Introduction

Persistent genital arousal disorder/genitopelvic dysesthesia (PGAD/GPD) is characterized by persistent or recurrent, unwanted or intrusive, distressing sensations of genital arousal and/or other symptoms of GPD that persist for ≥3 months. These sensations are not associated with concomitant sexual interest, thoughts, or fantasies., PGAD symptoms negatively affect patients’ relationships, mental health, and daily function. Furthermore, PGAD/GPD is commonly associated with despair, emotional lability, catastrophization, and/or suicidality. Limited epidemiologic studies in the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada suggest that approximately 0.6% to 3.0% of people experience symptoms consistent with PGAD, implying that a significant number of individuals are affected by this distressing condition. Multiple psychological and medical factors may contribute to the development and maintenance of PGAD/GPD. These factors may be characterized as originating in the end organ (region 1), pelvis and perineum (region 2), cauda equina (region 3), spinal cord (region 4), and/or brain (region 5).

Since PGAD symptoms were correlated with the occurrence of Tarlov cysts in the cauda equina, and surgical treatment of these cysts alleviated the PGAD,, we concluded that there exists a subgroup of patients with PGAD/GPD and Tarlov cyst–induced sacral radiculopathy. Within the context of this article, sacral radiculopathy is defined as (1) inflammatory irritation of the S2-S3 nerve roots in the cauda equina that are formed by the convergence of the pelvic, pudendal, and sciatic nerves and (2) clinical symptoms that involve the sensory fields of these nerves. Using a multidisciplinary step-care management algorithm, we evaluated this subgroup of patients with neurogenital testing, sacral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and caudal epidural anesthetization. On sacral MRI, some patients with PGAD/GPD had lumbosacral annular tear pathology rather than Tarlov cysts, which was confirmed on lumbar MRI. It became evident that PGAD/GPD could also result from lumbosacral annular tear–induced sacral radiculopathy, a finding not previously reported. We confirmed this hypothesis using a revised multidisciplinary step-care management algorithm to evaluate responses on neurogenital testing, lumbosacral MRI, transforaminal epidural spinal injection (TFESI) anesthetization, and surgical treatment of the lumbosacral annular tear that alleviated the PGAD/GPD.

Surgical treatment of the lumbosacral annular tear was performed through minimally invasive lumbar endoscopic spine surgery (LESS). LESS has been shown to successfully treat patients with lumbosacral annular tears that cause low back and leg pain. As compared with conventional spine surgery, LESS reduces paraspinal muscle injury, minimizes blood loss, decreases postoperative pain, and shortens recovery times. Thus, LESS is considered an appropriate surgical strategy in patients diagnosed with PGAD/GPD from lumbosacral annular tear–induced sacral radiculopathy.

Methods

This was an independent review board–approved study. Clinical data were collected on a cohort of patients with PGAD/GPD treated between August 2016 and November 2020 in the spine–sexual medicine program who had a history consistent with PGAD/GPD for ≥3 months and underwent LESS with at least 1-year postoperative follow-up. Patients provided informed consent for all diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Our spine–sexual medicine program uses a biopsychosocial approach by a multidisciplinary team (spine surgery, sexual medicine, sex therapy, physical therapy, and behavioral neuroscience). Data included demographics, psychological assessment, diagnostic testing results, surgical complications, and LESS treatment outcomes.

Multidisciplinary step-care management algorithm

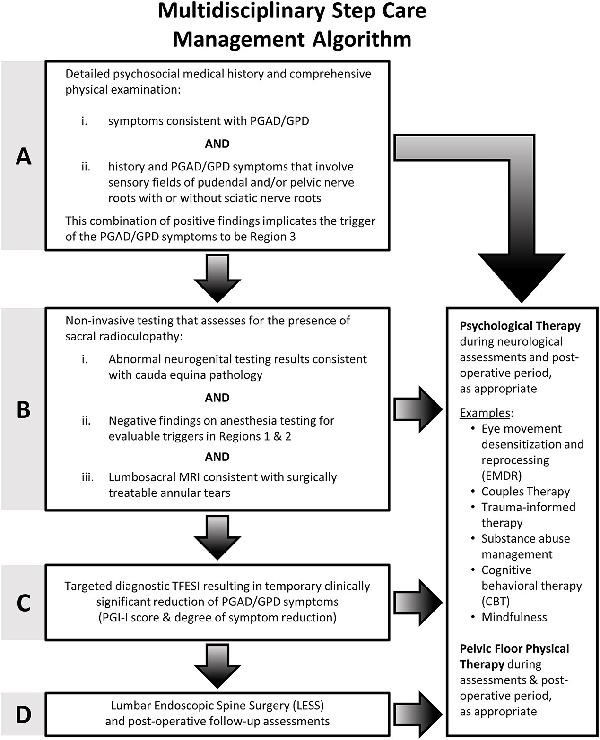

A 4-stage step-care management algorithm (Figure 1) was developed to identify patients with PGAD/GPD suspected of having lumbosacral annular tear–induced sacral radiculopathy and to select candidates for treatment by LESS. We recognize the diversity of gender identities and the importance of using gender-inclusive language. People of all genders may be affected by PGAD/GPD, though all of our study subjects are incidentally cisgender individuals. Thus, for clarity, the words women and men are used in this article to refer to patients assigned female and male sex at birth, respectively, with the knowledge that evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment are applicable to all patients irrespective of their gender identities.

Figure 1

Step-care management algorithm outlining the criteria used in the present study for treatment of PGAD/GPD annular tear–induced sacral radiculopathy via LESS. LESS, lumbar endoscopic spine surgery; PGAD/GPD, persistent genital arousal disorder/genitopelvic dysesthesia.

Step A: comprehensive biopsychosocial evaluation

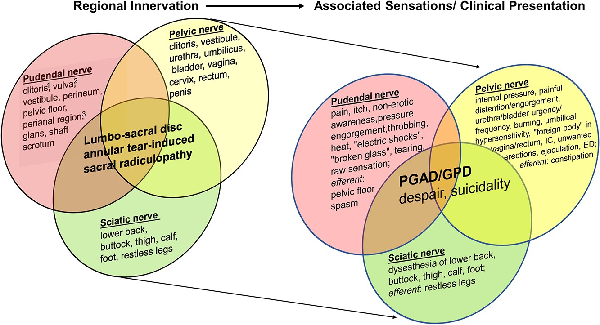

The step-care management algorithm starts with identifying patients who fulfill the criteria for having PGAD/GPD. It involves a biopsychosocial assessment to identify those with PGAD/GPD who have concomitant mental health and biologic history and symptoms. As part of the sexual medicine intake, all patients are administered a standard battery of validated instruments: the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) for women; the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) for men; and for all patients, the Sexual Distress Scale–Revised, the Perceived Stress Scale, and the Patient Health Questionnaire–9. Concerning mental health issues (eg, depression/anxiety), our evaluation determines how the patients’ symptoms affect their quality of life, how patients feel about themselves, and whether they are experiencing any past trauma or current relationship issues. Regarding biologic issues, our evaluation is aimed at identifying history and symptoms that involve sensory fields of pelvic, pudendal, and sciatic nerves that have converged as cauda equina sacral nerve roots (S2, S3) (Figure 2). In terms of pelvic floor issues, our evaluation assesses pelvic floor and extrapelvic regions as potential generators of or contributors to PGAD/GPD from soft tissues.,, Based on our multidisciplinary evaluation, referrals to specialists are made as appropriate.

Figure 2

Regional innervation (left side) and associated sensations/clinical presentation (right side) in patients with lumbosacral annular tear–induced sacral radiculopathy. The bodily locations of specific symptoms are differentially related to the sensory fields of the corresponding pudendal, pelvic, and sciatic nerves. Consequences of the constellation of symptoms and the underlying pathology are represented by the overlap in these characteristics. Pudendal nerve branches include dorsal nerve branch, perineal nerve branch, and inferior hemorrhoidal nerve branch.

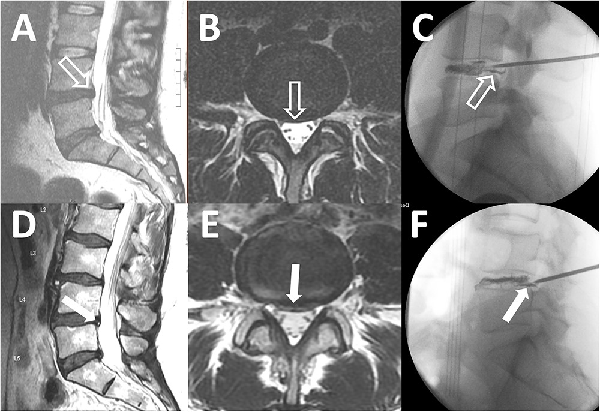

Figure 3

Magnetic resonance imaging: (A) normal findings with no pathology; (B) abnormal findings with multiple abnormalities not suitable for surgery.

Figure 4

Subtle and obvious annular tears. T2 sagittal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), T2 axial MRI, and the corresponding intraoperative discogram images show annular tears in patients with a subtle annular tear (A-C) and an obvious annular tear (D-F). A small bulging disc at L4-L5 without an associated high-intensity zone (HIZ) is indicated in panels A and B (open white arrows). Intraoperative discogram images reveal leakage of contrast through the annular tear (C, open white arrow). A bulging disc with an obvious HIZ is highlighted in panels D and E (solid white arrows). Intraoperative discogram images demonstrate leakage of contrast through the annular tear corresponding to the HIZ on MRI (F, solid white arrow). Note that there are also obvious annular tears at L5-S1 in panels A and D.

Step B: noninvasive assessment for the presence of lumbosacral annular tear–induced sacral radiculopathy

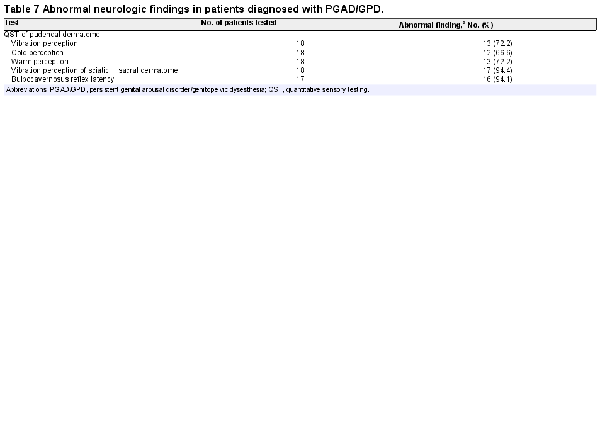

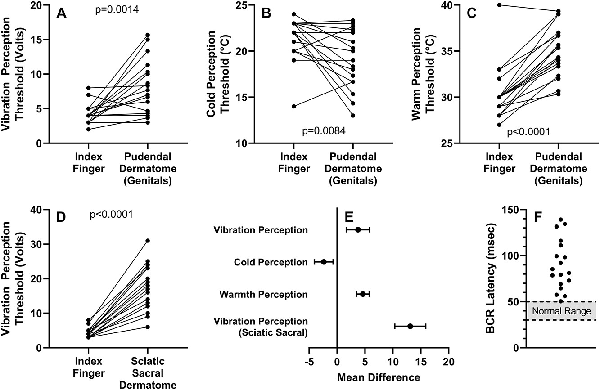

In our study cohort, noninvasive assessment for the presence of lumbosacral annular tear–induced sacral radiculopathy was performed through neurogenital testing, regional anesthesia testing, and lumbosacral MRI. Neurogenital testing consists of quantitative sensory testing (QST), sacral dermatome testing, and bulbocavernosus reflex (BCR) latency testing and has been previously described. Patients with PGAD/GPD in the study cohort who had abnormal findings on all 3 neurogenital tests were considered to have a pattern consistent with sacral radiculopathy. Patients with abnormal QST and BCR latency test results but normal sacral dermatome findings were considered to have a pattern consistent with PGAD/GPD from pudendal neuropathy and not sacral radiculopathy. Patients with abnormal QST and abnormal sacral dermatome but normal BCR latency test results were considered to have a pattern consistent with PGAD/GPD pathology above the conus medullaris, including upper spinal cord and/or brain, and not sacral radiculopathy.

A thorough physical examination was performed to test for possible PGAD/GPD triggers in region 1 (end organ) or region 2 (pelvis/perineum), as described previously. In our study cohort, when positive testing was identified in region 1 or 2, local anesthesia tests were performed., If these patients had persistent PGAD/GPD symptoms despite having numbness to cotton-tipped swab and/or deep palpation, it was hypothesized that their PGAD/GPD trigger was not in region 1 or 2 but closer to the central nervous system (ie, region 3, 4, or 5).

A third aspect of step B was for the spine surgeon to assess the lumbosacral MRI for the presence of a surgically treatable lumbosacral annular tear., All lumbosacral MRI had to have been of appropriate technical quality and performed within 12 months of clinical evaluation. The use of contrast material during the MRI procedure was not required unless there was previous lumbosacral spine surgery at the site of the annular tear. The following lumbosacral MRI categorization system was utilized. The patient was not considered a surgical candidate if there were no lumbosacral annular tears (Figure 3A) or if the patient had multilevel abnormalities where risks of surgery outweighed benefits (Figure 3B). The patient was a surgical candidate if the lumbosacral MRI revealed annular tears at 1, 2, or 3 spinal levels that could be treated by LESS. We then further classified the annular tear by severity per the following criteria: subtle if a disc bulge or protrusion was visualized but there was no accompanying high-intensity zone (Figure 4, A and B) and obvious if a high-intensity zone was visualized on the axial and sagittal T2-weighted images (Figure 4, D and E).

Step C: diagnostic TFESI

Patients who met all the criteria of steps A and B were referred to a pain medicine specialist for diagnostic TFESI to test whether administration of a local anesthetic agent at the site of the suspected annular tear would result in clinically significant reduction of the PGAD/GPD symptoms within the first 4 hours of injection. The pain medicine specialist performed the diagnostic TFESI using fluoroscopic or computed tomography–guided imaging, administering to a specific location a low-volume injectate (1 mL) containing either an anesthetic alone (eg, preservative-free 1% lidocaine or 0.25% bupivacaine) or a 50/50 mixture of an anesthetic and a corticosteroid. Patients completed a symptom diary with the Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I) and the percentage degree of change of symptoms. The PGI-I is a validated patient-reported outcome measure based on a 7-point Likert scale., A diagnostic response to the TFESI was considered positive if patients reported a PGI-I score of 1, 2, or 3 and a 50% reduction of symptoms.

Step D: lumbosacral endoscopic spine surgery

Patients with PGAD/GPD who met criteria for steps A to C in the management algorithm were considered candidates for endoscopic discectomy/annuloplasty with LESS. This technique is well described for the treatment of patients with back pain and radiculopathy.,, With a mixture of methylene blue and intravenous contrast media, a chromatodiscogram was performed to outline the annular defect (Figure 4, E and F). The annular defect on chromatodiscogram was identified in patients with subtle and obvious annular tears. The blue stain produced by the leakage of the methylene blue through the annular defect marked the pathologic area of the disc. Fragments of nucleus material trapped within the fissures of the posterior annulus were removed. Discrete tears and fissures in the annulus were ablated with the endoscopic radiofrequency probe (Trigger-Flex; Elliquence) and YAG-holmium probes (Lumenis). All patients were discharged the same day.

Assessment of surgical outcome

Surgical outcome was assessed by postoperative PGI-I. Patients reporting a PGI-I score of 1, 2, or 3 were considered to have clinically meaningful improvement. Follow-up, including PGI-I score and adverse events, was performed at 1 week, 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, and ≥2 years. The 90-day postoperative adverse events were graded on the Clavien-Dindo classification system, a scale from 1 to 5 based on increasing severity and the type of intervention required to treat the complication. All patients in this study had a minimum 1-year follow-up.

Results

The study cohort consisted of 20 cisgender patients who underwent LESS. Through the multidisciplinary step-care management algorithm, 168 patients with PGAD and symptoms of arousal in the genitopelvic area were evaluated over a 51-month period between August 2016 and November 2020. Of these, we identified 20 patients (12%) who met the criteria for this study cohort based on the management algorithm. LESS procedures in these 20 patients were performed over a 33-month period from October 2016 to July 2019.

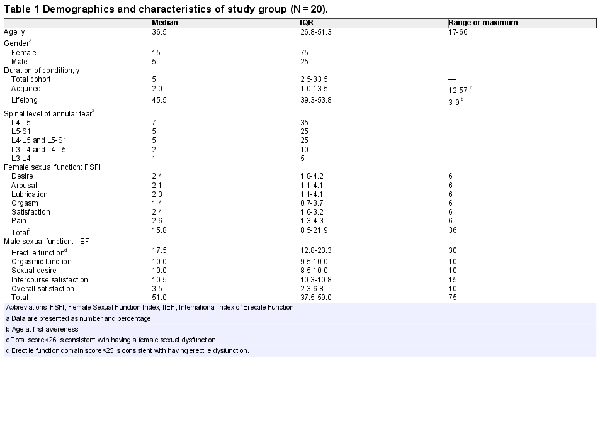

Demographics and characteristics

The demographics and characteristics of our study cohort are described in Tables 1 to 3. Most patients (80%) had an acquired form of PGAD/GPD, but 20% had symptoms that were first realized between the ages of 3 and 9 years, which were considered lifelong (Table 1). In women, all domains of the FSFI were consistent with a multidimensional sexual dysfunction. In men, the lowest domain score of the IIEF was overall satisfaction. The mean erectile function domain score was consistent with mild erectile dysfunction. One patient had no erectile dysfunction (IIEF erectile function score >26). Table 2 identifies by location the various unwanted genitopelvic arousal symptoms consistent with the diagnosis of PGAD. These distressing sensations of genital arousal were most commonly experienced in the clitoris/penis, vagina, and urethra.

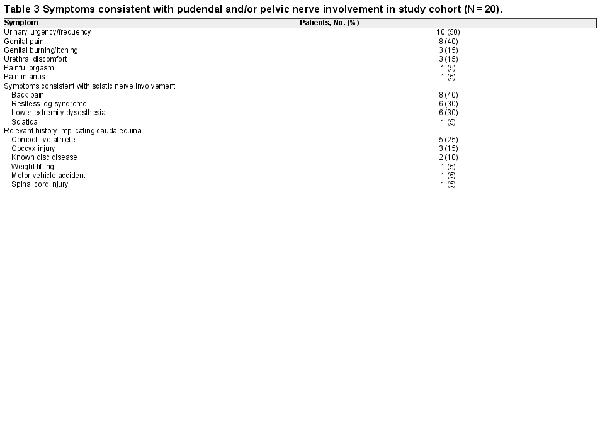

Many patients with PGAD in this cohort had concomitant symptoms and histories indicative of sciatic or pelvic nerve involvement (Table 3). Symptoms consistent with the sensory fields and functions of the sciatic nerves included back pain (40%), restless leg syndrome (30%), and lower extremity dysesthesia (30%). Symptoms consistent with the sensory fields and functions of the pelvic nerves were urinary urgency/frequency (50%) and urethral discomfort (15%). Symptoms consistent with the sensory fields and functions of the pudendal nerves consisted of genital pain (40%) and genital burning/itching (15%).

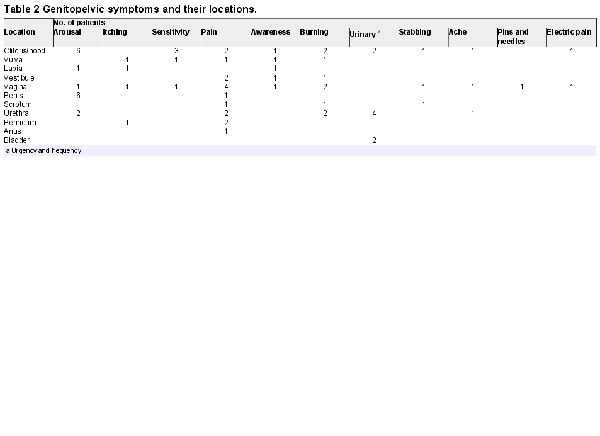

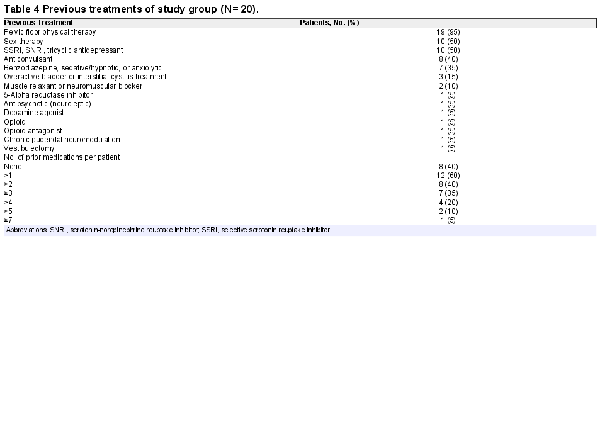

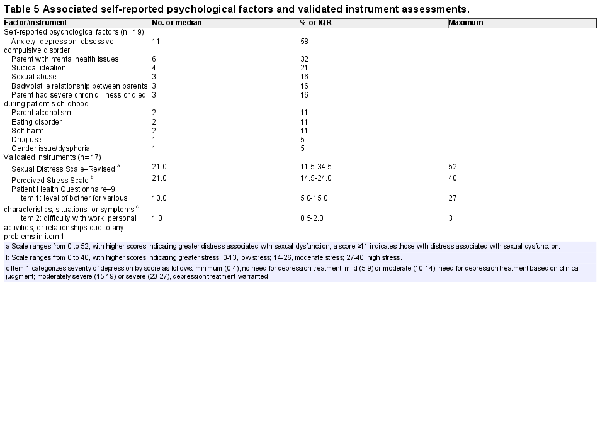

Consistent with previous practice that the most common triggers of PGAD were in regions 1, 2, and 5, patients in our study cohort underwent multiple treatments prior to being assessed for annual tear-induced sacral radiculopathy (Table 4). Our study cohort had parent/family mental health issues and exhibited high levels of anxiety, depression, and/or obsessive-compulsive disorder and suicidal ideation (Table 5). The Sexual Distress Scale–Revised revealed significant distress in 14 patients (82%). The Perceived Stress Scale showed 3 patients (18%) having low stress, 12 (70%) having moderate stress, and 2 (12%) having high stress. As assessed by item 1 of the Patient Health Questionnaire–9, 10 subjects had a score consistent with the need for depression treatment based on clinical judgment, and 3 had a score consistent with warranting treatment for depression. As assessed by item 2 (“How difficult is it for you to do your work, take care of things at home, or get along with other people?”), 5 reported somewhat difficult, 5 very, and 3 extremely.

Neurologic and regional anesthesia testing

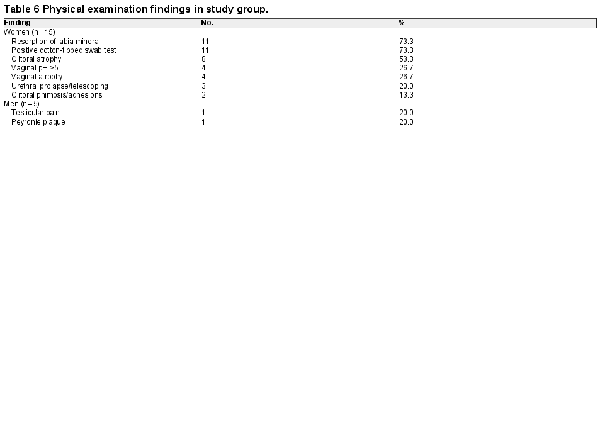

Each patient underwent a comprehensive physical examination of regions 1 and 2, with findings of the study cohort summarized in Table 6. Neurogenital testing was performed in 18 of 20 patients; 17 completed all 3 tests with abnormal findings (Table 7) consistent with cauda equina pathology. Individual test values are shown in Figure 5. Region 1 anesthesia testing was performed in 8 women who complained of pain in the clitoris/vestibule and/or had pain on cotton-tipped swab testing of the genitals during vulvoscopy. In all cases, local anesthesia failed to eliminate PGAD/GPD symptoms despite the genital-provoked pain being ameliorated, consistent with a concomitant diagnosis of clitorodynia, vestibulodynia, or genitourinary syndrome of menopause. One male patient who complained of penile pain underwent a dorsal nerve block as a region 1 anesthesia test; however, his penile pain symptoms were not clinically significantly reduced. Region 2 anesthesia testing via pudendal nerve block was performed in 8 patients, none of whom had clinically significant symptom reduction. These findings implied that the underlying triggers for our PGAD/GPD study cohort were closer to the central nervous system (ie, region 3, 4, or 5).

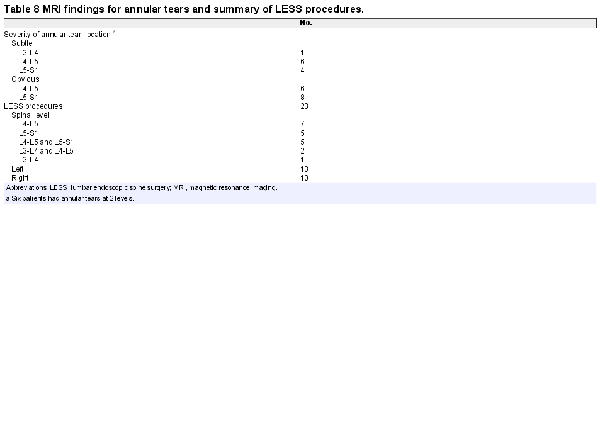

MRI findings and TFESI testing

According to our criteria for severity, 10 patients were considered to have a subtle annular tear and 10 an obvious annular tear on lumbosacral MRI (Figure 4). As seen in Table 8, the most common locations were L4-L5 and L5-S1; 6 patients had annular tears at both these levels. These are common locations of lumbosacral spine injury, perhaps related to the transition zone between the flexible spine and the rigid sacrum., TFESI was performed in these patients, as determined by the multidisciplinary step-care management algorithm (Figure 1). All patients had a positive TFESI result, with a PGI-I score of 1, 2, or 3.

Surgical procedures and outcomes

Based on MRI findings, a total of 22 LESS procedures were performed in 20 patients (Table 8). One patient had bilateral annular tears and underwent LESS on the left side, followed by LESS on the right side 6 months later. Another patient had a fall 1 month after surgery that reactivated her symptoms, and she underwent a repeat LESS procedure at 4.5 months after the first operation. All patients were discharged the same day, with no readmissions.

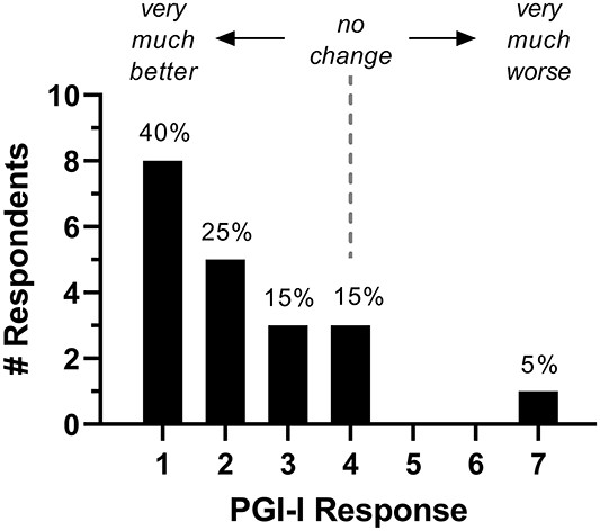

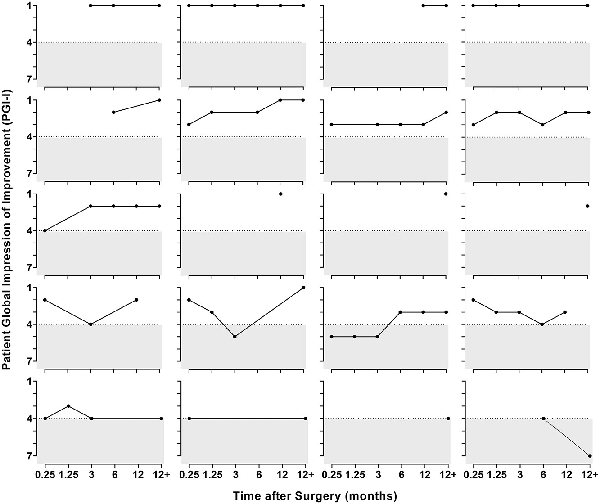

The average follow-up was 20 months (range, 12-37 months). There were no surgical complications based on the Clavien-Dindo classification system (grades 1-5).,, At most recent follow-up, 16 of 20 patients (80%) reported improvement on the PGI-I (score of 1, 2, or 3; Figure 6), with 65% (13/20) indicating significant improvement (PGI-I score 1 or 2). PGI-I scores were not significantly different between patients with subtle and obvious annular tears. However, patients with acquired PGAD/GPD had a median postoperative PGI-I score of 1.5 (n = 16) as opposed to 3.5 (n = 4) for those with lifelong PGAD/GPD. Individual scores over time are presented in Figure 7. Among 13 patients for whom data were available within 3 months of surgery, 11 (85%) reported improvement per the PGI-I; 9 (69%) of whom had a score of 1 or 2 (very much better or much better). One patient indicated no change for 6 months after surgery but subsequently experienced worsening of her condition.

Discussion

PGAD/GPD is a bothersome and distressing condition associated with abnormal genitopelvic sensations, especially unwanted arousal, that result in catastrophization and suicidality and likely affects millions of individuals worldwide. The condition was first characterized in 2001. From 2001 to 2011, efforts to treat patients with PGAD were focused, in part, on the genitopelvic area and included the treatment of clitorodynia/vestibulodynia, pelvic floor physical therapy, pudendal neuropathy,,, and embolization of pelvic varicosities for pelvic congestion syndrome. During that period, pharmacologic treatments for PGAD were aimed at increasing brain inhibitory activity by utilizing opioids, GABAergic agonists, and serotonergic agonists., Other treatment strategies consisted of psychotherapy, counseling, hormone therapy, and electroconvulsive therapy. Prior to 2011, a subgroup of patients with PGAD were unresponsive to these biopsychosocial management strategies. In this subgroup, the implication was that the treatments were not based on a comprehensive understanding of their underlying PGAD pathophysiology.

It was not until 2012 that Tarlov cyst–induced sacral radiculopathy was suspected as a trigger for PGAD in some patients. Subsequently, patients with Tarlov cyst–induced sacral radiculopathy were successfully treated by surgery., This led us to focus for the first time on the cauda equina as a source of the PGAD pathology. In the course of evaluating the sacral MRI of patients with PGAD, we frequently observed lumbosacral annular tears. We hypothesized that PGAD could also be associated with lumbosacral annular tear–induced sacral radiculopathy and successfully treated by surgery.

Given our new awareness that a subgroup of patients with PGAD could have cauda equina pathology, we initiated a new clinical study. This study utilized a novel multidisciplinary step-care management algorithm designed to identify a subgroup of patients with PGAD/GPD (n = 20) with lumbosacral annular tear–induced sacral radiculopathy who could benefit from LESS. Furthermore, this study evaluated long-term patient safety and efficacy outcome data (≥1-year follow-up). Thus, our study cohort represents a very specific subgroup of patients with PGAD/GPD. Our study demonstrated that 80% of these patients experienced improvement following LESS per the PGI-I. There is not, however, a validated outcome instrument specific for PGAD/GPD.

PGAD/GPD associated with annular tear–induced sacral radiculopathy

The data show that our patients had a combination of symptoms of genitopelvic and lower extremity dysesthesia (Tables 2 and 3) related to the sensory fields of the pudendal, pelvic, and sciatic nerves. These clinical symptoms may have been accounted for by irritation of sacral nerve roots in the cauda equina (region 3), which can produce sensations that are perceived as originating in peripheral regions. Sacral roots (S2-S4) entering the cauda equina ascend through the lumbar region toward the first synapse in the conus medullaris. The pudendal, pelvic, and sciatic nerves converge at the S2/S3 foramina and comprise the S2/S3 nerve roots. Thus, sacral nerve roots en passage can be irritated mechanically or chemically by annular tear–induced lumbar disc pathology. This irritation of the sacral nerve roots can lead to PGAD/GPD symptoms that include genitopelvic and lower extremity dysesthesia. The concept that irritation of nerve roots in the cauda equina (region 3) can produce sensations that are perceived as originating in distant peripheral regions is analogous to the well-known condition of sciatica, in which pain is perceived as originating in the buttocks and lower extremities but is commonly the result of cauda equina pathology. In parallel, PGAD/GPD symptoms typically perceived as arising from the genitopelvic region (eg, unwanted clitoral arousal to the verge of orgasm and bladder, vaginal, rectal, lower extremity, and/or lower back dysesthesia) can be a consequence of a neuropathology that occurs at a site remote from the location of the perceived symptoms, specifically from a lumbosacral annular tear–induced sacral radiculopathy within the cauda equina.

Figure 5

Neurogenital testing results. Integrity of the dorsal and perineal branches of the pudendal nerve was assessed by genital sensation threshold to vibration (A) and to cold (B) and warm (C) temperatures. Sciatic nerve integrity was assessed by sacral dermatome sensation threshold to vibration (D). (E) Mean differences (95% CIs) between test sites and reference control (index finger) for quantitative sensory testing values. (F) Bulbocavernosus reflex (BCR) latency values in the study group with the reference range indicated by the shaded region.

Symptomatic annular tears and chronic irritation of the dura and nerve roots

It is well known that the extrusion of the nucleus pulposus outside its anatomic compartment may result in a chronic inflammatory state modulated by factors such as interleukin 1β, interleukin 6, and tumor necrosis factor., We hypothesized that in patients with symptomatic subtle or obvious annular tears, as identified by targeted diagnostic injections, this chronic inflammation results in irritation of the dura and sacral nerve roots. During surgery, we observed that even subtle annular tears show erythema of the dura, consistent with the presence of chronic inflammation. Therefore, the primary goal of surgical treatment in patients with PGAD/GPD with lumbosacral annular tear–induced sacral radiculopathy is to remove the agents inducing and perpetuating chronic inflammation (ie, disc fragments and nucleus pulposus material trapped within the epidural space and the fissures of the annular tear).

Our outcome data revealed that the LESS procedure performed on patients with subtle annular tears was equally effective in the improvement of PGAD/GPD symptoms as compared with those who had obvious annular tears. This suggests that it is the chronic irritation to the sacral nerve roots that causes PGAD/GPD. This is particularly relevant because subtle annular tears are not often reported as abnormal findings in the lumbar MRI; thus, some patients with PGAD/GPD with subtle annular tears do not undergo evaluation for suspected lumbosacral annular tear–induced sacral radiculopathy.

PGAD/GPD and cauda equina syndrome

There are some characteristics in common between PGAD/GPD and cauda equina syndrome (CES). Both involve irritation of sacral nerve root fibers of passage through the lumbar region that convey sensation perceived as originating from the genitopelvic area and lower extremities. However, there are 2 major differences between these conditions. CES is an emergency due to severe lumbosacral disc herniation that acutely compromises the integrity of the lumbosacral nerve roots. CES involves efferent dysfunction (eg, bladder and bowel) with some perceptual pain or numbness in the lower extremity. The CES literature occasionally refers to sexual medicine disorders in men, such as erectile dysfunction, but rarely references sexual dysfunction in women. By contrast, PGAD/GPD is a chronic sexual medicine condition of relatively low-level nerve root irritation that can result in a range of genitopelvic abnormal afferent sensations.

Multidisciplinary step-care management algorithm

Due to the multiple possible regions of PGAD/GPD pathology (genital, pelvis/perineum, cauda equina, spinal cord, and brain), we recognized the need for a logical diagnostic sequence (Figure 1) to evaluate that subgroup of patients with PGAD suspected of having an annular tear–induced sacral radiculopathy contributing to their condition (Figure 2). Use of this step-care management algorithm enabled careful selection of patients for the LESS procedure.

Step A involved a detailed psychosocial and medical history that enabled us to identify patients who had symptoms consistent with PGAD/GPD (Table 2). As shown in Figure 2, these symptoms were perceived as originating from various combinations of the sensory fields of the pudendal (S2-S4), pelvic (S2-S4), and sciatic (L4-S3) nerves, implying cauda equina pathology. Psychosocial history is also obtained in step A. In our study cohort, we identified high levels of anxiety, depression, parent/family mental health issues, and suicidal ideation. Examples of parent/family mental health issues included the parent exhibiting obsessive-compulsive behavior, having bipolar disorder, being emotionally unavailable, and frequently having multiple sexual relationships in the home.

Figure 6

Distribution of PGI-I scores obtained at the most recent follow-up after LESS (mean follow-up, 20 months; range, 12-37). LESS, lumbar endoscopic spine surgery; PGI-I, Patient Global Impression of Improvement.

Figure 7

Time course of PGI-I scores in individual patients after surgery. PGI-I, Patient Global Impression of Improvement.

In addition, the validated instruments used to identify stress, distress, and depression revealed psychological concerns in the majority of patients in our study cohort. A review of the literature in this field shows that those afflicted with PGAD experience difficulty with mental health issues (eg, depression, worry, and stress) and substantial difficulties with psychosocial adjustment., Studies have shown that anxiety may reinforce, exacerbate, and maintain PGAD. These findings emphasize that PGAD can be a devastating disorder causing marked distress and loss of quality of life. In our study cohort, 19 of 20 patients who underwent the LESS procedure had a preoperative assessment by our sex therapist, and 18 of these 19 were advised to undergo counseling after surgery. As noted in our study cohort, research in this area has shown that those afflicted with PGAD have a high incidence of mental health issues even prior to PGAD symptoms. Women and men were assessed by the FSFI and the IIEF,, respectively, to identify if they had multidimensional sexual dysfunction. Of note, Leiblum and Seehuus found that the FSFI was not a sensitive measure of sexual dysfunction in women with PGAD. This may be due to the fact that some individuals with PGAD are driven to increased need for genital stimulation by their condition. We believe that in our study cohort, which engaged women with a broader symptomatology that included GPD (eg, persistent and unwanted itching, burning, throbbing, and pain), their condition may be associated with an aversion for genital stimulation. In contrast to Leiblum and Seehuus’s conclusion, our results revealed the FSFI to be a sensitive instrument for sexual dysfunction. Of the 5 men in our study cohort, 4 had bothersome and distressing GPD. In this case, the IIEF was also sensitive in identifying their sexual dysfunction.

Step B included performing neurogenital testing of the integrity of the sciatic and pudendal nerves. There are, however, no established clinical tests of pelvic nerve involvement in patients with PGAD/GPD. If a patient has dysesthesia symptoms related to the sensory field of the pelvic nerve (eg, sensation of foreign object in vagina/rectum) in combination with symptoms related to the pudendal and sciatic nerves and has never had radical pelvic surgery or radiation to the pelvis, there is most likely involvement of the cauda equina. This finding is particularly relevant in patients with clitorodynia. Waldinger et al reported a case of a woman with clitorodynia who underwent a pudendal nerve block. This block resulted in clitoral numbness, but the pain persisted (negative test). Due to patient insistence, a clitoridectomy was subsequently performed. Postoperatively, the patient continued to experience clitorodynia, now in the “phantom” clitoris. Based on our present evidence, it is likely that the source of the clitoral pain was remote from the clitoris and potentially evoked within the cauda equina by a Tarlov cyst or an annular tear–induced sacral radiculopathy. This could have been supported by lumbosacral MRI.

In a systematic review of 33 articles reporting imaging findings for >3000 asymptomatic individuals, the prevalence of disc protrusion (subtle annular tear) and obvious annular tear varied from 29% to 43% and from 19% to 29%, respectively, in individuals aged 20 to 80 years. Thus, the finding of an annular tear on lumbosacral MRI, either subtle or obvious, is not meaningful without additional information. In our cohort of patients with PGAD/GPD, abnormal lumbosacral MRI findings in conjunction with the results of the other minimally invasive diagnostic tests (end organ/pudendal nerve anesthesia testing and neurogenital testing) provided sufficient rationale to advance to the next phase of the algorithm.

In step C, a TFESI was performed by a pain medicine specialist. The TFESI may be associated with nausea, headache, fainting, dizziness, and serious adverse events such as infection, bleeding, dural puncture, nerve damage, and sciatica. Thus, it is important to use the step-care management algorithm to carefully identify those patients with PGAD/GPD who are appropriate candidates for the TFESI. In our study cohort, there were no serious adverse events associated with the TFESI.

Step D included LESS and postoperative follow-up. Many patients derive further benefit from postoperative psychologic therapy and/or pelvic floor physical therapy.

Impact of psychological factors on recovery

Since psychological factors contribute to the development, continuation, and consequences of PGAD/GPD and since our patient cohort experienced significant mental health issues, it is our experience that recovery from LESS is more protracted in patients with PGAD/GPD than typically experienced after LESS for lower extremity sciatica. Thus, psychological counseling is beneficial and should be continued postoperatively as needed (eg, ≥12 months). Addressing psychological concerns in the postoperative period with psychological therapy (Figure 1) could enhance quality of life.

Adjunctive postoperative pelvic floor physical therapy

Postoperative physical therapy should be performed by a pelvic floor physical therapist skilled in spinal rehabilitation. In our study cohort, 19 of 20 patients (95%) underwent concomitant pelvic floor physical therapy to reduce dysesthesia during the early postoperative recovery phase. Postoperative physical therapy should start 2 to 4 weeks following surgery; however, a paced walking program could begin earlier. Goals of physical therapy include rehabilitation of the muscles surrounding the lumbosacral annular tear pathology to adjunctively reduce irritation on lumbosacral nerve roots and to improve patients’ overall function during activities of daily living while eliminating or minimizing their dysesthesia. Patients’ with PGAD/GPD also need to feel safe in communicating with the pelvic floor physical therapist about their dysesthesia, as well as associated bowel, bladder, and sexual dysfunctions.

Study strengths and limitations

The strength of this study is our novel multidisciplinary step-care management algorithm that was developed to diagnose and treat our patients, which resulted in the first reported use of LESS to treat a subgroup of patients with PGAD/GPD secondary to lumbosacral annular tear–induced sacral radiculopathy. Another strength is the inclusion of patients with dysesthesia symptoms beyond unwanted genital arousal (ie, GPD). The use of this novel algorithm to carefully select candidates for the surgery led to 80% efficacy with minimal side effects. An additional strength is the development of a successful management strategy of these complex cases by involving a multidisciplinary team (spine surgeon, sexual medicine physician, sex therapist, physical therapist, and behavioral neuroscientist).

One limitation of this study is that the study cohort is small. In addition, while the main outcome measure (PGI-I) was obtained in all patients, not all patients were compliant in providing a PGI-I score every 3 months, despite being asked. Another limitation is that the PGI-I is not specific to PGAD/GPD; nevertheless, PGI-I is clinically relevant and has been widely used to measure the outcome of spine surgery.

Conclusion

In the present study, we provide evidence that there is a subgroup of patients with PGAD/GPD whose condition results from lumbosacral annular tear–induced sacral radiculopathy and that their condition can be ameliorated by LESS. By using our multidisciplinary step-care management algorithm (Figure 1), patients with PGAD/GPD who met the specific criteria were identified as having sacral radiculopathy and qualified for and were treated by LESS. This carefully selected subgroup of patients with PGAD/GPD was followed for ≥1 year post-LESS (average of 20 months). Surgical treatment of the underlying lumbosacral annular tear by LESS led to significant improvement in 80% of the patients as reported on the PGI-I. Consistent with the minimally invasive nature of LESS, all patients were discharged the same day and there were no surgical complications. Thus, for patients with PGAD/GPD resulting from lumbosacral annular tear–induced sacral radiculopathy, we provide evidence that LESS is a safe and effective treatment.

Acknowledgments

We thank April Patterson, PT, MSPT, for her knowledge and enthusiasm working with our patients and for her contributions to the writing of the pelvic floor physical therapy content.

References

- 1. Goldstein I, Komisaruk BR, Pukall CF, et al International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) review of epidemiology and pathophysiology, and a consensus nomenclature and process of care for the management of persistent genital arousal disorder/genito-pelvic dysesthesia (PGAD/GPD). J Sex Med. 2021;18(4):665–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.01.172.

- 2. Parish SJ, Cottler-Casanova S, Clayton AH, McCabe MP, Coleman E, Reed GM. The evolution of the female sexual disorder/dysfunction definitions, nomenclature, and classifications: a review of DSM, ICSM, ISSWSH, and ICD. Sex Med Rev. 2021;9(1):36–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2020.05.001.

- 3. Leiblum S, Seehuus M, Goldmeier D, Brown C. Psychological, medical, and pharmacological correlates of persistent genital arousal disorder. J Sex Med. 2007;4(5):1358–1366. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00575.x.

- 4. Pink L, Rancourt V, Gordon A. Persistent genital arousal in women with pelvic and genital pain. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014;36(4):324–330.

- 5. Jackowich R, Pink L, Gordon A, Pukall CF. Persistent genital arousal disorder: a review of its conceptualizations, potential origins, impact, and treatment. Sex Med Rev. 2016;4(4):329–342.

- 6. Dèttore D, Pagnini G. Persistent genital arousal disorder: a study on an Italian group of female university students. J Sex Marital Ther. 2021;47(1):60–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623x.2020.1804022.

- 7. Garvey LJ, West C, Latch N, Leiblum S, Goldmeier D. Report of spontaneous and persistent genital arousal in women attending a sexual health clinic. Int J STD AIDS. 2009;20(8):519–521. https://doi.org/10.1258/ijsa.2008.008492.

- 8. Jackowich R, Pukall CF. Prevalence of persistent genital arousal disorder in 2 North American samples. J Sex Med. 2020;17:2408–2416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.09.004.

- 9. Leiblum S, Brown C, Wan J, Rawlinson L. Persistent sexual arousal syndrome: a descriptive study. J Sex Med. 2005;2(3):331–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.20357.x.

- 10. Oaklander AL, Sharma S, Kessler K, Price BH. Persistent genital arousal disorder: a special sense neuropathy. Pain Rep. 2020;5(1):e801. https://doi.org/10.1097/pr9.0000000000000801.

- 11. Jackowich RA, Boyer SC, Bienias S, Chamberlain S, Pukall CF. Healthcare experiences of individuals with persistent genital arousal disorder/genito-pelvic dysesthesia. Sex Med. 2021;9(3):100335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esxm.2021.100335.

- 12. Klifto KM, Dellon AL. Persistent genital arousal disorder: review of pertinent peripheral nerves. Sex Med Rev. 2020;8(2):265–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2019.10.001.

- 13. Komisaruk BR, Goldstein I. Persistent genital arousal disorder: current conceptualizations and etiologic mechanisms. Current Sexual Health Reports. 2017;9(4):177–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-017-0122-5.

- 14. Leiblum S, Goldmeier D. Persistent genital arousal disorder in women: case reports of association with anti-depressant usage and withdrawal. J Sex Marit Ther. 2008;34(2):150–159.

- 15. Pukall CF, Jackowich R, Mooney K, Chamberlain SM. Genital sensations in persistent genital arousal disorder: a case for an overarching nosology of genitopelvic dysesthesias? Sex Med Rev. 2019;7(1):2–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2018.08.001.

- 16. Komisaruk B, Lee HJ. Prevalence of sacral spinal (Tarlov) cysts in persistent genital arousal disorder. J Sex Med. 2012;9:2047–2056.

- 17. Goldstein I, Komisaruk BR, Rubin RS, et al A novel collaborative protocol for successful management of penile pain mediated by radiculitis of sacral spinal nerve roots from Tarlov cysts. Sex Med. 2017;5(3):e203–e211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esxm.2017.04.001.

- 18. Feigenbaum F, Boone K. Persistent genital arousal disorder caused by spinal meningeal cysts in the sacrum: successful neurosurgical treatment. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(4):839–843. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000001060.

- 19. Liu KC, Yang SK, Ou BR, et al Using percutaneous endoscopic outside-in technique to treat selected patients with refractory discogenic low back pain. Pain Physician. 2019;22(2):187–198.

- 20. Manabe H, Yamashita K, Tezuka F, et al Thermal annuloplasty using percutaneous endoscopic discectomy for elite athletes with discogenic low back pain. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2019;59(2):48–53. https://doi.org/10.2176/nmc.oa.2018-0256.

- 21. Nakajima D, Yamashita K, Takeuchi M, et al Full-endoscopic spine surgery for discogenic low back pain with high-intensity zones and modic type 1 change in a professional baseball player. NMC Case Rep J. 2021;8(1):587–593. https://doi.org/10.2176/nmccrj.cr.2021-0038.

- 22. Namboothiri S, Gore S, Veerasekhar G. Treatment of low back pain by treating the annular high intensity zone (HIZ) lesions using percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic disc surgery. Int J Spine Surg. 2018;12(3):388–392. https://doi.org/10.14444/5045.

- 23. Nellensteijn J, Ostelo R, Bartels R, Peul W, van Royen B, van Tulder M. Transforaminal endoscopic surgery for symptomatic lumbar disc herniations: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(2):181–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-009-1155-x.

- 24. Zhang B, Liu S, Liu J, et al Transforaminal endoscopic discectomy versus conventional microdiscectomy for lumbar discherniation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2018;13(1):169. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-018-0868-0.

- 25. Lewandrowski KU. Incidence, management, and cost of complications after transforaminal endoscopic decompression surgery for lumbar foraminal and lateral recess stenosis: a value proposition for outpatient ambulatory surgery. Int J Spine Surg. 2019;13(1):53–67. https://doi.org/10.14444/6008.

- 26. Ruetten S, Komp M, Merk H, Godolias G. Full-endoscopic interlaminar and transforaminal lumbar discectomy versus conventional microsurgical technique: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(9):931–939. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816c8af7.

- 27. Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marit Ther. 2000;26(2):191–208.

- 28. Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49(6):822–830. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00238-0.

- 29. Derogatis L, Clayton A, Lewis-D’Agostino D, Wunderlich G, Fu Y. Validation of the female Sexual Distress Scale–Revised for assessing distress in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Med. 2008;5(2):357–364.

- 30. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396.

- 31. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x.

- 32. Padoa A, McLean L, Morin M, Vandyken C. “The overactive pelvic floor (OPF) and sexual dysfunction” part 1: pathophysiology of OPF and its impact on the sexual response. Sex Med Rev. 2021;9(1):64–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2020.02.002.

- 33. Padoa A, McLean L, Morin M, Vandyken C. The overactive pelvic floor (OPF) and sexual dysfunction. Part 2: evaluation and treatment of sexual dysfunction in OPF patients. Sex. Med Rev. 2021;9(1):76–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2020.04.002.

- 34. Dickson E, Higgins P, Sehgal R, et al Role of nerve block as a diagnostic tool in pudendal nerve entrapment. ANZ J Surg. 2019;89(6):695–699. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.15275.

- 35. Schellhas KP, Pollei SR, Gundry CR, Heithoff KB. Lumbar disc high-intensity zone: correlation of magnetic resonance imaging and discography. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21(1):79–86. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199601010-00018.

- 36. Aprill C, Bogduk N. High-intensity zone: a diagnostic sign of painful lumbar disc on magnetic resonance imaging. Br J Radiol. 1992;65(773):361–369. https://doi.org/10.1259/0007-1285-65-773-361.

- 37. Schaufele MK, Hatch L, Jones W. Interlaminar versus transforaminal epidural injections for the treatment of symptomatic lumbar intervertebral disc herniations. Pain Physician. 2006;9(4):361–366.

- 38. Rigoard P, Ounajim A, Goudman L, et al A novel multi-dimensional clinical response index dedicated to improving global assessment of pain in patients with persistent spinal pain syndrome after spinal surgery, based on a real-life prospective multicentric study (PREDIBACK) and machine learning techniques. J Clin Med. 2021;10(21):4910. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10214910.

- 39. Busner J, Targum SD. The clinical global impressions scale: applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007;4(7):28–37.

- 40. Guy W. Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) Scale, Modified. In: , ed. Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- 41. Tsou PM, Alan Yeung C, Yeung AT. Posterolateral transforaminal selective endoscopic discectomy and thermal annuloplasty for chronic lumbar discogenic pain: a minimal access visualized intradiscal surgical procedure. Spine J. 2004;4(5):564–573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2004.01.014.

- 42. Kim CW, Phillips F. The history of endoscopic posterior lumbar surgery. Int J Spine Surg. 2021;15(suppl 3):S6–S10. https://doi.org/10.14444/8159.

- 43. Ahn Y. Endoscopic spine discectomy: indications and outcomes. Int Orthop. 2019;43(4):909–916. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-018-04283-w.

- 44. Bellut D, Burkhardt JK, Schultze D, Ginsberg HJ, Regli L, Sarnthein J. Validating a therapy-oriented complication grading system in lumbar spine surgery: a prospective population-based study. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):11752. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12038-7.

- 45. Samuelly-Leichtag G, Eisenberg E, Zohar Y, et al Mechanism underlying painful radiculopathy in patients with lumbar disc herniation. Eur J Pain. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1947.

- 46. Inoue N, Espinoza Orías AA. Biomechanics of intervertebral disk degeneration. Orthop Clin North Am. 2011;42(4):487–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocl.2011.07.001.

- 47. Camino Willhuber G, Elizondo C, Slullitel P. Analysis of postoperative complications in spinal surgery, hospital length of stay, and unplanned readmission: application of Dindo-Clavien classification to spine surgery. Global Spine J. 2019;9(3):279–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568218792053.

- 48. Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, et al The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250(2):187–196. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2.

- 49. Rosenbaum T. Physical therapy treatment of persistent genital arousal disorder during pregnancy: a case report. J Sex Med. 2010;7(3):1306–1310.

- 50. Gaines N, Odom BD, Killinger KA, Peters KM. Pudendal neuromodulation as a treatment for persistent genital arousal disorder—a case series. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018;24(4):e1–e5. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000000435.

- 51. Peters K, Killinger KA, Jaeger C, Chen C. Pilot study exploring chronic pudendal neuromodulation as a treatment option for pain associated with pudendal neuralgia. Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 2015;7(3):138–142.

- 52. Thorne C, Stuckey B. Pelvic congestion syndrome presenting as persistent genital arousal: a case report. J Sex Med. 2008;5(2):504–508.

- 53. Kruger THC. Can pharmacotherapy help persistent genital arousal disorder? Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2018;19(15):1705–1709. https://doi.org/10.1080/14656566.2018.1525359.

- 54. Philippsohn S, Kruger TH. Persistent genital arousal disorder: successful treatment with duloxetine and pregabalin in two cases. J Sex Med. 2012;9(1):213–217.

- 55. Korda J, Pfaus JG, Kellner CH, Goldstein I. Persistent genital arousal disorder (PGAD): case report of long-term symptomatic management with electroconvulsive therapy. J Sex Med. 2009;6(10):2901–2909.

- 56. Andrade P, Hoogland G, Garcia MA, Steinbusch HW, Daemen MA, Visser-Vandewalle V. Elevated IL-1β and IL-6 levels in lumbar herniated discs in patients with sciatic pain. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(4):714–720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-012-2502-x.

- 57. Yamashita M, Ohtori S, Koshi T, et al Tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the nucleus pulposus mediates radicular pain, but not increase of inflammatory peptide, associated with nerve damage in mice. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(17):1836–1842. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817bab2a.

- 58. Korse N, Jacobs WC, Elzevier HW, Vleggeert-Lankamp CL. Complaints of micturition, defecation and sexual function in cauda equina syndrome due to lumbar disk herniation: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2013;22:1019–1029.

- 59. Lew-Starowicz M, Lewczuk K, Nowakowska I, Kraus S, Gola M. Compulsive sexual behavior and dysregulation of emotion. Sex Med Rev. 2020;8(2):191–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2019.10.003.

- 60. Leiblum S, Seehuus M, Brown C. Persistent genital arousal: disordered or normative aspect of female sexual response? J Sex Med. 2007;4(3):680–689. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00495.x.

- 61. Carvalho J, Veríssimo A, Nobre PJ. Cognitive and emotional determinants characterizing women with persistent genital arousal disorder. J Sex Med. 2013;10(6):1549–1558. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12122.

- 62. Goldstein I. Persistent genital arousal disorder-update on the monster sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2013;10(10):2357–2358. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12314.

- 63. Parish S, Brody B. Persistent genital arousal disorder associated with depression and suicidality in two psychiatric inpatients. J Sex Med. 2019;16:S27.

- 64. Leiblum SR, Seehuus M. FSFI scores of women with persistent genital arousal disorder compared with published scores of women with female sexual arousal disorder and healthy controls. J Sex Med. 2009;6(2):469–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01077.x.

- 65. Waldinger M, Venema PL, van Gils APG, Schutter EMJ, Schweitzer DH. Restless genital syndrome before and after clitoridectomy for spontaneous orgasms: a case report. J Sex Med. 2009;7:1029–1034.

- 66. Brinjikji W, Luetmer PH, Comstock B, et al Systematic literature review of imaging features of spinal degeneration in asymptomatic populations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36(4):811–816. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A4173.

- 67. Pukall C, Goldmeier D. Persistent genital arousal disorder. In: KSK H, Binik YM eds. Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy. Guilford Press; 2020: 488–503.

- 68. Elkins G, Ramsey D, Yu Y. Hypnotherapy for persistent genital arousal disorder: a case study. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2014;62(2):215–223.

- 69. Pukall C, Bergeron S. Psychological management of provoked vestibulodynia. In: Goldstein I, Clayton AH, Goldstein AT, Kim NN, Kingsberg SA eds. Textbook of Female Sexual Function and Dysfunction: Diagnosis. Wiley; 2018: 281–294.

- 70. Horvath AO, Luborsky L. The role of the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61(4):561–573. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.61.4.561.

- 71. Whiston S, Sexton TL. An overview of psychotherapy outcome research: implications for practice. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 1993;24(1):43–51.

- 72. Ogles B, Anderson T, Lunnen KM. The contribution of models and techniques to therapeutic efficacy: contradictions between professional trends and clinical research. In: Hubble MA, Duncan BL, Miller SD eds. The Heart and Soul of Change: What Works in Therapy. American Psychological Association; 1999: 201–225.

- 73. Wampold B. The Great Psychotherapy Debate: Models, Methods, and Findings. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2001.

- 74. Lambert M. The efficacy and effectiveness of psychotherapy. In: Lambert M ed. Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change. 5th ed. Wiley; 2004: 139–193.

- 75. Arnd-Caddigan M. The therapeutic alliance: implications for therapeutic process and therapeutic goals. J Contemp Psychother. 2012;42(2):77–85.

- 76. Cataldo L, Ramsey K. Social media’s impact on PGAD patients. J Sex Med. 2016;13:S256.

- 77. Poirier E, Cataldo LM. The complexities of persistent genital arousal disorder (PGAD). J Sex Med. 2017;14:e368.

- 78. Stein A, Sauder SK, Reale J. The role of physical therapy in sexual health in men and women: evaluation and treatment. Sex Med Rev. 2019;7(1):46–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2018.09.003.

- 79. Verbeek M, Hayward L. Pelvic floor dysfunction and its effect on quality of sexual life. Sex Med Rev. 2019;7(4):559–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2019.05.007.

- 80. Bradley MH, Rawlins A, Brinker CA. Physical therapy treatment of pelvic pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2017;28(3):589–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2017.03.009.

- 81. George SE, Clinton SC, Borello-France DF. Physical therapy management of female chronic pelvic pain: anatomic considerations. Clin Anat. 2013;26(1):77–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.22187.