Introduction

The number of temporary workers in the medical profession is rising and this trend looks set to continue.– Locum doctors are essential for maintaining continuity of service, and healthcare organisations use locums to cover gaps in rotas due to absence or recruitment and retention problems and also to fill service gaps in remote and rural areas. The exponential growth in the use of locum doctors in recent years has been previously related to shortages of medical staff and crises in the healthcare workforce. Shortages have been related to a number of factors including a national lack of responsibility for workforce issues and workforce planning and high numbers of doctors leaving their jobs early. Rising locum numbers and the associated increase in cost has led to a growing concern among policymakers, employers and professional associations about locum use.–

Locums are sometimes perceived to present a greater risk of causing harm to patients than permanent doctors. Some high-profile locum failures in practice over recent years have brought into question the quality and safety of locum doctors. The presence of locums in the work environment has been described as an ‘error producing condition’, which is attributed in part to their lack of familiarity with local teams, processes, guidelines and practices.– The peripatetic nature of locum work is thought to present a risk in and of itself as locum doctors are less likely to be enveloped in regulatory practices and receive less oversight from supervisors and employing organisations. Furthermore, recent data from the General Medical Council show that locum doctors are more likely to be the subject of complaints, more likely to have those complaints subsequently investigated and more likely to receive sanctions. However, the reasons behind these risks and complaints are not well understood and the General Medical Council has acknowledged that information about locum doctors is lacking.

Locum doctors are subject to the same standards and regulations as other doctors. Yet, despite guidelines and policies being issued by UK regulators and organisations relating to locum regulation, employment and practice, recent evidence has highlighted weaknesses in the oversight of locum doctors, and suggests that these policies may not be fully implemented. The use of locum doctors has continued to be seen as a ‘weak link’ in the chain of clinical governance. The presence of these gaps in the system can lead to organisational blind spots. Identifying these blind spots in governance, and potential solutions, is likely to lead to improvements in patient safety and has been identified as priority by NHS England.

With current projections indicating that the number of doctors working as locums will continue to rise, it is clear that a better understanding of the quality and safety of locum doctor working is needed to improve the use of locum doctors and the quality and safety of patient care that they provide. This paper presents a narrative review of the evidence relating to the quality and safety of locum medical practice. Its purpose is to develop our understanding of how temporary working in the medical profession might impact on quality and safety and to help formulate recommendations for practice, policy and research priorities.

Methods

A systematic search of electronic databases (Ovid Medline, PsycINFO, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the Health Management Information Consortium) was conducted in April 2018 including citation searching and manual reference list screening. The wider literature was searched using Google Scholar and we searched a range of websites for relevant reports, such as The King's Fund, the Department of Health, the General Medical Council, Grey Literature Report and OpenGrey. Documents were also gathered through experts and contacts in the UK and internationally, including leading practitioners in the medical profession and senior officials with responsibility for the regulation and governance of the medical profession.

Our search strategy was purposefully broad in order to identify both the empirical literature and wider literature relating to locum quality and safety. Papers eligible for inclusion in the review were written in English and provided information or evidence relating to the quality and safety of locum doctors. Given that there have been longstanding concerns about locum doctors, no date restrictions were imposed on the search (e.g. Ovid Medline 1946 – April 2018, PsychInfo 1806 – April 2018).

Paper titles were screened by one of the authors (JF) and potentially relevant papers were obtained in full. Full-text empirical papers that met the inclusion criteria were assessed for eligibility and methodological quality using the relevant Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklists dependent on the study methodology. Non-empirical papers were not formally assessed for quality.

The empirical and non-empirical literatures were synthesised separately. For empirical papers, data on study location, objectives, sample characteristics, methods, findings and methodological quality were extracted in tabular form (Table 1). For non-empirical papers, the title, publisher, author, date of publication, country and document type were reported, as well as a short summary of their key points on locum quality and safety (Table 2). A narrative approach to synthesis was used because the few empirical papers were heterogeneous in methods, settings and outcomes.

Findings

Search results

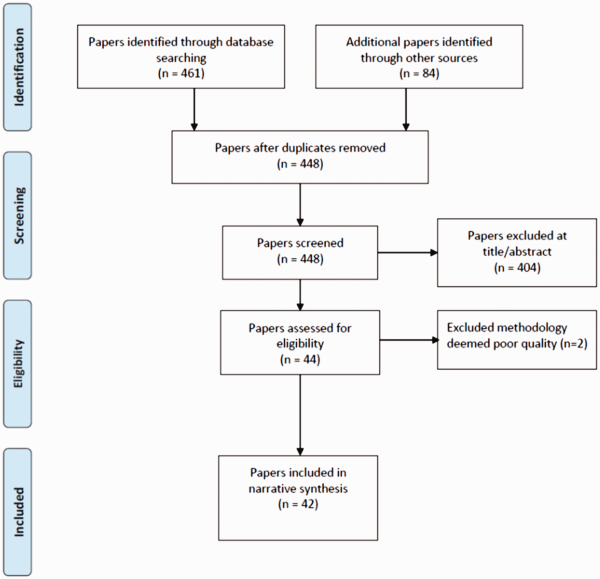

Database searching identified 461 papers; a further 84 papers were identified from other sources. Following removal of duplicates, 448 remaining papers were screened and 404 were excluded at title/abstract level. Two empirical papers were excluded because of methodological weaknesses. This left a total of 42 papers (eight empirical papers and 34 non-empirical papers) for the review. We did not find any existing review papers on locum doctor working. Figure 1 highlights the stages of paper selection and review.

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram.

Empirical findings on the quality and safety of locum medical care

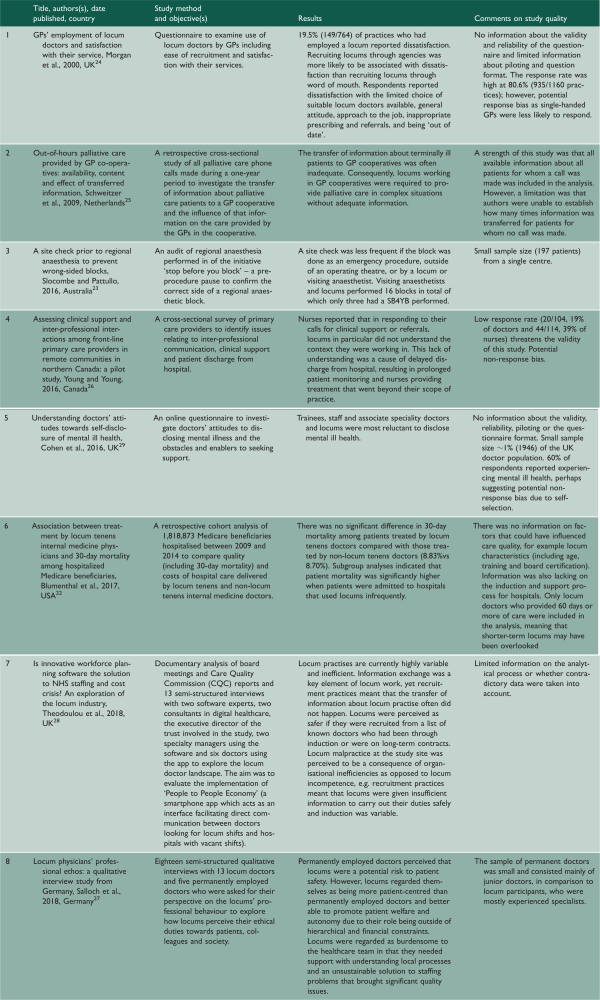

The eight empirical papers identified are summarised in Table 1. Almost all are relatively small studies using surveys or interviews to explore various aspects of locum doctor practice. Often they have small sample sizes, low response rates and other methodological limitations.

The most substantial study we identified compared 30-day mortality, costs of care, length of stay and 30-day readmissions in the United States for a random sample of 1,818,873 Medicare patients treated by locums or by permanent doctors between 2009 and 2014. There were no significant differences in 30-day mortality rates between patients treated by locums compared to permanent doctors; however, cost of care and length of stay were significantly higher when patients were treated by locums. Furthermore, in subgroup analyses, significantly higher mortality was associated with treatment by locums when patients were admitted to hospitals that used locums infrequently, perhaps due to hospitals being unfamiliar with how to support locums. Only locum doctors who provided 60 days or more of care were included in the analysis, meaning that shorter-term locums, who may have had less opportunity to become familiar with the organisation, may have been excluded.

Other papers examined locum medical practice in settings such as anaesthesia, primary care– and hospital medicine, and some explored doctors' attitudes to and experience of locum working., Overall, there was some limited empirical evidence to suggest that locums may have a detrimental impact on quality and safety.–,, This was attributed in part to locum doctors being less likely to be familiar with patients and less aware of local policies and processes, which had a number of consequences, including delays in discharging patients and safety procedures being less likely to be carried out. There was some qualitative evidence to suggest that working with locums was viewed unfavourably by other doctors as their lack of familiarity could be burdensome for other healthcare professionals, who reported having to work outside of their scope of practice in order to compensate for locum unfamiliarity with local contexts. Locum working was sometimes regarded as a problematic solution to staffing problems that had potential quality issues.

Factors which may affect the quality and safety of locum medical care

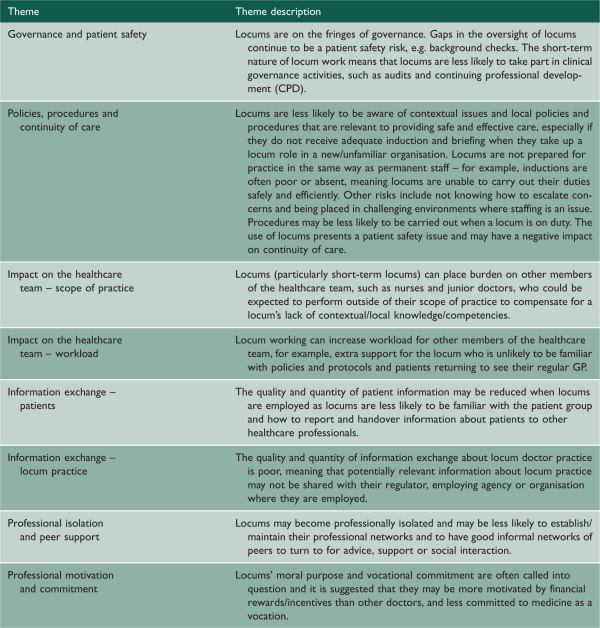

Our search identified 34 non-empirical papers. Most were from the UK (24), while four were from the USA, three from Canada and one from the Netherlands. Most papers focused largely on the poor governance or regulation of locum working and the associated risks or problems of quality and safety. Eight recurring themes regarding quality and safety of locum practice were identified and are outlined in Table 2.

Findings from this wider literature (which is summarised in Table A1 in online Appendix 1) indicated that a lack of robust systems around the employment of locum doctors presented a number of potential risks to safety and quality. This was attributed to, for example, inadequate pre-employment checks and induction, unclear line management structures, poor supervision and lack of reporting of performance.,,,,,– Locums were described as professionally isolated and less likely to be aware of the local context necessary for delivering safe and efficient care.,,,, This was regarded as not only detrimental to patient safety, but this lack of preparation for practice may also be potentially detrimental to locum wellbeing and the wider healthcare team who might have to work beyond their scope of practice to compensate for the locums' lack of knowledge. Other inefficiencies related to locum working included increased workload for the healthcare team if patients returned to their usual doctor after initially seeing a locum, resulting in duplication and waste of resources. The quality and quantity of information exchange about locum working was described as absent or poor.–, Furthermore, inadequate record keeping and reporting may have also meant that poorly performing locums were able to move between organisations without their performance issues being addressed.,,,

Discussion

This is the first review of the evidence relating to the quality and safety of locum doctors. We have already noted that there have been growing concerns about the quality, safety and cost of locum doctors among policymakers, employers, regulators and professional associations, and that this has led organisations such as NHS Employers and NHS England to produce guidelines for organisations using locums, locum agencies and locums themselves. However, our review suggests that there is relatively little empirical evidence to support assertions about the quality and safety of locum practice, and to provide an evidence base to support the development of such guidelines.

There does seem to be some consensus in the literature that there are a number of factors which plausibly may affect the quality and safety of locum practice, some of which are concerned essentially with locum doctors themselves, but most of which are really about the organisations who use locums and the ways in which they are deployed and supported. While it is clearly reasonable to expect that locum doctors take personal responsibility for their own professional development, and display the same commitment to the medical profession as other doctors, it seems likely that the quality and safety of locum practice is fundamentally shaped by the organisational context in which they work. Our review has highlighted eight key factors (Table 2), six of which pertain to organisational context. It suggests that organisations should ensure that locums are fully included in systems for clinical governance including clinical audit, continuing professional development and appraisal; that policies and procedures should be fit for use by locum doctors as well as permanent staff and should not presume knowledge of or familiarity with local processes; that there should be careful consideration of the scope of practice of locum doctors and their integration into the wider clinical team; and that information flows, handover procedures and communications need to take account of locum working arrangements. Importantly, it suggests that organisations have a responsibility if they have concerns about a locum to deal with them fairly, constructively and properly and to liaise fully with both the locum and the locum agency involved and, if necessary, with the General Medical Council.

The lack of robust evidence about the quality and safety of locum practice is perhaps, in part, because this is a difficult topic to research. Routine sources of data do not generally identify whether care was provided by a locum doctor, and often care is provided by a team which may consist of both locum and permanent doctors and it is difficult to distinguish the separate contributions of each. Indeed, the term ‘locum doctor’ itself may be unhelpful, as it includes everything from those working in permanent positions but undertaking some additional work as a locum to those who work for all or most of their time as a locum, and locum positions which may last as long as several months or more to assignments where a locum may work for as little as a single shift or a few days in an organisation. But it does seem clear that more research is needed to examine empirically the differences that exist between the practice and performance of locum and permanent doctors, to develop our understanding of the factors which influence the quality and safety of locum working, and to provide an evidence base for guidance to healthcare organisations, locum agencies, regulators and, of course, locum doctors themselves.

Conclusion

Overall, we conclude that there is very limited empirical evidence to support the many commonly held assumptions about the quality and safety of locum practice, or to provide a secure evidence base for the development of guidelines on locum working arrangements. It is clear that future research could contribute to a better understanding of the quality and safety of locum doctors working and could help to find ways to improve the use of locum doctors and the quality and safety of patient care that they provide.

References

- 1. General Medical Council. Secondary Care Locums Report, Manchester: General Medical Council, 2015.

- 2. Staff Care. 2017 Survey of Temporary Physician Staffing Trends, Dallas: Staff Care, 2017.

- 3. Zimlich R. The rise of locum tenens among primary care physicians. Med Econ 2014; 91: 58.

- 4. General Medical Council. What Our Data Tells Us about Locum Doctors, Manchester: General Medical Council, 2018.

- 5.

- 6. Iacobucci G. “Unfairness” of locums' higher pay must be tackled, says NHS chief. BMJ 2017; 356: j502.

- 7.

- 8. The Royal College of Surgeons of England. Locum Surgeons: Principles and Standards, London: The Royal College of Surgeons of England, 2011.

- 9. CQC. Investigation into the Out-of-Hours Services Provided by Take Care Now London, London: Care Quality Commission, 2010.

- 10. Dean B, Schachter M, Vincent C, Barber N. Causes of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a prospective study. Lancet 2002; 359: 1373–1378.

- 11. Jennison T. Locum doctors: Patient safety is more important than the cost. Int J Surg 2013; 1: 1141–1142.

- 12. Godlee F. Time to face up to the locums scandal. BMJ 2010, pp. 340: c3519 .

- 13. Isles C. How I tried to hire a locum. BMJ 2010, pp. 340: c1412.

- 14. Department of Health. Code of Practice: Appointment and Assessment of Locum Doctors, London: Department of Health, 2013.

- 15. Pearson K. Taking Revalidation Forward: Improving the Process of Relicensing for Doctors, London: General Medical Council, 2017.

- 16. Tazzyman A, Ferguson J, Hillier C, Boyd A, Tredinnick-Rowe J, Archer J, et al. The implementation of medical revalidation: an assessment using normalisation process theory. BMC Health Serv Res 2017; 17: 749.

- 17.

- 18. Fotaki M, Hyde P. Organizational blind spots: Splitting, blame and idealization in the National Health Service. Hum Rel 2015; 68: 441–462.

- 19. NHS Improvement. Agency Controls: Expenditure Reduced by £1 Billion and New Measures, London: NHS Improvement, 2017.

- 20. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Appraisal Checkilists, Oxford: Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2018.

- 21. Ryan R. Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group: Data Synthesis and Analysis, London: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2013.

- 22. Blumenthal DM, Olenski AR, Tsugawa Y, Jena AB. Association between treatment by locum tenens internal medicine physicians and 30-day mortality among hospitalized medicare beneficiaries. JAMA 2017; 318: 2119–2129.

- 23. Slocombe P, Pattullo S. A site check prior to regional anaesthesia to prevent wrong-sided blocks. Anaesth Intensive Care 2016; 44: 513–516.

- 24. Morgan M, McKevitt C, Hudson M. GPs' employment of locum doctors and satisfaction with their service. Fam Prac 2000; 17: 53–55.

- 25. Schweitzer B, Blankenstein N, Willekens M, Terpstra E, Giesen P, Deliens L. GPs' views on transfer of information about terminally ill patients to the out-of-hours co-operative. BMC Palliat Care 2009; 8: 19.

- 26. Young TK, Young SK. Assessing clinical support and inter-professional interactions among front-line primary care providers in remote communities in northern Canada: a pilot study. Int J Circumpolar Health 2016; 75: 1.

- 27. Salloch S, Apitzsch B, Wilkesmann M, Ruiner C. Locum physicians' professional ethos: a qualitative interview study from Germany. BMC Health Serv Res 2018; 18: 333.

- 28. Theodoulou I, Reddy AM, Wong J. Is innovative workforce planning software the solution to NHS staffing and cost crisis? An exploration of the locum industry. BMC Health Serv Res 2018; 18: 188.

- 29. Cohen D, Winstanley SJ, Greene G. Understanding doctors' attitudes towards self-disclosure of mental ill health. Occup Med 2016; 66: 383–389.

- 30. Jones PF, Ramsay AD. Errors by locums. BMJ 1996; 313: 116–117.

- 31.

- 32. Audit Scotland. Using Locum Doctors in Hospitals, Edinburgh: Audit Scotland, 2010.

- 33.

- 34.

- 35. Pariser P, Biancucci C, Shaw SN, Chernin T, Chow E. Maximizing the locum experience. Can Fam Physician 2012; 58: 1326–1328.

- 36.

- 37. The King's Fund. How can dermatology services meet current and future patient needs while ensuring that quality of care is not compromised and that access is equitable across the UK? London, 2014.

- 38. Jumper NG. Locums earn more but have extra charges and fewer opportunities. BMJ 2017, pp. 356: j961 .

- 39. Murray R. The trouble with locums. BMJ 2017, pp. 356: j525.

- 40.

- 41. Medical Board of Australia. Building a Professional Performance Framework, Canberra: Medical Board of Australia, 2017.

- 42. Chapman R and Cohen M. Supporting organisations engaging with locums and doctors in short-term placements: A practical guide for healthcare providers, locum agencies and revalidation management services, Unpublished report, 2018.

- 43. Rimmer A. Locum cap will lead to staff shortages and patient safety risks, official assessment warns. BMJ 2015; 351: h5674.

- 44. Tolls RM. The practice of locum tenens: views from a senior surgeon. Bull Am Coll Surg 2008; 95: 8–10.

- 45.

- 46.

- 47.

- 48.

- 49.

- 50. Wright P. Workforce strategies focus too much on recruitment, rather than maximising the contributions of locums to general practice. Br Med J 2016; 355: i5877.

- 51. Oxtoby K. How the popularity of life as a locum is changing the health service. Br Med J 2016: 354: i4297.

- 52. Rimmer A. Locums withdrawing work in wake of tax change must consider impact on patients, GMC says. BMJ 2017; 357: j1785.

- 53.

- 54.

- 55.

- 56. Perkins C. Reflections of a psychiatric mercenary: on being a locum. Australas Psychiatry 2017; 25: 448–450.

- 57.