Introduction

As a profession, nursing has a long history of engaging in advocacy to strengthen and advance the profession, patient care and outcomes, health systems, and public policy. Nursing organizations in particular, continue to serve as critical platforms for policy advocacy—the practice of engaging in political processes to initiate, enact, and enforce structural and policy changes to benefit populations (; ; ). While a plethora of extant literature focuses on advocacy within nursing, attention is largely placed on examining strategies to strengthen individual nurses’ advocacy skills at the patient level, with limited attention to advocacy at the policy level (; ; Reutter & Kushner, 2010; ). Further, despite recognizing policy advocacy as a fundamental component in meeting the profession's social mandate (; ; ), policy advocacy enacted by nursing organizations has been subject to less critical examination. This is an important area of inquiry, as advocacy groups are considered one of the most powerful forces in shaping policy agendas, processes, and outcomes (; ).

To strengthen this function of nursing organizations, examining their policy spheres of influence and impact, decision-making processes, and advocacy approaches can be particularly meaningful. While much can be learned from the policy advocacy work of organizations in other disciplines, advocacy organizations are not equal in their ability to influence public policy; some have greater political clout than others (). The nursing profession's experience in policy advocacy is likely unique given various historical, social, and political factors (e.g., nursing as a gendered profession, the dominance of medicine, society's perceptions of nurses and nursing); and as a result, we chose to situate the review within the nursing context. Although some literature on this topic exists, no comprehensive review has been undertaken to examine the nature, extent, and range of scholarly work focused on nursing organizations and policy advocacy. To our knowledge, two synthesis papers related to this topic exist: conducted a scoping review to examine the factors that influence nursing organizations’ priority setting when undertaking policy advocacy, and conducted an integrative review to examine the differences between regulatory bodies, professional associations, and trade unions. Although these reviews provide a useful overview of specific issues related to nursing organizations’ policy advocacy work, without a comprehensive understanding of the scope of literature that exists, identifying knowledge gaps and areas for further research remains difficult.

The purpose of this review was to fill this knowledge gap by assessing the nature, extent, and range of scholarly work focused on examining policy advocacy undertaken by nursing organizations. Specific objectives included mapping the available body of literature in relation to purpose, time, location, and source; identifying the volume of scholarly work; identifying the ways in which policy advocacy by nursing organizations has been studied; identifying gaps within the literature; and informing the development of additional research questions.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review based on framework with updated guidance by and . Given the exploratory and descriptive nature of the research question, we identified that a scoping review would be the most appropriate knowledge synthesis method.

Research Question

The research question that guided the scoping review was: what is the nature, extent, and range of scholarly work focused on examining nursing organizations’ advocacy to influence change at the policy level? suggest that combining broad questions with a clearly articulated scope of inquiry and defining concepts within the question can be useful to establish an effective search strategy. As a result, we understood policy to be “a statement of direction resulting from a decision-making process that applies reason, evidence, and values in public or private settings” (, p. 88). This included organizational, nursing, health, and public policy at the local (e.g., state or provincial), national, and global levels. Advocacy referred to “the act of supporting or recommending a cause or course of action, undertaken on behalf of persons or issues” (). Nursing organizations referred to regulatory bodies, professional associations, nursing labor unions, specialty nursing practice groups, and nursing student groups at the local, national, and international level.

Search Strategy

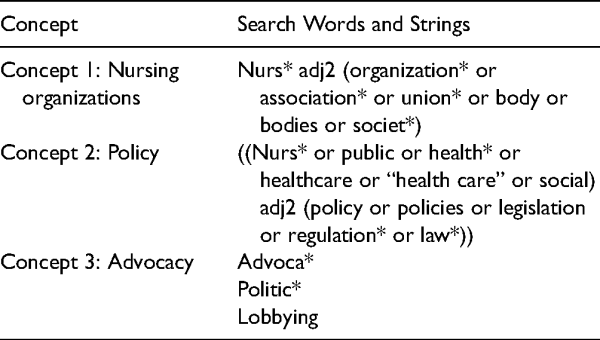

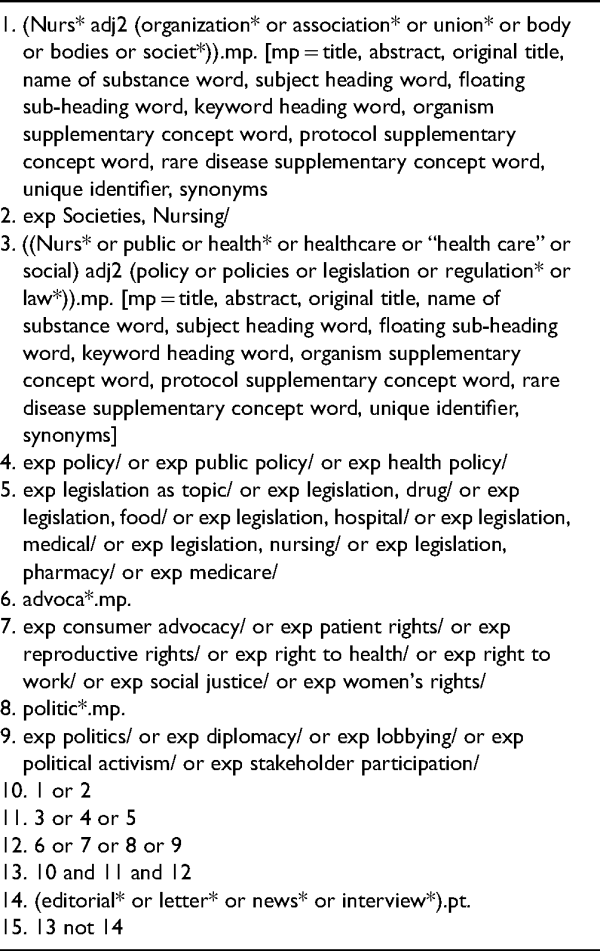

A search was conducted in July 2020 with the assistance of a professional librarian. We searched six databases, including CINAHL, Medline, Embase, Scopus, HealthSTAR, and ProQuest, given the broad range of literature focused on the review topic as indicated in an initial cursory search. The basic structure of the search was organized under three concepts derived from the research question including nursing organizations, advocacy, and policy. Based on these concepts, search terms and search strings were developed (Table 1). Subject headings were used and “exploded” when possible to increase the number of relevant papers (Table 2).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The criteria were purposely broad to ensure all relevant scholarly work was captured to meet the objectives of the review. As suggested by , scoping reviews can include both research and non-research sources. We defined scholarly work broadly to include any research or non-research peer reviewed work focused on both nursing organizations and policy advocacy work. Including various types of peer-reviewed work allowed us to fully examine the nature, extent, and range of literature focused on this topic. For the purposes of this review, dissertations and theses were included given their scholarly merit, despite not being commonly accepted as peer reviewed. We understood research papers to be those that investigated a research question focused on policy advocacy and nursing organizations with methods of data collection (primary or secondary), analysis, and interpretation using a methodological approach (). This included papers of all study designs and methods, as well as dissertations and theses. We understood non-research papers to be those that investigated or discussed a topic, issue, or question related to policy advocacy and nursing organizations without the use of specific methods or methodological approaches. Editorials, commentaries, letters, interviews, and news articles were excluded given the likelihood of limited in-depth exploration and investigation into the topic. Limitations were not placed on publication year or location to meet our objective of mapping the literature in relation to time and location.

Data Management and Article Selection

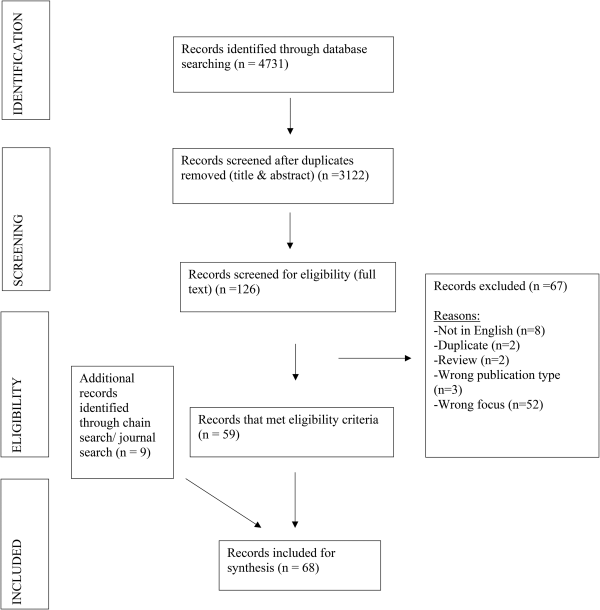

Papers retrieved from the database search were imported into , a web-based software used to store, manage, and screen articles for systematic reviews. Two reviewers (PC and TP) participated in all phases of screening and selection. We piloted the inclusion and exclusion criteria using a sample of 100 papers. We resolved conflicts through consensus and further refined the criteria for clarity. Specifically, we clarified the concept of advocacy at the policy level after the pilot given the heterogeneity of papers and the many forms in which it can be taken up. We also further specified what constituted non-research after gaining a sense of the type of papers retrieved for screening. Reviewers independently screened the papers in both the abstract and title, and full-text screening phases. Additional hand searched articles were retrieved through chain searching, and consensus meetings were held to resolve any conflicts (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram template.

Data Extraction

We used a descriptive-analytical narrative method to chart the data. Two separate data extraction forms—one for research and one for non-research papers were developed using Excel spreadsheets. Fields within the extraction forms were based on the objectives of the research question. Common data extracted from both research and non-research papers included the authors, publication year, organizations’ country of origin, jurisdiction of nursing organization discussed (i.e., global, national, provincial/state level), and aims and purpose. While some features were common to both data extraction forms, there were also some differences. Specifically, the extraction form for research papers included additional fields to capture the methods/designs of studies, theoretical or conceptual frameworks, and key findings; while the extraction form for non-research papers included a field to capture key concepts. We piloted the forms using 10% of the included full-text papers, and discrepancies were resolved through consensus. After the pilot, the first author completed the categorization and data extraction for all full-text articles. Papers were first sorted as research versus non-research. Research papers were then further sorted based on their method/design while non-research papers were sorted into further groupings developed by the author. Where ambiguity was noted during this process, the first author consulted additional reviewers.

Data Analysis

Common descriptive data were summarized and analyzed using descriptive statistics. We extracted text related to the aims and purpose of each paper, key findings, and key concepts, and collated and imported the text into —a qualitative analysis software to assist with data analysis. We used conventional content analysis to analyze extracted text, which is typically employed when existing theory of a phenomenon is limited (). We engaged in basic coding of extracted data as suggested by and developed several categories and sub-categories through an inductive and iterative process ().

Findings

Characteristics of Included Papers

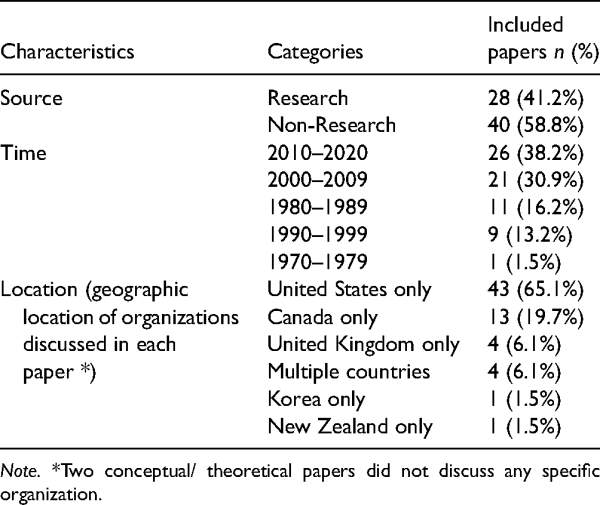

In total, we included 68 papers in the review. We identified 40 (58.8%) as non-research, 28 (41.2%) as research. The literature has been increasing throughout the decades; most papers were published between 2010 and 2020 (n = 26, 38.2%), followed by 2000 and 2009 (n = 21, 30.9%), and 1980 and 1989 (n = 11, 16.2%), respectively. All papers (n = 66, 97%) except two theoretical and conceptual papers discussed a specific nursing organization, with the majority originating from the United States (n = 43, 65.1%) followed by Canada (n = 13, 19.7%) and the United Kingdom (n = 4, 6.1%). Four papers (6.1%) discussed organizations from multiple countries (Table 3).

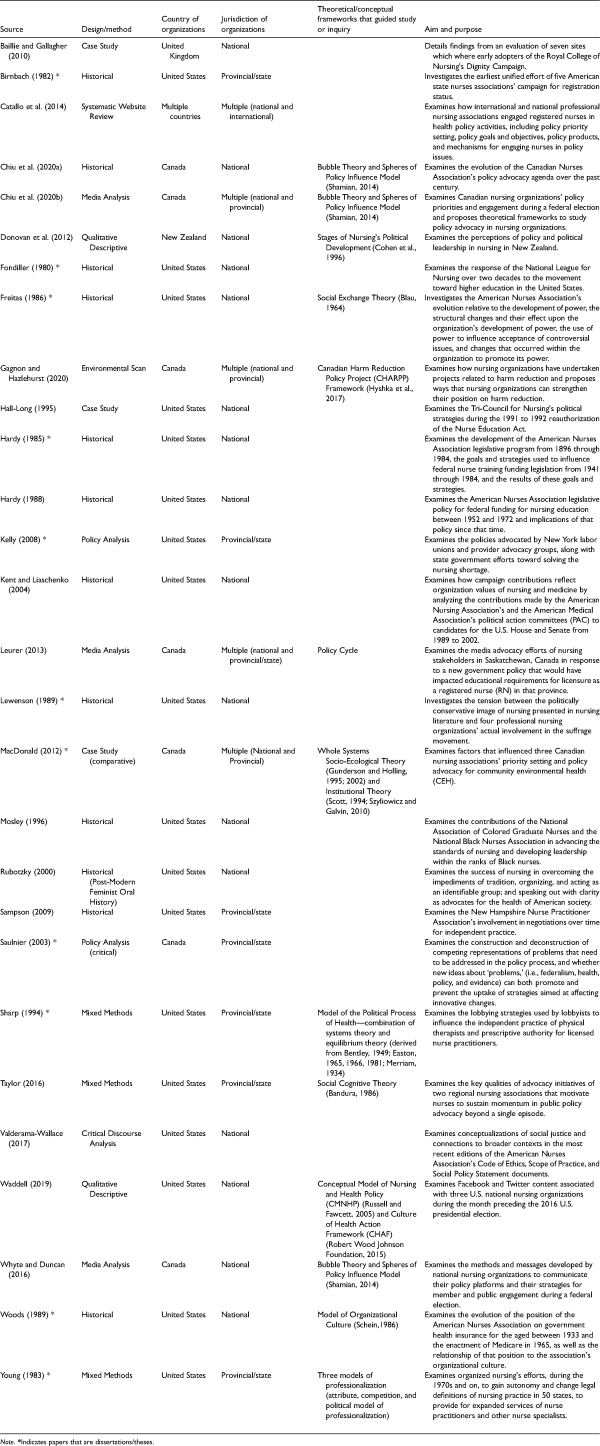

Research Papers

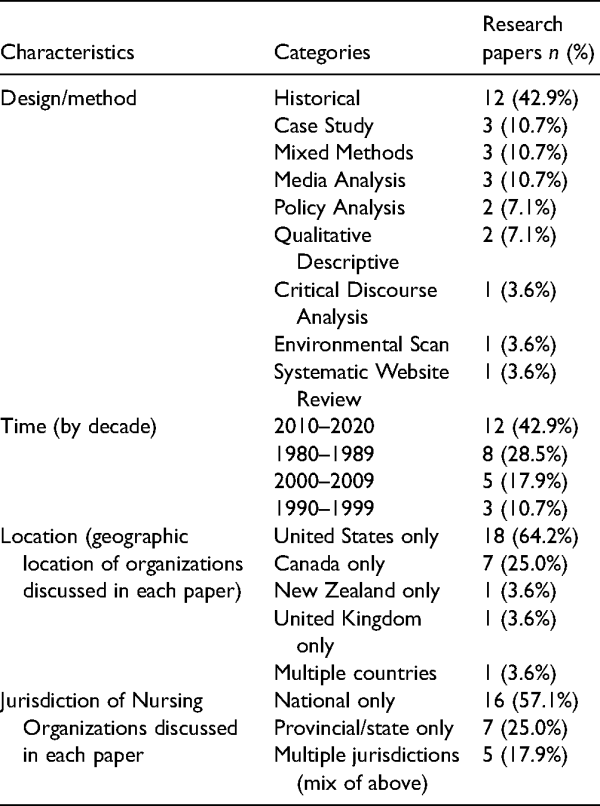

A large portion of research papers employed historical methods (n = 12, 42.9%). Others included case studies (n = 3, 10.7%), mixed methods (n = 3, 10.7%), media analysis (n = 3, 10.7%) policy analyses (n = 2, 7.1%), qualitative descriptive studies (n = 2, 7.1%), critical discourse analysis (n = 1, 3.6%), environmental scan method (n = 1, 3.6%), and systematic website review method (n = 1, 3.6%). Out of the 28 research papers, 11 (39.3%) were dissertations and theses. Most research papers were published between 2010 and 2020 (n = 12, 42.9%) followed by 1980 and 1989 (n = 8, 28.5%), 2000 and 2009 (n = 5, 17.9%), and 1990 and 1999 (n = 3, 10.7%). Papers largely focused their inquiry on nursing organizations located in the United States (n = 18, 64.2%) and Canada (n = 7, 25.0%). Sixteen (57.1%) research papers focused on organizations at the national level, seven (25.0%) discussed organizations at the provincial or state level, and five (17.9%) discussed multiple organizations in different jurisdictions. Theories and conceptual frameworks used to guide research papers varied; however, the majority were related to policy process and development, policy and advocacy knowledge and engagement in nursing, and organizational systems (Tables 4 and 5).

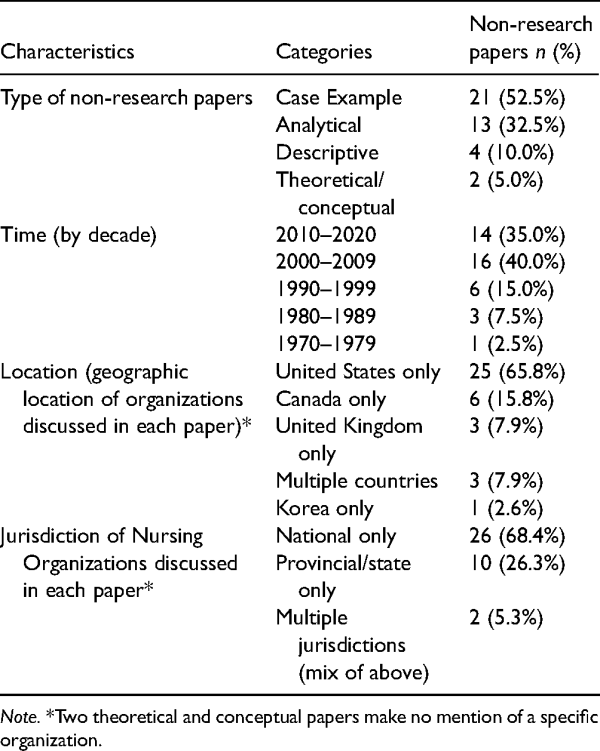

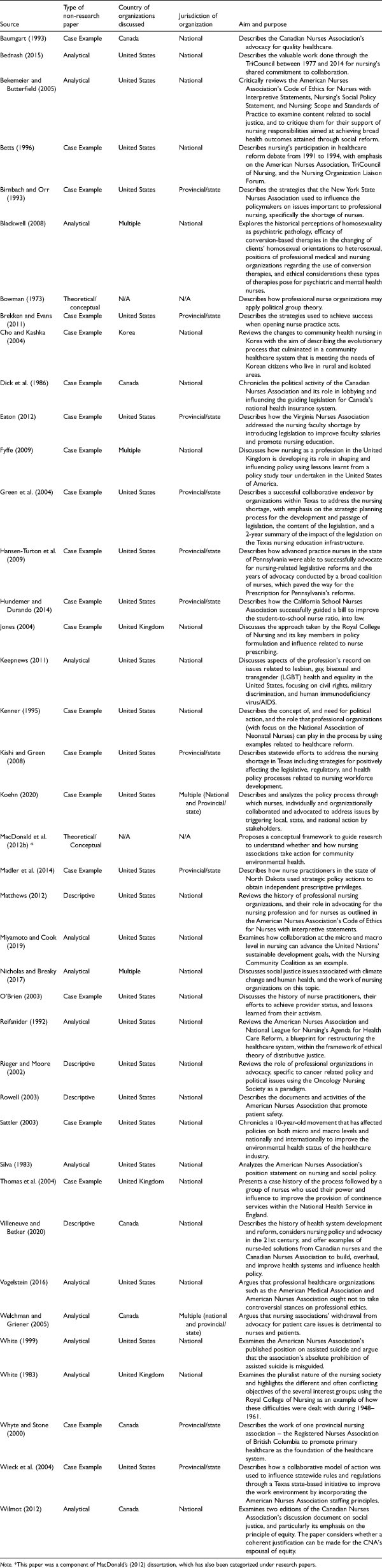

Non-Research Papers

We sorted non-research papers into four key groups. These groups were developed and defined iteratively based on our interpretation of the nature of papers during full-text screening. The four groups developed included (a) analytical papers—those that examined the policy advocacy work of an organization with a presented argument or claim; (b) descriptive papers—those that solely described or summarized the policy advocacy work of an organization with little to no analysis; (c) theoretical and conceptual papers—those that focused on concepts, theories, models, or frameworks used to study nursing organizations, policy, or advocacy; and (d) case examples—those that involved a detailed example or account of advocacy undertaken for a particular policy issue, topic, or event by nursing organizations, without adhering to the methodological principles of an empirical case study approach ().

We sorted over half of the non-research papers as case examples (n = 21, 52.5%), followed by analytical papers (n = 13, 32.5%), descriptive papers (n = 4, 10.0%), and theoretical or conceptual papers (n = 2, 5.0%). The majority were published in the first two decades of the 2000s (n = 30, 75.0%), while the oldest paper was published in the 1970s. Similar to the research papers, the majority discussed nursing organizations located in the United States (n = 25, 65.8%) followed by Canada (n = 6, 15.8%) (Tables 6 and 7).

Key Content of Included Papers

Five key categories were developed to illustrate the nature of scholarly work including (a) the role and purpose of nursing organizations in policy advocacy, (b) the identity of nursing organizations, (c) the development and process of nursing organizations’ policy advocacy initiatives (subcategories: factors influencing policy advocacy initiatives and strategies and tactics), (d) the policy advocacy products of nursing organizations (subcategories: policy positions, and foundational documents and social justice), and (e) the impact and evaluation of nursing organizations’ policy advocacy work.

The Role and Purpose of Nursing Organizations in Policy Advocacy

Seven papers were focused on the role and purpose of nursing organizations within the context of policy advocacy. Some discussed the role of professional nursing organizations in shaping and influencing health and social care policy more broadly (; ; ), while others focused on the role of nursing organizations in advancing a specific policy area such as cancer care () and patient safety (). Two papers took a more critical approach: examined whether professional healthcare associations should take controversial stances on matters related to professional ethics, and the implications of such stances on individual members’ views and positions; while problematized nursing organizations’ withdrawal from advocacy for patient care issues.

The Identity of Nursing Organizations

Five papers were focused on specific characteristics of organizations in relation to their development and identity. discussed the application of political group theory to professional nurse organizations and the characteristics that qualify and make nursing organizations successful as political interest and pressure groups. investigated the tension between nursing's politically conservative image as described in the literature and the progressive positions of four American professional nursing associations during the suffrage movement. The other three papers were focused on discussing the American Nurses Association's development and promotion of power (), organizational culture and relationship with evolving policy positions (), and political preference and values based on donations to political parties ().

The Development and Process of Nursing Organizations’ Policy Advocacy Initiatives

Thirty-seven papers were focused on the development, process, or evolution of an organization's policy advocacy work. Most papers focused on organizations’ advocacy efforts related to a specific policy issue or topic including: nurse training and education (; ; ; ; ), advanced practice or nurse practitioner practice (; ; ; ; ; ; ); nursing shortages, salaries, and staffing issues (; ; ; ; ; ), healthcare reform (), women’s suffrage (), registration status (), nursing legislation (; ), insurance for the aged and enactment of Medicare (), community health (), primary healthcare (), continence services (), cancer care (), environmental health (, ), lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender health and equality (), and key legislation such as the Canadian Health Act (). Of the 37 papers, six were focused on examining nursing organizations’ policy advocacy agenda in a more evolutionary and holistic manner and described their engagement in multiple policy issues over an extended period of time (; ; ; ; ; ).

Factors Influencing Policy Advocacy Initiatives

Twenty-five papers included some discussion on factors that influence organizations’ policy advocacy work. Common internal factors were related to internal expertise, resources and infrastructure (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ), organizational structures, governance, and leadership (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ), and membership size, engagement, and factions (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ). Common external factors were related to relationships and coalitions (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ), political environments (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ), social changes and trends (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ), and healthcare legislation and trends (; ; ; ; ).

Strategies and Tactics

Thirty-seven papers included some discussion on strategies and tactics related to policy advocacy within the organizational context. Some papers were focused on discussing strategies more broadly while others focused on the strategies used by specific organizations. Commonly identified strategies included interorganizational collaboration and coalitions (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ), meeting with policymakers and government (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ), using media and campaigns to garner public support (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ), membership engagement (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ), strategic planning and seeking experts (; ; ; ; ; ; , ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ), and providing testimony and writing letters or briefs to decision makers (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ).

The Policy Advocacy Products of Nursing Organizations

Twenty papers were focused on analyzing or critiquing the policy advocacy products (e.g., position statements, policy briefs, public statements, and discussion papers) of nursing organizations. We further categorized these papers into two sub-categories—those that focused on analyzing or critiquing organizations’ policy positions, and those that focused on organizations’ foundational documents related to social justice.

Policy Positions

Of those 20 papers, 12 were focused on analyzing or critiquing the policy positions of nursing organizations. These papers were focused on examining how organizations constructed their positions in comparison to others (; ; ), the evolution of policy positions overtime (; ; ; ), and the breadth and depth of policy positions in relation to specific topics such as spheres of influence (), harm reduction (), and climate change (). Two papers were focused on critiquing organizations’ positions on matters that were more controversial such as assisted suicide () and conversion therapy ().

Foundational Documents and Social Justice

Eight papers were focused on the foundational policy documents developed by nursing organizations. , , and examined the American Nurses Association's foundational documents (e.g., Code of Ethics, Social Policy Statement) and its utility in providing a framework for nursing's commitment to society and engagement in professional advocacy. critiqued the American Nurses Association and Canadian Nurses Association's Code of Ethics and argued that the over-reliance on individual nurse responsibility has blinded nursing associations from their responsibility in engaging in advocacy related to patient care issues. The other four papers involved a critique of nursing organizations’ documents in relation to the concept of social justice (; ; ; ).

Policy Advocacy Impact and Evaluation

Thirty papers included some discussion on impact, however, only one paper was a formal evaluation of a nursing organization's policy advocacy campaign (). One paper examined the perceptions of policy and political leadership of nursing organizations in New Zealand (). The other 28 papers included mention of organizations’ policy advocacy impact on specific issues (, ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; , ).

Discussion

This review provides an overview of the current state of scholarly work focused on examining the policy advocacy undertaken by nursing organizations. To our knowledge, this is the first scoping review to examine the nature, extent, and range of scholarly work focused on this topic. The broad inclusion criteria enabled the review and analysis of both research and non-research papers, which provided a comprehensive overview of the available literature. The following discussion summarizes the knowledge gaps that have been identified and proposes additional research topics and questions to advance this program of research.

The findings indicate that while the amount of literature has been increasing throughout the decades, policy advocacy within the context of nursing organizations has not been subject to much empirical investigation. Much of the extant literature focuses on national nursing organizations as opposed to those located at the provincial or state level. While we made efforts to categorize the nursing organizations discussed in papers according to their functions based on three common organizational types (regulatory colleges—for public protection; labor unions—for advancing the socioeconomic welfare of nurses; and professional associations—for advancing the profession and influencing public policy) (), the evolving identities, definitions, and functions of organizations created challenges. As a result, accurate categorization was not possible as the clear delineations and conceptualizations between professional associations, unions, and regulatory bodies that exist today were not the case when many of the included papers were written.

The majority of included papers were non-research accounts and descriptions of organizations’ policy advocacy work. Where empirical work exists, there are minimal studies within the contemporary context. While some included in the review were unclear in their reporting of research methodologies and methods, it is clear that many of the studies used a historical method, and other studies were largely qualitative and retrospective. Although these approaches are often employed to describe and understand past events, successes and challenges, and the unique processes involved in policy advocacy; studies focused on policy implementation, outcomes, and evaluation using quantitative and mixed-methods approaches are also required to provide direction for how nursing organizations’ policy advocacy work can be better situated, conducted, and implemented.

Research Gaps and Further Areas of Inquiry

While the findings provide us with some understanding about the policy advocacy work of nursing organizations and how it has been studied; the existing body of work does not provide us with sufficient knowledge to understand how this work can be strengthened to achieve optimal outcomes. We acknowledge that the extant literature focused on policy advocacy of organizations within other disciplines or sectors may inform the work of nursing organizations; however, the unique historical, social, and political contexts in which nursing is situated across jurisdictions require more focused inquiry. Specifically, while generalizations from existing literature can be useful, nursing knowledge requires careful attention to contexts. The areas of inquiry identified in this section provide readers, specifically nurse researchers and policy advocacy practitioners, with considerations for how nursing organizations’ role, influence, and impact can be further investigated to strengthen this critical function.

Linking Decision-Making Processes with Theories of Policy Process and Change

Findings from the review suggest that nursing organizations are engaged in a variety of policy issues and employ several advocacy strategies and tactics to influence and shape policy. Although many papers were focused on discussing the internal and external factors that influenced the development or process of an advocacy initiative, there was little emphasis on the process of decision making that influenced their priority setting and advocacy strategies—two commonly investigated areas within policy studies. Several theories of policy process and change exist, and many influence the approaches taken by policy advocacy groups (). By examining the decision-making processes of individuals leading the policy advocacy work of nursing organizations and considering them within the context of promising practices and existing theories, the work of nursing organizations can be better evaluated to identify practices that should be leveraged and areas that require improvement.

The Impact of Organizational Factors on Policy Advocacy Process and Outcomes

Despite discussions around the influence of organizational culture and identity on policy advocacy approaches within the included papers, the relationships between internal processes, structures, leadership, and climate on the level of visibility, effectiveness, and influence of organizations has not been widely studied within the nursing context. Institutional theory () can be particularly useful in examining how rules, norms, and culture influence organizations’ decision making about their policy advocacy work; and how they positively or negatively impact their outcomes. Cross case comparisons would be meaningful to identify whether trends or patterns exist between organizations’ internal cultures, structures, and processes, and their level of effectiveness in policy advocacy. This is a particularly important area to consider, as it has the potential to inform individuals working within nursing organizations about the internal factors that support or hinder effective policy advocacy processes and outcomes.

From a governance perspective, further investigation into the nuances between joint versus single mandated organizations, stand-alone organizations versus nationally federated models, and unions versus professional associations is needed. While many nursing organizations discussed within the included papers have evolved over time, scholars have focused very little attention on examining the impact of changing governance structures on organizations’ policy advocacy processes, practices, and outcomes. This could involve examining the differences and similarities in policy advocacy engagement, whether the public and decision makers view them differently, and the implications on the success and effectiveness of policy influence. As illustrated by , differences in activities, principal policy focus, political partisanship, source of power, and methods of advocacy have been noted within the literature between regulators, associations, unions. Consequently, by further examining these areas of inquiry, nursing organizations may be better informed as to how they might choose to govern and organize to maximize policy influence and impact.

The Use of External Perspectives to Inform Policy Advocacy Approaches

Another observation noted from the findings is the lack of literature focused on nursing organizations and policy advocacy from an external perspective—that of elected officials or bureaucrats within governments, leaders within other advocacy groups, and members of such organizations. While understanding the internal processes of policy advocacy within organizations is important for identifying ways to improve this work, it is not the only perspective that can inform change. The success of policy advocacy is influenced by several external factors. As suggested in the findings, many nursing organizations seek to influence the decision-making processes of key decision makers. As a result, understanding how they are perceived in the eyes of external stakeholders can inform the advocacy strategies that are taken up. Future research questions may include the following: How do individuals within governments or key decision makers perceive different nursing organizations? What do they make of the policy advocacy work of such organizations and what approaches are they most likely to respond to? How do these perceptions differ from non-nursing organizations?

Advocacy and Policy Change Evaluation

While some of the papers made mention of the impact of organizations’ policy advocacy initiatives (; , ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; , ), greater empirical research is needed to evaluate and examine the relationship between specific advocacy strategies and outcomes such as changes in public awareness and perception, legislation, policy, and practice. Advocacy and policy change evaluation is an important area of inquiry as advocacy organizations are increasingly expected to demonstrate the value of their work to their membership, stakeholders, and funders (). Although it may be difficult to identify direct causal relationships given the complexity of the policy making process, evaluating the impact and outcomes of organizations’ advocacy work is ultimately required to identify the ways in which organizations can achieve greater influence and impact.

A Critical Lens to Challenge the Status Quo

As indicated in the findings, while some critical analysis of nursing organizations’ engagement on social justice issues exist, scholarship focused on examining nursing organizations’ involvement in significant social movement is limited. Given the civil rights movements within the last few years (), greater critical analysis is warranted to examine whether the actions of nursing organizations that promote an advocacy role are adequate and effective in addressing the social injustices confronting our time to ensure that these institutions uphold their ethical, moral, and professional obligations. A critical lens may be useful for examining the following questions: How are nursing organizations framing these complex issues? What rhetoric are they engaging in or promoting? How do these issue frames shape nursing organizations’ policy advocacy actions? Is the policy advocacy work of nursing organizations adequate in informing changes at the individual, organizational, and systems levels? These questions provide both researchers and policy advocacy leaders with an opportunity to critically reflect on the unique role and position of nursing organizations in addressing these pressing and complex societal issues.

Approaches to Inquiry

The areas of inquiry identified above can be investigated using a variety of research methods and theoretical frameworks developed in the fields of nursing, social science, policy studies, and organizational studies. Future research related to policy advocacy undertaken by nursing organizations can be examined by focusing on different units of study. For example, researchers may choose to examine organizations’ policy advocacy within the context of a single or on-going event (e.g., a political election, coronavirus pandemic), a process (e.g., decision-making process related to priority setting and advocacy strategies), a relationship (e.g., coalitions within and beyond nursing), or a specific project or policy issue (e.g., mental health, primary healthcare, human resources of health, etc.).

While much of the extant research and non-research literature is focused on examining the policy advocacy work of a single organization, greater attention should also be placed on studying and comparing organizations across jurisdictions at the national and global level. Although some papers did compare nursing organizations with those of other disciplines, most focused internally within the profession. Consequently, there may be much to be gained from future investigations that explicitly compare nursing organizations’ policy advocacy approaches against those of other disciplines. This would not only enhance our understanding of the similarities that exist irrespective of different contexts, but the aspects of policy advocacy that are more sensitive to change based on the various professional, social, political, and economic contexts.

Limitations

Only papers published in English were included given the lack of translation services available. Further, given the unclear reporting of methodologies in some research papers, and the sorting of non-research papers into categories developed by the author, a level of interpretation and judgement was required. Where there was a level of ambiguity, additional reviewers based on expertise were consulted to reach consensus. However, from the body of literature available, there is sufficient breadth and scope to understand the type of questions that nurses have been asking about the advocacy capacity of their organizations and the answers they are providing.

Conclusion

Policy advocacy is often accepted without question as a key function of many nursing organizations. As a result, it has not been subject to much critical examination or empirical investigation. This review has provided an overview of the nature, extent, and range of scholarly work focused on examining policy advocacy undertaken by nursing organizations. The findings lay the groundwork for future areas of inquiry and suggest that a more focused and critically reflective body of knowledge is required to help challenge current approaches, identify areas for improvement, and offer new insights into how these institutions can best meet the needs of nurses, the public, and health systems. To continue to strengthen the policy influence of nursing globally for the betterment of our societies and healthcare systems, our focus must extend beyond the advocacy undertaken by individual nurses to ensure we effectively mobilize the capacity of nursing organizations to have optimal impact on policy, practice, and society.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Tatiana Penconek during all phases of the screening process.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD Patrick Chiu https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9758-6666

Supplemental Material Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Baillie L., Gallagher A. (2010). Evaluation of the royal college of nursing’s ‘dignity: At the heart of everything we do’ campaign: Exploring challenges and enablers. Journal of Research in Nursing, 15(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987109352930

- Bandura A. (1989). Social cognitive theory. In R. Vasta (Ed.). Annals of child development (Vol.6, pp. 1-60). JAI Press.

- Baumgart A. J. (1993). Quality through health policy: The Canadian example. International Nursing Review, 40(6), 167–170.

- Blau P.M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. John Wiley & Sons.

- Bednash G. P. (2015). The tricouncil for nursing: An interorganizational collaboration for advancing the profession. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 39(3), 218–228. https://doi.org/10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000105

- Bekemeier B., Butterfield P. (2005). Unreconciled inconsistencies: A critical review of the concept of social justice in 3 national nursing documents. Advances in Nursing Science, 28(2), 152–162. https://doi.org/10.1097/00012272-200504000-00007

- Bentley A. F. (1949). The process of government: A study of social pressures. Principal Press.

- Benton D. C., Thomas K., Damgaard G., Masek S. M., Brekken S. A. (2017). Exploring the differences between regulatory bodies, professional associations, and trade unions: An integrative review. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 8(3), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2155-8256(17)30154-0

- Betts V. T. (1996). Nursing’s agenda for health care reform: Policy, politics and power through professional leadership. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 20(3), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006216-199602030-00003

- Birnbach N. S. (1982). The genesis of the nurse registration movement in the United States: 1893-1903 (Publication No.8313393). Doctoral dissertation, Columbia University Teachers College. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Birnbach N., Orr M. L. (1993). An association’s campaign to influence policy. International Nursing Review, 40(6), 175–178.

- Blackwell C. W. (2008). Nursing implications in the application of conversion therapies on gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender clients. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 29(6), 651–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840802048915

- Bowman R. A. (1973). The nursing organization as a political pressure group. Nursing Forum, 12(1), 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6198.1973.tb00526.x

- Brekken S. A., Evans S. (2011). Strategies for opening the nurse practice act. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 1(4), 32–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2155-8256(15)30311-2

- Bryant T. (2009). Health policy in Canada (2nd ed.). Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc.

- Canadian Nurses Association. (2017). Code of ethics for registered nurses. Author. https://www.cna-aiic.ca/-/media/cna/page-content/pdf-en/code-of-ethics-2017-edition-secure-interactive.pdf

- Canadian Nurses Association. (2020). Policy and advocacy. Retrieved from https://www.cna-aiic.ca/en/policy-advocacy

- Catallo C., Spalding K., Haghiri-Vijeh R. (2014). Nursing professional organizations: What are they doing to engage nurses in health policy? SAGE Open, 4(4), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014560534

- Cho H. S. M., Kashka M. S. (2004). The evolution of the community health nurse practitioner in Korea. Public Health Nursing, 21(3), 287–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0737-1209.2004.021311.x

- Cohen S. S., Mason D. J., Kovner C, Leavitt J. K., Pulcini J., Sochalski J. (1996) Stages of nursing’s political development: Where we’ve been and where we ought to go. Nursing Outlook, 44(6), 259–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0029-6554(96)80081-9

- Covidence. (2020). [Computer Software]. Retrieved from https://www.covidence.org

- Creswell J.W., & Creswell J.D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. (5th ed). Sage.

- Dick D., Harris B., Lehman A., Savage R. (1986). Getting into the act: A Canadian nurse’s experience. International Nursing Review, 33(6), 165–170.

- Donovan D. J., Diers D., Carryer J. (2012). Perceptions of policy and political leadership in nursing in New Zealand. Nursing Praxis in New Zealand, 28(2), 15–25. https://www.nursingpraxis.org/282-perceptions-of-policy-and-political-leadership-in-nursing-in-new-zealand.html

- Duncan S., Thorne S., Rodney P. (2015). Evolving trends in nurse regulation: What are the policy impacts for nursing’s social mandate? Nursing Inquiry, 22(1), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/nin.12087

- Easton D. (1965). A framework for political analysis. Prentice-Hall.

- Easton D. (1966). Varieties of political policy. Prentice-Hall.

- Easton D. (1981). The political system. The University of Chicago Press.

- Eaton M. K. (2012). Professional advocacy: Linking Virginia’s story to public policy-making theory, learning from the past and applying to our future. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 13(2), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527154412449746

- Ellenbecker C.H., Fawcett J., Jones E.J., Mahoney D., Rowlands B., Waddell A. (2017). A staged approach to educating nurses in health policy. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 18(1), 44–56.

- Fondiller S. H. (1980). The national league for nursing 1952-1972: Responses to the higher education movement (Publication No. 8111538). [Doctoral dissertation, Columbia University Teachers College]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Freitas L. (1986). Evolution of the professional nursing organization: Development of power (Publication No. 8706003). [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Fyffe T. (2009). Nursing shaping and influencing health and social care policy. Journal of Nursing Management, 17(6), 698–706. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00946.x

- Gardner A. L., Brindis C. D. (2017). Advocacy and policy change evaluation: Theory and practice. Stanford University Press.

- Green A., Wieck K. L., Willmann J., Fowler C., Douglas W., Jordan C. (2004). Addressing the texas nursing shortage: A legislative approach to bolstering the nursing education pipeline. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 5(1), 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527154403260139

- Gunderson L., & Holling C. (2002). Panarchy: Understanding transformations in human and natural systems. Island Press.

- Gunderson L., Holling C., & Light S. (1995). Barriers and bridges to the renewal of ecosystems and institutions. Columbia University Press.

- Hall-Long B. (1995). Nursing education at the crossroads: Political passages. Journal of Professional Nursing, 11(3), 139–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/S8755-7223(95)80112-X

- Hansen-Turton T., Ritter A., Valdez B. (2009). Developing alliances: How advanced practice nurses became part of the prescription for Pennsylvania. Policy, Politics & Nursing Practice, 10(1), 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527154408330206

- Hardy M. A. (1985). The American nurses’ association influence on federal funding for nursing education (1941-1984) movement (Publication No. 8727973). [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Iowa]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Hardy M. A. (1988). Political savvy or lost opportunity? Evolution of the American nurses’ association policy for nursing education funding, 1952 to 1972. Journal of Professional Nursing, 4(3), 205–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/S8755-7223(88)80138-8

- Hsieh H., Shannon S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 127 1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Hundemer K., Durando D. (2014). One NASN state affiliate’s perspective of legislative advocacy. NASN School Nurse, 29(1), 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1942602X13492422

- Hyshka E., Anderson-Baron J., Karekezi K., Belle-Isle L., Elliott R., Pauly B., Strike C., Asbridge M., Dell C., McBride K., Hathaway A., Wild T. C. (2017). Harm reduction in name, but not substance: A comparative analysis of current Canadian provincial and territorial policy frameworks. Harm Reduction Journal, 14(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-017-0177-7

- Jones M. (2004). Case report. Nurse prescribing: A case study in policy influence. Journal of Nursing Management, 12(4), 266–272. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2004.00480.x

- Keepnews D. M. (2011). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health issues and nursing: Moving toward an agenda. Advances in Nursing Science, 34(2), 163–170. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANS.0b013e31821cd61c

- Kelly K. (2008). Collective wisdom? An examination of policy positions of several organizations concerning New York’s nursing shortage (Publication No. AAI1452294). [Master’s thesis, State University of New York Empire State College]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Kenner C. (1995). Use of professional associations for political action. The Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing, 9(1), 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005237-199506000-00011

- Kent R. L., Liaschenko J. (2004). Operationalizing professional values through PAC donations. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 5(4), 243–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527154404269100

- Kishi A., Green A. (2008). A statewide strategy for nursing workforce development through partnerships in Texas. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 9(3), 210–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527154408317727

- Koehn K. (2020). Triggers for nursing policy action: Getting to the critical point to solving “ordinary problems” in nursing. Nursing Forum, 55(1), 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12376

- Leurer M. D. (2013). Lessons in media advocacy: A look back at Saskatchewan’s nursing education debate. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 14(2), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527154413493671

- Levac D., Colquhoun H., O’Brien K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Lewenson S. (1989). The relationships among the four professional nursing organizations and woman suffrage: 1893-1920 (Publication No. 9002561). [Doctoral dissertation, Teachers College Columbia University]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- MacDonald J. T. (2012). Priority setting and policy advocacy for community environmental health: A comparative case study of three Canadian nursing associations (Publication No. NR98127). [Doctoral dissertation, University of Ottawa]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Madler B. J., Kalanek C. B., Rising C. (2014). Gaining independent prescriptive practice: One state’s experience in adoption of the APRN consensus model. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 15(3-4), 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527154414562299

- Matthews J. (2012). Role of professional organizations in advocating for the nursing profession. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 1(17). https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol17No01Man03

- Merriam C. E. (1934). Political power. McGraw-Hill.

- Miljan L. (2018). Public policy in Canada: An introduction (7th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Miyamoto S., Cook E. (2019). The procurement of the UN sustainable development goals and the American national policy agenda of nurses. Nursing Outlook, 67(6), 658–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2019.09.004

- Moorley C., Darbyshire P., Serrant L., Mohamed J., Ali P., De Souza R. (2020). Dismantling structural racism: Nursing must not be caught on the wrong side of history. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(10), 2450–2453. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14469

- Mosley M. O. (1996). A new beginning: The story of the national association of colored graduate nurses, 1908-1951 (second in the three-part series despite all odds: A history of the professionalization of black nurses through two professional organizations, 1908–1995). Journal of National Black Nurses’ Association, 8(1), 20–232.

- Nicholas P. K., Breakey S. (2017). Climate change, climate justice, and environmental health: Implications for the nursing profession. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 49(6), 606–616. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12326

- O’Brien J. M. (2003). How nurse practitioners obtained provider status: Lessons for pharmacists. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 60(22), 2301–2307. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajhp/60.22.2301

- Peters M., Marnie C., Tricco A. C., Pollock D., Munn Z., Alexander L., McInerney P., Godfrey C. M., Khalil H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(10), 2119–2126. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-20-00167

- Reifsnider E. (1992). Restructuring the American health care system: An analysis of nursing’s agenda for health reform. Nurse Practitioner, 17(5), 65–675. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006205-199205000-00016

- Reutter L., Duncan S. (2002). Preparing nurses to promote health-enhancing public policies. Policy, Politics & Nursing Practice, 3(4), 294–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/152715402237441

- Reutter L., Kushner K. E.. (2010). Health equity through action on the social determinants of health: Taking up the challenge in nursing. Nursing Inquiry, 17(3), 269–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1800.2010.00500.x

- Rieger P. T., Moore P. (2002). Professional organizations and their role in advocacy. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 18(3), 276–289. https://doi.org/10.1053/sonu.2002.35936

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (2015). From vision to action: Measures to mobilize a culture of health. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

- Rowell P. A. (2003). The professional nursing association’s role in patient safety. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 8(3), 3. https://ojin.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/TableofContents/Volume82003/No3Sept2003/AssociationsRole.html

- Rubotzky A. M. (2000). Nursing participation in health care reform efforts of 1993 to 1994: Advocating for the national community. Advances in Nursing Science, 23(2), 12–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/00012272-200012000-00004

- Russel G., Fawcett J. (2005). The conceptual model for nursing and health policy revisited. Policy, Politics and Nursing Practice, 6(4) 319–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527154405283304

- Sampson D. A. (2009). Alliances of cooperation: Negotiating New Hampshire nurse practitioners’ prescribing practice. Nursing History Review, 17(1), 153–178. https://doi.org/10.1891/1062-8061.17.153

- Sattler B. (2003). The greening of health care: Environmental policy and advocacy in the health care industry. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 4(1), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527154402239449

- Saulnier C. M. (2003). Analyzing public policy as if ideas mattered: Health policy ‘problems,’ gender and restructuring in New Brunswick (Publication No. NQ86362). [Doctoral dissertation, York University]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Schein E.H. (1986) Organizational culture and leadership. Jossey-Bass.

- Scott R. (1994). Institutions and organizations: Toward a theoretical synthesis. In Scott R., Meyer J. (Eds.), Institutional environments and organizations: Structural complexity and individualism (pp. 55–580). Sage Publications.

- Scott W. R. (2013). Institutions and organizations: Ideas, interests and identities (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Shamian J. (2014). Global perspectives on nursing and its contribution to healthcare and health policy: Thoughts on an emerging policy model. Nursing Leadership, 27(4), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.12927/cjnl.2015.24140

- Sharp J. H. (1994). An analysis of lobbying strategies used to influence health policy (Publication No.9429411). [Doctoral dissertation, George Mason University]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Silva M. C. (1983). The American nurses’ association’s position statement on nursing and social policy: Philosophical and ethical dimensions. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 8(2), 147–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.1983.tb00305.x

- Skelton-Green J., Shamian J., Villeneuve M. (2014). Policy: The essential link in successful transformation. In McIntyre M., McDonald C. (Eds.), Realities of Canadian nursing: Professional, practice and power issues (4th ed., pp. 87–113). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Spenceley S.M, Reutter L., Allen M.N. (2006). The road less traveled: Nursing advocacy at the policy level. Policy, Politics & Nursing Practice, 7(3),180–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527154406293683.

- Szyliowicz D., Galvin T. (2010). Applying broader strokes: Extending institutional perspective and agendas for international entrepreneurship research. International Business Review, 19(4), 317–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2010.01.002

- Taylor M. R. S. (2016). Impact of advocacy initiatives on nurses’ motivation to sustain momentum in public policy advocacy. Journal of Professional Nursing, 32(3), 235–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2015.10.010

- Thomas S., Billington A., Getliffe K. (2004). Improving continence services – a case study in policy influence. Journal of Nursing Management, 12(4), 252–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2004.00483.x

- Valderama-Wallace C. P. (2017). Critical discourse analysis of social justice in nursing’s foundational documents. Public Health Nursing, 34(4), 363–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12327

- Villeneuve M., Betker C. (2020). Nurses, nursing associations, and health systems evolution in Canada. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 25(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol25No01Man06

- Vogelstein E. (2016). Professional hubris and its consequences: Why organizations of health-care professions should not adopt ethically controversial positions. Bioethics, 30(4), 234–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12186

- Waddell A. (2019). Nursing organizations’ health policy content on Facebook and Twitter preceding the 2016 United States presidential election. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(1), 119–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13826

- Welchman J., Griener G. G. (2005). Patient advocacy and professional associations: Individual and collective responsibilities. Nursing Ethics, 12(3), 296–304. https://doi.org/10.1191/0969733005ne791oa

- White B. C. (1999). Assisted suicide and nursing: Possibly compatible? Journal of Professional Nursing, 15(3), 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/S8755-7223(99)80036-2

- White R. (1983). Pluralism, professionalism and politics in nursing. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 20(4), 231. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7489(83)90015-9

- Whyte N., Duncan S. (2016). Engaging nursing voice and presence during the Federal Election Campaign 2015. Canadian Journal of Nursing Leadership, 29(4), 19–34. https://doi.org/10.12927/cjnl.2016.24986

- Whyte N., Stone S. (2000). A nursing association’s leadership in primary health care: Policy, projects and partnerships in the 1990s. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 32(1), 57–69.

- Wieck K. L., Oehler T., Green A., Jordan C. (2004). Safe nurse staffing: A win-win collaboration model for influencing health policy. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 5(3), 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527154404266578

- Wilmot S. (2012). Social justice and the Canadian nurses association: Justifying equity. Nursing Philosophy, 13(1), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-769X.2011.00518.x

- Woods C. (1989). Evolution of the American Nurses Association’s Position on Health Insurance for the Aged: 1933-1965 (Publication 9020075). [Dissertation thesis, University of Kansas]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Yin R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Designs and methods. (6th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Young W. B. (1983). Nursing autonomy: The politics of nursing (Publication No. 8320634). [Dissertation thesis, University of Illinois at Chicago]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.