What is already known about the topic?

Advance care planning is seen as an important strategy to improve communication and the quality of life of patients and their relatives, particularly at the end of patients’ lives.

Despite an increasing interest in advance care planning, the uptake in clinical practice remains low.

Understanding of patients’ actual experiences with advance care planning is necessary in order to improve its implementation.

What this paper adds?

Although patients experience ambivalent feelings throughout the whole process of advance care planning, many of them report benefits, in particular, in hindsight.

‘Readiness’ is necessary to gain benefits from advance care planning, but the process of advance care planning itself could support the development of such readiness.

Patients need to feel comfortable in being open about their goals and preferences for future care with family, friends or their health care professional.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

In the context of patients with a life-threatening or life-limiting illness, personalised advance care planning, which takes into account patients’ needs and readiness, could be valuable in overcoming challenges to participating in it.

Further research is needed to determine the benefits of advance care planning interventions for the care of patients with a life-threatening or life-limiting illness.

Background

The growing interest in advance care planning (ACP) has resulted in a variety of ACP interventions and programmes. Most definitions of ACP incorporate sharing values and preferences for medical care between the patient and health care professionals (HCPs), often supplemented with input from and involvement of family or informal carers. Differences are seen in whether ACP focuses only on decision-making about future medical care or also incorporates decision-making for current medical care. Furthermore, there are different interpretations about for whom ACP is valuable, ranging from the general population towards a more narrow focus on patients at the end of their lives.– A well-established definition of ACP is presented in Box 1.

Box 1.

ACP refers to the whole process of discussion of end-of-life care, clarification of related values and goals, and embodiment of preferences through written documents and medical orders. This process can start at any time and be revisited periodically, but it becomes more focused as health status changes. Ideally, these conversations occur with a person’s health care agent and primary clinician, along with other members of the clinical team; are recorded and updated as needed; and allow for flexible decision making in the context of the patient’s current medical situation.

ACP is widely viewed as an important strategy to improve end-of-life communication between patients and their HCPs and to reach concordance between preferred and delivered care.– Moreover, there is a high expectation that ACP will improve the quality of life of patients as well as their relatives as it might decrease concerns about the future. Other potential benefits, which have been reported, are that ACP allows patients to maintain a sense of control, that patients experience peace of mind and that ACP enables patients to talk about end-of-life topics with family and friends.–

Despite evidence on the positive effects of ACP, the frequency of ACP conversations between patients and HCPs remains low in clinical practice.– This can partly be explained by patient-related barriers.,,,, Patients, for instance, indicate a reluctance to participate in ACP conversations because they fear being confronted with their approaching death; they worry about unnecessarily burdening their families and they feel unable to plan for the future.,,,, In addition, starting ACP too early may provoke fear and distress. However, current knowledge of barriers to ACP is initially derived from patients’ responses to hypothetical scenarios or from studies in which it remains unclear whether patients really had participated in such a conversation.,,,,, More recent research has shifted towards studies on the experiences of patients who actually took part in an ACP conversation. These studies can give a more realistic perspective and a better understanding of the patients’ position when having these conversations.

To our knowledge, there is only one review that summarises the perceptions of stakeholders involved in ACP and which includes some patients’ experiences. However, this review is limited to oncology. Given the fact that ACP may be of particular value for patients with a progressive disease due to the unpredictable but evident risk of deterioration and dying,,, this study focuses on the experiences of the broader population of patients with a life-threatening or life-limiting disease with ACP.

We aim to perform a systematic literature review to synthesise and describe the research findings concerning the experiences of patients with a life-threatening or life-limiting illness who participated in ACP. Our analysis provides an in-depth understanding of ACP from the patients’ perspective and might provide clues to optimise its value to patients.

Method

Design

A systematic literature search was conducted, the analysis relying on the method of thematic synthesis in a systematic review.

Search strategy

In collaboration with the Dutch Cochrane centre, we used a recently developed approach that is particularly suited to systematically review the literature in fields that are challenged by heterogeneity in daily practice and poorly defined concepts and keywords, such as the field of palliative care. The literature search strategy consisted of an iterative method. This method has, like all systematic reviews, three components: formulating the review question; performing the literature search and selecting eligible articles. The literature search, however, consists of combining different information retrieval techniques such as contacting experts, a focussed initial search, pearl growing, and citation tracking., These techniques are repeated throughout the process and are interconnected through a recurrent process of validation with the use of so-called ‘golden bullets’. ‘Golden bullets’ are articles that undoubtedly should be part of the review and are identified by the research team in the first phase of the search (phase question formulating). These ‘golden bullets’ are used to guide the development of the search string and to validate the search.

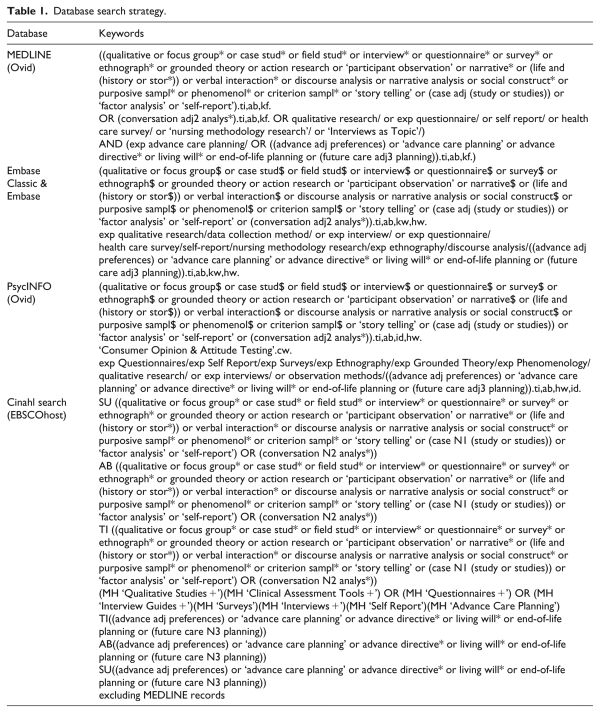

First, we undertook an initial search in PubMed and asked an internationally composed set of experts, who are actively involved in research and practice of ACP (n = 33) to provide articles that in their opinion, should be part of this review. These articles were used to refine the eligibility criteria. Based on these refined criteria, the ‘golden bullets’ (n = 7)– were selected from the articles identified from the initial search and by the experts. Second, the analysis of words used in the title, abstract and index terms of the ‘golden bullets’ were used to improve the search string. A new search was then conducted. The validation of this search was carried out by identifying whether all the ‘golden bullets’ were retrieved in this search. Not all ‘golden bullets’ could be identified in the retrieved citations after this first search. Therefore, the search string was adjusted several times and the process of searching and validation was repeated until the validation test was successful. Once the validation test was successful, the final search was carried out on 7 November 2016 using four databases namely MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase Classic & Embase, PsycINFO (Ovid) and CINAHL (EBSCOhost) (see Table 1 for search terms). Finally, the reference list of all included articles was cross referenced in order to identify additional relevant articles.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Papers were included based on the following inclusion criteria: the study must be an original empirical study; published in English; it must concern patients diagnosed with a life-threatening (illnesses for which curative treatment may be feasible but can fail) or a life-limiting illness (illnesses for which there is no reasonable hope of cure) and report experiences of patients who actually participated in ACP. We considered an activity to be ACP when it concerned a conversation which at least aimed at clarifying patients’ preferences, values and/or goals for future medical care and treatment. This conversation could have been conducted either by an HCP, irrespective of whether they were involved in the regular care for that particular patient or by persons who are not directly related to the patients’ care setting.

Studies reporting the experiences of multiple actors were excluded when the patients’ experiences could not be clearly distinguished. Studies in which only a part of the respondents had participated in ACP were also excluded when their experiences could not be distinguished from those patients who did not participate in ACP. Because of the difficulty of assessing the level of competence of the respondents, it was decided to exclude studies focussing on children aged under 18 and patients with dementia or a psychiatric illness.

Search outcomes

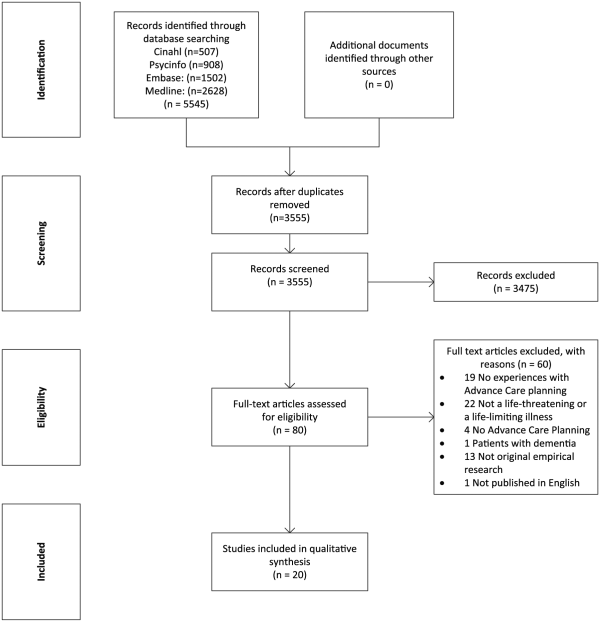

We identified 3555 unique papers. Two researchers (M.Z., L.J.J.) independently selected studies eligible for review based on the title and abstract using the inclusion criteria. Thereafter, the full text of the remaining studies (n = 80) was reviewed (M.Z., L.J.J.). The researchers discussed any disagreements until they achieved consensus. Remaining disagreements were resolved in consultation with a third researcher (M.C.K.). Finally, 20 articles were found to meet the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The web-based software platform Covidence supported the selection process.

Figure 1

Flow diagram illustrating the inclusion of articles for this review.

Quality assessment

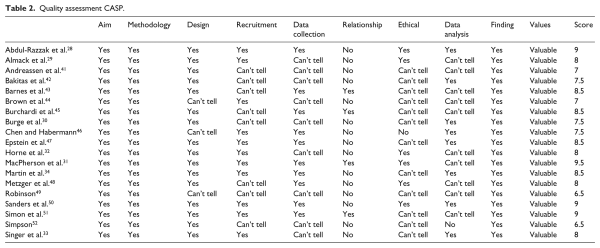

The methodological quality of the qualitative studies was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist, a commonly used tool in qualitative evidence syntheses. The CASP checklist consists of 10 questions covering the aim, methodology, design, recruitment strategy, data collection, relationship between researcher and participants, ethical issues, data analysis, findings and value of the study. A ‘yes’ was assigned when the criterion had been properly described (score 1), a ‘no’ when it was not described (score 0) and a ‘can’t tell’ when the report was unclear or incomplete (score 0.5). Total scores were counted ranging from 0 to 10. We considered a score of at least 7 as indicating satisfying quality.

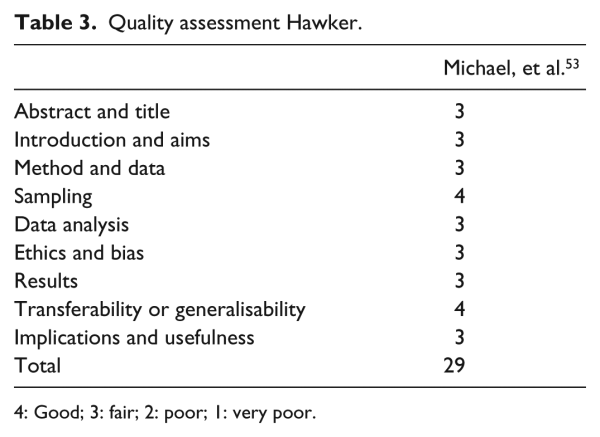

The methodological quality of mixed-method studies was assessed using the multi-method assessment tool developed by Hawker et al. This tool consists of nine categories: abstract and title; introduction and aims; method and data; sampling; data analysis; ethics and bias; results; transferability or generalisability; and implications. Each category was scored on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1–4, resulting in a total score from 9 (very poor) to 36 (good). We consider a score of at least 27 (=fair) as indicating satisfactory quality.

Two authors (M.Z., L.J.J.) independently assessed all included articles. Discrepancies were encountered in 33 of the 190 items assessed with the CASP and in 3 of the 9 items assessed with the Hawker scale. These were resolved by discussion.

The mean score of the methodological quality of the qualitative studies –,–, according to the CASP, was 8 out of 10 (range: 6.5–9.5). Main issues concerned limitations describing ethical issues ,,,–,,,, and the lack of information concerning the relationship between researchers and respondents –,–,,,,–, (Table 2). The quality of the mixed-method study was 29 (out of 36) according to the scale of Hawker (Table 3). Points were in particular lost in the categories ‘method and data’ and ‘data analysis’.

The appraisal scores are meant to provide insights into the methodological quality of the included studies. They were not used to exclude articles from the systematic review because a qualitative article with a low score could still provide valuable insights and thus be highly relevant to the study aim.,

Data extraction and analysis

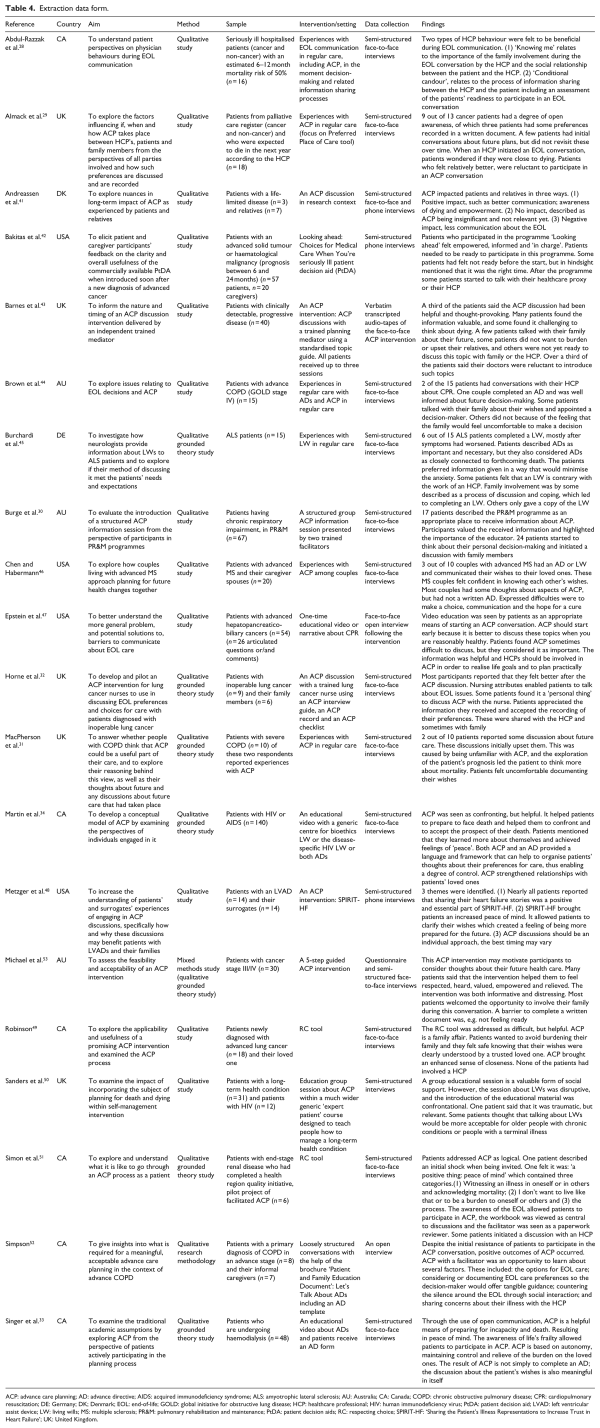

To achieve the aim of this systematic review, information was extracted on general study characteristics and the patients’ experiences and responses (Table 4). To provide context and to facilitate the interpretation of the results, the number of patients refusing participation in the study and the number of dropouts were identified, as well as the underlying reasons. This process was undertaken and discussed by two authors (M.Z., L.J.J.). Disagreements remained on three papers,, and were resolved in discussion with a third author (M.C.K.).

The thematic synthesis consisted of three stages. By using the software programme for qualitative analysis, NVivo 11, a transparent link between the text of the primary studies and the findings was created. First, the relevant fragments, with respect to the focus of this systematic review, were identified and coded. Second, the initial codes were clustered into categories and the content of these clusters was described. Finally, the analytical themes were generated. This analysis was performed by the first author (M.Z.) in collaboration with the last author (M.C.K.).

Results

Study characteristics

Of the 20 articles selected,–,– 19 had a qualitative study design –,– and one a mixed-methods design. All included studies were conducted in Western countries, mostly in Canada (n = 6) (Table 4).,,,,, The studies included patients with cancer ,,,,,,, as well as patients with other life-threatening or life-limiting illnesses (e.g. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),,, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV),, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)) (Table 4).–,,,,,,,– Most studies reported the experiences of patients in an advanced stage of their illness.,,,–,–,– A total of 14 studies reported patients’ experiences with an ACP intervention in a research context,,–,–,– the remaining six articles focussed on ACP experiences in daily practice (Table 4). ,,,–The studies labelled the conversations as ACP conversations–,–(n = 19) or as end-of-life conversations (n = 1).

Eight studies reported the number of refusals and/or the reasons why patients refused to participate in the study.,,,,,,, The total number of eligible patients in these eight studies was 579, of which 206 patients refused to participate. Patients refused for ‘practical’ reasons (n = 44), or felt too ill to participate (n = 42).,, Other reasons concerned logistics (e.g. could not be reached by phone; n = 42),,,, and some patients (n = 25) died during the period of recruitment.– Eleven patients (5%) were reported to have refused because they felt not ready to participate or were too upset by the word ‘palliative’., The number of dropouts remained unclear. Three studies reported reasons for drop out ,, showing that some patients were too disturbed by the topic to proceed with ACP. One patient reported feeling better and was, therefore, reluctant to follow-up the end-of-life conversation.

Synthesis of results

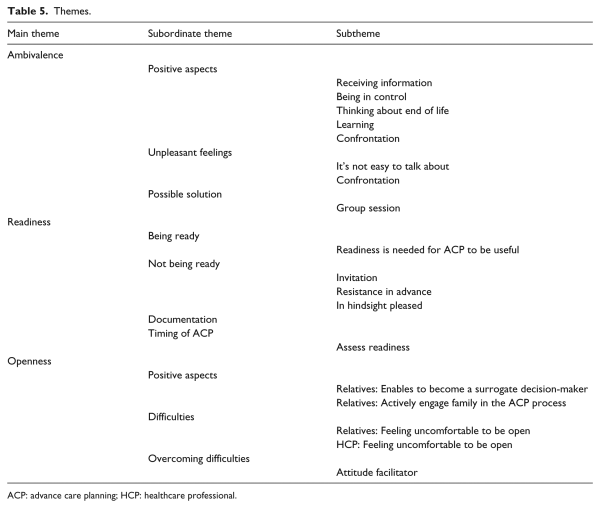

Three different, but closely related, main themes were identified which reflected the experiences of patients with ACP conversations namely: ‘ambivalence’, ‘readiness’ and ‘openness’. Themes, subordinated themes and subthemes, are presented in Table 5. ‘Ambivalence’ was identified in 18 studies –,–,,– and ‘readiness’ in 18 studies.–,–,– The theme ‘openness’ was found in all studies.

Ambivalence

Several studies reported the patients’ ambivalence when involved in ACP. From the invitation to participate in an ACP conversation to the completion of a written ACP document, patients simultaneously experienced positive as well as unpleasant feelings. Such ambivalence was identified as a key issue in five studies.,,,,Irrespective of whether the illness was in advanced stage, patients reported ACP to be informative and helpful in the trajectory of their illness, while participation in ACP was also felt to be distressing and difficult.,, ‘It’s not easy to talk about these things at all, but … information is power’. Thirteen studies showed that patients who participated in ACP were positive about participation or felt it was necessary for them to participate in ACP also described negative experiences. However, the nature of these was not specified further.–,,,,,–

Positive aspects

Looking at why patients experienced ACP as positive, studies mentioned the information patients received during the ACP conversation and the way it was provided.,,,,,,,Information that made patients feel empowered was clear, tailored towards the individual patient’s situation, and framed in such a way that patients felt it was delivered with compassion and with space for them to express accompanying feelings and emotions., Another positive aspect of ACP was that it provided patients a feeling of control. This was derived from their increased ability to make informed healthcare decisions,, and to undertake personal planning.,, Patients also mentioned that the ACP process offered them an opportunity to think about the end of their life. This helped them to learn more about themselves and their situation, such as what kind of care they would prefer in the future. In addition, participating in ACP made them feel respected and heard.–,–,,,– One patient summarised it by saying that ACP allowed him to feel that ‘everything was in place’.

Unpleasant feelings

Turning to the unpleasant feelings evoked during the process of ACP, these were often caused by the difficulty to talk about ACP, especially because of the confrontation with the end of life. Patients particularly experienced this confrontation at the moment of invitation and during the ACP conversation. Eleven studies,,,,,,,,–, of which eight concerned an ACP intervention in a research context,,,,,,,, reported that being invited and involved in ACP made patients realise that they were close to the end of their lives and this had forced them to face their imminent death.,,,,,,,,,, Four of these studies found that this resulted in patients feeling disrupted.,,, In particular, an increased awareness of the seriousness of their illness and that the end-of-life could really occur to them, was distressing.,,, A notable finding was that some patients in five studies,,,,, labelled the confrontation with their end-of-life as positive because it had helped them to cope with their progressive illness.

Possible solution

In order to overcome, or to soften, the confrontation with their approaching death, some patients offered the solution of a more general preparation. These patients had received general information on ACP through participation in a group ACP session with trained facilitators., They believed that the introduction of ACP in a more general group approach or by presenting it more as routine information was less directly linked with the message that they themselves had a life-threatening disease., In addition, patients who participated in a group setting mentioned that questions from other patients had been helpful to them. Particularly, those that they had not thought of themselves but of which the answers proved to be useful.

Readiness

During our analysis we noticed how influential the patients’ ability and willingness to face the life-threatening character of the disease and to think about future care was during this process. Patients, both in earlier and advanced stages of their disease, refer to this as their readiness to participate in an ACP conversation.,,,,,,,,

Being ready

One study involving seriously ill patients looked at their preferences regarding the behaviour of the physician during end-of-life communication. In response to their own ACP experience, several patients in this study suggested that an ACP conversation is only useful and beneficial when patients are ready for it.

Not being ready

Of the patients in the studies which addressed ‘readiness’, some had not yet felt ready to discuss end-of-life topics at the moment they were invited for an ACP conversation.,,,,,– This was true both for an ACP intervention in a research context or an ACP conversation in daily practice, irrespective of the stage of illness. These patients reported either an initial shock when first being invited ,, or their initial resistance to participate in an ACP conversation.,,,– This was particularly true because of them being confronted with the life-threatening nature of their disease.,,,,,– In addition, some patients were worried about the possible relationship between the process of ACP and their forthcoming death.,,,, The patients in one study reported that introducing ACP at the wrong moment could both harm the patient’s well-being and the relationship between the patient and the HCP.

In spite of the initial resistance of some patients to participate in an ACP conversation, most patients completed the conversation and in hindsight felt pleased about it.,,– In two studies, a few patients felt too distressed by the topic and, as a consequence, had not continued the ACP conversation.,

Documentation

In nine studies, patients’ experiences in writing down their values and choices for future medical care were reported.–,–,– Patients who participated in an ACP conversation and did not write a document about their wishes and preferences did not do so because they felt uncomfortable about completing such a document.,, This was particularly due to their sense of not feeling ready to do so.,, In addition, they mentioned their difficulty with planning their care ahead and their need for more information. Some patients felt reluctant to complete a document about their wishes and preferences due to their uncertainty about the stability of their end-of-life preferences in combination with their fear of no longer having an opportunity to change these.,,, However, the patients who completed a document indicated it as a helpful way to organise their thoughts and experienced it as a means of protecting their autonomy.–,–,, In a study about the experiences of ALS patients with a living will, a few said that they had waited until they felt ready to complete their living will. This occurred when they had accepted the hopelessness of the disease or when they experienced increasingly severe symptoms.

Timing of ACP

In addition, in three studies investigating patients’ experiences with an ACP intervention in a research context, patients emphasised that an ACP conversation should take place sooner rather than later.,, In a study among cancer patients about a video intervention as part of ACP, patients mentioned that ‘It is better to deal with these things when you are reasonably healthy’. In two studies, patients suggested that it would be desirable to assess the patient’s readiness for an ACP conversation by just asking patients how much information they would like to receive.,

Openness

In all included studies, it appeared that besides sharing information with their HCP or the facilitator who conducted the ACP conversation, patients were also stimulated to share personal information and thoughts with relatives, friends or informal carers. –,– ‘Openness’ in the context of ACP refers to the degree to which patients are willing to or feel comfortable about sharing their health status and personal information, including their values and preferences for future care, with relevant others.

Positive aspects

Some patients, including a number who were not yet in an advanced stage of the illness, positively valued being open towards the HCP about their options and wishes. An open dialogue enabled them to ask questions related to ACP and to plan for both current and future medical care.,,,,,, Openness towards relatives was also labelled as positive by many patients.,,,,–,,,,, Patients appreciated the relatives’ awareness of their wishes and preferences, which enabled them to adopt the role of surrogate decision-maker in future, should the patient become too ill to do so his or herself.,,,,–,,,,, Most patients thought their openness would reduce the burden on their loved ones.,,,,,,, In two studies, patients described a discussion with family members that led to the completion of the patients’ living wills., Because of these positive aspects of involving a relative in the ACP process, some patients emphasised that the facilitator should encourage patients to involve relatives in the ACP process and to discuss their preferences and wishes openly.,

Difficulties

On the other hand, openness did not always occur. Eight studies reported patients’ difficulties being open about their wishes and preferences towards others.,,,–,, Some patients had felt uncomfortable about discussing ACP with their HCP because they considered their wishes and preferences to be personal.,, Others felt that an ACP conversation concerned refusing treatment and, as such, was in conflict with the work of a doctor.,

The difficulties reported about involving relatives derived from patients’ discomfort in being open about their thoughts.,,, Some patients consciously decided not to share these. For instance, patients felt that the family would not listen or did not want to cause them upset.,,, The ACP conversation did occasionally expose family tensions such as feelings of being disrespected or about the conflicting views and wishes of those involved.,

Overcoming difficulties

According to the patients, the facilitator who conducted the ACP conversation had the opportunity to support patients to overcome some of these difficulties.,,,, Patients highlighted that when the facilitator showed a degree of informality towards the patient during the conversation, was supportive and sensitive – which in this context meant addressing difficult issues without ‘going too far’ – they felt comfortable and respected.,,, This enabled them to be open about their wishes and thoughts.,,,

Discussion

Main findings

This systematic review of research findings relating to the actual experiences with ACP of patients with a life-threatening or life-limiting illness shows that ‘ambivalence’, ‘readiness’ and ‘openness’ play an important role in the willingness and ability to participate in ACP. Previous studies involving hypothetical scenarios for ACP indicate that it can have both positive and negative aspects for patients.,,,, This systematic review now takes this further showing that individual patients can experience these positive and unpleasant feelings simultaneously throughout the whole ACP process. However, aspects of the ACP conversation that initially are felt to be unpleasant can later be evaluated as helpful. Albeit that patients need to feel some readiness to start with ACP, this systematic review shows that the ACP process itself can have a positive influence upon the patient’s readiness. Finally, consistent with the literature concerning perceptions of ACP,,,,, sharing thoughts with other people of significance to the patient was found to be helpful. However, this systematic review reveals that openness is also challenging and patients need to feel comfortable in order to be open when discussing their goals and plans for future care with those around them.

What this study adds

All three identified themes hold challenges for patients during the ACP process. Patients can appraise these challenges as unpleasant and this might evoke distress.– For example, the confrontation with being seriously ill and/or facing death, which comes along with the invitation and participation in an ACP conversation, can be a major source of stress. In addition, stress factors such as sharing personal information and wishes with significant others or, fearing the consequences of written documents which they feel they may not be able to change at a later date, may also occur later in the ACP process. All these stress factors pose challenges to coping throughout the ACP process.

The fact that the process of ACP in itself may help patients to discuss end-of-life issues more readily, might be related to aspects of the ACP process which patients experience as being meaningful to their specific situation. It is known from the literature on coping with stress that situational meaning influences appraisal, thereby diminishing the distress. Participation in the ACP process suggests that several perceived stress factors can be overcome by the patient. Although ACP probably does not take away the stress of death and dying, participation in ACP, as our results show, may bring patients new insights, a feeling of control, a comforting or trusting relationship with a relative or other experiences that are meaningful to them.

Patients use a variety of coping strategies to respond to their life-threatening or life-limiting illness and, since coping is a highly dynamic and individual process, the degree to which patients’ cope with stress can fluctuate during their illness.–

ACP takes place within this context. Whereas from the patients’ perspective ACP may be helpful, HCPs should take each individual patients’ barriers and coping styles into account to help them pass through the difficult aspects of ACP in order to experience ACP as meaningful and helpful to their individual situation.

The findings of this systematic review suggest that the uptake and experience of ACP may be improved through the adoption of a personalised approach, reflectively tailored to the individual patient’s needs, concerns and coping strategies.

While it is widely considered to be desirable that all patients approaching the end of life should be offered the opportunity to engage in the process of ACP, a strong theme of this systematic review is the need for ‘readiness’ and the variability both in personal responses to ACP and the point in each personal trajectory that patients may be receptive to such an offer. Judging patients’ readiness’, as a regular part of care, is clearly a key skill for HCPs to cultivate in successfully engaging patients in ACP. An aspect of judging patients’ ‘readiness’ is being sensitive to patients’ oscillation between being receptive to ACP and then wishing to block this out. Some patients may never wish to confront their imminent mortality. However, it is evident that ACP may be of great value, even for patients who were initially reluctant to engage, or who found the experience distressing. Therefore, HCPs could provide information about the value of participation in ACP, given the patient’s individual situation.

If patients remain unaware of ACP, they are denied the opportunity to benefit. Consequently, it is important that information about the various ACP options should be readily available in a variety of formats in each local setting. Given the challenges of ACP and the patient’s need to feel comfortable in sharing and discussing their preferences, HCPs should be sensitive and willing to openly discuss the difficulties involved.

Several additional strategies can be helpful. First, ACP interventions can include a variety of activities, for example, choosing a surrogate decision-maker, having the opportunity to reflect on goals, values and beliefs or to document one’s wishes. Separate aspects can be more or less relevant for patients at different times. Therefore, HCPs could monitor patients’ willingness to participate in ACP throughout their illness, before starting a conversation about ACP or discussing any aspect of it. Second, the option of participating in a group ACP intervention could be a helpful means of introducing the topic in a more ‘hypothetical’ and non-threatening way, especially for patients who are reluctant to participate in an individual ACP conversation. An initial group discussion could lower the barriers to subsequently introducing and discussing personal ACP with the HCP.,

The reality remains that discussing ACP with patients requires initiative and effort from HCPs. Even skilled staff in specialist palliative care roles experience reluctance to broach the topic and difficulty in judging how and when to do so.,, Therefore, it is important that HCPs are provided with adequate knowledge and training about all aspects of ACP (e.g. appointment of proxy decision-makers as well as techniques for sensitive discussion of difficult topics). It may be helpful for HCPs to have access to different practical tools or ACP interventions which they can use in the care of patients during their end-of-life trajectory. For example, an interview guide with questions that have been established to be helpful could offer guidance to HCPs when asking potentially difficult questions. For that reason, it is important for future research to study the benefits of (different aspects of) ACP interventions in order to improve the care and decision-making processes of patients with a life-threatening or life-limiting illness.

Limitations of the study

Some limitations of this systematic review should be taken into account. First, the articles included were research studies offering an ACP intervention in a research context or studies evaluating daily practice with ACP. It is likely that the patients included here were self-selected for participation in these studies because they felt ready to discuss ACP. This would represent a selection bias, influencing patients’ experiences with ACP positively. However, from the studies that reported patients’ refusals to participate, we learnt that part of the patients felt initial resistance to ACP and a small number of patients refused participation because they felt not ready. Second, our search was limited to articles published in English.

Conclusion

This systematic review of the evidence of patients’ experiences of ACP showed that patients’ ‘ambivalence’, ‘readiness’ and ‘openness’ play an important role in their willingness and ability of patients to participate in an ACP conversation. We recommend the development of a more personalised ACP, an approach which is reflectively tailored to the individual patient’s needs, concerns and coping strategies. Future research should provide insights into the potential for ACP interventions in order to benefit the patient’s experience of end-of-life care.

The authors thank Lotty Hooft and René Spijker for their insight and expertise in literature searches that greatly assisted this systematic review. They thank René Spijker also for performing the literature search. M.Z. has contributed to the design of the work, collected the data, analysed and interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. L.J.J. and M.C.K. have contributed to the design of the work, collected the data, analysed and interpreted the data, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. J.J.M.V.D., A.V.D.H., I.J.K., K.P., J.A.C.R. and J.S. have contributed to the design of the work, analysed and interpreted data, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Declaration of conflicting interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

M Zwakman

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2934-8740

JAC Rietjens

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0538-5603

References

- 1. Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JA, Van Der Heide A. The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2014; 28(8): 1000–1025.

- 2. Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017.

- 3. National Academy of Medicine (NAM). Dying in America: improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, DC: The National Academic Press, 2015.

- 4.

- 5. Teno JM, Nelson HL, Lynn J. Advance care planning. Priorities for ethical and empirical research. Hastings Cent Rep 1994; 24(6): S32–S36.

- 6. Kirchhoff KT, Hammes BJ, Kehl KA, et al. Effect of a disease-specific planning intervention on surrogate understanding of patient goals for future medical treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010; 58(7): 1233–1240.

- 7. Morrison RS, Chichin E, Carter J, et al. The effect of a social work intervention to enhance advance care planning documentation in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53(2): 290–294.

- 8. Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, et al. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010; 340: c1345.

- 9. Davison SN. Facilitating advance care planning for patients with end-stage renal disease: the patient perspective. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 1(5): 1023–1028.

- 10. Seymour J, Almack K, Kennedy S. Implementing advance care planning: a qualitative study of community nurses’ views and experiences. BMC Palliat Care 2010; 9: 4.

- 11. Fried TR, Bullock K, Iannone L, et al. Understanding advance care planning as a process of health behavior change. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009; 57(9): 1547–1555.

- 12. Musa I, Seymour J, Narayanasamy MJ, et al. A survey of older peoples’ attitudes towards advance care planning. Age Ageing 2015; 44(3): 371–376.

- 13. Mullick A, Martin J, Sallnow L. An introduction to advance care planning in practice. BMJ 2013; 347: f6064.

- 14. Janssen DJ, Spruit MA, Schols JM, et al. A call for high-quality advance care planning in outpatients with severe COPD or chronic heart failure. Chest 2011; 139(5): 1081–1088.

- 15. Horne G, Seymour J, Payne S. Maintaining integrity in the face of death: a grounded theory to explain the perspectives of people affected by lung cancer about the expression of wishes for end of life care. Int J Nurs Stud 2012; 49(6): 718–726.

- 16. Barakat A, Barnes SA, Casanova MA, et al. Advance care planning knowledge and documentation in a hospitalized cancer population. Proc 2013; 26(4): 368–372.

- 17. Schickedanz AD, Schillinger D, Landefeld CS, et al. A clinical framework for improving the advance care planning process: start with patients’ self-identified barriers. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009; 57(1): 31–39.

- 18. Jabbarian LJ, Zwakman M, van der Heide A, et al. Advance care planning for patients with chronic respiratory diseases: a systematic review of preferences and practices. Thorax 2018; 73(3): 222–230.

- 19. Scott IA, Mitchell GK, Reymond EJ, et al. Difficult but necessary conversations–the case for advance care planning. Med J Aust 2013; 199(10): 662–666.

- 20. Simon J, Porterfield P, Bouchal SR, et al. ‘Not yet’ and ‘Just ask’: barriers and facilitators to advance care planning – a qualitative descriptive study of the perspectives of seriously ill, older patients and their families. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015; 5(1): 54–62.

- 21. Johnson S, Butow P, Kerridge I, et al. Advance care planning for cancer patients: a systematic review of perceptions and experiences of patients, families, and healthcare providers. Psychooncology 2016; 25(4): 362–386.

- 22. Kimbell B, Murray SA, Macpherson S, et al. Embracing inherent uncertainty in advanced illness. BMJ 2016; 354: i3802.

- 23. Rietjens JAC, Sudore RL, Connolly M, et al. Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: an international consensus supported by the European association for palliative care. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18(9): e543–e551.

- 24. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008; 8: 22–88.

- 25. Papaioannou D, Sutton A, Carroll C, et al. Literature searching for social science systematic reviews: consideration of a range of search techniques. Health Info Libr J 2010; 27(2): 114–122.

- 26. Booth A, Papaioannou D, Sutton A. Systematic approaches to a successful literature review.1st ed. London, United Kingdom: SAGE, 2012.

- 27. Schlosser RW, Wendt O, Bhavnani S, et al Use of information-seeking strategies for developing systematic reviews and engaging in evidence-based practice: the application of traditional and comprehensive pearl growing. A review. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2006; 41(5): 567–582.

- 28. Abdul-Razzak A, You J, Sherifali D, et al. ‘Conditional candour’ and ‘knowing me’: an interpretive description study on patient preferences for physician behaviours during end-of-life communication. BMJ Open 2014; 4(10): e005653.

- 29. Almack K, Cox K, Moghaddam N, et al. After you: conversations between patients and healthcare professionals in planning for end of life care. BMC Palliative Care 2012; 11: 10.

- 30. Burge AT. Advance care planning education in pulmonary rehabilitation: a qualitative study exploring participant perspectives. Palliat Med 2014; 28: 1069–1070.

- 31. MacPherson A, Walshe C, O’Donnell V, et al. The views of patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on advance care planning: a qualitative study. Palliat Med 2013; 27: 265–272.

- 32. Horne G, Seymour J, Shepherd K. Advance care planning for patients with inoperable lung cancer. Int J Palliat Nurs 2006; 12(4): 172–178.

- 33. Singer PA, Martin DK, Lavery JV, et al. Reconceptualizing advance care planning from the patient’s perspective. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158: 879–884.

- 34. Martin DK, Thiel EC, Singer PA. A new model of advance care planning: observations from people with HIV. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159: 86–92.

- 35. Chambers L, Dodd W, McCulloch R, et al A guide to the development of children’s palliative care services. 3rd ed. ACT; 2009. Report No.: ISBN 1 898 447 09 8. Bristol, 2009.

- 36.

- 37.

- 38.

- 39. Noyes J, Booth A, Flemming K, et al. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group Guidance paper 2: methods for assessing methodological limitations, data extraction and synthesis, and confidence in synthesized qualitative findings. J Clin Epidemiol. Epub ahead of print 2 January 2018. DOI: .

- 40. Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, et al. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res 2002; 12(9): 1284–1299.

- 41. Andreassen P, Neergaard MA, Brogaard T, et al. The diverse impact of advance care planning: a long-term follow-up study on patients’ and relatives’ experiences. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015.

- 42. Bakitas M, Dionne-Odom JN, Jackson L, et al. ‘There were more decisions and more options than just yes or no’: evaluating a decision aid for advanced cancer patients and their family caregivers. Palliat Support Care 2016; 12: 1–13.

- 43. Barnes KA, Barlow CA, Harrington J, et al. Advance care planning discussions in advanced cancer: analysis of dialogues between patients and care planning mediators. Palliat Support Care 2011; 9: 73–79.

- 44. Brown M, Brooksbank MA, Burgess TA, et al. The experience of patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and advance care-planning: a South Australian perspective. J Law Med 2012; 20(2): 400–409.

- 45. Burchardi N, Rauprich O, Hecht M, et al. Discussing living wills. A qualitative study of a German sample of neurologists and ALS patients. J Neurol Sci 2005; 237(1–2): 67–74.

- 46. Chen H, Habermann B. Ready or not: planning for health declines in couples with advanced multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs 2013; 45(1): 38–43.

- 47. Epstein AS, Shuk E, O’Reilly EM, et al. ‘We have to discuss it’: cancer patients’ advance care planning impressions following educational information about cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Psychooncology 2015; 24(12): 1767–1773.

- 48. Metzger M, Song MK, Devane-Johnson S. LVAD patients’ and surrogates’ perspectives on SPIRIT-HF: an advance care planning discussion. Heart Lung 2016; 45(4): 305–310.

- 49. Robinson CA. Advance care planning: re-visioning our ethical approach. Can J Nurs Res 2011; 43(2): 18–37.

- 50. Sanders C, Rogers A, Gately C, et al. Planning for end of life care within lay-led chronic illness self-management training: the significance of ‘death awareness’ and biographical context in participant accounts. Soc Sci Med 2008; 66(4): 982–993.

- 51. Simon J, Murray A, Raffin S. Facilitated advance care planning: what is the patient experience? J Palliat Care 2008; 24(4): 256–264.

- 52. Simpson CA. An opportunity to care? Preliminary insights from a qualitative study on advance care planning in advanced COPD. Prog Palliate Care 2011; 9(5): 243.

- 53. Michael N, O’Callaghan C, Baird A, et al. A mixed method feasibility study of a patient- and family-centred advance care planning intervention for cancer patients. BMC Palliat Care 2015; 14: 27.

- 54. Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol 2006; 6: 35.

- 55. Dixon-Woods M, Sutton A, Shaw R, et al. Appraising qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: a quantitative and qualitative comparison of three methods. J Health Serv Res Policy 2007; 12(1): 42–47.

- 56. Folkman S. Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Soc Sci Med 1997; 45(8): 1207–1221.

- 57. Folkman S, Lazarus RS. If it changes it must be a process: study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. J Pers Soc Psychol 1985; 48(1): 150–170.

- 58. Park CL, Folkman S. Meaning in the context of stress and coping. Rev Gen Psychol 1997; 1(2): 115–144.

- 59. Copp G, Field D. Open awareness and dying: the use of denial and acceptance as coping strategies by hospice patients 2002; 7(2): 118–127.

- 60. Morse JM, Penrod J. Linking concepts of enduring, uncertainty, suffering, and hope. Image J Nurs Sch 1999; 31(2): 145–150.

- 61. Stroebe M, Schut H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: rationale and description. Death Stud 1999; 23(3): 197–224.

- 62. Parry R, Land V, Seymour J. How to communicate with patients about future illness progression and end of life: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2014; 4(4): 331–341.

- 63. Pollock K, Wilson E. Care and communication between health professionals and patients affected by severe or chronic illness in community care settings: a qualitative study of care at the end of life. Health Serv Deliv Res 2015; 3: 31.