ChatGPT is an artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot that creates conversational dialogue with the user. It has been used in clinical care and medical education. Its potential role in diabetes education for patients has been explored, but safety concerns have been raised., There has been much interest in how AI can have a role in Travel Medicine in teaching, providing more personalized advice, and aid in the pre-travel consultation.,

Pre-travel consultation and advice is often provided by primary care providers and travel medicine specialists. It is an effective tool that can reduce the morbidity of traveller’s diarrhoea and improve health-seeking behaviour, although its uptake has been dismal., With increasing accessibility and widespread use of ChatGPT, we anticipate that travellers may turn to chatbots as a convenient option to seek pre-travel advice. As such, we aimed to evaluate pre-travel advice provided by ChatGPT.

We instructed ChatGPT to give pre-travel advice and subsequently provided the application with a series of commonly-asked questions, pertaining to general travel queries (such as food and water safety, sexual health, traveller’s diarrhoea), vaccinations and malaria prophylaxis. The accuracy and appropriateness of the responses were then compared against recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control Yellow Book 2024 and Shoreland Travax.

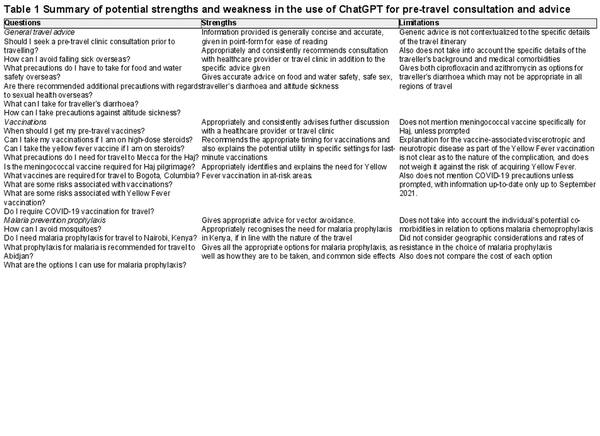

ChatGPT could answer all the questions provided. The answers given were concise and often in point form, making them easy to read and understand (Supplementary Table S1). We evaluated the strengths and limitations of the responses provided by ChatGPT in the specific areas of pre-travel advice (Table 1) from the perspective of experienced and certified travel medicine specialists.

In the first area of general travel queries, ChatGPT answered the questions accurately, although the advice provided was generic and not contextualized to the individual’s specific travel itinerary and medical co-morbidities. For example, a patient with a history of splenectomy would be at a significantly elevated risk of severe malaria, a vital consideration to highlight in the pre-travel consultation. ChatGPT also suggested ciprofloxacin or azithromycin for traveller’s diarrhoea. In most geographic areas, quinolone resistance is high and azithromycin may be the better option. The advice provided while logical, like choosing restaurants with ‘good hygiene practices’, may not necessarily be practical, as travellers cannot feasibly inspect a restaurant’s hygiene practices prior to making dining choices.

ChatGPT accurately gave advice for altitude sickness and the necessary precautions but similarly did not explain potential adverse effects of acetazolamide. Furthermore, while ChatGPT mentions the Andes and Himalayas, it fails to specifically mention Kilimanjaro as an important location for altitude-related fatality. In contrast, a human provider would have the ability to probe with follow-up questions and thus give more specific and detailed travel advice.

ChatGPT was able to provide an exhaustive list of important immunisations required for specific areas of travel, including the timing of these vaccines prior to travel (Supplementary Table S1 available as Supplementary data at JTM online, Table 1). For example, Bogota, Columbia was appropriately identified as an area not at high risk for yellow fever transmission, but that vaccination may still be recommended for travel to other parts of Columbia. Importantly, ChatGPT failed to emphasize that some vaccinations are required, such as the meningococcal vaccination for pilgrims going on Hajj. ChatGPT also does not readily take into account an individual’s prior immunization status and medical comorbidities in its recommendation. However, if prompted directly, it is able to provide appropriate advice. For example, when asked about yellow fever vaccination (which is a live vaccine) in an individual on steroids, ChatGPT appropriately raises concern, and directs the traveller to a healthcare provider for assessment.

Perhaps because recent outbreaks such as COVID-19 and human Mpox are not classically part of pre-travel advice, these vaccinations are also not specifically addressed, unless directly asked. ChatGPT also specifies in its reply that the information provided on COVID-19 is from September 2021, and does not include up-to-date recommendations.

Finally, with regards to malaria prevention, ChatGPT appropriately identifies geographical areas at risk for malaria transmission (we tested this on both Nairobi and Abidjan), provides comprehensive details on aspects of vector avoidance for travellers and lists options for malaria chemoprophylaxis (Table 1, Supplemental Table S1 available as Supplementary data at JTM online). It does not take into account an individual’s medical co-morbidities, or the geographic area of travel, which may influence choice of prophylaxis. Costs of various drugs are also often a very important consideration for travellers but are not addressed by ChatGPT. ChatGPT also fails to consider the specific nature of a patient’s travel. For example, a traveller who is largely staying indoors, and within the city centre of Nairobi may safely choose to decline malaria chemoprophylaxis.

The accessibility of ChatGPT at any time makes it easy for the layperson to use, and may improve the uptake of pre-travel advice and consultation. The advice provided may be more comprehensive and exhaustive than a human provider. For example, in preventing malaria, an option to reduce risk may be to choose to travel in the dry season instead of wet season. ChatGPT recognizes this and provides this advice, but a human provider may have neglected to consider that changing the date of travel may be an option.

There are important limitations to our findings and study design. It was designed as a conversation to explore commonly asked questions. Therefore, it was not an exhaustive evaluation of all potentially erroneous information that ChatGPT could provide. Furthermore, we only included a single AI chatbot, with no replication of experimental queries. ChatGPT also was not able to provide verifiable sources from which the information had been obtained, thus making it difficult for travellers to independently verify the accuracy of the responses.

Overall, the use of AI chatbots for pre-travel advice may be vital and complementary to the physical consultation. ChatGPT consistently highlights the importance of seeking advice from a healthcare provider prior to travel. Unlike a human provider, ChatGPT is accessible at any time, and provides comprehensive answers. It may at times lack specificity in contextualizing advice to the individual traveller and circumstance; however, a human healthcare provider could step in to fill that gap.

Acknowledgements

N/A

References

- 1. Adamopoulou E, Moussiades L. An Overview of Chatbot Technology. In: Maglogiannis I, Iliadis L, Pimenidis E (eds). Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations. Vol 584. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology. Greece: Springer International Publishing, 2020; 584, pp. 373–83.

- 2. Khan RA, Jawaid M, Khan AR, Sajjad M. ChatGPT - reshaping medical education and clinical management. Pak J Med Sci2023; 39:605–7.

- 3. Sharma S, Pajai S, Prasad R, et al A critical review of ChatGPT as a potential substitute for diabetes educators. Cureus2023; 15:e38380. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.38380.

- 4. Sng GGR, Tung JYM, Lim DYZ, Bee YM. Potential and pitfalls of ChatGPT and natural-language artificial intelligence models for diabetes education. Diabetes Care2023; 46:e103–5.

- 5. Kwok KO, Wei WI, Tsoi MTF, et al How can we transform travel medicine by leveraging on AI-powered search engines? J Travel Med 2023; 30:taad058.

- 6. Flaherty GT, Piyaphanee W. Predicting the natural history of artificial intelligence in travel medicine. J Travel Med2023; 30:taac113. https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taac113.

- 7. Gherardin T. The pre-travel consultation - an overview. Aust Fam Physician2007; 36:300–3.

- 8. Tan EM, St. Sauver JL, Sia IG. Impact of pre-travel consultation on clinical management and outcomes of travelers’ diarrhea: a retrospective cohort study. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines2018; 4:16.

- 9. Heywood AE, Watkins RE, Iamsirithaworn S, Nilvarangkul K, MacIntyre CR. A cross-sectional study of pre-travel health-seeking practices among travelers departing Sydney and Bangkok airports. BMC Public Health2012; 12:321.

- 10. Nemhauser JB. CDC Yellow Book 2024: Health Information for International Travel. New York, NY, United States: Oxford University Press, 2023.