Introduction

Since the public availability of internet in 1995, India has witnessed a continuous growth in technology. In India alone, internet use has grown from 5 million users in 2004 to 687.6 million in 2020. The number of internet users in India increased by 128 million (+23%) between 2019 and 2020. While its positive aspects are well-known, concern continues to mount regarding problematic internet users (PIU). Internet is an essential media for personal communication, academic research, and information exchange, but it still carries its own hazards such as internet addiction and online pornography.

Internet has become one of the main sources of pornography use, as it is easily available, affordable, and accessible. It has become much easier to create, upload, and share pornographic content. Majority of the people who use internet to complement their offline sexuality are healthy, and it even enhances and enriches their sexual life. However, Cooper et al. estimated that 20% of the people who use the internet for pornography and other sexual purposes may experience long-lasting devastating consequences and may find themselves unable to physically withdraw from the internet. For several hours of the day, they may engage in compulsive viewing and collecting of pornographic images and videos, seeking sexual intimacy and romance online. It has also been argued by certain authors that cybersex has the highest potential for developing into an addiction.

Excessive use of pornography is associated with psychological distress, inter-personal isolation, family problems, vocational problems, and legal consequences. Internet pornography use is not always problematic. Controlled and limited use may have some positive consequences also, such as greater openness to experience and less sexual guilt. According to some authors, internet pornographic use in excess of 11 h per week is defined as problematic pornography internet use. However, some people do consider their use as problematic for relational, vocational, moral, or religious reasons.

Medical students usually spend long hours on the internet for getting the latest updates on medical education and research, using emails, social media, discussion forums, online games, and watching movies online.,10 Considering the significant stress associated with their long working hours, competition amongst students, arduous studies, and living alone away from the home, they are prone to browsing pornographic sites and may indulge in pornography to ameliorate their stress., It may also start or progress out of curiosity, association with peers who view porn, sexual arousal, having a general feeling of excitement and anticipation, for instructional purposes, and to alleviate boredom. Problematic use of internet pornography may affect the overall psychological well-being, academic performance, and the interpersonal relationships of a student. With this background in mind, the present study was conducted to estimate the extent and impact of internet pornography use among undergraduate and postgraduate medical students in a medical college of North India.

Materials and Methods

The present study was conducted in a government medical college located in North India (Haryana state). Institutional ethical clearance was taken before starting the project. Written informed consent was taken, and participants were guaranteed complete anonymity and confidentiality.

It was a cross-sectional, questionnaire-based study where all the students pursuing undergraduate (including internship students) and postgraduate courses were approached for inclusion. We followed random sampling method for selecting the consenting participants. All students who were above 18 years of age and willing to give written informed consent were included in the study. The exclusion criteria were students less than 18 years of age, suffering from any serious physical illness or mental health condition (which could affect quality of life and general well-being), and not consenting for inclusion. The data was collected using a predesigned semi-structured sociodemographic questionnaire. A total of 725 students were interviewed, out of which 393 students agreed on using internet for pornography.

Any medical student out of the total sample who used cyber-pornography (sexually explicit photographs and videos), sex chat, and sex via web camera was further assessed in detail, using different scales to evaluate the extent and impact of pornographic use. A total of 393 students were selected for the study. The extent of their internet use was assessed through the Internet Addiction Test (IAT), which consists of 20 items. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 5 with a maximum score of 100. Scores of 0 to 30 points reflect a normal level of internet usage; 31 to 49 indicate the presence of a mild level of internet addiction; 50 to 79 reflect the presence of a moderate level; and 80 to 100 indicate a severe dependence upon the internet. Using the IAT, the students were classified as having problematic (moderate/severe) or nonproblematic pornographic use (mild). They were separately asked to specify the time spent on pornography use per week.

Specific question clusters in IAT represent the impact on different domains of functioning. Questions 3 and 4 reflect neglect of social life. High ratings for neglect of social life items indicate that the respondent most likely utilizes online relationships to cope with situational problems and/or to reduce mental tension and stress, frequently forms new relationships with fellow online users, and uses the internet to establish social connections that may be missing in his or her life. Questions 6, 8, and 9 reflect neglect of work. High ratings for neglect-of-work-related exam items indicate that the respondent may view the internet as a necessary appliance akin to the television, microwave, or telephone. Job or school performance and productivity are most likely compromised because of the amount of time spent online, and the respondent may become defensive or secretive about the time spent online. The psychometric properties of the IAT show that it is a reliable and valid measure that has been used in further research on internet addiction.

General well-being and impact of pornographic use was assessed by the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)-30 and the WHO Quality of Life Index (WHOQOL)-BREF scale. The GHQ is a validated scale which measures current mental health and has been used extensively in different settings and cultures. The questionnaire was originally developed as a 60-item instrument but at present a range of shortened versions of the questionnaire are available. GHQ-30 is a 30-item scale which uses a 4-point scale (from 0 to 3). The scoring ranges from 0 to 90. The scale asks whether the respondent has experienced a particular symptom or behavior recently, with higher scores indicating worse outcomes.

The WHOQOL-BREF is a validated scale which was developed from the WHOQOL-100. Like the WHOQOL-100, it consists of 24 facets grouped into four domains related to quality of life (physical health, psychological, social relationships, and environment), as well as one facet on overall quality of life and general health. One item from each facet, which best explains a large portion of the variance, was selected for inclusion in the WHOQOL-BREF. Two items were selected from the overall quality of life facet for a total of 26 items. Potential scores for all domain range from 0 to 100. Domains scores are scaled in a positive direction (ie, higher scores denote higher quality of life).

The collected data was tabulated, and statistical analysis was done using the SPSS software version 20 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20. IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Frequencies and percentages were computed for the categorical variables, and their significance in relation to IAT scores was computed using chi-square test and independent t-test. Mean and standard deviation were calculated for the continuous variables, and correlation between the variables was assessed by means of the Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

Results

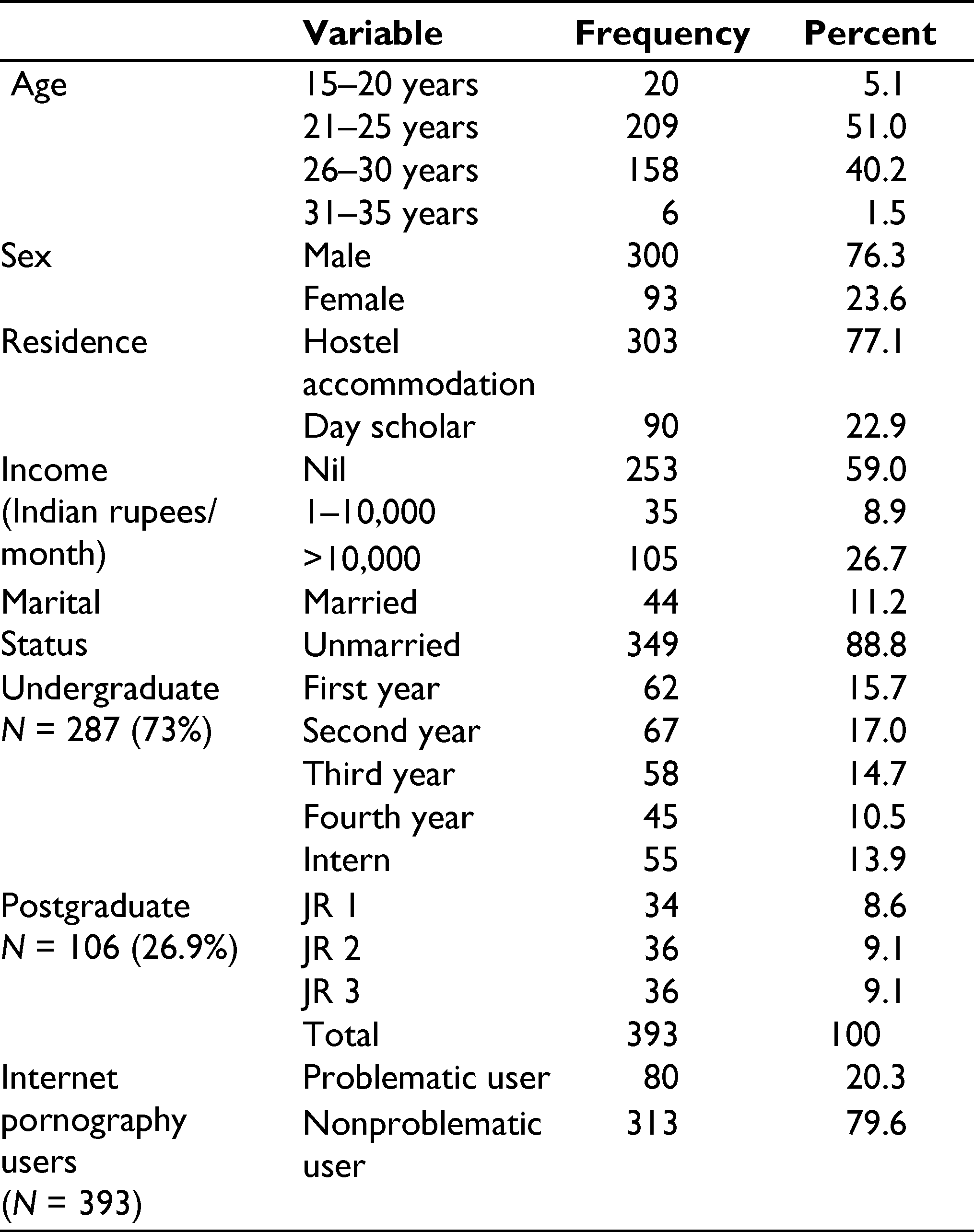

In the present study, a total of 725 (416 males and 309 females) undergraduate and postgraduate medical students who were internet users were asked if they were viewing online pornography or not. Out of these, 393 students (300 males and 93 females) were using sexually explicit material online and were assessed further in detail. As shown in Table 1, majority of these 393 students were 21 years to 25 years (51%) of age and males (76.3%). Around 88% of the students were unmarried and 60% were dependent on their parents regarding their expenses. Around 73% of the subjects were undergraduates.

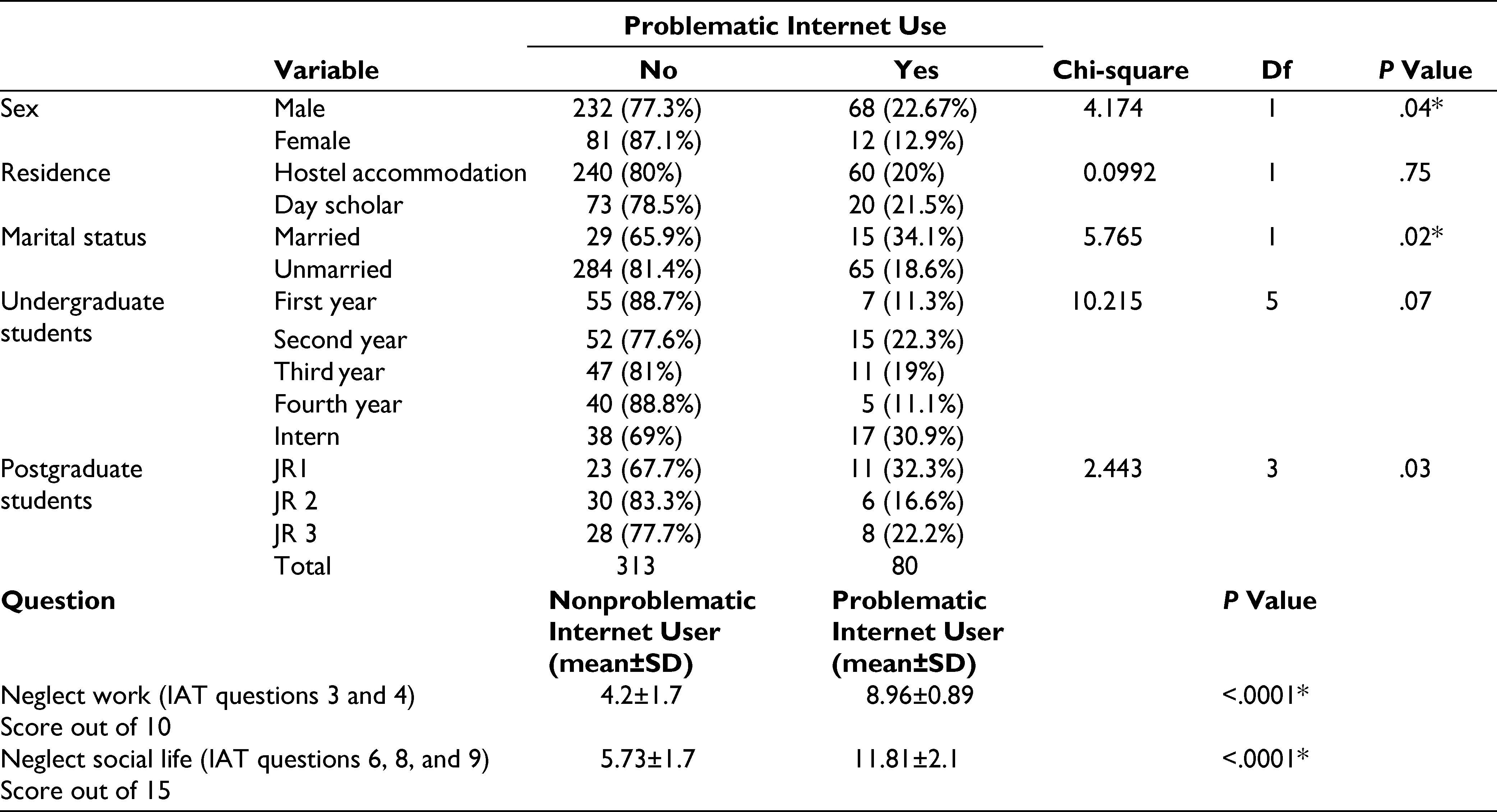

Table 2 shows that among all the students who had access to various pornographic content, 80 students were found to be problematic internet users. The number of males (68) in this category were more as compared to females, and this difference was seen to be statistically significant (P value = .04). Around 18% of unmarried and 34% of married students were problematic internet users and it was seen that unmarried students were significantly (P value = .016) more in number as compared to married students. Out of 287 undergraduate students, 55 (19.16%) students were found to be problematic internet users (PIUs, and second year undergraduate students and interns were found to be more problematic as compared to others. Around 23.5% of the postgraduate’s students were PIU, and a majority of them were in their first year of the postgraduate program. The undergraduate and postgraduate students did not differ significantly within the respective groups in regard to PIU. Neglect of work and social life was observed to be more in problematic internet users than nonproblematic internet users.

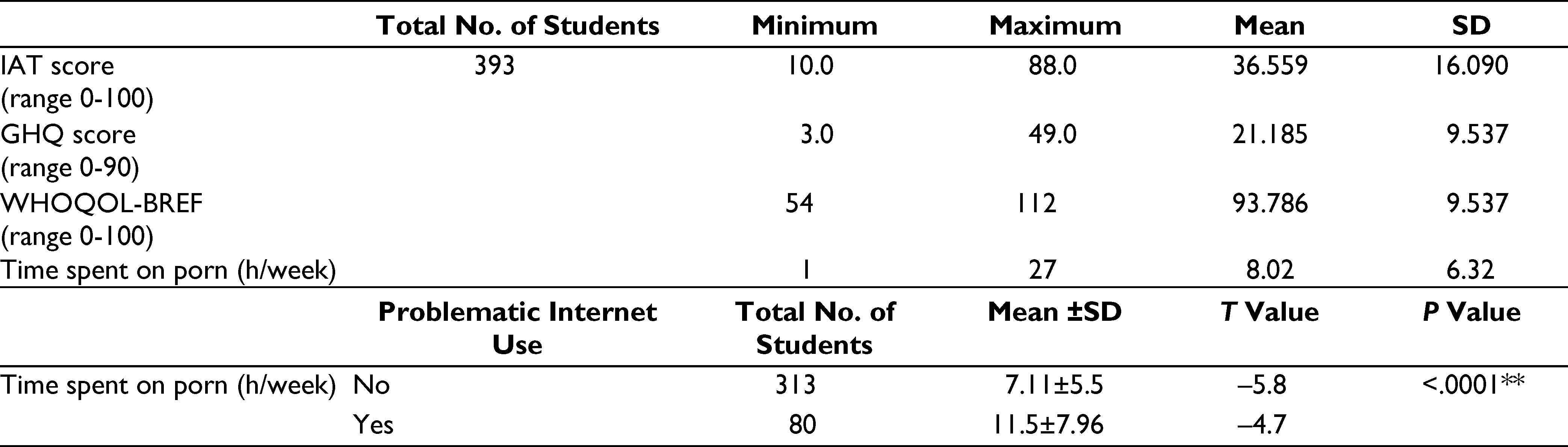

Table 3 highlights that the average score of IAT was 36.55±16.09. The mean GHQ score and WHOQOL-BREF were 21.18±9.53 and 93.78±9.53, respectively. PIU was seen in 20.5% (80/393) of the participants. Students using pornographic content were spending a mean time of 8.02±6.32 h/week on pornography. Time spent on online pornography by problematic users (11.5±7.96 h/week) was significantly more than those participants who were viewing internet pornography without any problems (7.11±5.5 h/week).

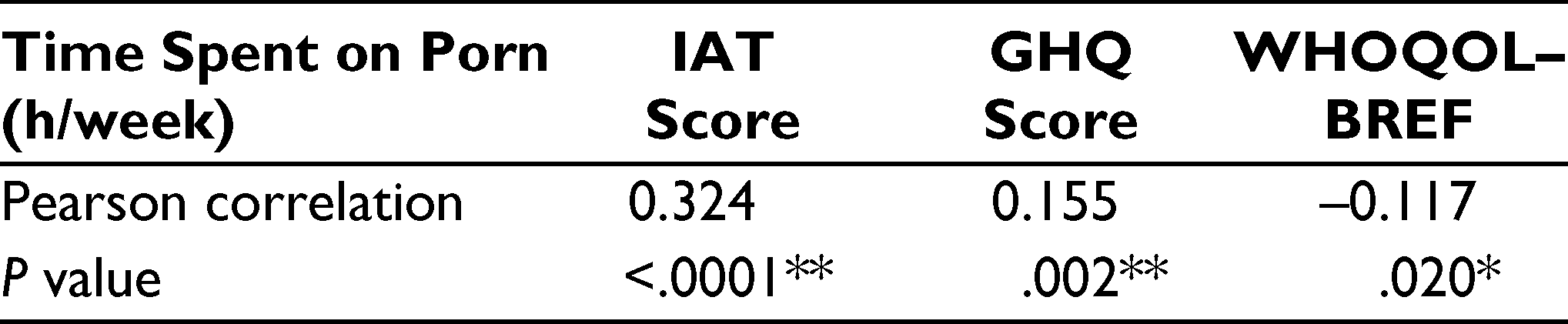

The time spent on pornography was positively correlated with IAT and GHQ scores (Table 4), and it is seen to be highly significant (P value = .000 & .002, respectively). The duration of pornography use is negatively correlated with WHOQOL-BREF scores and was also found to be statistically significant (P value = .02).

Discussion

The study was conducted to estimate the extent and impact of internet pornography use among undergraduate and postgraduate medical students in a government medical college in North India. In the present study, around 3/4 of the students were male and residents of hostels.

We found that a significant proportion of students had at least mild levels of internet pornography use (393 out of 725, 54.2%), out of which around 11% of the total students (80) had problematic internet use, which is similar to studies by Kumar et al and Dwulit et al where around 12% of the students were found to be problematic internet users,; however, 22% were found to be high risk in study conducted in Telangana. Male participants had higher prevalence of problematic internet use as compared to females, which is line with others studies., We also found that people who had greater internet addiction would indulge more in pornography. As the time spent on internet for use of pornography increases, the general measures of health and well-being decline.

The present study shows that inclination toward pornographic content was more in males as compared to females. Our results are similar and were in agreement with other studies which have suggested different reasons for this gender difference. The attitude and behavior of males and females is quite different regarding sexually explicit material. It has been observed that males go online at an earlier age to view sexually explicit materials and are more likely to view online pornography in comparison to females., They find pornographic and sexually explicit material to be more arousing and erotic than females, who often found it to be disgusting and disturbing, although some do find it to be amusing. Females often negatively compare themselves with internet pornographic material and have reported feeling of anger toward it, and they use internet pornography only in response to a request by their male partner. Also, females may have been more reluctant to admit pornography use.

In the present study, problematic internet use was significantly more common among married students (than among unmarried medical students) who were viewing online pornography. This is in contrast to the study conducted by Cooper et al, who found that heavy cybersex users who spend more than 11 h on the internet for sexual purposes weekly were more likely to be partnered or married, and who reported greater subjectively perceived interference of cybersex in their lives. However, a study in Egypt suggests that married men watch porn for sexual gratification. Further research is warranted with respect to marital differences in pornography use.

In this study, we found that problematic internet users spent significantly more time on online pornography (11.5±7.96 h/week) than those participants who were viewing internet pornography with mild addiction (7.11±5.5 h/week). The study also found that those who spend more time on online pornography neglect their social life, utilize online relationships to cope with stress and have unstable relationships, and neglect their work leading to a decrease performance and productivity, which are most likely compromised because of the amount of time spent online. This is in accordance with Cooper’s view on problematic internet use for sexual gratification and seems logical as a high level of use is more likely to create problems in their social, occupational, and personal life. However, others believe that time spent on internet pornography is not an important determinant of its perception as being problematic.,

In the present study, time spent on internet pornography shows positive correlation with GHQ-30 and IAT scores and negative correlation with WHOQOL-BREF scores, suggesting that greater time spent on online pornography predicts decline quality of life and general health measures. A previous study found that more than half of male internet pornography users felt that their pornography use is problematic in at least one major life domain, with the greatest implications in psychological/spiritual, behavioral (eg, relationship problems and problems at work or school), and social domains.

This was probably among the very few studies conducted on Indian medical students to assess the impact of pornography on their quality of life and general health measures. Medical students are the future and backbone of the Indian healthcare infrastructure, and hence their psychological health and quality of life is of paramount importance. The strengths of the study lie in the good sample size, inclusion of both undergraduate and postgraduate students, and its assessment of impact of pornography on general health and quality of life. The limitations include the relatively small female population, generalizability issue, possibility of recall bias, stigma and hesitation about a sensitive topic preventing appropriate disclosure and responses from participants, single medical college, and limited sample size cross sectional assessment. As there is no separate questionnaire to assess the problematic pornographic use, the IAT scores were used which positively correlated with the time spent on pornography, which is a limitation for this study.

Conclusion

The internet has become an integral part of our life, and internet pornography is one of the key elements which leads users toward internet addiction. Medical students are the future of healthcare in India, and a significant proportion of them are problematic pornographic users. As IAT scores positively correlated with the time spent on pornography the study assumed that pornography use significantly attributed to IAT scores. As the time spent on internet for use of pornography increases, the general measures of health and well-being decline, which may ultimately affect their education and self-confidence. However, the opposite can also correct as those who have poorer general quality of life and academic performance resort to internet porn usage to alleviate distress and fill up their time. The problem calls for immediate necessary interventions such as targeted counselling and education. Preventive measures like compulsory sex education during high school (during the formative years of an adolescent), and active measures by the government through restriction of pornographic sites which host illegal and harmful aggressive content from the internet is the need of the hour. Better coping strategies and stress management can be used as a tool to mitigate this issue.

Ethics Approval Statement The study has been approved by Institutional Ethical Committee. The study have been performed in accordance with ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Kemp S. Digital 2020: India. DataReportal–Global Digital Insights; 2020. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-india

- 2. Hald GM, Kuyper L, Adam PCG, . Does viewing explain doing? Assessing the association between sexually explicit materials use and sexual behaviors in a large sample of Dutch adolescents and young adults. J Sex Med. 2013;10:2986–2995.

- 3. Cooper A, Delmonico DL, Burg R. Cybersex users, abusers, and compulsives: New findings and implications. J Treat Prev. 2000;7(1-2):5–30.

- 4. Goodson P, McCormick D, Evans A. Searching for sexually explicit materials on the Internet: an exploratory study of college students’ behavior and attitudes. Arch Sex Behav. 2001;30:101–118.

- 5. Short MB, Black L, Smith AH, . A review of Internet pornography use research: methodology and content from the past 10 years. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2012;15:13–23.

- 6. Grubbs JB, Volk F, Exline JJ, . Internet pornography use: Perceived addiction, psychological distress, and the validation of a brief measure. J Sex Marital Ther. 2015;41(1):83–106.

- 7. Weinberg M, Williams C, Kleiner S, . Pornography, normalization, and empowerment. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39:1389–1401.

- 8. Levin ME, Lillis J, Hayes SC. When is online pornography viewing problematic among college males? Examining the moderating role of experiential avoidance. Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2012;19:168–180.

- 9. Subhaprada CS, Kalyani P. A cross-sectional study on internet addiction among medical students. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2017 ;4(3):670–674.

- 10. Anand N, Thomas C, Jain PA, . Internet use behaviors, internet addiction and psychological distress among medical college students: a multi centre study from South India. Asian J Psychiatry. 2018 ;37:71–77.

- 11. Garg K, Agarwal M, Dalal PK. Stress among medical students: a cross-sectional study from a North Indian Medical University. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017 ;59(4):502.

- 12. Laier C, Brand M. Mood changes after watching pornography on the Internet are linked to tendencies towards Internet-pornography-viewing disorder. Addict Behav Rep. 2017 ;5:9–13.

- 13. Goodson P, McCormick D, Evans A. Sex on the Internet: college students’ emotional arousal when viewing sexually explicit materials on-line. J Sex Educ Ther. 2000 ;25(4):252–260.

- 14. Young KS. Internet addiction: the emergence of a new clinical disorder. Cyber Psychol Behav. 1998;1:237–244.

- 15. Keser H, Eşgi N, Kocadağ T, . Validity and reliability study of the Internet addiction test. Mevlana Int J Educ. 2013 ;3(4):207–222.

- 16. Goldberg DP. Manual of the General Health Questionnaire. NFER Publishing; 1978.

- 17. WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551–558.

- 18. Tait RJ, Hulse GK, Robertson SI. A review of the validity of the General Health Questionnaire in adolescent populations. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2002 ;36(4):550–557.

- 19. Agnihotri K, Awasthi S, Chandra H, . Validation of WHO QOL-BREF instrument in Indian adolescents. Indian J Pediatr. 2010 ;77(4):381–386.

- 20. Kumar P, Patel VK, Bhatt RB, . Prevalence of problematic pornography use and attitude toward pornography among the undergraduate medical students. J Psychosexual Health. 2021;3(1):29–36.

- 21. Dwulit AD, Rzymski P. Prevalence, patterns and self-perceived effects of pornography consumption in Polish University students: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(10):1861.

- 22. Praveera KH, Anudeep M, Junapudi SS. Cyber-pornography addiction among medical students of Telangana. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2021 ;12(1):303.

- 23. Chowdhury MdRHK, Chowdhury MRK, Kabir R, . Does the addiction in online pornography affect the behavioral pattern of undergrad private university students in Bangladesh? Int J Health Sci (Qassim). 2018;12(3):67–74.

- 24. Kvalem IL, Træen B, Lewin B, . Self-perceived effects of Internet pornography use, genital appearance satisfaction, and sexual self-esteem among young Scandinavian adults. Cyberpsychology. 2014 ;8(4):Article 4.

- 25. Twohig MP, Crosby JM, Cox JM. Viewing Internet pornography: For whom is it problematic, how, and why? Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2009;16:253–266.

- 26. Delmonico D, Miller J. The Internet sex screening test: a comparison of sexual compulsives versus non-sexual compulsives. J Sex Marital Ther. 2003;18(3):26176.

- 27. Boies SC. University students’ uses of and reactions to online sexual information and entertainment: links to online and offline sexual behavior. Can J Hum Sex. 2002;11:77–89.

- 28. Johansson T, Hammar’en N. Hegemonic masculinity and pornography: young people’s attitudes toward and relations to pornography. J Mens Stud. 2007;15:57–70.

- 29. Nosko A, Wood E, Desmarais S. Unsolicited online sexual material: what affects our attitudes and likelihood to search more? Can J Hum Sex. 2007;16:1–10.

- 30. Cooper A, Putnam DE, Planchon LA, . Online sexual compulsivity: getting tangled in the net. Sex Addict Compulsivity. 1999;6:79–104.

- 31. Gaber MA, Khaled HN, Nassar MM. Effect of pornography on married couples. Menoufia Med J. 2019 ;32(3):1025.

- 32. Nelson LJ, Padilla-Walker L, Carroll JS. “I believe it is wrong but I still do it”: a comparison of religious young men who do versus do not use pornography. Psychol Relig Spirituality. 2010;2:136–147.

- 33. Patterson R, Price J. Pornography, religion, and the happiness gap: does pornography impact the actively religious differently? J Sci Study Relig. 2012;51:79–89.