INTRODUCTION

Commonly referred to as “ringing in the ears,” tinnitus is the perception of sound that occurs in the absence of external sound., It can be constant or intermittent, loud or soft, noise or tonal, and is often accompanied by hearing loss. Tinnitus is a symptom of dysfunction in the auditory system that can result from hazardous noise, ototoxic medications and chemicals, as well as a number of health-related conditions. Hazardous noise, in particular, is a widespread occupational exposure for military service members. The post-9/11 conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan saw years of sustained combat coupled with an unparalleled use of blast weaponry.

Prevalence estimates of tinnitus vary widely in the literature, because of differences in diagnostic criteria, study questions, and reporting and analysis of results. Previous studies in military populations have reported that the proportions of service members and veterans with tinnitus ranged from 6% to 54%., A study from the Expeditionary Medical Encounter Database (EMED) found that 19% of service members who sustained blast-related injuries during overseas contingency operations in Iraq and Afghanistan were diagnosed with tinnitus in-theater. Tinnitus can also co-occur with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and concussion, two other common wartime conditions., The overall burden of tinnitus is significant, as it ranks number one in service-connected disability among veterans who received compensation benefits, affecting 1,971,201 veterans in Fiscal Year 2018 alone.

Self-rated health is a valid and widely used measure that assesses health across multiple dimensions, including physical, psychological, social, and cognitive functioning and has been found to be a predictor of mortality among young adults. A Swedish study among a working age population found that more than half of those reporting tinnitus and other hearing complaints rated their health as poor. Wang et al. similarly found that presence of tinnitus was associated with lower self-rated health among older Australian adults. Studies among military and veteran populations have examined the associations between self-rated health and concussion, PTSD, and health care utilization, but none have specifically addressed tinnitus.

The present study aimed to: (1) describe the prevalence of self-reported tinnitus by injury mechanism at two different time points following deployment-related injury and (2) determine the association between tinnitus and self-rated health after adjusting for combat exposure, concussion, PTSD, and other covariates.

METHODS

Study Sample

The Expeditionary Medical Encounter Database (EMED) was used to identify military personnel who sustained an injury during combat deployment in Iraq and who completed a Post-Deployment Health Assessment (PDHA) and Post-Deployment Health Reassessment (PDHRA). The EMED is a deployment health database that contains clinical encounters of military service members while deployed. All information on the EMED clinical record was verified by certified nurse coders. For medical screening purposes, the PDHA is administered to military personnel within 30 days of their deployment end date. This is followed up with the PDHRA after allowing time for reintegration home. Both of these assessments have been used in military medical research. For inclusion, both the PDHA and PDHRA had to be completed within 1 year post-injury, and the minimum amount of time between the two assessments was 30 days. The study sample included 1,026 military personnel injured between March 2004 and April 2008. This study period was selected based on the availability of PDHA data at the time of the analysis. All study procedures received approval through the Institutional Review Board at Naval Health Research Center, San Diego, California.

Measures

Demographic and Service-Related Characteristics

Demographic and service-related variables at the time of injury were extracted from the Defense Manpower Data Center and included sex, age at time of injury, military rank, and service branch.

Injury-Related Characteristics

Injuries were classified by mechanism and severity using EMED data. Circumstances and tactical information surrounding the injury event were abstracted from the EMED clinical record, and injuries were categorized by primary mechanism as: battle blast, battle nonblast, and nonbattle. Injury severity was measured using the Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) and Injury Severity Score (ISS)., The study was limited to those with mild (ISS 1–3) and moderate (ISS 4–8) injuries.

Tinnitus

Presence or absence of tinnitus is queried on both the PDHA and PDHRA, along with a list of other symptoms. Respondents were asked to indicate whether they were currently experiencing “ringing in the ears.”

Combat Exposure

The PDHA asks three yes/no questions to assess level of combat exposure. Specific questions ask whether the respondent: (1) saw anyone wounded, killed, or dead; (2) if they discharged their weapon in direct combat; and (3) if they felt in great danger of being killed. The number of affirmative responses was summed and categorized into 0–1, 2, and 3 reported combat exposures.

Concussion

EMED data provided comprehensive information characterizing each injury using ICD-9 codes. Concussion was defined as presence of a provider-diagnosed concussion (ICD-9 850).

PTSD Symptoms

Both the PDHA and PDHRA contain the Primary Care PTSD Screen, which is a validated four-item assessment tool for PTSD., It asks whether the respondent ever had an experience during their deployment that resulted in the following symptoms: (1) had nightmares about it or thought about it when you did not want to; (2) tried hard not to think about it or went out of your way to avoid situations that remind you of it; (3) were constantly on guard, watchful or easily startled; and (4) felt numb or detached from others, activities or your surroundings. Answering “yes” to at least two of the four questions was considered a screen positive for PTSD symptoms.

Self-Rated Health

Self-rated health is assessed on the PDHA and PDHRA as a five-item scale with the options of excellent, very good, good, fair and poor. The variable was further dichotomized per previous literature into good-excellent and fair-poor.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data management and statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Descriptive statistics were calculated for the entire study sample. The prevalence of tinnitus by injury mechanism, and PTSD and self-rated health by tinnitus status were shown separately for the PDHA and PDHRA. Chi-square statistics were used to test for differences. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to examine the relationship between tinnitus and self-rated health on the PDHA and PDHRA after adjusting for selected covariates. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test, which evaluates model fit by comparing observed values versus expected, was used to assess the models for the goodness of fit with an alpha level of 0.10 (good fit indicated by P > 0.10). For the separate PDHA and PDHRA analyses, the PTSD, tinnitus, and self-rated health variables were measured on both assessments.

RESULTS

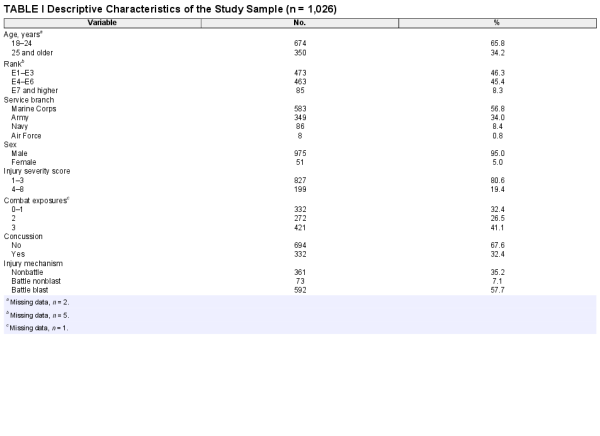

Descriptive statistics for the study sample are presented in Table I. A majority were 18–24 years old (65.8%), enlisted ranks E1–E6 (91.7%), Marines (56.8%), and male (95.0%). Most individuals had an ISS of 1–3 (80.6%) and were categorized as battle blast (57.7%), followed by nonbattle (35.2%), and battle nonblast (7.1%). The most prevalent causes of injury for battle blast, nonbattle, and battle nonblast were improvised explosive devices, aggravated range of motion, and gunshot wounds, respectively. Nearly one in three individuals sustained a concussion (32.4%). Average time was 89.3 days (SD = 55.1) from injury to completion of PDHA and 166.2 days (SD = 55.1) between PDHA and PDHRA.

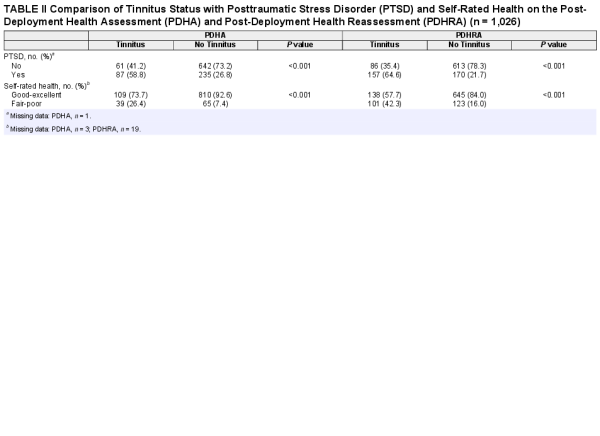

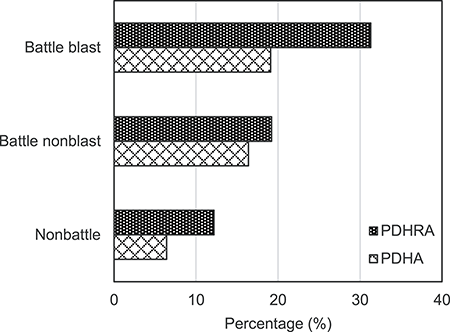

The prevalence of tinnitus by injury mechanism is shown in Figure 1. Across all mechanisms, self-reported tinnitus was higher on the PDHRA than the PDHA. The highest prevalence of tinnitus was among individuals with battle blast injuries at 19.1% and 31.3% on the PDHA and PDHRA, respectively, followed by battle nonblast (PDHA 16.4%, PDHRA 19.2%) and nonbattle (PDHA 6.4%, PDHRA 12.2%), and these differences were statistically significant (P < 0.001). Table II further describes tinnitus on the PDHA and PDHRA by PTSD and self-rated health. Compared to those without tinnitus, individuals with tinnitus had significantly higher rates of PTSD on both the PDHA (58.8% vs. 26.8%, P < 0.001) and PDHRA (64.6% vs. 21.7%; P < 0.001), and greater endorsement of fair-poor health on the PDHA (26.4% vs. 7.4%; P < 0.001) and PDHRA (42.3% vs. 16.0%; P < 0.001).

FIGURE 1

Prevalence of Tinnitus by Injury Mechanism on Post-Deployment Health Assessment (PDHA) and Post-Deployment Health Reassessment (PDHRA) (n = 1,026).

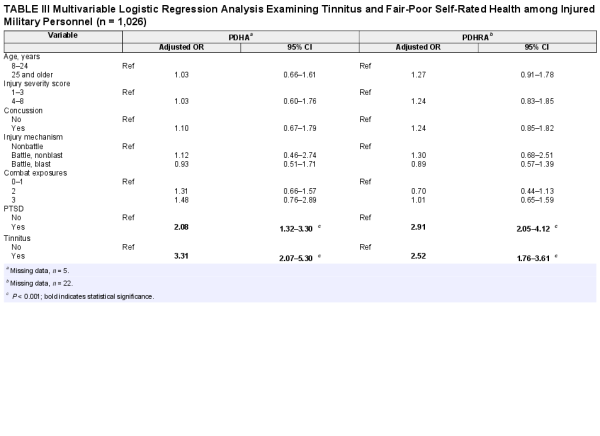

Separate multivariable logistic regression models were run for the PDHA and PDHRA, and results are shown in Table III. The only covariates associated with increased odds of endorsing fair-poor health were tinnitus and PTSD. Military personnel who reported tinnitus, relative to those who did not, had greater odds of endorsing fair-poor health on the PDHA (OR = 3.31, 95% CI = 2.07–5.30, P < 0.001) and PDHRA (OR = 2.52, 95% CI = 1.76–3.61, P < 0.001). Higher odds of fair-poor self-rated health were also found for those who screened positive for PTSD, compared with those who did not, on the PDHA (OR 2.08; 95% CI 1.32–3.30, P < 0.001) and PDHRA (OR = 2.91, 95% CI = 2.05–4.12, P < 0.001). Hosmer–Lemeshow tests indicated a good fit for both models.

DISCUSSION

Tinnitus prevalence and self-rated health were examined in a sample of mostly young, male, military personnel with deployment-related injuries. While one study estimated the rate of tinnitus in the general population as 1% for young adults below the age of 45, the present findings revealed a tinnitus rate up to 30-times higher in post-deployment personnel, which even exceeded estimates for adults over age 65., This reflects the overall burden of tinnitus disability, which appears to be pervasive throughout the military. Furthermore, reporting tinnitus was negatively associated with self-rated health, highlighting the potential quality of life problems faced by veterans with this type of hearing impairment. Focus of tinnitus management should be on early identification and intervention. Routine screening for tinnitus, particularly following blast injury, will help target mitigation efforts aimed at improving subjective and objective health status.

The prevalence of tinnitus was highest in those with battle blast injuries, which is not surprising given the scientific literature on auditory damage caused by this injury mechanism. Tsao et al. found that blast injury predicted tinnitus symptoms among U.S. Marines, and two studies of civilian bombings found post-injury tinnitus rates of 68% and 80%, respectively., The rate of tinnitus among battle blast injuries on the PDHA was 19.1%, which was consistent with a previous study reporting the same rate of tinnitus immediately following blast injury. The increase in tinnitus to 31.3% on the PDHRA was interesting, particularly since tinnitus may be expected to resolve with time. This temporal difference may be attributable to other risk factors for tinnitus encountered in the period between the PDHA and PDHRA, such as smoking and recreational/occupational noise. It is also possible that military personnel may become more cognizant of experiencing tinnitus symptoms upon returning home from deployment where living conditions might be quieter and less stressful. Furthermore, a reporting bias cannot be ruled out, as military personnel may be more likely to report tinnitus after deployment because of reduced stigma of endorsement. For example, one study found that military personnel were more likely to report mental health symptoms on the PDHRA than the PDHA. The PDHA is often completed before returning home, and service members may feel that reporting adverse symptoms could impact their redeployment timeline. Future studies should examine the timing of tinnitus assessment and whether this influences prevalence estimates. Given that blast injuries are a hallmark of modern warfare, it is essential to define the prevalence and trajectory of tinnitus in relation to this injury type.

Tinnitus was associated with greater odds of fair or poor self-rated health, which is consistent with a pair of civilian studies., These findings support previous research that suggests tinnitus and associated comorbidities, including psychological disorders such as PTSD, may have a significant and multifaceted negative impact on the health of service members. Future studies on other comorbidities of tinnitus, such as insomnia and dizziness, are needed to fully assess the relationship with self-rated health, and to examine the impact on job performance and quality of life. Weidt et al. found that tinnitus severity and subjective loudness was associated with lower quality of life and higher depression scores. Validated instruments exist that could further define the relationship between tinnitus and self-rated health. A tinnitus questionnaire such as the Tinnitus Functional Index or the Mini-Tinnitus Questionnaire should be administered for those with suspected tinnitus, and could augment and provide more granularity than the dichotomous (ie, yes/no) response from the PDHA and PDHRA., It would also be helpful to examine how tinnitus treatments affect self-rated health, as hearing aids, for example, have shown promise in treating military veterans.

The relationship between tinnitus and self-rated health was independent of PTSD, though the high rate of comorbidity between tinnitus and PTSD was a secondary finding of interest. A growing body of literature suggests a link between tinnitus and PTSD, with one condition possibly exacerbating the other.,,, Theories on etiology have ranged from shared risk factors to a neuro-biological connection. One recent military study found that PTSD symptoms more than doubled the likelihood of tinnitus progression. In addition, PTSD symptoms are negatively correlated with self-rated health. Future studies examining tinnitus and quality of life measures among military personnel need to account for PTSD.

Clinical management of tinnitus calls for a multidisciplinary approach. Mental health providers and audiologists treating injured military personnel should be aware of tinnitus and its psychological comorbidities and should make referrals as necessary. It is possible that successful treatment of tinnitus symptoms could dually impact comorbid psychological disorders. Tinnitus is also a concern for occupational health professionals. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health states that tinnitus can potentially increase the risk for workplace accidents by disrupting and degrading sleep, concentration, alertness, and performance. Cantley et al. found that individuals with tinnitus and high-frequency hearing loss had a 25% increased risk for occupational injury. Operational risk assessment should be conducted on workers suffering from tinnitus, and mitigation strategies should be implemented to prevent occupational mishaps and injuries.

This study had several strengths. Using provider records with accurate dates of injury allowed for tinnitus ascertainment restricted to 1 year postinjury. The PDHA and PDHRA made use of standard health questionnaires given at two separate time points to assess tinnitus, PTSD, and self-rated health in a large sample of injured military personnel. Multivariable modeling was further able to adjust for potential confounding effects of combat exposure, injury severity, and concussion. There were also limitations. There is no universal definition or standardized classification system for tinnitus. Although tinnitus includes “ringing in the ears,” this is one of many ways to characterize it, so the true burden may be underestimated. Temporality could not be established, as tinnitus that may have existed prior to deployment or military service was not ascertained. Furthermore, additional granularity on tinnitus symptoms that may have influenced self-rated health, such as laterality (eg, left ear, right ear), severity, frequency, duration, and annoyance level, was not available. It was also not possible to determine whether endorsement of symptoms may have been influenced by a secondary gain, such as the potential for disability benefits.

CONCLUSIONS

To our knowledge, this is the first study to link tinnitus to poorer self-rated health among injured military personnel. As tinnitus continues to a leading cause of disability among veterans, clinical management should be multidisciplinary and include not just the audiologist, but other specialties related to tinnitus comorbidities, such as PTSD. The use of standardized health assessments following military deployment remains a valuable tool for identifying vulnerable populations and should be augmented by more focused screening for tinnitus among high-risk personnel, particularly those exposed to or injured by a blast. Future military conflicts are likely to see a similar burden of blast injuries and associated tinnitus, and research should focus on strategies to improve long-term quality of life for these wounded veterans.

I am a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of my official duties. Title 17, U.S.C. §105 provides that copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the U.S. Government. Title 17, U.S.C. §101 defines a U.S. Government work as work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person’s official duties. Report No. 19-76 was supported by the U.S. Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery under work unit no. 60808. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the U.S. Government. The study protocol was approved by the Naval Health Research Center Institutional Review Board in compliance with all applicable Federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects. Research data were derived from an approved Naval Health Research Center, Institutional Review Board protocol number NHRC.2003.0025.

References

- 1. Jastreboff PJ: Phantom auditory perception (tinnitus): mechanisms of generation and perception. Neurosci Res1990; 8: 221–54.

- 2. Han BI, Lee HW, Kim TY, Lim JS, Shin KS: Tinnitus: characteristics, causes, mechanisms and treatments. J Clin Neurol2009; 5: 1–19.

- 3.

- 4. Theodoroff SM, Lewis MS, Folmer RL, Henry JA, Carlson KF: Hearing impairment and tinnitus: prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes in US service members and veterans deployed to the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Epidemiol Rev2015; 37: 71–85.

- 5. Greer N, Sayer N, Kramer M, Koeller E, Velasquez T. Prevalence and Epidemiology of Combat Blast Injuries from the Military Cohort 2001–2014. Washington, DC, Department of Veterans Affairs, 2016.

- 6. Cave KM, Cornish EM, Chandler DW: Blast injury of the ear: clinical update from the global war on terror. Mil Med2007; 172(7): 726–30.

- 7. Dougherty AL, MacGregor AJ, Han PP, Viirre E, Heltemes KJ, Galarneau MR: Blast-related ear injuries among U.S. military personnel. J Rehabil Res Dev2013; 50(6): 893–904.

- 8. Helfer TM, Jordan NN, Lee RB: Postdeployment hearing loss in U.S. Army soldiers seen at audiology clinics from April 1, 2003, through March 31 205. Am J Audiol2004; 14(2): 161–8.

- 9. Helling ER: Otologic blast injuries due to the Kenya embassy bombing. Mil Med2004; 169(11): 872–6.

- 10. Muhr P, Rosenhall U: The influence of military service on auditory health and the efficacy of a hearing conservation program. Noise Health2011; 13(53): 320–7.

- 11. Ritenour AE, Wickley A, Ritenour JS, et al: Tympanic membrane perforation and hearing loss from blast overpressure in operation enduring freedom and operation Iraqi freedom wounded. J Trauma2008; 64(2 Suppl): S174–8.

- 12. Swan AA, Nelson JT, Swiger B, et al: Prevalence of hearing loss and tinnitus in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans: a chronic effects of neurotrauma consortium study. Hear Res2017; 349: 4–12.

- 13. Fagelson MA: The association between tinnitus and posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Audiol2007; 16(2): 107–17.

- 14. Kreuzer PM, Landgrebe M, Vielsmeier V, Kleinjung T, De Ridder D, Langguth B: Trauma-associated tinnitus. J Head Trauma Rehabil2014; 29: 432–42.

- 15.

- 16. Haddock CK, Poston WSC, Pyle SA, et al: The validity of self-rated health as a measure of health status among young military personnel: evidence from a cross-sectional survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes2006; 4: 57.

- 17. Singh-Manoux A, Martikainen P, Ferrie J, et al: What does self-rated health measure? Results from the British Whitehall II and French Gazel cohort studies. J Epidemiol Community Health2006; 60: 364–72.

- 18. Larsson D, Hemmingsson T, Allebeck P, Lundberg I: Self-rated health and mortality among young men: what is the relation and how may it be explained?Scand J Public Health2002; 30: 259–66.

- 19. Singh-Manoux A, Gueguen A, Martikainen P, et al: Self-rated health and mortality: short- and long-term associations in the Whitehall II study. Psychosom Med2007; 69: 138–43.

- 20. Hasson D, Theorell T, Wallén MB, Leineweber C, Canlon B: Stress and prevalence of hearing problems in the Swedish working population. BMC Public Health2011; 11: 130.

- 21. Wang JJ, Smith W, Cumming RG, Mitchell P: Variables determining perceived global health ranks: findings from a population-based study. Ann Acad Med Singap2006; 35: 190–7.

- 22. Heltemes KJ, Holbrook TL, MacGregor AJ, Galarneau MR: Blast-related mild traumatic brain injury is associated with a decline in self-rated health amongst US military personnel. Injury2012; 43: 1990–5.

- 23. Benyamini Y, Ein-Dor T, Ginzburg K, Solomon Z: Trajectories of self-rated health among veterans: a latent growth curve analysis of the impact of posttraumatic symptoms. Psychosom Med2009; 71: 345–52.

- 24. Trump DH: Self-rated health and health care utilization after military deployments. Mil Med2006; 171: 662–8.

- 25. Galarneau MR, Hancock WC, Konoske P, et al: The navy-marine corps combat trauma registry. Mil Med2006; 171: 691–7.

- 26. Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS: Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA2006; 295(9): 1023–32.

- 27. Milliken CS, Auchterlonie JL, Hoge CW: Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq war. JAMA2007; 298(18): 2141–8.

- 28. MacGregor AJ, Dougherty AL, Tang JJ, Galarneau MR: Postconcussive symptom reporting among US combat veterans with mild traumatic brain injury from operation Iraqi freedom. J Head Trauma Rehabil2013; 28(1): 59–67.

- 29. Baker SP, O'Neill B, Haddon W Jr, Long WB: The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma1974; 14: 187–96.

- 30. Copes WS, Champion HR, Sacco WJ, Lawnick MM, Keast SL, Bain LW: The injury severity score revisited. J Trauma1988; 28: 69–77.

- 31. Commission on Professional Hospital Activities. International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification. Ann Arbor, MI, Edwards Brothers, 1977.

- 32. Ommaya AK, Ommaya AK, Dannenberg AL, Salazar AM: Causation, incidence, and costs of traumatic brain injury in the U.S. military medical system. J Trauma1996; 40(2): 211–7.

- 33. Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, et al: The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Prim Care Psychiatry2004; 9: 9–14.

- 34. Bliese PD, Wright KM, Adler AB, Cabrera O, Castro CA, Hoge CW: Validating the primary care posttraumatic stress disorder screen and the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist with soldiers returning from combat. J Consult Clin Psychol2008; 76(2): 272–81.

- 35. Manor O, Matthews S, Power C: Dichotomous or categorical response? Analysing self-rated health and lifetime social class. Int J Epidemiol2000; 29(1): 149–57.

- 36. Adams PF, Hendershot GE, Marano MACenters for Disease Control and Prevention/National Center for Health Statistics: Current estimates from the national health interview survey, 1996. Vital Heaalth Stat 101999; 200: 1–203.

- 37. Hiller W, Goebel G: Rapid assessment of tinnitus-related psychological distress using the mini-TQ. Int J Audiol2004; 43(10): 600–4.

- 38. Alamgir H, Turner CA, Wong NJ, et al: The impact of hearing impairment and noise-induced hearing injury on quality of life in the active-duty military population: challenges to the study of this issue. Mil Med Res2016; 3: 11.

- 39. Hirsch FG: Effects of overpressure on the ear—a review. Ann N Y Acad Sci1968; 152(1): 147–62.

- 40. Lew HL, Jerger JF, Guillory SB, Henry JA: Auditory dysfunction in traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Res Dev2007; 44(7): 921–8.

- 41. Van Campen LE, Dennis JM, Hanlin RC, King SB, Velderman AM: One-year audiologic monitoring of individuals exposed to the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. J Am Acad Audiol1999; 10(5): 231–47.

- 42. Nageris BI, Attias J, Shemesh R: Otologic and audiologic lesions due to blast injury. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol2008; 19(3–4): 185–91.

- 43. Joseph AR, Shaw JL, Clouser MC, MacGregor AJ, Galarneau MR: Impact of blast injury on hearing in a screened male military population. Am J Epidemiol2018; 187(1): 7–15.

- 44. Tsao JW, Stentz LA, Rouhanian M, et al: Effect of concussion and blast exposure on symptoms after military deployment. Neurology2017; 89(19): 2010–6.

- 45. Remenschneider AK, Lookabaugh S, Aliphas A, et al: Otologic outcomes after blast injury: the Boston Marathon experience. Otol Neurotol2014; 35(10): 1825–34.

- 46. Van Haesendonck G, Van Rompaey V, Gilles A, Topsakal V, Van de Heyning P: Otologic outcomes after blast injury: the Brussels bombing experience. Otol Neurotol2018; 39(10): 1250–5.

- 47. Phillips JS, McFerran DJ, Hall DA, Hoare DJ: The natural history of subjective tinnitus in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of no-intervention periods in controlled trials. Laryngoscope2018; 128(1): 217–27.

- 48. Shargorodsky J, Curhan GC, Farwell WR: Prevalence and characteristics of tinnitus among US adults. Am J Med2010; 123(8): 711–8.

- 49. Sharkey JM, Rennix CP: Assessment of changes in mental health conditions among sailors and marines during postdeployment phase. Mil Med2011; 176(8): 915–21.

- 50. Wallhäusser-Franke E, Schredl M, Delb W: Tinnitus and insomnia: is hyperarousal the common denominator?Sleep Med Rev2013; 17(1): 65–74.

- 51. Miura M, Goto F, Inagaki Y, Nomura Y, Oshima T, Sugaya N: The effect of comorbidity between tinnitus and dizziness on perceived handicap, psychological distress, and quality of life. Front Neurol2017; 8: 722.

- 52. Bhatt JM, Bhattacharyya N, Lin HW: Relationships between tinnitus and the prevalence of anxiety and depression. Laryngoscope2017; 127(2): 466–9.

- 53. Weidt S, Delsignore A, Meyer M, et al: Which tinnitus-related characteristics affect current health-related quality of life and depression? A cross-sectional cohort study. Psychiatry Res2016; 237: 114–21.

- 54. Henry JA, Griest S, Thielman E, McMillan G, Kaelin C, Carlson KF: Tinnitus functional index: development, validation, outcomes research, and clinical application. Hear Res2016; 334: 58–64.

- 55. Jalilvand H, Pourbakht A, Haghani H: Hearing aid or tinnitus masker: which one is the best treatment for blast-induced tinnitus? The results of a long-term study on 974 patients. Audiol Neurootol2015; 20(3): 195–201.

- 56. Clifford RE, Baker D, Risbrough VB, Huang M, Yurgil KA: Impact of TBI, PTSD, and hearing loss on tinnitus progression in a US marine cohort. Mil Med2019; 184(11–12): 839–46.

- 57. Hinton DE, Chhean D, Pich V, Hofmann SG, Barlow DH: Tinnitus among Cambodian refugees: relationship to PTSD severity. J Trauma Stress2006; 19(4): 541–6.

- 58. Shi Y, Robb MJ, Michaelides EM: Medical management of tinnitus: role of the physician. J Am Acad Audiol2014; 25(1): 23–8.

- 59.

- 60. Cantley LF, Galusha D, Cullen MR, et al: Does tinnitus, hearing asymmetry, or hearing loss predispose to occupational injury risk?Int J Audiol2015; 54: S30–6.

- 61. Rubak T, Kock S, Koefoed-Nielsen B, Lund SP, Bonde JP, Kolstad HA: The risk of tinnitus following occupational noise exposure in workers with hearing loss or normal hearing. Int J Audiol2008; 47(3): 109–14.