Introduction

Penis image perception is an essential component of body image and is heavily culture-dependent. An individual usually draws his genital picture by his visual examination (of genital organs) followed by corroboration with his estimate, ideas, and beliefs. Most of these ideas and opinions are culturally framed and outcome of peer discussion. Most of the time, they lack any scientific basis and are associated with many false and magical sexual myths. This is more so because there is no open forum in the society where one can frankly discuss this issue or draw a healthy comparison with others’ genital organs. Individuals with high anxiety disposition or obsessive ruminative tendencies or hypochondriacal health concern are highly vulnerable to developing abnormal penis image perception. Those who are keen about their penis because of some reason (eg, impotence, sexual conflict, guilt or supposed or real sexual organ dysfunction) may show undue penis-awareness and engage themselves in repeated visual scrutiny. At this point, they usually attribute their sexual dysfunction and anxiety to self-alleged anatomic-physiological penis conditions. These conditions ultimately earn a “disease” or “abnormal” character at par with the subject’s sexual beliefs and misconceptions. There are many examples where psychosexual anxiety transmits to organ anxiety and makes a breeding ground for functional sexual morbidity. Dhat syndrome is a good example. Several research types have recently shown such clinical examples as small penis syndrome (SPS) or supposed penile deficiency in normal subjects. Those patients visit many health-care providers, including urology and sexually transmitted disease clinics. In psychiatry, persons with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)-spectrum personality traits or hypochondriacal health concerns are more prone to developing a sense of dismorphophobic penile perception.

Case Description

A 34-year-old single male from the northeastern state of Assam, from a semi-urban dwelling, education—Masters in Arts, profession—secondary school teacher, presented with the following complaints. For the last 10 years, he noticed that his penis is slowly getting reduced in size. This “small penis” thought was a constant botheration to him. About 3 years back, 1 night during sleep, he suddenly awakened, screamed with fear and extreme anxiety, and felt tingling and numbness in the genital area and lower limbs and felt that his penis is retracting into the abdomen, which he resisted by grasping it tightly. This episode lasted for about 15 min. He consulted a local practitioner but no permanent solution was offered. Now he is overwhelmed with this “penis” thought, mainly because his marriage negotiation is ongoing. He develops a ritualistic penis scrutiny at least 4 to 5 times a day. He also noticed that his left testis is smaller than the right one on repeated bodily scrutiny, which further intensified his genital anxiety. He was treated with a local herbal practitioner but discontinued treatment after 4 months. Afterward, he experienced a panic state of “shrinking penis” twice in the last 2 years, but the severity of the inward pull of the penis was mild, not drastic. Each episode was of an average duration of 5 to 10 min. All attacks occurred at night. Apart from this, he was also having multiple bodily symptoms like urinary urgency, dysuria, hesitancy, headache, and alleged liquidation of “dhat” (seminal fluid).

Clinical Assessment

On mental state examination, he was found with a high level of anxiety, low self-esteem and lack of confidence, low mood, low energy level, and lack of motivation with disturbed sleep (frequently broken sleep). His work performance and initiative also deteriorated. At age 24, he left masturbatory habits because of extreme guilt and gathered information from a local healer that masturbation causes sexual weakness. There was no history of any heterosexual experience. He had previous knowledge of the Koro epidemic in the locality a few months ago. The Koro attacks were with a typical presentation with sudden feelings of retraction of the penis inside the abdomen with severe anxiety and autonomic arousal features. The ideational component of Koro anxiety was not fear of death but impotency and losing sexual power. The first attack was quite severe, but subsequent attacks were of the “mild” type.

On physical examination, left-sided atrophied testis was detected. Later, semen analysis showed plenty of nonmobile sperms with pathological forms. No morphological abnormality of the penis is noted. He was of average built without any systemic disease.

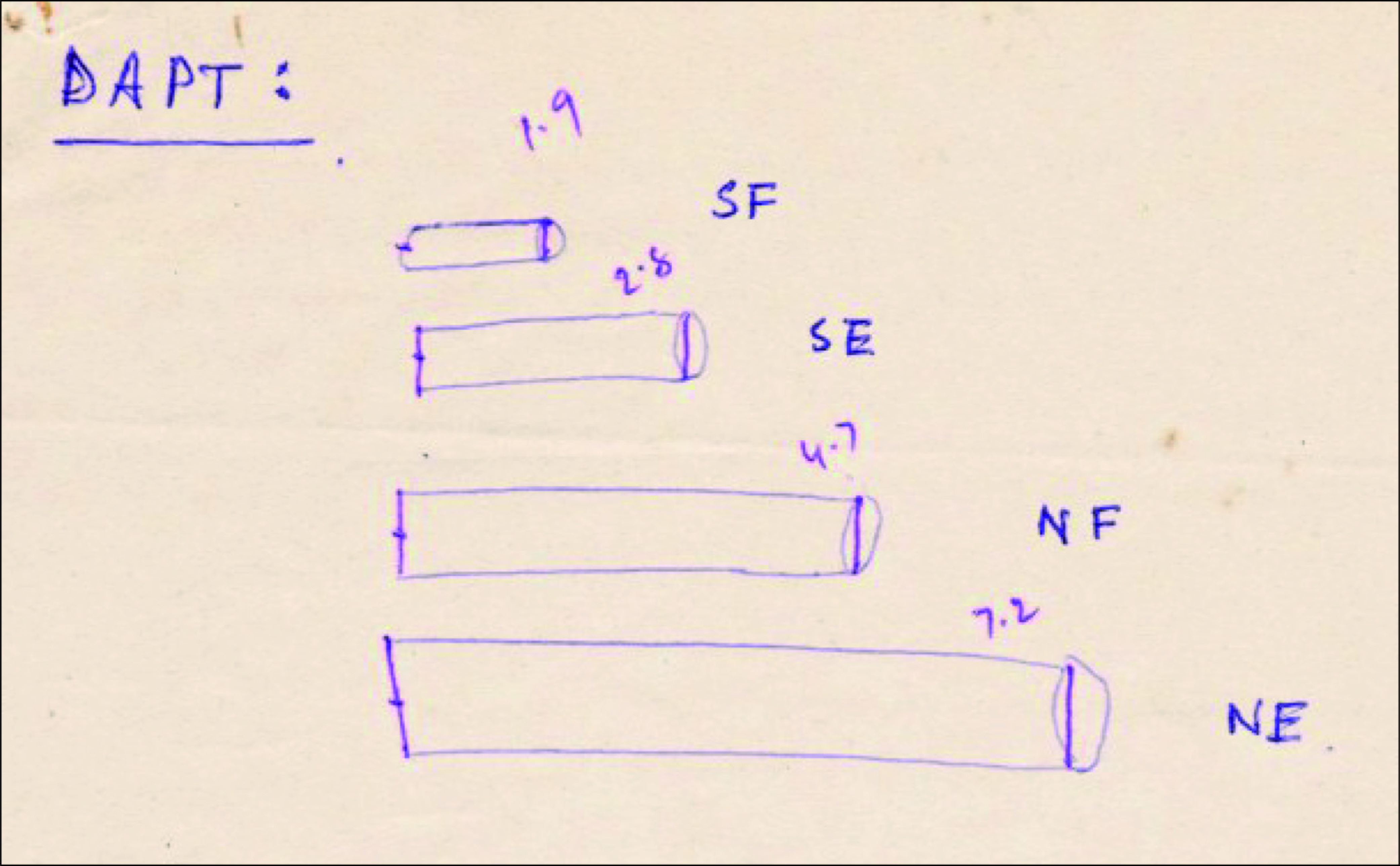

Projective drawing of the penis at first clinical contact: He has small penis perception compared to normal penis length perception on Draw-a-penis Test (DAPT) drawings. DAPT drawings on penis length showed the following values: self penis—flaccid length (SF): 1.9 cm, extended state (SE): 2.8 cm. Perception of the average penis: flaccid state (NF) 4.7 cm and extended state (NE) 7.2 cm (Figure 1). Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) was used to measure the perceived penis length also.

Figure 1

DAPT Drawings of the Subject

Source: The authors.

All the laboratory blood test and electrocardiogram was normal. Depression rating on Hamilton 17-item scale was 21 (moderate depression), and Trait anxiety on Bengali adapted State-Trait Anxiety Inventory was 48.2 (mean reference range for average person 34.5 and generalized anxiety disorder 52.6).

Management

He was treated with Tab Clomipramine 50 mg initially and then after 1 week 50 mg twice for 2 weeks and then 100 mg twice daily to continue, along with Tab Clonazepam 0.5 mg at bedtime. He also had 3 cognitive behavioral therapy-oriented educational discussions on sexual anatomy and physiology with a clinical psychologist and reassured him that he has an average penis length. It seemed that he was gaining confidence and felt that his ideas about penis length might not be “fully correct.” He also believed that the episodes of a penis shrinking were real. His Hamilton score improved to 14 at 12 weeks follow-up. He dropped out after 5 follow-up visits (after 5 months).

The VAS measurement in cm showed gradual improvement in his penis length perception as follows:

First rating: Length of the flaccid penis at premorbid level (10 years ago): 6.5 cm

First rating: Length of the flaccid penis at the beginning of the problem (3 years ago): 4.6 cm

Second rating: Length of the flaccid penis after 6 weeks of treatment: 4.3 cm

Third rating: Length of the flaccid penis after 12 weeks of treatment: 6.1 cm

Surprisingly, after 2 years, he wrote a letter to the first author that he has married and having good marital consumption. His wife attested that he has no abnormality in shape or size. He also thanked the team for providing practical educational sessions.

Discussion

The penis is a symbol of masculinity. In Indian cultural milieu, like many other cultures, it also symbolizes attributes such as strength and power, manliness and sexual competence, and procreative power. By definition, SPS is a subjective perception that his penis length or girth is less than a normal person’s penis and caused a high emotional concern (anxiety and depression) with behavioural impairment in their daily life activities. This concern or conviction is usually due to obsessive rumination or a manifestation of body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) or maybe a genital delusional perception in psychosis. BDD is a fixed idea of an imaginary defect or flaw in a body part’s morphological or physical appearance. It is usually associated with depressive disorder. Veale et al defined penile dysmorphophobia (PDD) as a subjective conviction where “the size or shape of the penis is their main, if not their exclusive, the preoccupation is causing significant shame or handicap.”

The case’s detailed clinical analysis showed a definite anxious predisposition with hypochondrical genital concern complicated with recurrent Koro episodes. The small penis preoccupation is the culmination of several factors like heightened anxiety about sexuality especially concerning ongoing marriage negotiation, longstanding dysmorphophobic concern with penis size (for the last 10 years) left-sided atrophied testis may be a potent trigger. But good response as reflected on VAS scores with Clomipramine indicates that this penile dysmorphophobic concern was not fixed but amenable to treatment. So the most important clinical question remains whether he has small penis syndrome? If it is so, then PDD can shift to SPS with therapeutic intervention or present in a mixed form. Clinicians should be conscious of this dual possibility while dealing with cases with abnormal penile perception. Recurrent Koro is usually rare but in a vulnerable individual may be a manifestation of intensification of genitally focused anxiety, initially precipitated by knowledge of a local Koro epidemic. Koro patients do have dismorphophobic penile perception with high-trait anxiety levels. A similar case of recurrent Koro with diminishing severity who had remission of symptoms after marriage was reported from England 40 years ago.

This case is posing some debate over its diagnostic status. His chief complaint was the perception of small penis length over a long period accompanied by obsessive genital scrutiny, anxiety, and depression. This fulfills the criteria for hypochondriacal disorder (PDD with hypochondriasis)—ICD 10 Code F 45.2. Given his standard penis size (on physical examination) with high-trait anxiety, he also fulfills small penis syndrome diagnosis. There is no diagnostic code for SPS; it may be a part of obsessive preoccupation or a part of BDD. Koro in the midst of this may be considered as a supplementary clinical entity that was aggravated by pre-Koro genital concern (PDD) and knowledge of the Koro epidemic in the locality.

A clear clinical distinction among OCD, BDD, SPS, and Koro is warranted. It is recalled here that DSM-5 devised a category called “obsessive-compulsive or related disorder” (300.3). Three specific types of body dysmorphic like-disorders are included: (1) body dysmorphic like-disorder with actual flaws; (2) body dysmorphic like-disorder without repetitive behaviors, and (3) body-focused repetitive behavior disorder. It also contains 3 so-called culture-bound syndromes, including Koro. So if we keep the broad OCD spectrum in mind, then all the different clinical presentations of BDD, SPS, and Koro will be clear. Of course, BDD, SPS, and genitally focused hypochondriacal health concern are closer to the OCD spectrum but Koro is not. In this case, the OCD personality traits of the patient increase the vulnerability to Koro, especially after a local epidemic of Koro. At the same time, many Koro patients have underlying penile dismorphophobic concerns as well, and this perception may influence the clinical spectrum of their Koro presentation.

The interrelationship between OCD and BDD is strong. Several groups of BDD patients showed a high lifetime prevalence of OCD rates (34-78%). The lifetime rates of BDD in OCD are also found to be high (ranging from 8-37%). Recent research have shown that the OCD spectrum is an expanding clinical umbrella under which disorders like BDD, subclinical BDD, hypochondriasis, eating disorder, and some impulse-control condition share important OCD feature. BDD, like OCD, also responds to treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and clomipramine. But there is some clinical difference between OCD and BDD thought process. In BDD, the beliefs indicate poor insight with dystonic character loss like overvalued ideas, which is usually not evident in OCD thoughts.

Another debate arise is whether PDD is a cultural manifestation of BDD. Culture has a substantial impact on the perception of body image. Veale et al in their study with BDD and PDD, found some environmental and cultural risk factors (like genitalia teasing by peers) in BDD development compared with men without any penile concern. Cultural perception by significant others, assessment and appreciation, and value judgments positively or negatively influence body image. Koro itself is a culture-bound syndrome by itself. Further research is needed to unfold the different cultural gradient impact potential on the body image perception in general and penis image in particular.

His improvement in penis perception after the therapeutic intervention and his very positive communication later strongly advocates that proper psychoeducation and tricyclic antidepressant drugs offer good clinical recovery of penile dysmorphophobic perception.

Conclusion

Clinical evaluation of abnormal genital perception needs thorough history taking. The therapeutic success depends heavily on medication plus psychoeducation on genitourinary morphology and function. Careful clinical scrutiny about OCD spectrum disorders is essential for correct diagnostic formulation. Koro may be precipitated at the background of a dismorphophobic penile perception, especially in the climate of a Koro epidemic.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Declaration The authors are thankful to the patient for giving informed consent for his case’s unanimous presentation. It was obtained by respecting his right to privacy and taken in a manner consistent with the World Health Organization guidelines and Helsinki’s declaration.

Funding The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Chowdhury AN. Variations in the perception of penis. J Sex Health. 1993;3:156–160.

- 2. Wylie KR, Eardley I. Penile size and the “small penis syndrome”. BJU Int. 2007;99(6):1449–1455.

- 3. Lee PA, Reiter EO. Genital size: a common adolescent male concern. Adoles Med. 2002;13(1):171–180.

- 4. Chowdhury AN. Draw-a-penis test (DAPT). J Person Clin Stud. 1989;5:97–100.

- 5. Chowdhury AN. Bengali adaptation of Spielberger’s STAI, Form X. J Person Clin Stud. 1989;5:257–260.

- 6. Hamilton MA. A rating scale for depression. J Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62.

- 7. Veale D, Miles S, Read J, Troglia A, Carmona L, Fiorito C . Penile dysmorphic disorder: Development of a screening scale. Arch Sex Behav. 44(8): 2311–2321.

- 8. Gieler T, Brahler E. Body dysmorphic disorder: Anxiety about deformity. Hautarzt. 2016; 67 (5): 385–390.

- 9. Chowdhury AN. Dysmorphic penis image perception - The root of Koro vulnerability. Acta Psychiat Scand. 1989; 80, 518–520.

- 10. Chowdhury AN. Trait anxiety profile of Koro patients. Ind J Psychiatry. 1990;32:330–333.

- 11. Barrett K. Koro in a Londoner. Lancet. 1978;ii:1319.

- 12. APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder. DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- 13. Altamura C, Paluello MM, Mundo E, Medda S, Mannu P. Clinical and subclinical body dysmorphic disorder. Europ Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;251:105–108.

- 14. Hollander E, Cohen LJ, Simeon D. Body dysmorphic disorder. Psychiat Annals. 1993;23:359–364.

- 15. Bienvenu OJ, Samuels JF, Riddle MA, . The relationship of obsessive-compulsive disorder to possible spectrum disorders: results from a family study. Biolog Psychiatry. 2000;48: 287–293.

- 16. Stein DJ. Neurobiology of the obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. Biolog Psychiatry. 2002;47:296–304.

- 17. Marks I, Mishan J. Dysmorphophobic avoidance with disturbed bodily perception: a pilot study of exposure therapy. Brit J Psychiatry. 1988;152:674–678.

- 18. Spurgas AK. Body image and cultural background. Sociol Inq. 2005;75(3):297–316.

- 19. Veale D, Miles S, Read J, Muir GH. Environmental and physical risk factors for men to develop body dysmorphic disorder concerning penis size compared to men anxious about their penis size and men with no such concerns: a cohort study. J Obsessive Compuls Disord. 2015;6:49–58.

- 20. Featherstone M. Body, image and affect in consumer culture. Body Soc. 2010;16(1):193–221.