Introduction

According to The Childhood Bereavement Estimation Model, over 4.8 million children in the U.S. will experience the death of a parent or sibling before they reach adulthood and this number more than doubles by age 25, to 12.7 million (). In addition, in Canada, over 203,000 of the 7.5 million children under the age of 18 are bereaved due to a close family member dying (). Until now, studies on parental death exclusively experienced by the adolescent population have been limited, as most studies mix data on both children and adolescents or on both adolescents and adults (; ). This combination of different populations may render the data analysis biased, since adolescence is a particular phase of life with a different neurodevelopment process compared to childhood and young adulthood (). Moreover, some studies included adolescents and adults who had experienced other types of grief, such as the death of a friend () or were also limited to Anglo-American and Mexican American participants only, excluding other ethnicities.

The adolescent period refers to individuals between the ages of 10 and 19 years () and is characterized as a time of intense change, in biological, psychological, and social development (, p. 41). Adolescence is also characterized by a particular brain neurodevelopment, the final growth of the frontal lobe; in particular, the brain stem, cerebellum, occipital lobe, parietal lobe, frontal lobe, and temporal lobe actively mature during adolescence. The frontal lobes which are involved in problem solving, spontaneity, memory, language, initiation, judgment, impulse control, and social and sexual behavior complete their groth at the end of adolescence, beginning of young adulthood (, p. 451).

Therefore, it is logical to think that a perturbation or a psychological trauma during this neurodevelopmental period can generate consequences in terms of both mental health and psychological suffering. This period is significantly different from both childhood and adulthood. While the parent/child attachment is characterized by a necessary and dependent bond, early adolescence is characterized by ambivalent expressions of dependence and independence (, p. 1271), accompanied by a need to detach from one’s parents and family. According to the WHO Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health Report, younger adolescents may be particularly vulnerable when their capacities are still developing but are beginning to move beyond the confines of their families. Furthermore, the life changes that occur during the adolescent years may incur health repercussions throughout adulthood as well ().

For these reasons, mourning the death of a parent in adolescence may be especially complicated. More specifically, as stated by : “The tasks of adolescence, such as separation from parental objects () and establishing oneself in the adolescent group () are being negotiated alongside the demanding work of mourning” (p. 26). Although therapy can guide and help the bereaved adolescent, “mourning is a lifelong process” whereby feelings of grief can re-emerge as life events unravel. Within this context of understanding adolescence as a unique period of time, unlike most studies that co-mingle adolescents and children, this review focuses specifically on isolating adolescent research from children and adult studies.

Unfortunately, while the literature clearly documents the potential negative impacts of parental loss during adolescence, there is no shared understanding of how adolescents experience this grieving process. Some psychoanalytic theories from the eighties hypothesize that the death of a parent in earlier adolescence causes a regression to a less mature state since the process of separation is interrupted by the death; while in older stages of adolescence, it can cause a “parentification”, transforming the individual into a surrogate parent, threating the independence and the complete separation from the surviving parent (). More recent studies have pointed out the complexity of responses in adolecents to the parent’sdeath, spanning from an “accelerated maturity” to the change of the vision of the world, perceiving events as random, unpredicatable and forcing the adolescent to attribute meaning to the loss during a period of personal growth (Tyson-Rawson, 1996).

Given the increasing importance of adapting counseling to adolescent needs and experiences, understanding how young people experience, process and cope with loss is critical in order to better guide this vulnerable population (; ; ; ; ). Within this context, this article reviews recent literature on grieving adolescents who have experienced parental loss in order to identify important themes about the grieving process and specific areas of future research needed.

Aim of the Review

The aim of this work is to review previous research on adolescents who have lost a parent (or both) during their adolescent years only, in order to aggregate what is known about the specific grief experiences of adolescents. Additionally, this review aims to identify and target specific areas where additional research could be particularly beneficial.

Methods

The methodology used to complete this review included identifying articles, reviewing them to identify relevant excerpts, aggregating those excerpts into themes, and writing a discussion that details each theme. The wide range of scales used to measure grief in the adolescent population, as well as the heterogeneity of the results of the present review, allowed for a coding system which resulted in a range of reactions to parental death, impacts of parental loss and responses to grief.

Literature Identification

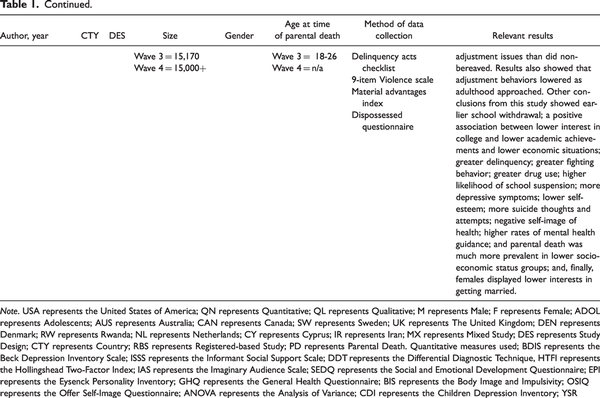

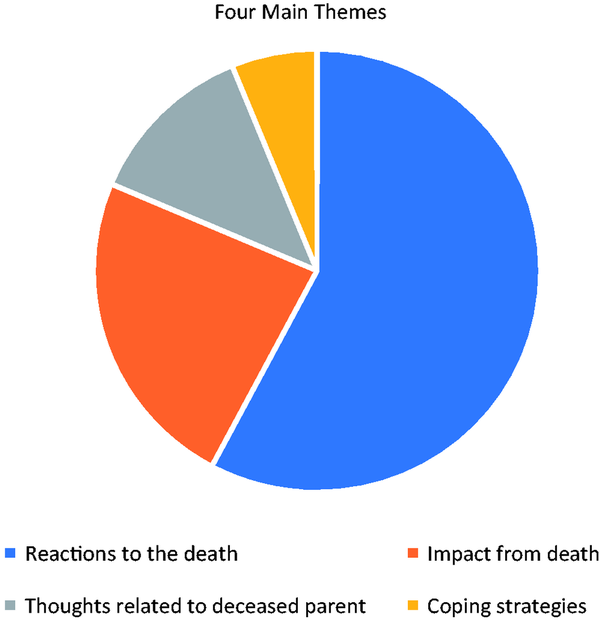

A review of the literature was conducted, ranging from 1987 to September 2020, using the databases PsychMed, Scopus CINHAL and Google Scholar. This review was carried out using the following keywords: adolescent OR teen OR teenager AND grieving OR grief OR bereavement AND parental death. Retrieved articles were included if their participant populations included adolescents who had experienced parental loss during their adolescent years only. The selection of articles examined and retained was done by reading the titles and abstracts. The potentially relevant articles were then retrieved in full text, and further assessed for inclusion. References of included studies were then also reviewed to identify additional studies. After removing duplicates and excluding articles not pertaining to adolescents bereaved due to parental death, the search resulted in a final count of 36 articles that met criteria for inclusion applicable this topic (see Figure1). Details about each article are summarized in Table 1.

Sources enlisted in Table 1 describes the final selected articles pertaining only to adolescent bereavement. Since this current review includes studies on parental death during adolescence only, all studies of adolescent bereavement that included other types of death, other than parental death, were excluded from this review. Mixed studies with adult/adolescent participants were also excluded.

Theme Identification

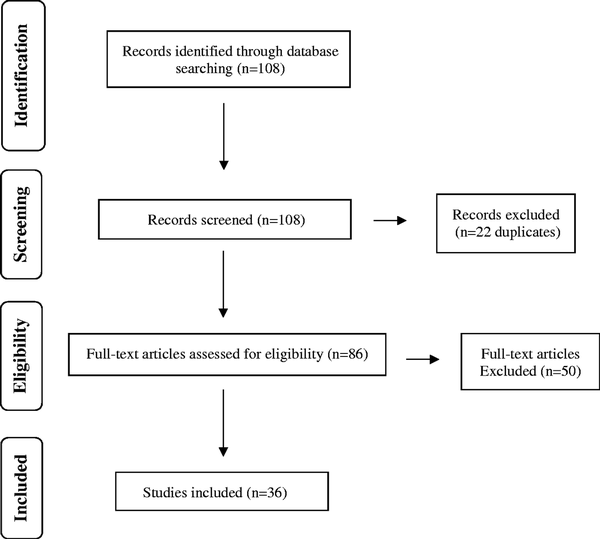

Having established the article set, the authors sought to identify quotes pertaining to adolescent grief as well as identifying impacts that grief had on their mental and physical health, their school life and their family unit. In total, 83 quotes were retained for analysis (which included a total of 135 codes). These quotes were then coded. The individual codes were then categorized into four main themes as depicted in Figure 2: (i) reactions to the death (n = 93, 57.8%), (ii) impact of death (n = 38, 23.6%), (iii) thoughts related to deceased parent (n = 20, 12.4%), and (iv) coping behaviors (n = 10, 6.2%).

Figure 1

Flowchart of Studies Selected.

Sources enlisted in Table 1 below describes the final selected articles pertaining only to adolescent bereavement. Since this current review includes studies on parental death during adolescence only, all studies of adolescent bereavement that included other types of death, other than parental death, were excluded from this review. Mixed studies with adult/adolescent participants were also excluded.

Figure 2

Distribution of Main Themes.

Note. Percentages: blue=56.1%, orange=24.3%, grey=13.3% and yellow=6.3%

Specifically, reactions to death was divided into physical (28), psychological (40), and behavioral (25). Psychological reactions were then further split into anxiety or depression (14) and everything else (26). Impact of death was also divided into impact on school (22) and impact on family (16). In the third category, thoughts related to the deceased, bond continuation (10) was separated as a distinct theme from thoughts related to the deceased (10). Finally, the most commonly cited needs category has a total of 10 codes. The details of this coding distribution are summarized in Figure 2.

Results

Literature Synthesis

The phenomenon we described in the current literature review is based on the feedback documented by bereaved adolescents to parental death. They are in order of frequency: (1) reactions to the death; (2) social impact caused by death; (3) thoughts related to deceased parent; and (4) coping behaviors.

Reactions to the Death

Behavioral

Excerpts about behavioral reactions from bereaving adolescents were predominantly negative. As per a study by , due to parental loss, adolescents experienced sleep disturbance, more irritability, anger and difficulties being with people. Moreover, a seminal study,one of the very first conducted in 1991 on this area of research, reported that in the second half of the year following the death, a few subjects experienced the onset of significant and new problems which included depression, alcohol abuse, delinquency, and threatened school failure (, p. 272). More specifically regarding behavioral reactions in the youth population dealing with grief, besides feeling sad, fearful and guilty, and crying over the deceased parent, some adolescents may go as far as experiencing suicide ideation after the death of a parent (). Similarly, stated that bereaved adults who experienced death of a parent in their youth reported significantly higher substance use, behavioural disengagement, and emotional eating than non-bereaved adults). In a study conducted by , of the 2,390 adult participants, 574 had lost a parent between the ages of 13 and 18. The authors reported no significant difference between ages and gender for those who had experienced parental loss regarding long-term negative effects. Moreover, youth obesity was also shown to be linked to early parental death, wherein the youth is now faced with a new family structure and subjected to a new way of parenting that may potentially affect eating habits. This study showed how, for adolescents, the experience of losing a parent may negatively affect coping behaviors later on in their adult years. Furthermore, adolescent problem behaviors, crying, anger, shock, psychiatric hospitalization and more sexual risk behaviors have been described as behavioral reactions to grief in this specific target population (; ; ).

Psychological: Other Than Anxiety and Depression

Excerpts from psychological reactions (other than anxiety and depression) were all negative, and detailed an increase of various psychological problems. For example, identified increased neuroticism; found increased levels of guilt and extreme fear; mention a prevalence of dysthymia and bipolar episodes as well as incidences of phobia and panic; identifies reported higher levels of suicide ideation; and extreme cases found the need for psychiatric hospitalization ().

Psychological: Anxiety and Depression

Anxiety and depression were the most commonly found reactions amongst bereaving adolescents. A study conducted by R. E. Gray (1987) suggests that depression was significantly found as a reaction to the loss of a parent and that “individuals categorized as having a passive/dependant personality were particularly prone to depression if they received low support” (p. 517). In addition, R. E. Gray (1987) also reported higher levels of depression in adolescents who described having poor past relationships with the deceased parent, most probably due to unstable family structures at the time of the death. Identically, reported that major depressive disorder as well as anxiety disorder were amongst the most prevalent mental disorders following parental loss. In addition, suggested that depression and anxiety were prevalent due to parental death.

Physical

Excerpts related to physical reactions due to parental loss range from sexual activity, severe problems such as sleep disturbance, and irritability (; ; ). Interestingly, sexual activities ranged from not being sexually active to being more sexually active than usual (). Insomnia was also detected as a physical reaction but more so in women than in men (). This disturbance in sleep was also found in a study conducted by , where the first six months after the death of a parent were greatly affected by disturbances in sleep.

Social Impact Caused by Death

School

Excerpts about impacts on school were predominantly (all but one) negative. The negative issues included decreased perception of performance, decreased performance, delinquency, failure to be promoted, decreased ability to focus, adjustment issues at school and when moving on to university. The positive excerpt was about increased energy and focus as a coping strategy that lead to increased performance. Specific coding for this section includes a range of behaviors. Codes included both general behaviors as problematic as well as specific behavior issues. An example of the decreased performance code that also includes decreased ability to focus is , reporting severe concentration problems and decline in school performance. Other researchers reported similar effects on school environment, including subjects who were threatened with failure to be promoted (, p. 272), and college adjustment (, p. 18). The only positive remark was from , where they report one of the main coping strategies as “the participants were working hard in school” as opposed to a study conducted by R. E. Gray (1987), in which school grades were negatively affected by parental death in those aged 15 years or younger, and were also lower when compared to older adolescents aged 15 and older.

Family

Excerpts about impacts on the family unit have shown the presence of both alcohol-related and psychological problems in their families (). Surviving parents or guardians were shown to play powerful roles in their child’s life, as stated by , although the relationship the participants had with their dead parents appeared to be just as important and was discussed by them in great depth. Similarly, a study by demonstrated that adolescents who had lost a parent ended up replacing the dead parent with household responsibility to help the surviving parent, a reaction known in pedo-psychiatry and psychology as child parentification (; ; ; F. B. ).The parentification is a relational process internal to family life, which leads the adolescent to take on greater responsibilities than his/her age and maturity typically does, and in a specific socio-cultural context leading them to assume the role of the parent for the widow parent. This coping strategy can have serious consequences for the adolescent’s development and their future relationships. In general, adolescents felt that a stronger support system was necessary for them to deal with this experience, such as feeling that the “surviving parent was not a supportive resource to help them cope with the death” (, p. 90). Furthermore, reported that adolescents spent less time at home and more time with peers, frequently relying on a best or special friend.

Thoughts Related to the Deceased Parent

Bond Continuation

Excerpts about bond continuation in multiple studies describe how the deceased parent, although physically gone, still remains in the minds and hearts of the adolescent. For example, report how inner guides, encounters, or mementos were reported as continued bonds by the grieving adolescents . For example, “Adolescents described encounters as unexpected experiences with a deceased parent and perceived them as positive or negative” (p. 361). Furthermore, in the same study, “keeping special items (mementos) as a way to connect with a deceased parent” (p. 361) was mentioned. Similarly, described how this continued bond with the deceased was due to the magnitude of loss that was experienced by the adolescent,who had felt a “strong presence of the deceased in dreams and in other people” (p.287).

These results confirm a previous study by Silverman and Silverman () reporting that children who were able to develop a way of keeping a relationship with their lost parent in their life were also better able to accept the reality of death. Finally, certain teenagers continued their bond with their dead parents by displaying little desire to relinquish the lost parent ().

Thoughts Directly Related to the Deceased

Excerpts from various studies showed how bereaved adolescents continued to keep the deceased parent in their mind through certain specific thoughts, such as identifying with the deceased parent by, for example, “acquiring the habits and interests of the deceased as well as feeling that the deceased is still with them” (, p. 287). Additionally, a study conducted by reported other types of thoughts directly related to the deceased, such as the bereaved teenager wishing strongly for the parent to be brought back to life, knowing that this was not the reality. Similarly, in another study by , it was documented how one adolescent enjoyed speaking about their deceased parent while another adolescent reported feeling uneasy about not having had the proper closure with their parent before their passing.

Coping Strategies

Excerpts directly related to specific needs of the adolescent population following parental death reflected the importance of friends and peers for how this population desires to be supported during their grief. For example, found that social support and friendships were instrumental in cultivating happiness after the death of a parent. Other important resources included either immediate family members or extended relatives () as well as school-based professional support (). Advantages of social support for the bereaved adolescent were reported as coming from either family, such as the surviving parent or siblings, and friends (). It was declared by all subjects in this study that emotional support, working hard in school and socializing with friends was crucial in how they all dealt with parental death. In fact, one participant stated that she had a lot of friends at the time she experienced parental loss and it was “really helpful and continues to be helpful even as life has gone” (p. 91). Although these coping mechanisms included family and friends, some participants also felt the need to self-isolate as they chose to be alone to grieve, for example, as they listened to music.

Despite the negative impacts of parental loss on adolescents, the following declarations show how losing a parent can have positive effects for youth as well, as one participant stated that “If you’re alone for a couple of weeks and you’re feeling down, then it builds character in my opinion” (). For these participants, speaking as an adult about the loss of their parent was still difficult. However, they reported that, in general, the loss made them “stronger, helped them gain maturity, and fostered a different perspective on life” (p. 92). Adulthood arrived more quickly for most of the bereaved adolescents as they reported how losing a parent changed them in both maturity and personal growth. Suffering seemed to be taken in a positive light, as one adolescent mentions that, “suffering makes you learn a lot about life, about yourself, about others, about everything — it makes you grow” (p. 92).

Gender Differences

Research in this area of study has shown that females have a tendency to grieve more on an emotional basis than do males, as “women had a higher degree of mourning accompanied by crying and the feeling of needing to cry than men” (, p. 287). This study reported gender differences in the adolescent population in the way they grieved. Participants in this study showed that women (a) declared having grieved longer on the death than did men, and (2) reported higher levels of unresolved grief than men. Similarly, a study conducted by found that females reported more general health problems and had higher neuroticism and also had a more negative perception of their school performance. In research, female adolescents partook in a study to express their perspectives of grief and coping due to parental loss (). Although women tended to describe the death experience as an “evolving process”, grieving was nonetheless a process that “is not encapsulated [and] neatly packaged and contained in a person’s life” (p. 92). Changes in their life included both (a) having a different identity within the new household structure, with an increased responsibility level towards the remaining parent, and (b) developing a newly formed relationship with the remaining parent. This new relationship is labelled by the author as “situational matrimony” (p. 92), resulting from the magnification of the relationship with the remaining parent.

Similarly the young women expressed changes in the family dynamics, such as becoming caregivers and having to take care of the remaining parent in similar ways as would the deceased parent (). Perceptions of family cohesion were significantly different between males and females in a study specifically assessing gender conducted by . When compared to non-bereaved youth, only maternally bereaved female participants had poor family cohesion perceptions that lasted into adulthood, as opposed to males, who did not. This study also showed that female adolescents’ well-being appears to be linked to the type of family relationship; thus female, compared to male bereaved adolescents, experience more emotional distress as a reaction to poor family cohesion. Finally, this study also reported more internalization by females as well as higher levels of vulnerability than their male counterparts. In the same study, females were also shown to have more responsibility within this new family structure than males had.

A study conducted by reported that coping styles differed between males and females, but (a) only in avoidant coping styles, (b) in females, and (c) due to depression. While this finding related to gender differences, the authors did report no significant differences between males and female across coping style. Similar findings were reported in a study conducted on various types loss and grief experienced by orphaned children in Kenya, with absence of gender difference on adjustment to loss and grief in orphan secondary school students (, p. 493). In general, boys kept more to themselves while girls spoke more about their grief than did boys, demonstrating gender differences when adjusting to grief and loss. To support this point, two other studies on gender differences have reported that females showed higher levels of emotional suffering than males but reported fewer behavior problems than did males (; ). suggest that these gender differences may be based on the different ways boys and girls are socialized. More research is needed in this area to support both male and female parentally bereaved adolescents. In a study conducted by , similar reactions to parental death were reported for both males and females. More specifically, results showed shared reactions for both males and females, such as greater substance use, greater delinquency, as well as fighting behavior and running away from home. In terms of depression, results showed that depression was seen more commonly in bereaved females than in males. Another interesting result showed that where bereaved males tended to delay marriage, females were less likely to even consider it.

Discussion and Conclusion

The death of a loved one can affect many aspects of one’s life, eliciting certain reactions defined as grief. The range includes negative impacts on physical, psychological, and behavioral states as well as negative impacts on family and school life. The main symptoms reported include the development of mood disorders and increased suicidal ideations, anxiety, insomnia, addiction, as well as an increased risk of mental disorders even after 19 years old (; ; ; ) or risk of cardiovascular diseases later in life (). In addition, adolescent grief may affect several aspects of their social life, more specifically in school performance and relationships with peers. In a study conducted by it was found that some of the participants saw a decrease in their success at school, got lower grades, participated in courses less and were less interested in social activities. Moreover, experiencing the death of a parent during adolescence can also include lower family cohesion, lower self-esteem, and higher hopelessness ().

Strikingly, there was one single instance of positive outcomes having been reported, that by in a study on increased academic focus and performance. This data showed an increase in resilience in a sub-group of adolescents, as the participants in this study described loss as acquiring personal growth as well as resilience. One teen stated that “suffering makes you learn a lot about life, about yourself, about others, about everything — it makes you grow” (p. 92). The increase in resilience after the loss of a parent was also reported by (Tyson-Rawson, 1996), pointing out an acceleration of the maturity process, independence, autonomy and a new direction of life choices. However, more research is needed to better understand the different responses in the adolescent populations regarding the impact of parental death during adolescence across a broad range of measures.

The risk of developing depression in adolescence after the parent’s death confirms previous studies carried out in children with regards to being at a higher risk for depression if parental loss is experienced in childhood, due to developmental immaturity and insufficiently developed coping capacities (). Similarly, in a study conducted by , in adolescents who experienced the loss of their father due to death or divorce, an increase in depression symptomatology was found 4–6 months after the separation. Similarly, the risk of depressive symptoms for bereaved adolescents from 12–15 yo was found to be twice as high as that of children from 8–11yo, with girls at twice the risk of boys (). Interestingly, a study in animals conducted by also confirmed the neurobiological consequences of parental loss during neurodevelopment, showing that the absence of the father, in monogamous biparental species, increases the risk for substance abuse and aggressive behavior, paralleled by a change in prefrontal cortex neurodevelopment ().

Furthermore, the large range of reactions and responses observed in adolescents who have experienced parental loss demonstrates the uniqueness of the human grief experience and how different these experiences may be. This provides stark evidence of the affirmation by Humphrey () for whom “the natural extension of appreciating the uniqueness of each person’s experience of loss and grief and her or his particular manner of adapting to loss is the importance of tailoring counseling strategies to client needs”. If the experience of loss and grief is unique, then counseling interventions that address those experiences must prioritize that uniqueness.

Given the heterogeneous responses of adolescents to grieving, it is not possible to apply general grieving processes to them. Indeed, the psychological complexity of adolescent responses, the different psychological elaboration of the loss, combined with the importance of peers and the intensity of emotions, make this age unique when faced with parental loss and mourning.

These conclusions create a clear mandate about the importance of developing deeper understanding of the adolescent bereavement process. Moreover, expresses the difficulties that arise when two important life adjustments (grief and adolescence) occur simultaneously , thus creating conflict with both tasks of grief and that of adolescence. It is therefore both imperative and crucial that clinicians and experts in this field find ways to support adolescents during such a delicate time (). Specifically, since recent research clearly documents the range of negative reactions and impacts, future research should shift focus to analyzing treatment strategies that can effectively intervene with a population that has specific neuropsychosocial features. Finally, because peers and school are known to play such an important role in adolescent lives (; ; ; ), particular attention should be paid to interventions that can happen within a school setting or one that involves peers. Even if at the beginning of the mourning process the adolescents may feel a distance and a rift from non-orphaned peers, and a separation from the life before and after the death, friendship can serve as an important part of the mourning process supporting the resolution of the bereavement (Tyson-Rawson, 1996).

The role played by peers and school seems indeed more important than family or other types of support groups for the adolescent, suggesting that the school environment could become the main support group for adolescents in bereavement. However, more studies are necessary to better understand the role played by the school and peers versus psychotherapy interventions in adolescent bereavement. Similarly, the studies here presented mainly describe the final mental outcome, but the individual trajectories of adolescents and the response from their environment to the loss of parents merit further research.

The current review omits discussing this psychotherapeutic approach with children as this subject goes beyond the scope of this review. However, it is important to note that, in the case of complicated grief, these therapies focus on loss processing and the restoration of a life without the deceased, using cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, and motivational interviewing ( Simon, 2013). Finally, complicated grief therapy with adolescents appears to be an effective method when the “treatment of complicated grief involves removing the impediments to successful resolution of the grieving process” (, p. 160). Data on bereaved adolescents, complicated grief and other therapeutic approaches merit further research as this area of research is limited ().

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the support of Dr. Andrew Churchill, affiliated with McGill University Writing Centre in Montreal (Canada) for his help in editing this paper. We would also like to thank Juliana Malka, affiliated with the department of educational psychology at McGill University in Montreal (Canada), who assisted in the literature review as well as in the editing process. Lastly, we would like to extend our gratitude to Mrs. Teodora Constantinescu, librarian at the Henry Kravitz Library at the Jewish General Hospital in Montreal (Canada).

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Québec Network on Suicide, Mood Disorders and Related Disorders.

ORCID iD Gabriella Gobbi https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4124-9825

References

- Andriessen K., Hadzi-Pavlovic D., Draper B., Dudley M., Mitchell P. B. (2018). The adolescent grief inventory: Development of a novel grief measurement. Journal of Affective Disorders, 240, 203–211.

- Apelian E., Nesteruk O. (2017). Reflections of young adults on the loss of a parent in adolescence. International Journal of Child, Youth Family Studies, 8(3/4), 79–100.

- Arain M., Haque M., Johal L., Mathur P., Nel W., Rais A., . . . Sharma S. (2013). Maturation of the adolescent brain. Neuropsychiatric Disease Treatment, 9, 449.

- Asgari, Z., & Naghavi, A. (2020). The experience of adolescents’ post-traumatic growth after sudden loss of father. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 25(2), 173–187.

- Bambico F. R., Lacoste B., Hattan P. R., Gobbi G. (2015). Father absence in the monogamous California mouse impairs social behavior and modifies dopamine and glutamate synapses in the medial prefrontal cortex. Cerebral Cortex, 25(5), 1163–1175.

- Bean C. G., Pingel R., Hallqvist J., Berg N., Hammarström A. (2019). Poor peer relations in adolescence, social support in early adulthood, and depressive symptoms in later adulthood—Evaluating mediation and interaction using four-way decomposition analysis. Annals of Epidemiology, 29, 52–59.

- Berg, L., Rostila, M., & Hjern, A. (2016). Parental death during childhood and depression in young adults-a national cohort study. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 57(9), 1092–1098.

- Birgisdóttir D., Bylund Grenklo T., Nyberg T., Kreicbergs U., Steineck G., Fürst C. J. (2019). Losing a parent to cancer as a teenager: Family cohesion in childhood, teenage, and young adulthood as perceived by bereaved and non‐bereaved youths. Psycho‐Oncology, 28(9), 1845–1853.

- Bonanno G. A., Wortman C. B., Nesse R. M. (2004). Prospective patterns of resilience and maladjustment during widowhood. Psychology and Aging, 19(2), 260–271.

- Boszormenyi-Nagy I. K. (2013). Between give and take: A clinical guide to contextual therapy. Brunner Routledge.

- Brent D. A., Melhem N. M., Masten A. S., Porta G., Payne M. W. (2012). Longitudinal effects of parental bereavement on adolescent developmental competence. Journal of Clinical Child Adolescent Psychology, 41(6), 778–791.

- Brewer J. D., Sparkes A. C. (2011). Young people living with parental bereavement: Insights from an ethnographic study of a UK childhood bereavement service. Social Science Medicine, 72(2), 283–290.

- Brown B. B., Larson J. (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. In Handbook of adolescent psychology: Contextual influences on adolescent development (Vol. 2). Steinberg, R. M. L. (Ed.), Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. 45(2), 402–[ZERO WIDTH SPACE]416

- Burns M., Griese B., King S., Talmi A. (2020). Childhood bereavement: Understanding prevalence and related adversity in the United States. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 90(4), 391–405.

- Cafferky J., Banbury S., Athanasiadou-Lewis C. J. (2018). Reflecting on parental terminal illness and death during adolescence: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Interpersona: An International Journal on Personal Relationships, 12(2), 180–196.

- Cait, C.-A. (2004). Spiritual and religious transformation in women who were parentally bereaved as adolescents. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying, 49(2), 163–181.

- Cait C. -A. (2005). Parental death, shifting family dynamics, and female identity development. OMEGA—Journal of Death and Dying, 51(2), 87–105.

- Cait C. -A. (2008). Identity development and grieving: The evolving processes for parentally bereaved women. British Journal of Social Work, 38(2), 322–339.

- Christ G. H., Siegel K., Christ A. E. (2002). Adolescent grief “it never really hit me . . . until it actually happened.” Journal of the American Medical Association, 288(10), 1269–1278. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.10.1269

- Cinzia P. A., Montagna L., Mastroianni C., Giuseppe C., Piredda M., de Marinis M. G. (2014). Losing a parent: Analysis of the literature on the experiences and needs of adolescents dealing with grief. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing, 16(6), 362–373.

- Corak M. (2001). Death and divorce: The long-term consequences of parental loss on adolescents. Journal of Labor Economics, 19(3), 682–715.

- Corr C. A., McNeil J.N. (1986). Adolescent and death. Springer Publishing Co.

- Dehlin L., Reg L. M. (2009). Adolescents’ experiences of a parent's serious illness and death. Palliative Supportive Care, 7(1), 13.

- Feigelman W., Rosen Z., Joiner T., Silva C., Mueller A. S. (2017). Examining longer-term effects of parental death in adolescents and young adults: Evidence from the national longitudinal survey of adolescent to adult health. Death Studies, 41(3), 133–143.

- Garber B. (1985). Mourning in adolescence: Normal and pathological. Adolescent Psychiatry, 12, 371–387.

- Gersten J. C., Beals J., Kallgren C. A. (1991). Epidemiology and preventive interventions: Parental death in childhood as a case example. American Journal of Community Psychology, 19(4), 481.

- Gobbi G., Low N. C., Dugas E., Sylvestre M.-P., Contreras G., O’Loughlin J. (2015). Short-term natural course of depressive symptoms and family-related stress in adolescents after separation from father. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 60(10), 417–426.

- Gray L. B., Weller R. A., Fristad M., Weller E. B. (2011). Depression in children and adolescents two months after the death of a parent. Journal of Affective Disorders, 135(1–3), 277–283.

- Gray R. E. (1987). Adolescent response to the death of a parent. Journal of Youth Adolescence, 16(6), 511–525.

- Gross R. (2018). The psychology of grief. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Hamdan S., Melhem N. M., Porta G., Song M. S., Brent D. A. (2013). Alcohol and substance abuse in parentally bereaved youth. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(8), 828–833.

- Hansen D. M., Sheehan D. K., Stephenson P. S., Mayo M. M. (2016). Parental relationships beyond the grave: Adolescents’ descriptions of continued bonds. Palliative Supportive Care, 14(4), 358.

- Hardman R. J. (2019). The death of a mother in adolescence. A qualitative study of the perceived impact on a woman’s adult life and the parent she becomes (Masters of arts in clinical counseling). University of Chester.

- Harris E. S. (1991). Adolescent bereavement following the death of a parent: An exploratory study. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 21(4), 267–281.

- Haxhe S. (2013). L'enfant parentifié et sa famille (The parentified child and his/her family). Érès.

- Hill R. M., Kaplow J. B., Oosterhoff B., Layne C. M. (2019). Understanding grief reactions, thwarted belongingness, and suicide ideation in bereaved adolescents: Toward a unifying theory. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 75(4), 780–793.

- Høeg B. L., Appel C. W., von Heymann-Horan A. B., Frederiksen K., Johansen C., Bøge P., . . . Bidstrup P. E. (2017). Maladaptive coping in adults who have experienced early parental loss and grief counseling. Journal of Health Psychology, 22(14), 1851–1861.

- Hollingshaus M. S., Smith K. R. (2015). Life and death in the family: Early parental death, parental remarriage, and offspring suicide risk in adulthood. Social Science & Medicine, 131, 181–189.

- Humphrey K. M. (2009). Counseling strategies for loss and grief. American Counseling Association.

- Karakartal D. (2012). Investigation of bereavement period effects after loss of parents on children and adolescents losing their parents. International Online Journal of Primary Education, 1(1), 37–57.

- Keenan A. (2014). Parental loss in early adolescence and its subsequent impact on adolescent development. Journal of Child Psychotherapy, 40(1), 20–35.

- Kiesner J., Kerr M., Stattin H. (2004). “Very important persons” in adolescence: Going beyond in-school, single friendships in the study of peer homophily. Journal of Adolescence, 27(5), 545–560.

- Kuntz B. (1991). Exploring the grief of adolescents after the death of a parent. Journal of Child Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 4(3), 105–109.

- Laufer M. (1966). Object loss and mourning during adolescence. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 21(1), 269–293.

- Lawrence E., Jeglic E. L., Matthews L. T., Pepper C. M. (2006). Gender differences in grief reactions following the death of a parent. OMEGA—Journal of Death Dying, 52(4), 323–337.

- Martin T. L., Doka K. J., Martin T. R. (2000). Men don't cry—Women do: Transcending gender stereotypes of grief. Taylor & Francis.

- Meshot C. M., Leitner L. M. (1993). Adolescent mourning and parental death. OMEGA—Journal of Death Dying, 26(4), 287–299.

- Munholland K. A. (2001). Experiencing and working with incongruence: Adaptation after parent death in adolescence [PhD thesis]. University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Oltjenbruns K. A. (1991). Positive outcomes of adolescents' experience with grief. Journal of Adolescent Research, 6(1), 43–53.

- Osterweis M., Solomon F., Green M. (1984). Bereavement: Reactions, consequences, and care. National Academy Press.

- Owaa J. A., Aloka P. J., Raburu P. (2015). The influence of emotional progression factors on adjustment to loss and grief on Kenyan orphaned secondary school students. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6(4), 489–498.

- Patterson P., Rangganaddhan A. (2010). Losing a parent to cancer: A preliminary investigation into the needs of adolescents and young adults. Palliative and Supportive Care, 8, 255–265.

- Raphael B., Cubis J., Dunne M., Lewin T., Kelly B. (1990). The impact of parental loss on adolescents' psychosocial characteristics. Adolescence, 25(99), 689–701.

- Ratnamohan L., Mares S., Silove D. (2018). Ghosts, tigers and landmines in the nursery: Attachment narratives of loss in Tamil refugee children with dead or missing fathers. Clinical Child Psychology Psychiatry, 23(2), 294–310.

- Raza S., Adil A., Ghayas S. (2008). Impact of parental death on adolescents’ psychosocial functioning. Journal of Psychosocial Research, 3(1), 1–11.

- Rotheram-Borus M. J., Stein J. A., Lin Y.-Y. (2001). Impact of parent death and an intervention on the adjustment of adolescents whose parents have HIV/AIDS. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology, 69(5), 763.

- Ryan A. M. (2000). Peer groups as a context for the socialization of adolescents’ motivation, engagement, and achievement in school. Educational Psychologist, 35(2), 101–111.

- Salloum A., Bjoerke A., Johnco C. (2019). The associations of complicated grief, depression, posttraumatic growth, and hope among bereaved youth. OMEGA—Journal of Death Dying, 79(2), 157–173.

- Servaty H. L., Hayslip B. Jr. (2001). Adjustment to loss among adolescents. OMEGA—Journal of Death and Dying, 43(4), 311–330.

- Silverman S. M., Silverman P. R. (1979). Parent-child communication in widowed families. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 33(3), 428–441.

- Simon F. B., Stierlin H., Wynne L. C. (1985). The language of family therapy: A systemic vocabulary and sourcebook. Family Process Press.

- Simon N. M. (2013). Treating complicated grief. Journal of the American Medical Association, 310(4), 416–423.

- Stikkelbroek Y., Bodden D. H., Reitz E., Vollebergh W. A., van Baar A. L. (2016). Mental health of adolescents before and after the death of a parent or sibling. European Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(1), 49–59.

- Stikkelbroek Y., Prinzie P., de Graaf R., Ten Have M., Cuijpers P. (2012). Parental death during childhood and psychopathology in adulthood. Psychiatry Research, 198(3), 516–520.

- Tang A., Lahat A., Crowley M. J., Wu J., Schmidt L. A. (2019). Neurodevelopmental differences to social exclusion: An event-related neural oscillation study of children, adolescents, and adults. Emotion, 19(3), 520.

- Tyson-Rawson K. (1996). Adolescent response to a death of a parent. In Corr C. A., Balk D. E. (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent death and bereavement. Springer Publishing Company.(pp.155-172)

- Unterhitzenberger J., Rosner R. (2014). Lessons from writing sessions: A school-based randomized trial with adolescent orphans in Rwanda. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), 24917.

- Walsh K. (2011). Grief and loss: Theories and skills for the helping professions. Pearson Australia Limited.

- Wetherell J. L. (2012). Complicated grief therapy as a new treatment approach. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 14(2), 159.

- Worden J. W. (1982). Grief counseling and grief therapy: A handbook for the mental health practitioner. Springer Publishing Company.

- Worden J. W. (1996). Children and grief: When a parent dies. Guilford Press.

- World Health Organization. (2012). Maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health: Progress report 2010-2011: Highlights. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44873

- World Health Organization. (2021). Adolescent health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health/#tab = tab_1

- Wortman C. B., Silver R. C. (2001). The myths of coping with loss revisited. In Stroebe M. S., Hansson R. O., Stroebe W., Schut H. (Eds.), Handbook of bereavement research: Consequences, coping, and care (pp. 405–430). American Psychological Association.