents’ responsibility, parents thought that adolescents’ sense of responsibility they gained at their activity led to an increased willingness and ability to take on more responsibility at home. For example, one of the mothers, Elena, mentioned that her daughter’s participation in sports motivated her to be “more committed to her responsibilities,” like cleaning her room. Parents also talked about the transfer of socioemotional skills (e.g., emotional regulation), which has been understudied. Silvia, a mother, discussed her daughter learning to control her emotions through her music activity:

Well, I think that, like how to relate more with other people and also for her how to control her emotions because sometimes when she gets mad, she locks herself in her room and starts playing. And I say that it calms her, it helps her calm down.

Silvia’s daughter played her musical instrument to control her emotions when she was upset at home. Parents in the study also mentioned that the socioemotional skills adolescents learned at activities contributed to more cordial interactions with family members as adolescents were “calmer” and “easier to communicate with.” Mexican-origin parents in this study felt the sense of responsibility and socioemotional skills that adolescents gained from activities were assets for families that contributed to positive family functioning and relationships.

Family Bonding

Parents mentioned that adolescents’ participation created opportunities for family members to spend time together and bond as a family, including shared family activities and conversations (n = 12). Given the limited literature on this topic, this theme more heavily draws on inductive analysis. For example, parents in the study talked about the benefit of spending time together as a family during activity events. As parents mentioned, this benefit was particularly possible in sport activities as families could regularly attend sport events, like games, matches, and track meets, to support their participating adolescent. One of the mothers in the study, Ofelia, mentioned the following about their family attending her daughter’s track race:

When she’s going to race, we all go and then once she finishes, we go get something and we all come back happy. Talking about who we saw or we saw this kid or the kids that took first place and all of that.

As Ofelia describes, her daughter’s track meets provided an opportunity for their family to share a warm and joyful experience. Parents like Ofelia thought adolescents’ activities were beneficial because they positively contributed to the family functioning as a whole. Additionally, parents talked about activities providing opportunities for parent-adolescent conversations. These conversations allowed parents to communicate more with their adolescents and learn more about their adolescents’ interests and activities. Overall, Mexican-origin parents of this study felt that the shared family activities and conversations were benefits of organized activities and reflect their value of strong family connections and relationships (i.e., familism).

Reinforcement of Family Ethnic Culture

A fourth theme of family benefits was the reinforcement of family ethnic culture (n = 11). This theme was partially based on deductive insights from previous literature on Mexican ethnic culture and inductive insights from parents’ unique cultural perspectives (; ). Parents appreciated when activities supported adolescents’ connection to their Mexican ethnic culture through exposure to cultural knowledge and values. For example, Silvia appreciated that her daughter’s band activity taught Spanish songs because “[her daughter] also needs to learn where her roots come from, her parents’ culture.” For adolescents who were not involved in activities that integrated Mexican ethnic culture, parents mentioned wanting more opportunities for their adolescents to engage in these types of activities. Norma, a mother in the study, talked about wanting an activity that would teach her daughter to engage in traditional Mexican cultural activities, such as sewing and knitting. Parents also valued their adolescents’ participation in religious activities as they perceived that these activities reinforced Mexican cultural values. Particularly, Teresa responded the following when asked how her son’s participation in a religious activity was helping the family: “It has helped us very much that they know how to control their personality. They know that their parents should be respected, that their elders should be respected.” Teresa’s response denotes her value that her son’s religious activity was teaching him to be respectful of his parents and his elders, which aligns with the traditional Mexican cultural value of respeto (). All in all, parents thought it was beneficial when organized activities served as a context outside the home where adolescents were exposed to cultural knowledge and values congruent with their family ethnic culture.

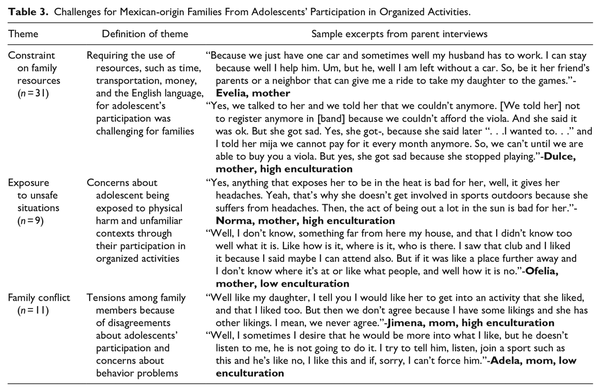

Challenges for Families

We found that the Mexican-origin parents in our study perceived the following challenges for families from their adolescents’ participation in organized activities: constraints on family resources, exposure to unsafe situations, and family conflict (Table 3).

Constraints on Family Resources

The challenge that was mentioned most often was constraints on family resources—specifically financial costs, transportation needs, interference with family routines, and balancing resources across multiple children (n = 31). This theme was partially determined based on previous literature that highlights the financial and transportation challenges of activities (; ) as well as inductive insights from the parents in this study about facing these challenges with multiple children. As parents explained, the financial cost of activities resulted in a burden for families that impeded enrollment and pushed some adolescents to drop out of activities. The financial cost of activities was especially a challenge for families whose adolescents wanted to participate in sport and art activities, as some of these activities required payment for equipment (e.g., musical instruments, uniforms). Moreover, parents in this study expressed difficulties transporting their adolescents when the family only had one car or when the family members who knew how to drive were unavailable. Constraints on family finances and transportation highlight the importance of addressing the accessibility of activities for Mexican-origin families.

When talking about the constraints on family resources, parents also talked about the interference of adolescents’ participation with family routines and the difficulty of managing resources across multiple children. For example, parents described that their adolescents’ participation in organized activities interfered with their job schedule, family dinner time, and the parents’ personal activities, such as going to church. Managing the family schedule was especially challenging when families had multiple children and adolescents participated in activities that required intensive time commitment, such as sports activities that required adolescents to regularly attend weekly practices and games. In the following excerpt, Elena and Fernando, a mother and father in the study, describe managing their family schedule:

It’s hard on our schedule because it’s once a week, it’s hard on the schedule because we have three kids and besides the you know, like right now, taking her to the morning club 7-8 and she can’t catch the bus, we have to take her and then we have to drop her off and pick her up for the horseback riding every Tuesday, so she’s going Tuesday, Thursday, Friday and you know that’s just one of our kids, then we have the other two and that’s very challenging time wise for us.

As this excerpt suggests, the time commitment of organized activities represented an overwhelming stress for families to balance with their family routines. Additionally, parents with multiple children, like Elena and Fernando, had to seriously consider the resources they had available, such as money, time, and transportation, for all their children when making decisions about any one of their children’s activities. Because of the interference with other family activities and the difficulty of managing resources across multiple children, families had to make challenging decisions about what activities to prioritize, which sometimes meant that adolescents could not attend an activity.

Exposure to Unsafe Situations

Though some parents felt activities offered protection for adolescents, other parents thought activities exposed them to unsafe situations, including exposure to physical harm and unfamiliar contexts (n = 9). This theme was developed based on deductive insights from previous literature about parents’ concerns for physical harm () and inductive insights from parents who discussed unsafe situations that had not been previously captured in the literature. Parents’ concerns ranged from more minor concerns, such as the risk of sun exposure, to more serious concerns, such as drug use. Parents were especially concerned about their adolescents being exposed to physical harm in sports activities. Particularly, parents perceived those activities like football, wrestling, and karate could lead to injuries, health problems, and aggression among peers. For example, a mother in the study, Luz, was concerned that her son might get injured in wrestling: “I think we always worry about injuries because that is a possibility so is one of the things we always tell him. You know to be careful sometimes they can’t do anything about it.” Parents were also concerned about adolescents’ potential exposure to places parents were not familiar with and people they did not know. Angela, a mother, mentioned the following about not allowing her daughter to go out in their neighborhood: “I don’t let her go out here because I think that we don’t all know each other [in the US]. And we all know each other there [in Mexico].” In summary, parents had concerns about their adolescents being exposed to situations they deemed unsafe through organized activities, which led parents to restrict adolescents’ participation. Overall, these findings suggest that some parents are concerned about adolescents’ safety at organized activities.

Family Conflict

The final family challenge was family conflict (n = 11). This theme was largely based on deductive coding as parents revealed unique insights about how their ethnic culture shapes their concerns about their adolescents’ participation in organized activities. Particularly, parents felt that adolescents’ activity participation may have contributed to family tensions due to disagreements about the activity and concerns about behavior problems. For example, parents had disagreements with their adolescents about the type of organized activity that they wanted their adolescents to participate in. Amelia, a mother in the study, recounted a disagreement she had with her daughter about her participation in a dance activity:

First, we argued because she said to me “why, why don’t you want me to dance? why don’t you want me to do this?” One day I brought her and paid the fee. We paid for the hour of dance and I stayed there with her watching what they were doing. I did not like the dance, first of all because the dudes and girls were dancing, I say no, I do not like that. And then there was an argument.

As Amelia explains, she did not approve of her daughter participating in dance because it involved her daughter dancing with boys, which led to an argument with her daughter, who did not understand her mother’s disapproval. This disagreement seemed to stem from a cultural and generational divide regarding gender norms between Amelia and her daughter. Another area of family conflict that parents encountered was adolescent problem behavior. One mother in the study, Maria, expressed concerns that her daughter acted “more like a rebel,” “talked back more,” and “[did] not do things whenever [Maria] asked her to” after she started participating in softball. As Maria describes, her daughter’s increasing disrespect led to tension with her daughter that made her consider taking her daughter out of softball. This tension contributed to a widening acculturation gap between Maria and her daughter, as Maria was concerned that her daughter’s behavior was not aligning with the Mexican ethnic cultural value of respeto. Overall, as shown in the examples of Amelia and Maria, the family conflict that occurred because of the adolescents’ activities strained parent-adolescent relationships and ultimately limited adolescents’ activity participation.

Differences Based on Parents’ Enculturation

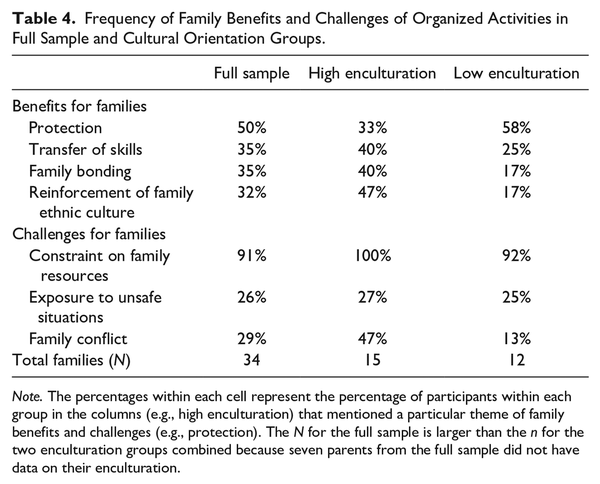

We considered whether the themes of family benefits and challenges varied based on parents’ enculturation (high enculturation: n = 15 parents and low enculturation: n = 12 parents). In Table 4, we provide the frequency of each theme for the two groups. In the text below, we discuss the main differences we found between the groups.

For the family benefits, we found parents in the high enculturation group more frequently reported family bonding and reinforcement of family culture as benefits compared to the low enculturation group. Specifically, over twice as many parents reported family bonding and reinforcement of family culture in the high enculturation group (40% and 47%) compared to parents in the low enculturation group (17% for both themes). These findings suggest that the degree to which the parents in the study aligned with the Mexican ethnic culture was related to the benefits they discussed. In terms of family bonding, parents with higher enculturation more commonly valued activities providing opportunities for family members to spend time together, which aligns with the value of familism that is prominent in Mexican ethnic culture (). Moreover, parents in the high enculturation group more commonly mentioned valuing organized activities that exposed their adolescents to cultural knowledge about typical Mexican activities (e.g., Spanish music) and cultural values such as respeto (i.e., respect for parents and elders). Essentially, compared to parents with a lower enculturation, parents with a higher enculturation were more likely to discuss the alignment between the activity and Mexican culture as a benefit to families.

For the family challenges, we found that parents with a higher enculturation (47%) reported family conflict as a challenge more than twice as much as parents with lower enculturation (13%). The instances of family conflict that parents with higher enculturation mentioned mostly involved disagreements about differences in parents’ and adolescents’ cultural values. For example, Teresa mentioned having a conflict with her son because he refused to attend catechism, a religious activity that aligned with Teresa’s high value of religiosity. Overall, the parents’ reports of family conflict suggest that the higher prevalence of family conflict as a challenge in the high enculturation group compared to the low enculturation group may stem from the perception that activities contribute to acculturation gaps between parents with high enculturation and their children (; ).

Discussion

Cultural-ecological theories (; ) suggest that adolescents’ participation in organized activities can shape family processes. In the case of Mexican-origin adolescents, the model of Latino youth development suggests that it is important to consider how culturally specific factors that capture the diversity among Mexican-origin adolescents and families may shape their experiences with organized activities (). The goal of this study was to examine parents’ perceptions of the benefits and challenges families can experience through their adolescents’ organized activity participation while considering whether parents’ perspectives differed based on their level of enculturation. We also considered how parents’ perspectives of the benefits and challenges of activities varied based on the activity type. The findings have implications for guiding organized activities that seek to address the challenges to adolescents’ participation that families face and design activities that are responsive to the cultural values and practices of Mexican-origin families.

In alignment with cultural-ecological theories (; ), parents in this study perceived that their adolescents’ participation in organized activities may have shaped family dynamics, relationships, and activities. For example, parents mentioned that organized activities helped promote harmonious family relationships through opportunities for family bonding and improvements in adolescents’ socioemotional skills (; ). Additionally, according to parents, their adolescents’ engagement in family chores and responsibilities improved as a result of their organized activity participation (; ). Thus, as a contribution to the literature, these findings suggest that the benefits of organized activities can extend beyond the participating adolescents to their families (). In contrast, we also found that some parents experienced tensions with their adolescents when they disagreed about what activity adolescents should participate in. Parents also perceived that the commitment required by organized activities in terms of time and resources constrained the ability of family members to participate in other valued activities, including family activities (e.g., dinner time), personal activities (e.g., going to church), and work obligations. Overall, our findings describe the complex and nuanced ways through which adolescents’ activity participation may shape family relationships and interactions.

We found that contextual characteristics of families and organized activities informed parents’ perceptions of the benefits and challenges of organized activities. For example, parents with multiple children expressed the overwhelming stress of balancing the required resources for participating in organized activities (e.g., transportation, financial cost) across all their children. These parents had to make difficult decisions on which activities for which children to support or deciding between a child’s activity and the overall family. Thus, it was particularly challenging for families with multiple children to support their adolescents’ participation in organized activities given the constraints on family resources. Furthermore, parents’ perceptions of the benefits and challenges of organized activities also depended on certain characteristics of organized activities. Particularly, parents valued sports activities that involved attending games or matches as it resulted in an opportunity for the family to spend time together. However, as documented in previous literature, parents in this study expressed that sport activities that required buying equipment and travel costs involved a substantial financial cost compared to other activities (; ). Extending from cultural-ecological theories (; ), we find that contextual characteristics, such as family size, the nature of the activities offered, and the activity cost, can shape the processes by which organized activities influence families.

We also found that parents’ adherence to Mexican ethnic culture, that is their level of enculturation, was related to their perceptions of the family benefits and challenges of their adolescents’ participation in organized activities. Particularly, parents with a higher enculturation to Mexican ethnic culture were more likely to mention benefits of organized activities that aligned with traditional cultural values of the Mexican culture, such as familism and respeto (; ). Additionally, Mexican-origin parents who were more enculturated were more concerned about a cultural mismatch between organized activities and their ethnic culture (; ). These findings suggest that the degree to which Mexican-origin parents follow Mexican ethnic cultural values, beliefs, and practices may shape their expectations of what their adolescents should gain from participating in organized activities (; ). Particularly, parents who are more enculturated may be more likely to support their adolescents’ participation in an activity that they perceive aligns with their Mexican ethnic culture. On the other hand, if enculturated parents perceive that an activity does not align with their Mexican ethnic culture, this may compromise parents’ decision to allow their adolescent to participate in that activity. As we found in our study, parents with relatively higher enculturation felt their adolescents’ organized activity participation contributed to a growing acculturation gap between them and their adolescents, which prompted some parents to limit adolescents’ participation in that activity (; ). Based on these findings, it is essential for organized activities to consider the ethnic culture of the families they serve, as parents’ perceptions of whether an activity aligns with their ethnic culture or not may ultimately determine whether an adolescent participates in an activity and the quality of their participation.

Practical Implications for Organized Activities

Our study findings have practical implications for organized activities that seek to support the development of Mexican-origin adolescents. Particularly, to maximize the developmental benefits for Mexican-origin adolescents, organized activities should take a culturally responsive approach to their programming that leverages the perspective of the families they serve, including their traditions, values, concerns, and ways of doing things (). Information from this study about the family benefits and challenges for Mexican-origin families can help organized activities develop practices that support the access, retention, and engagement of Mexican-origin adolescents and their families in their activities.

In the paragraph below, we recommend a series of culturally relevant practices that organized activities serving Mexican-origin adolescents can implement in their programming based on our findings.

First, we recommend that organized activities implement strategies to promote the recruitment and retention of Mexican-origin adolescents and families. For example, activity staff can conduct outreach events in the community that highlight the potential benefits for families of participating in their activities (e.g., promoting harmonious family relationships). Additionally, to help support the continued engagement of families, organized activities can regularly host family-focused events, such as a family game night or a fundraising event where families are invited to participate (), and develop activities that encourage adolescents to have conversations with their family and share cultural knowledge and stories from their families (; ). Lastly, given the challenges faced by families with multiple children, we recommend that organized activities consider how multiple sites can coordinate to facilitate participation of multiple children from one family. Particularly, activities could incorporate family discounts for activity fees, develop programming for youth across different age groups, or partner with programs that serve other age groups. Overall, implementing these practices can help incentivize adolescents’ enrollment and consistent participation, support family involvement, and improve the quality of participation ().

Following the model of Latino youth development (), it is important to consider the diverse values and beliefs among families who share the same ethnic heritage, such as the Mexican-origin families of this study. As we found in our study, the beliefs about the benefits and challenges of organized activities were different for parents who were more enculturated to Mexican ethnic culture compared to those who were less enculturated. Thus, to be culturally responsive, organized activities need to be responsive to the specific families they serve and not assume that families who share an ethnic heritage have homogenous cultural values and beliefs (). As shown in a recent study, organized activities that fall into assumptions about Latinx communities can misrepresent the culture of the adolescents and families they serve, which can be harmful for adolescents and families and can compromise their continued participation in the activity (). Through centering adolescent and family voices, organized activities can avoid developing activities that are culturally unresponsive and instead develop activities alongside families that support the developmental needs of Mexican-origin adolescents ().

Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study provides valuable insights about how adolescents’ participation in organized activities can contribute to benefits and challenges for Mexican-origin families, there are some limitations to consider. First, we did not examine adolescent gender as a relevant sociocultural factor in adolescent’s organized activity participation. There is empirical evidence that Latinx parents socialize their girls and boys differently in terms of their organized activity participation (). Moreover, previous research shows that there are gender differences in the types of activities that adolescents participate in as well as the benefits that adolescents obtain from their participation (, ; ). Thus, it is possible that the gender of Mexican-origin adolescents contributes to differences in parents’ perceptions of the family benefits and challenges of organized activities. Future work should examine the extent to which adolescent gender and gender socialization across families and organized activities can shape the experiences of Mexican-origin families with organized activities.

Although our study to some extent captured how contextual characteristics can inform parents’ perceptions about the family benefits and challenges of organized activities, it is valuable for future studies to further explore differences based on the type and characteristics of organized activities. In our study, about half of the adolescents involved in organized activities participated in sport activities. Our findings on the family benefits and challenges of organized activities may be underrepresenting the perspective of families involved in activities other than sports activities. For example, community-based organized activities, compared to sport activities, may have different characteristics in terms of the cost required for families and the support for family engagement. Thus, it is possible that we did not capture the full extent of family benefits and challenges across activity type because of the few students who participated in certain types of activities. Essentially, future research should further explore how differences across the types of activities that Mexican-origin students are involved in may differentially shape the experience of Mexican-origin families with organized activities.

It is also valuable to consider the time at which our data was collected. Since the 2009–2010 school year, which is when our study took place, major social events, such as the COVID-19 global pandemic, have transformed the U.S. society. It is possible that these major social events uniquely shaped the experience of Mexican-origin adolescents and families with organized activities in the current decade. Thus, it is valuable to further examine the extent to which our findings apply to U.S. adolescents and families in the present. Overall, our study contributes valuable insight to the existing literature about family and ethnic cultural processes that shape the organized activity participation of Mexican-origin adolescents (; ; ) that can inform future research that replicates this study with a more contemporary sample.

Conclusion

This study explored the perspectives of Mexican-origin parents about the family benefits and challenges associated with their adolescents’ participation in an organized activity, thereby extending the current literature focused on the benefits for the adolescents who attend. Our work suggests that organized activities can promote harmonious family relationships through opportunities for family bonding and the transfer of adolescent improved skills from activities to the home. Additionally, the challenges parents face concerning their adolescents’ activity participation, such as constraints on family resources, highlight the importance of organized activities taking a family systems approach when addressing access. Another valuable contribution to the literature is that we found that some parent perceptions of activities were informed by their adherence to Mexican ethnic culture. Lastly, although the families in this study shared an ethnic heritage, some of their beliefs of organized activities varied based on their cultural orientations. Our study has important implications for organized activities that strive to be culturally responsive to the Mexican-origin families and adolescents they serve. Ultimately, incorporating the perspective of parents and families can improve the experience of adolescents and families with organized activities and encourage them to continue participating.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was funded in part by the William T. Grant Young Scholars Award (#7936) to Sandra D. Simpkins and a William T. Grant Award (#181735) to Sandra D. Simpkins and Cecilia Menjívar. We also want to thank the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship for supporting Perla Ramos Carranza in their graduate studies.

Perla Ramos Carranza

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9007-6831

References

- Barnett L. A., Weber J. J. (2008). Perceived benefits to children from participating in different types of recreational activities. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 26(3), 1–20.

- Bean C. N., Fortier M., Post C., Chima K. (2014). Understanding how organized youth sport maybe harming individual players within the family unit: A literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(10), 10226–10268. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph111010226

- Bennett P. R., Lutz A., Jayaram L. (2012). Beyond the schoolyard: The Contributions of parenting logics, financial resources, and social institutions to the social class gap in structured activity participation. Sociology of Education, 85(2), 131–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040711431585

- Borden L. M., Perkins D. F., Villarruel F. A., Carleton-Hug A., Stone M. R., Keith J. G. (2006). Challenges and opportunities to Latino youth development: Increasing meaningful participation in youth development programs. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 28(2), 187–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986306286711

- Bronfenbrenner U., Morris P. A. (1998). The ecology of developmental processes. In Damon W., Lerner R. M. (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theory (5th ed., pp. 993–1028). Wiley.

- Cuellar I., Arnold B., Maldonado R. (1995). Acculturation rating scale for Mexican Americans-ii: A revision of the original ARSMA scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 17, 275–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/07399863950173001

- Driscoll M. W., Torres L. (2022). Cultural adaptation profiles among Mexican-descent Latinxs: Acculturation, acculturative stress, and depression. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 28(2), 248–258. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000503

- Erbstein N., Fabionar J. O. (2019). Supporting Latinx youth participation in out-of-school time programs: A research synthesis. Afterschool Matters, 29, 17–27.

- Ettekal A. V., Simpkins S. D., Menjívar C., Delgado M. Y. (2020). The complexities of culturally responsive organized activities: Latino parents’ and adolescents’ perspectives. Journal of Adolescent Research, 35(3), 395–426. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558419864022

- Fetters M. D., Curry L. A., Creswell J. W. (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48(6 Pt 2), 2134–2156. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12117

- Fredricks J. A., Eccles J. S. (2005a). Developmental benefits of extracurricular involvement: Do peer characteristics mediate the link between activities and youth outcomes? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34, 507–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-005-8933-5

- Fredricks J. A., Eccles J. S. (2005b). Family socialization, gender, and sport motivation and involvement. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 27(1), 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.27.1.3

- Fredricks J. A., Eccles J. S. (2008). Participation in extracurricular activities in the middle school years: Are there developmental benefits for African American and European American youth? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 1029–1043. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9309-4

- García A., Gaddes A. (2012). Weaving language and culture: Latina adolescent writers in an after-school writing project. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 28(2), 143–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2012.651076

- Gast M. J., Okamoto D. G., Feldman V. (2017). We only speak English here: English dominance in language diverse, immigrant after-school programs. Journal of Adolescent Research, 32(1), 94–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558416674

- Gonzales N. A., Fabrett F. C., Knight G. P. (2009). Acculturation, enculturation, and the psychosocial adaptation of Latino youth. In Villarruel F. A., Carlo G., Grau J. M., Azmitia M., Cabrera N. J., Chahin T. J. (Eds.), Handbook of U.S. Latino psychology: Developmental and community-based perspectives (pp. 115–134). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Grau J. M., Azmitia M., Quattlebaum J. (2009). Latino families: Parenting, relational, and developmental processes. In Villarruel F. A., Carlo G., Grau J. M., Azmitia M., Cabrera N. J., Chahin T. J. (Eds.), Handbook of US Latino psychology: Developmental and community-based perspectives (pp. 153–170). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Halgunseth L. (2019). Latino and Latin American parenting. In Bornstein M. H. (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Social conditions and applied parenting (Vol. 4, 3rd ed., pp. 24–56). Routledge.

- Hill C. E., Knox S., Thompson B. J., Williams E. N., Hess S. A., Ladany N. (2005). Consensual qualitative research: An update. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 196–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.196

- Iturbide M. I., Gutiérrez V., Munoz L., Raffaelli M. (2019). “They learn to Convivir”: Immigrant Latinx parents’ perspectives on cultural socialization in organized youth activities. Journal of Adolescent Research, 34(3), 235–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558418777827

- Kaufman J., Gabler J. (2004). Cultural capital and the extracurricular activities of girls and boys in the college attainment process. Poetics, 32(2), 145–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2004.02.001

- Kuperminc G. P., Thomason J., DiMeo M., Broomfield-Massey K. (2011). Cool Girls, Inc.: Promoting the positive development of urban preadolescent and early adolescent girls. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 32, 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-011-0243-y

- Kuperminc G. P., Wilkins N. J., Roche C., Alvarez-Jimenez A. (2009). Risk, resilience, and positive development among Latino youth. In Villarruel F. A., Carlo G., Grau J. M., Azmitia M., Cabrera N. J., Chahin T. J. (Eds.), Handbook of US Latino psychology: Developmental and community-based perspectives (pp. 213–233). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Lareau A., Weininger E. B. (2008). Time, work, and family life: Reconceptualizing gendered time patterns through the case of children’s organized activities1. Sociological Forum, 23(3), 419–454.

- Larson R. W., Hansen D. M., Moneta G. (2006). Differing profiles of developmental experiences across types of organized youth activities. Developmental Psychology, 42(5), 849–863. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.849

- Larson R. W., Pearce N., Sullivan P. J., Jarrett R. L. (2007). Participation in youth programs as a catalyst for negotiation of family autonomy with connection. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9133-7

- Leech N. L., Onwuegbuzie A. J., Combs J. P. (2011). Writing publishable mixed research articles: Guidelines for emerging scholars in the health sciences and beyond. International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches, 5(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.5172/mra.2011.5.1.7

- Lin A. R., Menjívar C., Vest Ettekal A., Simpkins S. D., Gaskin E. R., Pesch A. (2016). “They will post a law about playing soccer” and other ethnic/racial microaggressions in organized activities experienced by Mexican-origin families. Journal of Adolescent Research, 31(5), 557–581. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558415620670

- Lin A. R., Simpkins S. D., Gaskin E. R., Menjívar C. (2018). Cultural values and other perceived benefits of organized activities: A qualitative analysis of Mexican-origin parents’ perspectives in Arizona. Applied Developmental Science, 22(2), 89–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2016.1224669

- Mahoney J. L., Vandell D. L., Simpkins S., Zarrett N. (2009). Adolescent out-of-school activities. In Lerner R. M., Steinberg L. (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (Vol. 2, 3rd ed., pp. 228–269). John Wiley.

- McGovern G., Raffaelli M., Moreno Garcia C., Larson R. (2020). Leaders’ cultural responsiveness in a rural program serving Latinx youth. Journal of Adolescent Research, 35(3), 368–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558419873893

- Miles M. B., Huberman A. M., Saldana J. (2014). Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook (3rd ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). The promise of adolescence: Realizing opportunity for all youth. National Academies Press.

- Ngo B. (2017). Naming their world in a culturally responsive space: Experiences of Hmong adolescents in an after-school theatre program. Journal of Adolescent Research, 32(1), 37–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558416675233

- Perkins D. F., Borden L. M., Villarruel F. A., Carlton-Hug A., Stone M. R., Keith J. G. (2007). Participation in structured youth programs: Why ethnic minority urban youth choose to participate—or not to participate. Youth & Society, 38(4), 420–442. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118x06295051

- Pineda C. G., Nakkula M. J. (2015). Dancing ethnicity: A qualitative exploration of immigrant youth agency in an ethnically specific program. International Journal for Research on Extended Education, 2(2), 79–103. https://doi.org/10.3224/ijree.v2i2.19548

- Raffaelli M., Carlo G., Carranza M. A., Gonzalez-Kruger G. E. (2005). Understanding Latino children and adolescents in the mainstream: Placing culture at the center of developmental models. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2005(109), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.134

- Raffaelli M., Simpkins S. D., Tran S. P., Larson R. W. (2018). Responsibility development transfers across contexts: Reciprocal pathways between home and afterschool programs. Developmental Psychology, 54(3), 559–570. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000454

- Riggs N. R., Bohnert A. M., Guzman M. D., Davidson D. (2010). Examining the potential of community-based after-school programs for Latino youth. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45(3-4), 417–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-010-9313-1

- Saldaña J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage Publications.

- Simpkins S. D., Delgado M. Y., Price C. D., Quach A., Starbuck E. (2013). Socioeconomic status, ethnicity, culture, and immigration: Examining the potential mechanisms underlying Mexican-origin adolescents’ organized activity participation. Developmental Psychology, 49(4), 706–721. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028399

- Simpkins S. D., Fredricks J. A., Lin A. R. (2019). Families and engagement in afterschool programs. In Fiese B. H., Celano M., Deater-Deckard K., Jouriles E., Whisman M. (Eds.), APA handbook of contemporary family psychology. Applications of contemporary family psychology. (Vol. 2, pp. 235–248). American Psychological Association.

- Simpkins S. D., Riggs N. R., Ngo B., Vest Ettekal A., Okamoto D. (2017). Designing culturally responsive organized after-school activities. Journal of Adolescent Research, 32(1), 11–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558416666169

- Simpkins S. D., Vest A. E., Price C. D. (2011). Intergenerational continuity and discontinuity in Mexican-origin youths’ participation in organized activities: Insights from mixed-methods. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(6), 814–824. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025853

- Stodolska M., Sharaievska I., Tainsky S., Ryan A. (2014). Minority youth participation in an organized sport program: Needs, motivations, and facilitators. Journal of Leisure Research, 46(5), 612–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2014.11950345

- Sun X., Updegraff K. A., McHale S. M., Hochgraf A. K., Gallagher A. M., Umaña-Taylor A. J. (2021). Implications of COVID-19 school closures for sibling dynamics among US Latinx children: A prospective, daily diary study. Developmental Psychology, 57(10), 1708–1718. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001196

- Tudge J. R., Doucet F., Odero D., Sperb T. M., Piccinini C. A., Lopes R. S. (2006). A window into different cultural worlds: Young children’s everyday activities in the United States, Brazil, and Kenya. Child Development, 77(5), 1446–1469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00947.x

- Tudge J. R. H., Navarro J. L., Payir A., Merçon-Vargas E. A., Cao H., Zhou N., Liang Y., Mendonça S. (2022). Using cultural-ecological theory to construct a mid-range theory for the development of gratitude as a virtue. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 14(2), 157–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12432

- Valladares S., Ramos M. F. (2011). Children of Latino immigrants and out-of-school time programs. Child Trends. https://cms.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Child_Trends-2011_12_01_RB_ImmigrantsOSTProg.pdf

- Vandell D., Simpkins S., Wegemer C. (2019). Parenting and children’s organized activities. In Bornstein M. (Ed.), Handbook of parenting (Vol. 5, 3rd ed., pp. 347–379). Routledge.

- Vandell D. L., Larson R. W., Mahoney J. L., Watts T. W. (2015). Children’s organized activities. In Lerner R. M., Bornstein M. H., Leventhal T. (Eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science. Ecological Settings and Processes. (Vol. 4, 7th ed., pp. 305–334). John Wiley.

- Vélez-Agosto N. M., Soto-Crespo J. G., Vizcarrondo-Oppenheimer M., Vega-Molina S., García Coll C. (2017). Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory revision: Moving culture from the macro into the micro. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(5), 900–910. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617704397

- Villarreal V., Gonzalez J. E. (2016). Extracurricular activity participation of Hispanic students: Implications for social capital outcomes. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 4(3), 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2015.1119092

- Vygotsky L. S. (1987). The collected works of LS Vygotsky: Problems of the theory and history of psychology (Vol. 3). Springer Science & Business Media.

- Williams J. L., Deutsch N. L. (2016). Beyond between-group differences: Considering race, ethnicity, and culture in research on positive youth development programs. Applied Developmental Science, 20(3), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2015.1113880

- Yu M. V. B., Liu Y., Soto-Lara S., Puente K., Carranza P., Pantano A., Simpkins S. D. (2021). Culturally responsive practices: Insights from a high-quality math afterschool program serving underprivileged Latinx Youth. American Journal of Community Psychology, 68(3-4), 323–339. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12518