Introduction

Infertility has always been a health concern since times immemorial. However, in the post-modern times, it has acquired a monstrous proportion, which warrants a sense of purpose and immediacy. Childlessness is a global problem and is costing both the infertility service providers and the clients dearly not only in terms of time but also money and patience. Barrenness in India is estimated around 2.5%. It is around 5.5% for 30 to 49 age group and 5.2% for 45 to 49 age group.

It is noteworthy that West Bengal has the highest prevalence (14.8%) of infertility amongst women. It was found in a study of West Bengal that maximum number of infertile women (56.54%) were in the age group of 25 to 34 years. In the states like Bihar, Goa, Haryana, Chhattisgarh, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh, infertility prevalence was found to be well above 10%. It is interesting to note that the rate of infertility is quite high among urban women vis-a-vis rural womenfolk.

Emotions and existential nemeses like disillusionment, apathy, despair, guilt, shame, self-blame, anger, discomfiture, and self-reproach are exceedingly common reactive outpourings seen in infertile couples.

Many couples take recourse to dysfunctional coping styles and maladaptive behavior in order to come to terms with the stressful existence once they are aware of their state of infertility. These coping strategies, instead of alleviating their anguish, ironically, heighten the ongoing perturbed state, thus making their mental life and interrelationships much more complex and intricate, which they find extremely difficult to deal with. Hence, it is crucial to include both the couple in the web of intervention and strategize the treatment procedure to lessen their emotional burden.

Infertility is neither an urban phenomenon nor is it confined only to women. Studies have shown that in nearly 30% of all infertility cases, the cause can be attributed to a problem in the man. However, in India, male infertility is largely an ignored phenomenon and women are subjected to a lot of social stigma for being unable to bear children. The need of the hour is, therefore, to give equal importance to male infertility and create awareness about the condition.

Emotions like disappointment, guilt, shame, self-blame, anger, bitterness, discomfort, and resentment are very common reaction patterns observed in infertile couples.

Many couples employ certain maladaptive coping methods as forms of tackling the life—changing demands and apprehensions related to the state of infertility. Such coping styles rather than mitigating the anxiety state, paradoxically, escalate the tensions further.

It is imperative that both the husband and wife are included in the entire treatment process. If both the partners are brought in the gambit of the treatment, it is much easier to gain the conjoint trust and acquire leverage from the treatment offered to them. Therefore, it is of vital importance that the entire therapy structure is carefully designed and sharply directed to alleviating the despair and anxiety in the infertile couples.

A specific therapy for infertile couples can focus on reflection of individual problems and the family history, the acceptance of the situation, the meaning and impact of infertility, including grief work, work on alternative life and self-concepts for the future, the development of coping strategies and strategies to minimize distress, problem and conflict solving, and/or specific issues such as sexual, marital, and other interpersonal problems.

Fertility treatment is a significant emotional journey, and may have an impact on a couple’s relationships with others. The emotions can be conflicting and intense. Therapy is an opportunity to explore their feelings, coping strategies, options, and relationship issues with partners, family, friends, or colleagues. It can help them to adjust and to look at both the short- and long-term consequences of infertility and treatment.

Earlier studies focused mainly on a single factor, therefore present study aims to examine infertility-related stress experienced by both partners and the differences in their individual impact and to present a baseline profile of specific aspects of their coping strategy: ultimately, to gain more insight into the experiences of infertile couples.

Methods

Design

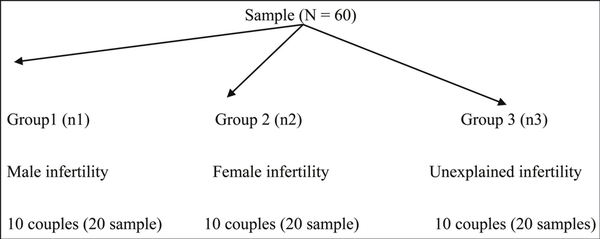

This was a cross-sectional comparative study and followed a purposive sampling method.

Sample

Thirty couples (60 participants) with primary infertility with 20 to 35 years of age and taking treatment at private infertility clinic in a metro city in India for male factor, female factor, and unexplained factor infertility. Male factor infertility group consisted of males with low sperm count, poor sperm functioning, ejaculatory disturbances, and structural abnormalities of the reproductive system. Female factor infertility group consisted of females with polycystic ovarian syndrome, diminished ovarian reserve, abnormalities in the uterus, and blocked fallopian tubes. Unexplained factor infertility group consisted of couples where the cause of infertility was unknown and could not be diagnosed with existing diagnostic tests. Couples who were staying together at least for 3 years were selected. Those couples were not incorporated who had past history of failed in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment, history of any physical disability, other major physical illness, history of substance abuse, psychosis, or significant head trauma. If both the members of the couple (husband and wife) had a known cause for infertility, they were also excluded. Couples between 25 and 40 years, without history of IVF or other mode of treatment and no history of psychoses or substance abuse, were taken. Duration of infertility was taken between 5 and 7 years.

Measures

The following tools were used:

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) was designed as a brief structured interview for the major Axis I psychiatric disorders in DSM-IV and ICD-10. It is a short, structured psychiatric interview which is widely used for psychiatric evaluation and outcome tracking in clinical psychopharmacology trials and epidemiological studies. It has high reliability and validity of 0.70.

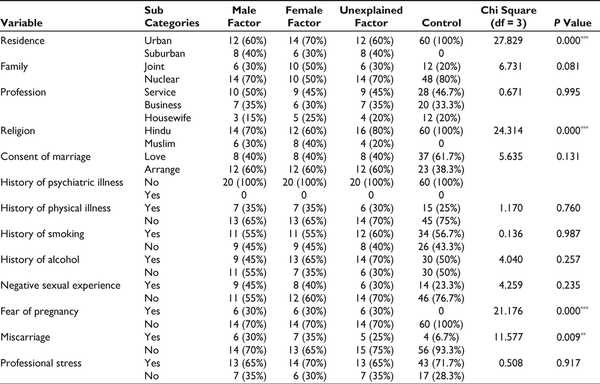

Sample Distribution

Fertility Problem Inventory

The Fertility Problem Inventory was used to measure the level of a couple’s infertility stress. It consists of 46 questions with five scales: social concern (reliability: 0.87), sexual concern (reliability: 0.77), relationship concern (reliability: 0.82), need for parenthood (reliability: 0.84), and rejection of childfree lifestyle (reliability: 0.8). Score indications for females (0-97: low infertility stress), (98-132: average infertility stress), (133-167: moderately high infertility stress), (168 or greater: extremely high amounts of infertility stress). For males (0-87: low infertility stress), (88-113: average infertility stress), (114-146: moderately high infertility stress), and (147 or greater: indicated extremely high amounts of infertility stress).

0.801 is Cronbach’s alphas for each item which indicate a strong reliability.

Ways of Coping Questionnaire

The Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WAYS) is used to measure the coping process. There are 66 items and they can be completed in about 10 minutes. The WAYS is excellent for research on coping and scales include: confrontation coping, distancing, self-controlling, seeking social support, accepting responsibility, escape-avoidance, planful problem solving and positive reappraisal. Internal consistency reliability was found to be 0.78.

Procedure

Informed consent was taken and Axis I disorders were ruled out (substance abuse, psychosis, mood, and anxiety disorders), following which the tools were individually administered in the following order: socio-demographic data sheet, semi-structured clinical data sheet, MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview, Fertility Problem Inventory, and Ways of Coping Questionnaire.

Patients were recruited from BIRTH Infertility Clinic in Kolkata, India. All the patients were diagnosed by a gynecologist and an infertility specialist. All patients recruited had participated in the study. Some couples were apprehensive to give data as they feared loss of privacy. They were assured of the confidentiality and eventually convinced.

Ethics approval was obtained from the research and ethics committees at The Institute of Psychiatry and at The Institute of Post-Graduate Medical Education and Research in June 2015. The study period was between January 2016 and February 2017.

Results

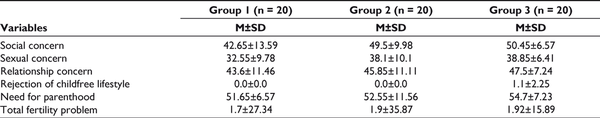

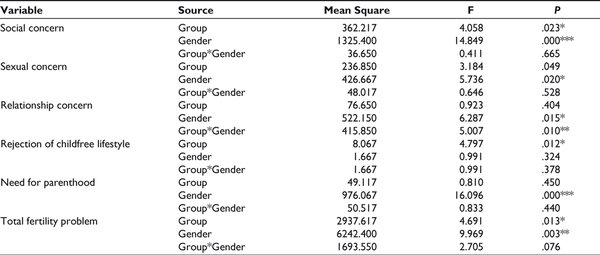

The socio-demographic findings have been given in Table 1. For the variable social concern, significant difference has been found between the groups (male factor, female factor, and unexplained factor) (P <.001) and gender (males and females) (P < .001). Females have scored higher than males in the male factor, female factor, and unexplained factor group in this domain. Female factor group has scored higher than the other groups (Table 2).

Significant difference has been found between the groups (male factor, female factor, and unexplained factor) (P < .001) and gender (males and females) (P < .001) with regard to social concern. Males have scored higher than females in the male factor, female factor, and unexplained factor group in this domain (Table 2).

Females have scored higher than males in the female factor and unexplained factor group, whereas in the male factor group males have scored higher than females. Female factor group has scored higher than the other groups. Significant difference has been found between the gender (males and females) (P < .001) (Table 2).

For the variable rejection of childfree lifestyle, significant difference has been found between the groups (male factor, female factor, and unexplained factor) (P < .001) (Table 2).

Significant difference has been found between the gender (males and females) with respect to need for parenthood (P < .001). Females have scored higher than males in the male factor, female factor, and unexplained factor group in this domain. Female factor group has scored higher than the other groups (Table 2).

For the variable total fertility problem, significant difference has been found between the groups (male factor, female factor, and unexplained factor) (P < .001) and gender (males and females) (P < .001). Females have scored higher than males in all 3 groups (Table 2).

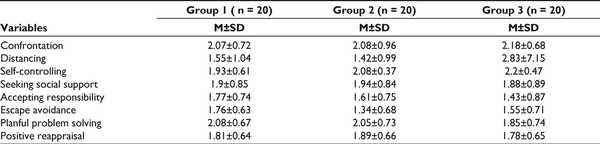

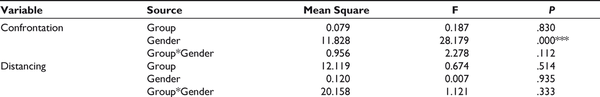

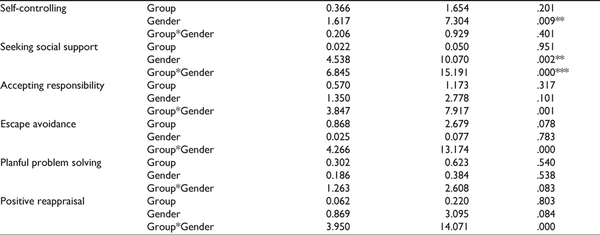

Males have scored higher than females in the male factor, female factor, and unexplained factor group in this domain. Male factor group has scored higher than the other groups. For the variable confrontation coping, significant difference has been found between the genders (males and females) (P < .001) (Table 3).

Significant difference has been found between the gender (males and females) (P < .001) for self-controlling coping. Males have scored higher than females in the male factor group. No significant difference has been found between males and females in the female factor and unexplained factor groups. Male factor group has scored higher than the other groups (Table 3).

For the variable seeking social support coping, significant difference has been found between the gender (males and females) (P < .001). Females have scored higher than males in the male factor and female factor group, whereas males have scored higher than females in the unexplained factor group. Unexplained factor group has scored higher than the other groups (Table 3).

Mean, standard deviation, and ANOVA were calculated. Mean was calculated to estimate the trend in data and summarize the typical value of the data set and standard deviation was calculated to see the spread of scores within the data set (Tables 2 and 3). ANOVA was done to analyze the differences among group means and their associated procedures (such as “variation” among and between groups) (Tables 4 and 5).

Discussion

Gender-Based Differences in Infertility

As compared to the other groups, in the current study, male factor group has the greatest social concern and females have greater social concerns than men. This dimension refers to the individual’s sensitivity to comments, reminders of infertility, feelings of social isolation, and alienation from family or peers. The reactions of the woman to her partner’s infertility can range from compassion, to shame, to deep resentment. Males acknowledge it is their problem irrespective of the fact whether they declare socially. They had no inhibitions to acknowledge their shortcoming. On the contrary, some women in the study reported that they would cover up for their husbands in their social circle and take the blame on themselves. She may have a need to protect him. Because the emphasis for pregnancy is on women in our society, many women seem more comfortable with outwardly taking responsibility for the couple’s infertility in front of families and friends.

Loss of Masculinity

Males tend to show greater sexual concern in comparison with females. This dimension refers to diminished sexual enjoyment and sexual self-esteem. The failure of their procreative body functions is often devastating for men, especially since they are so closely linked with sexuality. Men may consider it an assault on their masculinity. The ability to conceive a child has become a criteria for being a real man. Furthermore, the ability to conceive and the ability to continue the family tree are essential part of men’s masculinity and sexuality. Many people assume that infertile men cannot perform sexually. This stigma adds to the heightened insecurities in infertile men. Often, males do not show emotional stress in attempts to be the emotionally stable one within the relationship.

When a couple is ascertained to be suffering from infertility, regardless of who is more at fault, the male partner turns out to be comparatively more stressed out and hence, wallow in self-pity and indulge in acts of either remorse or denial or rationalization.

As a social convention, it is considered that for a man, his prowess lies in his sexual potency. This belief is so fiercely entrenched in the society that even a minor aberration or inadequacy is regarded as an unacceptable incapacity.

If our society did not ascribe that degree of importance to the concept of masculinity, then probably, much of the desperation and disenchantment amongst males could have been avoided. Such is the power of social belief that a nondescript male lacunae, invariably, leads to a self-punishing aggravation of one’s already existing weakness.

One aspect which has been much overlooked in this “warfield” is that once a couple seeks treatment for their infertility, all suggestions and advices become a matter of conscious striving to ameliorate a life of downswing, and as a result, the entire exercise becomes ritualistic or gets beset by act of lassitude. Much of the vigor which could have been instrumental in transforming the lives of the suffering couple, especially, the male partner, ebbs away under the hyperawareness catapulted by the treatment procedure. This state of affairs impose additional burden on the languishing man.

Sex may become a reminder of the couple’s failure to have a child. The increased intrusion into the sexual habits of the couples by the medical team’s recommendation for timed intercourse, frequent intercourse, or limited intercourse may make sex feel like a chore. The intimacy and pleasure usually derived from sexual relations may be identified as another loss by the couple.

Social Support and Relationship Concern

In the current study, overall relationship concern has been higher for females as compared to males. This dimension refers to difficulties in talking about infertility, understanding/accepting sex differences, and concerns about impact on relationship. In any social quagmire, support system is of vital importance, as it not only bolsters up motivation, but it also increases stress absorption capacity of human beings. In an infertile couple, just like a warring couple, it becomes crucial to have a supportive framework to emerge out of a crisis state. Women are more susceptible to infertility-related stress since in most human societies, womenfolk are given more onus of responsibility than their male counterparts.

The results of different studies showed that an increase in stress resulting from infertility may cause distress in marital relations and reduce women’s marital satisfaction. Furthermore, the results showed that infertility is more stressful in women than men which could be because of a higher relationship concern. An impact of moderate to severe infertility-related stress on depression has been observed. When pregnancy is delayed, the relatives may bring the couple under pressure to have a baby and this may cause worry. These factors bring negative attitude toward social acceptance because they are sensitive to this attitude and acceptance of relatives.

Need for Parenthood

Females have a higher need for parenthood as compared to men. This dimension refers to close identification with the role of parent and parenthood is perceived as primary or essential goal in life. Parenthood from the standpoint of social historicity is largely a matter of pride and satisfaction after a couple gets tied by the juxtaposed bond of marriage. Getting married, rearing up children, and nurturing them right into their adulthood, is an exercise of conventional choice and also an inescapable path in the lives of a married couple. Even though, in the post-modern times, many married couple decide to go without children, yet deep inside their personal lives, they sense a shuddering feeling of unbearable loneliness and chasm, yet they hardly have the courage to admit their predicament.

It was found in our previous study that infertile women were more depressed than men as they imagined themselves as mothers long before actually trying to have children and when this is withdrawn it resulted in feeling a loss of control. This study also noted that men and women desired children with similar intensities. Traditional society upholds the transition to parenthood as one that occurs following the marriage of a couple. Infertility can spoil this concept of an ideal normative transition and place feelings of guilt and shame upon couples and individuals grappling with the changing schema of their family identity. Despite the fact that over population is major problem in India, having children is firmly necessary for every married woman because infertility is the stigma of barrenness and the absence of the pleasures of motherhood. On some occasions, the very presence of an infertile woman is considered inauspicious, which add to the stigma of infertility. Many women reported that baby increases prestige in in-laws. If they were unable to give birth, they were largely blamed for infertility. Reproduction in the Eastern cultures holds the highest values and when childbearing seems impossible, probable psychological crisis sets in.

In the current study, it has been found that males used confrontation coping more than women. It describes aggressive efforts to alter the situation and suggests some degree of hostility and risk-taking. In this style of coping, individuals use both behavioral and cognitive strategies to eliminate the source of stress by changing the stressful situation. Engaging in problem solving activities related to infertility treatment, and planning for alternative family building strategies could also be a means of coping.

It was observed that women seek social support as a means of coping more than men. A study on 615 women seeking infertility treatment in southern Ghana found that women preferred to keep issues of their fertility problems to themselves which could be due to the associated stigma of infertility. This type of coping refers to seeking emotional support from people, one’s family, and one’s friends to deal with their problems. This could be informational support, tangible support, and emotional support.

Positive reappraisal was used more by women than men as a means of coping in the present study. Positive reappraisal is associated with reframing a situation and seeing it in a positive light. It describes efforts to create positive meaning by focusing on personal growth. It also has a religious dimension. We observed that they would try to cope by thinking more about the positive things in their life, try to do something meaningful, learn from their experience, see things positively, make the best of the situation, look on the bright side of things, find something good in what is happening, and try to do something that makes them feel positive. These would enable them to handle their distress better.

Men used self-controlling coping more than women in our study. This coping strategy describes efforts to regulate ones feelings and actions. This could be attributed to the fact that they keep their feelings to themselves through self-controlling strategies and emphasizing plans to solve the problem of infertility.

From the findings, it can be seen that to get an accurate picture of the infertility patient’s functioning and progress, the study of the psychological variables are important. Knowledge about the patient’s psychological health can further indicate the directions needed for more efficient treatment and help to bridge the gap between the clinician and the patient. Each of the variables studied are important for infertility patients irrespective of the etiology (male factor, female factor, and unexplained factor) and needs to be addressed.

Though the authors tried to maintain the qualities of a good scientific research, but some of the limitations could not be avoided like sample size estimation was not calculated based on the population to claim the proper representation, sample was collected only from one clinic, therefore, a particular strata could only be included, the data was collected through a single contact, as a result, with time whether psychological manifestations were changing could not be evaluated and this research depended on self-report findings. Information from other sources could not be obtained to confirm the findings of the self-report.

However, this particular study had some good strengths like this study included all three primary infertility groups, that is, male factor infertility, female factor infertility, unexplained factor infertility, most of the infertility studies focus on the female subjects, whereas this study collected data from both partners considering both of them as victims and we could control many psychosocial confounders through matching of the sample to minimize error.

Conclusion

Impact of infertility is evident with respect to fertility-related problems and different styles of coping of various types of infertility groups. Specific fertility-related problems like social concern and relationship concern is present more in females whereas, sexual concern is present more in males. Confrontation coping and self-controlling coping was used more by men, whereas women used positive reappraisal more and looked for social support more. In developing countries like India, psychological needs have not been addressed. Males have not been given importance and it is important to focus on both partners to improve the marital quality. The self-regulatory model of illness perceptions proposes that many features of one’s medical illness, namely its label, identity, short-term and long-term consequences, temporal course, causes, curability, and controllability affects the way people cope and recover from it. From this analogy, psychological distress due to a medical illness is higher if it is perceived as dangerous, life-changing, threatening, chronic, continuous, and incurable. Mental health professionals can help such patients address these issues with the help of a specifically devised psychotherapy. This study will enable psychological practitioners to incorporate this need. Fertility as a form of cult and a phenomenon of human empowerment have always propelled human societies into the state of parenthood. Marriage, sexuality, and children form a complex, yet the most closely woven triad of a fulfilling human existence.

From the existential perspective, infertility can not only act as a disastrous stumbling block to marital life, but it also has the potential to wreak havoc, unless (a) the couple comes together and chooses to prioritize their life goals and (b) the couple seeks concerted intervention to come out of the rut of shame, guilt, and hopelessness.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Shivaraya M, Halemani B. Infertility: psycho-social consequence of infertility on women in India. Indian J Soc Dev. 2007;7:309–316.

- 2. Manna N, Pandit D, Bhattacharya R, Biswas S. A community based study on infertility and associated socio-demographic factors in West Bengal, India. IOSR J Med Dent Sci. 2014;13(2):13–17.

- 3. Chatterjee S, Gon Chowdhury R, Dey S, Poddar V. Minor tubal defects—the unnoticed causes of unexplained infertility. J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;60(4):331–336.

- 4. Dhaliwal LK, Gupta KR, Gopalan S, Kulhara P. Psychological aspects of infertility due to various causes—prospective study. Int J Fertil Women’s Med. 2004;49(1):44–48.

- 5. Katiraei S, Haghighat M, Bazmi N, Ramezanzadeh F, Bahrami H. The study of irrational beliefs, defense mechanisms and marital satisfaction in fertile and infertile women. J Fam Reprod Health. 2010;4(3):129–133.

- 6. Levin JB, Sher TG, Theodos V. The effect of intracouple coping concordance on psychological and marital distress in infertility patients. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 1997;4(4): 361–372.

- 7. Ghaemi Z, Forousarih S. Psychosocial aspect of infertility. Int J Fertil Steril. 2010;4:87.

- 8. Fekkes M, Buitendijk SE, Verrips GHW, . Health-related quality of life in relation to gender and age in couples planning IVF treatment. J Human Reprod. 2003;18(7):1536–1543.

- 9. Sheehan KH, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, . The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;20:34–57.

- 10. Newton CR, Sherrard W, Glavac I. The Fertility Problem Inventory: Measuring perceived infertility-related stress. J Fertility Sterility. 1999:72(1);54–62.

- 11. Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Gruen RJ, DeLongis A. Appraisal, coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. J Personality Social Psychology. 1986;50(3):571–579.

- 12. Abdorrahimi L, Vafa LA. The role of the meaning of life in depression in infertile women. Int J Humanit Cult Stud. 2016;2(4):1769–1773.

- 13. Agarwal A, Mulgund A, Hamada A, Chyatte MR. A unique view on male infertility around the globe. J Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2015;13:37.

- 14. Agarwal RS, Mishra VV, Jasani AF. Incidence and prevalence of sexual dysfunction in infertile females. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2013;18(3):187–190.

- 15. Awtani M, Mathur K, Shah S, Banker M. Infertility stress in couples undergoing intrauterine insemination and in vitro fertilization treatments. J Human Reprod Sci. 2017;10(3):221–225.

- 16. Azghdy SB, Simbar M, Vedadhir A. The emotional-psychological consequences of infertility among infertile women seeking treatment: results of a qualitative study. Iranian J Reprod Med. 2014;12(2):131–138.

- 17. De Devika, Prasanta Roy K, Sarkhel S. A psychological study of male, female related and unexplained infertility in Indian urban couples. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2017;35(4): 353–364.

- 18. Boivin J. A review of psychosocial interventions in infertility. J Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:2325–2341.

- 19. De D, Mukhopadhyay P, Roy P. Experiences of infertile couples of West Bengal with male factor, female factor and unexplained infertility factor: a qualitative study. J Psychosex Health. 2020;2(2):152–157.

- 20. Donarelli Z, Coco G, Gullo S, . Infertility-related stress, anxiety and ovarian stimulation: can couples be reassured about the effects of psychological factors on biological responses to assisted reproductive technology? Reprod Biomed Soc Online. 2016;3:16–23.

- 21. Ehsan Z, Yazdkhasti M, Rahimzadeh M, Ataee M, Esmaelzadeh-Saeieh S. Effects of group counselling on stress and gender role attitudes in infertile women: a clinical trial. J Reprod Infertil. 2019;20(3):169–177.