Total Parenteral Nutrition, An Ally in the Management of Patients With Intestinal Failure and Malnutrition

A Long-Term View

- Spencer, Carolyn T. RD, CNSD

- Compher, Charlene W. PhD, RD, FADA, CNSD

ABSTRACT.

The Influence of Hypoproteinemia on the Formation of Callus in Experimental Fracture. Jonathan E. Rhoads, William Kasinskas. Surgery 11:38-44, 1942

Background:

This abstract relates the importance of adequate serum protein levels for proper bone healing. The process in which the dog's ulna was sawed, whereby the radius acted as a natural splint, was clever and compassionate. This study and its findings help support the idea that adequate serum protein levels and nutritional status impact sound surgical practices and outcomes. Hypoproteinemia has been shown to delay healing in soft tissue wounds in dogs and is frequently present in patients with wound disruption. These observations suggest that hypoproteinemia may also play a role in the delay of fracture healing, and their purpose was to determine the effect of hypoproteinemia on the formation of bony callus after fractures in dogs.

Methods:

Normal appearing, medium-sized mongrel dogs were used. Hypoproteinemia was induced by a low-protein diet and repeated plasmapheresis. The diet was adequate for all of the dog's requirements except protein, which was approximately 1%. Plasmapheresis consisted of aspirating blood from the femoral artery, whereby the plasma was removed and the remaining diluted cells were returned to the animal from which they were taken. This procedure was completed about 3 times per week until the serum protein level declined to below 4 g/dL and then as needed to maintain that level for a period of 6 weeks after fracture. During the control periods, the diet consisted of table scraps. The 3 stock dogs subsisting on this diet maintained plasma protein levels of 6 to 7 g/dL. The type of fracture induced for the study was Gigli saw section of the ulna, which permits self-splinting by the radius and allows readily accessible x-ray examination. In the spring of 1938, 3 dogs were rendered hypoproteinemic, with plasma protein levels near 4 g/dL, and the left ulna of each animal was sectioned about 5 cm above the distal end. The hypoproteinemic regimen was ended after a 6-week period after fracture. One of the dogs died during the summer, but the other 2 recovered completely and were used as controls the following year.

Results:

X-ray of callus formation at 40 to 45 days in the hypoproteinemic dogs is less evident when compared with the normal dogs at about the same interval. A later comparison of callus formation in the hypoproteinemic dogs at 60 to 74 days shows that callus formation is still retarded compared with the normal dogs. Variations in callus formation among hypoproteinemic dogs were attributed to variation in age not realized at the beginning of the experiment. All 6 comparisons reveal that less callus formation occurred when the animals were hypoproteinemic.

Discussion/Conclusions:

Many factors, including the influence of vitamins, especially vitamin D, and calcium metabolism have been studied in connection with fracture healing, but the role of plasma proteins has not yet garnered much attention. Fibroplasia, which plays a role in the first phase of fracture healing, appears to be greatly retarded in the presence of severe hypoproteinemia. Hypoproteinemic alterations in circulation, plasma volume, and serum calcium levels may play a role. It is uncertain by what mechanism the hypoproteinemic state interfered with the formation of bony callus. Hypoproteinemia is an abnormality that does not exist alone but one that is associated with many physiologic alterations. Bones, like all living tissue, need protein for growth. Severe hypoproteinemia retards the formation of bony callus in fractures produced in dogs by section of the ulna with a Gigli saw.

Figure

No caption available.

Abstract by Jung Kim, RD

Clinical Dietitian

Clinical Nutrition Support Service

Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, PA

ABSTRACT.

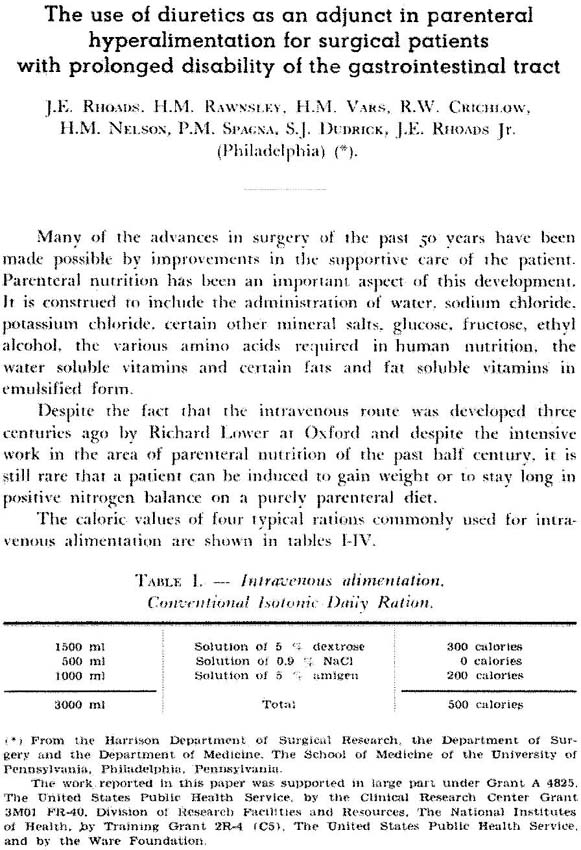

The use of diuretics as an adjunct in parenteral hyperalimentation for surgical patients with prolonged disability of the gastrointestinal tract. Rhoads JE, Rawnsley HM, Vars HM, Crichlow RW, Nelson HM, Spagna PM, Dudrick SJ, Rhoads JE Jr: Bull Int Soc Surg 24:59-70, 1965

In a 2001 interview, Rhoads said, “We were stymied and about to give the whole effort up, when I had the idea that we might use the same diuretics that our medical colleagues were using for the control of hypertension”. The article abstracted below describes another key stepping stone in his and his colleagues' clinical development of parenteral nutrition: using diuretics to allow patients to compensate physiologically for required fluid volume. It provides a glimpse into the problems encountered during the development of early parenteral nutrition. For humans, the peripheral route of IV access and volume intolerance issues limited adequacy of nutrient delivery via hyperalimentation.

In this abstract, Rhoads characteristically recognizes individual contributions of his coauthors in their combined research efforts. Dr. Rhoads' value for and acknowledgment of collaboration was a hallmark of his career and is the grounding force behind research developments in parenteral nutrition to the present day. Background: Among the advances in surgery since 1915, parenteral nutrition is an important contribution to supportive patient care. There continue to be difficulties in achieving weight gain or maintaining positive nitrogen balance on a purely parenteral diet. Limiting factors include the need for large volumes of fluid to deliver needed nutrients via peripheral vein and the caloric value of the solute. Purpose: The purpose of this study is to determine if newly developed diuretics can improve patients' tolerance to the volume and glucose delivery required for parenteral nutrition, thus maintaining electrolyte balance. Study Design: Using diuretics (chlorthiazide, mannitol, and Thiomerin) and various parenteral nutrition regimens (variable in glucose, amino acid, and fluid content), patients' fluid balance, urinary dextrose excretion, nitrogen balance, and electrolyte (sodium, chloride, potassium) balance were measured. In addition, laboratory dogs were used to study nitrogen and electrolyte balance. Results: Sixteen patients received 5000 mL of parenteral nutrition over 24 hours and 500 mg chlorthiazide, with an average urinary output of 4246 mL. One patient, who received 7000 mL over 13 days with 750 mg chlorthiazide over 24 hours, had a urine output of 5813 mL and <1% glucose excretion. Three patients each received different doses of mannitol (25 g, 37.5 g, and 75 g) with fluid balance ranging from −135 mL to +2545 mL. Urinary loss of glucose was not viewed as a significant problem. Glucose loss did not exceed 10% and averaged <4% of that infused when glucose alone was given. When protein hydrolysate and glucose were infused together, the urinary loss of glucose was decreased to approximately 1%. Without the use of diuretics, 2 laboratory dogs tolerated solution volume of 25% of their body weight. Chlorthiazide produced greater electrolyte losses than mannitol. In human studies, weight gain was greatest with mannitol, and chlorthiazide demonstrated the greatest level of positive glucose balance (that is, less loss of infused glucose renally). Increased losses of sodium, chloride, and potassium were seen with all diuretics used; however, repletion was not difficult. Chlorthiazide produced a higher level of nitrogen balance (+6 g) than did mannitol or Thiomerin. Discussion/Conclusion: The use of diuretics in proper dosage permits the physician to increase the volume of fluid used to deliver parenteral nutrition from 3 to 5 or even 7 L (with proportionate increase in nutrients delivered) without producing a “water overload.” Electrolyte balance can be maintained through additional provision of electrolytes. Furthermore, this program enables the achievement of positive nitrogen balance in humans.

Abstract by Amanda Wasylik, RD

Clinical Dietitian

Clinical Nutrition Support Service

Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, PA