Introduction

Whilst colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common tumours in adults, it is rarely seen in younger patients. According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database, the incidence of CRC is 2.7 per 100,000 persons in patients younger than 25 years of age in the United States [-]. However, 1–4% of all CRC cases are diagnosed in persons below 25–30 years of age [-]. Although the incidence of CRC in the overall population has decreased, the incidence of CRC amongst young adults has increased over the last 2–3 decades [, ]. Due to the rarity of the disease in young cases, limited information is available on the clinical features of CRC in younger ages. Clinical management of the disease in young age groups is generally performed according to the experience of centres treating adult CRC patients. The survival rates for young CRC patients are reportedly worse than those for adult patients, probably due to the advanced stage of the disease in younger patients upon diagnosis and the presence of a poorer histologic subtype and grade (high-grade, mucinous type). In the literature, only a few studies have compared the age groups of CRC [, -]. These studies, for example, compared CRC patients in the age groups 0–19 versus 20–25 years [], ≤20 versus >20 years [], and ≤20 versus 21–30 years []. In the current study, we investigate the clinicopathologic and prognostic differences of three age groups of CRC patients [i.e., child/adolescent (0–19 years), young adults (20–25 years), and adults (>25 years)].

Materials and Methods

Young (≤25 years) CRC patients who had been treated at referral centres in Turkey between May 2003 and December 2015 were included in this study. Adult patients (>25 years) treated between October 2006 and November 2012 at the Dicle University were retrospectively determined from medical records and included as the control group. Patients with inadequate information of medical history and histopathologic features were excluded from the study. Patients were divided into three age groups: child/adolescents (10–19 years), young adults (20–25 years), and adults (>25 years). Age, sex, symptoms at the time of diagnosis, interval from presentation to diagnosis, presentation status (acute or not acute), family history, presence of polyposis coli, histopathologic features, tumour localisation, tumour stage at the time of diagnosis, treatment modalities, site of metastasis, survival time, and outcomes were detected from the patients’ records. Tumour stage was assessed according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging System 7th (AJCC 7th). Patients admitted to the emergency room with ileus and/or rigid abdomen were recorded as patients with acute presentation.

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the date of diagnosis to death. Event-free survival (EFS) was defined as the interval between diagnosis of CRC and recurrence or progression, second malignancy, death from any cause, or last contact. OS and EFS were calculated via the Kaplan-Meier method, and patient groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test, χ2 test, or Fisher’s exact test as necessary.

Results

Patient Characteristics

One hundred and seventy-three out of a total of 15,654 patients (1.1%; all age groups) from 20 referral centres in Turkey were included in this study. The median age of this group was 23 years (range, 10–25). Of the 173 patients enrolled, 32 (18.5%) were in the child/adolescent group, whilst 141 (81.5%) were in the young adult group. The control group included 612 CRC patients identified retrospectively from Dicle University medical records. After the exclusion of 275 patients due to inadequate medical information (mostly medical history), 237 patients were defined as control group. The median age of this group was 48 years (range, 26–94).

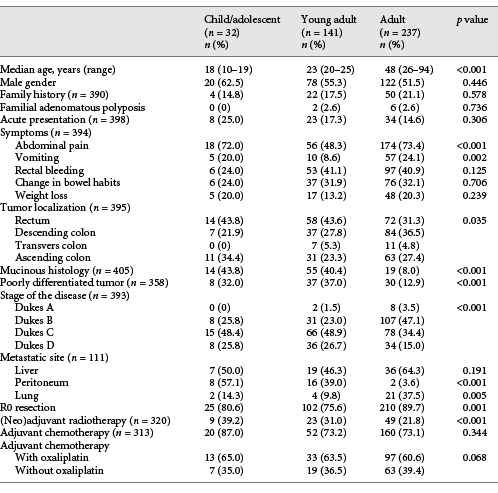

No statistical differences in gender were found between any two groups (males made up 62.5, 55.3, and 51.5% of the child/adolescent, young adult, and adult groups, respectively, p = 0.446). The percentage of patients with a family history of CRC and familial adenomatous polyposis history in the child/adolescent, young adult, and adult groups were 14.8% (n = 4) and 0%, 17.5% (n = 22) and 2.6% (n = 2), and 21.1% (n = 50) and 2.6% (n = 6), respectively (p = 0.578 and 0.736). The clinicopathologic characteristics of the patients are summarised in Table 1.

Symptoms and Presentation

The most common symptom in all age groups (n = 378, 65.6%) was abdominal pain. Abdominal pain (in adolescents 72.0% [n = 18], in young adults 48.3% [n = 56], in adults 73.4% [n = 174], p < 0.001) and vomiting (in adolescents 20.0% [n = 5], in young adults 8.6% [n = 10], in adults 24.1% [n = 57], p = 0.002) were significantly more common symptoms in the adolescent and adult groups than in the young adult group. Although statistically not significant, rectal bleeding (in adolescents 24.0% [n = 6], in young adults 41.1% [n = 53], in adults 40.9% [n = 97], p = 0.125) and changes in bowel habits (in adolescents 24.0% [n = 6], in young adults 31.9% [n = 37], in adults 32.1% [n = 76], p = 0.706) were less common in adolescents than in other groups. Frequency of weight loss (in adolescents 20.0% [n = 5], in young adults 13.2% [n = 17], in adults 20.3% [n = 48], p = 0.239] was similar amongst groups. The proportions of adolescent, young adult, and adult patients with acute presentation were 25.0% (n = 8), 17.3% (n = 23), and 14.6% (n = 34), respectively (p = 0.306). The median interval between initiation of symptoms and diagnosis was 3 months (range, 0–35) in the child/adolescent group, 3 months (range, 0–48) in the young-adult group, and 4 months (range, 0–48) in the adult group (p = 0.710).

Tumour Localisation

The primary site of the tumour was the rectum in 36.5% of the patients (n = 144), descending colon in 32.4% of the patients (n = 128), transverse colon in 4.6% of the patients (n = 18), and ascending colon in 26.6% of the patients (n = 105). A significant difference between groups was found in terms of tumour site (rectal localisation was 43.8% [n = 14], 42.6 [n = 58], and 30.4% [n = 72] in the child/adolescent, young adult, and adult groups, respectively, p = 0.035).

Pathology and Staging

Mucinous or signet ring-type adenocarcinoma was observed in 21.8% (n = 88) of all patients, and significant differences were found amongst the three groups (43.8% in the child/adolescent group, n = 14; 40.4% in the young adult group, n = 50; 8.0% in the adult group, n = 19; p < 0.001). A poorly differentiated histologic subtype was more commonly seen in child/adolescents (32.0%, n = 8) and young adults (37.0%, n = 37) than in adults (12.9%, n = 30) (p < 0.001).

Ten patients had Dukes stage A (2.5%), 146 had Dukes stage B (37.2%), 159 had Dukes stage C (40.5%), and 78 had Dukes stage D (19.8%) disease at the time of diagnosis. A statistical difference was observed amongst groups in terms of stage. The ratio of metastatic patients was 25.8% (n = 8) in the adolescent group, 26.7% (n = 36) in the young adult group, and 15.0% (n = 34) in the adult group (p < 0.001).

Although the liver was the most common metastasis site in the young adult (46.3%) and adult (64.3%) groups, the peritoneum was the most common metastasis site in the adolescent group (57.1%). The frequency of peritoneal (57.1% [n = 8] in the adolescent group, 39.0% [n = 16] in the young adult group, and 3.6% [n = 2] in the adult group, p < 0.001) and lung (14.3% [n = 2] in the adolescent group, 9.8% [n = 4] in the young adult group, and 37.5% [n = 21] in the adult group, p = 0.005) metastasis differed amongst groups. However, the frequency of liver (50.0% [n = 7] in the adolescent group, 46.3% [n = 19] in the young adult group, and 64.3% [n = 36] in the adult group, p = 0.191) and bone (21.4% [n = 3] in the adolescent group, 4.9% [n = 2] in the young adult group, and 10.7% [n = 6] in the adult group, p = 0.194) metastasis was statistically similar between groups.

Treatment and Outcomes

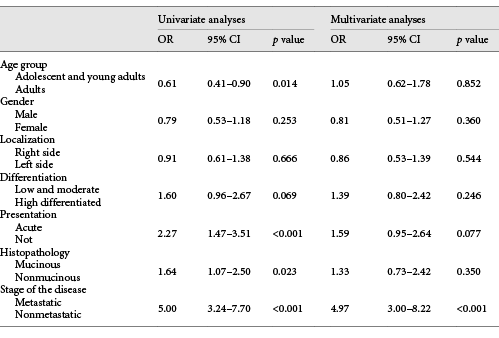

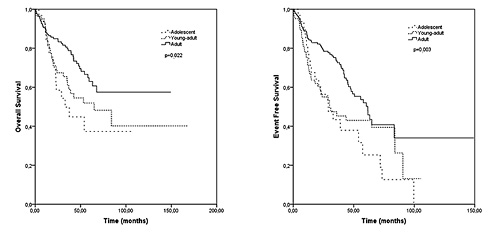

At the time of diagnosis, curative R0 resection had been performed in 25 (80.6%), 102 (75.6%), and 210 (89.7%) patients in the adolescent, young adult, and adult groups, respectively (p < 0.001). Radiotherapy was used as an adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatment in 81 (25.3%) patients (39.2% in adolescents, 31.0% in young adults, and 21.8% in adults, p < 0.001). Adjuvant chemotherapy usage (87.0, 73.2, and 73.1%, p = 0.344) and chemotherapy schedules (with oxaliplatin, 65.0, 63.5, and 60.6%, p = 0.068) were similar amongst the three groups. The median follow-up time was 33.6 months, and the median EFS in the adolescent, young adult, and adult groups was 29.0, 29.9, and 61.6 months, respectively (p = 0.003; Fig. 1). The median OS was 32.6 months in adolescents, 57.8 months in young adults, and not reached in adults (p = 0.022; Fig. 1). During univariate analyses, age group (adolescent and young adult vs. adult group, odds ratio [OR]: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.41–0.90; p = 0.014), histologic subtype (mucinous vs. nonmucinous, OR: 1.64, 95% CI: 1.07–2.50; p = 0.023), disease stage (metastatic vs. nonmetastatic, OR: 5.00, 95% CI: 3.24–7.70; p < 0.001), and type of presentation (acute vs. non, OR: 2.27, 95% CI: 1.47–3.51; p < 0.001) were significantly related to survival. However, gender (male vs. female, OR: 0.79, 95% CI: 0.53–1.18; p = 0.253), tumour differentiation (low, moderate, vs. high differentiation, OR: 1.60, 95% CI: 0.96–2.67; p = 0.069) and primary tumour location (right vs. left side, OR: 0.91, 95% CI: 0.61–1.38; p = 0.666) were not related to survival. During multivariate analyses, disease stage (metastatic vs. nonmetastatic, OR: 4.97, 95% CI: 3.00–8.22; p < 0.001) was the only factor affecting survival. Type of presentation (acute vs. not acute, OR: 1.59, 95% CI: 0.95–2.64; p = 0.077), age group (adolescent and young adult vs. adult group, OR: 1.05, 95% CI: 0.62–1.78; p = 0.852), histologic subtype (mucinous vs. nonmucinous, OR: 1.33, 95% CI: 0.73–2.42; p = 0.350), gender (male vs. female, OR: 0.81, 95% CI: 0.51–1.27; p = 0.360), tumour differentiation (low and moderate vs. highly differentiated, OR: 1.39, 95% CI: 0.80–2.42; p = 0.246) and primary tumour location (right vs. left side, OR: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.53–1.39; p = 0.544) were not related to survival, as determined by multivariate analyses (Table 2).

Fig. 1

Overall survival according to age group.

Discussion

CRC is a rare disease amongst young persons (≤25 years of age). Significant differences were identified between young and adult CRC patient groups in indirect comparative studies with a historical control group [, , -]. The present study is one of the largest series and the largest study thus far to evaluate differences in the clinicopathologic and prognostic features of the disease between three age groups (child/adolescent, young adult, and adult patients). Although our study has several limitations, such as a lack of adequate patient data due to its retrospective nature, its inclusion of a very large cohort of patients increases its importance.

In previous studies, the percentages of male patients in the adolescent, young adult, and adult patient groups were 57–75%, 45–48%, and 50–53%, respectively [, -]. In the present study, males respectively made up 62.5%, 55.3%, and 51.5% of the child/adolescent, young adult, and adult groups.

In their study, Ferrari et al. [] reported that 14, 55, and 13% of adolescent, young adult, and adult patients, respectively, have a family history of CRC; in the present study, however, the corresponding rates were 14.8%, 17.5%, and 21.1%. Whilst acute presentation was not reported in previous comparative studies, our study found that acute presentation is more common in child/adolescents than in other groups.

Only two previous studies revealed symptom comparisons between adolescent and young adult patients [, ]. Chantada et al. [] reported that weight loss, abdominal tumour, changes in bowel habits, and abdominal pain are more common in adolescents than in young adult patients. However, in our study, abdominal pain and nausea/vomiting were more common, whilst rectal bleeding was less common in adolescent patients than in young adult patients; and weight loss as well as changes in bowel habits were similar between groups []. In the current study, abdominal pain and vomiting were less common in young adults than in adolescent and adult patients, rectal bleeding and changes in bowel habits were less common in adolescents than in other groups, and weight loss rates were similar.

Ferrari et al. [] showed that mucinous histology and the high-grade tumour rate are similar between young adult and adult patients and less common than in adolescent patients. However, Kaplan et al. []reported no differences between adolescent and young-adult patients in terms of mucinous and poorly differentiated histology []. In the current study, a mucinous and poorly differentiated histology was observed more frequently in adolescent and young adult patients than in adult patients.

Disease stage was compared in these studies. Three previous studies reported a higher ratio of disease stage 3–4 patients in adolescents than in young adults [, , ]. Another study demonstrated that stage 4 disease is more common in child/adolescents than in adult patients []. In the current study, the ratio of patients with disease stages 3–4 was similar between the child/adolescent and young adult groups and higher in these two groups than that in the adult group. To the best of our knowledge, no study comparing metastasis sites in these age groups of patients with CRC has yet been published. We found that the peritoneum is a less common metastasis site whilst the lung and liver (numerically) are more common metastasis sites in the adult group than in other groups. Although younger patients had similar treatment options (e.g., surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy), the EFS and OS of these patients were poorer than those of adults. This information suggests that the available treatment options for young patients are not as effective as in adults.

Finally, in our study, survival outcomes were poorer in the child/adolescent and young adult groups than in the adult group. Several factors may be related to the poor survival outcome of child/adolescent patients. Adult CRC series suggest that the experience and specialisation of surgeons are prognostic variables influencing outcomes [-]. Indeed, the limited experience of paediatric surgeons may influence the survival of young CRC patients. Another possible factor affects EFS and OS is the tumour stage at the time of diagnosis. Young patients with CRC often present a more advanced disease stage at the time of diagnosis than adult patients. In our study, multivariate analyses revealed that tumour stage is an independent prognostic factor. Mucinous histology and poorly differentiated tumours were more frequent in the adolescent and young adult groups than in the adult group. Several studies indicating poor prognosis in patients with a mucinous histology are available in the literature [-]. Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma [] and peritoneal metastasis [, ], which occurs more often in adolescents and young adults than in adults, are also poor prognostic factors for CRC patients. Knowledge of these factors may help doctors explain poor outcomes to adolescent and young adult CRC patients.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that CRC presents different clinicopathologic and prognostic characteristics amongst different age groups. In particular, unlike previous studies, we revealed differences in survival rates and metastatic sites amongst three age groups. Due to the rarity of CRC in the childhood and adolescent age groups, clinical management and treatment approaches are generally designed according to experience obtained from the management of adult patients. Physicians should be aware of these differences and manage patients according to the differences observed to obtain better results. Surgical education for CRC amongst paediatric surgeons, which has emerged as a possible factor of poor outcomes, is important, especially in large centres. Genetic studies on adolescent and young adult age groups may help scientists to better understand the disease and find age-appropriate solutions. Tissue banking and tumoral mutational sequencing, for example, may refine therapies for these patient groups.

Statement of Ethics

This study was prepared according to the ethical guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Dicle University School of Medicine. Informed consent was not obtained because it was a retrospective study and most of the patients were dead at the time of study.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1. Pappo AS, Furman WL. Management of infrequent cancers in childhood. In: Pizzo PA, Poplack DC. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. 5th ed.Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. pp. 1172–201.

- 2. Ries LEM, Kosary C, Hankey B, et al SEER cancer statistic review. 2004;1975–2001.

- 3. Fairley TL, Cardinez CJ, Martin J, Alley L, Friedman C, Edwards B, et al Colorectal cancer in U.S. adults younger than 50 years of age, 1998-2001. Cancer. 2006;107(5Suppl):1153–61.

- 4. Kam MH, Eu KW, Barben CP, Seow-Choen F. Colorectal cancer in the young: a 12-year review of patients 30 years or less. Colorectal Dis. 2004;6(3):191–4.

- 5. Ferrari A, Rognone A, Casanova M, Zaffignani E, Piva L, Collini P, et al Colorectal carcinoma in children and adolescents: the experience of the Istituto Nazionale Tumori of Milan, Italy. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(3):588–93.

- 6. Van Langenberg A, Ong GB. Carcinoma of large bowel in the young. BMJ. 1972;3(5823):374–6.

- 7. Sessions RT, Riddell DH, Kaplan HJ, Foster JH. Carcinoma of the colon in the first two decades of life. Ann Surg. 1965;162(2):279–84.

- 8. Printz C. Colorectal cancer incidence increasing in young adults. Cancer. 2015;121(12):1912–3.

- 9. Connell LC, Mota JM, Braghiroli MI, Hoff PM. The rising incidence of younger patients with colorectal cancer: questions about screening, biology, and treatment. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2017;18(4):23.

- 10. Kaplan MA, Isikdogan A, Gumus M, Arslan UY, Geredeli C, Ozdemir N, et al Childhood, adolescents, and young adults (≤25 y) colorectal cancer: study of Anatolian Society of Medical Oncology. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013;35(2):83–9.

- 11. Sultan I, Rodriguez-Galindo C, El-Taani H, Pastore G, Casanova M, Gallino G, et al Distinct features of colorectal cancer in children and adolescents: a population-based study of 159 cases. Cancer. 2010;116(3):758–65.

- 12. Chantada GL, Perelli VB, Lombardi MG, Amaral D, Cascallar D, Scopinaro M, et al Colorectal carcinoma in children, adolescents, and young adults. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;27(1):39–41.

- 13. Libutti SK, Saltz LB, Willett CG. Cancer of the colon. In: DeVita VT Jr, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA. Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 9th ed.Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. pp. 1084–125.

- 14. Karnak I, Ciftci AO, Senocak ME, Büyükpamukçu N. Colorectal carcinoma in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34(10):1499–504.

- 15. Plunkett M, Murray M, Frizelle F, Teague L, Hinder V, Findlay M. Colorectal adenocarcinoma cancer in New Zealand in those under 25 years of age (1997-2007). ANZ J Surg. 2014;84(5):371–5.

- 16. Goligher J. Colorectal surgery as a specialty. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40(6):733–5.

- 17. Simons AJ, Ker R, Groshen S, Gee C, Anthone GJ, Ortega AE, et al Variations in treatment of rectal cancer: the influence of hospital type and caseload. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40(6):641–6.

- 18. Porter GA, Soskolne CL, Yakimets WW, Newman SC. Surgeon-related factors and outcome in rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 1998;227(2):157–67.

- 19. Maksimović S. [Survival rates of patients with mucinous adenocarcinoma of the colorectum]. Med Arh. 2007;61(1):26–9.

- 20. Verhulst J, Ferdinande L, Demetter P, Ceelen W. Mucinous subtype as prognostic factor in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65(5):381–8.

- 21. Compton CC, Fielding LP, Burgart LJ, Conley B, Cooper HS, Hamilton SR, et al Prognostic factors in colorectal cancer. College of American Pathologists Consensus Statement 1999. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124(7):979–94.

- 22. Lemmens VE, Klaver YL, Verwaal VJ, Rutten HJ, Coebergh JW, de Hingh IH. Predictors and survival of synchronous peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin: a population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(11):2717–25.

- 23. Jayne DG, Fook S, Loi C, Seow-Choen F. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2002;89(12):1545–50.