Burnout is a work-related stress syndrome characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment, which can negatively affect individuals across various professions, including health care workers, impacting their performance and quality of life. While the impact is felt by the individual, it originates in health systems. Human resources are widely recognized as the key factor responsible for health care quality, productivity, and performance. However, it is not only the quantity that matters; the qualitative state of human capital is also essential for delivering effective health care services.

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted the health system and global workforce, with high rates of burnout and mental health issues among health care workers reported across various countries. Health care professionals, particularly physicians and nurses, faced increased stress, burnout, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which has resulted in long-term depression, anxiety, and COVID-19 burden.

Approximately one in three physicians have experienced an episode of burnout in their careers, and many physicians and nurses are leaving their occupations as a result. In 2017, 31.5% of nurses in the United States (US) left health care due to burnout. Contributing factors include increased workloads, long work hours, exhaustion, fatigue, moral injury, lack of job control, and inadequate support.

The operating room (OR) is an area of vulnerability to traumatic events and health care worker burnout due to limited resources, high patient volumes, time and space constraints, and risk for human errors. Surgical procedures are known to be a major contributor to serious adverse events; when combined with health care provider burnout, there is increased potential for compromised patient safety, poor quality of care, and increased medical errors.

METHODS

This focused narrative review aimed to explore the effect of burnout in health care professionals working in the OR on patient safety and quality of care, with an emphasis on identifying overarching themes and qualitative insights. Searches of PubMed, CINHAL, Semantic Scholar, World Cat, Cochrane Library, and clinical trial registries (World Health Organization’s International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and ClinicalTrials.gov) were conducted in August 2023 and repeated in August 2024 using the keywords: burnout, patient safety OR patient care, patient outcomes OR mortality OR morbidity, operating room.

This review included full-text primary literature published in English between 2018 and 2024, focusing on health care professionals working in the OR, such as surgeons, anesthesiologists, and OR nurses. Eligible studies had to report original data using methodologies, including cross-sectional surveys, cohort studies, and randomized controlled trials. In addition, they needed to examine burnout or related constructs—such as emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment—and their impact on patient safety, quality of care, medical errors, communication breakdowns, and operational inefficiencies in the OR setting.

Publications were excluded if they were abstracts, editorials, letters to the editor, case reports, conference proceedings, or review articles. Non-English publications and studies outside the specified date range were also excluded. In addition, studies that did not focus on OR health care professionals or failed to assess burnout in relation to patient safety or quality of care in the OR were not considered. Research on burnout in non-OR settings was excluded unless it had direct and clear relevance to the OR context, as determined by the authors.

The manuscript selection process and data extraction involved one reviewer. While ideally data extraction would be performed by two independent reviewers to minimize bias, for narrative reviews, a single selection and extractor approach is acceptable. The extracted data were entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. The authors determined that sufficient review and interpretation of the literature had been performed when the narrative synthesis effectively captured the breadth and depth of the existing literature within the defined scope, identified consistent trends and divergent findings, and provided a comprehensive overview of the current understanding of the impact of burnout in the OR. The interpretation focused on contextualizing the findings within the broader literature on health care worker burnout and patient safety, highlighting the implications for clinical practice, and identifying areas for future research.

Given the nature of a narrative review and the reliance on published data, missing data within the primary studies was acknowledged as a limitation inherent to the source material and was not imputed or further investigated by the authors of this review. A meta-analysis, which requires statistical pooling of homogeneous data, and therefore studies with comparable designs, interventions, and outcome measures, was not applicable in this instance, since the studies included in the review varied significantly in terms of study design, burnout measurement tools, specific OR populations studied, and the variability of measured outcomes. Due to this heterogeneity, a meaningful quantitative synthesis of the data would have been unreliable and potentially misleading.

RESULTS

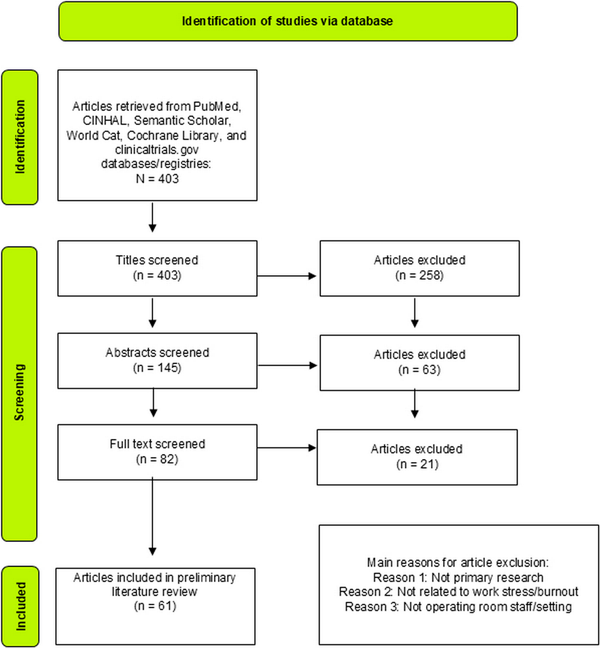

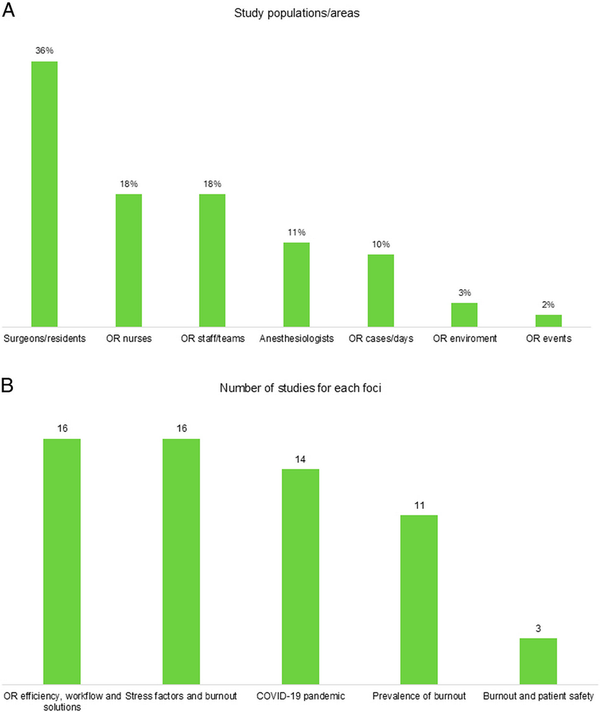

A total of 403 and 164 studies were retrieved in the search conducted in August 2023 and updated in August 2024, respectively (Fig. 1). Of these, 61 articles were included across both searches, originating from 23 different countries (Table 1), 7 OR populations or areas (Fig. 2A) and 5 main study foci (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 1

PRISMA diagram. This figure illustrates the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) diagram summarizing the identification of relevant studies for the review. It outlines the systematic process of screening and selection of articles, including the number of records identified, screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the final review. The flowchart provides a visual representation of the steps taken to ensure a comprehensive and transparent review of the literature on burnout among OR staff.

TABLE 1

Articles Included in the Review

| References | Location | Participants | Publication Date | Focus | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of burnout | |||||

| Afonso et al | US | Anaesthesiologists | 2024 | Burnout change since the onset of COVID-19 | 2698 |

| Velando-Soriano et al | Spain | OR nurses | 2024 | Burnout | 214 |

| Yang et al | China | Anaesthesiologists | 2023 | Burnout and job stress | 336 |

| Teymoori et al | Iran | OR nurses | 2022 | Occupational burnout | 18 |

| Ślusarz et al | Poland | Nurses: neurological and neurosurgical | 2022 | Job burnout, satisfaction, and work-related depression | 206 |

| Wang et al | China | OR nurses | 2022 | Work-related PTSD and burnout | 361 |

| Vargas et al | Italy | Anaesthesiologists and intensive care physicians | 2020 | Burnout | 859 |

| Faivre et al | France | Surgeons: orthopaedic and trauma | 2019 | Burnout | 441 |

| Sun et al | US | Anaesthesiology residents | 2019 | Burnout, Distress, and Depression | 5295 |

| Williford et al | US | Surgical residents and attendings | 2018 | Burnout and depression | 92 residents and 55 attendings |

| Li et al | China | Anaesthesiologists | 2018 | Burnout and job satisfaction | 2873 |

| COVID-19 pandemic | |||||

| Shalaby et al | Global | Surgeons | 2024 | Pre-during-post COVID burnout | 954 |

| Dhannoon and Nugent | Ireland | Surgical physicians | 2022 | Impact of COVID-19 on burnout | 65 |

| Fagerdahl et al | Sweden | Strategic sample of 12 operating room team members: surgeons, anaesthesiologist, specialist nurses, and nurse assistants | 2022 | Moral distress due to COVID-19 | 12 |

| Wei et al | US | OR nurses | 2022 | Burnout and epigenetic biomarker telomere length pre and during COVID-19 | 146 |

| Frigo et al | Italy | Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care physicians | 2022 | Burnout during COVID | 1009 |

| Matava et al | Canada | OR nurses, anaesthesiologists, service attendants, surgeons, and surgical trainees | 2022 | Experience of reducing COVID-19 surgical backlog | 82 |

| Appiani et al | Argentina | Clinical specialists, surgeons, emergency physicians and those with no direct contact with patients | 2021 | COVID effects on physicians | 305 |

| Caillet and Allaouchiche | France | Nurses, anaesthetists nurse, operating room nurses and health managers | 2021 | Prevalence of psychological disorders during COVID | 381 |

| Mavroudis et al | US | Surgeons: academic | 2021 | Experience during COVID | 337 |

| Mohammadi et al | Iran | OR staff | 2021 | Experience during COVID | 19 |

| Simon and Regan | Canada | Orthopaedic surgeons | 2021 | COVID-19 effects | 187 |

| D'Souza et al | Canada | Surgeons | 2021 | COVID-19 impact on mental health | 198 |

| Khattab et al | Global | Surgeons: spinal | 2020 | Impact of COVID-19 | 781 |

| Vallée et al | France | Residents and fellows of surgery | 2020 | COVID-19 impact on mental health | 1450 |

| Stress factors for burnout | |||||

| Chen et al | Taiwan | Nurses | 2024 | Parental role, family, work environment | 612 |

| Destrieux et al | France | Surgeons | 2024 | Work environment | 125 |

| Idrees et al | India | Surgeons | 2024 | Noise level in OR | 37 cases |

| Narayanan et al | New Zealand | Surgeons | 2024 | Music as a stressor | 74 cases |

| Behzad et al | Iran | OR medical staff | 2022 | Work-related physical discomfort | 10 |

| AlQhtani et al | Saudi Arabia | Surgical residents and consultants | 2022 | Shame-based learning in the surgical field | 70 |

| Jagetia et al | India | Surgeons: neurology | 2022 | Sex-difference in perceived stress | 93 |

| Mavroudis et al | US | Surgeons: academic | 2021 | Relationship between stress and sex | 337 |

| Verret et al | US | Surgeons, fellows, and residents: orthopaedic | 2021 | Drivers of burnout | 148 |

| Keyvanara et al | Iran | OR staff | 2020 | Burnout factors | 206 |

| Baumgarten et al | France | Neurosurgeons and residents | 2020 | Personal and psychosocial factors of burnout | 141 residents, 432 neurosurgeons |

| Min et al | China | OR | 2020 | OR noise | 3 hospitals |

| Wang et al | US | Surgical residents: vascular | 2020 | Sex-discrimination and burnout | 284 |

| Khan et al | Pakistan | Anaesthesiologist | 2019 | Job stress and burnout | 447 |

| Keyvanara et al | Iran | OR staff | 2019 | Effective factors on occupational burnout | 20 |

| Maddineshat et al | Iran | OR staff | 2017 | Disruptive behaviour | 144 |

| Burnout and patient safety | |||||

| Van Dalen et al | Unknown | Laparoscopic procedures | 2022 | Human factors affecting surgical patient safety | 35 cases |

| Lee et al | South Korea | OR nurses | 2020 | Patient safety culture | 122 |

| Arriaga et al | US | Critical events: anaesthesiology | 2019 | Critical events | 89 critical events |

| OR efficiency, workflow and solutions | |||||

| Wei et al | China | OR nurses | 2024 | Breathing meditation | 35 |

| Oh et al | Unknown | Surgical teams | 2024 | OR design | 3 OR teams |

| Taribagil et al | UK | Surgeons | 2023 | Dual surgeon operating | 85 |

| Arad et al | Israel | Surgical cases | 2022 | Teamwork in the surgery | 2184 direct observations |

| Orr et al | US | Surgical cases | 2022 | OR efficiency | 529 cases |

| Kim et al | South Korea | OR nurses | 2022 | Teamwork and burnout | 144 |

| Chenani et al | Iran | OR experts | 2022 | Technical performance in the OR | 26 |

| Kamande et al | US | Surgical cases | 2022 | Turnover time between cases | 2174 cases |

| Khorfan et al | US | Surgical residents: general | 2021 | Association of personal accomplishment with well-being | 6956 |

| Athanasiadis et al | US | OR teams | 2021 | OR room inefficiencies and delays | 96 OR cases |

| Kacem et al | Tunisia | OR staff: urology and maxillofacial | 2020 | Effect of music therapy | 5 functional operating room |

| Silver et al | US | Surgical technologists | 2020 | Surgical flow | 111 |

| Katafigiotis et al | Israel | Surgical cases | 2019 | Operating room time | 570 cases |

| Kougias et al | US | Operating suite | 2019 | OR efficiency | 207 operating days |

| Lindemann et al | US | Surgeries: liver transplants | 2019 | Resources utilization | 775 cases |

| Rangasamy et al | US | Surgeons, anaesthesiologist, nurses | 2019 | Meditation on stress | 910 |

FIGURE 2

Study characteristics: study populations (A) and primary foci (B) of the included studies. These figures present an overview of the study characteristics from the included studies: A provides a visual summary of the study populations/areas and OR settings explored in the studies, showing the diversity represented in the research on burnout among OR staff; B categorizes the main research foci of the studies. It highlights the key areas of investigation, such as burnout prevalence, psychological impact, and effects related to COVID-19, providing an insight into the major themes and issues addressed in the review literature. OR indicates operating room.

Prevalence of Burnout

Many studies reported a high prevalence of burnout in the OR (Table 2). In a large Italian cross-sectional survey of 1009 participants, nearly 40% experienced emotional exhaustion and 26% depersonalization, with 44% scoring low in personal accomplishment. The link between work-related traumatic events and depersonalization is well established. Surgical areas face significant burnout risk, with one survey reporting an 83% burnout rate due to social isolation. Another study found that 73.5% of surgeons experienced burnout, and 93.7% were stressed. Similarly, burnout was prevalent in the French neurosurgical community, with no significant differences between residents and neurosurgeons.

TABLE 2

Prevalence of Burnout Among OR Staff

| Profession | Country | Burnout Prevalence |

|---|---|---|

| Anesthesiologists | US | 67.7% high risk for burnout, 18.9% with burnout syndrome |

| Anesthesiologists | Pakistan | 50.3% burnout, 68.4% depersonalization, 39% emotional exhaustion |

| Anesthesiologists | China | 69% burnout rate |

| Anesthesiologists | Italy | 10.2% incidence of high-degree burnout |

| Anesthesiology residents and first-year graduates | US | 51% burnout, 32% distress, 12% depression |

| Anesthesiology and intensivists | Italy | 39.7% high emotional exhaustion, 25.8% high depersonalization |

| Anesthesiology and intensive care physicians | Italy | 79.9% moderate degree of burnout |

| Nurses: neurological and neurosurgical | Poland | 32% work-related burnout |

| Nurses: OR, perioperative, and labor and delivery | US | 70.5% burnout rate |

| Nurses: OR | France | 64% anxiety disorder, 45% depression, 45% PTSD |

| Nurses: OR | US | Nurses’ cellular biomarker, telomere length, shorter during COVID-19 |

| Nurses: OR | Spain | 17.3% experienced high levels of burnout; 29.4% high levels of emotional exhaustion, 25.7% depersonalization, 28% low levels of personal accomplishment |

| Neurosurgeons and residents | France | 49% burnout prevalence |

| Surgeons | Canada | 64% reported increased stress or anxiety due to pandemic |

| Surgeons: orthopedic and trauma | France | 39% burnout symptomatology |

| Surgical physicians | Ireland | 83% increased risk of burnout during the pandemic |

| Surgical residents | US | 30% met high-risk criteria for burnout |

| Surgical residents and attendings | US | 75% of residents met criteria for burnout |

| Surgical residents and consultants | Saudi Arabia | 75.9% residents, 80.5% consultants shamed |

| Clinical specialists, surgeons, emergency physicians | Argentina | 73.5% burnout syndrome |

Burnout among anesthesiologists has been extensively studied. In the United States, a survey of 5295 anesthesiology residents and first-year graduates found that 51% were burnt out, 32% distressed, and 12% depressed. An Italian study of 859 anesthesiologists reported a 10.2% incidence of high-degree burnout, marked by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment. A recent study of 2698 US anesthesiologists found high burnout rates, with many considering leaving their jobs due to burnout and staffing shortages. In China, a 69% burnout rate among 2873 anesthesiologists was reported. Similarly, a US post-COVID-19 cross-sectional study indicated that 67.7% of anesthesiologists were at high risk for burnout and 18.9% had burnout syndrome, and in Pakistan, 39% of anesthesiologists experienced emotional exhaustion, 68.4% depersonalization, and 50.3% burnout in personal achievement.

Other subgroups within the OR workforce also face increased burnout risk. A French study found that OR nurses had the highest prevalence of psychological disorders during COVID-19, with 64% experiencing anxiety, 45% depression, and 45% PTSD. Likewise, research in China revealed that OR nurses exposed to specific or multiple work-related traumatic events were at high risk for burnout.

Burnout prevalence rates varied slightly across countries, peaking during the pandemic. Irish surgical physicians and American OR nurses reported the highest levels at 83% and 70.5%, respectively. In France, studies found burnout rates between 36% and 49%, focusing on anxiety, depression, and insomnia among surgical staff. Similarly, studies from Poland and the US reported rates of 32% and 51%, respectively, showing slight global variations in burnout among health care professionals (Table 2).

Several studies explored sex differences in surgeon burnout. Wang et al found that 38% of female residents experienced sex-based discrimination, much higher than the 14% reported by male residents. In addition, 25% of female residents reported being sexually harassed during training, compared with only 1% of males. Nearly half of the participants experienced or witnessed sex-based discrimination and bias, leading to burnout. Similarly, female surgeons experienced higher stress levels during COVID-19 compared with their male counterparts (n=335), even after adjusting for parental and training status (P<0.001). Another study identified that being female was a significant risk factor for mental health compromise in the OR.

COVID-19 Pandemic

The pandemic had a global impact and notably impacted the OR wait times and increased the socioeconomic burden. However, only one study in this review compared burnout before and during the pandemic, surveying 954 surgeons globally. The total burnout score was reported as mean (SD) 18.05±5.41 prepandemic and 19.33±6.51 during the pandemic (P<0.001). In total, 66.5% felt that their roles had been diminished, and 41% were reassigned to nonsurgical tasks. During the pandemic, in the US, a 70.5% burnout rate was reported among nurses, while in Ireland, 83% of surgical staff were at increased risk of burnout. Similarly, in Argentina, a study of 302 physicians found high levels of stress (93.7%), burnout (73.5%), anxiety (44%), and depression (21.9%) during the pandemic.

Physicians and nurses were significantly affected by the pandemic. In France, Vallée et al found that insufficient training among young surgeons was linked to mental health disorders. French orthopedic surgeons experienced 39% burnout, affecting their quality of life. Some resident surgeons reported shame and depression, while others conversely felt accomplishment. Stress levels decreased with enhanced safety measures, but some faced income loss and fear of infecting patients and their own families with COVID-19.

On the other hand, nurses showed gradual burnout due to ongoing tension, exacerbated by unprofessional behavior, equipment shortages, anxiety, and difficult tasks. In one study, 45% of French OR nurses reported PTSD during COVID-19, and faced exhaustion, lack of support, professional challenges, and organizational obstacles, including insufficient pandemic-related guidelines.

Stress Factors for Burnout

Various stress factors potentiating burnout were identified, including personality and professional practice, internal/external environment plus organizational, interpersonal, occupational, and individual factors. In a US survey, 51% of anesthesiology residents and first-year graduates reported burnout, 32% distress, and 12% depression, with heavy workload and student debt increasing risk, while workplace resources and work-life balance reduced it. Similarly, 79% of vascular surgery residents (N=284) reported a negative workplace, and anesthesiologists cited job dissatisfaction, long hours, poor sleep, and poor physical health as burnout drivers. Post-COVID-19, a US study found burnout worsened by staffing shortages and lack of support, while workload and city of practice were stressors in Pakistan. Nurses faced stress from night shifts, equipment shortages, inadequate training, 24-hour shifts, anxiety, emotional exhaustion, COVID-19 patient interactions, musculoskeletal issues, and disruptive behavior.

Burnout stress factors varied by country. In Iran, organizational issues and personal factors like musculoskeletal disorders were significant. Studies from France, Poland, Iran, India, and the US highlight stressors such as high workload, organizational indifference, and poor work-life balance, leading to higher burnout rates among surgical staff. In Spain, 17.3% of OR nurses experienced high burnout levels associated with personality traits (neuroticism and depression) and being single/divorced males, suggesting potential risk groups for early detection. Similarly, a Taiwanese study of 612 nurses found higher burnout in those who were younger than 43 years old and single.

Burnout and Patient Safety

Few studies directly link burnout to patient safety incidents. Instead, they examine individual or organizational aspects that could lead to safety events. One study analyzed 89 critical events in a year and found a connection between the lack of debriefing and communication failures in the OR. Nearly half of these OR-related events occurred outside of the OR, varying in severity from cardiac arrest to communication breakdowns.

OR events were indirectly linked to patient safety concerns. For example, anesthesia delays and missing items, occurring in 19% of cases, and prolonged surgery times. Surgeons and anesthesiologists influenced timely OR turnover times, and communication failures (reported by 65% of surgeons) disrupted surgical flow. In addition, staff turnover was found to interrupt teamwork, as reported by 73% of surgeons.

OR Efficiency, Workflow, and Solutions

Several studies revealed inefficiencies in OR scheduling, surgical flow disruptions, OR turnover times and room characteristics. One study explored performance-shaping factors and human error, while another aimed to reduce OR delays with novel surgical applications. OR design has been linked to stress levels in surgical teams, highlighting the importance of patient flow, organization, and equipment access.

Interestingly, 79% of surgeons considered using a second surgeon (dual surgeon operation) as a viable solution; 89% believed it would reduce fatigue, 84% felt it would boost confidence, 77% thought it would enhance decision-making, 69% expected fewer technical errors, and 66% saw the potential for better communication and teamwork.

Behavioral techniques have been tested to improve mental well-being and job performance. A study of nearly 1000 participants, 28% of whom were anesthesiologists, found that meditation improved mood and reduced negative emotions in the OR. Another study found that meditative breathing helped to improve nurses’ mental well-being and job performance, while intraoperative music did not negatively affect performance. Three studies also reported solutions: a data-driven surgical scheduling system, music therapy to reduce stress and organizational strategies focusing on leadership and support.

DISCUSSION

This review of recent studies on OR staff burnout reveals high prevalence rates, especially among anesthesiologists, with significant emotional exhaustion and decreased personal accomplishment reported globally. The COVID-19 pandemic intensified these issues, with notable increases in burnout among both surgical and nursing staff during the pandemic. Sex differences in burnout were highlighted, showing higher stress levels in, and discrimination of, female staff.

Variations in burnout prevalence among OR professionals were reported across different countries, but these differences may not solely reflect true disparities in burnout levels. Instead, they could be influenced by multiple factors, including genuine differences in working conditions and health care systems, inconsistencies in measurement tools and methodologies, and cultural variations in how burnout is perceived and reported.

Lasting Effects of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted the OR workforce, exacerbating distress due to virus risk, quarantine, social stigma, and family concerns, compounded by surgical cancellations that caused workflow disruptions and a backlog that extended long after pandemic conditions ended.

Postpandemic research found that 67.7% of US anesthesiologists were at high risk for burnout, with 18.9% experiencing burnout syndrome and 78.4% reporting persistent staffing shortages. Not surprisingly, 36.0% planned to leave their jobs within 2 years. Coronaphobia contributed significantly to stress and family suffering, the impact of which extended beyond the health care professional and resulted in reciprocal and cumulative family suffering.

PTSD in OR staff is understudied; however, the Protec-Cov study reported that 18% of French doctors had significant post-COVID PTSD symptoms due to increased workload and isolation, and the HERO study of 2038 health care workers found younger workers and nurses had more PTSD symptoms compared with their older and physician counterparts during the COVID-19 pandemic. In intensive care settings, PTSD prevalence soared from 3.3% to 24% prepandemic to 16% to 73.3% postpandemic, with a rate of 24.3% reported in a 2023 survey of health care workers. These professionals faced unique risk factors such as constant confrontation with death, fear of infecting patients and family members, care unpredictability, COVID-19-related insecurity, increased workload, lack of professional recognition, and isolation due to lockdowns.

Postpandemic, one third of hospital doctors suffering from PTSD felt they needed psychological support, yet only 31% of these received it. Effective communication, protection, resources, and social support are crucial for mitigating long-term PTSD, highlighting the need for early intervention and support.

The pandemic’s impact extends beyond immediate stress, with many health care workers experiencing persistent psychological distress. Ongoing support systems, such as access to mental health services and peer support groups, are crucial for addressing these long-term effects. In addition, organizational policies that prioritize staff well-being, such as flexible work schedules and adequate rest periods, can help mitigate the ongoing impact of the pandemic. For example, hospitals can implement regular mental health check-ins and provide access to confidential counseling services. These system-level strategies can help lower job stress and promote quality of life for health care professionals working in high-stress environments.

High-risk Populations

In our review, surgeons, anesthesiologists, and nurses were the primary groups experiencing burnout, with sex-related factors appearing to play a notable role. Female surgeons reported experiencing higher levels of sex-based discrimination, bias, and sexual harassment compared with their male counterparts, and reported greater stress. Factors such as sex-based hierarchies in the OR, alongside potential pay gaps and reduced autonomy, may contribute to these experiences. Research on female neurosurgeons suggested that burnout risk is linked to being a resident and having fewer children, while a broader range of elements, including work duties, experience, age, sex, and marital status, also play a role. Interestingly, our review noted a finding of higher burnout risk among single or divorced males, while other studies have indicated higher burnout rates and lower satisfaction among female family physicians. Despite differing findings on specific risk factors, there is consensus that female physicians often carry a greater burden of responsibilities outside of work. As female medical students now outnumber males, yet remain underrepresented in surgical specialties, the increasing number of female applicants to surgical residencies underscores the growing urgency of addressing sex equity within the OR.

While targeted interventions may help address specific at-risk groups, broader, systemic changes are needed to tackle the deep-rooted cultural and societal sex-based challenges faced in the OR. Addressing these issues requires fundamental organizational and cultural shifts to create a more supportive and equitable work environment for all OR professionals.

Impact on Patient Safety

Occupational stress and burnout are known to significantly impair cognitive function, leading to decreased attention, reduced problem-solving abilities, depression, and compromised decision-making. This impairment directly elevates the risk of surgical errors and compromises patient safety. Analysis of surgical errors has revealed a complex interplay of contributing factors, encompassing individual clinician pressures like time constraints, interruptions, and exhaustion, alongside systemic issues such as communication breakdowns, staffing inconsistencies, organizational lapses in specimen handling, medical record inaccuracies, and errors in clinical judgment.

These connections are further illustrated by studies demonstrating that physician and nurse burnout are associated with an increase in the risk of medical errors. Systematic reviews evaluating older studies have reported that surgeon burnout is associated with a 2.5-fold increase in risk of medical errors and poorer patient safety, while a meta-analysis showed a 66.4% probability that high burnout levels lead to worse safety outcomes. A second meta-analysis of 5234 records found burnout was linked to increased patient safety events, lower patient satisfaction, and diminished care quality.

Communication, a key human factor contributing to medical errors and a factor contributing to 43% of malpractice claims in the United States, has dire consequences in the OR if not managed effectively. When communication fails, harm is caused to patients, staff, and hospitals, along with longer stays and wasted resources. Stressed and emotionally drained staff may exhibit poor communication skills, leading to misunderstandings, misinterpretations, and a breakdown in teamwork. A significant proportion (15%) of communication failures in surgical settings involve purpose failures, indicating a breakdown in the intended message. Communication errors have also been linked to increased stress and excessive noise in the OR, and inadequate staffing and increased staff turnover linked to poor teamwork. Interestingly, the best communication skills in the OR were found in nurses, staff older than 51 years, and those with >21 years of work experience.

Surgery demands extensive teamwork and coordination, and lower burnout rates are associated with better patient safety culture, job satisfaction, and working conditions. Interestingly, poor teamwork, manifested by disrespect, rudeness, and disagreements on patient care, can contribute to patient harm by escalating team tension and diminishing operational efficiency. Similarly, high staff turnover can significantly affect patient outcomes. In a recent retrospective study of National Health Service acute trusts in England (2010–2019), higher turnover rates of nurses and senior doctors were associated with increased risks of patient mortality within 30 days of emergency admissions. Specifically, a 1 SD increase in nurse turnover was associated with a 0.052 percentage point increase in all-cause emergency admission mortality (95% CI: 0.037-0.067), and a 1 SD increase in senior doctor turnover was associated with a 0.019 percentage point increase in emergency mortality (95% CI: 0.006-0.033). The study, analyzing data from ~236,000 nurses, 41,800 senior doctors, and 8.1 million admitted patients, revealed a significant correlation between staff turnover and patient mortality. Importantly, staff turnover has been linked to burnout.

Staff experiencing burnout may be less likely to report errors, voice concerns, or participate in safety initiatives. Importantly, the risk of significant harm to patients increases when medical errors go unreported. By implementing strategies and policies to mitigate burnout, health care institutions have the potential to enhance communication, improve leadership and support of staff, and ensure adequate resources to provide safe and effective care.

Improving Efficiency

In 2011, surgery hospitalizations accounted for 48% of total hospital costs in the US, highlighting the potential for efficiency improvements in the OR to reduce costs, boost productivity, and free up provider time. One approach proposed is using a parallel flow pathway, where care in the induction room continues while the OR is cleaned, which reduces turnover time and increases daily OR cases without compromising patient safety.

Studies have also identified wasted time and resources in the OR, with surgical waste comprising 20% of supply costs and circulating nurses spending 26% of their time outside the OR. In a survey of over 1500 US nurse practitioners, 70% reported burnout or depression, with 58% attributing it to bureaucratic tasks like charting and paperwork.

Solutions that improve time management and decrease waste, such as procedure packs, hold value. Customizable surgical packs, which are tailored to specific interventions, can enhance efficiency and reduce costs by ensuring only necessary tools are available. Similarly, integrating digital solutions, such as patient flow and automation of surgical pathways to provide real-time location systems that claim to increase OR utilization by 12.5% within 2 years and reduce waitlists—could positively influence efficiency and reduce costs.

High-stakes Environment

Beyond the significant influence of systemic factors, the intrinsic nature of working in the OR carries a substantial emotional weight that contributes to burnout. The constant exposure to critical and often life-threatening patient conditions, the emotional toll of witnessing suffering and, at times, mortality, and the inherent pressure associated with preventing errors in high-stakes procedures can lead to significant psychological distress. Health care professionals in the OR often bear the responsibility for critical decisions under time constraints, and the emotional aftermath of both successful and unsuccessful interventions can accumulate over time, contributing to emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. While systemic improvements are crucial for building resilience, acknowledging and addressing the direct emotional impact of these inherent aspects of OR work is equally important for a comprehensive understanding of burnout in this setting.

System-based Solutions

To effectively mitigate burnout and enhance patient safety in the OR, a comprehensive approach focusing on system-based solutions is essential. Promoting a culture of psychological safety, where staff feel supported and comfortable raising concerns without fear of reprisal, is vital for open communication and proactive problem-solving. In addition to strong leadership that prioritizes staff well-being, health systems can create a culture where burnout is recognized and addressed proactively. This foundation enables the implementation of other critical system changes.

Ergonomic human factor improvements, such as optimized equipment layout and reduced noise levels, can significantly decrease physical and mental strain on OR staff. Adjustable workstations, strategically placed equipment, and noise-reducing materials can create a more efficient and less stressful work environment.

Team-based simulation training can enhance communication, motivation, and coordination skills, reducing the likelihood of errors and improving teamwork. These simulations allow OR teams to practice complex scenarios, identify communication breakdowns, and refine their collaborative skills in a safe and controlled setting.

Furthermore, the integration of digital tools, such as electronic trigger tools, checklists, and real-time feedback systems, can improve surgical process adherence, minimize errors, and streamline workflows. Ideas, such as the digital OR and black box technology, are broadening the horizon on integration of technology in the OR. Innovative solutions can reduce administrative burden, improve information flow, and provide timely feedback to OR staff, enhancing efficiency and reducing the potential for human error. However, implementing innovative digital solutions in the OR still faces barriers, including the need for extensive interdisciplinary collaboration, standardized data protocols, increased acceptance of video recording, and robust ethical and legal frameworks for patient data protection.

Preventing Burnout

Context-specific interventions tailored to each country’s health care system are essential for mitigating burnout and promoting well-being among health care professionals worldwide.

Strategies, such as reducing workload, limiting duty hours, ensuring adequate staffing, and offering flexible schedules, can improve job satisfaction and reduce burnout. In addition, individual-focused interventions, including stress management and mindfulness, have also enhanced well-being.

Our review highlights the importance of addressing stress and working conditions to improve safety attitudes and patient outcomes in the OR. Effective strategies include providing adequate training and protective equipment, managing disruptive behavior, and fostering psychological safety in the OR. In addition, integrating process groups into surgical training can help manage work-related stress and improve mental health. In response to burnout, the CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has introduced the WellBQ questionnaire and Impact Wellbeing Guide to support hospital leaders in improving employee mental health.

Expert Opinion

This section provides a novel perspective of how experts view this issue from a clinical standpoint, and how effective practices can reduce burnout and improve care quality. Combining research insights with clinical perspectives, we highlight the critical need for systemic changes to support health care workers and ensure high-quality care.

In today’s health care environment, the link between human resource management (HRM) and the well-being of health care professionals is increasingly critical. Health care institutions rely on dedicated staff to care for individuals during illness and vulnerability, making staff well-being essential for quality care. Despite this, high rates of burnout, anxiety, depression, and other psychological disorders are prevalent, a problem worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our review highlights the strategic importance of effective HRM. Practices related to retention, such as training, workload management, work-life balance, and overall well-being, are crucial for preventing burnout. Implementing these practices requires collaboration among top management, line managers, HR specialists, employee representatives, and external consultants to create a supportive environment. However, challenges persist in implementing HRM practices due to organizational issues; top management often prioritizes financial and quality metrics over HRM. Medical professionals in line management roles frequently lack the necessary managerial skills, and traditional abusive training cultures further exacerbate the problem. In addition, HRM specialists often lack the credibility needed to be strategic assets.

The pandemic has intensified pressures on health care workers, making it urgent to address these issues holistically. Psychological problems affect decision-making, focus, and empathy, compromising patient safety, especially in sensitive areas such as the OR. Investing in mental and emotional well-being is essential for maintaining high-quality care and a supportive work environment.

Training and retaining health care professionals is costly and challenging. Addressing the loss of staff due to burnout and psychological issues is crucial. Although numerous performance indicators exist, reliable metrics for assessing psychological well-being and its impact on care quality are lacking. Re-evaluating working conditions, shift schedules, and protocols is necessary to manage burnout effectively. By focusing on both immediate stressors and long-term strategies for worker well-being, we can ensure that health care professionals have the support they need to deliver optimal care while maintaining their own health.

Limitations

This review has several limitations. The focus on English language studies from 2018 to 2024 may introduce language and publication bias, excluding relevant research outside this scope. Significant heterogeneity in study designs, OR populations, burnout measurement tools, and reported outcomes prevented a meta-analysis, limiting findings to broad trends and qualitative insights. The underrepresentation of studies from low-income and middle-income countries limits generalizability beyond high-income settings. In addition, few studies directly measured patient safety outcomes, relying instead on associated risk factors. Lastly, international prevalence comparisons are complicated by differences in measurement tools, cultural perceptions, and health care systems.

CONCLUSIONS

Burnout among health care workers, especially in high-stress settings like the OR, significantly impacts both staff well-being and patient safety. The COVID-19 pandemic has intensified these issues, increasing burnout, anxiety, and other psychological disorders. Effective HRM practices, such as improved training, workload management, and work-life balance, are crucial in addressing and preventing burnout. Our review underscores the need for a comprehensive approach to enhance working conditions and support OR staff well-being. The high prevalence of burnout among surgeons, anesthesiologists, and OR nurses demands collaboration between health care leaders, HRM specialists, and staff. Implementing strategies to reduce burnout and improve job satisfaction will, in turn, enhance patient safety and care quality. Investing in mental and emotional well-being, alongside tailored surgical solutions, is essential for sustaining high-quality health care. This requires reassessing organizational practices, strengthening support systems, and allocating adequate resources. By focusing on both immediate and long-term solutions, health care institutions can support their workforce and ensure optimal care delivery while maintaining staff health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Clare Koning, PhD, and Sheridan Henness, PhD (Rx Communications, Mold, UK) for medical writing support.

REFERENCES

1

De Hert S. Burnout in healthcare workers: prevalence, impact and preventative strategies. Local Reg Anesth. 2020;13:171–183.2

Ribeiro B, Scorsolini-Comin F, de Souza SR. Burnout syndrome in intensive care unit nurses during the COVID 19 pandemic. Rev Bras Med Trab. 2021;19:363–371.3

Verret CI, Nguyen J, Verret C, et al. How do areas of work life drive burnout in orthopaedic attending surgeons, fellows, and residents? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2021;479:251–262.4

Murthy VH. Confronting health worker burnout and well-being. New England Journal of Medicine. 2022;387:577–579.5

Hampel K, Hajduova Z. Human resource management as an area of changes in a healthcare institution. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2023;16:31–41.6

Halder N. Investing in human capital: exploring causes, consequences and solutions to nurses' dissatisfaction. J Res Nurs. 2018;23:659–675.7

Wei H, Aucoin J, Kuntapay GR, et al. The prevalence of nurse burnout and its association with telomere length pre and during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0263603.8

Appiani FJ, Rodríguez Cairoli F, Sarotto L, et al. Prevalence of stress, burnout syndrome, anxiety and depression among physicians of a teaching hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2021;119:317–324.9

Vallée M, Kutchukian S, Pradère B, et al. Prospective and observational study of COVID-19's impact on mental health and training of young surgeons in France. Br J Surg. 2020;107:e486–e488.10

Dhannoon A, Nugent E. Burnout among surgical staff at a tertiary hospital one year from the start of COVID-19 pandemic. Irish journal of medical science. 2022;191:S229.11

Matava C, So JP, Hossain A, et al. Experiences of health care professionals working extra weekends to reduce COVID-19-related surgical backlog: cross-sectional study. JMIR Perioper Med. 2022;5:e40209. doi:10.2196/4020912

Simon MJK, Regan WD. COVID-19 pandemic effects on orthopaedic surgeons in British Columbia. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021;16 2021-12-01. doi:10.1186/s13018-021-02283-y13

Rollin L, Guerin O, Petit A, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder in hospital doctors after the COVID-19 pandemic. Occup Med (Lond). 2024;74:113–119.14

Caillet A, Allaouchiche B. Intensive care nurses, psychological disorders and COVID-19. The COVID Impact National Study. Prat Anesth Reanim. 2021;25:103–109.15

Liu H, Zhou N, Zhou Z, et al. Symptoms of post traumatic stress disorder and their relationship with the fear of COVID−19 and COVID−19 burden among health care workers after the full liberalization of COVID−19 prevention and control policy in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23.16

Youssef D, Youssef J, Abou-Abbas L, et al. Prevalence and correlates of burnout among physicians in a developing country facing multi-layered crises: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep. 2022;12:12615.17

Wang J, Mao F, Wu L, et al. Work-related potential traumatic events and job burnout among operating room nurses: independent effect, cumulative risk, and latent class approaches. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78:2042–2054.18

Mohammadi F, Tehranineshat B, Bijani M, et al. Exploring the experiences of operating room health care professionals' from the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Surgery. 2021;21:434.19

de Cordova PB, Johansen ML, Grafova IB, et al. Burnout and intent to leave during COVID-19: a cross-sectional study of New Jersey hospital nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2022;30:1913–1921.20

Shah MK, Gandrakota N, Cimiotti JP, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with nurse burnout in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2036469.21

Daryanto B, Rahmadiani N, Amorga R, et al. Burnout syndrome among residents of different surgical specialties in a tertiary referral teaching hospital in Indonesia during COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2022;14:100994.22

Lee J, Aoude A, Alhalabi B, et al. Can an emergency surgery scheduling software improve residents’ time management and quality of life? McGill Journal of Medicine. 2022;20.23

Sami A, Waseem H, Nourah A, et al. Real-time observations of stressful events in the operating room. Saudi J Anaesth. 2012;6:136–139.24

Kinyuru Ojuka D, Okutoyi L, C Otieno F. Communication in surgery for patient safety. Vignettes in Patient Safety - Volume 4 [Working Title]. IntechOpen; 2019.25

Garcia CL, Abreu LC, Ramos JLS, et al. Influence of burnout on patient safety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55. doi:10.3390/medicina5509055326

Jun J, Ojemeni MM, Kalamani R, et al. Relationship between nurse burnout, patient and organizational outcomes: Systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;119:103933.27

Salyers MP, Bonfils KA, Luther L, et al. The relationship between professional burnout and quality and safety in healthcare: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:475–482.28

Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251:995–1000.29

Mangory KY, Ali LY, Rø KI, et al. Effect of burnout among physicians on observed adverse patient outcomes: a literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:369.30

Baumeister RF, Leary MR. Writing narrative literature reviews. Rev Gen Psychol. 1997;1:311–320; 1997/09/01. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.1.3.31131

Sukhera J. Narrative reviews: flexible, rigorous, and practical. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14:414–417.32

Hernandez AV, Marti KM, Roman YM. Meta-analysis. Chest. 2020;158:S97–S102.33

Frigo MG, Petrini F, Tritapepe L, et al. Burnout in Italian anesthesiologists and intensivists during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey. Minerva Anestesiol. 2023;89:188–196.34

Baumgarten C, Michinov E, Rouxel G, et al. Personal and psychosocial factors of burnout: a survey within the French neurosurgical community. Plos One. 2020;15:e0233137.35

Sun H, Warner DO, Macario A, et al. Repeated cross-sectional surveys of burnout, distress, and depression among anesthesiology residents and first-year graduates. Anesthesiology. 2019;131:668–677.36

Vargas M, Spinelli G, Buonanno P, et al. Burnout among anesthesiologists and intensive care physicians: results from an Italian National Survey. Inquiry. 2020;57:46958020919263.37

Afonso AM, Cadwell JB, Staffa SJ, et al. U.S. Attending anesthesiologist burnout in the postpandemic era. Anesthesiology. 2024;140:38–51.38

Li H, Zuo M, Gelb AW, et al. Chinese anesthesiologists have high burnout and low job satisfaction: a cross-sectional survey. Anesth Analg. 2018;126:1004–1012.39

Khan FA, Shamim MH, Ali L, et al. Evaluation of ob stress and burnout among anesthesiologists eorking in academic institutions in 2 major cities in Pakistan. Anesth Analg. 2019;128:789–795.40

Faivre G, Marillier G, Nallet J, et al. Are French orthopedic and trauma surgeons affected by burnout? Results of a nationwide survey. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2019;105:395–399.41

Ślusarz R, Filipska K, Jabłońska R, et al. Analysis of job burnout, satisfaction and work-related depression among neurological and neurosurgical nurses in Poland: a cross-sectional and multicentre study. Nurs Open. 2022;9:1228–1240.42

Wang LJ, Tanious A, Go C, et al. Gender-based discrimination is prevalent in the integrated vascular trainee experience and serves as a predictor of burnout. J Vasc Surg. 2020;71:220–227.43

Mavroudis CL, Landau S, Brooks E, et al. The relationship between surgeon gender and stress during the Covid-19 pandemic. Ann Surg. 2021;273:625–629.44

Khattab MF, Kannan TMA, Morsi A, et al. The short-term impact of COVID-19 pandemic on spine surgeons: a cross-sectional global study. Eur Spine J. 2020;29:1806–1812.45

Shalaby M, Elsheikh AM, Hamed H, et al. Burnout among surgeons before and during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: an international survey. BMC Psychology. 2024;12.46

AlQhtani AZ, Alfaqeeh FA, Alabdulkarim A, et al. Perception of shame in the plastic surgery field. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022;10:e4621.47

Williford ML, Scarlet S, Meyers MO, et al. Multiple-institution comparison of resident and faculty perceptions of burnout and depression during surgical training. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:705–711.48

Khorfan R, Hu YY, Agarwal G, et al. The role of personal accomplishment in general surgery resident well-being. Ann Surg. 2021;274:12–17.49

Mavroudis CL, Landau S, Brooks E, et al. Exploring the experience of the surgical workforce during the Covid-19 pandemic. Ann Surg. 2021;273:e91–e96. doi:10.1097/sla.000000000000469050

Teymoori E, Zareiyan A, Babajani-Vafsi S, et al. Viewpoint of operating room nurses about factors associated with the occupational burnout: a qualitative study. Front Psychol. 2022;13:947189.51

Keyvanara M, Shaarbafchizadeh N, Alimoradnori M Effective factors on occupational burnout among the operating room staff in teaching hospitals affiliated with Isfahan Medical University: a qualitative content analysis. Evidence Based Health Policy, Management and Economics. 2019.52

Yang G, Pan L-Y, Fu X-L, et al. Burnout and job stress of anesthesiologists in the tertiary class A hospitals in Northwest China: a cross-sectional design. Frontiers in Medicine. 2023;10.53

Velando-Soriano A, Pradas-Hernández L, Membrive-Jiménez MJ, et al. Burnout and personality factors among surgical area nurses: a cross sectional multicentre study. Frontiers in Public Health. 2024;12.54

Fagerdahl AM, Torbjörnsson E, Gustavsson M, et al. Moral distress among operating room personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. J Surg Res. 2022;273:110–118.55

D'Souza K, Huynh C, Cadili J, et al. Psychological and workplace-related effects of providing surgical care during the COVID-19 pandemic in British Columbia, Canada. Can J Surg. 2021;64.56

Chen Y-H, Saffari M, Lin C-Y, et al. Burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic among nurses in Taiwan: the parental role effect on burnout. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024;24.57

Destrieux L, Yemmas Y, Williams S, et al. Work environment differences between outpatient and inpatient surgery: a pilot study on the vascular surgeons' perceptions. Ann Vasc Surg. 2024;104:156–165.58

Idrees S, Sabaretnam M, Chand G, et al. Noise level and surgeon stress during thyroidectomy in an endocrine surgery operating room. Head & Neck. 2024;46:37–45.59

Narayanan A, Cavadino A, Fisher JP, et al. The effect of music on the operating surgeon: a pilot randomized crossover trial (the MOSART study). ANZ J Surg. 2024;94:299–308.60

Behzad I, Maryam B Musculoskeletal disorders in operating room: a phenomenological study. J Musculoskelet Res. 2021.61

Jagetia A, Vaitheeswaran K, Mahajan M, et al. Gender differences in perceived stress among neurosurgeons: a cross-sectional study. Neurol India. 2022;70:1377–1383.62

Keyvanara M, Zadeh N, Alimoradnori M Burnout and its related factors among the operating room staff in teaching hospitals affiliated with the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. 2020. doi:10.18502/jebhpme.v4i1.255363

Min L, Chen Y, Fei Y, et al. Noise in the outpatient operating room. Gland surgery. 2020. doi:10.21037/gs.2020.04.0964

Maddineshat M, Hashemi M, Tabatabaeichehr M. Evaluation of the disruptive behaviors among treatment teams and its reflection on the therapy process of patients in the operating room: The impact of personal conflicts. J educ health promot. 2017;6:69.65

Dalen A, Jung J, van Dijkum N, et al. Analyzing and discussing human factors affecting surgical patient safety using innovative technology. J Patient Saf. 2022;18:617–623.66

Lee Y, Koh C, Kang C. Effects of patient safety culture on nurse burnout in the operating room. Stress. 2020;28:11–24.67

Arriaga AF, Sweeney RE, Clapp JT, et al. Failure to debrief after critical events in anesthesia is associated with failures in communication during the event. Anesthesiology. 2019;130:1039–1048.68

Wei J, Yao X, Tian S, et al. Effect of special training method based on breathing meditation training on negative emotions, job burnout and attention in operating room nurses. Altern Ther Health Med. 2024.69

Oh Y, Gill S, Baek D, et al. Improving the mental health of surgical teams through operating room design. Herd. 2024;17:57–76.70

Taribagil P, Liu T, Bhattacharya V, et al. Do we need a co-pilot in the operating theatre? A cross-sectional study on surgeons' perceptions. Scott Med J. 2023;68:166–174.71

Arad D, Finkelstein A, Rozenblum R, et al. Patient safety and staff psychological safety: a mixed methods study on aspects of teamwork in the operating room. Frontiers in Public Health. 2022;10:1060473.72

Orr JW, Thompson AM, Bruens D, et al. Improving operating room efficiency: relocating a surgical oncology program within a health care system. Ochsner J. 2022;22:230–238.73

Kim A, Lee H. Influences of teamwork and job burnout on patient safety management activities among operating room nurses. J Korean Acad Nurs Adm. 2022. doi:10.11111/jkana.2022.28.5.60574

Chenani K, Nodoushan R, Jahangiri M, et al. Quantification of the impact of factors affecting the technical performance of operating room personnel: expert judgment approach. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2022;41:9–16.75

Kamande S, Sarpong K, Murray J, et al. Turnover time between elective operative cases: does the witching hour exist for the operating room? World J Surg. 2022;46:2939–294576

Athanasiadis D, Monfared S, Whiteside J, et al. What delays your case start? Exploring operating room inefficiencies. Surg Endosc. 2020;35:2709–2714.77

Kacem I, Kahloul M, El Arem S, et al. Effects of music therapy on occupational stress and burn-out risk of operating room staff. Libyan J Med. 2020;15:1768024.78

Silver D, Kaye AD, Slakey D. Surgical flow disruptions, a pilot survey with significant clinical outcome implications. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2020;24.79

Katafigiotis I, Sabler IM, Heifetz EM, et al. Factors predicting operating room time in ureteroscopy and ureterorenoscopy. Curr Urol. 2019;12:195–200.80

Kougias P, Tiwari V, Sharath SE, et al. A statistical model-driven surgical case scheduling system improves multiple measures of operative suite efficiency: findings from a single-center, randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2019;270:1000â–11004.81

Lindemann J, Dageforde LA, Brockmeier D, et al. Organ procurement center allows for daytime liver transplantation with less resource utilization: May address burnout, pipeline, and safety for field of transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:1296–1304.82

Rangasamy V, Thampi Susheela A, Mueller A, et al. The effect of a one-time 15-minute guided meditation (Isha Kriya) on stress and mood disturbances among operating room professionals: a prospective interventional pilot study. F1000Res. 2019;8:335.83

Park SY, Cheong HS, Kwon KT, et al. Guidelines for infection control and burnout prevention in healthcare workers responding to COVID-19. Infect Chemother. 2023;55:150; 2023-01-01. doi:10.3947/ic.2022.016484

Barreto MDS, Leite A, García-Vivar C, et al. The experience of coronaphobia among health professionals and their family members during COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Collegian. 2022;29:288–295.85

Rice EN, Xu H, Wang Z, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: analysis of the HERO Registry. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0293392.86

Deltour V, Poujol A-L, Laurent A. Post-traumatic stress disorder among ICU healthcare professionals before and after the Covid-19 health crisis: a narrative review. Ann Intensive Care. 2023;13:66.87

Kelsey EA, West CP, Fischer KM, et al. Well-being in the workplace: a book club among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Prim Care Community Health. 2023;14:21501319231161441.88

Razai MS, Kooner P, Majeed A. Strategies and interventions to improve healthcare professionals’ well-being and reduce burnout. J Prim Care Community Health. 2023;14:215013192311786.89

Babapour A-R, Gahassab-Mozaffari N, Fathnezhad-Kazemi A. Nurses’ job stress and its impact on quality of life and caring behaviors: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nursing. 2022;21:75.90

Etherington C, Boet S. Why gender matters in the operating room: recommendations for a research agenda. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121:997–999.91

Ujjan BU, Hussain F, Nathani KR, et al. Factors associated with risk of burnout in neurosurgeons: current status and risk factors. Acta Neurologica Belgica. 2022;122:1163–1168.92

Carmassi C, Foghi C, Dell'Oste V, et al. PTSD symptoms in healthcare workers facing the three coronavirus outbreaks: what can we expect after the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292:113312.93

Gold KJ, Kuznia AL, Laurie AR, et al. Gender differences in stress and burnout: department survey of academic family physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:1811–1813. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06287-y94

Rabatin J, Williams E, Baier Manwell L, et al. Predictors and outcomes of burnout in primary care physicians. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7:41–43.95

Rakestraw SL, Chen H, Corey B, et al. Closing the gap: increasing female representation in surgical leadership. Am J Surg. 2022;223:273–275.96

Kim Y, Pendleton AA, Boitano LT, et al. The changing demographics of surgical trainees in general and vascular surgery: national trends over the past decade. J Surg Educ. 2021;78:2117–2126.97

Al-Suraihi WA, Samikon SA, Al-Suraihi A-HA, et al. Employee Turnover: Causes, Importance and Retention Strategies. Eur J Bus Manag Res. 2021;6:1–10.98

Rodziewicz TL, Houseman B, Vaqar S, et al. Medical Error Reduction and Prevention. [Updated 2024 Feb 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499956/99

Al-Ghunaim TA, Johnson J, Biyani CS, et al. Surgeon burnout, impact on patient safety and professionalism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Surg. 2022;224(1, part A):228–238.100

Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:1317–1331.101

Douglas RN, Stephens LS, Posner KL, et al. Communication failures contributing to patient injury in anaesthesia malpractice claims✰. Br J Anaesth. 2021;127:470–478.102

Skråmm SH, Smith Jacobsen IL, Hanssen I. Communication as a non-technical skill in the operating room: A qualitative study. Nurs Open. 2021;8:1822–1828.103

Neriman A. Effective communication in operating room and patient safety. J Health Res. 2018;4:183; 2018-12-07.104

Önler E, Yildiz T, Bahar S. Evaluation of the communication skills of operating room staff. J Interprof Educ Pract. 2018;10:44–46.105

Imani B, Jalal SB. Explaining The Impact of Surgical Team Communication Skills On Patient Safety In The Operating Room: A Qualitative Study. Research Square Platform LLC; 2021.106

Moscelli G, Mello M, Sayli M, et al. Nurse and doctor turnover and patient outcomes in NHS acute trusts in England: retrospective longitudinal study. BMJ. 2024;387:e079987; 2024-11-20.107

Sillero A, Zabalegui A. Organizational factors and burnout of perioperative nurses. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2018;14:132–142.108

Weiss A, Elixhauser A, Andrews R. Characteristics of Operating Room Procedures in US Hospitals, 2011. Statistical brief #170: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014.109

Friedman DM, Sokal SM, Chang Y, et al. Increasing operating room efficiency through parallel processing. Ann Surg. 2006;243:10–14.110

Chasseigne V, Leguelinel-Blache G, Nguyen TL, et al. Assessing the costs of disposable and reusable supplies wasted during surgeries. Int J Surg. 2018;53:18–23.111

Nelson J A Silent Struggle: Medscape Nurse Practitioner Burnout & Depression Report 2024. 2024. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2024-np-burnout-rpt-6017518?reg=1#12112

Mölnlycke. Procedure pack. [Internet]. 2024. Accessed August 14, 2024. https://www.molnlycke.com/products-solutions/ProcedurePak-trays/113

Rovira-Simón J, Sales-i-Coll M, Pozo-Rosich P, et al. Surgical block 4.0: a digital intervention based on a real-time location patient-flow solution to support the automation of surgical pathways. Future Healthc J. 2022;9:194.114

Huang Y, Yajuan K, Hongying Z, et al. Hidden dangers and preventive measures in the inventory of articles in operating room. Open J Prev Med. 2021;11:192–198.115

Janki S, Mulder EEAP, Ijzermans JNM, et al. Ergonomics in the operating room. Surg Endos. 2017;31:2457–2466.116

Damiani S, Bendinelli M, Romagnoli S. Intensive care and anesthesiology. Donaldson L, Ricciardi W, Sheridan S, Tartaglia R, eds. Textbook of Patient Safety and Clinical Risk Management. Springer Copyright 2021, The Author(s); 2021:161–175.117

Robertson JM, Dias RD, Yule S, et al. Operating room team training with simulation: a systematic review. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2017;27:475–480. doi:10.1089/lap.2017.0043118

Escher C, Rystedt H, Creutzfeldt J, et al. All professions can benefit—a mixed-methods study on simulation-based teamwork training for operating room teams. Advances in Simulation. 2023;8.119

Pati AB, Mishra TS, Chappity P, et al. Use of technology to improve the adherence to surgical safety checklists in the operating room. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2023;49:572–576. doi:10.1016/j.jcjq.2023.04.005120

Koninckx PR, Stepanian A, Adamyan L, et al. The digital operating room and the surgeon. Gynecological Surgery. 2013;10:57–62; 2013-02-01.121

Campbell K, Gardner A, Scott DJ, et al. Interprofessional staff perspectives on the adoption of or black box technology and simulations to improve patient safety: a multi-methods survey. Advances in Simulation. 2023;8.122

Cheikh Youssef S, Haram K, Noël J, et al. Evolution of the digital operating room: the place of video technology in surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2023;408.123

Fond G, Lucas G, Boyer L. Health-promoting work schedules among nurses and nurse assistants in France: results from nationwide AMADEUS survey. BMC Nurs. 2023;22:255.124

Hughes TM, Collins RA, Cunningham CE. Depression and suicide among American surgeons—a Grave threat to the surgeon workforce. JAMA Surg. 2023;159:7–8.125

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health’s Impact Wellbeing™ Campaign Releases Hospital-Tested Guide to Improve Healthcare Worker Burnout. 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2024/p0318-Worker-Burnout.html